Abstract

In recent years, interest in family-to-work interference and its consequences has increased dramatically. Drawing on conservation of resources theory, we propose and test a dual spillover spiraling model which examines the indirect effects of family incivility on workplace interpersonal deviance through increasing family-to-work conflict (resource loss spiral) and decreasing family-to-work enrichment (resource gain spiral). We also examine the moderating effects of family-supportive supervisor behaviors on these indirect effects. The findings from a three-wave survey, with 455 employees and their coworkers in 60 teams, reveal that experienced family incivility (Time 1) induces more interpersonal deviance at work (Time 3) through facilitating family-to-work conflict (Time 2) and inhibiting family-to-work enrichment (Time 2). Such indirect deviation amplifying effects are mitigated by higher supervisor-level family-supportive supervisor behaviors (Time 1). Theoretical and practical implications are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Within the burgeoning field of research on family-to-work interference (eg., De Clercq et al., 2019; Peng et al., 2020; Venkatesh et al., 2019), family incivility (FI) and its detrimental effects on work outcomes have drawn growing attention (eg., Bai et al., 2016; De Clercq et al., 2018; Lim & Tai, 2014; Naeem et al., 2020). Defined as “low-intensity deviant behaviors with ambiguous intent that violate the norms of mutual respect in the family” (Lim & Tai, 2014, p. 351), FI appears in various forms, including ridiculing family members, excluding them from social interactions, as well as making demeaning remarks (Bai et al., 2016; De Clercq et al., 2018; Lim & Tai, 2014). Despite being a mild form of interpersonal mistreatment within families, FI is well documented as a factor undermining work outcomes, such as eroding work performance (Lim & Tai, 2014), diminishing organizational citizenship behavior (De Clercq et al., 2018), decreasing work engagement (Gopalan et al., 2021) and invoking counterproductive work behavior (Bai et al., 2016). Along these lines, Naeem et al. (2020) have demonstrated that FI is also linked to workplace incivility towards coworkers. We seek to extend their studies to find out whether FI can potentially escalate into increasingly deviant behaviors towards coworkers (i.e., workplace interpersonal deviance) beyond the confines of incivility.

Although previous studies have examined the underlying mechanisms linking FI to deleterious outcomes, their focus is predominantly limited to personal psychological and affective factors, such as psychological distress (Lim & Tai, 2014), emotional exhaustion (De Clercq et al., 2018) and negative emotions (Naeem et al., 2020). We aim to contribute to the literature by adopting a resource perspective (ten Brummelhuis & Bakker, 2012). From the resource perspective, there exist two vast but surprisingly disjointed research streams that focus on either work-family conflict or work-family enrichment (Chen & Powell, 2012). Previous studies have examined enrichment and conflict as distinct processes, each with its own antecedents (e.g., Frone, 2003; Greenhaus & Powell, 2006). Ten Brummelhuis and Bakker (2012) have argued, however, that the combination of both depleting and enriching processes may add to an integrative understanding of the work-family interface. Accordingly, they propose the work-home resources (W-HR) model, which suggests that conflict is attributed to demands and enrichment related to resources, respectively (ten Brummelhuis & Bakker, 2012). Drawing on conservation of resources (COR) theory (Hobfoll, 1998, 2001), we seek to understand how FI as a specific form of family demand both induces a loss spiral and disables a gain spiral. When inducing a loss spiral, FI drains resources in the existing resource pool and increases family-to-work conflict (FWC). In disabling a gain spiral, FI inhibits the creation of new resources and decreases family-to-work enrichment (FWE). To the best of our knowledge, there have been no studies yet that examine how family demands relate to both conflict and enrichment processes. Demands originating from the family domain deserve attention due to their tendency to compromise work outcomes (De Clercq et al., 2018).

In addition, we introduce family-supportive supervisor behaviors (FSSBs) as a macro resource operating at the supervisor level buffering against the negative outcomes associated with FI. As suggested by the work-home (W-HR) resources model (ten Brummelhuis & Bakker, 2012), macro resources represent the tools located within the social system in which a person is embedded. Conceptualized as a supervisor-level construct, FSSBs capture the shared team perceptions of what constitutes supervisor supportive behaviors regarding family responsibilities (Hammer et al., 2009) that emerge from “being exposed to common features, events and processes” (Klein & Kozlowski, 2000). Through social interactions, team members eventually develop consensus and agreement that their supervisor acts in consistent support of their management of family demands. Therefore, supervisor-level FSSBs are a sTable team characteristic rather than a volatile social support resource perceived idiosyncratically by individual employees (ten Brummelhuis & Bakker, 2012). Although Hammer et al. (2007) have suggested taking a multilevel approach to enhance the understanding of FSSBs, previous studies have primarily theorized them as individual-level perceptions (Cheng et al., 2021; Goh et al., 2015; Shockley & Allen, 2013; Zhang & Tu, 2018). We thus extend the W-HR model by specifying FSSBs as a supervisor-level macro-resource and explaining how it attenuates the potential, detrimental effects of a family demand. This is an important advancement since it answers the call to examine how features of an organizational context may inhibit incivility (Andersson & Pearson, 1999) and suggests how supervisor-level FSSBs can help employees address demands outside work by establishing a sTable support system (Lim & Tai, 2014).

Adopting a resource perspective to explain the spillover spiraling effects of FI on workplace interpersonal deviance, the current study makes important theoretical contributions to ethics literature and more specifically to the literature on deviant behaviors and incivility. Although research on workplace deviance has recently gained momentum, most scholars have limited their inquiries to organizational and personal factors as predictors of deviance (Bennett et al., 2018). Little is known about how workplace deviance is linked to a specific family demand. Our study provides important empirical evidence of FI as an antecedent of workplace interpersonal deviance. We reveal how even a mild but chronic family demand can spill over and escalate into interpersonal deviant behaviors in the workplace, thus providing a unique perspective in understanding how workplace interpersonal deviance evolves outside of the context of a workplace. Second, we contribute to the incivility literature by suggesting that incivility has the potential to beget increasingly intense interpersonal mistreatment at work, thus moving beyond the established finding of experienced incivility leading to instigated incivility (Naeem et al., 2020; Rosen et al., 2016) and providing evidence of an incivility spiraling effect (Andersson & Pearson, 1999). Evidence that various forms of mistreatment within the family and the work domains are related, as part of a mesosystem (ten Brummelhuis & Bakker, 2012), sheds a new light on the potential adverse outcomes of FI. In addition, we provide insights into the mechanisms underlying the relationship between FI and workplace interpersonal deviance from the resource perspective. By examining FWC and FWE processes integrally, we reveal how the presence of a resource loss spiral and the absence of a resource gain spiral serve as the linchpins between FI and interpersonal deviance. Examining the mechanisms through the lens of both a resource loss spiral and a gain spiral offers unique insights to the question of why victims of FI might turn into instigators of interpersonal deviance at work. Lastly, we enrich the understanding of the boundary conditions of FI by identifying FSSBs as a supervisor-level macro resource that attenuates the adverse effects of FI. Despite the abundance of incivility research, relatively less is known about what organizations can do in terms of support to reduce the detrimental effects of FI specifically. Our conceptualization of FSSBs as a supervisor-level construct provides individuals with a sTable resource to draw upon in the face of FI, rather than the less organized, informal personal support from a supervisor.

Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

COR Theory

In his seminal work on conservation of resources, Hobfoll (1989) defined resources as objects, personal characteristics, conditions, or energies that facilitate goal attainment. Stress occurs as a response to a net loss of resources, or the threat of a loss of resources (Hobfoll, 1989). Because resource loss can be so stressful, people must invest more resources to offset further resource loss. Once initial loss occurs, people become increasingly vulnerable to the ongoing diminishment of resources (Hobfoll, 2001). Described as a process by which initial loss begets further loss, a loss spiral develops when those with fewer resources are vulnerable to resource loss and lack the resources to offset the losses incurred (Hobfoll, 1989, 2002; ten Brummelhuis & Bakker, 2012). By contrast, a gain spiral is described as a process by which greater resources lead to even more attainment of resources. Those who possess resources are more capable of resource gain (Hobfoll, 2001). The creation of new resources from existing ones constitutes an ongoing cycle (ten Brummelhuis & Bakker, 2012). Empirically, studies have supported a loss cycle induced by burn-out through accumulating job demands and draining job resources (ten Brummelhuis et al., 2011). Numerous studies have also provided evidence for the gain spirals between job resources and work engagement (e.g., Hakanen et al., 2011; Xanthopoulou et al., 2009). Empirical evidence has also been found in support of the integration of both loss and gain spirals (Braun & Nieberle, 2017; Chen & Powell, 2012; Wayne et al., 2013, 2020; Wu et al., 2020).

The Effects of FI on FWC and FWE

FI constitutes a subtle but chronic form of emotional and cognitive demand that requires sustained mental and emotional efforts to cope (Bai et al., 2016; De Clercq et al., 2018; Lim & Tai, 2014). As a family contextual demand, FI either threatens the loss or entails the actual loss of affective resources, such as intimacy and affection from family members, positive feelings about oneself (Hobfoll, 1989) and cognitive resources such as social identity (Andersson & Pearson, 1999) and attentional resources (Pan et al., 2021; Porath & Erez, 2007). To protect against this potential loss, or recover from an actual loss, additional resources need to be expended; these include time, energy, emotions and attention. Prolonged exposure to the chronic demand of FI requires continuous investment of these resources and depletes any that are potentially available from within the family domain. As such, one has to extract resources from the work domain, which leaves insufficient resources to function optimally (De Clercq et al., 2018; ten Brummelhuis & Bakker, 2012). These, for example, include intrusive thoughts about incivility incidents (Lim & Lee, 2011) or using time at work to Figure out coping strategies. It may become difficult to attend to work tasks while managing these intrusive thoughts and worries. Deterioration in the work domain also involves the actual or potential loss of valuable resources, such as feelings of competence and assuredness, status at work, trust from management, employment and financial stability. And, as previously mentioned, resource loss is inherently stressful, sending individuals into a cascade of detrimental resource expenditure to offset further loss (Hobfoll, 2001). The ongoing resource loss and investment drains employees’ resource pool and further impedes the ability to focus on work goals. FWC captures the loss spiral whereby the family demand of FI induces initial resource loss, leaving the victims more susceptible to ongoing loss and resulting in further deterioration of relationships and productivity in the work domain (Hobfoll, 2001). Conflict within the family has been proven to be related to high levels of work–family conflict (Byron, 2005). Thus, we propose:

Hypothesis 1

Family incivility is positively related to family-to-work conflict.

COR theory assumes resources can generate new resources (Hobfoll, 2002). A gain spiral develops when those who have more resources invest these resources to enrich their resource pool (Hobfoll, 1989, 2001). FWE can be understood as a gain spiral whereby resources from the family domain facilitate further accumulation of resources, resulting in an enhancement of performance in the work domain.

In the face of the resource-draining situation caused by FI, its victims are less likely to generate resources, and have fewer resources to be transferred to the work domain or to promote the positive affect that facilitates performance in the work domain (Greenhaus & Powell, 2006). Specifically, uncivil behaviors that violate the norm of mutual respect create a distressful family environment, diminishing the likelihood of developing positive emotions (Greenhaus & Powell, 2006) and valuable social-capital resources, such as positive family ties and psychological resources like favorable self-evaluation (Lim & Tai, 2014). Without both the generation and the transfer of such valued resources, enhanced work performance is less likely. In other words, FI makes the gain spiral unlikely by inhibiting resource development and transfer from the family to the work domain, and consequently, the facilitation of effective work performance. Gopalan et al. (2021) have argued that FI can lead to lower FWE in the new normal of extended working from home due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, we propose:

Hypothesis 2

Family incivility is negatively related to family-to-work enrichment.

The Indirect Effects of FI on Workplace Interpersonal Deviance via FWC and FWE

Anderson and Pearson (1999) have conceptually distinguished incivility from deviant behaviors. The definition of employee deviance as “voluntary behavior that violates significant organizational norms and, in so doing, threatens the well-being of an organization, its members, or both” (Robinson & Bennett, 1995, p. 556) implies that employee deviance is inclusive of, but not limited to, incivility. Deviant behaviors can take the form of moderate- to high-intensity violence or aggression with obvious intent to harm, as well as lesser forms of incivility with ambiguous intent to harm (Andersson & Pearson, 1999). In our current study, we have chosen to focus on workplace interpersonal deviance, which is directed at people rather than organizations. A deviation-amplifying spiral refers to the process when an exchange of incivilities escalates into an exchange of increasingly counterproductive behaviors (Andersson & Pearson, 1999).

The W-HR model suggests that contextual demands from one side of the work–home interface will deplete personal resources and undermine performance on the other side of the work–home interface (ten Brummelhuis & Bakker, 2012). Following this logic, we argue that coping with the chronic family demand of FI causes FWC by draining personal resource reservoirs in both the family and the work domains and inhibiting employee functioning in the work domain. FWC reflects a loss spiral whereby the initial negation of personal resources induces further loss (Hobfoll, 2002). Being subjected to a stressful situation involving a loss spiral over a prolonged period, the victims of FI experience FWC, which leads to subsequent losses of valuable resources, such as attention to work (Pan et al., 2021; Rosen et al., 2016), trust from management, employment stability and social identity while inducing negative affect like frustration and anger. The distressful resource loss and negative affect jointly cause individuals to ignore or defy norms and therefore be less capable of regulating behaviors and inhibiting tendencies toward deviations. Consequently, they engage in increasingly counterproductive behaviors. Rosen et al. (2016) have argued that diminished attentional resources lead to self-regulatory failures resulting in the inability to suppress acts that deviate from the norm of mutual respect. In addition, studies have suggested that deviance can be performed as emotion-focused coping to reduce negative emotional responses to stressful events, thus conserving resources and preventing further resource loss (Ferguson et al., 2012; Krischer et al., 2010). For example, treating coworkers in an aggressive or hostile manner allows an individual to increase his or her sense of control over the stressful situation (Krischer et al., 2010).

