Abstract

To fight climate change, firms must adopt effective and feasible carbon management practices that promote collaboration within supply chains. Engaging suppliers and customers on carbon management reduces vulnerability to climate-related risks and increases resilience and adaptability in supply chains. Therefore, it is important to understand the motives and preconditions for pursuing supply chain engagement from companies that actively engage with supply chain members in carbon management. In this study, a relational view is applied to operationalize the supply chain engagement concept to reflect the different levels of supplier and customer engagement. Based on a sample of 345 companies from the Carbon Disclosure Project’s supply chain program, the determinants of engagement were hypothesized and tested using multinomial and ordinal logistic estimation methods. The results indicate that companies that integrate climate change into their strategies and are involved in developing environmental public policy are driven by moral motives to engage their suppliers and customers in carbon management. All these factors make a stronger impact on supplier engagement than on customer engagement. Moreover, companies operating in greenhouse gas-intensive industries are driven by instrumental motives to engage their suppliers and customers because increasing greenhouse gas intensity positively influences engagement level. Company profitability appears to increase supplier engagement, but not customer engagement. Interestingly, operating in a country with stringent environmental regulations does not appear to influence supply chain engagement. By utilizing relational capabilities and collaboration, buyers can increase their suppliers’ engagement to disclose emissions, which ultimately will lead to better results in carbon management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Approximately, 3.3–3.6 billion people and a high proportion of species are vulnerable to climate change (IPCC, 2022). Actions that limit global warming, e.g., lowering industrial greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, would reduce anticipated social and economic losses and damages related to climate change in human systems and ecosystems substantially (IPCC 2022). The largest proportion of companies’ GHG emissions typically occur outside of firms’ boundaries, through operations by suppliers within firms’ supply chains (Tidy et al., 2016). For example, 75–90% of a food product’s carbon footprint is produced in the food industry’s upstream supply chain (Tidy et al., 2016), and roughly 90% of Walmart’s GHG emissions and other environmental impacts occur in its extended supply chain (Plambeck, 2012). Accounting for these emissions arising from Scope 3 sources (upstream and downstream in the supply chain) is required if firms aim to reach their carbon neutrality goals (Scope-3, 2011). For example, Kagawa et al. (2015) noted that lowering high carbon intensity in Chinese supply networks significantly decreased their customer companies’ carbon footprints in the United States and Europe. Moreover, measuring Scope 3 emissions reveals climate change-related risks in supply chains and helps companies prepare mitigation strategies (Blanco, 2021).

Underlying firms’ emission reduction strategies are their ethical considerations and motives for conducting carbon management and engaging supply chain members to pursue sustainability (Paulraj et al., 2017). The tendency to engage the supply chain to disclose emissions can be a value-driven action to foster collaboration based on a firm’s relational or moral motives, or coercive pressure with instrumental motives to control and monitor suppliers or customers to benefit only a focal firm (Paulraj et al., 2017; Peng et al., 2022; Sharfman et al., 2009; Villena & Dhanorkar, 2020). The moral motive, in which a firm has a deontological duty (Montiel, 2008) and a moral obligation to “do the right thing,” is the strongest driver of sustainability in supply chain management (Paulraj et al., 2017), and with collaboration, it can lead to far better results in the fight against climate change than unidirectional monitoring of emissions with a firm’s self-serving interests (Dahlmann & Roehrich, 2019; Dhanda & Hartman, 2011; Paulraj et al., 2017). Furthermore, firms may have relational motives to achieve legitimacy and comply with stakeholders’ norms proactively (Paulraj et al., 2017; Sarkis et al., 2010). A firm’s motives to implement carbon management—whether they are moral, relational, or instrumental—are tied to their business strategies, actions, and business environments in which supply chain engagement is executed.

Supply chain engagement is a practice that promotes transparent disclosure of emissions from both upstream and downstream in the supply chain, thereby reducing uncertainty in environmental decision-making (Blanco et al., 2017; Dahlmann and Roehrich, 2019; Wu & Pagell, 2011). However, the level and type of engagement may differ with firms’ actions and practices. The relational view (Dyer & Singh, 1998) offers a theoretical lens through which to study supplier and customer engagement levels, and it has been applied in studies on interfirm practices and relational characteristics in supply chains in terms of sustainability (Sancha et al., 2019; Zimmermann & Foerstl, 2014).

This study adopts the perspective of a focal company in a business-to-business (B2B) supply chain. According to Choi and Krause (2006), the focal company in a supply chain acts as the center and coordinator of the entire supply base, located between suppliers and customers as the designer and producer of the products and services it offers (Seuring & Müller, 2008). Thus, it plays a central role in GHG emission disclosures, engaging its supply chain members—both suppliers and customers—in carbon management. Paulraj et al. (2017) examined the firm’s motives in implementing sustainable supply chain management practices in general. Moreover, investigations have been conducted into drivers and incentives for engagement in the upstream supply chain, e.g., buyer pressure and strategy (Backman et al., 2017; Gualandris & Kalchschmidt, 2014; Villena & Dhanorkar, 2020), and industry- and country-specific features (Jira & Toffel, 2013). Extant research into downstream supply chain engagement has focused mainly on consumer behavioral perspectives and customers’ willingness to engage in sustainability initiatives (O’Brien et al., 2020). Peng et al. (2022) demonstrated that customers’ engagement deepens when they have joint instrumental motives and sustainability policies with their suppliers. However, extant studies that have examined both suppliers and customers’ engagement in connection with a focal firm’s motives for conducting sustainability initiatives, e.g., carbon management, are rare (Paulraj et al., 2017; Vachon & Klassen, 2006). Consequently, this paper answers the following question: What are the determinants and preconditions for supply chain engagement in companies’ carbon management?

To examine engagement in carbon management and firm-, industry-, and country-level features’ impacts identified in the previous literature, we used quantitative methods—more precisely, multinomial and ordinal logistic regression estimation—employing combined data from the Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP), Thomson Reuters Fundamentals, and Worldscope currently provided through the Refinitiv Eikon database, the World Bank’s DataBank, and the World Economic Forum. We applied a relational view to categorize engagement activity levels and operationalize engagement variables. This study provides evidence that integrating climate change into a company’s business strategy, being active in influencing climate change public policy, and working in GHG-intensive industries increase supply chain engagement in carbon management and are driven by different motives. Moreover, our study takes a holistic view of supply chains by investigating carbon management from a focal company’s perspective and engaging its suppliers and customers.

Relational View and Supply Chain Engagement

The relational view (Dyer & Singh, 1998), which is an extension of the resource-based view, takes a perspective beyond company boundaries to include relationships between companies. The fundamental assumption in the relational view is that all companies are embedded in a network of relationships and that “the firms’ critical resources may span firm boundaries and may be embedded in interfirm routines and processes” (Dyer & Singh, 1998, p. 661). These linkages between companies are sources of relational rents and competitive advantages (Dyer & Singh, 1998).

Studies that apply the relational view have identified two basic relationship types: arm’s length, transaction-based relationships and collaborative relationships. This builds on the basic logic of Dyer and Singh (1998), who defined relational rents of relationship-specific assets, knowledge-sharing routines, complementary resources and capabilities, and effective governance to be characteristics that distinguish relationship types from one another. Many studies in operations and supply chain management have followed this logic, not only to differentiate between relationship types, but also, for example, to differentiate between buyer–supplier management activities and practices. For example, Zimmermann and Foerstl (2014, p. 38) distinguished between nonrelational and relational supplier-facing practices by following Dyer and Singh (1998) in that a practice’s efficacy is “dependent on the mutual deployment of resources by the buyer and the supplier.” Relational practices involve knowledge sharing or joint product development. Ultimately, these resource combinations result in the creation of superior processes or lower transaction costs. Nonrelational practices, e.g., supplier evaluation or selection, require resource deployment from only the buying company and not necessarily from both parties. The relational view has not been applied to the sustainable supply chain context very frequently, but like Zimmermann and Foerstl (2014), in relation to purchasing and supply management practices, Sancha et al. (2019) applied the relational view to examine supplier management practices in the sustainability context. Sancha et al. (2019) divided sustainability practices into assessment and collaboration practices: Assessment practices are transactional and take an arm’s length approach to relationships, whereas collaboration practices are relational practices. The differences between these two types involve the buyer’s degree of involvement, which also follows the logic of Zimmermann and Foerstl (2014) and Dyer and Singh (1998).

