Abstract

Purpose

The use of adjuvant radiotherapy (RT) in the management of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) is increasing. Left-sided breast irradiation may involve exposure of the heart to ionising radiation, increasing the risk of ischemic heart disease (IHD). We examined the incidence of IHD in a population-based cohort of women with DCIS.

Methods

The Breast Cancer DataBase Sweden (BCBase) cohort includes women registered with invasive and in situ breast cancers 1992–2012 and age-matched women without a history of breast cancer. In this analysis, 6270 women with DCIS and a comparison cohort of 31,257 women were included. Through linkage with population-based registers, data on comorbidity, socioeconomic status and incidence of IHD was obtained. Hazard ratios (HR) for IHD with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were analysed.

Results

Median follow-up time was 8.8 years. The risk of IHD was not increased for women with DCIS versus women in the comparison cohort (HR 0.93; 95% CI 0.82–1.06), after treatment with radiotherapy versus surgery alone (HR 0.77; 95% CI 0.60–0.98) or when analysing RT by laterality (HR 0.85; 95% CI 0.53–1.37 for left-sided versus right-sided RT).

Conclusions

The risk of IHD was lower for women with DCIS allocated to RT compared to non-irradiated women and to the comparison cohort, probably due to patient selection. Comparison of RT by laterality did not show any over-risk for irradiation of the left breast.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The use of adjuvant radiotherapy (RT) in the management of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) has increased substantially over the last decades [1,2,3,4,5]. Four randomised trials have demonstrated that the addition of postoperative RT after breast conserving surgery (BCS) reduces ipsilateral breast events by half compared to surgery alone, but survival benefits remain uncertain [6,7,8,9]. In fact, in an overview of these trials by the Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaboration Group (EBCTCG), overall mortality and mortality from heart disease was slightly, although not statistically significant, higher in women allocated to RT [10].

Heart exposure to ionising radiation is associated with an increased risk of subsequent cardiovascular disease [11,12,13,14,15]. Modern radiation techniques have likely reduced the risk as the radiation dose to the heart from tangential RT has decreased considerably over the last 40 years [16]. The mean heart dose in left tangential RT has been estimated to be 13.3 Gy in the 1970s compared to 2.3 Gy in 2006 [17]. The anterior part of the heart may however still receive high doses [16] and studies imply an increased incidence of ischemic heart disease (IHD) after left-sided RT compared to right-sided RT, even with modern RT technique [13, 15, 18]. The causal effect of RT on heart disease appears to be mediated by radiation damage to the coronary arteries, in particular the left anterior descending artery, that leads to stenosis and myocardial ischemia [15, 19, 20].

Whereas women with invasive BC also may encounter cardiotoxic effects of systemic treatments, potentially increasing the risks, treatment for DCIS characteristically only involves surgery and RT. A few studies have examined radiation-related cardiovascular hazards in DCIS [10, 21,22,23,24,25]. In a recent publication, left-sided RT was found to be an independent risk factor for increased cardiac mortality from 1973 to 1982, but not after 1982 [24]. Cardiovascular morbidity was, however, not investigated. The only two studies examining both cardiovascular morbidity and mortality related to DCIS treatment did not show any excess incidence of heart disease [22, 23]. Still, these results need to be confirmed and it has been postulated that women with pre-existing cardiovascular risk factors may be more vulnerable to radiation exposure [14]. The aim of this study was to examine the risk of IHD in a large population-based cohort of women with DCIS given modern RT and a comparison cohort of age-matched women without a history of breast cancer (BC), adjusting for potential confounders of cardiac disease such as comorbidity and socioeconomic status.