Taken together, the lesser form of mistreatment spills over from the family to the work domain by triggering a loss spiral as represented by FWC, which further results in a dearth of sufficient resources to regulate behaviors conforming to interpersonal norms (Rosen et al., 2016). Thus, FI escalates into a more amplified form of interpersonal deviance that threatens the well-being of others at work (Robinson & Bennett, 1995) via increased FWC. Bai et al. (2016) have demonstrated that FI induces counterproductive work behaviors by depleting the personal resource of state self-esteem. Chen et al. (2020) have confirmed family undermining related to workplace deviance through psychological strain. Hence, we propose:

Hypothesis 3

Family-to-work conflict mediates the relationship between family incivility and workplace interpersonal deviance.

Based on the work-family enrichment model proposed by Greenhaus and Powell (2006), enrichment involves two primary components, namely, generating resources in Role A and enhancing performance in Role B through the transfer of resources from Role A to Role B directly or through the link of positive affect. In COR theory, Hobfoll (2001) proposed that resource gain spirals occur when those who obtain resources are more capable of resource gains. Since the experience of FI makes the creation of valuable resources like the cultivation of strong, secure family ties and favorable self-evaluation and positive emotions unlikely, gaining further resources and investing them for improved functioning in the work domain are in turn less likely as well. In other words, FI reduces the likelihood of FWE. As FI continues to drain resources, new resources are needed to offset the ongoing resource loss (Hobfoll, 2001). However, few new resources are created in the family domain and added to the work domain due to decreased FWE. Therefore, employees have insufficient resources to exercise self-regulation and act in accordance with workplace interpersonal norms (Rosen et al., 2016). Instances of workplace interpersonal deviance can be thought of as self-regulatory failures (Andersson & Pearson, 1999). Taken together, as FI depletes resources and renders FWE less likely, employees must expend resources, and yet they are not replenished by new resources due to lower FWE. They have insufficient resources to exercise self-regulation and suppress acts that deviate from workplace norms for mutual respect. As a consequence, they may engage in more intensified forms of harm on others (Andersson & Pearson, 1999; Rosen et al., 2016). Recent evidence from Gopalan et al. (2021) has suggested the negative effect of FI on work engagement through FWE. Based on these arguments, we argue that FI is associated with reduced FWE, which further induces workplace interpersonal deviance. Therefore, we propose:

Hypothesis 4

Family-to-work enrichment mediates the relationship between family incivility and workplace interpersonal deviance.

The Moderating Effects of FSSBs on the Indirect Relationships

Greenhaus and Powell (2006) have defined a resource as “an asset that may be drawn on when needed to solve a problem or cope with a challenging situation” (p. 80). As a chronic family demand, FI depletes valued resources such as self-esteem, positive family ties, and emotions. As previously mentioned, this depletion process requires a continuous investment of resources to recover from and protect against loss (Hobfoll, 2001).

FSSBs, referred to as discretionary behaviors exhibited by supervisors supportive of employees’ family responsibilities, take the form of emotional and instrumental support, role-modeling and creative work-family management (Hammer et al., 2009). FSSBs are found to be a more psychologically and functionally useful resource to cope with work-family demands than any other type of general support (Kossek et al., 2011). Supervisors with high FSSBs are more sensitive to employees’ family responsibilities. They act as sympathetic listeners to employees’ family-related concerns, offer day-to-day assistance for the management of family demands, demonstrate how they solve family issues by role-modeling, or proactively initiate efforts to facilitate effective functioning on and off work (Hammer et al., 2009).

When first conceptualized, the construct of FSSBs was presented as a supervisor-level construct (Hammer et al., 2007). Pan et al. (2021) have provided preliminary evidence for the conceptualization of FSSBs at the supervisor level. They argue that “employees managed by the same supervisor are likely to have a shared experience of FSSBs” (Pan et al., 2021, p. 6). In the same vein, we conceptualize FSSBs as team members’ shared perceptions of their supervisor being supportive of their well-being in both the work and the family domains. This perceptual consensus emerges from common exposure to clear and consistent messages from the supervisor about what is valued. In a team where the supervisor consistently implements family-friendly policies, embraces a family-supportive culture, overtly acts as a role model of effective work-family management and clearly communicates care and concerns for employees’ overall wellbeing, there is high supervisor-level FSSBs agreement. The high agreement indicates a strong situation where all members believe their supervisor values balance between work and family responsibilities, and supports their efforts to manage family demands (Marescaux et al., 2020). As such, the shared perceptions of FSSBs represent a sTable macro resource, which refers to the consistent characteristic of the team in which individual employees are embedded (ten Brummelhuis & Bakker, 2012), rather than a volatile contextual resource of social support supplied by the supervisor as suggested by individual perceptions of FSSBs.

COR theory posits that resources can buffer against stress and that people with more resources are less negatively affected when they face resource drains (Hobfoll, 2002). Over time, the sTable macro resource of supervisor-level FSSBs protects employees from resource loss in the face of the chronic family demand of FI (ten Brummelhuis & Bakker, 2012). When employees learn and share that they can rely on the emotional and instrumental support from a supervisor, they are psychologically more resilient and functionally more prepared to manage any distress (Goh et al., 2015) induced by the family demand of FI. They are less vulnerable to resource loss, which allows for less interference with work performance. Due to decreased resource loss, they are less likely to deviate from the workplace interpersonal norms. Hence, we assume supervisor-level FSSBs alleviate the resource loss process that links the family demand of FI and interpersonal deviance at work through FWC. In contrast, lower supervisor-level FSSBs create a weak situation, where employees receive low support from their supervisor regarding fulfilling their family responsibilities. In such a case, employees are more vulnerable to ongoing resource loss since they cannot count on their supervisor to address the resource draining situation induced by FI. Consequently, they may not have sufficient resources to regulate behaviors and act in accordance with workplace interpersonal norms. Thus, the resource loss process that accounts for the relationship between FI and workplace interpersonal deviant behaviors is heightened.

Previous research has supported the cross-level moderating effect of supervisor work-family support on the relationship between daily workload and daily work-family conflict (Goh et al., 2015). Recent findings that team-level authentic leadership functions as a macro resource above and beyond individual-level perceptions of authentic leadership to buffer followers’ WFC (Braun & Nieberle, 2017) also provide indirect evidence. In line with these arguments as well as previous research, we propose that the relationship between FI and workplace interpersonal deviance via FWC is attenuated for individuals who receive higher supervisor-level FSSBs. Thus, we propose:

Hypotheses 5

The indirect relationship between family incivility and workplace interpersonal deviance through family-to-work conflict is moderated by supervisor-level FSSBs, such that the indirect relationship is weaker when supervisor-level FSSBs are high.

In line with COR theory’s notion that resources can generate new resources (Hobfoll, 2002), higher supervisor-level FSSBs function as a macro resource to facilitate the generation of more resources by employees when confronted by the family demand of FI. Specifically, they may feel more secure and comforTable reaching out to a supervisor, rather than keep their concerns to themselves. Through talking and listening, they may develop new perspectives about managing the situation (Greenhaus & Powell, 2006), such as figuring out the underlying reasons for the family problem and taking the initiative to manage frustration and emotional burdens (Rosen et al., 2016). Thus, a sense of personal control over the situation is enhanced. They may also acquire specific coping skills from the role-modeling of a supervisor to improve the situation at hand. Emotional and instrumental support from a supervisor may boost employees’ self-evaluation (Bandura, 1977), such as enhanced self-efficacy and self-esteem (Greenhaus & Powell, 2006). They may even build enough confidence to enhance their skills in coping with the family demand. As a result of resource replenishment from high supervisor-level FSSBs, the resource gain process is less likely to be disabled by the family demand of FI. Consequently, employees have more resources to regulate their behaviors in observance of workplace interpersonal norms. Hence, the disabled resource gain process that links the family demand of FI and interpersonal deviance at work will be mitigated. In contrast, when there is a shortage of supervisor-level FSSBs, employees’ resources will remain unreplenished. The resource gain spiral is unlikely to be triggered, strengthening the disabled resource gain process that underlies the relationship between FI and employee interpersonal deviant behaviors. Previous studies demonstrate the moderating effect of FSSBs on the indirect link from ethical leadership to employee family and life satisfaction via work-to-family enrichment (Zhang & Tu, 2018).