The degree of buyers’ involvement is, indeed, what differentiates the levels of sustainability practices and activities. Dahlmann and Roehrich (2019) found three different types of climate change supply chain partner engagement based on their analysis: basic; transactional; and collaborative engagement. In the sustainable supply chain management literature, sustainability practices are categorized most commonly as monitoring (or assessment) practices and collaboration practices (Gimenez & Sierra, 2013; Sancha et al., 2016, 2019; Vachon & Klassen, 2006, 2008). Monitoring practices are arm’s length practices that aim to gather information to observe and evaluate the other party’s sustainability performance (Gualandris et al., 2015), as unidirectional and control-oriented activities (Vachon & Klassen, 2008). However, collaboration practices comprise interactions that enable the integration of knowledge and the joint development of solutions (Klassen & Vachon, 2003; Vachon & Klassen, 2006, 2008). Collaboration practices take the supplier perspective into account better and are more “supplier-friendly” than monitoring-based ones. Sancha et al. (2019) stated that with the arm’s length type of monitoring practices, the buyer passes the requirements to the supplier and expects the supplier to fulfill them, whereas in collaborative practices, the buyer’s firm invests in the relationship; thus, it takes an approach that is more based on relational and moral motives.

Following Klassen and Vachon (2003), these two practice categories can be used for both supplier and customer relations. We applied the relational view (Dyer & Singh, 1998) and used the categorization between arm’s length monitoring activities and collaboration activities to classify the different levels of supplier and customer engagement (see "Methodology" for more details).

Supply Chain Engagement’s Role in Carbon Management

A carbon management system can be defined as “a way to implement a firm’s carbon strategy or policy to enhance the efficiency of input use, mitigate emissions and risks, and avoid compliance costs or to gain a competitive advantage” (Tang & Luo, 2014, p. 84). Supply chain engagement refers to a company’s carbon management activities to engage its upstream and downstream supply chain members to achieve common goals, e.g., overcoming climate change challenges and minimizing carbon emissions throughout the supply chain (Ahi & Searcy, 2013). With relational practices and collaborative actions, supply chain engagement reduces information asymmetry and eases the interpretation of sustainability information received from both suppliers and customers (Dahlmann & Roehrich, 2019). Engagement in carbon management also includes non-governmental, market-based mechanisms that mitigate climate change globally, e.g., quality management systems standards (e.g., ISO 9000) that have spread within supply chains (Corbett, 2006). Operational improvements, e.g., technological integration of the supply chain, further promote environmental collaboration between all supply chain members (Vachon & Klassen, 2006).

Companies undertake environmental management and pursue sustainability initiatives for a variety of reasons. While Sharfman et al. (2009) divided motivations for collaborative supply chain environmental management into economic, societal, and value-driven, we followed Paulraj et al. (2017), who divided motives into instrumental, relational, and moral. A company can have an instrumental motive to seek economic benefits, e.g., improved performance and increased shareholder value (Paulraj et al., 2017; Reinhardt et al., 2008). These benefits and strategic advantages are achieved by collaborating with suppliers and customers, e.g., by working together to develop environmentally friendly goods (Blome et al., 2014; Sharfman et al., 2009). Societal reasons and pressure arise because of regulatory drivers and the company’s need to demonstrate compliance with social norms. A company proactively may undertake carbon management to achieve legitimacy in the eyes of its customers and suppliers (a relational motive), not because of short-term economic rents (Paulraj et al., 2017; Sarkis et al., 2010), but more because of relational rents. This can push companies to expand and improve their relational capabilities. Moral motivations to engage suppliers and customers in carbon management are derived from moral obligations and the deontological duty to act responsibly and as a role model for others (Montiel, 2008; Paulraj et al., 2017). Paulraj et al. (2017) demonstrated that moral motives are stronger drivers of sustainability practices than other motives.

Whatever a company’s underlying motive or reason for committing to carbon management, environmentally proactive and value-driven companies build trust-based relationships with their customers and view their suppliers as important resources. Thus, it is clear that the opportunities for carbon management are available not only within company boundaries, but also along supply chains, i.e., active collaboration with supply chain members whenever engagement is needed urgently (Blanco et al., 2016). Because different engagement levels exist due to the different kinds of engagement activities and practices (Dahlmann & Roehrich, 2019), an effort with relational collaboration-based activities that seek joint benefits could lead to better results in carbon management. Having a collaborative system in which different stakeholders are engaged in the design and implementation of sustainability assessment, as well as in narrow monitoring of carbon management’s critical tiers, fosters transparency through disclosure (Gualandris et al., 2015). Moreover, adopting carbon management systems also is connected to the existence of emission-trading schemes, pressure from competitors, the nature of the legal system, and carbon exposure (Luo & Tang, 2016). Figure 1 illustrates supply chain engagement’s role in carbon management. In the following subsections, supply chain engagement is clarified from the perspectives of both upstream (supplier) and downstream (customer) supply chains.

Supplier Engagement

The importance of engaging suppliers to improve companies’ sustainability performance has been noted in several previous studies (Sancha et al., 2016; Tidy et al., 2016). Even though it is difficult for companies to control suppliers, powerful buyers can serve as role models and set standards, thereby extending their suppliers’ engagement in sustainability efforts (Amaeshi et al., 2008). By using sustainable supply management practices, firms can influence and engage their suppliers (Kähkönen et al., 2018), and by building on collaborative relational practices, better outcomes can be expected in terms of relational rents and competitive advantages (Dyer & Singh, 1998; Sancha et al., 2019). Recently, the relational view has been expanded to explain not just economic, but also environmental and social benefits (Villena et al., 2021).

Supplier engagement programs that conduct emission allocation analyses along the supply chain are important tools in focal companies’ carbon management process (Tidy et al., 2016). The first-tier suppliers pass on a focal company’s sustainability requirements to second-tier suppliers (Wilhelm et al., 2016), and the integration of a first-tier supplier’s marketing and purchasing functions is essential in transferring sustainability further upstream in the supply chain. For a supplier, being able to show new sustainability initiatives in its offerings to customers and other stakeholders, such as earning a sustainability certificate, fosters even more supplier engagement (Foerstl et al., 2015). Wilhelm et al. (2016) found that lead firms (i.e., focal companies) play a primary agency role in incentivizing their first-tier suppliers to accept carbon management and act as agents for second-tier and other upstream suppliers.

Customer Engagement

Customer engagement is an interactive process that enables deep and meaningful relationships and interactions between a company and its customers (Hollebeek, 2013). Only a few extant studies have examined customer engagement in connection with sustainability or carbon management (Jarvis et al., 2017), and these generally have adopted consumer behavioral perspectives to analyze customers’ willingness to engage in sustainability initiatives (O’Brien et al., 2020). For example, Gössling et al. (2009) found that passengers are co-creators of environmental value through voluntary carbon offsets in the aviation industry, and O’Brien et al. (2015) found that Internet service providers’ engagement in corporate social responsibility programs enhances customers’ preferences. Jarvis et al. (2017) emphasized the social attributes and platforms through which customer engagement can be pursued and measured. According to a recent study by Chen and Ho (2019), suppliers’ high-level, pro-environmental practices increase sales if their customers have similar levels of environmental management. Thus, investing in environmental practices is not beneficial for suppliers if their customers are not doing the same, and gains can be achieved only if these customers value their suppliers’ efforts. It also has been found that suppliers can engage their customers and increase customers’ dependency in business through instrumental motives and international environmental policies (Peng et al., 2022). Thus, from a supplier perspective, engaging with customers in carbon management is essential and can improve business.

