Abstract

Information and communication technologies (ICT) has the ability to create value by enabling other firm capabilities. Based on the ICT-enabled capabilities perspective, this study explores the direct and indirect effects between lower- and higher-order capabilities, such as ICT, knowledge management capability (KM) and product innovation flexibility (PIF), on the performance of Ibero-American small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). This paper uses second-order structural equation models to test the research hypotheses with a sample of 130 Ibero-American SMEs. The results contribute to filling the gap in the SME-focused literature on empirical studies examining ICT-enabled capabilities and firm performance. The results show an enabling effect of ICT on higher-order capabilities, such as KM and PIF, which, by acting as mediating variables, create value and improve performance through innovation in firms.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Now more than ever, small and medium enterprises (SMEs hereinafter) operate in turbulent and dynamic environments characterized by increased competition and changes in the needs and behavior of individuals (van de Vrande et al. 2009; Parida et al. 2016). An example of the above is reflected in the export of manufactured products in Asian countries. For example, China and India enjoy more competitive manufacturing costs and prices and represent a serious competitive threat to SMEs from other countries (Terziovski 2010). In addition to these difficulties, several studies have indicated that SMEs face other difficulties related to acquiring resources and deploying their capabilities, which represent an additional challenge to their ability to compete in current markets (Sok et al. 2016).

Despite their limitations, SMEs have had to adapt and strengthen various capabilities to achieve competitive advantages and improve their performance. In the context of increasing technological evolution, several SMEs have been pushed to develop capabilities to properly manage information and communication technology (ICT hereinafter), thus allowing them to benefit from improved communication with their networks and capture a wealth of useful information. For example, Gaviria-Marin and Cruz-Cázares (2020) point out that SMEs are increasingly using web platforms to acquire various types of knowledge, which has allowed them to improve other skills. In this sense, some recent studies show that the development of these technological capabilities is catalyzing/supporting the development of other more complex capabilities (Soto-Acosta et al. 2018; Cai et al. 2019; Felipe et al. 2020), denoting thereby the integration or complementarity between various resources/capacities of the company. In fact, it is well known that organizational capabilities are integrated or complemented by other capabilities of varying complexity, allowing companies to achieve competitive advantages over the competition and improve performance (Ennen and Richter 2010; Bi et al. 2019).

The resource-based view (RBV hereinafter) literature provides a solid theoretical foundation to explain how firms use, integrate and complement different capabilities for value creation, which has led some researchers to offer a classification of these capabilities (Penrose 1959; Teece and Pisano 1994; Teece et al. 1997). Along these lines, Grant (1996) proposed a hierarchy and identified and classified abilities as lower order and higher order. According to this study, the base of this hierarchy is formed by resources and knowledge at the individual level, and when these capabilities are integrated, they form lower-order capabilities. Combining these capabilities will form higher-order capabilities that ultimately contribute to value creation (Hoopes and Madsen 2008). The literature suggests in this sense that the impact of lower-order capabilities on the performance of firms is indirect and that they need other, more complex capabilities to achieve this effect (Felipe et al. 2020). In this sense, ICT has been widely recognized as a lower-order capability with significant potential to catalyze other, more complex capabilities (Mao and Quan 2015; Felipe et al. 2020). This implies that ICT capabilities can have an important impact on firm performance but only through other higher-order capabilities. Several observational studies have been published showing the catalytic and enabling role of ICT (Sambamurthy et al. 2003; Rai et al. 2006; Bi et al. 2019; Felipe et al. 2020). However, given that organizational capabilities are numerous and diverse, research remains to be done to clarify and improve the understanding of the enabling role of ICT on other higher-order capabilities and its impact on SME performance.

Taking this into account, this research focuses on two higher-order business capabilities, which in the face of market dynamism, may be particularly important: flexibility in product innovation (PIF hereinafter) and knowledge management (KM hereinafter). The first of these, PIF, refers to a firm's strategic ability to produce different combinations of products/services and launch them to the market effectively and efficiently in response to changes in the environment (Liao and Barnes 2015). Some studies propose that ICT capabilities can have a positive impact on the flexibility of new product development (Ganbold et al. 2020). For example, information systems can provide relevant information to firms to implement flexibility in the development of new product/service combinations (Byrd and Turner 2001). When firms have ICT capabilities, they can manage and have relevant market information available for decision making on the various innovation processes. This is key for smaller firms since proper information management helps them to more quickly adapt their products/services, which is a capability that can facilitate customer satisfaction (Kim et al. 2011; Sáenz et al. 2018). This suggests that successful PIF implementation requires the appropriate management of a significant amount of information and knowledge both internally and externally (Bamel and Bamel 2018); hence, a second higher-order capability that is incorporated in this study is KM, whose relationship with ICT capabilities has previously been explored in the literature (Sambamurthy et al. 2003; Tanriverdi 2005). KM is related to a set of processes that generates value for firms from the organization of knowledge such that it is made available when needed (O’Brien and Marakas 2006; Sandhawalia and Dalcher 2011). Higher-order capabilities, such as PIF and KM, are complex strategic capabilities that require superior skills and knowledge in several management areas. However, they can also be catalyzed and enabled by lower-order capabilities, such as ICT capabilities. Therefore, our objective, based on the RBV literature, specifically the ICT-enabled capabilities perspective (Rai et al. 2006), is to propose and analyze a structural model that advances the understanding of the enabling capability of ICT (a lower-order capability) for other higher order capabilities, such as PIF and KM, and to analyze the effect of this on SME performance. For this purpose, we focus on the context of Ibero-American SMEs from Spain, Colombia, and Chile. Although these countries present marked economic/cultural differences, this study allows us to validate a complex theoretical model that has not been tested in the literature to date.

This research makes several contributions. First, we provide and test a new explanatory model of direct and indirect relationships between capabilities of different orders (such as ICT capabilities, PIF, KM) and SME performance. In this sense, this study contributes to the theoretical understanding of the catalytic and enabling effects of ICT on other more complex capabilities, such as PIF and KM, which allows us to reinforce the idea that these capabilities are key in the effect of ICT on the performance of SMEs. This allows us to not only highlight the importance of ICT capabilities in companies that are often characterized by limited resources but also emphasize that the relationship between capabilities of different orders creates a synergy with an important potential to create value in smaller firms. Second, we propose and validate an original structural model with conceptual variables that have not been analyzed jointly in previous studies. To the best of our knowledge, the studies that assume the relationships between ICT, PIF, and KM capability and SME performance are scarce. Those that exist partially address the relationships between the constructs presented in this study. Finally, we believe that our findings are valid and contribute both academically and professionally.

The document is structured as follows. First, a theoretical framework and the formulation of the research hypotheses are presented. Second, the methodology section presents the procedures used for data collection and tests the hypotheses by analyzing second-order structural equations. In the third section, the results are presented and discussed. Finally, the last section presents the main findings, conclusions, and limitations.

2 Background and theoretical framework

The resource-based view (RBV) indicates that firm competitiveness and performance depend on the availability of valuable, rare, inimitable, and irreplaceable resources (Barney 1991). Other researchers point out that organizational performance will be a function of the efficient use of an organization’s resources and the deployment of its capabilities to manage resources, design internal processes, and transform those processes (Barney 1991; Roos et al. 2002; Parida and Örtqvist 2015). From this point of view, to face market dynamism and turbulence, achieve a competitive advantage, and create organizational value, firms must strengthen and reconfigure different types of capabilities (Ennen and Richter 2010). This suggests that organizational capabilities often complement and integrate with each other, making the internal processes of the firm more complex and giving them a connotation of high organizational value (Carmeli and Tishler 2004).

