Abstract

The use of cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging left atrial late gadolinium enhancement (LA LGE) is increasing for fibrosis evaluation though the use is still limited to specialized centres due to complex image acquisition and lack of consensus on image analyses. Analysis of LA LGE with image intensity ratio (IIR) (pixel intensity of atrial wall normalized by blood pool intensity) provides an objective method to obtain quantitative data on atrial fibrosis. A threshold between healthy myocardium and fibrosis of 1.2 has previously been established in 3T scans. The aim of the study was to reaffirm this threshold in 1.5T scans. LA LGE was performed using a 1.5T magnetic resonance scanner on: 11 lone-AF patients, 11 age-matched healthy volunteers (aged 27–44) and 11 elderly patients without known history of AF but varying degrees of comorbidities. Mean values of IIR for all healthy volunteers +2SD were set as upper limit of normality and was reproduced to 1.21 and the original IIR-threshold of 1.20 was maintained. The degree of fibrosis in lone-AF patients [median 9.0% (IQR 3.9–12.0)] was higher than in healthy volunteers [2.8% (1.3–8.3)] and even higher in elderly non-AF [20.1% (10.2–35.8), p = 0.001]. The previously established IIR-threshold of 1.2 was reaffirmed in 1.5T LA LGE scans. Patients with lone AF presented with increased degrees of atrial fibrosis compared to healthy volunteers in the same age-range. Elderly patients with no history of AF showed significantly higher degrees of fibrosis compared to both groups with younger individuals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The clinical demand for cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) and the corresponding scientific developments have been expanding during the past 20 years [1]. Late gadolinium enhancement is today a well-established method for detecting fibrosis in the ventricular myocardium [2]. Since its introduction in 2007 [3], CMR imaging of left atrial fibrosis with late gadolinium enhancement (LA LGE) has received increasing interest [4,5,6,7,8,9]. The method has proven valuable in detection of pre-ablation atrial fibrosis [4, 8, 10,11,12,13] but also in evaluation of ablation procedures and detection of possible gaps in ablation lines after pulmonary vein isolation [10, 12, 14,15,16].

Despite its many promising possibilities, LA LGE has remained a method reserved for highly specialized centres and previous studies have reported both positive [4, 8, 14, 15] as well as disappointing results [5, 7, 16,17,18,19]. The clinical adoption of LA LGE has been slowed by complex image acquisition protocols reflected in high exclusion rates of scans in clinical studies (9–32%) [4, 5, 8, 9, 13, 20] and furthermore of a lack of consensus on an objective image analysis method [21]. Initially, fibrotic areas were evaluated visually [3] but the need for an objective analysis method resulted in development of various reference-based analysis methods. Different anatomic regions have been used as reference; healthy atrial myocardium [11], nulled ventricular myocardium [19], fibrotic atrial myocardium [14], blood pool variability [12, 22] or blood intensity [23]. All methods aim to distinguish between healthy and fibrotic atrial myocardium. As the interstitial fibrosis prior to ablation in otherwise similar atrial fibrillation (AF) patient groups vary from 6 to 31% [4, 5, 12, 18, 20, 24,25,26,27] and in healthy volunteers from 1.7 to 8.9% [11, 27] with various analysis methods, there is an obvious need for an objective analysis method for continuous development of LA LGE and for obtaining trustworthy clinical results.

The image intensity ratio (IIR) analysis method of LA LGE uses the mean blood volume intensity as reference [23, 25]. By normalization with the mean blood pool intensity the variability due to timing and dose of contrast, renal function, coil proximity, and haematocrit is reduced and the IIR analysis method hence provides an objective assessment of LA LGE. The IIR analysis method was initially introduced by Khurram et al. who defined IIR thresholds based on electroanatomic mapping (EAM) [23]. The IIR analysis method has shown good consistency and absolute agreement when compared to other thresholding methods [6]. Based on data from healthy volunteers Benito et al. found an upper IIR threshold of 1.2 for healthy atrial myocardium [25]. The study by Benito et al. was performed on 3 Tesla (T) magnetic resonance (MRI) scanners and so far, this threshold has not been validated or reproduced at 1.5T. Currently 1.5T scanners are more widely used than 3T scanners for cardiac MRI. Although available data suggest that the field strengths provide similar results [6], differences in signal-to-noise and contrast-to-noise between the two field strengths may result in differences in measured tissue intensities [28]. This means that a validation of the thresholds in both field strengths is important before using the thresholds in large scale studies or clinical work [25].

