Abstract

Deviant workplace behaviors (DWB) cause enormous costs to organizations, sparking considerable interest among researchers and practitioners to identify factors that may prevent such behavior. Drawing on the theory of moral development, we examine the role of ethics-oriented human resource management (HRM) systems in mitigating DWB, as well as mechanisms that may mediate and moderate this relationship. Based on 232 employee-supervisor matched responses generated through a multi-source and multi-wave survey of 84 small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in Pakistan, our multilevel analysis found that ethics-oriented HRM systems relate negatively to employee DWB via the mediation of perceptual and reflective moral attentiveness. This indirect relationship is further moderated by two societal-inequality induced factors – employee gender and income level – such that the indirect effects of ethics-oriented HRM systems on DWB through perceptual and reflective moral attentiveness are stronger among women and lower-income employees.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Employees’ deviant workplace behavior (DWB), defined as “voluntary behavior that violates organizational norms and thereby threatens the well-being of the organization, its members, or both” (Robinson & Bennett, 1995, p. 556) is a serious issue in organizations. Employees may engage in DWB intentionally, for instance to serve self-interest or to retaliate against mistreatment and injustice (Park et al., 2019; Scherer et al., 2001), or unintentionally, such as when they fail to identify moral situations and ethically questionable actions (Shafer, 2008; Treviño et al., 2006). At the individual level, DWB can be a function of personality (Ménard et al., 2011), attitude (Bolin & Heatherly, 2001), identification (Chen et al., 2016), or psychological entitlement (Lee et al., 2019). At the organizational level, DWB may be influenced by (un)ethical leadership (Miao et al., 2020), ethical climate (Hsieh & Wang, 2016), or the employee-organization relationship (Chiu & Peng, 2008).

While much is known about the individual and organization-level antecedents of DWB, it remains an alarming issue in the workplace (Di Stefano et al., 2019; Hsieh & Wang, 2016), and therefore how organizations can mitigate such behaviors is a topic of concern among organizational scholars (Di Stefano et al., 2019; Griffin & Lopez, 2005; Huang & Paterson, 2017; Larkin et al., 2021). On the one hand, strategic human resource management (HRM) scholars suggest a role for HRM systems, defined as bundles of HRM practices that aim to achieve specific organizational outcomes (Arthur, 2011; Götz et al., 2019; Kehoe & Wright, 2013; Xu & Lv, 2018). On the other hand, behavioral ethics scholars stress the need to address the moral foundations of individual employees (Egorov et al., 2019; McMahon & Good, 2016). Since both streams hold merits, scholars have started adopting an ethics lens on the role of HRM systems in achieving ethical outcomes (Guerci et al., 2015; Valentine et al., 2014; Wurthmann, 2013).

Though this literature has greatly enhanced our understanding of the relationship between HRM systems, moral development, and (un)ethical behaviors, it faces important limitations. First, studies examining HRM systems-DWB relationships have typically focused on performance-oriented HRM systems rather than HRM systems targeted at behavioral outcomes (Jackson et al., 2014; Jiang et al., 2012). Performance-oriented HRM systems may in fact stimulate DWB because of employees’ high job demands and unilateral focus on performance (Zhang et al., 2022) as well as a felt obligation to contribute to the organization at all costs (Xu & Lv, 2018). This creates a need to conceptualize ethics-based HRM systems to reduce DWB. Second, while scholars have recently shown that ethics-based HRM systems may improve ethical climate (Guerci et al., 2015, 2017), the findings on the relationship between ethical climate and unethical behaviors such as DWB remain mixed (Atabay et al., 2015; Peterson, 2002; Shafer, 2008). Third, the extant literature tends to rely on social exchange or social learning theories (Bandura, 1991; Blau, 1964), by which, e.g., the transparency, fairness, or well-being concern of HRM practices mitigate DWB through a modeling effect (Gould-Williams, 2007; Manroop et al., 2014). However, these perspectives are incomplete, given that employees may also commit DWB unintentionally (Boatright, 2013; Hong, 2019; Kidwell & Kochanowski, 2005).

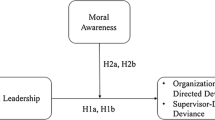

To address these issues, we draw from the theory of moral development (Kohlberg, 1976, 1981) to investigate how strategically targeted ethics-oriented HRM systems, defined as “set[s] of HRM practices aimed at developing organizational ethics” (Guerci et al., 2015, p. 332), exert cross-level influences on employee DWB through the development of employees’ moral attentiveness. Moral attentiveness, or the extent to which a person “perceives and considers morality and moral elements in his or her experiences” (Reynolds, 2008, p. 1028), consists of two dimensions: perceptual moral attentiveness and reflective moral attentiveness. Whereas perceptual moral attentiveness refers to how incoming information is colored by the individual through a moral lens, reflective moral attentiveness captures how information can be regularly considered and reconsidered through that lens (Reynolds, 2008). Moral attentiveness thus represents an important underlying moral capacity of an individual to interpret and handle moral incidents, and can be understood as a key component of employees’ self-regulatory moral capacity (Chung & Hsu, 2017; Hannah et al., 2011). Accordingly, we argue that ethics-oriented HRM systems mitigate DWB by increasing the likelihood that employees will perceive moral aspects in everyday work experiences and use morality as a cognitive foundation to reflect upon these experiences (van Gils et al., 2015).

Additionally, we expand on the theory of moral development to suggest that employees’ gender and income level differences may moderate the effect of ethics-oriented HRM systems on DWB through moral attentiveness. Although research notes significant disparity in employees’ ethics, morals, and responses to HRM systems due to differences in gender and income levels (Leana & Meuris, 2015; Shin et al., 2020; Siu & Lam, 2009; Smith & Oakley, 1997), it is unknown how such contextual factors play into the relationship between ethics-oriented HRM systems, moral attentiveness, and DWB. We theorize that individuals’ gender and income levels affect their moral ideology (Sullivan, 1977) and thus the extent to which they attend to moral cues, including those embedded in organizational interventions. Accordingly, we theorize that gender and income level moderate the relationships between ethics-oriented HRM systems, moral attentiveness, and DWB.

To test our hypotheses, we employed a multi-source and multi-wave design, with ethics-oriented HRM systems measured by employees at time 1, moral attentiveness reported by employees at time 2 (after 12 months), and DWB rated by supervisors at time 3 (6 months after time 2). As scholars typically study the effect of HRM systems on (un)ethical behaviors through a cross-sectional design, the cross-level effects of ethics-oriented HRM systems that occur on DWB over time, as well as the process through which this occurs, remain unknown. Our research design to collect data from multiple sources with temporal separation across three time points is considered appropriate to mitigate the risk of common method variance (McClean & Collins, 2019; Podsakoff et al., 2012). Our final sample across the three waves comprised 232 individual responses from 84 small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in Pakistan. Our multilevel analysis found that ethics-oriented HRM systems lead to lower levels of DWB; this relationship is mediated by perceptual and reflective moral attentiveness; and the relationship between ethics-oriented HRM systems and moral attentiveness is stronger for women and low-income employees.

In so doing, our study makes three contributions to the research on strategic HRM and (un)ethical workplace behaviors. First, we explicate the role of strategically targeted ethics-oriented HRM systems as a macro-level inhibitor of DWB. Instead of focusing on general contextual outcomes such as ethical climate, whose relationships to DWB are unclear, we engage in a cross-level examination of ethics-oriented HRM systems on individual DWB outcomes, thereby responding to recent calls for a more holistic and multilevel conceptualization of organizational practices to control DWB (Mackey et al., 2021). Second, we unpack the black box of ethics-oriented HRM systems by exploring the role of individuals’ self-regulatory moral mechanisms, which have been found to be a strong predictor of (un)ethical behaviors (Reynolds, 2008; van Gils et al., 2015). In so doing, we respond to the call for the exploration of more paths through which organization-level factors influence employee (un)ethical behavior (Reynolds, 2008). Third, by examining the roles of employee gender and income level in moderating the effect of ethics-oriented HRM systems on employee moral attentiveness and subsequently DWB, we contribute to the theory of moral development by identifying individual demographics as boundary conditions of the effectiveness of moral development interventions such as ethics-oriented HRM systems.