According to Winter (2000), organizational capabilities are "high-level routines (or collection of routines) that, along with their implementation input flows, give an organization's management a set of decision options to produce important results of a particular type”. The capability-centered view suggests that capabilities can be organized as a hierarchy ranging from lower-order capabilities to higher-order capabilities (Helfat and Peteraf 2003; Winter 2003; Helfat et al. 2007). Lower-order capabilities allow the firm to produce and sell on a day-to-day basis and maintain the operational status quo (Winter 2003). According to Grant (1996), the combination of these capabilities forms higher-order capabilities, which improve the performance or achieve a competitive advantage for firms by allowing them to "intentionally create, extend and modify" organizational operations to adapt to the dynamics and demands of the markets (Daniel et al. 2014).

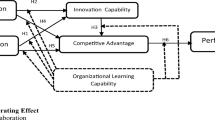

From this point of view, a significant volume of studies consider ICT capabilities to be lower-order capabilities that can influence value creation in firms, not by their own action or in isolation but through capabilities of greater complexity (Melville et al. 2004; Mao and Quan 2015; Felipe et al. 2020). Information systems experts call this phenomenon the mediation hypothesis (Benitez-Amado and Walczuch 2012). It has been established that resources and ICT capabilities will impact the firm's performance through an indirect mediation effect on other capabilities of a higher order. The information systems literature has provided various definitions of ICT capabilities, although it is understood that these capabilities refer to business skills that utilize the various technologies for their operations. However, to be consistent with the vision of ICT-enabled capabilities (Rai et al. 2006), this study uses Bharadwaj's (2000) definition, which elaborates ICT-enabled capabilities as those capabilities resulting from the mobilization and deployment of ICT-based resources in combination with other resources and capabilities. In this way, this study considers that the integrated ICT capabilities in Ibero-American SMEs will be deployed and enable other higher order capabilities—such as knowledge management and product innovation flexibility—which will have a direct or indirect effect on their performance. Accordingly, Fig. 1 presents the research model of this study. Subsequently, the conceptual variables that structure the model are described, and then the hypotheses are presented.

2.1 ICT capabilities

It is well known that ICT has become a key resource in firms. Although small firms often have more difficulty incorporating them into their processes (Riemenschneider et al. 2003), some authors have provided different evidence on their effect on business performance (Rai et al. 2006; Felipe et al. 2020). However, firms that successfully integrate and develop ICT management and value creation capabilities are scarce. A good number of researchers have advanced in providing explanations on how these capabilities contribute to improving organizational performance (Uwizeyemungu et al. 2018). In general, these studies show that these capabilities support and encourage the development of more complex operational processes. From this point of view, ICT capabilities are considered fundamental and lower order capabilities that can develop/enable other more complex or higher order capabilities, which are the ones that directly contribute to the creation of the commercial value of enterprises (Benitez-Amado and Walczuch 2012). In other words, the relationship or effect between ICT capabilities and firm performance is often mediated by higher-order capabilities, such as strategic flexibility (Chen et al. 2017), organizational agility (Sambamurthy et al. 2003), and management capabilities (Mithas et al. 2011), among others. In the literature on ICT capabilities, several conceptualizations, such as IT infrastructure, IT management, e-commerce or ERP capabilities, are found (Raymond et al. 2018), although that study generally takes a broad view without taking into account relevant characteristics, such as the size or experience of firms (Raymond et al. 2018). For example, it has been mentioned that SMEs face limitations in shaping robust ICT capabilities, but there are still no clear conceptualizations for this particular type of enterprise. Taking this into account, in this study, ICT capabilities are conceptualized as a second-order construct with two dimensions that try to explain the use of ICT by SMEs in both their internal practices and in their relationship with stakeholders and the environment (Inkinen et al. 2015).

2.2 Knowledge management capability

Given that it is a source for achieving competitive advantage, knowledge has become a key resource in organizations (Andreeva and Kianto 2011). An adequate capability to manage knowledge allows firms to better face the dynamism and competitive environment of the markets, providing them with options to create value and improve their performance (Del Giudice 2016). Given its relevance, experts have placed special interest in the process of knowledge management as an organizational capability (Tanriverdi 2005; Cai et al. 2019), and currently, there is an important stock of literature at the intersection of KM, business and management (Gaviria-Marin et al. 2019). However, despite the extensive literature, the discipline lacks a universally accepted conceptualization (Ode and Ayavoo 2020). KM capability is assumed to involve a series of sequential and synergistic processes that allow firms to create business value (Mao et al. 2016), and this assumption has led experts to consider KM a higher-order capability (Rai et al. 2006). There is evidence that by technologically favoring the acquisition, transfer and storage of information from the environment and between individuals/departments within an organization (Song et al. 2006), higher-order capabilities, such as KM, are developed/enabled by lower-order capabilities, such as ICT capabilities (Mitchell 2003). In this sense, experts often position KM capability in a mediating role between ICT and variables such as organizational performance, but in the context of SMEs, this role is still not entirely clear (Soto-Acosta et al. 2018).

The conceptualizations of KM capability are diverse (Tanriverdi 2005; Cai et al. 2019). Nonaka (Nonaka 1994), however, provided important guidance by mentioning that KM is “a multifaceted concept with multi-layered meanings”. Therefore, the authors conceptualized KM as a sequence of activities/practices. For example, Pérez-López and Alegre (2012) and Soto-Acosta et al. (2018) conceptualize KM as a process of three interdependent activities, namely, acquisition/creation, transfer/dissemination, and use. Recently, Xie et al. (2018) identified the KM process as a series of activities that involve the acquisition, assimilation, transformation and exploitation of knowledge. In this study, KM capabilities are conceptualized as a second-order multidimensional variable involving knowledge acquisition, transfer and use.

Knowledge acquisition refers to the activities carried out in the firm to obtain knowledge of both the external environment and those environments generated internally (Pérez‐López and Alegre 2012). Knowledge transfer refers to the processes used to exchange/share knowledge between different individuals/departments of the firm (Liao et al. 2011). Finally, the use of knowledge refers to the application of the knowledge base acquired and transferred between the members of the organization (Soto-Acosta et al. 2018). The literature agrees that the processes involved in KM capability are synergistically and complementarily interrelated and can favor the good performance of firms.

2.3 Product innovation flexibility

Currently, to address competitive environments, businesses must improve their responsiveness. Das (2011) points out that implementing flexibility measures allows firms a better receptivity, which favors the resolution of problems in the face of uncertainty, enabling an improvement in firm performance. In the management field, flexibility refers to the capability to change structural/strategic/operational schemes to facilitate creative responses that promote information processing, innovation, and the ability to respond to market demands or uncertainty, among other situations (Damanpour 1992; Dobrzykowski et al. 2015; Perry-Smith and Mannucci 2017; Kumar and Singh 2019; Shukla and Sushil 2020). In organizations, flexibility is therefore considered an important strategic capability (Malhotra and MacKelprang 2012), which has motivated researchers to conceptualize various flexibility measures, including strategic flexibility (Bamel and Bamel 2018; Brozovic 2018), human resource flexibility (Way et al. 2015; Martínez-Sánchez et al. 2019), supply chain flexibility (Beamon 1999; Das 2011), information systems flexibility (Kumar and Stylianou 2014), and manufacturing flexibility (Oke 2013), among others. In this study, we used a manufacturing flexibility sub-measure, also known as mix flexibility (Oke 2013) or product innovation flexibility (PIF) (Liao and Barnes 2015), which we adapted in a generic way to the production of both goods and services.