The aim of this study was to reproduce the LA LGE IIR threshold found at 3T for healthy atrial myocardium in healthy volunteers scanned on a 1.5T MRI scanner.

Methods

Study population

A total of 33 participants were included for the study: 11 healthy volunteers, 11 patients with lone paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (AF) and 11 elderly patients.

The group of healthy volunteers served as reference for healthy tissue and were used for calculating the image intensity ratio (IIR) threshold at 1.5T. This group consisted of 11 healthy volunteers, age-matched to the below-mentioned lone AF patients. The healthy volunteers had no history of heart disease or other health conditions and did not receive prescription medication.

Two patient groups were included for verification of the threshold obtained: 11 patients with lone paroxysmal atrial fibrillation aged less than 45 years of age and no prior ablations and 11 elderly patients (minimum 70 years of age) with no history of AF but with various degrees of known diabetes mellitus, hypertension, congestive heart disease and/or previous stroke.

Exclusion criteria for all included participants were glomerular filtration rate < 60 mL/min, claustrophobia, known gadolinium allergy and implanted ferromagnetic metals.

All included participants were scanned for research purposes and provided written informed consent prior to inclusion. The study protocol conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki as reflected in a priori approval by the local ethics committee of the Capital Region of Denmark (Protocol Number H-1-2011-044 and H-4-2013-025).

Image acquisition

A 1.5T MRI scanner (Aera, Siemens Healthcare, Germany) with an 18-channel body coil was used to scan all included patients and healthy volunteers at Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen, Denmark. After scout sequences, long axis cine images (two-chamber, three-chamber and four-chamber) images were acquired for planning of a short axis stack and aid in delineation of chambers. An axial cine stack ranging from the basis to the aortic arch and a short axis cine stack covering the entire left ventricle were obtained for measurement of left atrial and left ventricular volumes, respectively (steady-state free precession cine sequences (8 mm; 2 mm gap; 25 phases; field of view (320–360) × 360 adjusted for each patient; matrix size [182–224) × (138–224)] at 10–15 s end-expiratory breath-holds).

The left atrial late gadolinium enhancement (LA LGE) scan was performed 20 min after bolus injection of 0.2 mmol/kg gadobutrol (Gadovist, Bayer, Berlin, Germany), with a maximum of 15 mmol in total [6]. The LA LGE scan consisted of a free-breathing respiration-navigator-gated 3D FLASH sequence with FatSat and ECG-gating (atrial end-diastole, determined from four chamber cine). Typical parameters were TR/TE 4.67/1.94 ms and bandwidth of 300 Hz. Inversion time was set according to a scout-sequence in a mid-ventricular image (270–310 ms). Flip angle was 20° and slice thickness 1.5 mm. Pixel spacing was 0.70 × 0.70 mm. No parallel-imaging was used. The mean acquisition time was 9 min 12 s ranging from 3 min 12 s to 16 min 27 s.

Image analyses

Volumetric measurements were performed in CVI42 (v. 5.6.6, Circle Cardiovascular Imaging Inc., Calgary, Canada). On short axis cine images left ventricular (LV) end-diastolic and end-systolic phases were traced manually at the endo- and epicardial border. Left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) was included in the blood pool; papillary muscles were excluded, using windowing for the endocardial border detection. Epicardium was delineated in both phases to compare left myocardial mass in end-diastole and end-systole. Left atrial (LA) volumes were traced manually on axial cine images. Left atrial appendage was included in left atrial volume. Minimum and maximum volumes were indexed to body surface area.

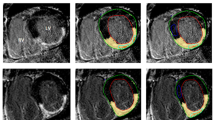

LA LGE scans were analysed using ADAS ® image post-processing software (Galgo Medical SL, Barcelona, Spain). On all axial images the atrial blood pool was initially segmented and atrial wall was interpolated automatically into a 3D shell, which was manually adjusted. To avoid epi- or endocardial artefacts or partial volume effects, the software was set to create a single mid-myocardial layer, which was manually adjusted according to MRI images to represent mid-atrial wall. Inflow artefacts were excluded. Pulmonary veins and mitral valves were excluded for fibrosis analyses. Pixel intensities were calculated automatically and shown on the 3D shell. Atrial wall pixel intensities and mean blood pool intensity were exported from ADAS ®. Image intensity ratio (IIR) values of all atrial wall pixels were calculated as atrial wall pixel intensity divided by mean blood pool intensity) (see Fig. 1).

