Abstract

Purpose

The second International Consensus Conference on B3 lesions was held in Zurich, Switzerland, in March 2018, organized by the International Breast Ultrasound School to re-evaluate the consensus recommendations.

Methods

This study (1) evaluated how management recommendations of the first Zurich Consensus Conference of 2016 on B3 lesions had influenced daily practice and (2) reviewed current literature towards recommendations to biopsy.

Results

In 2018, the consensus recommendations for management of B3 lesions remained almost unchanged: For flat epithelial atypia (FEA), classical lobular neoplasia (LN), papillary lesions (PL) and radial scars (RS) diagnosed on core-needle biopsy (CNB) or vacuum-assisted biopsy (VAB), excision by VAB in preference to open surgery, and for atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH) and phyllodes tumors (PT) diagnosed at VAB or CNB, first-line open surgical excision (OE) with follow-up surveillance imaging for 5 years. Analyzing the Database of the Swiss Minimally Invasive Breast Biopsies (MIBB) with more than 30,000 procedures recorded, there was a significant increase in recommending more frequent surveillance of LN [65% in 2018 vs. 51% in 2016 (p = 0.004)], FEA (72% in 2018 vs. 62% in 2016 (p = 0.005)), and PL [(76% in 2018 vs. 70% in 2016 (p = 0.04)] diagnosed on VAB. A trend to more frequent surveillance was also noted also for RS [77% in 2018 vs. 67% in 2016 (p = 0.07)].

Conclusions

Minimally invasive management of B3 lesions (except ADH and PT) with VAB continues to be appropriate as an alternative to first-line OE in most cases, but with more frequent surveillance, especially for LN.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lesions of uncertain malignant potential in the breast (B3 lesions) represent a heterogeneous group of abnormalities with an overall risk for malignancy of 9.9%–35.1% after total resection [1]. Historically open surgical excision has been recommended for all B3 lesions; however, over the last decade there has been a trend towards minimally invasive breast biopsy or percutaneous excision using a vacuum-assisted device where larger volumes of tissue can be removed compared to core biopsy, equivalent to a small-wide local excision while retaining the same diagnostic accuracy as open surgery [2], but with the obvious benefits of saving the patient a surgical procedure, and cost. Underestimates of malignancy in excised B3 lesions range up to 35% and are associated primarily with increasing size of the lesion and the presence of atypia rather than the nature of the mammographic abnormality (e.g., calcification vs. mass or architectural distortion) [3]. Several studies also indicate that B3 lesions are predominantly upgraded to ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) and low-grade invasive tumors [1, 3,4,5,6].

The evidence base for the outcome and behavior of B3 lesions in the literature is accruing. Management and practice vary greatly from country to country, although there is a trend universally for more conservative management as an alternative to open surgery. The 2016 recommendations from the first International Consensus Conference on B3 lesions [7] during the biannual International Breast Ultrasound School (IBUS) course were well accepted by many breast units in different countries. The purpose of the second International Consensus Conference in 2018 was to re-evaluate how recommendations for the management and follow-up surveillance of B3 lesions in the breast had influenced daily practice, review the most recent literature, and investigate the trend towards less open surgery and appropriate surveillance.

Methodology

The second International Consensus Conference on lesions of uncertain malignant potential (B3) was held with international experts as part of the IBUS seminar in March 2018. The meeting in March 2018 had 70 participants with an additional 19 multidisciplinary expert panel members (including all the aforementioned authors) comprising 55% radiologists, and 45% other (including pathologists, surgeons, and gynecologists) with 68% having more than 10 years’ experience in breast imaging. All participants were invited to vote on all recommendations and between 60 and 80 (depending on the question asked) decided to vote.

A new analysis of the Swiss Minimally Invasive Breast Biopsy group (MIBB) Database was performed and presented (histology from 31,574 VABs). The Swiss MIBB group—a subgroup of the Swiss Society of Senology founded in 2007—has collected data for 11 years on each diagnostic or therapeutic VAB performed in Switzerland. To evaluate the impact of the B3 guidelines from the first International Consensus Conference in the management and surveillance of B3 lesions, the data were compared between 2007 and 2015 and 2016–2017 using the Chi-squared test.