Product innovation flexibility is considered a higher-order capability that is linked to corporate strategy, marketing, innovation and business performance (Braunscheidel and Suresh 2009). This flexibility variable has been conceptualized in different ways, but in general, it focuses on the capabilities of companies to generate rapid changes in the development and production of products/services and thus meet customer requests. For example, Berry and Cooper (1999) defined it as the capability to produce a wide range of products or variants with low switching costs. Zhang et al. (2003) and later Oke (2013) defined it as the ability of firms to produce different combinations of products/services efficiently and effectively given a certain capability. PIF scholars agree that to implement flexibility, firms must evaluate the configuration of the operational/production system so as not to make major modifications to the firm's facilities or production system. PIF implies, in this sense, aligning the firm's production strategies to respond to market needs/demands (Zhang et al. 2003). In other words, this capability is oriented towards the external environment, specifically towards customers. To respond to market needs, up-to-date information/knowledge of market trends must be maintained by firms, which can increase customer satisfaction, sales growth and thus business performance (Zhang et al. 2003; Braunscheidel and Suresh 2009).

2.4 Business performance

Business performance is key to the survival of companies and is often used as an object of study when considering different disciplines in the field of business (Singh et al. 2016). The study on business performance seeks to explain the different factors that can help firms improve their performance and survival in the long term (Richard et al. 2009). Even so, definitions and performance measures are diverse, and there is no unified criterion in the literature to conceptualize and measure this variable (Richard et al. 2009). In an effort to guide the study of business performance, researchers have developed some classifications of performance types. Among them, reference is made to both objective and subjective performance measures (Wall et al. 2004; Singh et al. 2016). Objective performance measures, such as productivity, return on assets (ROA), or return on equity (ROE), are secondary data traditionally obtained from external records and not directly from the perception of the respondents (Wall et al. 2004). In contrast, subjective performance measures, such as market performance, innovation performance, and service quality, are based on opinions or perceptions that are collected through a survey or interviews (Gunday et al., 2011; Singh et al., 2016). The use of one type or another of these performance measures depends on the limitations that researchers find in attempting to access the objective information of the firms, which in the case of smaller firms and depending on the country of origin, are not always required to disclose their financial information (Razouk 2011), preventing the access to and comparability of these data. Taking this information into account, in this study, we focus on three subjective performance measures, namely, innovation performance, sales growth, and non-financial performance.

The literature recognizes innovation performance as one of the most important drivers of the measures of business performance (Hagedoorn and Cloodt 2003; Gunday et al. 2011). There are a wide variety of conceptualizations and measures of innovative performance, but there is no clarity or set of unified criteria for analyzing this measure of business performance, since studies tend to conceptualize it according to factors, such as industry or company size (Hagedoorn and Cloodt 2003). For example, Hagedoorn and Cloodt (2003) point out that innovation performance is a composite and integrative construct that is conceptualized by indicators, such as new product announcements, new patents, new projects or organizational arrangements. Gimenez-Fernandez et al. (2020) study innovation performance in small firms and measure it as the proportion of turnover resulting from new or improved products that the firm has introduced in the market in the last 3 years. Some years earlier, for this construct, Gunday et al. (2011) used a good measure, which goes beyond traditional conceptualizations and measures innovation performance as a result of the overall efforts made by firms to renew/improve aspects involving management practices, process changes, product/service changes and marketing. Despite the wide variety of constructs and measures in the literature, most scientific evidence agrees that innovation performance has an effect on firm growth and profitability (Saunila 2020). In this study, we adopt the conceptualization by Gunday et al., (2011), who suggest that innovation performance acts as a variable that exerts a positive effect resulting from the interaction of organizational variables on other business performance variables. Hence, in this study, we suggest that the synergistic interaction between capabilities of different orders (ICT capabilities, PIF and KM capabilities) will have an effect on other business performance variables (such as sales growth and non-financial performance) through innovation performance.

Finally, sales growth and non-financial performance are other performance variables used in this study. The former is a subjective indicator widely used in the management and marketing literature (Wales et al. 2020). Despite the subjective conceptualization, this indicator has been pointed out as an accurate indicator of business performance (Dzenopoljac et al. 2017). In this study, given the international nature of the sample and the complexities of accessing objective SME data, sales growth was conceptualized as the percentage change in sales from 2015 to 2016. Finally, non-financial performance is a measure that was adapted to assess the overall performance of the firm from previous years. Performance measures similar to those involved in this study have been used quite frequently in previous research (Bradley et al. 2012; Roach et al. 2016). Some researchers (see for example, Coram et al. 2011; Darroch and Darroch 2015; Liao et al. 2016) point out that this measure provides relevant information that reflects the value creation of firms.

3 Hypotheses development

3.1 The influence of ICT capabilities on higher-order organizational capabilities

The dynamics of the environment and the abundance of information demarcate a business reality different from that of past years (Knight 2000; Mithas et al. 2011). In recent years, ICT has taken on a more important role in organizations, which have had to implement/improve their capabilities to operate new technologies. In the business environment, ICT capabilities are considered lower-order capabilities that are useful for developing/enabling other higher-order capabilities (Rai et al. 2006).

Previous research has shown that SMEs do not take advantage of the full potential of ICT solutions as much as large firms do. During the last decade, technological progress has motivated small businesses to venture into the adoption of ICT (Gaviria-Marin and Cruz-Cázares 2020). However, these firms still need to implement/enhance capabilities to manage the technologies and achieve the desired effect on the business. Among these motivations, we can highlight the interest to (a) take advantage of technological opportunities (Leten et al. 2016); (b) incentivize the growth and profitability of the firm (Bulchand-Gidumal and Melián-González 2011; Pearlson and Saunders 2013; Hao and Song 2016); and (c) strengthen/develop/enable other capabilities of greater complexity or higher order (Felipe et al. 2020), such as the KM capability and product innovation flexibility (Turban et al. 2011).

In general, ICT has become important because it facilitates the communication between company departments, as well as with the various other stakeholders of the company, favoring collaboration and knowledge acquisition in the firm (Cai et al. 2019). Favoring the use/exploitation of knowledge and organizational learning, these capabilities can also be used for the management and storage of sensitive company information/knowledge (Rehman et al. 2020). They are often used to capture market information and analyze trends in the demands of potential customers (Wei et al. 2017). This suggests that companies that develop skills in the use of ICT may be motivated to make their design/production processes for new products/services more flexible. However, the effect of ICT capabilities on flexibility has not been investigated in depth in the literature (Devaraj et al. 2012). In this study, we address this gap. Therefore, considering the above, the following hypotheses are suggested.

H1

ICT capabilities have a positive effect on knowledge management capability.

H2

ICT capabilities have a positive effect on product innovation flexibility.

Given its effect on innovation and performance, the flexibility concept has gained importance in firms. Experts have conceptualized various types of flexibility related to various subdisciplines in the business area. In this study, we used an adaptation of the concept of mix flexibility (Slack 1991; Slack and Correa 1992; Zhang et al. 2003), which is used by Liao and Barnes (2015), who call this concept product innovation flexibility (PIF). According to authors, such as Oke (2013) and Liao and Barnes (2015), PIF is a tactical capability that involves a moderate degree of knowledge, commitment and effort to efficiently and effectively produce different product/service combinations.