Theoretical Framework and Hypothesis Development

Deviant Workplace Behaviors (DWB)

Workplace deviance is an important ethical issue in organizations (Mackey et al., 2021). DWB include a set of behaviors, such as employee theft, harassment, or lying, that go against workplace rules and regulations and bring harm to both the organization and its members (Robinson & Bennett, 1995). Employees engage in DWB due to different reasons, including self-interest, retaliation to injustice and mistreatment, modeling influence of unethical co-workers and leadership, or failure to identify moral situations and ethically questionable actions (Mackey et al., 2021; Shafer, 2008).

Bing and coauthors (2007) assert that implicit and explicit biases particularly contribute to workplace deviance by influencing how employees perceive and interact with others in the workplace. Implicit bias refers to unconscious attitudes or stereotypes that affect our understanding, actions, and decisions without our awareness. Explicit bias, on the other hand, refers to conscious and deliberate attitudes or beliefs that are expressed openly. For example, if an employee holds an implicit bias against supervisors or colleagues based on race, gender, age, or religion, s/he may feel justified in engaging in ignoring, bullying, harassing, or spreading rumors about them. Similarly, if an employee holds an explicit bias against the company or certain individuals within it, s/he may be more likely to engage in theft, fraud, and sabotaging as a form of retaliation.

Bing et al. (2007) emphasize the importance of addressing implicit and explicit biases to reduce deviance and promote a more equitable and inclusive workplace. They suggest that organizations can use formal interventions to increase employees’ awareness of and exposure to implicit biases, stigmatized groups, and the discrepancy between implicit and explicit attitudes. Educating individuals, through training, to understand the limitations of their own explicit and implicit biases is an important aspect of critical self-reflection and resultant decision making and behaviors within the bounds of ethical and moral responsibilities to colleagues and the organization (Davison et al., 2020; Dixon et al., 2012; Michel et al., 2014).

The theory of moral development highlights the moral cognitive foundations of DWB. Based on this theory, DWB is not a primitive reaction to one’s circumstances, but rather can be attributed to an employee’s moral forethought (Reynolds, 2008) and how much attention s/he pays to the moral implications of routine decisions and behaviors (Reynolds et al., 2012). A moral development lens suggests that formal organizational practices may develop employees’ moral trajectories and thereby generate a more nuanced cognizance of DWB, its determinants, and underlying reasoning (Henle et al., 2005; Treviño et al., 2006).

Ethics-Oriented HRM Systems

The concept of ethics-oriented HRM systems is based on the notion of a strategically targeted HRM system. Unlike performance-oriented HRM systems that focus on general performance outcomes, a strategically targeted HRM system is an intentionally designed bundle of HRM practices that aims to achieve targeted organizational outcomes (Jackson et al., 2014; Kehoe & Wright, 2013) such as creativity (Martinaityte et al., 2019), safety (Zacharatos et al., 2005), service quality (Hong et al., 2017), or corporate social responsibility (Shen & Benson, 2016). Corporate scandals, tarnished reputations of organizations, and recognition of ethics as an important dimension of organizational performance (Huang & Paterson, 2017) have led strategic HRM scholars to conceptualize ethics-oriented HRM systems which Guerci et al., (2015, p. 332; 2017, p. 66) defined as “set[s] of HRM practices aimed at developing organizational ethics.”

This conceptualization of ethics-oriented HRM systems is aligned with moral development theory as it focuses on the development of an ethically competent workforce through its ethical ability enhancing, ethical motivation enhancing, and ethical opportunity enhancing practices (Guerci et al., 2017). Specifically, selection, training, performance appraisal, rewards/sanctions, job design, and participation practices help organizations to acquire, develop, motivate, and retain an ethical workforce attentive to the complexities of ethical dilemmas and implications of decisions and actions. Given this, we argue that an ethics-oriented HRM system, through its integrated bundle of ethics-oriented HRM practices and an explicit focus on ethics and morality of the workforce, has the potential to help the organization deal with unethical behaviors (Valentine et al., 2019).

Ethics-Oriented HRM Systems and DWB

From an HRM perspective, DWB can be mitigated through the organization’s formal ethics-oriented interventions (Ferris et al., 2012; Treviño & Nelson, 2021). First, ethics-oriented HRM systems can mitigate DWB by cultivating an ethical workforce, for example through ethics-based selection and training (Hannah et al., 2011; McMahon & Good, 2016). Victor and Cullen (1987) assert that employees’ ethics result partially from their own prior moral characters, and partially from the organizational values system when they learn “the right way” of behaving in the organization (Victor & Cullen, 1987, p. 51). A systematic screening of applicants who share the same ethical values of the organization creates a good match between the organization and its members (Guerci et al., 2015). Ethics-based training programs can inhibit DWB by providing employees with moral cognitive resources to interpret ethically ambiguous events and construe decisions and behaviors with greater moral inputs (Hannah et al., 2011; Valentine et al., 2019). These interventions can inhibit DWB by developing employees’ ability to challenge their moral judgments, stimulate moral curiosity, explore and adopt different moral schemas to think about the morality of decisions, and consciously influence moral sense, principles, and values of others (Egorov et al., 2019; Weaver et al., 2014).

Second, the development of ethical behaviors also depends on the motivation to handle moral incidents with moral input (Hannah et al., 2011). Ethical motivation entails the weight assigned to specific moral values over other values (McMahon & Good, 2016). An ethics-oriented HRM system may deploy value-oriented rewards such as pay, bonuses, and favorable appraisals for ethical behaviors, and/or compliance-oriented costs such as punishment and sanctions for deviant behaviors (Manroop et al., 2014; Tay et al., 2017), to enhance employees’ moral ownership and reduce their motivation to exhibit deviant behaviors (Valentine et al., 2019). As a result, employees develop a heightened awareness of the moral obligations and performance implications of their (im)moral decisions and actions, and thus are more likely to comply with the organization’s ethical values and standards via self-regulation (Jennings et al., 2015).

Third, an ethics-oriented HRM system develops a conducive environment that enables employees to exhibit ethical and avoid unethical behaviors (Guerci et al., 2015). It provides employees with autonomy, encouragement, and career assurance to come up with ethical solutions independently, act in ethical ways, and report or stop unethical conduct by others. Practices such as whistle-blowing and speak-up policies help promote ethically-oriented procedures such as transparent and fair career paths (Bureau et al., 2018). Formal mechanisms to monitor and report (un)ethical behaviors also provide organization members with an opportunity to refine their moral sense and reflect on their experiences (Sadler-Smith, 2012). Taken together, we argue that the ethics-oriented HRM system, as an aggregated construct, has the potential to inhibit DWB through its explicit focus on ethics and morality of employees (Valentine et al., 2014), and hypothesize as follows:

Hypothesis 1

An ethics-oriented HRM system will be negatively related to employee DWB.

The mediating Role of Moral Attentiveness

We further argue that ethics-oriented HRM systems will be related to employee DWB through their effects on employee moral attentiveness, which is “the extent to which an individual chronically perceives and considers morality and moral elements in his or her experiences” (Reynolds, 2008, p. 1028). Whereas some scholars consider moral attentiveness a stable and dispositional construct (van Gils et al., 2015), much literature on moral cognition development (Chung & Hsu, 2017; Hannah et al., 2011; Kohlberg, 1976, 1981; Wurthmann, 2013) suggests that moral attentiveness is a malleable and scalable individual capacity that can be developed through moral interventions and other opportunities to practice moral reasoning, such as training, ethical leadership development programs, and rewards and punishments (Jennings et al., 2015; Miao et al., 2020; Moore et al., 2019; Zhao & Zhou, 2021).

Specifically, moral attentiveness has two dimensions: perceptual moral attentiveness, “the recognition of moral aspects in everyday experiences,” and reflective moral attentiveness, “the extent to which the individual regularly considers moral matters” (van Gils et al., 2015, p. 192). Individuals who are perceptually morally attentive are more likely to notice moral content in an event or situation. In this regard, their cognitive frameworks contain an increased tendency toward the screening of situations and behaviors for their ethical aspects (Reynolds, 2008). Reflective moral attentiveness, in contrast, is related to persistent attention to the moral content in one’s actions and decisions, which may direct an individual towards an automatic or reflexive moral course of action. In this perspective, issues are not objectively moral but rather constructed by individuals as moral (Reynolds, 2006).