Recommendations for management of B3 breast lesions following histological diagnosis were either (i) surveillance (defined as 6 monthly or yearly mammography and/or ultrasound, depending on their imaging findings), (ii) VAB excision, or (iii) open excision.

Following presentations of each B3 lesion in detail with an update of the published literature since the first International Consensus Conference, three questions were asked in turn regarding each of the six B3 lesions [8]:

-

Q1.

If a core-needle biopsy (CNB) returned a B3 lesion on histology, should the lesion be excised?

-

Q2.

If so, should it be excised using vacuum-assisted biopsy (VAB) or open surgical excision (OE)?

-

Q3.

If the VAB returned a B3 lesion on histology and if the lesion was completely removed on imaging, is surveillance acceptable or should a repeat VAB or OE be performed?

A panel discussion followed the voting and consensus recommendations were agreed for the management of each B3 lesion along with decisions on surveillance.

Results

Analysis of the MIBB database

From 2007 until 2017, a total of 31,574 VABs were entered in the database. 6,020 cases (19.1%) showed a B3 lesion (4339 were pure and the other ones were combined B3 lesions).

Table 1 shows the pure B3 lesions together with the final histology in those which had a subsequent open surgery and upgrade rates.

Table 2 shows recommendations made to the patients following VAB. Between 2016 and 2017, surveillance was recommended more frequently for all B3 lesions following VAB, but this was only significant for the following lesions: FEA (72% vs. 61.5%: p = 0.005), LN (64.9% vs. 51%; p = 0.004), and PLs (76% vs. 69.7%; p = 0.04).

General recommendations of the panel members of the consensus conference

Acceptable rates for the risk of underestimation

In 2016, the panel of the first International Consensus Conference on B3 lesions stated that every B3 lesion should be discussed at a multidisciplinary meeting (MDM). If an MDM makes the decision not to perform open surgery after a diagnosis of a B3 lesion following VAB, it means balancing risks (e.g., having to undergo a surgery under anesthesia which produces a scar) and benefits (e.g., not risking underestimating a lesion, which could be or develop towards an invasive cancer). Therefore in 2018, the question asked was: What is an acceptable underestimation rate for DCIS or IC?

69 participants gave answers for upgrade to IC: < 2.5%: 36 (53%); < 5%: 23 (34%); < 7.5%: 8 (12%); and < 10%: 2 (3%).

68 participants gave answers for upgrade to DCIS: < 5%: 15 (22%); < 10%: 40 (59%); < 15%: 9 (13%); and < 20%: 4 (6%). Therefore, overall underestimation rates for the majority of the panel members were that it should not exceed 5% for IC and 10% for DCIS.

Reasons for recommending an open biopsy instead of surveillance

The panel also discussed which circumstances would argue for performing an open biopsy instead of surveillance only. Discrepancy between histology and imaging was by far the most important factor. For example, if a solid lesion and not only microcalcifications are seen, then histology should correspond to this finding. Further strong arguments for performing a subsequent open biopsy or a repeat VAB were a residual lesion and lesion size. The larger a lesion is, the more likely an open biopsy should be recommended. For an ultrasound-guided VAB, the size should usually not exceed 2.5 cm. Elevated personal risk, the presence of a solid lesion on ultrasound, associated calcifications within the lesion, and absence of calcifications within the lesion were also considered.

Recent literature

Recent manuscripts dealing with B3 lesions were selected for presentation and discussion at the conference. Many of the papers document upgrade rates in following open excision and the risk of developing a cancer during the years following a diagnosis of a B3 lesion. In some of the manuscripts, CNB and VAB were not well differentiated. CNB, often also called microbiopsy, should be used for CNB performed with devices smaller or equal to 14G. The term VAB, often called macrobiopsy, would therefore be reserved for larger needle devices (typically 7 to 11G). Since upgrade rates depend on the amount of tissue, which is available for the pathologist for examination, this distinction is important.

Atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH)

Histological criteria of ADH

ADH is a low-grade neoplastic intraductal proliferation. The histological criteria of ADH include quantitative features of low-grade atypia as monomorphic nuclei with clear membranous borders and secondary intraluminal adenoid architecture. As quantitative features, restriction to one terminal ductal-lobular unit (TDLU) is usually ≤ 2 mm in maximal extension, whereas the histological as immunophenotypical features of an ADH lesion are the same as at low-grade DCIS. Intraductal ADH cell proliferations are negative for high molecular weight cytokeratins and strongly and diffusely positive for estrogen receptors in the same pattern as seem at low-grade DCIS. The differential diagnosis between ADH and DCIS is based on size only. Therefore, a low-grade in situ neoplastic lesion with qualitative features of ADH cannot definitely be separated from a part of a larger low-grade DCIS based on findings in minimal invasive breast biopsy (CNB or VAB) alone. The European Working Group on Breast Screening Pathology recommends that it should always be kept in mind that such proliferations at a biopsy may represent the periphery of a more established lesion of DCIS [9].

Underestimation risk associated with ADH at VAB

The dilemma in decision making on management of an ADH-like lesion at MIBB is the uncertainty whether it represents a part of a larger DCIS or is an isolated lesion. There is only limited information on histological, imaging, and clinical factors, which can reliably predict the answer. These include lesion size and number of ADH foci in biopsy specimens, radiological features, needle type, and association with calcification and individual cell necrosis. Until now, none of these features can reliably exclude an upgrade in the surgical specimen. However, risk factors for underestimation of malignancy include multifocality with more than 2 foci of ADH on CNB, and associated individual cell necrosis, this latter might be suggestive but definitely not affirmatively diagnostic of a low-grade DCIS. In addition, lack of radiological-pathological correlation as lack of calcification in MIBB specimens on VAB performed for mammographically suspicious calcifications as well as ADH-like lesions as only histopathological finding in biopsies taken for mass lesions on imaging. Conflicting results of several studies analyzing the risk factors of synchronous malignancy in MIBB with ADH published in recent years as the large range of their underestimation rates (2%–50%), as summarized in Table 3, seems to be depending on the type of biopsy performed (CNB or VAB), age (> 50 years), and on associated microcalcification on imaging. But above all, upgrade rates are generally higher in biopsies without any pathological correlation to the target lesion in imaging. Table 3 summarizes the literature update on ADH since 2015.

Since upgrade rates in so-called lower-risk subgroups exceed the defined acceptable limits for underestimation (10% for DCIS and 5% for IC), OE is recommended in general even if the lesion seems to be completely excised by VAB. Surveillance instead of OE might be appropriate in special situations (especially in older age) since most of the IC that develop after ADH are small low-grade cancers. Surveillance is also necessary after OE because such patients are at a higher risk of developing cancer also distant from the excised ADH lesion and also in the contralateral breast.

Voting

If a CNB returned ADH on histology,

100% of the participants thought the lesion should be excised. 21% thought therapeutic VAB excision was acceptable and 74% thought therapeutic open surgical excision should be performed. 5% were undecided.

If a VAB returned ADH on histology,

51% of the participants thought that therapeutic open surgical excision should be performed and 42% thought that surveillance was adequate (Table 9).

Consensus recommendation of the panel

A lesion containing ADH diagnosed by CNB or VAB should undergo open surgical excision. Surveillance can be justified only in special situations after discussion at the MDM (Table 10).

Flat epithelial atypia (FEA)

Histological criteria of FEA

FEA is a low-grade neoplastic lesion consisting of a few layers of neoplastic columnar type cells with low-grade (monomorphic) atypia without any secondary architecture (flat architecture). The immunophenotype of a FEA lesion is identical to that of a low-grade DCIS, which is negative for basal cytokeratins and positive for estrogen receptors. On histology, there is a classical association with low-grade or highly differentiated lesions as highly differentiated invasive carcinoma, ADH/DCIS, and to the other B3 lesions as classical LN. There are often associated calcifications and, therefore FEA is sometimes the only biopsy target at mammography.

Biology of FEA

FEA seems to be associated with a very slight increased breast cancer risk (1–2 times). Underestimation of risk is associated with ADH at MIBB.

Lesions found after FEA on breast core-needle CNB and VAB are mainly ADH and low-grade DCIS, while invasive carcinoma (in most instances highly differentiated) can occur but less frequent. Recommendation of current guidelines is increasingly in favor of surveillance if the lesion is small and the radiological findings were completely removed by CNB or VAB. Table 4 summarizes the literature update on FEA since 2015.

Voting

If a CNB returned FEA on histology,

65% of the participants thought the lesion should be excised. 75% thought therapeutic VAB excision was acceptable and 22% thought therapeutic open surgical excision should be performed.