From a buyer perspective, to become a preferred customer in the eyes of a supplier requires deep engagement from the customer side and an understanding of suppliers’ expectations (Nollet et al., 2012). For example, in carbon management, shared goals regarding emission reduction and collaboration in the area of climate change strengthen customers’ commitment to relationships with their suppliers (Patrucco et al., 2020), i.e., customers’ openness in communication regarding goals and ideas to improve relationship performance in carbon management is essential for supply chain engagement.

Hypothesis Development

The present study’s objective is to examine the determinants and preconditions for focal companies’ supply chain engagement in carbon management. A focal company is positioned between its suppliers and customers (Seuring & Müller, 2008); therefore, it has a two-way perspective on carbon management. The reasons for carbon management can arise from moral motives and genuine concern for the environment (Paulraj et al., 2017). Value-driven, moral-based motivation for carbon management might be reflected in business strategy (Plambeck, 2012) if environmental awareness is based on company values, top management commitment, and genuine concern (Paulraj et al., 2017). Moral motives also are visible when companies wield strong influence on climate change-related public policy, as they view them as the right thing to do (Detomasi, 2015). Thus, moral motives in this study are reflected by business strategy and active influence in public policy on climate change. However, companies that operate in GHG-intensive industries are searching for compensating actions, e.g., carbon management in the supply chain, to avoid poor publicity or other negative consequences, interpreted here as an instrumental motive (Jira & Toffel, 2013). Recent studies have found that instrumental motives also affect customer engagement (Peng et al., 2022). Companies also have relational motives to implement carbon management because they might aim to comply with stakeholder norms, e.g., their customers’ expectations, or environmental activists’ demands (Paulraj et al., 2017). Environmental regulations’ impact on companies’ carbon management is an external pressure, thereby reflecting relational motive (Paulraj et al., 2017). In the following section, these features’ links to supply chain engagement are clarified, and justifications for the proposed hypotheses are presented.

Business Strategy

Companies with abundant financial resources and strong management capabilities are most likely to implement proactive environmental strategies (Russo & Fouts, 1997), which can improve companies’ financial performance (Clarkson et al., 2011; Golicic & Smith, 2013; Pullman et al., 2009). By being a first mover in a market to create a sustainable business, a company can enhance its market share and image, thereby influencing profit generation (Paulraj, 2011; Plambeck, 2012). Companies that proactively seek business opportunities in carbon management and do not focus solely on risk management can perform better (Elijido-Ten & Clarkson, 2019).

Business strategies coordinate and integrate activities of functional units within the company, and supply chain management is aligned with these strategies (Hesping & Schiele, 2015). Plambeck (2012) identified several ways that climate change can be incorporated into business strategies and supply chain management. First, companies can cut costs by using energy-efficient technologies and identifying and implementing energy-efficient projects with suppliers. Second, companies can increase their revenues by improving public relations and customers’ willingness to buy sustainable and energy-saving products. Companies also can increase supply chain efficiency by reducing the number of intermediaries and brokers with which they interact and instead communicate directly with lower-tier suppliers about environmental issues. Finally, horizontal collaboration with other multinational buyers can motivate suppliers to strive for fewer emissions. Integrating carbon management into powerful buyers’ business strategies adds pressure on suppliers in particular to retain their customers (Villena & Dhanorkar, 2020), whereas engaging customers in carbon management often is based on a customer’s commitment to their relationship with the supplier (Patrucco et al., 2020). Therefore, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

H1a

Companies that integrate climate change into their business strategies are more likely to engage suppliers, customers, and both suppliers and customers in carbon management than those that do not.

H1b

Integrating climate change into business strategies has a larger impact on engaging suppliers than customers.

Activity and Influence on Climate Change Public Policy

According to Detomasi (2015), active companies can influence governments’ public policy and collaborate with non-governmental organizations to create environmental standards. The motivation to influence public policy is not solely to reduce emissions because high standards can be significant entry barriers for new competitors (Detomasi, 2015). Companies with low GHG emissions are most active in seeking to influence public policy because of their competitive advantage, whereas companies with high GHG emissions are more likely to try and maintain the status quo (Delmas et al., 2016).

Companies must align their political activity with tangible carbon management efforts. If they do otherwise, the risk of being attacked for hypocrisy increases (Lyon et al., 2018). Hoover and Fafatas (2018) concluded that U.S. states’ political leanings influence companies’ willingness to disclose carbon emission information. Furthermore, participation in sector-level associations, taking part in public forums, and collaborating with nonprofit organizations all motivate firms to undertake proactive carbon management and share a common vision of the actions needed to reduce supply chain emissions (Backman et al., 2017). Recently, even corporate activism has been evolving, with calls for changes to policies regarding societal and environmental issues (Eilert & Nappier Cherup, 2020). A firm’s intensive political activity may turn into corporate activism to lower emissions in an industry. It also has been found that suppliers’ actions that aim to reduce carbon emissions benefit the whole supply chain more than customers’ actions (Lee & Park, 2020). Thus, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

H2a

Companies that are highly active in and wield strong influence on public policy on climate change are more likely to engage suppliers, customers, and both suppliers and customers in carbon management than those that are not.

H2b

Activity in and strong influence on climate change public policy have a larger impact on engaging suppliers than customers.

GHG intensity of the Sector

Firms that operate in a GHG-intensive sector are more likely to face public scrutiny over their environmental efforts (Marquis et al., 2016). Supplier or customer engagement in terms of monitoring or collaborative efforts is one form of compensation that companies can employ in response to public pressure (Golicic & Smith, 2013; Shevchenko et al., 2016). For companies under the greatest pressure, it is easier to implement compensatory actions than more radical GHG emissions-reducing ones (Shevchenko et al., 2016). In GHG-intensive sectors, managers utilize certain environmental actions to build a better reputation and maintain the company’s profitability (Cai et al., 2012). As a result, firms in GHG-intensive sectors tend to be more active in reporting their commitment to environmental practices by using transparency tools—e.g., green indices, green brands, and certifications—than other businesses (Conte et al., 2022).

Monitoring tools and external reporting on sustainability are more likely to be used among companies that make direct negative impacts on the environment (van Zanten & van Tulder, 2018). GHG-intensive companies in highly regulated industries have been found to use more carbon management measurements than those in industries that are less regulated under climate policy (Sakhel, 2017). It also has been found that companies in energy-intensive industries have implemented more efficient carbon management strategies to reduce emissions effectively than firms from other sectors (Lee, 2012). Therefore, we present the following hypothesis:

H3

Companies operating in a high GHG-intensive industry are more likely to engage suppliers, customers, and both suppliers and customers in carbon management than those that operate in less GHG-intensive industries.

Country-Level Features

Environmental regulation stringency differs among countries, creating varying levels of institutional pressures on companies to implement carbon management (van Zanten & van Tulder, 2018). Environmental regulation drives sustainable supply chain management practices, particularly if companies are proactive about regulatory compliance (Walker et al., 2008; Zeng et al., 2017). When studying companies that are relatively advanced in their sustainability, institutional pressure is connected to ensuring suppliers’ sustainability in terms of environmental compliance and sharing values and standards along the supply chain (Jira & Toffel, 2013; Tate et al., 2010).

Less-strict environmental regulations in less economically developed countries create business environments in which customer pressure for carbon management is lower, and firms do not view supplier or customer engagement in carbon management as a business priority (Tumpa et al., 2019). Even if global buyers are driving voluntary engagement in carbon management, their power becomes weaker at the subcontracting stage in the context of supply chains in developing countries (Soundararajan & Brown, 2016). Small subcontractors lack the institutional pressure, skills, and financial resources to implement environmental initiatives, and their intermediaries might be lenient with non-compliance to maintain mutual trust (Soundararajan & Brown, 2016). Zhu et al. (2013) demonstrated that Chinese manufacturers were less likely to adopt practices that required some level of cooperation with either suppliers or customers concerning environmental regulation pressure. Based on these mixed findings, the present study proposes the following hypothesis:

H4

Companies operating in countries with high economic welfare and stringent environmental regulations are more likely to engage suppliers, customers, and both suppliers and customers in carbon management than those operating in developing countries with less stringent environmental regulations.