Example of left atrial late gadolinium enhancement image. A original image. Blood intensity is 60 and image intensity ratio threshold hence (60 × 1.2 =) 72. B depicts segmented atrial wall, blue indicating atrial wall below threshold, red indicating atrial wall above threshold. RA right atrium, LA left atrium, Eso esophagus, LV left ventricle, Ao aorta

Image intensity ratio threshold

The threshold sought for was the discrimination between healthy and fibrotic atrial tissue. In accordance with Benito et al. [25], normal LA IIR was extracted from healthy volunteer scans. All IIR values from healthy volunteers were plotted in a histogram and the upper limit of normality (i.e. the threshold value for normal atrial myocardium vs. fibrotic myocardium) was defined as the mean IIR value + 2 SDs.

Histograms of IIR-values for the two remaining groups were constructed and all three histograms were tested for skewness. Skewness-values close to zero represent symmetry, negative values represent left-tailed distributions and increasingly positive values represent increasingly right-tailed distributions. A right-tailed distribution would in this case represent increased degrees of fibrosis.

To investigate whether there was possible age-related fibrosis in the healthy control group we divided the group into a younger and older half based on median age and compared the thresholds in these two groups.

Detection of different degrees of native fibrosis

The obtained threshold distinguishing between healthy and fibrotic atrial wall was subsequently applied to the segmentations performed in ADAS ® to detect the degree of native fibrosis in the atrial wall in the three included groups. The degree of fibrosis was calculated as the percentage of pixels in the atrial wall above the set threshold.

Statistics

Continuous variables are presented as mean ± SD or median (interquartile range) and compared with one-way ANOVA/Kruskal–Wallis test. For pairwise comparisons, t-tests were performed. Non-normal distribution variables were logarithmically transformed and tested for normality prior to statistical tests. Inter- and intra-observer variability was performed in a subset of 15 randomly selected participants (five from each group). Intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was evaluated (good correlation was defined as ICC > 0.70). Bland–Altman plots were constructed and visually inspected for bias or proportional error. P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed in SPSS Statistics (version 22, International Business Machines, Armonk, New York, USA).

Results

Table 1 presents clinical baseline data for all included participants. Healthy volunteers and lone AF patients were of similar age (37 SD 6 vs. 39 SD 5 years) and patients in the elderly non-AF group were 76 SD 5 years. None of the healthy volunteers or lone-AF patients had any history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, congestive heart disease or previous stroke, whereas these conditions were present to a varying degree in the elderly group (18–82%).

Image intensity ratio threshold

In total, 308,877 pixel points were registered from healthy controls, 277,666 from lone AF patients and 314,393 from elderly non-AF patients and plotted as histograms (see Fig. 2).

Image intensity (IIR) threshold was extracted from healthy volunteer data (IIR mean + 2 SD) which was 1.21. When separating the healthy controls into an older and a younger fraction according to mean age, the IIR for < 37 (n = 6) and > 37 years (n = 5) were 1.22 ± 0.07 versus 1.21 ± 0.06 (p = 0.92).

The small deviation from the threshold set by Benito et al. [25] (1.20 vs. 1.21) was considered insignificant and hence for further analyses we performed the analyses with the IIR threshold value of 1.20.

Histograms of IIR-values for the three different groups showed skewness values of 0.16 for healthy controls, 0.20 for lone AF patients and 0.70 for elderly non-AF patients, representing increasingly right-tailed distributions.

Detection of different degrees of native fibrosis

Subsequent analyses of the degree of fibrosis in the three groups with the IIR threshold of 1.20 revealed significantly different degrees of fibrosis with a median in healthy volunteers of 2.8% (1.3–8.3), lone-AF patients at 9.0% (3.9–12.0) and reaching the highest median value in elderly non-AF patients at 20.1% (10.2–35.8) (see Table 2). Table 2 shows conventional CMR variables. All measured CMR parameters were statistically similar between the three groups except for IIR-values and the degree of fibrosis.

Inter- and intra-observer agreement was excellent (inter-observer ICC = 0.957 (95% CI 0.880, 0.985) and intra-observer ICC = 0.995 (95% CI (0.986, 0.998). Bland–Altman plots are depicted in Fig. S1. Mean difference for inter-observer agreement was − 1.7 limits of agreement (− 10.25, 6.8) and for intra-observer − 1.0 (− 3.8, 1,7).