Moral development theory explains that upgrading individuals’ moral cognitive resources requires targeted and consistent developmental interventions to cultivate their moral cognitive frameworks (Egorov et al., 2019; McMahon & Good, 2016). Ethics-oriented HRM systems first communicate, monitor, and reward ethical expectations and prime employees to attend to ethical issues. For example, selecting employees who share organizational ethical values followed by ethics-enhancing training programs sharpen employees’ perceptual and reflective capacity to identify and apply moral content in their day-to-day decisions and behaviors (Boatright, 2013; Wurthmann, 2013). Similarly, strengthening the ethical effort-performance and ethical performance-reward/sanction links can make employees perceptually and reflectively more attentive to moral aspects and adopt ethical thinking and behaviors (Hannah et al., 2011; McMahon & Good, 2016). Lastly, practices such as suggestion and feedback and participation in moral decision-making create opportunities for employees to strengthen their moral schemas, sensemaking, and reflective attitude towards day-to-day decisions and actions.

At the same time, in ethically dubious situations that pose employees with a dilemma, their perceptual moral attentiveness helps them to perceive and recognize moral issues or moral content in the situation, and reflective moral attentiveness enables them to reflect on their own moral values, principles, and beliefs to consider ethical dilemma more deeply and deliberately to engage in moral reasoning and analysis of the ethical implications of their decisions and behaviors (Reynolds, 2008). Ethics-oriented HRM systems develop the moral capability and motivation of employees to identify moral incidents and construe perceptions and behaviors driven by core moral values of the organization (Dawson, 2018; Wurthmann, 2013). For example, organizations can select and train employees with critical thinking ability to reflect on the ethical implications of decisions and behaviors. Performance appraisal and rewards tied to the successful execution of moral decisions help boost employees’ motivation to engage in moral reasoning. By consistently engaging employees in morality-focused discussions and stressing the need for them to engage in moral reflection in every decision, ethics-oriented HRM systems, over time, make their ethical cognitive process automatic and chronic (Nishii & Paluch, 2018; Reynolds, 2006; Weaver et al., 2014).

Perceptual and reflective moral attentiveness are in turn associated with individuals’ (un)ethical choices and behaviors (Jennings et al., 2015; Reynolds et al., 2012; Zhu et al., 2016). One of the main catalysts of individuals’ (un)ethical behaviors is their cognitive ability and propensity to recognize the moral content inherent in a given situation (Resick et al., 2013). The notion of moral attentiveness as a cognitive ability is supported by research showing a positive association between business ethics education and perceptual moral attentiveness (Wurthmann, 2013). In turn, reflective moral attentiveness has been shown to reduce individuals’ unethical decision making, such as bribery for the benefit of their organization (Culiberg & Mihelič, 2016). These findings suggest that moral attentiveness may mediate between organizations’ ethical interventions and employees’ ethical behaviors. For instance, Wurthmann (2013) found that reflective moral attentiveness mediated the effects of business ethics education on the extent to which individuals perceived that ethics and social responsibility are important. Similarly, Miao et al. (2020) found that reflective moral attentiveness mediated the relationship between ethical leadership and unethical pro-organization behaviors. Therefore, we expect:

Hypothesis 2

Employee a) perceptual moral attentiveness and b) reflective moral attentiveness mediate the relationship between ethics-oriented HRM system and employee DWB.

The Moderating Role of Gender and Income

Besides calling for a better understanding of the mediating process between ethical practices and DWB, researchers have highlighted a need to identify boundary conditions that influence the efficacy of targeted HRM systems in shaping moral processes and behavioral outcomes (Jackson et al., 2014). Because moral attentiveness pertains to an individual’s moral development, the effect of ethics-oriented HRM systems on employee moral attentiveness and DWB will depend on how well employees interpret and internalize the HRM systems’ ethics-oriented content (Hu & Jiang, 2018). Gender and income are considered two individual demographic factors that strongly predict individual ethical and moral differences (Kacmar et al., 2011; Leana & Meuris, 2015; Lee & Kray, 2021). Therefore, based on moral development theory, we expect them to moderate the effectiveness of ethics-oriented HRM systems in garnering moral outcomes.

The literature on gender differences suggests that due to their societal heritage, women have different ethical tendencies and behaviors than their male counterparts (De Cristofaro et al., 2021; Leana & Meuris, 2015). As argued by Flanagan and Jackson (1987, p. 623), “men, more often than women, conceive of morality as substantively constituted by obligations and rights and as procedurally constituted by the demands of fairness and impartiality, while women, more often than men, see moral requirements as emerging from the particular needs of others in the context of particular relationships.” Further, gender role socialization leads to an expectation of women to be wholesome, respectful, conforming, and perceptive (Heilman, 2012). This suggests that women and men are differently aligned with ethical reasoning, the integrity of employee relations, ethical standards for others, sharing information, and the tendency to report (un)ethical behaviors (Reynolds, 2008; Ritter, 2006; Smith & Oakley, 1997). Indeed, women and men often employ different ethical reasoning schemas, exhibit differences in personal integrity, evaluate unethical practice differently, and hold others to different ethical standards (Smith & Oakley, 1997; Wiley, 1998).

Considering this, we argue that women may be more receptive to the effects of ethics-oriented HRM systems on DWB through moral attentiveness. First, women tend to conceptualize ethics as “care” in connection to others, which makes women’s ethical reasoning more contextual and situational than that of men (Gilligan, 1982). This contextual orientation allows women to better perceive and decode the ethics-oriented practices and policies inherent in an ethics-oriented HRM system (an organizational context). Second, extending the ethics of “care,” the theory of virtue ethics underscores the rationality of women to pursue “internal goods” that benefit others in the community, as opposed to “external goods”' that pertain to individuals’ possessions (MacIntyre, 1984). This internal-good based rationality enables women to better interpret and internalize the embedded organizational values in the ethics-oriented HRM system that expect and encourage ethical behaviors of employees (Ritter, 2006).

Further, women, given their greater tendency to conform, are more likely to perceive ethics-oriented HRM practices such as ethics-based performance management, rewards, and sanctions as more salient, vivid, and accessible than men (Reynolds, 2008). Studies have found that women are more receptive to ethics-oriented developmental interventions such that ethical training has no effect on male students and a significant effect on female students (Ritter, 2006). As such, when exposed to an ethics-oriented HRM system, female employees will develop greater moral attentiveness to actively screen morally salient and vivid stimuli in daily events, as well as to proactively construct moral reasoning and form intuitive moral decision making. Accordingly, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 3

Employee gender moderates the effect of an ethics-oriented HRM system on employee a) perceptual moral attentiveness and b) reflective moral attentiveness, which are in turn negatively related to DWB, such that the indirect effect will be stronger for women than for men.

We also theorize a moderating role for employee income. Income disparities prevail globally at both the societal and organizational levels, a fact which concerns both scholars and practitioners due to its moral and behavioral implications (Trevor et al., 2012). Behavioral ethics scholars suggest that the dispersion of income can influence individual and collective behavior and attitudes (Leana & Meuris, 2015), such as heightened workplace deviance and turnover (Huiras et al., 2000). Particularly, exposure to and desire for wealth heightens individuals’ feelings of envy and unethical tendencies (Gino & Pierce, 2009; Moore & Gino, 2015). Due to their different experience in inequality and ethical dilemmas, lower-income individuals may possess a different understanding of what constitutes (im)moral behavior, exhibit different patterns of social interaction, perceive different costs and benefits of undertaking (im)moral behavior, and make different social comparisons, than higher-income individuals do (Clark & Senik, 2010).

Given that individuals of different income levels exhibit different moral values and behaviors at the workplace (Siu & Lam, 2009), income level may influence the tendency of individuals to pay attention to the signals sent by ethics-oriented HRM systems for cultivating individuals’ moral capacity. First, due to their constrained financial status, the stronger association of ethical behaviors with performance appraisal, compensation, and sanctions embedded in the ethics-oriented HRM systems will motivate lower-income individuals more than their higher-income counterparts to adhere to high ethical standards and overcome their tendency to conduct unethical behaviors. Second, self-determination theory suggests that extrinsic motivation of high-income individuals (whose performance is often tied to a great disparity in income) can lead to reduced intrinsic motivation and voluntary efforts towards moral development (Deci & Ryan, 1985). On the contrary, lower-income employees who are not constantly incentivized to pursue monetary gains on their job may be more intrinsically motivated to receive ethical training and development to augment their ability to screen for and recognize moral issues and responsibilities, as well as their willingness to weigh the moral implications of actions (Ritter, 2006). Indeed, Frey and Oberholzer-Gee (1997) found that monetary incentives undermined individuals’ sense of civic virtues. As such, ethics-oriented HRM systems may more effectively improve lower-income individuals’ moral attentiveness to discern and analyze moral implications of different decisions, and, in so doing, have a greater effect on their DWB than they do for higher-income individuals. We hypothesize as follows:

Hypothesis 4

Employee income level moderates the effect of ethics-oriented HRM system on employee a) perceptual moral attentiveness and b) reflective moral attentiveness, which are in turn negatively related to DWB, such that the indirect effect will be stronger for lower-income rather than higher-income employees.