Methodology

The aim of this study is to examine determinants of supply chain engagement in companies’ carbon management. Furthermore, we also examine whether engagement is more influential upstream than downstream in the supply chain. To be able to evaluate the effects of the hypothesized determinants of engagement, a quantitative approach is chosen. Like Creswell (2014) has stated, quantitative methods are suitable for empirical studies that examine drivers’ impact on an outcome. Both multinomial and ordinal logistic regression analyses were used to test the hypotheses.

This study’s data were collected from several sources. The carbon management data came from the CDP’s supply chain program. Altogether, 345 firms from 31 countries were included, with 38% from the United States, 12% from the United Kingdom, 10% from Japan, and 40% from other countries. The companies participating in the CDP’s supply chain program can use it to capture their key suppliers’ carbon-related information (Carbon Disclosure Project 2017, 2018). Previously, although CDP data are used in studies regarding climate change (e.g., Dahlmann et al., 2019), only a few studies used CDP data in the supply chain context (e.g., Blanco, 2021; Jira & Toffel, 2013; Villena & Dhanorkar, 2020). Other data sources used in this study include the Thomson Reuters Fundamentals and Worldscope databases, currently provided through the Refinitiv Eikon database, the World Bank’s DataBank, and the World Economic Forum (2014).

Variables

Dependent Variables

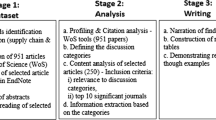

The first dependent variable based on the CDP data, Engagement, captures whether a company engages its suppliers, customers, or both in carbon management. The variable is a nominal categorical variable with four categories (see Table 1 for more details) and is used as the dependent variable in the multinomial logistic regression estimations. Two other dependent variables—Supplier engagement and Customer engagement—also were generated based on the CDP data, which include a text portion in which companies describe their supplier and/or customer engagement. Based on the previous literature and following Dyer and Singh (1998) and Klassen and Vachon (2003), we created a coding framework for the content analysis to identify activities, strategies, and practices that belong to either the monitoring category or the collaboration category (see Appendix 1). In accordance with previous studies, we defined monitoring as arm’s length, lower- or basic-level activities and collaboration as activities conducted at a more mature level and aimed toward joint benefits (e.g., Gualandris et al., 2015; Klassen & Vachon, 2003; Vachon & Klassen, 2006, 2008). Two researchers analyzed and coded the text data by using the agreed-upon framework and keywords. To resolve differences between their efforts, a third researcher participated in the process. As suggested by Dahlmann and Roehrich (2019), who used a similar process with the same CDP material, our data analysis process went through multiple iterations to ensure correctness and consistency. Supplier engagement and Customer engagement resulting from this content analysis are ordinal categorical variables with a rising engagement level: For both variables, “No engagement” depicts the lowest engagement level, “Monitoring” depicts basic-level engagement activities, and “Collaboration” depicts the highest engagement level. These variables were used as dependent variables in ordinal logistic regression analyses.

Explanatory Variables

The first explanatory variable originating from the CDP data is a dichotomous variable, Strategy, coded 1 when climate change is integrated into the company’s business strategy and 0 otherwise. The second explanatory CDP variable, Influence, is also a dichotomous variable, associated with whether a company engages in any activities that either directly or indirectly could influence public policy on climate change. These variables are associated with Hypotheses 1 and 2 and are described in more detail in Table 1.

An industry’s GHG intensity (GHGint) is measured through average carbon dioxide (CO2) intensity within the Global Industry Classification Standard (GICS) sectors. Company-level CO2 intensities from the Refinitiv Eikon database were retrieved to calculate the variable (see Table 1). As for country-level variables, GDP per capita came from the World Bank’s DataBank. Finally, following Grauel and Gotthardt (2017), a country’s environmental governance level (Envgov) was calculated as an average of two items from the World Economic Forum’s (2014) Executive Opinion Survey: the stringency and enforcement levels of a given country’s environmental regulations. This variable is based on survey data from 2013 and 2014, and was used as a proxy for Envgov in 2015 due to the high persistence found in such institutional measures (as far as we are aware, data for 2015 were unavailable). These variables also are detailed in Table 1.

Control Variables

Several studies have demonstrated that a company’s size and financial performance influence its carbon management activity. Large companies have more money and other resources to invest in environmentally friendly technologies and sustainable supply chain management practices (Zhu et al., 2008). Large companies also experience greater pressure from the public and stakeholders on carbon disclosure and emissions reductions; thus, they are more incentivized to adopt carbon management systems and make compensations (Luo & Tang, 2016; Shevchenko et al., 2016). Reputational risks due to any environmental misconduct along the supply chain (Lintukangas et al., 2016) and social and economic pressure drive large companies to engage their supply chains in carbon management (Luo et al., 2012). Therefore, companies’ size and financial status were included as control variables in the analyses. Company-level financial data come from the Thomson Reuters Fundamentals and Worldscope databases, currently provided through the Refinitiv Eikon database. Company size was measured by the number of Employees and financial performance by return on assets (ROA). Due to data availability and to increase the sample size, fiscal data, rather than calendar year data, were collected for these variables.

Depending on data availability for the model under estimation, the number of companies included in the analysis varied, from 337 to 345. The data for the dependent engagement variables came from 2016, while all explanatory variables were lagged by one year to address potential simultaneity. Furthermore, Employees and GDP per capita were logged. Summary statistics for the observations used in the analysis are presented in Table 2, while the correlation coefficients appear in Table 3.

Estimation Methods

Our dependent variables are nominal and ordinal in nature; thus, we used two estimation methods: multinomial logistic regression for the nominal Engagement variable and ordinal logistic regression for the ordinal Supplier engagement and Customer engagement variables. If the dependent variable is ordinal, it is more parsimonious and interpretable to use an estimation method that does not ignore the response categories’ ordering (e.g., Williams, 2016). However, if no natural ordering exists for the response categories, multinomial logistic regression must be used. The Stata/SE 16.1 software package and maximum likelihood estimation were used to fit all the models.

Multinomial Logistic Regression

The dependent variable Engagement is a nominal variable with four response categories without natural ordering (see Table 1). In this case, multinomial logistic regression (Greene, 2008, pp. 841–847; Verbeek, 2012, pp. 228–231) allowed us to evaluate the explanatory variables’ impact on which value chain partners (suppliers, customers, or both) are more likely to engage in carbon management. Sluis and De Giovanni (2016) previously used multinomial logistic regression analysis in a relatively similar context. Multinomial logistic regression analysis can be performed using maximum likelihood estimation, which is based on finding the values of the parameters to be estimated that maximizing the log-likelihood function. A crucial assumption of multinomial logistic regression analysis is that the relative risk ratio between any pair of outcome categories does not depend on the other alternatives available. This assumption is called the independence of irrelevant alternatives (IIA). In accordance with Long and Freese’s (2006, pp. 243–246) recommendation, we relied on a seemingly unrelated estimation-based Hausman test to evaluate this assumption.

Ordinal Logistic Regression

If the response categories of a dependent variable are inherently ordinal, but depict only ranking, an ordinal response model can be used to account for the nature of the variable (Greene, 2008, pp. 831–841; Verbeek, 2012, pp. 221–222). Our dependent variables, Supplier engagement and Customer engagement, are ordinal because their categories illustrate a rising engagement level, from no engagement to collaboration. Again, estimation was done using maximum likelihood. Two alternatives are possible, depending on the assumptions made regarding error terms: In ordinal logistic regression, the error terms are assumed to follow logistic distribution, while ordinal probit regression assumes that they follow standard normal distribution. We chose to use ordinal logistic regression, which social scientists use often (Hill et al., 2018, p. 711). If the ordinal logistic model’s parallel-line assumptions are met, all coefficients apart from the intercepts should be equal across different logistic regressions, subject to sampling variability (Williams, 2016).