Zhang et al. (2003) note that this type of flexibility is oriented to the external environment of the company, specifically to customers. In fact, companies with PIF capabilities quickly adapt their processes to produce new products/services according to customer or market needs, which directly affects the firm's competitiveness and performance (Braunscheidel and Suresh 2009; Liao and Barnes 2015). However, we suggest that implementing PIF involves advanced information or knowledge management, which will allow the firms to analyze and capture market needs and respond to new customer segments with new products or services (Malhotra and MacKelprang 2012). In addition, ICT capabilities are expected to facilitate the firm's information/knowledge management processes and allow for more flexible decision-making on the development according to specific customer needs, of new or modified products/services (Lesser and Prusak 2001). Therefore, considering the above, the following hypothesis is presented.

H3

Knowledge management capabilities mediate the relationship between ICT capabilities and product innovation flexibility.

3.2 Lower- and higher-order capabilities and their effect on organizational performance

In this document, three business performance indicators in particular are used. These dimensions are innovation performance, sales growth and non-financial performance. As previously mentioned, in this study, we follow Gunday et al. (2011) and use the innovation performance variable as a predictor of other firm performance variables.

3.2.1 The effect of lower-order capabilities on innovation performance

According to Gunday et al., (2011) good innovative performance is the result of firms having established an organizational climate oriented to learning and to making continuous and systematic efforts to adapt to changes in the environment and market. Some of these business efforts are related to the acquisition/implementation of ICT and the strengthening of the firms’ capabilities to manage this technology, since it facilitate the creation of value and therefore enable the firm to obtain high innovation performance (Parida and Örtqvist 2015). For example, ICT can favor greater efficiency in communication and work between the departments of a firm. It can also facilitate the reduction of costs associated with the management of the human resources of firms (Benitez-Amado and Walczuch 2012). Some studies, such as that of Nieto and Fernández (2005), point out that small firms with ICT capabilities can improve their market intelligence practices by facilitating the acquisition of information about a specific customer segment or a potential market niche, which can facilitate some innovative processes, such as the adaptation of their products or services and the implementation of new sales techniques, such as e-commerce. Therefore, taking into account the above, the following hypotheses are suggested.

H4

ICT capabilities have a positive effect on innovation performance.

3.2.2 The effect of higher-order capabilities on organizational performance

In general, although there is a positive consensus, the literature does not clearly show the effect of knowledge management on firm performance (Heisig et al. 2016; Gaviria-Marin et al. 2019). This is likely a consequence of the various conceptualizations of business performance that exist in the literature. For example, the study by Lin and Kuo (2007) analyzes the relationship between KM and overall firm performance by measuring market performance and human resource performance. Likewise, in an analysis by Liu et al. (2004), the effect of KM capability on the competitiveness of firms was measured in terms of non-financial indicators. Other articles, such as Salojärvi et al., (2005), found that KM's maturity correlates positively with the firms' sales growth measures. Finally, in a more recent study, Kianto et al. (2017) showed evidence that KM capability influences the market performance and the sales growth of firms. In light of this evidence, this study suggests that KM capability will have a positive effect on performance measures, such as sales growth and the non-financial performance of SMEs. Therefore, taking into account the above, the following hypotheses are suggested.

H5

Knowledge management capability is positively related to sales growth.

H6

Knowledge management capability is positively related to non-financial performance.

On the other hand, as a consequence of the demands of the market, firms are often driven to make their production processes more flexible. Hence, this ability to respond to market demand by making its production processes more flexible is a critical firm capability for survival that fits the structures of SMEs (Xie 2012). Some studies, such as Ebben and Johnson (2005), associated the concept of flexibility with the elaboration/design of products/services on demand, which is the variability issue to which a firm must respond. This type of flexibility has received various names, such as product flexibility (Ebben and Johnson 2005), flexibility of product innovation (Liao and Barnes 2015), mix flexibility (Zhang et al. 2003) or external flexibility (Upton 1994). Being customer or externally oriented, companies require the acquisition and analysis of an adequate level of market knowledge/information, which would lead them to make decisions to quickly adapt their product development processes (Oke 2013). Given this complexity, it has been suggested that implementing PIF would enable companies to respond to customer demands/needs effectively and efficiently, which could have an effect on increasing their sales and non-financial performance. Therefore, based on the above, the following hypotheses are presented.

H7

Product innovation flexibility is positively related to sales growth.

H8

Product innovation flexibility is positively related to non-financial performance.

3.2.3 The mediating effect of higher-order capabilities on the relationship between ICT capabilities and innovation performance

ICT has enabled firms to access and utilize a large volume of knowledge/information that has the potential to improve innovation performance (Bhatt et al. 2005; Soto-Acosta et al. 2018). For example, Giudice et al. (2016) point out that ICT favors the exchange of information and knowledge among company employees, which promotes the generation of a more participatory and innovative culture. Recently, Braojos et al. (2019) found that the opinions that customers provide about a product or service through websites or social networks can motivate entrepreneurs to develop new products/services or improve existing ones. In this way, the information/knowledge often captured by technological tools is an important source for the development of new product or service ideas (Parida and Örtqvist 2015). However, these examples suggest that to capture information from different stakeholders and successfully implement different types of innovation (which implies obtaining good innovative performance), it is not enough for companies to have adequate technological support; they must also develop capabilities to manage information and knowledge (Yousef Obeidat et al. 2016).

On the other hand, some authors, such as Oke (2013), suggest that some aspects related to production, such as product innovation flexibility, could have important effects on innovation outcomes. In fact, it has been argued in the literature that in competitive environments, flexibility is a fundamental capacity to achieve innovation indicators (Bolwijn and Kumpe 1990; Thomke et al. 1998; Oke 2013). In this sense, small firms that generally lack resources/capabilities and operate under significant levels of uncertainty tend to be more flexible in their decision making when making strategic/operational changes and implementing some type of innovation in their products/services (Broekaert et al. 2016). However, to make decisions regarding flexibility in product/service development, firms require technologies and information systems that provide key information to support those decisions. ICT capabilities also involve the owner's, manager's or area manager's abilities to access and analyze information obtained from digital platforms or systems, allowing him/her thereby to make timely decisions regarding the creation/design/change of processes, products or services and to respond to customer demands (Bi et al. 2019). Given the above, in this study, we postulate that ICT capabilities can foster the flexibility to rapidly design/produce new products/services and influence the innovation performance of firms. Despite theoretical efforts on the concept of product innovation flexibility or mix flexibility, few studies have delved into their mediating role in the relationship between ICT capabilities and innovation performance.

Taking into account this background, in this study, we expect the effects of ICT capabilities on the innovation performance of SMEs to be reflected through the mediation of higher-order capabilities, such as KM and PIF. Therefore, the following hypotheses are suggested.

H9

Knowledge management capability mediates the relationship between ICT capabilities and innovation performance.

H10

Product innovation flexibility mediates the relationship between ICT capabilities and innovation performance.

3.2.4 The mediating role of innovation performance in the influence of capabilities on organizational performance

The RBV literature states that firms that synergistically combine their resources and capabilities can achieve high levels of innovative performance (Curado et al. 2018). Innovation performance is a multidimensional concept that lacks a general conceptualization in the literature (Hagedoorn and Cloodt 2003). In fact, some authors, such as Dewangan and Godse (2014), point out that the heterogeneity in the measurement of innovation implies that firms also lack clarity about how to measure the performance of their innovation processes. Despite this, there is consensus in the literature that innovative performance is an important variable of organizational performance and that it also acts as an antecedent of other performance variables (see for example, Gunday et al., 2011). In other words, innovation performance manages to capture the climate, innovative culture, and other organizational factors that motivate firms to make efforts and commit resources to develop innovation in different areas, which will end up having an effect on other performance measures. This also suggests that to be successful in innovation performance, a synergistic interaction between the different resources and capabilities of the firm must exist (Newey and Zahra 2009; Parida and Örtqvist 2015).