Data and Method

To analyze these relationships, we employ a multi-source and multi-wave design (Mackey et al., 2021; Treviño et al., 2006) among employees of small- and medium enterprises (SMEs) in Pakistan. Ethics-oriented HRM systems were measured by employees at time 1, moral attentiveness reported by employees at time 2 (after 12 months), and DWB rated by supervisors at time 3 (6 months after time 2). We incorporated these lags because, as George and Jones asserted (2000, p. 670), behavioral effects do not occur instantly as a result of targeted policy interventions; instead, “some level of time aggregation is necessarily involved.” There are several studies that have employed a time-lag of three months (e.g. Hu et al., 2015), six months (Yang et al., 2021), and one year (Collins & Clark, 2003) to collect data to test the effect of HRM practices on outcome variables. McClean and Collins (2019) in their recent study employed a time lag of approximately 1 year to measure the effect of HRM practices on employees’ performance and behaviors, and found this time lag more appropriate to understand causality and eliminate issues associated with collecting data at the same point in time (Gerhart et al., 2000).

Additionally, we formed a panel consisting of two academics (with a Ph.D. degree and consultancy/training experience with SMEs), two industry experts (one from the Chamber of Commerce, and one from an SME development agency, each with > 10 years of experience), and two SME owners/managers, who collectively determined that a lag of twelve and eighteen months to separate the predictor and outcome variables was appropriate, specifically because performance appraisals, increments, and promotions in SMEs in Pakistan are typically performed on an annual basis, and thus the effect of an ethics-oriented HRM system could be identified once all these practices are put in place.

Participants and Procedures

Participants of this study were full-time employees of SMEs in Pakistan. For SMEs, employee deviance is a persistent problem (Ji et al., 2019; Longenecker et al., 2006). In SMEs, activities such as inappropriate use of business resources, opportunism, lack of confidentiality, favoritism, and embezzlement are prevalent (Ji et al., 2019). Further, being more labor-intensive, resource-scarce, and adhocratic in nature, SMEs are more likely to be exposed to and be impacted by employee DWB (Ji et al., 2019). As such, SMEs are well suited to conducting research on DWBs.

We obtained a list of approximately 2,500 individuals through government institutions that work exclusively for the development of SMEs in Pakistan. Since the focus of this study was HRM systems, in consultation with the institutions, we selected 1,500 employees whose organizations had formal HR departments in place (in Pakistan, some SMEs still follow the traditional approach of managing human resources through the administration office). We sent the survey to individual participants through email; bounced-back emails due to wrong or inactive email addresses brought the final number down to 1,050 individuals. We emphasized that participation in the survey was voluntary, that they could withdraw at any stage, and that their personal and institutional confidentiality would be ensured.

In the first wave, we received 440 individual responses after three reminders, forming a 40% response rate. In the second wave, after three reminders and excluding employees who had left the organization, we received 295 responses. In the third wave, after three follow-ups, we obtained 245 employee-supervisor matched responses. In order to obtain employees’ DWB rating from their supervisors, we obtained the contact details of supervisors directly from the individuals in initial waves. We dropped 13 incomplete responses; thus, the final sample size comprised 232 individual responses from 84 organizations, forming a final individual-level response rate of 20%. An average of 2.7 responses was obtained from each organization, with a maximum of 5 and a minimum of 2. In our sample, 58.2% of the responses were from the services sector, 87.1% from SMEs with more than 50 employees, and 58.6% from family-owned/entrepreneurial ventures. The typical respondent had at least 14 years of education (81%), was aged between 25–38 years (68%), had 4–5 years of tenure with the current organization (77%) and had 6–10 years’ experience in total (66%).

Measures

We followed the recommendations of Colquitt et al. (2019) and Hinkin (1995) to construct our measurement scales. All the measures used in this study were selected after consultation with our expert panel (see above). We conducted a focus group with 15 Executive MBA working professionals to ensure the relevance of items. Prior to the full survey, we conducted a pilot test with 25 employees who found all items to be comprehensible and relevant. A list of all items can be found in Appendix 1.

Employee DWB. Employee DWB was measured with 12 items taken from Peterson (2002). Supervisors rated DWB of employees on a five-point Likert scale (1- never, 5- always). The composite reliability score of this scale was 0.95.

Ethics-oriented HRM systems. We measured ethics-oriented HRM systems based on the original 17-item scale developed by Guerci et al. (2015). We followed guidelines suggested by Colquitt et al. (2019) to select items to fit the ethics orientation of HRM systems’ practices in the SME context. For instance, “Training interventions that focus on the values of the organization” was modified with the addition of “ethical and moral values.” In contrast, the questions related to “the involvement of the union” and “employee volunteer programs” were not relevant for SMEs. Accordingly, as per expert panel advice and the feedback provided by focus group and pilot test, two items were dropped, and a few items were re-worded while keeping the original message intact. The final ethics-oriented HRM system scale consisted of 15 items measuring organizational HRM practices on the enhancement of ethical ability, motivation, and opportunity among employees. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) revealed a superior model fit (χ2 = 183.55; χ2/df = 2.15; CFI = 0.96; TLI = 0.95; and RMSEA = 0.07) for the single factor, with all factor loadings significant and above 0.70. The composite reliability score for this construct was 0.96. Respondents used a 5-point Likert scale (1-never, 5-always) to indicate the presence of respective HRM practices.

Given that the ethics-oriented HRM system was rated by individual employees, we calculated interrater agreement (rwg), intra-class correlations (ICC1), and the reliability of the group mean (ICC2) (Bliese, 2000). The rwg score was 0.95, above the cut-off point of 0.70 (Castro, 2002). The ICC1 score was 0.28 and the ICC2 value was 0.76, which was above the recommended cut-off of 0.60 (Bliese, 2000). These values indicated the suitability of the aggregation of individual-level responses to form the organization level construct (Klein & Kozlowski, 2000).

Moral Attentiveness. Moral attentiveness was measured using Reynolds’ (2008) 12-item scale, with 7 items assessing perceptual moral attentiveness, and five items assessing reflective moral attentiveness. Responses were measured on a five-point Likert scale (1-strongly disagree, 5-strongly agree). The composite reliability scores for the perceptual and reflective dimensions were 0.90 and 0.87, respectively.

Gender and Income. Gender was measured as a dichotomous variable with “0” indicating female and “1” indicating male. Income was measured using an ordinal scale against four categories with 1 indicating up to PKR. 300,000 (ca. US$ 2,000); 2 = PKR. 300,001–600,000 (ca. $US 4,000), 3 = PKR. 600,001–1,200,000 (ca. $US 8,000), and 4 = PKR. 1,200,001–3,600,000 (ca. $US 24,000).

Control Variables. Extant literature suggests that certain demographic characteristics may influence an individual’s tendency to engage in deviant behaviors (Lee & Allen, 2002). Therefore, in this study, based on prior empirical research, service tenure and employee education level, as well as age, industry, and size of the organization, were included as controls.

Results

To determine the convergent and discriminant validity of measures, we conducted confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). The full model comparison results are presented in Table 1. The hypothesized four-factor model demonstrates good fit to the data and is superior to alternative three-factor (i.e., combining PMA and RMA) as well as single-factor models. All factor loadings of our hypothesized four factors model were statistically significant and in the range of 0.65 and 0.85 (except one item). Furthermore, the average variance extracted (AVE) of all variables was above the threshold value of 0.50 (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Our analyses established the statistical distinctiveness and adequacy of the psychometric properties of the measures, which were consistent with prior research (Chuang et al., 2016; Liao et al., 2009) and confirmed discriminant and convergent validity of all measures present in our model.

Descriptive Statistics

The descriptive statistics and correlations for the final variables are presented in Table 2. Most of the control variables correlate significantly with DWB and are thus incorporated as controls in further analyses. Given that the literature acknowledges conceptual proximity between perceptual and reflective moral attentiveness (Reynolds, 2008), we employed statistical techniques to calculate the Tolerance level, Variance Inflation Factor (VIF), eigenvalue, and condition index to refute the possible issue of multicollinearity in our model. The value of Tolerance was above the threshold value of 0.2, VIF was below the threshold value of 5, eigenvalue was not close to zero, and the condition index was less than 15 for all predictor variables (Hair et al., 2006). Therefore, multicollinearity was not found to affect our model.