Results

Engagement in Carbon Management: Multinomial Logistic Regression Results

The multinomial logistic regression analysis results are provided in Table 4. The reference category is Category 0, in which the company does not engage either suppliers or buyers in its carbon management, i.e., no engagement. Model (1) includes only company-level explanatory variables, Model (2) adds the industry-level explanatory variable, and Model (3) includes company-, industry-, and country-level explanatory variables. The model diagnostics indicate that at least one of the regression coefficients in the models differs from zero. Moreover, the Akaike information criterion (AIC) implies that Model (3) should be chosen, while the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) indicates that Model (1) is preferable. Due to these contradictory results concerning model selection, we chose to discuss all three models.

As indicated above, the IIA assumption should hold for multinomial logistic regression results to be reliable. We tested the assumption using Stata’s seemingly unrelated estimation-based Hausman test. A limitation of this test is that it cannot be performed with robust standard errors; thus, we estimated the models without robust standard errors to perform the test. According to the results, the null hypothesis of other alternatives’ independence was not rejected in any of the models.

Engaging suppliers vs. engaging neither suppliers nor customers: First, compared with engaging neither suppliers nor customers in carbon management, integrating climate change into the company’s business strategy increases the probability of engaging suppliers in carbon management. The relative risk ratio of Strategy ranges between 6.0 and 6.1, indicating that integrating climate change into a business strategy is expected to increase the relative chances of engaging suppliers in carbon management by a factor of around 6, compared with engaging neither suppliers nor customers, given that the other explanatory variables in the model are held constant.

Second, engaging in activities that could influence climate change public policy also increases the probability of engaging suppliers in carbon management. The relative risk ratio of Influence ranges between 5.6 and 6.0. Third, larger companies (measured by number of Employees) are more likely to engage their suppliers in carbon management. These results are robust to all model specifications presented in Table 4. However, ROA, the variable measuring corporate financial performance, is statistically insignificant in all models, even at the 10% risk level, thereby suggesting that financial performance is not an important determinant of whether companies engage their suppliers in carbon management. The same applies to industry-level and country-level explanatory variables, which remain statistically insignificant in all models.

Engaging customers vs. engaging neither suppliers nor customers: Compared with engaging neither suppliers nor customers in carbon management, engaging in activities that could influence public policy on climate change also increases the probability of engaging customers in carbon management, but the effect is weaker than in the case of suppliers. Here, the relative risk ratio ranges between 2.9 and 4.6. Interestingly, integrating climate change into the company’s business strategy appears to play a less important role with regard to engaging customers over suppliers in carbon management, while the role of company size is reduced even further. Corporate financial performance and industry- and country-level explanatory variables continue to remain statistically insignificant, even at the 10% level, in all models.

Engaging suppliers and customers vs. engaging neither suppliers nor customers: As for engaging both suppliers and customers in carbon management, the roles of climate change strategy, influencing public policy, and company size are highlighted. The relative risk ratios range from 7.7 to 8.6 (Strategy), 6.5 to 7.4 (Influence), and 2.0 to 2.3 (Employees). However, the most important change relative to the other dependent variable categories is that the company’s sector average for CO2 intensity (GHGint) appears to increase the probability of engaging both suppliers and customers in carbon management.

Including industry dummies based on GICS classification as control variables in the models resulted in problems with too few observations in some cross-tabulation cells between the industries and Engagement, which undermined the estimations’ reliability. Thus, we had to drop industry dummies from the models. The results’ robustness was tested by using two other measures of corporate financial performance instead of ROA. The main results are robust to using Profitability (calculated by dividing earnings before interest and taxes by sales) and Slack (calculated by dividing cash by sales) as measures of corporate financial performance. Considering that the IIA assumption is impossible to test reliably, we also performed robustness tests by using logistic regression analysis (see Appendix 2 for the results). The results support those of the multinomial regressions.

Differences Between Supplier and Customer Engagement: Ordinal Logistic Regression Results

The results from the ordinal logistic regression analysis for supplier and customer engagement are presented in Table 5. As in Table 4, Model (1) includes only company-level explanatory variables, Model (2) adds the industry-level explanatory variable, and Model (3) includes company-, industry-, and country-level explanatory variables. Columns 2–4 in Table 5 provide the results for supplier engagement, and Columns 5–7 provide the results for customer engagement. The Wald test results at the bottom of the table indicate that at least one of the regression coefficients in the models differs from zero.

The results indicate that integrating climate change into a company’s business strategy and becoming actively involved in public policy on climate change strongly impact supplier engagement level positively, but not customer engagement level. Both explanatory variables are statistically significant, at least at the 5% level, in all three supplier engagement models, whereas the customer engagement models offer considerably less-robust evidence of the explanatory variables’ statistical significance. Moreover, when statistically significant, the variables’ coefficients are also smaller in the customer engagement models than in the supplier engagement models. However, company size appears to affect both supplier and customer engagement.

The results also indicate that the higher the GHG intensity of a company’s industry, the higher that company’s supplier engagement level; however, the variable does not appear to affect customer engagement level. Finally, and unlike the multinomial logistic regression results discussed above, ROA also appears to increase supplier engagement level, and the country-level explanatory variables continue to be statistically insignificant in these models.

The ordinal logit results’ robustness was tested using Profitability and Slack as measures of corporate financial performance. Strategy and Influence continue to impact supplier engagement level positively, but not customer engagement level, whereas company size appears to boost both supplier and customer engagement. However, the GHG intensity of the company’s sector does not appear to impact supplier engagement in these models, while the effect of corporate financial performance appears to depend on the financial performance measure: Like ROA, Profitability appears to increase supplier engagement, but Slack does not.

Stata’s ologit command is based on a parallel regression assumption of the ordinal logistic model. The Brant test sometimes is used to determine whether the assumption holds (Long & Freese, 2014). Brant test results provided at the bottom of Table 5 indicate that the parallel regression assumption was violated at the 5% risk level in Models 1 and 2 for supplier engagement and Model 3 for customer engagement. We also estimated these models through generalized ordinal logit using Williams’ (2006, 2016) Stata gologit2 command. The results from the partial proportional odds estimations, in which some of the coefficients are allowed to differ between response categories, support the main implications (see Appendices 3 and 4).

Discussion

Theoretical implications

The engagement of all supply chain actors in carbon management is necessary to fight climate change. We found that companies with moral motives are more likely to engage their suppliers and customers in carbon management than companies that lack moral motives (H1a and H2a). More specifically, companies that integrate climate change into their business strategies are more likely to engage their suppliers and customers in carbon management than those that do not (H1a). Our multinomial logistic regression results support this argument in all three categories––suppliers alone, customers alone, and both suppliers and customers––and are in line with studies by Plambeck (2012) and Elijido-Ten and Clarkson (2019). Similarly, H2a was supported: Firms active in influencing public policy on climate change are more likely to engage their supply chain in carbon management (Backman et al., 2017; Hoover & Fafatas, 2018). Detomasi (2015) found that active companies can influence public policy to create environmental standards, and our results demonstrate further that these companies are also active in influencing their supply chains’ carbon management.

Our study contributes to the sustainable supply chain management field (Paulraj et al., 2017; Sharfman et al., 2009) by showing that a focal firm’s moral motives make a stronger impact on supplier engagement than customer engagement. This contribution is based on results from ordinal logistic regression analyses related to H1a and H1b. First, integrating climate change into a business strategy makes a larger impact when engaging suppliers compared with customers (H1b). This is in line with Villena and Dhanorkar (2020), who found that integration of carbon management into powerful buyers’ business strategies adds pressure, particularly on suppliers, to reduce GHG emissions. Second, we found that being active in influencing public policy on climate change makes a greater impact in engaging suppliers than with customers (H2b).