One of these resources/capabilities is knowledge, and the ability to manage it (i.e., the knowledge management capability) has been continuously linked to business innovation performance (Zia 2020). Firms with ICT capabilities can adequately capture and manage information about the market and their customers, enabling them to develop appropriate innovation processes to satisfy their customers. In this sense, Parida et al. (2017) suggest that firms with good innovative performance are customer-oriented and have a greater tendency to use systems to manage information/knowledge, which makes it easier for them to understand market trends/needs. In other words, firms that manage information and are concerned with innovation are able to satisfy their customers and capture new customers, leading to sales growth and overall organizational performance (Wang and Wei 2005). From the above, we postulate that through the innovation performance of SMEs, knowledge management will have an indirect effect on sales growth and non-financial performance.

According to Oke (2013), product innovation flexibility is a capability that is oriented towards the external environment, specifically customers. By implementing this capability, SMEs learn to deal more quickly with uncertainty and particular customer demands. To make the development of new products/services more flexible, firms, particularly smaller ones, must build/maintain a close relationship with customers, which improves the chances of retaining and satisfying them (Parida et al. 2017). Note that PIF involves efficiently and effectively making rapid changes in the innovation process, production and launch of new products/services (Liao and Barnes 2015), facilitating thereby the obtaining of good innovation performance (Oke 2013). Finally, this allows us to postulate that this flexibility can improve the overall innovation performance of SMEs, which will have a direct effect on sales growth and their non-financial performance.

Consequently, in this study, we postulate that higher-order capabilities, such as KM and PIF, will have a positive effect on organizational performance through innovation performance. Therefore, the following hypotheses are suggested.

H11

Innovation performance mediates the relationship between knowledge management capability and the business's sales growth.

H12

Innovation performance mediates the relationship between knowledge management capability and the non-financial performance of the business.

H13

Innovation performance mediates the relationship between product innovation flexibility and the business's sales growth.

H14

Innovation performance mediates the relationship between product innovation flexibility and the non-financial performance of the business.

4 Methodology

4.1 Research design and data collection

For our study, we focused on a sample of Ibero-American SMEs. We adopted the amplest definition for SMEs provided by European Union descriptions, i.e., firms with fewer than 250 employees (Raymond and St-Pierre 2010). A structured questionnaire was designed and tested twice to improve the quality and response rates for data collection. The first test was applied to four Ph.D. students and four researchers, whose comments helped us adapt some of the questions. Subsequently, the questionnaire was sent to thirteen entrepreneurs. Two of them were PhDs and owned SMEs in those countries. Everyone's contributions allowed for small modifications to and validation of the questionnaire, which was then distributed by email by using the Qualtrics platform. Due to their sufficient knowledge of each of the items consulted, particularly those related to ICT resource investment decisions, managers, executives, and owners of SMEs were the focus of the questionnaire.

The questionnaire was distributed between November 2016 and February 2017 to firms in Colombia, Chile, and Spain. We found these firms in online business directories; thus, we assumed they had ICT-related capabilities. In total, 1,450 questionnaires were sent. Three reminders were also sent out to increase the response rates of the questionnaire. After this process, 137 questionnaires were received, of which 130 were valid, representing a response rate of 9%. The sample showed that 60% of the respondents held management positions, 15% were responsible for ICT, 14% were responsible for communications and marketing, 3% were responsible for human resources, and 8% held other positions.

4.2 Measurement of variables

This research model is conceptualized through 6 variables extracted from previous studies that have validated these measurements. Some items were slightly modified to adapt them to language and context. The variable representing lower-order capabilities is denoted by ICT capabilities, while KM and PIF are variables denoting higher-order capabilities. Finally, business performance is composed of three variables represented first by innovation performance (INP), then by sales growth (SGP), and non-financial performance (NFP). The choice of these variables is consistent with the literature that provides robust evidence to postulate that ICT capabilities impact enterprise performance indirectly through higher-order capabilities, such as KM and NFP. Appendix 1 provides an overview of each of the dimensions and their items.

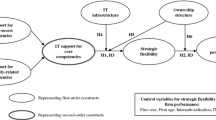

4.2.1 ICT capabilities

Authors such as Bharadwaj (2000) and Chen et al. (2015) point out that ICT involves a variety of tools that can be implemented in organizations, and it would thus be beneficial and more accurate to conceptualize the construct more broadly. Therefore, in this study, ICT capabilities are based on these authors' vision and are treated as second-order constructs composed of two dimensions. First, technological capability is a 5-item construct validated in the study by Zhou and Wu (2010) and attempts to measure the firms' capabilities regarding the acquisition and mastery of technologies compared with those of the competition. The second construct comprises five items and is based on the study by Inkinen et al. (2015). They analyzed the practical capabilities of ICT in terms of the operational capabilities of firms through use of ICT. A 7-point Likert-type scale was used in both dimensions, ranging from 1 (totally disagree) to 7 (totally agree). In this study, it is important to consider ICT capabilities as a second-order construct since they are lower-order capabilities that according to our model, impact higher-order capabilities, such as KM or PIF, that involve and require broader operational processes. As such, incorporating a single component of ICT capabilities may not be sufficiently robust.

4.2.2 KM capability

Recent studies focusing on KM capability refer to this capability as a higher-order and multidimensional variable or construct since it involves various stages of the knowledge management process. Although there are several conceptualizations of KM, this study is supported by the definitions of Andreeva and Kianto (2011) and Pérez-López and Alegre (2012), which elaborate on KM as involving a process that involves the acquisition, use, and transfer of knowledge. Therefore, in this study, we treat KM capability as a second-order construct, in which each construct represents a phase of the KM process. Thus, knowledge acquisition (KA) and knowledge use (KU) were measures obtained from the study of Pérez-López and Alegre (2012), while the measure of knowledge transfer (KT) was obtained from Andreeva and Kianto (2011). A 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) was used for all dimensions. Finally, we believe that analyzing this variable as a second-order construct is advantageous since it manages to capture a large part of the commonalities shared in the KM process phases.

4.2.3 Product innovation flexibility

In this study, we adapt the PIF construct as a variable that attempts to obtain information on the capability of firms to develop changes in the design of products or services according to the demands of the environment and to launch them efficiently in the market (Liao and Barnes 2015). Note that PIF differs from innovation performance in that it focuses on the firm's willingness to flexibly develop its products/services, whereas the innovation performance variable generally captures the outcome of the different types of innovation that firms undertake. From this perspective and given the complexity of implementing flexibility processes, this variable is seen as a higher-order capability (Bi et al. 2019). This 5-item scale was obtained from Liao and Barnes (Liao and Barnes 2015), and for all items, a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) was used.

4.2.4 Business performance

Considering our sample's characteristics and to show the effect of capabilities of a different order, it would be useful to approach the firm's performance more broadly, taking into account different scales of measure. Therefore, this study uses different measures of subjective performance.