Analytical Strategy

The data in this study were multilevel as the mediators (i.e., PMA and RMA), moderators (i.e., gender and income), and the outcome variable (i.e., DWB) were measured at the individual level, whereas the predictor variable (ethics-oriented HRM system) was measured at the organization level. Therefore, we employed multilevel modeling to investigate the effect of Level 2 ethics-oriented HR system (n = 84) on Level 1 individual’s moral and behavioral outcome (n = 232).

We employed the MLMed macro with restricted maximum likelihood estimation in combination with PROCESS macro to test all direct, mediation, and moderated mediation hypotheses (Hayes & Rockwood, 2020). HRM scholars have found MLMed a suitable macro to test a 2–1-1 multilevel model (see Okay-Somerville & Scholarios, 2019). MLMed automatically grand mean centers the individual‐level variables to control intra‐individual influences on between‐group relationships (Hayes & Rockwood, 2020). It also uses group mean centering, which removes the effects of between‐group confounds from the individual-level (level 1) variables to allow for a better understanding of relationships among the cross-level variables and interactions. Additionally, MLMed uses the Monte Carlo method to calculate confidence intervals for the indirect effects, a requirement in multilevel mediation models (Preacher & Selig, 2012), which is a reliable test for indirect effects because it does not assume normal distributions of indirect effects.

Given that the multilevel analysis produces both “within” and “between” effects, researchers need to consider the theoretically relevant level to analyze the data. Zhang et al. (2019) and Zhang et al. (2009) suggest that if the predictor variable in multilevel mediation modeling is a Level-2 factor, only between-groups mediating effects should be considered. “Because the within-group relationship under (Level 2) is independent of the between-group relationship, a mediation estimate combining the two will serve to make ambiguous the 2–1-1 mediation effect” (Zhang et al., 2009, p. 704). Accordingly, consistent with the extant studies (Kehoe & Wright, 2013; Song et al., 2019), we considered the between-group scores to measure the effect of Level 2 predictor (i.e., the organization’s ethics-oriented HRM system) on Level 1 outcomes (i.e., employee moral attentiveness and DWB) in all hypotheses, including moderated mediation where the interaction of Level 2 variable was created with Level 1 moderators (i.e., gender and income). We also calculated values at ± 1 SD level of the mean of moderators. All indirect effects were tested using Monte Carlo simulations with a sample size of 10,000 and CI set at 95% (Preacher & Selig, 2012).

Null Model

We used SPSS linear mixed models and restricted maximum likelihood estimation to test null models with no predictors to calculate the intraclass correlation coefficients and understand the extent to which DWB vary across organizations. As shown in the Null model in Table 3, the ICC (intra-class correlation) score suggested significant variance across organizations for DWB (86%) (Wald Z = 6.17, p = 0.001). This value was significant and well above the recommended between-group variance range of 15% to warrant multilevel analysis (Podsakoff et al., 2019).

Hypothesis Testing

Our first hypothesis postulated a negative relationship between ethics-oriented HRM systems and DWB. The findings (Table 3 Model 1) revealed that time 1 ethics-oriented HRM systems have a significant cross-level negative effect on time 3 DWB (β = -0.32, S.E = 0.066, t = -4.82, p = 0.001), in support of Hypothesis 1.

In Table 4 we present the full results of our mediated-moderated model. Hypothesis 2a proposed that PMA mediates the relationship between ethics-oriented HRM systems and DWB. In support of Hypothesis 2a, Table 4 shows a significant indirect effect of Time 1 ethics-oriented HRM systems on Time 3 DWB through Time 2 PMA (β = -0.19, S.E = 0.09, Z = -2.10, p = 0.031, 95% CI: [-0.3586, -0.0170]) at the between-group level. The direct effect of ethics-oriented HRM systems on DWB in the presence of PMA was not significant (β = -0.15, p = 0.184, 95%: CI [-0.3852, 0.0755]). Hypothesis 2b proposed that RMA mediates the relationship between ethics-oriented HRM systems and DWB. In support of Hypothesis 2b, Table 4 shows a significant indirect effect of Time 1 ethics-oriented HRM systems on Time 3 DWB through Time 2 RMA (β = -0.35, S.E = 0.07, Z = -4.69, p = 0.001, 95% CI: [-0.5066, -0.2170]) at the between-group level. The direct effect of ethics-oriented HRM systems on DWB in the presence of RMA was not significant (β = 0.03, p = 0.744, 95% CI: [-0.1463, 0.2064].

Hypothesis 3a proposed that employee gender moderates the indirect effect of ethics-oriented HRM systems on DWB through PMA, such that the indirect effect will be stronger for women than for men. We ran a moderated-mediated model with gender as first-stage moderator. Hayes (2013) asserts that the existence of a statistically significant moderator in any stage of the mediation process indicates its potential to modify the strength of the indirect effects. Table 4 shows that the conditional between-group indirect effect was significant with β = − 0.38, S.E = 0.18, Z = − 2.12, p = 0.032, 95% CI: [− 0.7711, − 0.0446]. The between-index of moderated mediation (estimate = 0.110, 95% CI: [0.0078, 0.2645]) explained significant variance in the indirect relationship between ethics-oriented HRM systems and DWB through PMA due to gender. Specifically, the effect of the indirect relationship was bigger and significant for female employees (β = − 0.16, S.E. = 0.07, 95% CI: [− 0.2863, − 0.0293]), and became weaker but still significant for male employees (estimate = − 0.09, S.E. = 0.04, 95% CI: [− 0.1800, − 0.0179]). Thus, our findings support Hypothesis 3a.

Hypothesis 3b proposed that employee gender moderates the indirect effect of ethics-oriented HRM systems on DWB through RMA, such that the indirect effect will be stronger for women than for men. We ran a moderated-mediated model with gender as first-stage moderator. The conditional indirect effect, presented in Table 4, was significant with β = − 0.66, S.E = 0.18, Z = − 3.67, p = 0.001, 95% CI: [− 1.061, − 0.3443], but the between‐index of moderated mediation was not significant (β = 0.18, 95% CI interval [− 0.0018, 0.3868]). Thus, Hypothesis 3b was not supported. The effect of the indirect relationship was bigger and statistically significant for female employees (estimate = − 0.34, S.E. = 0.05, 95% CI: [− 0.4357, − 0.2481]), and it became weaker but still significant for male employees (estimate = − 0.21, S.E. = 0.06, 95% CI: [− 0.3215, − 0.1027]).

Hypothesis 4a proposed that employee income level moderates the indirect effect of ethics-oriented HRM systems on DWB through PMA, such that the indirect effect will be stronger for lower-income than higher-income individuals. We ran a moderated-mediated model with income level as first-stage moderator. As presented in Table 4, the conditional indirect effect was significant with β = − 0.32, S.E = 0.14, Z = − 2.01, p = 0.023, 95% CI: [− 0.6306, − 0.0371]. Employee income level explained significant variance in the indirect relationship between ethics-oriented HRM systems and DWB through PMA as the between‐index of moderated mediation was significant (β = 0.05, 95% CI: [0.0044, 0.1140]). Specifically, the effect of the indirect relationship was bigger and significant for lower-income employees (estimate = − 0.17, S.E. = 0.06, 95% CI: [− 0.3008, − 0.0396]), and smaller but still significant when the employee income level was high (estimate = -0.07, S.E. = 0.03, 95% CI: [− 0.1278, − 0.0147]). This supports Hypothesis 4a.

Hypothesis 4b proposed that employee income level moderates the indirect effect of ethics-oriented HRM systems on DWB through RMA, such that the indirect effect will be stronger for lower-income rather than higher-income individuals. We ran a moderated-mediated model with income level as first-stage moderator. Table 4 shows that the conditional indirect effect was significant with β = − 0.59, S.E = 0.12, Z = − 4.77, p = 0.001, 95% CI: [− 0.8529, − 0.3646]. The between‐index of moderated mediation was significant (β = 0.09, 95% CI: [0.0376, 0.1662]). Specifically, the effect of the indirect relationship was bigger and significant for lower-income employees (β = − 0.38, S.E. = 0.05, 95% CI: [− 0.4781, − 0.2830]), and it became weaker and insignificant when the employee income level was high (β = − 0.09, S.E. = 0.04, 95% CI: [− 0.1827, 0.0033]). Thus, Hypothesis 4b was supported.