Taken together, the relationship between FI and workplace interpersonal deviance via FWE is attenuated for individuals who perceive more supervisor-level FSSBs. Therefore, we propose:

Hypotheses 6

The indirect relationship between family incivility and workplace interpersonal deviance through family-to-work enrichment is moderated by supervisor-level FSSBs, such that this indirect relationship is weaker when supervisor-level FSSBs are high.

Methods

Research Design and Data Collection

The sample in this study was from the alumni network of a business school in the southeast of China. We obtained the alumni list from the alumni office of this school, and randomly contacted 150 alumni, who further invited 10–15 of their team members to participate in our survey. We informed the participants of the intentionality of the survey and assured confidentiality of their responses. Finally, 593 employees in 66 organizations agreed to participate. We obtained the contact information of these employees and collected their responses ourselves to avoid any leakage of information and to maintain confidentiality.

We applied a multiphase (three-wave) survey data collection procedure: at Time 1, we distributed a first-round questionnaire to all 593 employees and asked them to rate their experiences of FI and FSSBs. We also mailed each employee a gift card (value of 10 dollars) to increase response rate. Of these, 535 returned their first-round questionnaires. Two months later (Time 2), we collected the two mediators (FWC and FWE) from the 535 employees. This time, 486 returned their questionnaires. Two months later (Time 3), the dependent variable, workplace interpersonal deviance, was rated. We asked each of the 486 employees to rate three of their team members who attended the previous two rounds of data collection and averaged the multiple ratings to get the evaluation of individual participant’s interpersonal deviances. The ratees’ names were identified in the third-round questionnaire to each rater, and we made sure all employees would be rated during this round. Obtaining employee behavior data from multiple coworkers is a common practice in management survey research and is preferred when addressing evaluations about undesirable behaviors (e.g., Den Hartog & Belschak, 2012; Lee & Allen, 2002; Peng et al., 2020). Doing so has several advantages compared to supervisor-rated data, and these are: (1) coworkers who are victims have more accurate information about focal employee’s interpersonal deviances than supervisors; (2) multiple coworkers can provide multi-source data, which is better than single-source data from supervisors; (3) when team size is large enough, supervisors may be overworked from the demands of rating a large number of employees, while coworkers might rate only a small number of employees and provide higher-quality data. The indices of aggregation also justified the consistency of the multiple peer-rated deviance scores (Rwgmean = 0.95, ICC1 = 0.24, ICC2 = 0.42) (Bliese, 2000; James et al., 1993). In this round, six teams had less than two participants, thus we deleted them from the final dataset. Finally, after deleting non-matched and incomplete data, we obtained a dataset of 455 individuals in 60 teams for further analyses (average team size = 7.58; overall response rate = 76.7%). With the three-wave multi-source data collection procedure, we could minimize the problem of common method variance in our dataset (Podasakoff et al., 2003).

The current sample represented a variety of industries including 20 organizations from manufacturing (33.3%), 15 from the service sector (25.0%), 14 from finance and insurance (23.3%), 4 from transportation (6.7%), and others (11.7%). Among the sample, 50.8% were under 29 years old, 32.5% were between 30–39 years old, 14.9% and 1.8% were between 40–49 and 50–59 years old, respectively. Of these, 58.9% were male.

Measurement

The measurement was translated from English into Chinese. We used a back-translation process (Brislin, 1986) by which two bilingual experts independently translated the English measurement items into Chinese and back-translated them. The two experts exchanged their translations and discussed the differences until convergence was achieved.

Family incivility. Lim and Tai’s (2014) 6-item scale was used to measure the extent to which employees evaluate their perceptions of FI. A sample item is: “in the past year, have you been in a situation where any of your family members put you down or was condescending to you?” Answers were given on a 5-point scale ranging from “not at all” (as 1) to “many times” (as 5), and the Cronbach’s alpha was 0.91.

Family-to-work conflict. Carlson and Karmar’s (2000) 9-item FWC scale was used to measure the construct. The sample items are: “due to stress at home, I am often preoccupied with family matters at work” and “the time I spend with my family often causes me not to spend time in activities at work that could be helpful to my career.” Answers were given on 5-point scales ranging from “strongly disagree” (as 1) to “strongly agree” (as 5). The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.87.

Family-to-work enrichment. The three-dimension FWE scale (Carlson et al., 2006) was used to measure this construct. Sample items are: “my involvement in my family helps me to gain knowledge and this helps me be a better worker” and “my involvement in my family makes me feel happy and this helps me be a better worker.” Answers were given on a 5-point scale ranging from “strongly disagree” (as 1) to “strongly agree” (as 5). The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.91.

Family-supportive supervisor behaviors. The 14-item FSSBs scale from Hammer et al. (2009) was used to measure the family supportive behaviors of supervisors. Sample items are: “my supervisor is willing to listen to my problems in juggling work and non-work life” and “I can rely on my supervisor to make sure my work responsibilities are handled when I have unanticipated non-work demands.” Answers were given on a 5-point scale ranging from “strongly disagree” (as 1) to “strongly agree” (as 5). The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.96.

Workplace interpersonal deviance. To measure workplace interpersonal deviance we used a 7-item scale from Bennett and Robinson (2000). Sample items are: “this colleague acted rudely toward someone at work” and “this colleague said something hurtful to someone at work.” Answers were given on a 5-point scale ranging from “strongly disagree” (as 1) to “strongly agree” (as 5). The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.91.

Control variables. Following similar research, employee age, gender, tenure, and weekly work hours were included as controls (Allen & Finkelstein, 2014; Netemeyer et al., 1996). Age was coded with “29 years old” as 1, “30–39” as 2, “40–49” as 3, “50 and above” as 4. Gender was coded with 1 for female and 0 for male. Tenure was coded with “1–5 years” as 1, “6–10 years” as 2, “11–15 years” as 3, “16–20 years” as 4, and “above 20 years” as 5. Weekly working hours were coded with “below 40 h a week” as 1, “40–50 h a week” as 2, and “above 50 h a week” as 3. We also controlled the type and years of establishment of organizations. The type of organization was coded with “state-owned organization” as 1 and “non-state-owned organization” as 0.

Data Analytic Strategy

Since our data were hierarchical in nature with 455 individuals nested in 60 teams, using a multilevel technique was more appropriate. We applied hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002) to analyze our data. HLM controls for the non-independences in the data by partitioning the total variance into within-group and between-group components. It could not only estimate the level-1 mediations, but also test the cross-level moderation on the level-1 mediations.