Discussion

The present study verifies the use of the image intensity ratio (IIR) threshold value of 1.20 distinguishing healthy from fibrotic atrial myocardium in 1.5T LA LGE scans. This threshold value has previously been established in 3T scans on healthy volunteers [25] but never in 1.5T scans. When using this threshold in analyses of two different patient groups and healthy volunteers we found that young lone-AF patients with paroxysmal AF had increased degrees of atrial fibrosis compared to healthy volunteers in the same age-range. A group of elderly patients with no history of AF but various comorbidities that increases the risk of AF, revealed significantly increased degrees of atrial fibrosis compared to both other groups. This validation means that CMR studies of LA LGE performed on both 3T and 1.5T scanners can be analysed with the same threshold. This is also in line with the results by Chubb et al. [6] that LA LGE results in 1.5T and 3T are comparable.

The IIR analysis method was initially introduced by Khurram et al., who defined two IIR thresholds based on electroanatomic mapping (EAM): One at 0.97 distinguishing healthy myocardium from diffuse fibrosis and the other at 1.61 distinguishing diffuse fibrosis from dense fibrosis [23]. These thresholds were since adjusted by the same group to one IIR threshold of 1.2 based on EAM-data distinguishing fibrotic from healthy atrial wall [29, 30] with reference to a histopathological study by Harrison et al. suggesting new voltage thresholds for EAM [22]. These studies did not include any healthy volunteers and hence only rely on patients with pathologic atrial conditions but agree remarkably with the results from the present study.

CMR determination of LA LGE seems very promising [4, 8, 31, 32]. However, there a differing reports from different centres [5, 33], suggesting that CMR imaging of LA LGE needs to be streamlined with regards to image acquisition and analysis method. More widespread use of LA LGE, in research as well as clinically, depends on optimization of imaging parameters [6, 34] and objectification of imaging analyses [5, 12, 22, 23, 25, 35]. Consensus on imaging parameters and analysis method would make results of clinical studies more robust. Once there is a general agreement on how to perform LA LGE, results from different studies can be pooled and provide better foundation for clinical work [21].

Increased degree of native pre-ablation atrial fibrosis has been associated with age [9, 12, 32, 36], higher CHADS-score [12], hypertension [4, 12], stroke [24, 31], persistent AF [18, 20, 26, 36], re-entrant activity [8] and increased recurrence rates after ablation [4, 8, 10,11,12,13, 37]. The suggested associations between atrial fibrosis and age as well as with various comorbidities is continuously debated, since other studies have not found associations [20, 30, 38, 39].

Our results show that patients with lone AF have higher degrees of atrial fibrosis compared to age-matched healthy volunteers. These patients have no detectable structural heart disease and all included patients had paroxysmal AF, possibly the form with the least electrical and structural remodelling, which was also reflected by similar findings in other CMR parameters. It should especially be noted that atrial dimensions were similar in all three groups. This suggests that AF itself is associated with increased degree of fibrosis independently of structural remodelling, which is also supported by other studies [11, 25, 36, 39]. The question remains though, whether the fibrosis is the cause of AF or vice versa. In an elderly patient group with no history of AF but varying presence of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, congestive heart disease and/or previous stroke we found significantly higher degrees of fibrosis compared to both young groups.

The fibrotic atrial cardiomyopathy (FACM) concept of Kottkamp [38] explains the increased degrees of atrial fibrosis in lone AF patients but although studies are scarce, there is evidence that the degrees of fibrosis increase with age and presence of structural heart disease in patients without AF [36] and it may be that there are several different mechanisms that result in atrial fibrosis. The existence of a FACM syndrome does not rule out that diffuse atrial fibrosis can develop over time and possibly be augmented by various comorbidities. The question remains whether patients with increased degrees of fibrosis of any source are more likely to develop AF compared to patients without fibrosis.

Study limitations

The study is based on a relatively small number of patients and healthy volunteers but nevertheless provides a reproduction of the same IIR threshold value as found by Benito et al. [25]. In general, the IIR method has not been validated against tissue samples but only EAM. While it would have strengthened the results with a further EAM-validation, this would not have been ethically responsible since the study was performed on healthy volunteers.