Patients and methods

BCBase

In Sweden, regional registration of BC was started in the late 1970s to enable epidemiological surveillance of incidence, tumour characteristics, management and outcome. The registers in three of Sweden’s six health care regions have been merged, creating BCBase. These three regions altogether cover a source population of 5.2 million, representing about 50% of Sweden’s total population. All new invasive and in situ breast cancers diagnosed between 1992 and 2012 are included in the database. For the present study, the analyses included only women registered with DCIS. To this, a comparison cohort of women without BC has been added in a ratio of 5:1. Eligible for inclusion were women free of BC at the end of the year of diagnosis of the index case and born in the same year. Using the method of incidence density sampling, the women in the comparison cohort may have been selected for more than one case and were also allowed to become a case after the date of diagnosis of the index case. Using the unique personal identity number assigned to each Swedish resident, the database has been linked to a number of registers withheld by the National Board of Health and Welfare. The National Patient Register (NPR) has records of all hospital discharges in Sweden since 1987 and contains data on main diagnosis and up to eight secondary diagnoses. The register has been validated and is estimated to capture about 99% of all hospitalisations [26]. The NPR also contains hospital-based outpatient care since 2001. Classification of comorbidity was performed according to the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) using three comorbidity levels: 0 (no comorbidity), 1 (mild) and 2 (severe comorbidity) [27].

The Longitudinal Integration Database for Health Insurance and Labour Market Studies is an annually updated register integrating data from the labour market, the educational and social sectors. This register includes data on various socioeconomic variables for all residents in Sweden, such as marital status, income, place of employment (county, municipality) and highest level of education [28].

Statistics

IHD was defined by the International Classification of Disease (ICD) 9th edition codes 410-414 or ICD-10 codes I20-I25. Hazard ratios for risk of IHD were estimated by Cox proportional hazards regression analysis. Only events requiring a hospital admission were captured and only the first event recognised for each subject. Time at risk started at DCIS diagnosis and ended at date of IHD event, date of invasive breast cancer event in either the ipsilateral or the contralateral breast, death or end of the year of 2013, whichever came first. Risk of IHD was investigated by comparing women with DCIS to women in the comparison cohort, women with DCIS treated with surgery and RT to those having surgery alone and women receiving left-sided RT to those with right-sided RT. Risk estimates were adjusted for previous cardiovascular events, CCI and educational level. The CCI score was modified by removing IHD in order to avoid duplicate adjustment for this covariate. Cumulative incidence of IHD was calculated by the Kaplan–Meier method. Analyses were performed using the statistical software R [29].

Results

The study cohort consisted of 2978 women with right-sided DCIS and 3239 with left-sided DCIS, shown in Table 1. To this, 31,527 women without a history of either invasive or in situ breast cancer were added. Mean age at inclusion was 58.5 years and mean follow-up time was 8.8 years. The distributions of age at diagnosis and calendar period of diagnosis were similar for all three health care regions. Women with DCIS had a higher level of education compared to the women in the comparison cohort (32.9 vs. 28.1% in the highest level of education category) and they were generally healthier (89.9 vs. 88.7% with no comorbidity according to CCI score). Very few women in the DCIS group and the comparison cohort had a history of previous IHD events (2.7 and 3.1%, respectively). Of the women with DCIS, 38.9% received adjuvant RT (Table 2). Less than three per cent received adjuvant endocrine therapy which was expected as this is not recommended in Swedish treatment guidelines (not shown in table). Patient characteristics and treatment did not differ significantly between right- and left-sided DCIS.

Risk of IHD for women with DCIS

There were a total of 269 IHD events among women with DCIS and 1450 IHD events in the comparison cohort (Table 3). The risk of IHD was not increased for women with DCIS versus women in the comparison cohort (unadjusted HR 0.93; 95% CI 0.82–1.06 and adjusted HR 0.96; 95% CI 0.85–1.10). In the comparison of IHD risk in relation to treatment of DCIS (radiotherapy versus surgery alone) and using the comparison cohort as reference, the risk was lower for women receiving RT (HR 0.77; 95% CI 0.60–0.98) and at a very similar level after adjusting for CCI and educational level (HR 0.79; 95% CI 0.62–1.01).

Risk of IHD for women with DCIS by laterality

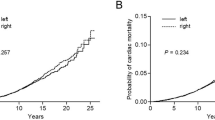

A comparison by laterality showed no increased risk of IHD from RT to the left breast (HR 0.85; 95% CI 0.53–1.37), not when comparing all women with DCIS, nor when comparing different types of surgery (Table 4). These results were not altered after adjusting for CCI and educational level (data not shown). The cumulative probability of IHD in women treated with adjuvant RT or surgery alone versus women without history of DCIS is visualised by a Kaplan–Meier analysis. Up to 16 years after treatment, the incidence of IHD for women with DCIS, whether irradiated or not, did not exceed that for the women in the comparison cohort (Fig. 1).