In our model, FI, FWC, FWE, and workplace interpersonal deviance were at the individual level (i.e., level-1 variables) and FSSBs should be regarded as a higher-level variable. The aggregation indices of FSSBs supported aggregating the individual ratings of FSSBs to the supervisor level (Rwg = 0.92, ICC1 = 0.27, ICC2 = 0.74) (Bliese, 2000; James et al., 1993).

For mediation checks of H3 and H4, we adopted the bias-corrected bootstrapping mediation test approach suggested by Preacher and Hayes (2004). To test the moderated mediation of H5 and H6, we followed Edwards and Lambert’s (2007) moderated path analysis approach, which considers moderation and mediation simultaneously, rather than separately. In this paper, we are interested in examining the role of FSSBs as a supervisor-level macro resource to buffer against the negative outcomes associated with FI. Besides, previous studies have indicated that FSSBs significantly predicted FWC and FWE (Crain & Stevens, 2018; Hammer et al., 2009, 2013). Therefore, it is more appropriate to test FSSBs at the first stage of the moderated mediation mode (Edwards & Lambert, 2007). The results of multilevel CFA, correlation analysis, and hypotheses testing were illustrated below.

Results

Analyses of Multilevel Measurement Model

Table 1 presented the results of the multilevel CFA with all five variables. The fit statistics indicated that the baseline model with the five factors (FSSBs at the supervisor level and FI, FWC, FWE, and interpersonal deviance at individual level) had a good model fit (χ2 = 583.46, df = 440; RMSEA = 0.027; CFI = 0.99; SRMR = 0.03) and all items had significant loadings on their respective factors. We also tested several competing CFA models for discriminant validity. The results were shown in Table 1 and demonstrated that none of the competing models had a better model fit than the five-factor baseline model, indicating that the five factors were distinct constructs. Furthermore, the average variance extracted (AVE) of each factor was computed, and the estimates of FI, FSSBs, FWC, FWE, and interpersonal deviance were 0.77, 0.95, 0.74, 0.70, and 0.83, respectively. All of these estimates were greater than the benchmark of 0.50 and larger than the squares of the correlations among these constructs, providing further evidence of discriminant validity (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). A summary of the descriptive statistics and correlations among all variables was presented in Table 2. The correlations between FI, FWC, FWE, and interpersonal deviance were found to be in the expected directions.

Hypotheses Testing

Before hypotheses testing, we needed to check if the dependent variables (i.e., FWC, FWE and interpersonal deviance) have significant between-group variance (Seibert et al., 2004). HLM null model tests showed that the ICCs of FWC, FWE and interpersonal deviance were 0.20, 0.09, and 0.23, respectively, indicating sufficient between-group variance to apply cross-level HLM analyses.

Hypothesis 1 proposed that FI would be positively related to FWC. Model 2 in Table 3 showed that the coefficient of FI on FWC was significant (β = 0.17, p < 0.01). Thus, H1 was supported. Hypothesis 2 proposed that FI would be negatively related to FWE. Model 4 in Table 3 showed that f FI had a significant and negative relationship with FWE (β = − 0.14, p < 0.01). Thus, H2 was also supported.

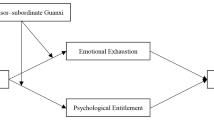

Hypotheses 3 and 4 proposed the mediating effects of FWC and FWE between FI and workplace interpersonal deviance, respectively (Figs. 1, 2). When we introduced FI, FWC, and FWE into the regression of interpersonal deviance (M6), only FWC and FWE were significantly related to interpersonal deviance (M6: βs = 0.06 and − 0.07, respectively, both ps < 0.05). To test the mediation relationship, we applied the Monte Carlo Bootstrapping method (Preacher & Selig, 2012) and bootstrapped 20,000 estimations of the indirect effect of FI and workplace interpersonal deviance through mediators. The indirect effect via FWC was 0.01 and its 95% confidence interval was [0.001, 0.022], not including zero; the indirect effect via FWE was 0.01 and its 95% confidence interval was [0.001, 0.021], not including zero, too. Thus, these results provide supportive evidence of Hypotheses 3 and 4.

Hypotheses 5 and 6 proposed that supervisor-level FSSBs moderated the indirect effects of FI on interpersonal deviance via FWC and FWE, respectively. We first adopted the traditional moderation test recommended by Aiken and West (1991). We introduced the main effects of FI and FSSBs as well as their cross-level interaction term (FI × FSSBs) into the regression of FWC in M8. The results in M8 showed that the interaction term was significantly related to FWC (M8: γ = − 0.11, p < 0.05). Thus, FSSBs had a negative moderating effect on the relationship of FI and FWC. To understand this interaction, we plotted FI and FSSBs at values one standard deviation above and below their means (Aiken & West, 1991). The plot of the interaction is shown in Fig. 3. The simple slopes of the regression lines shown in the Figure were then examined. When FSSBs were low (under one standard deviation), there was a significant and positive relationship between FI and FWC (simple slope = 0.28; t = 4.19, p < 0.01) whereas when the FSSBs were high, FI was not significantly related to FWC (simple slope = 0.05; t = 0.77, p > 0.10). We adopted the bootstrapping approach (bootstrap = 20,000) to examine the first-stage moderation of FSSBs on the indirect link between FI and interpersonal deviance via FWC (Edwards & Lambert, 2007). The results showed that the indirect effect varied significantly as a function of FSSBs. Specifically, the indirect effect through FWC was significant (indirect effect = 0.03, 95% CI [0.01, 0.05], not including zero) when FSSBs were low, whereas the indirect effect was not significant (indirect effect = 0.01, 95% CI [− 0.01, 0.02], including zero) when FSSBs were high. The difference between these two conditions was also significant (difference = 0.02, 90% CI [0.002, 0.04]). Thus, H5 was supported.

Adopting the same testing procedure for H6, we introduced the main effects of FI and FSSBs as well as their cross–level interaction in the regression of FWE in M10. The interaction term was significantly and positively related to FWE (M10: γ = 0.09, p < 0.05), indicating a positive moderation of FSSBs on the relationship between FI and FWE. The interaction was also plotted in Fig. 4. The simple slope analysis showed that when FSSBs were low (under one standard deviation), there was a significant and negative relationship between FI and FWE (simple slope = − 0.23; t = 3.80, p < 0.01) whereas when FSSBs were high, FI was not significantly related to FWE (simple slope = − 0.04; t = 0.60, p > 0.10). The bootstrapping results showed that the indirect effect through FWE also varied significantly as a function of FSSBs. Specifically, the indirect effect was significant (indirect effect = 0.03, 95% CI [0.01, 0.05], not including zero) when FSSBs were low, whereas the indirect effect was not significant (indirect effect = 0.00, 95% CI [− 0.01, 0.01], including zero) when FSSBs were high, and the difference was also significant (difference = 0.03, 95% CI [0.01, 0.06]), which supported H6.

General Discussion

Drawing on COR theory, we investigate whether FI can spill over and amplify into more intense forms of interpersonal deviance at work through a resource loss spiral and a disabled resource gain spiral. We also explore the conditions under which any indirect effects can be attenuated. With the data collected from a multiphase three-wave survey study, we support the idea that the experiences of FI spiral toward interpersonal deviance at work through increased FWC and decreased FWE. In addition, we also find that these indirect relationships are weakened by high supervisor-level FSSBs.