All in all, it appears that moral motives make a stronger impact on supplier engagement because a large proportion of companies’ GHG emissions can be traced outside of the firms’ boundaries to their suppliers, incentivizing companies to try to affect their suppliers’ emissions (Kagawa et al., 2015; Plambeck, 2012; Tidy et al., 2016). Suppliers’ carbon management actions also would strengthen focal companies’ carbon management efforts automatically. Companies with moral motives are value-driven and push for actions to counter climate change, and if they engage their first-tier suppliers on carbon management, the results along the entire supply chain can be promising. First-tier suppliers may have a relational motive to leverage sustainability requirements; thus, they aim to comply with social norms and achieve legitimacy within their supply chain to gain long-term relational rents, as Paulraj et al. (2017) suggested. Through proactive supply chain engagement and joint deployment of resources and technologies to reduce carbon emissions, long-term benefits and relational rents can be achieved (Dyer & Singh, 1998; Villena et al., 2021). Consequently, suppliers’ carbon management actions benefit the whole supply chain more than customers’ actions (Lee & Park, 2020; Wilhelm et al., 2016).

Moreover, our ordinal logistic regression results confirm that companies with moral motives are more likely to collaborate and seek higher-level engagement with their suppliers, rather than just monitor them. Incentivizing suppliers via collaborative actions increases suppliers’ willingness to commit to sustainability actions (Gualandris & Kalchschmidt, 2014; Jira & Toffel, 2013), and companies with moral motives truly are seeking a significant reduction in GHG emissions.

Previous research (Paulraj et al., 2017) has found moral and relational motives to be stronger drivers of carbon management in the supply chain than instrumental motives. Our results support this because although we found industry-level GHG intensity to be a significant determinant of supply chain engagement (supporting H3), business strategies (H1) and political activity (H2) were considerably stronger determinants. We found that GHG intensity also increased customer engagement, thereby supporting a recent Peng et al. (2022) study that indicated instrumental motives affect customer engagement. Consequently, both supplier and customer engagement in the disclosure procedure help reduce emissions’ total impact in supply chains––not just supplier engagement, as Jira and Toffel (2013) and Luo et al. (2012) also reported.

Our results also underscore that companies in the most GHG-intensive industries not only monitor their emissions, but also actively collaborate with their suppliers to offset emissions. The higher the GHG intensity of a company’s industry, the higher the probability that the company has chosen to collaborate to engage suppliers. We found that companies operating in GHG-intensive sectors have instrumental motives for engagement and use it as compensating actions, providing temporary relief from stakeholder pressure (Shevchenko et al., 2016). These principally instrumental motives are reasons why companies in GHG-intensive sectors are more likely to engage both suppliers and customers in their supply chain.

Our analysis does not support arguments regarding relational motives’ effects (H4) for firms operating in highly developed economies with more stringent environmental regulation (e.g., Sakhel, 2017; Tumpa et al., 2019). While it previously has been reported that more stringent environmental regulation increases GHG emission information sharing between suppliers and buyers, and that firms in highly regulated industries use more carbon management measures (Zeng et al., 2017), our results indicate that institutional pressures do not significantly affect supply chain engagement. Focal companies, rather than environmental regulation or the country’s welfare level, drive supply chain engagement for strategic reasons on a voluntary basis.

We assumed that large companies are more likely to engage their supply chains in carbon management than small companies (e.g., Luo & Tang, 2016; Shevchenko et al., 2016), so we included company size as a control variable in our analysis. In line with Luo and Tang (2016), Shevchenko et al. (2016), and many others, our results show that large companies engage both their suppliers and their customers in carbon management. This result is unsurprising because large companies have more money and other resources, and many studies (e.g., Lintukangas et al., 2016) have shown that firm size correlates with sustainability efforts and performance. We also suggested that companies with good financial performance are more likely to engage supply chain members in carbon management than companies with poor financial performance. A company’s good financial status previously has been reported to be a significant factor in sustainable supply chain studies (e.g., Zhu et al., 2008). However, according to our results, good financial performance did not indicate either supplier or customer engagement. The reason for this conflicting result could be that the impact of corporate financial performance varies in the 28 different countries in our sample, so this issue should be considered in future studies and examined more carefully.

Managerial Implications

Companies with moral motives to reduce emissions must adopt effective and feasible carbon management practices that promote collaboration within supply chains because with collaboration-based actions, better long-term results can be achieved. Engaging suppliers and customers on carbon management reduces vulnerability to climate-related risks and increases resilience and adaptability in supply chains in general, which is highly critical for companies in the current business environment, awash in several crises. In particular, companies operating in GHG-intensive industries need to realize that both supplier and customer engagement are significant. To elicit more transparent information sharing and behavior from suppliers, a larger number of buyers should request that suppliers disclose carbon and climate change information because suppliers’ willingness to share such information increases when several buyers request it, and when they use that information as a buying criterion. Moreover, utilizing their relational capabilities and collaborations, buyers who operate based on moral motives can reduce the opportunism of actors in supply chains and increase engagement toward disclosure, which ultimately will lead to better results in carbon management. Whether the buyer’s motive is instrumental, relational, or moral when engaging suppliers in carbon management, suppliers also will experience benefits. For example, by committing to and engaging in reducing emissions, suppliers may appear to be potential partners for long-term relationships, which can be a decisive factor in supplier selection and offer a competitive advantage to supplier firms. Recognizing the company’s position as a focal company in a supply chain simplifies carbon management and eases disclosure processes in both the downstream and upstream supply chains.

Conclusions

To enhance understanding of how suppliers and customers could be engaged in carbon management, we provided evidence that supports companies’ moral and instrumental motives. Not only do moral motives––e.g., integrating climate change into the company’s business strategy and being active in influencing climate change public policy––appear to be particularly important, but also instrumental motives––e.g., operating in a GHG-intensive sector––in increasing the probability of engaging suppliers and customers in carbon management. Moreover, we show that engagement actions’ impact is stronger in the upstream than in the downstream supply chain, amplifying the importance of supplier engagement in carbon management to ensure supply chains’ sustainability. We conceptualized supply chain engagement by including both suppliers and customers, thereby contributing to the supply chain literature by offering a wider scope than previous studies. By using text-based content analysis from the CDP data and applying the relational view as a theoretical lens, we developed categories to measure engagement more accurately. Our study further contributes to extant supply chain management research by exploiting multinomial and ordinal logistic regression estimation methods using data from the CDP’s supply chain program, and by elevating the data further by complementing it with data from other databases. Moreover, this study broadens the view of business ethics from the sustainability perspective by demonstrating the importance of a focal firm’s motives in engaging supply chain actors to reduce emissions.

However, despite our contributions, this research has some limitations. We focused on the CDP supply chain program, but the CDP offers other programs that could be used in future studies. Using multinomial and ordinal logistic regression as the estimation methods also placed other restrictions on the explanatory variables we could use in our models. Moreover, further research could examine the effects of focal companies’ technological capabilities in engaging their suppliers and buyers in carbon management because reducing emissions requires changes in both processes and technologies. In this study, we concentrated on a focal company and its suppliers and customers, but it would be valuable to determine whether suppliers’ suppliers in the lower tiers also could be investigated. This would widen the supply chain perspective even more and provide empirical insights into carbon management and sustainability in multi-tier supply chains and networks. Moreover, because the CDP data are limited to disclosure and reporting only, examining specific factors, e.g., spending and product categories within supply chain engagement, was not possible. We also acknowledge that omitted-variable bias might affect our results. Such omitted variables include, among other things, company management characteristics (Ben-Amar & McIlkenny, 2015), mimetic and environmental NGO pressure (Villena & Dhanorkar, 2020), and the supply chain’s structure (Gualandris et al., 2021). Accordingly, these variables’ role in engaging suppliers and customers in carbon management would be an interesting topic for further research.

Supply chain engagement is an integral part of a firm’s strategic sustainability management efforts to reduce GHG emissions, mitigate climate-related risks, and increase resilience in supply chains. By engaging suppliers and customers in carbon management, a focal firm can respond to the challenges arising from climate change and mitigate the potentially devastating social and economic impacts that global warming may cause in the future.

References

Ahi, P., & Searcy, C. (2013). A comparative literature analysis of definitions for green and sustainable supply chain management. Journal of Cleaner Production, 52, 329–341.

Amaeshi, K. M., Osuji, O. K., & Nnodim, P. (2008). Corporate social responsibility in supply chains of global brands: A boundaryless responsibility? Clarifications, exceptions and implications. Journal of Business Ethics, 81(1), 223–234.