Fibrosis is a dynamic process stretching from initial inflammation and ultimately potentially development of scar, i.e. stable fibrotic tissue. As in all LGE studies, there is the possibility that visualised LGE in fact reflects early inflammatory processes/oedema in the myocardium and not stable fibrotic tissue [40], hence enhancement may instead be termed suspected fibrosis.

We decided to only test the threshold distinguishing between healthy and fibrotic atrial wall since this separation is clinically relevant and we have found no studies suggesting further value of two thresholds.

The thickness of the atrial wall is close to the resolution of CMR and hence especially for thin in-plane structures the 3D-acquisition can provide low accuracy and some degree of partial volume effects may be unavoidable.

While some studies find no correlation between age and increased fibrosis [8, 20, 26, 38] and others do [9, 12], we decided to set an upper age-limit at 45 years to avoid possible age-related fibrosis in healthy volunteers.

With regards, to the elderly non-AF population, there is the possibility that they have experienced asymptomatic AF episodes.

Conclusion

In 1.5T LA LGE scans on healthy volunteers we found an IIR threshold of 1.21 for healthy versus fibrotic tissue which is similar to the previously found threshold of 1.20 in 3T scans. The IIR threshold between healthy and fibrotic atrial myocardium of 1.2 can thus be used for both field strengths.

Using the IIR threshold of 1.20, we found increased degrees of left atrial fibrosis in patients with lone paroxysmal AF compared to healthy controls in the same age-range. Elderly patients with no known history of AF but known diabetes mellitus, hypertension, congestive heart disease and/or previous stroke had significantly higher degrees of left atrial fibrosis than both groups of younger individuals.

References

Lee D, Markl M, Dall’Armellina E, Han Y, Kozerke S, Kuehne T et al (2018) The growth and evolution of cardiovascular magnetic resonance: a 20-year history of the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance (SCMR) annual scientific sessions. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 20(8):1–11

Kim RJ, Fieno DS, Parrish TB, Harris K, Chen EL, Simonetti O et al (1999) Relationship of MRI delayed contrast enhancement to irreversible injury, infarct age, and contractile function. Circulation 100(19):1992–2002

Peters DC, Wylie JV, Hauser TH, Kissinger KV, Botnar RM, Essebag V et al (2007) Detection of pulmonary vein and left atrial scar after catheter ablation with three-dimensional navigator-gated delayed enhancement MR imaging: initial experience. Radiology 243(3):690–695

Marrouche NF, Wilber D, Hindricks G, Jais P, Akoum N, Marchlinski F et al (2014) Association of atrial tissue fibrosis identified by delayed enhancement MRI and atrial fibrillation catheter ablation: the DECAAF study. JAMA: J Am Med Assoc 311(5):498–506

Sramko M, Peichl P, Wichterle D, Tintera J, Weichet J, Maxian R et al (2015) Clinical value of assessment of left atrial late gadolinium enhancement in patients undergoing ablation of atrial fibrillation. Int J Cardiol 179:351–357

Chubb H, Karim R, Roujol S, Nunez M, Williams SE, Whitaker J et al (2018) The reproducibility of late gadolinium enhanced cardiac magnetic resonance imaging of post-ablation atrial scar: a cross-over study. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 20:1–15

Sohns C, Lemes C, Metzner A, Fink T, Chmelevsky M, Maurer T et al (2017) First-in-man analysis of the relationship between electrical rotors from noninvasive panoramic mapping and atrial fibrosis from magnetic resonance imaging in patients with persistent atrial fibrillation. Circ Arrhythmia Electrophysiol 10:1–12

Cochet H, Dubois R, Yamashita S, Al Jefairi N, Berte B, Sellal JM et al (2018) Relationship between fibrosis detected on late gadolinium-enhanced cardiac magnetic resonance and re-entrant activity assessed with electrocardiographic imaging in human persistent atrial fibrillation. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 4(1):17–29

Benito EM, Cabanelas N, Nuñez-Garcia M, Alarcón F, Figueras I, Ventura RM, Soto-Iglesias D et al (2018) Preferential regional distribution of atrial fibrosis in posterior wall around left inferior pulmonary vein as identified by late gadolinium enhancement cardiac magnetic resonance in patients with atrial fibrillation. Europace 20(12):1959–1965

McGann CJ, Kholmovski EG, Oakes RS, Blauer JJE, Daccarett M, Segerson N et al (2008) New magnetic resonance imaging-based method for defining the extent of left atrial wall injury after the ablation of atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol 52(15):1263–1271