Discussion

In response to calls for scientific studies identifying new approaches to deal with persistent challenges of workplace deviance, we drew from the theory of moral development to understand the linkages between ethics-oriented HRM systems, moral attentiveness, and employee DWB, as well as the boundary conditions of these relationships. Our multi-source, multi-wave survey conducted among 232 employees (and their supervisors) of 84 SMEs in Pakistan lent support to our hypotheses. Our multilevel analysis found that ethics-oriented HRM systems influence employee DWB both directly and indirectly through perceptual and reflective moral attentiveness. Further, employee gender and income moderate these indirect effects in such a way that the indirect effects were stronger among women and lower-income individuals.

Theoretical Implications

Our study generates three theoretical contributions. The first contribution is the integration of the targeted approach of strategic HRM and the theory of moral development to better explain how strategically targeted ethics-oriented HRM systems operate across levels to affect employees’ moral cognitive processes and unethical behaviors. Our explicit conceptualization of ethics-oriented HRM system as an inhibitor of DWB adheres to the theory of strategically targeted HRM systems, which states that the design and configuration of HRM systems should be targeted at strategic organizational objectives and behaviors (Jiang & Messersmith, 2018). In so doing, our study extends prior research on HRM and ethics that has predominantly adopted a performance-oriented approach to consider HRM systems as an inhibitor of unethical behaviors. Specifically, we go beyond recent research that has conceptualized ethics-oriented HRM systems as an individual-level predictor of perceived ethical climate in one organization (Guerci et al., 2015, 2017) to suggest that ethics-oriented HRM systems deter DWB, across levels, by building employees’ moral capacity (Reinecke & Ansari, 2015) to place morality higher in their values system, to take moral courses of action, and to take personal responsibility for moral outcomes (Narvaez & Lapsley, 2009).

Second, in tackling the “black box” between HRM systems and DWB, this study explicates perceptual and reflective moral attentiveness as two novel mechanisms linking ethics-oriented HRM systems with DWB. It enriches prior research of ethical climate as an immediate outcome of ethics-oriented HRM, as ethical climate only depicts what employees perceive is expected and rewarded by the organization. Instead, our findings confirm that perceptual and reflective moral attentiveness as mediators describe how ethics-oriented HRM systems operate to influence moral cognition of employees in ways that regulate their (un)ethical behavior. It echoes the argument that DWB is not solely exogenous but also reflects individuals’ underlying regulatory process of moral cognition (Fiske & Taylor, 1991; Miao et al., 2020). Adding to previous studies which examined the role of RMA in shaping (un)ethical behaviors (Miao et al., 2020; Moore & Gino, 2015), our multilevel investigation suggests that the ethics-oriented HRM systems can inhibit DWB by helping develop and activate employees’ perceptual and reflective moral cognitive frameworks (Dawson, 2018; Wurthmann, 2013). Insights from our findings may help generate a more nuanced cognizance of DWB, its determinants, and underlying reasoning (Henle et al., 2005; Mitchell et al., 2017).

Third, we identified how two individual demographic differences with moral implications—gender and income level—intervene to impact employees’ moral cognitive and behavioral reactions to ethics-oriented HRM systems. This finding extends the theory of moral development by identifying boundary conditions that influence the effectiveness of organizational moral interventions in developing employee moral capacity. Our test of the moderating effects of gender and income on the mediated effect of ethics-oriented HRM system on DWB, also responds to the call for the integrated multilevel models to capture HRM system’s effect at employee level (Shin et al., 2020). Consistent with previous studies showing that women were more welcoming to ethical interventions in general (Deshpande, 1997), our results show that the indirect effect of ethics-oriented HRM system on employee DWB via PMA is stronger among women than men. We surmise that women are more receptive to ethics-oriented HRM systems in augmenting their PMA due to their mental schema to process ethical information more empathetically as well as their propensity to meet organizational expectations of responsible conduct (Kacmar et al., 2011). Future research could explore these ideas further, for instance through experiments.

In addition, we found that the indirect effect of ethics-oriented HRM on employee DWB via PMA and RMA was stronger among lower-income individuals than higher-income individuals. This builds on research showing that individuals of different income levels exhibit different moral values and behaviors at the workplace (Siu & Lam, 2009). This finding could mean that lower-income employees’ increased salience of fairness and equitability helps them respond to ethics-oriented HRM systems to develop their moral schemas by exhibiting morally informed decisions and behaviors, which subsequently reduces their DWB. Or, the rewards and punishments associated with (un)ethical behaviors render lower-income employees to re-evaluate the cost-benefits of engaging in DWB. These moderated-mediation findings imply that the processes through which ethics-oriented interventions generate the desired ethical outcomes among employees are subject to individual differences that have important ethical implications.

Practical Implications

Our study suggests that ethics-oriented HRM systems offer organizations an opportunity to mitigate DWB by employing and developing individuals who possess higher levels of moral development (Guerci et al., 2015; Tay et al., 2017; Valentine et al., 2014). Through ethics-oriented HRM practices such as ethics-based selection, training, compensation, and job design, employees can perform better by independently interpreting situations and construing decisions and behaviors with higher moral input and by considering their moral implications for organizational performance (Egorov et al., 2019; Guerci et al., 2015; 2015). Reducing deviant workplace behaviors can bring numerous benefits to organizations, including improved productivity, increased employee morale, enhanced market reputation, legal compliance, cost savings, and most importantly an overall positive work environment (Mackey et al., 2021). As such, managers need to start building ethics-oriented HRM policies and practices as well as assessing the moral attentiveness of current and potential employees to increase the accessibility of their employees’ moral cognitive frameworks. In addition, to maximize the effectiveness of ethics-oriented HRM systems, managers need to consider the moral implications of employee-level attributes. The present findings suggest that gender and income level significantly differentiate the effectiveness of ethics-oriented HRM systems. Managers need to develop a strategy to enhance the engagement of men and higher-income groups to promote moral attentiveness and reduce DWB. This may require managers to tailor HRM practices to fit different groups of people.

Limitations and Future Directions

Our study is also subject to a few limitations. Firstly, the measurement indicators used for ethics-oriented HRM practices focus on the frequency of their implementation but not on other elements such as level of sophistication or coverage (cf. Guerci et al., 2015). Therefore, future studies can assess the implementation of ethics-oriented HRM practices and policies in terms of their strength and quality by using alternative measurements. Second, future studies may benefit by incorporating other morality-based individual differences such as moral identity, moral courage, and moral resilience when testing the hypothesized framework. Third, we have assumed that extrinsic motivation stressed through incentives and rewards will enhance moral cognition and behaviors. However, the literature also indicates that extrinsic motivators may hinder discretionary behaviors (Bock et al., 2005; Jiang et al., 2012). Thus, future studies may frame the dual effects of the transactional aspects of ethics-oriented HRM systems. Finally, we focus on SMEs in a developing-country context because of the immediacy of these relationships in smaller firms and the significance of DWB in weaker institutional environments. In fact, Wang and Murnighan (2014) showed that country-level GDP per capita, public ethics index, societal equality, and individualism/uncertainty avoidance culture were negatively related to individuals’ approval of unethical behavior. Future research could examine these relationships in larger firms and in other country contexts.

Despite these limitations, this study contributes to an enhanced understanding of how certain ethics-oriented HRM practices impact employees’ deviant behaviors via moral attentiveness. The finding regarding the significant moderation of gender opens up a new avenue of future research on the gender effect of performance-based or other types of strategically targeted HRM systems on employee outcomes. Given that previous research (Shin et al., 2020) as well as our own shows that women are more receptive to ethics-oriented HRM systems, it would be intriguing to find out if gender moderation holds for other types of targeted HRM systems that are concerned about relationships with others, such as corporate social responsibility and service quality. Likewise, our finding of income level as a moderator of the indirect relationship between ethics-oriented HRM systems and DWB via moral attentiveness paves the foundation for future research of income moderation on other types of ethical interventions, as well as on other types of HRM systems.

Conclusion

Employee DWB is a matter of deep concern for organizations. The present study theorizes that ethics-oriented HRM systems can play a crucial role in minimizing such negative behaviors. If organizations emphasize developing such HRM systems, they will help their employees to become more morally attentive towards ethical issues, which consequently leads to a decrease in DWB. Furthermore, women and employees with low income are particularly receptive to ethics-oriented HRM systems in boosting their perceptive and reflective moral attentiveness and subsequently reducing DWB.