The first of these refers to innovation performance measured through a four-item scale, an approach validated by Inkinen et al. (2015). As previously mentioned, this measure attempts to capture in a general way the result of the implementation of different types of innovation in firms. For the innovation performance items, a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) was used. The second measure is sales growth, adapted from Mansury and Love (2008) and Roach et al., (2016). This indicator is based on the percentage of increase in sales compared to the sales of the previous two years. Comparative approaches with other periods can help entrepreneurs more accurately assess and answer questions related to their firms' performance (Singh et al. 2016). Furthermore, according to some researchers, this type of performance indicator is relevant since it reflects the firm's market advantage (Yam et al. 2004; Kellermanns and Eddleston 2006; Wales et al. 2013; Rakthin et al. 2016). The third measure, non-financial performance, is a subjective indicator adapted from Jaworski and Kohli (1993) and Roach et al., (2016). This measure is measured with a 7-point Likert scale that ranges from 1 (totally disagree) to 7 (totally agree), and the respondents are asked to report on operational performance during the previous years. These last two self-reported measures could be considered unreliable (Meier et al. 2012) or could have some managerial bias. However, authors, such as Gunday et al. (2011), point out that given the familiarity that employers have with performance data, using these types of subjective and self-reported measures are usually quite accurate,. Furthermore, the use of these measures is a frequent practice in the business literature (Khazanchi et al. 2007).

4.2.5 Control variables

Finally, this study includes two control variables that could influence business performance. These include the size of the firm, a variable measured by the number of full-time employees (Liu and Deng 2015), and the age of the firm, a variable understood as the difference between the first year of establishment of the firm and the year of obtaining the data (Martinez-Conesa et al. 2017). The query and consultation on the year of the firm's founding facilitated this last variable's calculation.

4.3 Data analysis

The model proposed in this study is tested through the technique of partial least squares (PLS) and structural equations (SEM), both frequently used in the business sciences (Hair et al. 2019a). According to Rehman et al. (2020), the PLS technique is more robust and presents fewer statistical problems than SEM techniques based on covariance. Furthermore, it is more suitable for testing complex relationships between formative or reflective constructs, and it can also be adapted to the nonnormality of small sample sizes (Chen et al. 2015). This methodology also provides a flexible environment for studies with multiple block structures of observed variables. Several authors point out that PLS-SEM contributes to the evaluation of complex theories and incorporates models (confirmatory or explanatory) with simultaneous estimates of direct and indirect effects (mediators or moderators) among multiple constructs of a different order (Rigdon 2016; Ringle et al. 2020). In this study, we used SmartPLS 3.2.8 software to test our theoretical model.

5 Results analysis

Note that PLS can simultaneously estimate both the measurement parameters and the structural model. However, the model's estimation must be carried out in two stages: the analysis of the measurement model and the analysis of the structural model. The first one—the measurement model—through an analysis between the indicators and their respective construct, focuses on examining the scales' adequacy. The second—structural model analysis—examines the relationships between the constructs that are part of the structural model.

5.1 Analysis of the measurement model

First, a factorial analysis of the different variables that structure the theoretical model was carried out. This allowed us to discard the indicators that were not correlated with the scales of each construct. After this, the exploratory analysis revealed the unidimensionality of all the constructs that were used; therefore, we proceeded to estimate the measurement model with PLS. Consistent with what has been pointed out by some researchers (Sharma et al. 2007; López et al. 2009), ICT capabilities and KM capability are conceived as second-order reflective constructs. Since PLS does not allow the representation of second-order factors, we proceeded to create and analyze them by using a step-by-step approach.

In the first step, all the first-order factors included in the model, as well as the factors and indicators that form the second-order constructs (ICT and KM), are included in a first analysis. In a first estimation of the constructs, tests of the reliability of the indicators, convergent validity and discriminant validity were carried out. According to the results of this first estimation, all variables showed individual reliability. Likewise, the composite reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE) indicators were found to be higher than 0.7 and 0.5, respectively. To assess discriminant validity, the Heterotrait-monotrait ratio method (Henseler et al. 2015) and the criteria of Fornell and Larcker (1981) were used. All HTMT values among the first-order constructs were below 0.85. In addition, the AVE values were higher than the squared correlation, thus confirming the existence of discriminant validity.

In the second step, the model is estimated with the factorial scores calculated in the first step for each of the first-order components. After the second-order variables are constructed, the adequacy of the measures of the second-order constructs model is estimated again in the following three steps. In the first step, the individual reliability of each element is analyzed through its loads (λ). The PLS factor loading evaluation criteria establish that higher values represent higher levels of reliability. In this sense, values between 0.6 and 0.9 vary from "acceptable to good" (Hair et al. 2019b). In our case, all factorial loads exceeded the minimum value recommended in the literature. The second stage consists of evaluating the scales of the constructs through the use of the traditional indicators of internal consistency, such as Cronbach's alpha, the composite reliability index (IFC), and convergent validity through the mean–variance extracted (AVE). The Cronbach's alpha values—measures used to check the questionnaire's internal consistency (Rehman et al. 2020)—were all higher than 0.6, which meets Nunnally’s (1978) criterion and confirms the reliability of the questionnaire. The convergent validity evaluates whether the items represent the same construct. In our analysis, the AVE values were all above 0.5, confirming convergent validity (Fornell and Larcker 1981). IFC indicates the consistency of the variables with respect to what is intended to be measured. In our study, IFC values in all variables exceeded the threshold of 0.7 (see Table 1).

In the third stage, a verification of discriminant validity is conducted. This indicator shows whether there is a difference between a construct and the rest that form the model's structure. In PLS, the most accepted method for determining discriminant validity is the comparison between AVE values and the square value of the correlations of each variable (Henseler et al. 2015). Thus, for discriminant validity to exist, the AVE values must be greater than the squared correlations. Finally, the analysis shows that the HTMT ratios are below the suggested threshold of 0.85 (Henseler et al. 2015). Taking into account these criteria, it can be seen that the model has adequate discriminant validity (see Table 2).

5.2 Analysis of the structural model

A bootstrapping procedure with 6,000 subsamples was used to recognize the coefficients' statistical significance (Nevitt and Hancock 2001). The percentile method was bounded by a 5% confidence margin. The structural model was examined through the significance of the coefficients λ, the model dependency coefficients (β), and by observing the values of the explained variance (R2) of the dependent variables. Finally, the Stone-Geisser test (Q2) was used to evaluate the dependent variables' predictive relevance. According to Henseler et al., (2009), this last measure evaluates the predictive capacity of a research model. In general, it is considered that if the value of Q2 is positive, the constructs have predictive relevance (Fornell and Cha 1994; Hair et al. 2016). In the test of the hypotheses of the model, Fig. 2 shows the trajectory of the coefficients and their statistical significance values. In addition, it is observed that the values of R2 and Q2 are positive, and it is therefore assumed that the model satisfies predictive relevance.

On the other hand, Table 3 shows the structural model's direct relationships between lower-order capabilities (ICT) and higher-order capabilities (KM and PIF). The results show support for hypotheses H1 and H2, finding that ICT capabilities directly and significantly affect higher-order capabilities, that is, in KM (β = 0.239, t-value = 2.694) and in PIF (β = 0.428, t-value = 5.805). Subsequently, the direct effects of ICT and INP capabilities are calculated. This result supports hypothesis 4 by finding that ICT capabilities have an effect on the firms' innovative performance (INP) (β = 0.230, t-value = 3.160).

The direct effects of higher-order capabilities and performance measures are also analyzed. In this case, it is observed that KM has no significant influence on SGP (β = − 0.077, t-value = 0.888), nor does it have a significant influence on NFP (β = 0.070, t-value = 0.843). Therefore, hypotheses H5 and H6 are rejected. PIF exerts a significant influence on SGP (β = 0.260, t-value = 2.705); therefore, hypothesis H7 is accepted. However, the same does not occur between the PIF and the NFP (β = 0.095, t-value = 0.918); therefore, hypothesis H8 is rejected.