Oakes RS, Badger TJ, Kholmovski EG, Akoum N, Burgon NS, Fish EN et al (2009) Detection and quantification of left atrial structural remodeling with delayed-enhancement magnetic resonance imaging in patients with atrial fibrillation. Circulation 119:1758–1767

Malcolme-Lawes LC, Juli C, Karim R, Bai W, Quest R, Lim PB et al (2013) Automated analysis of atrial late gadolinium enhancement imaging that correlates with endocardial voltage and clinical outcomes: a 2-center study. Heart Rhythm 10:1184–1189

McGann C, Akoum N, Patel A, Kholmovski E, Revelo P, Damal K et al (2014) Atrial fibrillation ablation outcome is predicted by left atrial remodeling on MRI. Circ Arrhythmia Electrophysiol 7:23–30

Bisbal F, Guiu E, Cabanas-Grandío P, Berruezo A, Prat-Gonzalez S, Vidal B et al (2014) CMR-guided approach to localize and ablate gaps in repeat AF ablation procedure. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 7(7):653–663

Badger TJ, Daccarett M, Akoum NW, Adjei-Poku YA, Burgon NS, Haslam TS et al (2010) Evaluation of left atrial lesions after initial and repeat atrial fibrillation ablation; lessons learned from delayed-enhancement MRI in repeat ablation procedures. Circ Arrhythmia Electrophysiol 3:249–259

Spragg DD, Khurram I, Zimmerman SL, Yarmohammadi H, Barcelon B, Needleman M et al (2012) Initial experience with magnetic resonance imaging of atrial scar and co-registration with electroanatomic voltage mapping during atrial fibrillation: success and limitations. Heart Rhythm 9:2003–2009

Harrison JL, Sohns C, Linton NW, Karim R, Williams SE, Rhode KS et al (2015) Repeat left atrial catheter ablation. Circ Arrhythmia Electrophysiol 8:270–278

den Uijl DW, Cabanelas N, Benito EM, Figueras R, Alarcón F, Borràs R et al (2018) Impact of left atrial volume, sphericity, and fibrosis on the outcome of catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 29:740–746

Hunter RJ, Jones DA, Boubertakh R, Malcolme-Lawes LC, Kanagaratnam P, Juli CF et al (2013) Diagnostic accuracy of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in the detection and characterization of left atrial catheter ablation lesions: a multicenter experience. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 24:396–403

Akoum N, Daccarett M, McGann C, Segerson N, Vergara G, Kuppahally S et al (2011) Atrial fibrosis helps select the appropriate patient and strategy in catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation: a DE-MRI guided approach. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 22(1):16–22

Pontecorboli G, Ventura RMFI, Carlosena A, Benito E, Prat-Gonzales S, Padeletti L et al (2017) Use of delayed-enhancement magnetic resonance imaging for fibrosis detection in the atria: a review. Europace. 19:180–189

Harrison JL, Jensen HK, Peel SA, Chiribiri A, Grondal AK, Bloch LO et al (2014) Cardiac magnetic resonance and electroanatomical mapping of acute and chronic atrial ablation injury: a histological validation study. Eur Heart J 35:1486–1495

Khurram IM, Beinart R, Zipunnikov V, Dewire J, Yarmohammadi H, Sasaki T et al (2014) Magnetic resonance image intensity ratio, a normalized measure to enable interpatient comparability of left atrial fibrosis. Heart Rhythm 11:85–92

Daccarett M, Badger TJ, Akoum N, Burgon NS, Mahnkopf C, Vergara G et al (2011) Association of left atrial fibrosis detected by delayed-enhancement magnetic resonance imaging and the risk of stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol 57(7):831–838

Benito EM, Carlosena-Remirez A, Guasch E, Prat-González S, Perea RJ, Figueras R et al (2017) Left atrial fibrosis quantification by late gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance: a new method to standardize the thresholds for reproducibility. Europace 19(8):1272–1279

Dewire J, Khurram IM, Pashakhanloo F, Spragg D, Marine JE, Berger RD et al (2014) The association of pre-existing left atrial fibrosis with clinical variables in patients referred for catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation. Clin Med Insights Cardiol 8(S1):25–30