Backman, C. A., Verbeke, A., & Schulz, R. A. (2017). The drivers of corporate climate change strategies and public policy. Business & Society, 56(4), 545–575.

Ben-Amar, W., & McIlkenny, P. (2015). Board effectiveness and the voluntary disclosure of climate change information. Business Strategy and the Environment, 24(8), 704–719.

Blanco, C. (2021). Supply chain carbon footprinting and climate change disclosures of global firms. Production and Operations Management, 30(9), 3143–3160.

Blanco, C., Caro, F., & Corbett, C. J. (2016). The state of supply chain carbon footprinting: Analysis of CDP disclosures by US firms. Journal of Cleaner Production, 135, 1189–1197.

Blanco, C., Caro, F., & Corbett, C. J. (2017). An inside perspective on carbon disclosure. Business Horizons, 60(5), 635–646.

Blome, C., Paulraj, A., & Schuetz, K. (2014). Supply chain collaboration and sustainability: A profile deviation analysis. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 34(5), 639–663.

Cai, Y., Jo, H., & Pan, C. (2012). Doing well while doing bad? CSR in controversial industry sectors. Journal of Business Ethics, 108(4), 467–480.

Carbon Disclosure Project: Supply chain database and survey questionnaires. (2017). Carbon disclosure project. Retrieved from https://www.cdp.net/en.

Carbon Trust. (2018). Carbon disclosure project: Cascading commitments: Driving ambitious action through supply chain engagement. CDP supply chain report.

Chen, C., & Ho, H. (2019). Who pays you to be green? How customers’ environmental practices affect the sales benefits of suppliers’ environmental practices. Journal of Operations Management, 65(4), 333–352.

Choi, T. Y., & Krause, D. R. (2006). The supply base and its complexity: Implications for transaction costs, risks, responsiveness, and innovation. Journal of Operations Management, 24(5), 637–652.

Clarkson, P. M., Li, Y., Richardson, G. D., & Vasvari, F. P. (2011). Does it really pay to be green? Determinants and consequences of proactive environmental strategies. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 30(2), 122–144.

Conte, F., Sardanelli, D., Vollero, A., & Siano, A. (2022). CSR signaling in controversial and noncontroversial industries: CSR policies, governance structures, and transparency tools. European Management Journal. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2021.12.003

Corbett, C. J. (2006). Global diffusion of ISO 9000 certification through supply chains. Manufacturing and Service Operations Management, 8(4), 330–350.

Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (4th ed.). Sage Publications.

Dahlmann, F., Branicki, L., & Brammer, S. (2019). Managing carbon aspirations: The influence of corporate climate change targets on environmental performance. Journal of Business Ethics, 158(1), 1–24.

Dahlmann, F., & Roehrich, J. K. (2019). Sustainable supply chain management and partner engagement to manage climate change information. Business Strategy and the Environment, 28(8), 1632–1647.

Delmas, M., Lim, J., & Nairn-Birch, N. (2016). Corporate environmental performance and lobbying. Academy of Management Discoveries, 2(2), 175–197.

Detomasi, D. (2015). The multinational corporation as a political actor: ‘Varieties of capitalism’ revisited. Journal of Business Ethics, 128(3), 685–700.

Dhanda, K. K., & Hartman, L. P. (2011). The ethics of carbon neutrality: A critical examination of voluntary carbon offset providers. Journal of Business Ethics, 100(1), 119–149.

Dyer, J. H., & Singh, H. (1998). The relational view: Cooperative strategy and sources of interorganizational competitive advantage. Academy of Management Review, 23(4), 660–679.

Eilert, M., & Nappier Cherup, A. (2020). The activist company: Examining a company’s pursuit of societal change through corporate activism using an institutional theoretical lens. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 39(4), 461–476.

Elijido-Ten, E. O., & Clarkson, P. (2019). Going beyond climate change risk management: Insights from the world’s largest most sustainable corporations. Journal of Business Ethics, 157(4), 1067–1089.

Foerstl, K., Azadegan, A., Leppelt, T., & Hartmann, E. (2015). Drivers of supplier sustainability: Moving beyond compliance to commitment. Journal of Supply Chain Management, 51(1), 67–92.

Gimenez, C., & Sierra, V. (2013). Sustainable supply chains: Governance mechanisms to greening suppliers. Journal of Business Ethics, 116(1), 189–203.

Golicic, S. L., & Smith, C. D. (2013). A meta-analysis of environmentally sustainable supply chain management practices and firm performance. Journal of Supply Chain Management, 49(2), 78–95.

Gössling, S., Haglund, L., Kallgren, H., Revahl, M., & Hultman, J. (2009). Swedish air travellers and voluntary carbon offsets: Towards the co-creation of environmental value? Current Issues in Tourism, 12(1), 1–19.

Grauel, J., & Gotthardt, D. (2017). Carbon disclosure, freedom and democracy. Social Responsibility Journal, 13(3), 428–456.

Greene, W. H. (2008). Econometric analysis (6th ed.). Pearson Prentice Hall.

Gualandris, J., & Kalchschmidt, M. (2014). Customer pressure and innovativeness: Their role in sustainable supply chain management. Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management, 20(2), 92–103.

Gualandris, J., Klassen, R. D., Vachon, S., & Kalchschmidt, M. (2015). Sustainable evaluation and verification in supply chains: Aligning and leveraging accountability to stakeholders. Journal of Operations Management, 38(1), 1–13.

Gualandris, J., Longoni, A., Luzzini, D., & Pagell, M. (2021). The association between supply chain structure and transparency: A large-scale empirical study. Journal of Operations Management, 67(7), 803–827.

Hesping, F. H., & Schiele, H. (2015). Purchasing strategy development: A multi-level review. Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management, 21(2), 138–150.

Hill, R. C., Griffiths, W. E., & Lim, G. C. (2018). Principles of econometrics (5th ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

Hollebeek, L. D. (2013). The customer engagement/value interface: An exploratory investigation. Australasian Marketing Journal, 21(1), 17–24.

Hoover, S., & Fafatas, S. (2018). Political environment and voluntary disclosure in the U.S.: Evidence from the carbon disclosure project. Journal of Public Affairs, 18(4), e1637.

IPCC, 2022: Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E.S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem, B. Rama (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press. In Press. Retrieved Mar 26, 2022 from https://report.ipcc.ch/ar6wg2/pdf/IPCC_AR6_WGII_SummaryForPolicymakers.pdf.

Jarvis, W., Ouschan, R., Burton, H. J., Soutar, G., & O’Brien, I. M. (2017). Customer engagement in CSR: A utility theory model with moderating variables. Journal of Service Theory and Practice, 27(4), 833–853.

Jira, C., & Toffel, M. W. (2013). Engaging supply chains in climate change. Manufacturing & Service Operations Management, 15(4), 559–577.

Kagawa, S., Suh, S., Hubacek, K., Wiedmann, T., Nansai, K., & Minx, J. (2015). CO 2 emission clusters within global supply chain networks: Implications for climate change mitigation. Global Environmental Change, 35, 486–496.

Kähkönen, A.-K., Lintukangas, K., & Hallikas, J. (2018). Sustainable supply management practices: Making a difference in a firm’s sustainability performance. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 23(6), 518–530.

Klassen, R. D., & Vachon, S. (2003). Collaboration and evaluation in the supply chain: The impact on plant-level environmental investment. Production and Operations Management, 12(3), 336–352.

Lee, S. (2012). Corporate carbon strategies in responding climate change. Business Strategy and the Environment, 21, 33–48.

Lee, S., & Park, S. J. (2020). Who should lead carbon emissions reductions? Upstream vs downstream firms. International Journal of Production Economics, 230, 107790.

Lintukangas, K., Kähkönen, A.-K., & Ritala, P. (2016). Supply risks as drivers of green supply management adoption. Journal of Cleaner Production, 112, 1901–1909.

Long, S., & Freese, J. (2006). Regression models for categorical dependent variables using stata (2nd ed.). Stata Press.