The bootstrap procedure also allowed us to find estimates of the indirect effects (Preacher and Hayes 2004). The results of these relationships are shown in Table 4.

The estimates revealed that ICT influenced the PIF indirectly through KM (β = 0.040; t-value = 1.733), thus accepting hypothesis 3. The mediating role of KM in the relationship between ICT and innovation performance (INP) was proposed in hypothesis 9, whose results suggested a significant indirect relationship (β = 0.042; t-value = 1.899). Similarly, hypothesis 10 affirmed that PIF also plays a mediating role in the relationship between ICT and INP. The model estimate revealed a strong and significant indirect path (β = 0.183; t-value = 4.011). These results lead us to accept hypotheses 9 and 10.

Our study suggests that innovation performance mediates the relationships between higher-order capabilities (KM and PIF) and the other performance indicators (H11, H12, H13 and H14). In this sense, all indirect paths between these variables were positive and significant. Therefore, it is confirmed that innovation performance mediates the relationship of KM on sales growth (β = 0.038; t-value = 1.718) and on non-financial performance (β = 0.061; t-value = 2.354). Similarly, innovation performance mediates the relationship of PIF on sales growth (β = 0.092; t-value = 2.157) and on non-financial performance (β = 0.148; t-value = 2.892). Therefore, assumptions H11, H12, H13, and H14 are accepted (see Table 4).

On the other hand, we examined the influence of some control variables on the performance of the firms. The results generally indicate that the size of the SME has a significant and positive effect on both innovation performance (β = 0.194; t-value = 2.646) and sales growth (β = 0.159; t-value = 2.184). This suggests that larger SMEs may have more resources to develop innovative activities, which implies a growth in their products' sales. In terms of years of experience, older firms have better sales growth (β = 0.280; t-value = 3.577), suggesting that older SMEs achieve sales growth not by innovation performance. Here, other factors, such as customer loyalty, could explain this relationship. The other relationships between the control variables and the performance indicators were not significant in the model.

Finally, Fig. 2 shows the results of the structural model estimation, including the respective indicators of direct and indirect effects. The results reveal that ICT capabilities directly influence more complex or higher-order business capabilities, such as KM and PIF. In this sense, we observe coherence with the study by Felipe et al., (2020), in which they point out that ICT is a technology that enables other capabilities of a higher order. Note that, in general, the only significant and positive relationships between firm capabilities and performance indicators are those between ICT capabilities and innovation performance and between PIF and sales growth.

These results are consistent with those of the Parida and Örtqvist (2015) study. However, our model's mediation effects are interesting, specifically the results of the mediation effect of higher-order capabilities—KM and PIF—on performance measures, suggesting that the synergistic interaction between KM and PIF capabilities may have an effect on other performance indicators.

6 Discussions and conclusions

Our paper empirically examines the relationships between different types of business capabilities (lower- and higher-order) and their direct and indirect effects on the performance of Ibero-American SMEs. Specifically, we focus on ICT capabilities (a lower-order capability) as an enabling factor for more complex capabilities, such as KM and PIF. The analysis of the relationships between capabilities of different orders or hierarchies (Grant 1996) has been frequently studied in the literature (Sambamurthy et al. 2003; Benitez-Amado and Walczuch 2012; Bi et al. 2019; Felipe et al. 2020). Firm capabilities are heterogeneous, and the interaction effects between them, which add value to the firm, have not yet been fully studied. Some recent studies that have been developing a line of research focusing on ICT-enabled capabilities (Felipe et al. 2020) have called for more research to contribute to a better understanding of how ICT capabilities create value in a firm through other higher-order capabilities.

At the statistical level, the results of the PLS analysis of our study support the reliability and predictive validity of both the measurement model and the structural model that represents the entire sample of SMEs, as well as the subsamples generated to represent them. It can therefore be assumed that the dependent variables, i.e., the SMEs' performance variables, can be predicted by the model’s independent variables represented by ICT capabilities, product innovation flexibility and knowledge management capability. Given the fundamental role of SMEs in the different economies, the predictive adequacy of the model presented provides relevant information so that they can strengthen/develop their various capabilities and obtain better performance.

In this sense, our study's main contribution has been to provide new evidence on the synergistic and underlying effects between ICT capabilities and other important capabilities, such as KM and PIF, and their effect on SMEs' performance. From this perspective, by developing and estimating a complex theoretical model that integrates both first- and second-order constructs, we contribute to the flow of literature focused on SMEs and ICT-enabled capabilities.

Several conclusions derived from the results are presented below. First, ICT capabilities act as a factor that promotes improvements in the innovation performance of SMEs. However, it also does so through more complex capabilities, such as KM and PIF. In this sense, although several direct relationships could be evaluated based on ICT capabilities, it was important to propose mediation relationships between the different lower-order and higher-order capabilities. Several authors point out that lower-order capabilities can be important in creating the firms' value but cannot create this value by themselves since they need other higher-order capabilities (Rai et al. 2006). In line with this, our results provide evidence that ICT capabilities have a direct and indirect effect (through KM and PIF) on innovation performance, representing a relation known in the literature as complementary mediation (Hair et al. 2019a). The results regarding the direct effect between ICT and innovation performance are not strange and are consistent with studies such as Parida and Örtqvist (2015). Even so, our arguments about this significant relationship are that ICT capabilities facilitate access to information on the environment, which could promote the development of different types of innovation in Ibero-American SMEs. Regarding the complementary mediation relations between ICT capabilities and innovation performance, our results confirm the synergistic and enabling role ICT plays in improving the firms' performance through other higher-order capabilities (Kim et al. 2011).

Second, the results show a non-significant direct relationship between KM and the performance measures, particularly sales growth and non-financial performance. The literature usually indicates a positive relationship between these variables. However, there are some works with results that could support our findings (Zack et al. 2009). Some authors also highlight that the direct relationship between KM and business performance has some weaknesses (Dzenopoljac et al. 2017), particularly regarding variables that function as mediators between KM and performance (Omerzel 2010). Similarly, authors such as Kalling (2003) point out that KM practices do not necessarily imply a better performance of the organizations. However, KM processes have an indirect effect on the firm's performance through a set of other intermediate capabilities (Lee and Choi 2003). Some of the results of our model could shed light in this regard. For example, a significant relationship was found between KM and sales growth and non-financial performance through innovation performance. This suggests that when a firm has a better capacity to manage knowledge, it can develop and implement innovative activities that allow it to cope with environmental and market dynamism and improve different indicators of its performance.

Third, the results show disparate results between PIF and performance indicators. It is observed that there is a significant and positive relationship between PIF and sales growth but not between PIF and non-financial performance. PIF has been conceptualized as a higher-order capability enabled by lower capabilities such as ICT. The current dynamism of markets requires firms to implement flexible, innovative processes that respond to changing market needs. Logically, making decisions in favor of implementing flexible organizational processes can be a critical factor for the success of firms (Felipe et al. 2020). Nevertheless, one explanation for our findings is that the link between PIF and business performance can be situational (Wei et al. 2017). In other words, PIF may not improve the performance of the firm since it depends on the degree of complementation between flexibility and the firm strategy (Vokurka and O’Leary-Kelly 2000). Our results, however, show that the nonsignificant direct effects between PIF and some performance variables change when the mediating effect of innovative performance is included in the assessment of this relationship. This makes sense since some authors indicate that flexibility is a higher-order organizational capability that can bring value when combined with other capabilities, such as innovation (Zhou and Wu 2010). In fact, Bolwijn and Kumpe (1990) suggest that good innovation performance cannot be obtained without being flexible. Therefore, SMEs should strive to use their capabilities to flexibly develop their operations, as it could increase the overall performance of firms.