Discussion

In the present study, the incidence of IHD was not elevated for women with DCIS allocated to surgery and RT compared to surgery alone or to a comparison cohort of women without a history of BC. Adjustment for comorbidity and socioeconomic status did not alter the results. Furthermore, there was no statistically significant difference in IHD risk when comparing RT by laterality.

The finding that women with BC are healthier compared to the background female population is in concordance with other reports [18, 21, 23, 25]. Several explanations to this have been proposed. DCIS is largely detected through screening. A higher educational and socioeconomic status is thought to lead to a healthier lifestyle in general and women with a high educational level are more adherent to screening [30]. Women participating in screening are also more prone to use hormonal replacement therapy, and it has been hypothesised from observational studies that the intake of exogenous oestrogen may be protective against coronary heart disease [21, 31, 32]. Some risk factors for BC are supposedly protective of cardiovascular disease, for example, late menopause yielding a prolonged exposure of endogenous oestrogen. Results provided by more recent randomised trials have challenged these hypotheses though and suggest that oestrogen use does not confer any cardiac protection, rather it may even increase the risk [33]. Another hypothesis is that BC survivors tend to seek medical care more frequently [22], which can modulate their risk of coronary events.

The awareness of radiation-induced heart disease and the advent of new RT techniques have led to a substantial improvement in dose estimations to targets with reduced radiation exposure to the heart. Haque et al. compared cardiac mortality after RT between left- and right-sided DCIS and found no significant excess risk for women treated after 1982 [24]. Uncertainties about the duration of risk remain, as radiation-related mortality risks have been shown to be larger after 10–20 years after exposure than within the first decade [11, 12, 24, 34]. The only study that has shown a slight, although not statistically significant, elevated cardiac mortality in women receiving adjuvant RT in DCIS is the EBCTCG overview [10]. The overview includes randomised clinical trials, whereas in population-based studies, selection-bias needs to be considered, and accordingly risks may be underestimated. Comparison between left-sided and right-sided RT has therefore been the most accurate way to evaluate the cardiovascular risk [13, 35] .

The present study did not evaluate radiation-related cardiac mortality, but excess morbidity and more specifically increased IHD. Darby et al showed that the increase of IHD begins within the first 5 years of exposure [14]. No excess incidence of IHD over time in women irradiated for DCIS compared to surgery alone was found in the present study. Of the two studies specifically assessing the cardiac morbidity risk after treatment for DCIS, the first was rather small including only 129 patients [22]. The largest study, by Boekel et al, investigated both cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in 10,468 women with DCIS compared to the Dutch general population [23]. No excess risk of either cardiac morbidity or mortality was found and no difference in a comparison between left-sided and right-sided RT after a mean follow-up of 8 years, which is in line with our results [23]. Previous cardiovascular events were accounted for, but information on other cardiovascular risk factors were missing. In the present study, the registers included in BCBase allows for adjustment for concomitant comorbidity such as other cardiovascular diseases, pulmonary diseases and diabetes. We had no information on smoking, but could adjust the risk estimates by educational level which is highly correlated to smoking [36].

This study has several limitations. The number of events were limited leading to a lack of power to detect small or modest differences in morbidity due to IHD. Moreover, it may be that the median follow-up time of 8 years is too short to detect an excess cardiac morbidity. In a meta-analyses of long-term risks of coronary heart disease after RT, the risk increase started within the first 5 years and continued into the third decade after RT [15]. The highest relative risk occurred between 10 and 14 years after the diagnosis of BC. Another limitation is that as with all register studies, some misclassifications may be present. A validation of the BC register revealed that 7% of the women with registered DCIS actually had an invasive breast cancer [5]. However, there is no reason to believe that this would differ by laterality or that this low number would influence overall results. Finally, we had no information on individual radiation doses. National guidelines recommended RT by tangential field to the conserved breast in fractions of 2 Gy up to 50 Gy during 5 weeks. In a validation study, the accuracy of reported surgical and adjuvant treatment in the register was very high [5].