Long, S., & Freese, J. (2014). Regression models for categorical dependent variables using stata (3rd ed.). Stata Press.

Luo, L., Lan, Y.-C., & Tang, Q. (2012). Corporate incentives to disclose carbon information: Evidence from the CDP global 500 report. Journal of International Financial Management & Accounting, 23(2), 93–120.

Luo, L., & Tang, Q. (2016). Determinants of the quality of corporate carbon management systems: An international study. The International Journal of Accounting, 51(2), 275–305.

Lyon, T. P., Delmas, M. A., Maxwell, J. W., Bansal, P., Chiroleu-Assouline, M., Crifo, P., Durand, R., Gond, J.-P., King, A., Lenox, M., Toffel, M., Vogel, D., & Wijen, F. (2018). CSR needs CPR: Corporate sustainability and politics. California Management Review, 60(4), 5–24.

Marquis, C., Toffel, M. W., & Zhou, Y. (2016). Scrutiny, norms, and selective disclosure: A global study of greenwashing. Organization Science, 27(2), 483–504.

Montiel, I. (2008). Corporate social responsibility and corporate sustainability. Organization & Environment, 21(3), 245–269.

Nollet, J., Rebolledo, C., & Popel, V. (2012). Becoming a preferred customer one step at a time. Industrial Marketing Management, 41(8), 1186–1193.

O’Brien, I. M., Jarvis, W., & Soutar, G. N. (2015). Integrating social issues and customer engagement to drive loyalty in a service organisation. Journal of Services Marketing, 29(6/7), 547–559.

O’Brien, I. M., Ouschan, R., Jarvis, W., & Soutar, G. N. (2020). Drivers and relationship benefits of customer willingness to engage in CSR initiatives. Journal of Service Theory and Practice, 30(1), 5–29.

Patrucco, A. S., Moretto, A., Luzzini, D., & Glas, A. H. (2020). Obtaining supplier commitment: Antecedents and performance outcomes. International Journal of Production Economics, 220, 107449.

Paulraj, A. (2011). Understanding the relationship between internal resources and capabilities, sustainable supply management and organizational sustainability. Journal of Supply Chain Management, 47(1), 19–37.

Paulraj, A., Chen, I. J., & Blome, C. (2017). Motives and performance outcomes of sustainable supply chain management practices: A multi-theoretical perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 145(2), 239–258.

Peng, Y., Zhang, X., van Donk, D. P., & Wang, C. (2022). How can suppliers increase their buyers’ CSR engagement: The role of internal and relational factors. International Journal of Operations and Production Management, 42(2), 206–229.

Plambeck, E. L. (2012). Reducing greenhouse gas emissions through operations and supply chain management. Energy Economics, 34, S64–S74.

Pullman, M. E., Maloni, M. J., & Carter, C. R. (2009). Food for thought: Social versus environmental sustainability practices and performance outcomes. Journal of Supply Chain Management, 45(4), 38–54.

Reinhardt, F. L., Stavins, R. N., & Vietor, R. H. K. (2008). Corporate social responsibility through an economic lens. Review of Environmental Economics and Policy, 2(2), 219–239.

Russo, M. V., & Fouts, P. A. (1997). A resource-based perspective on corporate environmental performance and profitability. Academy of Management Journal, 40(3), 534–559.

Sakhel, A. (2017). Corporate climate risk management: Are European companies prepared? Journal of Cleaner Production, 165, 103–118.

Sancha, C., Wong, C. W. Y., & Gimenez, C. (2019). Do dependent suppliers benefit from buying firms’ sustainability practices? Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management, 25(4), 100542.

Sancha, C., Wong, C. W. Y., & Gimenez Thomsen, C. (2016). Buyer–supplier relationships on environmental issues: A contingency perspective. Journal of Cleaner Production, 112, 1849–1860.

Sarkis, J., Gonzalez-Torre, P., & Adenso-Diaz, B. (2010). Stakeholder pressure and the adoption of environmental practices: The mediating effect of training. Journal of Operations Management, 28(2), 163–176.

Scope-3. (2011). Corporate value chain (Scope 3) accounting and reporting standard. Retrieved Mar 17, 2022 from https://ghgprotocol.org/standards/scope-3-standard.

Seuring, S., & Müller, M. (2008). From a literature review to a conceptual framework for sustainable supply chain management. Journal of Cleaner Production, 16(15), 1699–1710.

Sharfman, M. P., Shaft, T. M., & Anex, R. P. (2009). The road to cooperative supply-chain environmental management: Trust and uncertainty among pro-active firms. Business Strategy and the Environment, 18(1), 1–13.

Shevchenko, A., Moren, L., & Pagell, M. (2016). Why firms delay reaching true sustainability. Journal of Management Studies, 53(5), 911–935.

Sluis, S., & De Giovanni, P. (2016). The selection of contracts in supply chains: An empirical analysis. Journal of Operations Management, 41(1), 1–11.

Soundararajan, V., & Brown, J. A. (2016). Voluntary governance mechanisms in global supply chains: Beyond CSR to a stakeholder utility perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 134(1), 83–102.

Tang, Q., & Luo, L. (2014). Carbon management systems and carbon mitigation. Australian Accounting Review, 24(1), 84–98.

Tate, W. L., Ellram, L. M., & Kirchoff, J. F. (2010). Corporate social responsibility reports: A thematic analysis related to supply chain management. Journal of Supply Chain Management, 46(1), 19–44.

Tidy, M., Wang, X., & Hall, M. (2016). The role of Supplier Relationship Management in reducing Greenhouse Gas emissions from food supply chains: Supplier engagement in the UK supermarket sector. Journal of Cleaner Production, 112, 3294–3305.

Tumpa, T. J., Ali, S. M., Rahman, M. H., Paul, S. K., Chowdhury, P., & Rehman Khan, S. A. (2019). Barriers to green supply chain management: An emerging economy context. Journal of Cleaner Production, 236, 117617.

Vachon, S., & Klassen, R. D. (2006). Extending green practices across the supply chain. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 26(7), 795–821.

Vachon, S., & Klassen, R. D. (2008). Environmental management and manufacturing performance: The role of collaboration in the supply chain. International Journal of Production Economics, 111(2), 299–315.

van Zanten, J. A., & van Tulder, R. (2018). Multinational enterprises and the sustainable development goals: An institutional approach to corporate engagement. Journal of International Business Policy, 1(3–4), 208–233.

Verbeek, M. (2012). A guide to modern econometrics (4th ed.). John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Villena, V. H., & Dhanorkar, S. (2020). How institutional pressures and managerial incentives elicit carbon transparency in global supply chains. Journal of Operations Management, 66(6), 697–734.

Villena, V. H., Wilhelm, M., & Xiao, C. (2021). Untangling drivers for supplier environmental and social responsibility: An investigation in Philips Lighting’s Chinese supply chain. Journal of Operations Management, 67(4), 476–510.

Walker, H., Di Sisto, L., & McBain, D. (2008). Drivers and barriers to environmental supply chain management practices: Lessons from the public and private sectors. Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management, 14(1), 69–85.

Wilhelm, M. M., Blome, C., Bhakoo, V., & Paulraj, A. (2016). Sustainability in multi-tier supply chains: Understanding the double agency role of the first-tier supplier. Journal of Operations Management, 41(1), 42–60.

Williams, R. (2006). Generalized ordered logit/partial proportional odds models for ordinal dependent variables. The Stata Journal: Promoting Communications on Statistics and Stata, 6(1), 58–82.

Williams, R. (2016). Understanding and interpreting generalized ordered logit models. The Journal of Mathematical Sociology, 40(1), 7–20.

World Economic Forum. (2014). The Global Competitiveness Report 2014–2015. Full Data Edition. In K. Schwab (Ed.), Retrieved https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GlobalCompetitivenessReport_2014-15.pdf.

Wu, Z., & Pagell, M. (2011). Balancing priorities: Decision-making in sustainable supply chain management. Journal of Operations Management, 29(6), 577–590.