Fourth, this study provides evidence of the mediating role of innovation performance on other performance measures. Although SMEs tend to have considerable resource and capability limitations, these firms are usually more agile and flexible than their larger counterparts, which promotes and facilitates the implementation of different types of innovations (Gunday et al. 2011). Results similar to ours have been well studied and are often accepted in the context of SMEs (Roxas et al. 2014). However, as this study shows, SMEs need to strengthen their capabilities. The synergistic interaction among these capabilities will enable them to implement innovative activities and meet the market's changing demands and opportunities.

6.1 Practical implications

Our study presents some implications that could be useful for the owners and managers of small and medium enterprises. First, our study has confirmed the enabling role of ICT capabilities over other higher-order capabilities and, through these higher-order capabilities, over the performance of SMEs. Firms must not only allocate resources to integrate ICT into their processes but also understand that ICT can be an important success factor whenever they decide to implement or strengthen other more complex or higher-order capabilities. In fact, the integration and implementation of ICT can facilitate the implementation of knowledge management processes or product innovation flexibility. In this sense, entrepreneurs must recognize the potential of integrating ICT capabilities since these capabilities can facilitate communication with various actors in the environment (Bi et al. 2019), enabling the entrepreneurs to access new knowledge (Scuotto et al. 2017) and thus favoring the development of higher-order capabilities, such as learning (Abel 2015) and other intangible capabilities.

Second and in line with the above, firms must create clear processes to acquire and process the knowledge that is important to the organization. According to these results, the firms that achieve these competencies will be able to innovate more easily and obtain better performance. Currently, however, firms have unlimited access to various types of information and knowledge (Gaviria-Marin and Cruz-Cázares 2020), which could imply a risk, as they do not have the capacity to discriminate based on the quality of the different information sources that are integrated into the firm. This could negatively affect decision making in SMEs (Habjan et al. 2014). From this point of view and given the potential that has been demonstrated in this study, smaller firms should centralize the ICT integration responsibility in a department or individual and integrate it into the design/implementation of strategies and decision-making. Similarly, owners and managers should strengthen their ICT capabilities by recognizing that ICT is important in strategy development and elaboration (Felipe et al. 2020).

Finally, an important implication for policymakers is that they must continue to encourage the adoption and integration of ICT in SMEs. Our study provides evidence that ICT capabilities have the potential to catalyze other capabilities in firms. However, ICT incentive policies should not be restrictive. For example, governments must consider training the human capital of these firms, knowing that the ICT training of individuals can, among other outcomes, improve/facilitate the communication with various stakeholders, facilitate the individuals’ operational activities/work in the company, and enhance the conducting of effective information/knowledge management practices.

6.2 Limitations and future lines of research

Like any other study, this research has some inherent limitations. First, the sample size of 130 respondents was limited, although it met the minimum criteria suggested for testing with PLS-SEM. Note that in this study, we recognize the enabling role of ICT capabilities and the importance of other higher-order capabilities in SME performance. However, it is necessary to continue to analyze these relationships in greater depth and to explain other interactions not considered. In future studies, a larger sample size or a consideration of longitudinal data could better explain the relationships proposed in our model. We also recognize the potential use of qualitative methodologies to confirm the different relationships raised in this study.

Second, although the informants in our sample were mostly in positions of responsibility, only one informant per firm was surveyed. This can present data credibility and subjectivity issues, particularly concerning performance measures based on the respondent's perception. According to Bi et al. (2019), this type of issue is known as the susceptibility to reporting bias. In addition, it cannot be ignored that many employers protect objective or quantitative data, particularly those related to their performance (Singh et al. 2016). Therefore, future studies could consider a sample of multiple functional managers per firm, which would strengthen the reliability of the data regarding perceived performance.

Third, the sample data were collected from three countries with different development levels and different participation percentages. Therefore, future studies could take a representative sample of each economy to carry out cross-country studies, strengthen the generalizability of the model (Zhu et al. 2004) and provide more extensive information on the effects of the interaction of capabilities of different orders on the performance of SMEs. Thus, we recognize that this model may not fit the reality of enterprises in all countries. On the other hand, this study does not consider the institutional and contingent characteristics of each country. SMEs are influenced by external factors, such as public policies, cultural norms, or environmental turbulence. According to the SMEs' country of origin, these variables could promote or prevent the adoption and integration of ICT. Therefore, future studies could incorporate variables that capture the countries' institutional and contingent realities and analyze the effect of these realities on the adoption and integration of ICT capabilities in SMEs. Incorporating these measurement scales could help reduce the bias that may come from the origin of our sample data.

Fourth, we focus on creating value given by the synergistic effect between lower-order capabilities—such as ICT capabilities—and higher-order capabilities, such as knowledge management and product innovation flexibility. However, higher-order capabilities are varied, and the role of ICT capabilities over them remains to be explored (Benitez et al. 2018; Felipe et al. 2020). Given the current context, characterized by turbulence and uncertainty in the market (for example, due to the health emergency of COVID-19), future studies can analyze the enabling effect of ICT on other organizational level capabilities, such as learning or organizational agility (March 1999; Lu and Ramamurthy 2011) or strategic decision-making processes (Calabretta et al. 2017). From our understanding, these capabilities can be important when facing complex and uncertain environments. For example, in the face of unexpected events, ICT capabilities play a critical role in organizational agility to implement a digital transformation in business models. The interaction between ICT and the mentioned variables has not yet been studied, representing an interesting option to continue contributing to the literature.

Finally, our study does not take into account aspects related to the owner/manager, employees or other stakeholders. In the firm, both actors are relevant when implementing and developing capacities, both lower and higher order. The owner and manager, logically, greatly influence the development of capacities in their firms. In this sense, some studies have provided evidence that management leadership plays a key role in adopting and developing ICT capabilities and in the success of knowledge management (see for example, Luk 2009; Muhammed and Zaim 2020). Something similar can occur at the employee level, particularly in the effects that variables (such as commitment or multitasking orientation) can have on implementing more complex processes, such as knowledge management (Bellur et al. 2015; Muhammed and Zaim 2020). Similarly, other studies, such as those by Cegarra-Navarro (2005) and, more recently, Vătămănescu et al. (2020), have highlighted the role of the SMEs' strategic networks in innovative performance through KM capabilities. Therefore, future studies may incorporate into the analysis of this model the mediating and moderating effect of the owners’ and managers’ leadership skills, the commitment or multitasking orientation of SME employees, or the effect of stakeholders.

References

Abel MH (2015) Knowledge map-based web platform to facilitate organizational learning return of experiences. Comput Human Behav 51:960–966

Andreeva T, Kianto A (2011) Knowledge processes, knowledge-intensity and innovation: a moderated mediation analysis. J Knowl Manage 15:1016–1034

Bamel UK, Bamel N (2018) Organizational resources, KM process capability and strategic flexibility: a dynamic resource-capability perspective. J Knowl Manage 22:1555–1572

Barney J (1991) Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J Manage 17:99–120

Beamon BM (1999) Measuring supply chain performance. Int J Oper Prod Manage 19:275–292

Bellur S, Nowak KL, Hull KS (2015) Make it our time: in class multitaskers have lower academic performance. Comput Human Behav 53:63–70