Appendix 1. Measurement Scale Items

Ethics-oriented HRM scale items |

|---|

1. Attracting and selecting employees who share higher moral/ethical values |

2. Hiring employees who exhibit relatively high levels of moral/ethical development |

3. Training interventions that focus on moral/ethical values of the organization |

4. Presence of ethical leadership development programs/training |

5. Creating cognitive conflict to stimulate independent decision-making in ethically ambiguous situations |

6. Developing performance goals that focus on means as well as on ends i.e. using not only outcome-based but also behavior-based performance evaluations |

7. Linking bonuses and pay (rewards) to moral/ethical behaviors based on social performance objectives |

8. Promoting awards for good citizenship (moral/ethical behaviors) |

9. Sanctions (penalties/punishments) for breaching/going against the organization’s moral/ethical standards 10. Job design encourages employees to take ethical/moral decisions 11. Encouraging employees to provide recommendation/solutions when the organization faces moral/ethical problems 12. Encouraging the reporting of unethical behaviour and supporting whistle-blowing on moral/ethical issues 13. Career growth mechanism (promotions, transfers etc.) is fair, visible to all and linked to the respect of organizational moral/ethical standards |

14. Involving employees in the design, application and review of the ethical infrastructure (policies, procedures, conduct) of the organization |

15. Encouraging communications with stakeholders about important moral/ethical issues |

Moral attentiveness (perceptual and reflective) |

1. In a typical day, I face several moral/ethical dilemmas |

2. I often have to choose between doing what’s right and doing something that’s wrong |

3. I regularly face decisions that have significant moral/ethical implications/consequences |

4. My life has been filled with one moral predicament/problem after another |

5. Many of the decisions that I make have moral/ethical dimensions to them |

6. I regularly think about the moral/ethical implications/consequences of my decisions |

7. I frequently encounter moral/ethical situations |

8. I think about the morality/ethicality of my actions almost every day |

9. I rarely face moral/ethical dilemmas |

10. I often find myself pondering/thinking about moral/ethical issues |

11. I often reflect on the moral/ethical aspects of my decisions |

12. I like to think about morality/ethics |

Deviance work behaviors |

1. Worked on a personal matter instead of working for my employer |

2. Intentionally worked slower than s/he could have worked |

3. Taken an additional or a longer break than is acceptable |

4. Showed favoritism for a fellow employee or subordinate employee |

5. Blamed someone else or let someone else take the blame for his/her mistake |

6. Repeated gossip about a co-worker |

7. Padded an expense account (claimed more expenses) to get reimbursed for more money s/he spent on business expenses |

8. Taken property (things/supplies) from work without permission |

9. Cursed(abused) at someone at work |

10. Made an ethnic or sexually harassing/inappropriate remark or joke at work |

11. Made someone feel physically intimidated (uncomfortable/threatened) either through threats or carelessness at work |

12. Accepted a gift/favor in exchange for preferential/special treatment |

Data availability

The data is available with 1st author upon a reasonable request.

Change history

31 August 2023

The original version of this article was revised: In this article the affiliation details for Author Farheen Rizvi were incorrect.

05 September 2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-023-05525-7

References

Arthur, J. B. (2011). Do HR system characteristics affect the frequency of interpersonal deviance in organizations? The role of team autonomy and internal labor market practices. Industrial Relations: A Journal of Economy and Society, 50(1), 30–56.

Atabay, G., Çangarli, B. G., & Penbek, Ş. (2015). Impact of ethical climate on moral distress revisited: Multidimensional view. Nursing Ethics, 22(1), 103–116.

Bandura, A. (1991). Social cognitive theory of self-regulation. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 248–287.

Beauducel, A., & Wittmann, W. W. (2005). Simulation study on fit indexes in CFA based on data with slightly distorted simple structure. Structural Equation Modeling, 12(1), 41–75.

Bing, M. N., Stewart, S. M., Davison, H. K., Green, P. D., McIntyre, M. D., & James, L. R. (2007). An integrative typology of personality assessment for aggression: Implications for predicting counterproductive workplace behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(3), 722–744.

Blau, P. M. (1964). Justice in social exchange. Sociological Inquiry, 34(2), 193–206.

Bliese, P. D. (2000). Within-group agreement, non-independence, and reliability: Implications for data aggregation and analysis. In K. J. Klein & S. W. J. Kozlowski (Eds.), Multilevel theory, research, and methods in organizations: Foundations, extensions, and new directions (pp. 349–381). Jossey-Bass.

Boatright, J. R. (2013). Confronting ethical dilemmas in the workplace (pp. 6–9). USA: Taylor and Francis. vol. 69.

Bock, G. W., Zmud, R. W., Kim, Y. G., & Lee, J. N. (2005). Behavioral intention formation in knowledge sharing: Examining the roles of extrinsic motivators, social-psychological forces, and organizational climate. MIS Quarterly, 9(1), 87–111.

Bolin, A., & Heatherly, L. (2001). Predictors of employee deviance: The relationship between bad attitudes and bad behavior. Journal of Business and Psychology, 15(3), 405–418.

Bureau, J., Mageau, G., Morin, A., Gagné, M., Forest, J., Papachristopoulos, K., & Parenteau, C. (2018). Promoting autonomy to reduce employee deviance: The mediating role of identified motivation. International Journal of Business and Management, 13(5), 61–71.

Castro, S. L. (2002). Data analytic methods for the analysis of multilevel questions: a comparison of intraclass correlation coefficients, rwg (j), hierarchical linear modeling, within-and between-analysis, and random group resampling. The Leadership Quarterly, 13(1), 69–93.

Chen, M., Chen, C. C., & Sheldon, O. J. (2016). Relaxing moral reasoning to win: How organizational identification relates to unethical pro-organizational behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 101(8), 1082–1096.

Chiu, S. F., & Peng, J. C. (2008). The relationship between psychological contract breach and employee deviance: the moderating role of hostile attributional style. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 73(3), 426–433.

Chuang, C. H., Jackson, S. E., & Jiang, Y. (2016). Can knowledge-intensive teamwork be managed? Examining the roles of HRM systems, leadership, and tacit knowledge. Journal of Management, 42(2), 524–554.

Chung, J. O., & Hsu, S. H. (2017). The effect of cognitive moral development on honesty in managerial reporting. Journal of Business Ethics, 145(3), 563–575.

Clark, A. E., & Senik, C. (2010). Who compares to whom? The anatomy of income comparisons in Europe. The Economic Journal, 120(544), 573–594.

Collins, C. J., & Clark, K. D. (2003). Strategic human resource practices, top management team social networks, and firm performance: the role of human resource practices in creating organizational competitive advantage. Academy of Management Journal, 46(6), 740–751.

Colquitt, J. A., Sabey, T. B., Rodell, J. B., & Hill, E. T. (2019). Content validation guidelines: Evaluation criteria for definitional correspondence and definitional distinctiveness. Journal of Applied Psychology, 104(10), 1243.

Culiberg, B., & Mihelič, K. K. (2016). Three ethical frames of reference: insights into Millennials’ ethical judgements and intentions in the workplace. Business Ethics: A European Review, 25(1), 94–111.

Davison, H. K., LeBreton, J. M., Stewart, S. M., & Bing, M. N. (2020). Investigating curvilinear relationships of explicit and implicit aggression with workplace outcomes. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 29(4), 501–514.

Dawson, D. (2018). Organisational virtue, moral attentiveness, and the perceived role of ethics and social responsibility in business: The case of UK HR practitioners. Journal of Business Ethics, 148(4), 765–781.

De Cristofaro, V., Pellegrini, V., Giacomantonio, M., Livi, S., & van Zomeren, M. (2021). Can moral convictions against gender inequality overpower system justification effects? Examining the interaction between moral conviction and system justification. British Journal of Social Psychology, 60(4), 1279–1302.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self determination in human behavior. Plenum.

Deshpande, S. P. (1997). Managers’ perception of proper ethical conduct: The effect of sex, age, and level of education. Journal of Business Ethics, 16(1), 79–85.

Di Stefano, G., Scrima, F., & Parry, E. (2019). The effect of organizational culture on deviant behaviors in the workplace. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 30(17), 2482–2503.

Dixon, J., Levine, M., Reicher, S., & Durrheim, K. (2012). Beyond prejudice: Are negative evaluations the problem and is getting us to like one another more the solution? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 35(6), 411–425.