If a VAB returned FEA on histology,

3% of the participants thought that therapeutic open surgical excision should be performed and 97% thought that surveillance was adequate (Table 9).

Consensus recommendation of the panel

A lesion containing FEA which is visible on imaging should undergo excision with VAB. Thereafter surveillance is justified (Table 10).

Classical lobular neoplasia

Histological criteria

Lobular neoplasia (LN) includes a large spectrum and continuum of atypical intralobular proliferations of the TDLs of the breast, consisting of non-cohesive proliferating cells. Under the term “Classical Lobular Neoplasia,” the consensus conference discussed the two lesions defined by the WHO classification as classical lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS) and atypical lobular hyperplasia (ALH), both of which represent the large majority of lobular neoplasia. ALH/LCIS are characterized by non-cohesive proliferations of atypical type A and/or B epithelial cells with mild-to-moderate nuclear atypia in about 85% of cases [33]. In case of LCIS, these cells expand more than 50% of the acini in a terminal duct-lobular unit (TDLU), while in ALH this affects less than 50%. When diagnosed on minimal invasive biopsy (VAB), these lesions are reported as B3 by the pathologist. In case of diagnostic difficulty in the histological diagnosis, the use of a combined immunohistochemistry with E-Cadherin and Catenin p120 is useful to rule out morphological differential diagnoses especially as solid DCIS.

In contrast, the rare morphologic variants including pleomorphic LN which demonstrates marked nuclear pleomorphism equivalent to that of high-grade ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), with or without apocrine features. A florid LN along with marked distention of TDLUs or ducts, often with accompanying mass formation and comedo type necrosis, are reported as B5a as DCIS and are not discussed as LN in this consensus report. The underlying rationale is that in contrast to LCIS and ALH, 25–60% of cases with LN (B5a category) variants on CNB/VAB are found to upgrade to carcinoma on excision [34,35,36]. The reproducibility of all LIN ALH versus LCIS is poor, the prognostic significance between LIN1,2 is not supported by evidence, so it is not endorsed by current European guidelines (AGO [37]). It is a simplified and practical way to categorize these lesions as B3 (e.g., as classical LN) and B5a (as pleomorphic or florid LN) especially on CNB and VAB.

Biological behavior

ALH/LCIS has to be considered as both, a risk factor and a non-obligate precursor of invasive breast carcinoma conferring an 8 to 10 times relative risk compared to the general population [38, 39]. The absolute risk of either lobular or ductal breast cancer is in the range of 1–2% per year with a cumulative long-term rate of more than 20% at 15 years and 35% at 35 years [39, 40]. The risk is bilateral with ipsilateral predominance [41, 42].

Until now, no single histopathological or clinical factor alone has been identified which could link the development of breast cancer to a histological diagnosis of classical LN.

Risk of breast cancer at CNB/VAB

The management of patients with classic LN when diagnosed on MIBB (CNB/VAB) has been controversial due to a wide range (0–60%) of reported upgrade rates to DCIS or invasive carcinoma on excision. Those rates result above all from disregarding radiological–pathological correlation [43,44,45,46]. LCIS and ALH are infrequently seen as the sole finding in CNB or VAB accounting for 0.5–2.9% of biopsies taken for histologic assessment of mammography-detected lesions. Therefore, recent studies of classic LCIS and ALH as incidental finding in cases where a different benign pathological lesion in the same biopsy has been proved to represent the correlation to the radiological biopsy target with concordant imaging findings report very low (~ 1–4%) excisional upgrade rates of classic LCIS and ALH to carcinoma. Regarding ALH, the largest study showed a relative risk of 8.0 for women with 3 or more foci of ALH compared to 3 or 5 for women with 1 or 2 foci, respectively. The upgrade rates for classical LCIS are generally higher (13% to 18%) when LCIS represented the radiologic target as calcification and still higher for mass lesions and calcification on imaging with radio-pathological discordance [47,48,49]. Current (AGO [37]) guidelines in favor of surgical management of classical LN include the presence of another B3 lesion, another lesion indicative for excision alone, the presence of a visible or mass lesion or any discordant lesions between histology and imaging (AGO [37]). Table 5 summarizes the literature update on classical LN in CNB/VAB since 2015.