The strengths of the study include the population-based setting and the opportunity to make comparisons with women without DCIS from the same geographical area and of the same age distribution with available information on comorbidity and educational level. This should minimise bias of environmental risk factors for cardiovascular disease. The review and validation of the NPR showed a very high overall coverage and high accuracy of the diagnoses of myocardial infarction and angina pectoris [26]. Studying women with DCIS avoids the issue of systemic treatments that may alter the risk of cardiac morbidity, such as endocrine treatment, chemotherapy and HER-2 antibodies.

Improvements in BC survival have made it increasingly important to consider long-term adverse effects from adjuvant treatments. This is of particular importance for women with DCIS since adjuvant RT after BCS has not, as of yet, been shown to affect survival. The results of the present study are reassuring in that adjuvant RT with modern RT technique to the conserved breast after surgery for DCIS did not show any increase of IHD in the first 8 years of follow-up. Nevertheless, the use of RT in DCIS management is increasing. Even small increases in risk of IHD are thus of importance and longer follow-up of these women may be warranted.

References

Baxter NN, Virnig BA, Durham SB, Tuttle TM (2004) Trends in the treatment of ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. J Natl Cancer Inst 96:443–448. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djh069

Van Steenbergen LN, Voogd AC, Roukema JA et al (2014) Time trends and inter-hospital variation in treatment and axillary staging of patients with ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast in the era of screening in Southern Netherlands. Breast 23:63–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2013.11.001

Punglia RS, Schnitt SJ, Weeks JC (2013) Treatment of ductal carcinoma in situ after excision: would a prophylactic paradigm be more appropriate? J Natl Cancer Inst 105:1527–1533. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djt256

Worni M, Akushevich I, Greenup R et al (2015) Trends in treatment patterns and outcomes for ductal carcinoma in situ. J Natl Cancer Inst 107:djv263. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djv263

Wadsten C, Heyman H, Holmqvist M et al (2016) A validation of DCIS registration in a population-based breast cancer quality register and a study of treatment and prognosis for DCIS during 20 years: two decades of DCIS in Sweden. Acta Oncol 55:1338–1343. https://doi.org/10.1080/0284186X.2016.1211317

Emdin SO, Granstrand B, Ringberg A et al (2006) SweDCIS: radiotherapy after sector resection for ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. Results of a randomised trial in a population offered mammography screening. Acta Oncol Stockh Swed 45:536–543. https://doi.org/10.1080/02841860600681569

Houghton J (2003) Radiotherapy and tamoxifen in women with completely excised ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast in the UK, Australia, and New Zealand: randomized controlled trial. Lancet Br Ed 362:95–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13859-7

Fisher B, Costantino J, Redmond C et al (1993) Lumpectomy compared with lumpectomy and radiation therapy for the treatment of intraductal breast cancer. N Engl J Med 328:1581–1586. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199306033282201

Julien JP, Bijker N, Fentiman IS et al (2000) Radiotherapy in breast-conserving treatment for ductal carcinoma in situ: first results of the EORTC randomised phase III trial 10853. EORTC Breast Cancer Cooperative Group and EORTC Radiotherapy Group. Lancet 355:528–533

Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTCG), Correa C, McGale P, et al (2010) Overview of the randomized trials of radiotherapy in ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 2010:162–177. https://doi.org/10.1093/jncimonographs/lgq039

Cuzick J, Stewart H, Rutqvist L et al (1994) Cause-specific mortality in long-term survivors of breast cancer who participated in trials of radiotherapy. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol 12:447–453

Clarke M, Collins R, Darby S et al (2005) Effects of radiotherapy and of differences in the extent of surgery for early breast cancer on local recurrence and 15-year survival: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet 366:2087–2106. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67887-7

McGale P, Darby SC, Hall P et al (2011) Incidence of heart disease in 35,000 women treated with radiotherapy for breast cancer in Denmark and Sweden. Radiother Oncol 100:167–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radonc.2011.06.016

Darby SC, Ewertz M, McGale P et al (2013) Risk of ischemic heart disease in women after radiotherapy for breast cancer. N Engl J Med 368:987–998. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1209825

Cheng Y, Nie X, Ji C et al (2017) Long-term cardiovascular risk after radiotherapy in women with breast cancer. J Am Heart Assoc 6:e005633. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.117.005633