Egorov, M., Verdorfer, A. P., & Peus, C. (2019). Taming the emotional dog: Moral intuition and ethically-oriented leader development. Journal of Business Ethics, 160(3), 817–834.

Ferris, D. L., Spence, J. R., Brown, D. J., & Heller, D. (2012). Interpersonal injustice and workplace deviance: The role of esteem threat. Journal of Management, 38(6), 1788–1811.

Fiske, S. T., & Taylor, S. E. (1991). Social cognition. Mcgraw-Hill Book Company.

Flanagan, O., & Jackson, K. (1987). Justice, care, and gender: the Kohlberg-Gilligan debate revisited. Ethics, 97(3), 622–637.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Sage.

Frey, B. S., & Oberholzer-Gee, F. (1997). The cost of price incentives: an empirical analysis of motivation crowding-out. The American Economic Review, 87(4), 746–755.

George, J. M., & Jones, G. R. (2000). The role of time in theory and theory building. Journal of Management, 26(4), 657–684.

Gerhart, B., Wright, P. M., McMahan, G. C., & Snell, S. A. (2000). Measurement error in research on human resources and firm performance: How much error is there and how does it influence effect size estimates? Personnel Psychology, 53(4), 803–834.

Gilligan, C. (1982). In a Different Voice: Psychological Theory and Women’s Development. Harvard U. University Press.

Gino, F., & Pierce, L. (2009). The abundance effect: Unethical behavior in the presence of wealth. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 109(2), 142–155.

Götz, M., Bollmann, G., & O’Boyle, E. H. (2019). Contextual undertow of workplace deviance by and within units: a systematic review. Small Group Research, 50(1), 39–80.

Gould-Williams, J. (2007). HR practices, organizational climate and employee outcomes: Evaluating social exchange relationships in local government. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 18(9), 1627–1647.

Griffin, R. W., & Lopez, Y. P. (2005). “Bad behavior” in organizations: A review and typology for future research. Journal of Management, 31(6), 988–1005.

Guerci, M., Radaelli, G., Siletti, E., Cirella, S., & Shani, A. R. (2015). The impact of human resource management practices and corporate sustainability on organizational ethical climates: An employee perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 126(2), 325–342.

Guerci, M., Radaelli, G., Battisti, F. D., & Siletti, E. (2017). Empirical insights on the nature of synergies among HRM policies - An analysis of an ethics-oriented HRM system. Journal of Business Research, 71(1), 66–73.

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Tatham, R. L. (2006). Multivariate Data Analysis (6th ed.). Pearson Education International.

Hannah, S. T., Avolio, B. J., & May, D. R. (2011). Moral maturation and moral conation: A capacity approach to explaining moral thought and action. Academy of Management Review, 36(4), 663–685.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Press.

Hayes, A. F., & Rockwood, N. J. (2020). Conditional process analysis: Concepts, computation, and advances in the modeling of the contingencies of mechanisms. American Behavioral Scientist, 64(1), 19–54.

Heilman, M. E. (2012). Gender stereotypes and workplace bias. Research in Organizational Behavior, 32, 113–135.

Henle, C. A., Giacalone, R. A., & Jurkiewicz, C. L. (2005). The role of ethical ideology in workplace deviance. Journal of Business Ethics, 56(3), 219–230.

Hinkin, T. R. (1995). A review of scale development practices in the study of organizations. Journal of Management, 21(5), 967–988.

Hong, N. T. (2019). Unintentional unethical behavior: The mediating and moderating roles of mindfulness. International Journal of Ethics and Systems, 36(1), 98–118.

Hong, Y., Jiang, Y., Liao, H., & Sturman, M. C. (2017). High performance work systems for service quality: Boundary conditions and influence processes. Human Resource Management, 56(5), 747–767.

Hsieh, H. H., & Wang, Y. D. (2016). Linking perceived ethical climate to organizational deviance: The cognitive, affective, and attitudinal mechanisms. Journal of Business Research, 69(9), 3600–3608.

Hu, X., & Jiang, Z. (2018). Employee-oriented HRM and voice behavior: A moderated mediation model of moral identity and trust in management. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 29(5), 746–771.

Hu, J., Erdogan, B., Bauer, T. N., Jiang, K., Liu, S., & Li, Y. (2015). There are lots of big fish in this pond: The role of peer overqualification on task significance, perceived fit, and performance for overqualified employees. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(4), 1228.

Huang, L., & Paterson, T. A. (2017). Group ethical voice: Influence of ethical leadership and impact on ethical performance. Journal of Management, 43(4), 1157–1184.

Huiras, J., Uggen, C., & McMorris, B. (2000). Career jobs, survival jobs, and employee deviance: A social investment model of workplace misconduct. The Sociological Quarterly, 41(2), 245–263.

Jackson, S. E., Schuler, R. S., & Jiang, K. (2014). An aspirational framework for strategic human resource management. Academy of Management Annals, 8(1), 1–56.

Jennings, P. L., Mitchell, M. S., & Hannah, S. T. (2015). The moral self: A review and integration of the literature. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36(S1), 104–168.

Ji, J., Dimitratos, P., Huang, Q., & Su, T. (2019). Everyday-life business deviance among Chinese SME owners. Journal of Business Ethics, 155(4), 1179–1194.

Jiang, K., & Messersmith, J. (2018). On the shoulders of giants: A meta-review of strategic human resource management. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 29(1), 6–33.

Jiang, K., Lepak, D. P., Han, K., Hong, Y., Kim, A., & Winkler, A. L. (2012). Clarifying the construct of human resource systems: Relating human resource management to employee performance. Human Resource Management Review, 22(2), 73–85.

Kacmar, K. M., Bachrach, D. G., Harris, K. J., & Zivnuska, S. (2011). Fostering good citizenship through ethical leadership: Exploring the moderating role of gender and organizational politics. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(3), 633–642.

Kehoe, R. R., & Wright, P. M. (2013). The impact of high-performance human resource practices on employees’ attitudes and behaviors. Journal of Management, 39(2), 366–391.

Kidwell, R. E., Jr., & Kochanowski, S. M. (2005). The morality of employee theft: Teaching about ethics and deviant behavior in the workplace. Journal of Management Education, 29(1), 135–152.

Klein, K. J., & Kozlowski, S. W. (2000). From micro to meso: Critical steps in conceptualizing and conducting multilevel research. Organizational Research Methods, 3(3), 211–236.

Kohlberg, L. (1976). Moral stages and moralization: The cognitive developmental approach. In T. Lickona (Ed.), Moral development and behavior (pp. 31–53). Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Kohlberg, L. (1981). Essays on moral development. Harper and Row.

Larkin, I., Pierce, L., Shalvi, S., & Tenbrunsel, A. (2021). The opportunities and challenges of behavioral field research on misconduct. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 166(September), 1–8.

Leana, C. R., & Meuris, J. (2015). Living to work and working to live: Income as a driver of organizational behavior. Academy of Management Annals, 9(1), 55–95.

Lee, K., & Allen, N. J. (2002). Organizational citizenship behavior and workplace deviance: the role of affect and cognitions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(1), 131–142.

Lee, M., & Kray, L. J. (2021). A gender gap in managerial span of control: Implications for the gender pay gap. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 167, 1–17.

Lee, A., Schwarz, G., Newman, A., & Legood, A. (2019). Investigating when and why psychological entitlement predicts unethical pro-organizational behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 154(1), 109–126.

Liao, H., Toya, K., Lepak, D. P., & Hong, Y. (2009). Do they see eye to eye? Management and employee perspectives of high-performance work systems and influence processes on service quality. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(2), 371–391.

Longenecker, J. G., Moore, C. W., Petty, J. W., Palich, L. E., & McKinney, J. A. (2006). Ethical attitudes in small businesses and large corporations: Theory and empirical findings from a tracking study spanning three decades. Journal of Small Business Management, 44(2), 167–183.

MacIntyre A (1984) After Virtue. Notre Dame. U of Notre Dame P.

Mackey, J. D., McAllister, C. P., Ellen, B. P., & Carson, J. E. (2021). A meta-analysis of interpersonal and organizational workplace deviance research. Journal of Management, 47(3), 597–622.

Manroop, L., Singh, P., & Ezzedeen, S. (2014). Human resource systems and ethical climates: A resource-based perspective. Human Resource Management, 53(5), 795–816.

Martinaityte, I., Sacramento, C., & Aryee, S. (2019). Delighting the customer: Creativity-oriented high-performance work systems, frontline employee creative performance, and customer satisfaction. Journal of Management, 45(2), 728–751.