Voting

If a CNB returned Classical LN on histology,

69% of the participants thought the lesion should be excised. 50% thought therapeutic VAB excision was acceptable and 41% thought therapeutic open surgical excision should be performed.

If a VAB returned Classical LN on histology,

12% of the participants thought that therapeutic open surgical excision should be performed and 84% thought that surveillance was adequate (Table 9).

Consensus recommendation of the panel

A lesion containing classical LN, which is visible on imaging should undergo excision with VAB. Thereafter surveillance is justified if there is no pathological–radiological discordance and no residual lesion.

In contrast, morphologic variants of LN (LIN 3, pleomorphic LCIS, and florid LCIS), which are reported as B5a lesions should undergo OE (Table 10).

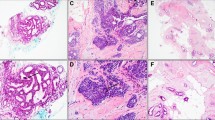

Papillary lesions

Histology and clinical presentation of PL

On imaging, intraductal papillomas vary in size and in presentation showing a spectrum of mass lesions to cystic and calcified lesions. Histology demonstrates a papillary proliferation as the basis with a central fibrovascular core containing ductal and myoepithelial cells. In case of any histological uncertainty regarding the presence of myoepithelial cells, the use of immunohistochemistry (p 63, basal cytokeratins, and estrogen receptors) is helpful. In the current WHO classification of breast tumors, papillary lesions are divided into (a) papillomas, (b) papillomas with atypia (ADH or classical LN), both belonging to the B3 category at MIBB (small solitary papillomas (< 2 mm) can be categorized as B2 lesion, if the lesion is completely surrounded by a duct structure) and to (c) papillomas with DCIS or papillomas completely involved by more extended DCIS (encapsulated papillary carcinoma), and finally (d) solid papillary carcinoma belonging to B4 or B5a category. Table 6 summarizes the literature update on B3 papillary lesions since 2015.

Voting

If a CNB returned PL on histology,

76.5% of the participants thought the lesion should be excised. 71% thought therapeutic VAB excision was acceptable and 23% thought therapeutic open surgical excision should be performed.

If a VAB returned PL on histology,

none of the participants (1 abstained) thought that therapeutic open surgical excision should be performed and 98% thought that surveillance was adequate (Table 9).

Consensus recommendation of the panel

A PL lesion, which is visible on imaging should undergo excision with VAB. Larger lesions which cannot be completely removed by VAB need open excision. Thereafter surveillance is justified (Table 10).

Phyllodes tumors (PT)

Histological criteria and biological behavior of PT

PTs are rare and consist of around 1–2‰ of all breast biopsies. PTs are biphasic fibroepithelial tumors varying from benign to borderline and malignant diagnostic variants. The latest WHO classification of breast tumors allows three categories depending on the number of stromal mitoses, stromal atypia, and stromal overgrowth. In some cases, the distinction between a benign cellular fibroadenoma and a benign phyllodes tumors remains despite histological diagnostic criteria problematic. Therefore, the WHO classification recommends the diagnosis of a benign fibroepithelial tumor (also categorized as B3 category) in unclear cases. Benign and borderline phyllodes tumors are B3 lesions, a malignant PT is a B5b lesion. B3 forms, particularly the benign forms of PT, are the most common, only up to 20% of all PT tumors are borderline or malignant. Risk for local recurrence at benign PT is around 10–20% and reaches up to 30% at the borderline or malignant forms. Metastatic potential depends on the form, being the highest (15–20%) at the malignant forms. Table 7 summarizes the literature update on B3 phyllodes tumors since 2015.

Voting

If a CNB returned PT on histology,

98% of the participants thought the lesion should be excised. 22% thought therapeutic VAB excision was acceptable and 72% thought therapeutic open surgical excision should be performed.

If a VAB returned PT on histology,

8% of the participants thought that therapeutic open surgical excision should be performed and 88% thought that surveillance was adequate (Table 9).

Consensus recommendation of the panel

A PT lesion, which is found by CNB, should undergo open surgical excision with clear margins. If accidentally found by VAB without any corresponding imaging finding, surveillance of a benign PT is justified, while borderline and malignant PTs require re-excision to obtain clear margins (Table 10).