The findings on the indirect relationship between FI and workplace interpersonal deviance are significant. In general, they are consistent with previous results, which demonstrate that the detrimental effects of FI spill over to workplace, undermining functioning in the work domain (Bai et al., 2016; De Clercq et al., 2018; Gopalan et al., 2021; Lim & Tai, 2014). By focusing on workplace interpersonal deviance as the outcome variable, we shed a unique light on how the interpersonal mistreatment in both the family and the work domains are related. The findings demonstrate that incivility may escalate into moderate- to high-intensity deviant behaviors with the more obvious intent to harm third parties in the workplace and reveal that interpersonal mistreatment at work may potentially originate from a family demand external to the workplace.

Drawing on COR theory, we conceptually integrate depleting and enriching processes in our proposed model and empirically support that FI as a contextual family demand causes interpersonal mistreatment at work through a resource loss process and a disabled resource gain process. Our findings of these dual mediating processes are consistent with the arguments of Chen and Powell (2012), which state that resource gain and loss represent independent and separate processes, rather than at opposite ends of the same continuum. Previous studies which have examined the dual mediating processes of conflict and enrichment mostly focus on job demands/resources as the antecedents of work-to-family direction of conflict and enrichment. For example, Wayne et al. (2013) have shown that work-to-family enrichment and conflict mediate the relationship between family-supportive organizational perceptions and employee affective commitment. Wu et al. (2020) have found that surface acting as a job demand undermines service performance via work-to-family conflict, and that deep acting as a job resource enhances service performance via work-to-family enrichment. Compared with personal and family resources, Wayne et al. (2020) have found work resources are stronger predictors of work-to-family conflict and enrichment, which further explains work–family balance satisfaction. We have contributed above and beyond their work by focusing on a family demand as the predictor, and negative work interpersonal behaviors as the outcome of the family-to-work direction of conflict and enrichment. While the resource depleting mechanism of FI as found in our study is consistent with previous studies (e.g., Bai et al., 2016; De Clercq et al., 2018; Lim & Tai, 2014), the link between FI and the disabled resource enriching process sheds light on the notion that FWE can be related to contextual demands rather than exclusively tied to contextual resources, as suggested by ten Brummelhuis and Bakker (2012).

Although investigations into the moderating effects of FSSBs have been scarce (Crain & Stevens, 2018), our result is generally consistent with previous findings that FSSBs serve as a buffer against the adverse effects of work–family relationships (Goh et al., 2015; O'Driscoll et al., 2003; Shockley & Allen, 2013; Zhang & Tu, 2018). Previous studies have mainly examined the moderating effects of FSSBs on the relationships between work–family conflict/enrichment and individual health outcomes including psychological strain and blood pressure (O'Driscoll et al., 2003; Shockley & Allen, 2013) as well as on the relationships between work domain factors, such as daily workload, ethical leadership and work–family conflict/enrichment (Goh et al., 2015; Zhang & Tu, 2018). Our study addresses the buffering effects of FSSBs on the indirect relationship between mistreatment in the family and the work domains, which, to our knowledge has not been examined previously. Our analysis suggests that when FSSBs were high, FI was not significantly related to either FWC or FWE and that the indirect effect between FI and interpersonal deviance via FWC or FWE was not significant. This pattern of results suggests the shared perceptions of FSSBs as a macro resource successfully protect employees from resource loss and disabled resource gain processes.

Theoretical Implications

FI deserves more attention given its tendency to comprise work outcomes. We extend previous research which aims to reveal the relationship between FI and job performance (Lim & Tai, 2014), counterproductive work behavior (Bai et al., 2016), organizational citizenship behavior (De Clercq et al., 2018) and work engagement (Gopalan et al., 2021). We do so by focusing on interpersonal deviant behaviors at work as the outcome and testing the effects of cross-domain deviation amplifying. Our findings suggest that the experiences of FI may beget more serious interpersonal mistreatment at work beyond incivility through increased FWC and decreased FWE. In doing so, we not only empirically support but also expand the boundary of the conceptual framework for the spiraling effect of work incivility (Andersson & Pearson, 1999) as well as the notion of incivility begetting further instances of incivility (Naeem et al., 2020; Rosen et al., 2016).

While we follow previous findings that FWC and FWE are conceptually distinct constructs (e.g., Carlson et al., 2006), we advance the literature by integrating them as both mediating the path from FI to workplace interpersonal deviances, and also explaining the separate underlying mechanisms. The resource loss spiral explains how FI depletes resources in the current resource reservoirs, causing harmful interpersonal behaviors at work through heightened FWC. The resource gain spiral reveals how FI disables the capacity to generate additional resources, resulting in dysfunctional interpersonal behaviors due to diminished FWE. Thus, we contribute to an integrated knowledge of the depleting and enriching mechanisms underlying the relationship between FI and interpersonal deviance and add new empirical evidence of resource loss and gain spirals that originate from a family demand.

Our findings support the moderating effects of supervisor-level FSSBs on the indirect relationship between FI and interpersonal deviance at work via FWC and FWE, suggesting that the employees who receive higher supervisor-level FSSBs will experience fewer adverse effects from FI. Marescaux et al. (2020) have indicated that “FSSB agreement is an important construct in and of itself” (p. 12). The supervisor-level conceptualization accounts for how a shared reality (Marescaux et al., 2020) emerges out of team interactions and answers the call to explore how FSSBs operate within teams (Crain & Stevens, 2018). The findings also reveal how supervisor-level agreement about FSSBs functions as a macro-resource available within the team context to protect employees against resource loss and disabled resource gain processes in the face of the family demand. Our findings thus contribute to current knowledge about how features of the team context may help to alleviate the adverse effects of FI.

Practical Implications

The present study highlights important implications for practice. First, organizations cannot afford to ignore FI as a potential incursion into the workplace and its detrimental consequences. As our findings suggest, victims of FI can become instigators of overt forms of interpersonal deviance at work. Given the adverse spillover and deviation amplifying effects of FI to the workplace, it is important for managers to be mindful of the fact that deviance at work may originate from incivility experiences beyond work.

Second, organizations can learn to develop innovative ways to address the challenges brought into the workplace from FI. Our study indicates that FI undermines interpersonal interactions at work through a resource loss process and a disabled resource gain process, and that supervisor-level FSSBs can alleviate these indirect relationships. Therefore, it is critical for organizations to encourage supervisors to develop awareness about family support issues, to increase sensitivity to employees’ work–family needs (Zhang & Tu, 2018) and to exhibit family supportive behaviors. For example, supervisors may listen to employees’ family-related concerns, share advice or personal experiences on how to deal with family demands such as FI, offer day-to-day assistance in facilitating employees’ emotional regulation and interpersonal interactions, and restructure work to accommodate employees’ family concerns. Employees would particularly benefit from FSSBs applied in a consistent manner, which convey with necessary certainty that their work and family balance will be valued and supported (Marescaux et al., 2020). Strengthening FSSBs also helps to shape family-supportive culture that allows employees to talk about their family concerns, such as FI experiences, making them feel safe, and seeks support from organizational peers. In addition, organizations can provide training programs that help employees to prevent and identify FI, regulate emotions, and address this issue in more constructive ways while maintaining confidentiality so that the issues of FI can be resolved without potential inhibition.