Taylor CW, Povall JM, McGale P et al (2008) Cardiac dose from tangential breast cancer radiotherapy in the year 2006. Int J Radiat Oncol 72:501–507. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.12.058

Taylor CW, Nisbet A, McGale P, Darby SC (2007) Cardiac exposures in breast cancer radiotherapy: 1950s–1990s. Int J Radiat Oncol 69:1484–1495. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.05.034

Harris EER, Correa C, Hwang W-T et al (2006) Late cardiac mortality and morbidity in early-stage breast cancer patients after breast-conservation treatment. J Clin Oncol 24:4100–4106. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2005.05.1037

Correa CR, Litt HI, Hwang W-T et al (2007) Coronary artery findings after left-sided compared with right-sided radiation treatment for early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 25:3031–3037. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2006.08.6595

Nilsson G, Holmberg L, Garmo H et al (2012) Distribution of coronary artery stenosis after radiation for breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 30:380–386. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2011.34.5900

Ernster VL, Barclay J, Kerlikowske K et al (2000) Mortality among women with ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast in the population-based surveillance, epidemiology and end results program. Arch Intern Med 160:953–958

Park CK, Li X, Starr J, Harris EER (2011) Cardiac morbidity and mortality in women with ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast treated with breast conservation therapy: cardiac risk post-radiation in DCIS. Breast J 17:470–476. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-4741.2011.01122.x

Boekel NB, Schaapveld M, Gietema JA et al (2014) Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality after treatment for ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. J Natl Cancer Inst 106:dju156. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/dju156

Haque W, Verma V, Haque A et al (2017) Trends in cardiac mortality in women with ductal carcinoma in situ. Breast Cancer Res Treat 161:345–351. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-016-4045-z

Elshof LE, Schmidt MK, Rutgers EJT et al (2017) Cause-specific mortality in a population-based cohort of 9799 women treated for ductal carcinoma in situ. Ann Surg. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000002239

Ludvigsson JF, Andersson E, Ekbom A et al (2011) External review and validation of the Swedish national inpatient register. BMC Public Health 11:450. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-450

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR (1987) A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 40:373–383

Startsida. In: Stat. Cent. http://www.scb.se/. Accessed 25 May 2015

R Core Team (2017) R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Found. Stat. Comput. Vienna Austria. https://www.R-project.org/

Damiani G, Basso D, Acampora A et al (2015) The impact of level of education on adherence to breast and cervical cancer screening: evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev Med 81:281–289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.09.011

Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Willett WC et al (1991) Postmenopausal estrogen therapy and cardiovascular disease: ten-year follow-up from the nurses’ health study. N Engl J Med 325:756–762. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199109123251102

Grady D (1992) Hormone therapy to prevent disease and prolong life in postmenopausal women. Ann Intern Med 117:1016. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-117-12-1016

Manson JE, Hsia J, Johnson KC et al (2003) Estrogen plus progestin and the risk of coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med 349:523–534. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa030808

Henson KE, McGale P, Taylor C, Darby SC (2013) Radiation-related mortality from heart disease and lung cancer more than 20 years after radiotherapy for breast cancer. Br J Cancer 108:179–182. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2012.575

Darby SC, McGale P, Taylor CW, Peto R (2005) Long-term mortality from heart disease and lung cancer after radiotherapy for early breast cancer: prospective cohort study of about 300,000 women in US SEER cancer registries. Lancet Oncol 6:557–565. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70251-5

Cavelaars AE, Kunst AE, Geurts JJ et al (2000) Educational differences in smoking: international comparison. BMJ 320:1102–1107

Funding

The study was funded by grants from The Swedish Breast Cancer Association (BRO), Vasterbotten County Council (VLL) and the Dept of Research and Development Vasternorrland County Council.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the regional committee of ethics in Stockholm, reference number 2013/1272-31/4 and with the 164 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

For this type of study informed consent is not required.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Wadsten, C., Wennstig, AK., Garmo, H. et al. Risk of ischemic heart disease after radiotherapy for ductal carcinoma in situ. Breast Cancer Res Treat 171, 95–101 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-018-4803-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-018-4803-1