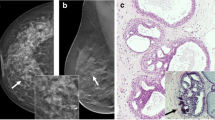

Radial scar

Histological features of RS

Two papers published almost at the same time described the same lesion naming that was named radial scar by Hamperl [79] and scleroelastotic lesion by Eusebi et al. [80]. More recently, the definition of complex sclerosing lesion (CSL) has been proposed. RS is characterized by a central area mimicking a scar, containing one to several ducts showing obliterative mastopathy, and surrounded by elastic fibers. In addition, other ducts converge into the scar-like area in a stellate fashion. The epithelium lining the latter ducts may show a great variety of changes, the most frequent being benign epitheliosis (usual ductal hyperplasia). The central scar-like area together with stellate appearance of the outer ducts easily mimics an invasive carcinoma, both on radiological and histological grounds. RS can be detected during screening mammography and now even more often by tomosynthesis, therefore sampled by CNB or by VAB. There is general agreement that RS alone is a benign lesion, but RS can be occasionally associated with carcinoma. When RS is associated to atypia (such as flat epithelial atypia (FEA), atypical ductal (ADH), or lobular neoplasia (classical LN)), management can the same as recommended in cases of atypia alone. Management is more controversial in cases without atypical lesions. In these cases, upgrade of cancers is associated with architectural distortions and larger masses (≥ 10 mm), calcifications, and older age [69, 71]. The recently published data suggest that in cases of RS diagnosed using CNB or VAB, it must be taken into consideration that (a) accurate and detailed radiological–pathological correlations must be obtained; (b) lesions < 10 mm have lower rate of cancer upgrading; (c) histology is vital in the evaluation of presence or absence of atypical features within the lesion. Table 8 summarizes the literature update on radial scar since 2015.

Voting

If a CNB returned RS/CSL on histology,

85% of the participants thought the lesion should be excised. 72% thought therapeutic VAB excision was acceptable and 26% thought therapeutic open surgical excision should be performed.

If a VAB returned RS/CSL on histology,

2% of the participants thought that therapeutic open surgical excision should be performed and 98% thought that surveillance was adequate (Table 9).

Consensus recommendation of the panel

A RS/CSL lesion, which is visible on imaging should undergo therapeutic excision with VAB. Thereafter surveillance is justified (Table 10).

Tables 9 and 10 show the summaries of the votings and the recommendations for each B3 lesion.

Discussion

The panel agreed that underestimation rates should be below 5% for IC and below 10% for DCIS. If a certain B3 lesion shows an upgrade rate of more than 10%, in general surveillance was not recommended. Computer-aided decision making would be of interest. Bahl et al. [91] show the potential of machine learning methodology in the field of high-risk breast lesions predicting the risk of upgrade (editorial by Shaffer [92]).

Other recommendations [93, 94] favor recommendations from the consensus meetings. They do not explicitly propose VAB as we do, probably due to the fact, that VAB is not so well established in other countries yet.

The 2018 recommendations confirm largely the 2016 recommendations. Results presented in the recent literature confirm the 2016 recommendations for surveillance after a B3 lesion diagnosed by VAB or CNB, especially for FEA, RS, PL, and PT. Upgrade rates are high in ADH and in LN which are not only focal or an incidental finding especially if pathological–radiological concordance is not given. LN lesions with pleomorphic, extended features, and LN with necrosis should be reported as B5a lesions and should undergo OE as DCIS. Our recommendations for ADH are slightly less liberal in 2018 than in 2016 and tend more towards OE.

Change history

31 May 2019

The article Second International Consensus Conference on lesions of uncertain malignant potential in the breast (B3 lesions), written by Christoph J Rageth, Elizabeth AM O’Flynn, Katja Pinker, Rahel A Kubik-Huch, Alexander Mundinger, Thomas Decker, Christoph Tausch, Florian Dammann, Pascal A. Baltzer, Eva Maria Fallenberg, Maria P Foschini, Sophie Dellas, Michael Knauer, Caroline Malhaire, Martin Sonnenschein, Andreas Boos, Elisabeth Morris, Zsuzsanna Varga, was originally published electronically on the publisher’s internet portal (currently SpringerLink) on November 30, 2018 without open access.