Strengths, Limitations and Directions for Future Studies

First, the three-wave research design reduces the likelihood of common method variance. However, the possibility of reverse causal relationships cannot be ruled out. Future studies may apply a rigorous longitudinal design to collect data pertaining to all variables at different times. Second, workplace interpersonal deviance is measured by multiple coworkers, answering the call for peer assessment to provide more accurate accounts of actual deviance within the team (Ferguson et al., 2012). Future studies may also consider further reducing common method bias by obtaining data of FSSBs from supervisors.

The research on FI can be advanced in several ways. First, researchers can explore whether FI links to other forms of interpersonal mistreatment at work, such as violence and aggression (Andersson & Pearson, 1999). Our finding suggests FI begets interpersonal deviance at work, which can be more intense and less ambiguous than workplace incivility in terms of the intent to harm. Future studies can test the spillover of deviation amplifying effects by examining other interpersonal mistreatment behaviors as outcome variables. Future studies can unravel the potential mediating mechanisms from cognitive perspectives. Cognitive mechanisms such as self-regulation can be examined. We encourage future research to explore additional moderators that reveal what organizations can do to reduce the detrimental effect of FI. The type and variety of resources organizations can provide their employees to help curb or reduce resource depletion, and enable resource gain, are worthy of more attention. For example, a family-supportive climate allows employees to take time to deal with family demands and creates psychological safety for employees to discuss their family concerns.

From the resource perspective, it would be interesting to explore whether resource loss is increasingly acute in the absence of resource gain. Therefore, it is worthwhile for future study to address how the interaction between FWC and FWE affects the overall amount of resources that employees have, which may in turn affect deviance.

Conclusion

Drawing on COR theory, this study investigates the effects of FI on interpersonal deviance at work through FWC and FWE. In addition, it also explores whether supervisor-level FSSBs moderate the indirect effects. We expect our study to make contributions to ethics literature and more specifically to the literature on deviant behaviors and incivility. Our study suggests FI as a form of mistreatment in the family domain has the potential to beget increasingly intense interpersonal mistreatment at work, thus providing insights on the family origins of workplace interpersonal deviance and extending the established notion of experienced incivility leading to instigated incivility (Naeem et al., 2020; Rosen et al., 2016). By integrating FWC and FWE processes, we reveal how a resource loss spiral and a disabled resource gain spiral account for the relationship between FI and interpersonal deviance. Lastly, we enrich an understanding of the boundary conditions of FI by identifying FSSBs as a supervisor-level macro resource that attenuates the adverse effects of FI, contributing to current knowledge about how organizations may provide a sTable resource to address the detrimental spillover effects caused by FI.

References

Aiken, L., & West, S. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage.

Allen, T. D., & Finkelstein, L. M. (2014). Work-family conflict among members of full-time dual-earner couples: An examination of family life stage, gender, and age. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 19(3), 376–384.

Andersson, L. M., & Pearson, C. M. (1999). Tit for tat? The spiraling effect of incivility in the workplace. Academy of Management Review, 24(3), 452–471.

Bai, Q., Lin, W., & Wang, L. (2016). Family incivility and counterproductive work behavior: A moderated mediation model of self-esteem and emotional regulation. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 94, 11–19.

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory (Vol. 1). ReCAPP.

Bennett, R. J., Marasi, S., & Locklear, L. (2018). Workplace deviance. Oxford University Press.

Bennett, R. J., & Robinson, S. L. (2000). Development of a measure of workplace deviance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(3), 349–360.

Bliese, P. D. (2000). Within-group agreement, non-independence, and reliability: Implications for data aggregation and analysis. In K. Klein & S. Kozlowski (Eds.), Multilevel theory, research, and methods in organizations: Foundations, extensions, and new directions (pp. 349–381). Jossey-Bass.

Braun, S., & Nieberle, K. W. A. M. (2017). Authentic leadership extends beyond work: A multilevel model of work-family conflict and enrichment. The Leadership Quarterly, 28(6), 780–797.

Brislin, R. W. (1986). The wording and translation of research instruments (Field methods in cross-cultural research). Sage.

Byron, K. (2005). A meta-analytic review of work–family conflict and its antecedents. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 67(2), 169–198.

Carlson, D. S., & Kacmar, K. M. (2000). Work-family conflict in the organization: Do life role values make a difference? Journal of Management, 26(5), 1031–1054.

Carlson, D. S., Kacmar, K. M., Wayne, J. H., & Grzywacz, J. G. (2006). Measuring the positive side of the work–family interface: Development and validation of a work–family enrichment scale. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 68(1), 131–164.

Chen, M., Liang, H., & Wang, T. (2020). Does family undermining influence workplace deviance? A mediated moderation model. Social Behavior & Personality: An International Journal, 48(9), 1–13.

Chen, Z., & Powell, G. N. (2012). No pain, no gain? A resource-based model of work-to-family enrichment and conflict. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 81(1), 89–98.

Cheng, K., Zhu, Q., & Lin, Y. (2021). Family-supportive supervisor behavior, felt obligation, and unethical pro-family behavior: The moderating role of positive reciprocity beliefs. Journal of Business Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-021-04765-9

Crain, T. L., & Stevens, S. C. (2018). Family-supportive supervisor behaviors: A review and recommendations for research and practice. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 39(7), 869–888.

De Clercq, D., Haq, I. U., Azeem, M. U., & Raja, U. (2018). Family incivility, emotional exhaustion at work, and being a good soldier: The buffering roles of waypower and willpower. Journal of Business Research, 89(8), 27–36.

De Clercq, D., Rahman, Z., & Haq, I. U. (2019). Explaining helping behavior in the workplace: The interactive effect of family-to-work conflict and Islamic work ethic. Journal of Business Ethics, 155(4), 1167–1177.

Den Hartog, D. N., & Belschak, F. D. (2012). Work engagement and machiavellianism in the ethical leadership process. Journal of Business Ethics, 107(1), 35–47.

Edwards, J. R., & Lambert, L. S. (2007). Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: A general analytical framework using moderated path analysis. Psychological Methods, 12(1), 1–22.

Ferguson, M., Carlson, D., Hunter, E. M., & Whitten, D. (2012). A two-study examination of work–family conflict, production deviance and gender. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 81(2), 245–258.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(3), 382–388.

Frone, M. R. (2003). Work-family balance. Handbook of occupational health psychology (pp. 143–162). American Psychological Association.

Goh, Z., Ilies, R., & Wilson, K. S. (2015). Supportive supervisors improve employees’ daily lives: The role supervisors play in the impact of daily workload on life satisfaction via work–family conflict. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 89, 65–73.

Gopalan, N., Pattusamy, M., & Goodman, S. (2021). Family incivility and work-engagement: Moderated mediation model of personal resources and family-work enrichment. Current Psychology, 1, 1–12.

Greenhaus, J. H., & Powell, G. N. (2006). When work and family are allies: A theory of work-family enrichment. Academy of Management Review, 31(1), 72–92.

Hakanen, J. J., Peeters, M. C. W., & Perhoniemi, R. (2011). Enrichment processes and gain spirals at work and at home: A 3-year cross-lagged panel study. Journal of Occupational & Organizational Psychology, 84(1), 8–30.