Habibi M, Lima JAC, Khurram IM, Zimmerman SL, Zipunnikov V, Fukumoto K et al (2015) Association of left atrial function and left atrial enhancement in patients with atrial fibrillation. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 8:1–10

Klumpp B, Fenchel M, Hoevelborn T, Helber U, Scheule A, Claussen C et al (2006) Assessment of myocardial viability using delayed enhancement magnetic resonance imaging at 3.0 Tesla. Invest Radiol 41(9):661–667

Chrispin J, Gucuk Ipek E, Zahid S, Prakosa A, Habibi M, Spragg D et al (2016) Lack of regional association between atrial late gadolinium enhancement on cardiac magnetic resonance and atrial fibrillation rotors. Heart Rhythm 13(3):654–660

Chrispin J, Ipek EG, Habibi M, Yang E, Spragg D, Marine JE et al (2017) Clinical predictors of cardiac magnetic resonance late gadolinium enhancement in patients with atrial fibrillation. Europace 19:371–377

Fonseca AC, Alves P, Inácio N, Marto JP, Viana-Baptista M, Pinho-E-Melo T et al (2018) Patients with undetermined stroke have increased atrial fibrosis: a cardiac magnetic resonance imaging study. Stroke 49:734–737

Azadani PN, King JB, Kheirkhahan M, Chang L, Marrouche NF, Wilson BD (2017) Left atrial fibrosis is associated with new-onset heart failure in patients with atrial fibrillation. Int J Cardiol 2017(248):161–165

Bois JP, Glockner J, Young PM, Foley TA, Sheldon S, Newman DB et al (2017) Low incidence of left atrial delayed enhancement with MRI in patients with AF: a single-centre experience. Open Heart 4:1–5

Chubb H, Aziz S, Karim R, Sohns C, Razeghi O, Williams SE et al (2018) Optimization of late gadolinium enhancement cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging of post-ablation atrial scar: a cross-over study. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 20(1):1–17

Karim R, Housden J, Balasubramaniam M, Chen Z, Perry D, Uddin A et al (2013) Evaluation of current algorithms for segmentation of scar tissue from late Gadolinium enhancement cardiovascular magnetic resonance of the left atrium: an open-access grand challenge. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 15(105):1–17

Cochet H, Mouries A, Nivet H, Sacher F, Derval N, Denis A et al (2015) Age, atrial fibrillation, and structural heart disease are the main determinants of left atrial fibrosis detected by delayed-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging in a general cardiology population. J Cardiovas Electrophysiol 26(5):484–492

Khurram IM, Habibi M, Gucuk Ipek E, Chrispin J, Yang E, Fukumoto K et al (2016) Left atrial LGE and arrhythmia recurrence following pulmonary vein isolation for paroxysmal and persistent AF. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 9(2):142–148

Kottkamp H (2013) Human atrial fibrillation substrate: towards a specific fibrotic atrial cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J 34:2731–2738

Mahnkopf C, Badger TJ, Burgon NS, Daccarett M, Haslam TS, Badger CT et al (2010) Evaluation of the left atrial substrate in patients with lone atrial fibrillation using delayed-enhanced MRI: implications for disease progression and response to catheter ablation. Heart Rhythm 7:1475–1481

Mewton N, Liu CY, Croisille P, Bluemke D, Lima JAC (2011) Assessment of myocardial fibrosis with cardiovascular magnetic resonance. J Am Coll Cardiol 57(8):891–903

Funding

The study was funded by research grants from the Arvid Nilsson Foundation. LB was funded through a research grant from the Innovation Fund, University of Copenhagen and The Oticon Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

LM received unrestricted research and fellowship grants from Abbott, Biosense Webster, Boston Scientific and Medtronic. Stock holder for Galgo Medical; JHS received unrestricted research grant from Medtronic and Gilead; Member of Medtronic advisory board and receives speaker fee from Medtronic. The other authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The study protocol conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki as reflected in a priori approval by the local ethics committee of the Capital Region of Denmark (Protocol Number H-1-2011-044 and H-4-2013-025).

Informed consent

All included participants were scanned for research purposes and provided written informed consent prior to inclusion.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Bertelsen, L., Alarcón, F., Andreasen, L. et al. Verification of threshold for image intensity ratio analyses of late gadolinium enhancement magnetic resonance imaging of left atrial fibrosis in 1.5T scans. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 36, 513–520 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10554-019-01728-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10554-019-01728-0