References

Bianchi S, Caini S, Renne G, Cassano E, Ambrogetti D, Cattani MG, Saguatti G, Chiaramondia M, Bellotti E, Bottiglieri R et al (2011) Positive predictive value for malignancy on surgical excision of breast lesions of uncertain malignant potential (B3) diagnosed by stereotactic vacuum-assisted needle core biopsy (VANCB): a large multi-institutional study in Italy. Breast 20(3):264–270

O’Flynn EA, Wilson AR, Michell MJ (2010) Image-guided breast biopsy: state-of-the-art. Clin Radiol 65(4):259–270

Houssami N, Ciatto S, Ellis I, Ambrogetti D (2007) Underestimation of malignancy of breast core-needle biopsy: concepts and precise overall and category-specific estimates. Cancer 109(3):487–495

Renshaw AA, Gould EW (2016) Long term clinical follow-up of atypical ductal hyperplasia and lobular carcinoma in situ in breast core needle biopsies. Pathology 48(1):25–29

Strachan C, Horgan K, Millican-Slater RA, Shaaban AM, Sharma N (2016) Outcome of a new patient pathway for managing B3 breast lesions by vacuum-assisted biopsy: time to change current UK practice? J Clin Pathol 69(3):248–254

El-Sayed ME, Rakha EA, Reed J, Lee AH, Evans AJ, Ellis IO (2008) Predictive value of needle core biopsy diagnoses of lesions of uncertain malignant potential (B3) in abnormalities detected by mammographic screening. Histopathology 53(6):650–657

Rageth CJ, O’Flynn EA, Comstock C, Kurtz C, Kubik R, Madjar H, Lepori D, Kampmann G, Mundinger A, Baege A et al (2016) First International Consensus Conference on lesions of uncertain malignant potential in the breast (B3 lesions). Breast Cancer Res Treat 159(2):203–213

Perry N, Broeders M, de Wolf C, Tornberg S, Holland R, von Karsa L (2008) European guidelines for quality assurance in breast cancer screening and diagnosis. Fourth edition-summary document. Ann Oncol 19(4):614–622

Wells CA, Amendoeira I, Bellocq JP, Bianchi S, Boecker W, Borisch B, Bruun Rasmussen B, Callagy GM, Chmielik E, Cordoba A, Cserni G, Decker T, DeGaetano J, Drijkoningen M, Ellis IO, Faverly DR, Foschini MP, Frkovic-Grazio S, Grabau D, Heikkilä P, Iacovou E, Jacquemier J, Kaya H, Kulka J, Lacerda M, Liepniece-Karele I, Martinez-Penuela J, Quinn CM, Rank Ft, Regitnig P, Reiner A, Sapino A, Tot T, Van Diest PJ, Varga Z, Wesseling J, Zolota V, Zozaya-Alvarez E (2012) S2: Pathology update. Quality assurance guidelines for pathology. In: Perry N, Broeders M, de Wolf C, Törnberg S, Holland R, von Karsa L (eds) European guidelines for quality assurance in breast cancer screening and diagnosis. Fourth edition/ Supplements. European Commission, Office for Official Publications of the European Union, Luxembourg, pp 73–120

Ahn HS, Jang M, Kim SM, Yun BL, Kim SW, Kang EY, Park SY (2016) Diagnosis of columnar cell lesions and atypical ductal hyperplasia by ultrasound-guided core biopsy: findings associated with underestimation of breast carcinoma. Ultrasound Med Biol 42(7):1457–1463

Badan GM, Roveda Junior D, Piato S, Fleury Ede F, Campos MS, Pecci CA, Ferreira FA, D’Avila C (2016) Diagnostic underestimation of atypical ductal hyperplasia and ductal carcinoma in situ at percutaneous core needle and vacuum-assisted biopsies of the breast in a Brazilian reference institution. Radiol Bras 49(1):6–11

Co M, Kwong A, Shek T (2018) Factors affecting the under-diagnosis of atypical ductal hyperplasia diagnosed by core needle biopsies: a 10-year retrospective study and review of the literature. Int J Surg (Lond Engl) 49:27–31

Collins LC, Aroner SA, Connolly JL, Colditz GA, Schnitt SJ, Tamimi RM (2016) Breast cancer risk by extent and type of atypical hyperplasia: an update from the Nurses’ Health Studies. Cancer 122(4):515–520

Degnim AC, Dupont WD, Radisky DC, Vierkant RA, Frank RD, Frost MH, Winham SJ, Sanders ME, Smith JR, Page DL et al (2016) Extent of atypical hyperplasia stratifies breast cancer risk in 2 independent cohorts of women. Cancer 122(19):2971–2978