Hammer, L. B., Kossek, E. E., Bodner, T., & Crain, T. (2013). Measurement development and validation of the family supportive supervisor behavior short-form (FSSB-SF). Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 18(3), 285–296.

Hammer, L. B., Kossek, E. E., Yragui, N. L., Bodner, T. E., & Hanson, G. C. (2009). Development and validation of a multidimensional measure of family supportive supervisor behaviors (FSSB). Journal of Management, 35(4), 837–856.

Hammer, L. B., Kossek, E. E., Zimmerman, K., & Daniels, R. (2007). Clarifying the construct of family-supportive supervisory behaviors (FSSB): A multilevel perspective. In P. L. Perrewé, & D. C. Ganster (Eds.), Exploring the Work and Non-Work Interface (Vol. 6, pp. 165–204, Research in Occupational Stress and Well Being): Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. The American Psychologist, 44(3), 513–524.

Hobfoll, S. E. (1998). Stress, culture, and community: The psychology and philosophy of stress. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 44(5), 408–409.

Hobfoll, S. E. (2001). The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 50(3), 337–421.

Hobfoll, S. E. (2002). Social and psychological resources and adaptation. Review of General Psychology, 6(4), 307–324.

James, L. R., Demaree, R. G., & Wolf, G. (1993). rwg: An assessment of within-group interrater agreement. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78(2), 306–309.

Klein, K., & Kozlowski, S. (2000). Multilevel theory, research, and methods in organizations: Foundations, extensions, and new directions. San Francisco: Xxix, 605 Jossey-Bass.

Kossek, E. E., Pichler, S., Bodner, T., & Hammer, L. B. (2011). Workplace social support and work–family conflict: A meta-analysis clarifying the influence of general and work–family-specific supervisor and organizational support. Personnel Psychology, 64(2), 289–313.

Krischer, M. M., Penney, L. M., & Hunter, E. M. (2010). Can counterproductive work behaviors be productive? CWB as emotion-focused coping. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 15(2), 154–166.

Lee, K., & Allen, N. J. (2002). Organizational citizenship behavior and workplace deviance: The role of affect and cognitions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(1), 131–142.

Lim, S., & Lee, A. (2011). Work and nonwork outcomes of workplace incivility: Does family support help? Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 16(1), 95–111.

Lim, S., & Tai, K. (2014). Family incivility and job performance: A moderated mediation model of psychological distress and core self-evaluation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 99(2), 351–359.

Marescaux, E., Rofcanin, Y., Las Heras, M., Ilies, R., & Bosch, M. J. (2020). When employees and supervisors (do not) see eye to eye on family supportive supervisor behaviours: The role of segmentation desire and work-family culture. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 121, 103471.

Naeem, M., Weng, Q. D., Ali, A., & Hameed, Z. (2020). Linking family incivility to workplace incivility: Mediating role of negative emotions and moderating role of self-efficacy for emotional regulation. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 23(1), 69–81.

Netemeyer, R. G., Boles, J. S., & McMurrian, R. (1996). Development and validation of work-family conflict and family-work conflict scales. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81(4), 400–410.

O’Driscoll, M. P., Poelmans, S., Spector, P. E., Kalliath, T., Allen, T. D., Cooper, C. L., et al. (2003). Family-responsive interventions, perceived organizational and supervisor support, work-family conflict, and psychological strain. International Journal of Stress Management, 10(4), 326–344.

Pan, S. Y., Chuang, A., & Yeh, Y. J. (2021). Linking supervisor and subordinate’s negative work–family experience: The role of family supportive supervisor behavior. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 28(1), 17–30.

Peng, Y., Jex, S., Zhang, W., Ma, J., & Matthews, R. A. (2020). Eldercare demands and time theft: Integrating family-to-work conflict and spillover–crossover perspectives. Journal of Business and Psychology, 35(1), 45–58.

Podasakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903.

Porath, C. L., & Erez, A. (2007). Does rudeness really matter? The effects of rudeness on task performance and helpfulness. Academy of Management Journal, 50(5), 1181–1197.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2004). SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 36(4), 717–731.

Preacher, K. J., & Selig, J. P. (2012). Advantages of Monte Carlo confidence intervals for indirect effects. Communication Methods and Measures, 6(2), 77–98.

Raudenbush, S., & Bryk, A. (2002). Hierarchical linear models. SAGE.

Robinson, S. L., & Bennett, R. J. (1995). A typology of deviant workplace behaviors: A multidimensional scaling study. Academy of Management Journal, 38(2), 555–572.

Rosen, C. C., Koopman, J., Gabriel, A. S., & Johnson, R. E. (2016). Who strikes back? A daily investigation of when and why incivility begets incivility. Journal of Applied Psychology, 101(11), 1620–1634.

Seibert, S. E., Silver, S. R., & Randolph, W. A. (2004). Taking empowerment to the next level, a multiple-level model of empowerment, performance, and satisfaction. Academy of Management Journal, 47(3), 332–349.

Shockley, K. M., & Allen, T. D. (2013). Episodic work-family conflict, cardiovascular indicators, and social support: An experience sampling approach. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 18(3), 262–275.

ten Brummelhuis, L. L., & Bakker, A. B. (2012). A resource perspective on the work-home interface: The work-home resources model. American Psychologist, 67(7), 545–556.

ten Brummelhuis, L. L., ter Hoeven, C. L., Bakker, A. B., & Peper, B. (2011). Breaking through the loss cycle of burnout: The role of motivation. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 84(2), 268–287.

Venkatesh, V., Sykes, T. A., Chan, F. K. Y., Thong, J. Y. L., & Hu, P.J.-H. (2019). Children’s internet addiction, family-to-work conflict, and job outcomes: A study of parent–child dyads. MIS Quarterly, 43(3), 903–927.

Wayne, J. H., Casper, W. J., Matthews, R. A., & Allen, T. D. (2013). Family-supportive organization perceptions and organizational commitment: The mediating role of work–family conflict and enrichment and partner attitudes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 98(4), 606–622.

Wayne, J. H., Matthews, R., Crawford, W., & Casper, W. J. (2020). Predictors and processes of satisfaction with work–family balance: Examining the role of personal, work, and family resources and conflict and enrichment. Human Resource Management, 59(1), 25–42.

Wu, C., Chen, Y.-C., & Umstattd Meyer, M. R. (2020). A moderated mediation model of emotional labor and service performance: Examining the role of work–family interface and physically active leisure. Human Performance, 33(1), 34–51.

Xanthopoulou, D., Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2009). Reciprocal relationships between job resources, personal resources, and work engagement. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 74(3), 235–244.

Zhang, S., & Tu, Y. (2018). Cross-domain effects of ethical leadership on employee family and life satisfaction: The moderating role of family-supportive supervisor behaviors. Journal of Business Ethics, 152(4), 1085–1097.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by National Social Science Foundation of China (No. 21BGL143) and Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province of China (No. 2020J01032).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, L., Bai, Y. The Dual Spillover Spiraling Effects of Family Incivility on Workplace Interpersonal Deviance: From the Conservation of Resources Perspective. J Bus Ethics 184, 725–740 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-022-05123-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-022-05123-z