Donaldson AR, McCarthy C, Goraya S, Pederson HJ, Sturgis CD, Grobmyer SR, Calhoun BC (2018) Breast cancer risk associated with atypical hyperplasia and lobular carcinoma in situ initially diagnosed on core-needle biopsy. Cancer 124(3):459–465

Khoury T, Li Z, Sanati S, Desouki MM, Chen X, Wang D, Liu S, Karabakhtsian R, Kumar P, Reig B (2016) The risk of upgrade for atypical ductal hyperplasia detected on magnetic resonance imaging-guided biopsy: a study of 100 cases from four academic institutions. Histopathology 68(5):713–721

Latronico A, Nicosia L, Faggian A, Abbate F, Penco S, Bozzini A, Cannataci C, Mazzarol G, Cassano E (2018) Atypical ductal hyperplasia: our experience in the management and long term clinical follow-up in 71 patients. Breast 37:1–5

Menen RS, Ganesan N, Bevers T, Ying J, Coyne R, Lane D, Albarracin C, Bedrosian I (2017) Long-Term safety of observation in selected women following core biopsy diagnosis of atypical ductal hyperplasia. Ann Surg Oncol 24(1):70–76

Menes TS, Kerlikowske K, Lange J, Jaffer S, Rosenberg R, Miglioretti DL (2017) Subsequent breast cancer risk following diagnosis of atypical ductal hyperplasia on needle biopsy. JAMA Oncol 3(1):36–41

Mesurolle B, Perez JC, Azzumea F, Lemercier E, Xie X, Aldis A, Omeroglu A, Meterissian S (2014) Atypical ductal hyperplasia diagnosed at sonographically guided core needle biopsy: frequency, final surgical outcome, and factors associated with underestimation. AJR Am J Roentgenol 202(6):1389–1394

Pena A, Shah SS, Fazzio RT, Hoskin TL, Brahmbhatt RD, Hieken TJ, Jakub JW, Boughey JC, Visscher DW, Degnim AC (2017) Multivariate model to identify women at low risk of cancer upgrade after a core needle biopsy diagnosis of atypical ductal hyperplasia. Breast Cancer Res Treat 164(2):295–304

Yu CC, Ueng SH, Cheung YC, Shen SC, Kuo WL, Tsai HP, Lo YF, Chen SC (2015) Predictors of underestimation of malignancy after image-guided core needle biopsy diagnosis of flat epithelial atypia or atypical ductal hyperplasia. Breast J 21(3):224–232

Acott AA, Mancino AT (2016) Flat epithelial atypia on core needle biopsy, must we surgically excise? Am J Surg 212(6):1211–1213

Berry JS, Trappey AF, Vreeland TJ, Pattyn AR, Clifton GT, Berry EA, Schneble EJ, Kirkpatrick AD, Saenger JS, Peoples GE (2016) Analysis of clinical and pathologic factors of pure, flat epithelial atypia on core needle biopsy to aid in the decision of excision or observation. J Cancer 7(1):1–6

Chan PMY, Chotai N, Lai ES, Sin PY, Chen J, Lu SQ, Goh MH, Chong BK, Ho BCS, Tan EY (2018) Majority of flat epithelial atypia diagnosed on biopsy do not require surgical excision. Breast 37:13–17

Dialani V, Venkataraman S, Frieling G, Schnitt SJ, Mehta TS (2014) Does isolated flat epithelial atypia on vacuum-assisted breast core biopsy require surgical excision? Breast J 20(6):606–614

Lamb LR, Bahl M, Gadd MA, Lehman CD: Flat epithelial atypia: upgrade rates and risk-stratification approach to support informed decision making. J Am Coll Surg 2017

McCroskey Z, Sneige N, Herman CR, Miller RA, Venta LA, Ro JY, Schwartz MR, Ayala AG: Flat epithelial atypia in directional vacuum-assisted biopsy of breast microcalcifications: surgical excision may not be necessary. Mod Pathol 2018

Rudin AV, Hoskin TL, Fahy A, Farrell AM, Nassar A, Ghosh K, Degnim AC (2017) Flat epithelial atypia on core biopsy and upgrade to cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg Oncol 24(12):3549–3558

Samples LS, Rendi MH, Frederick PD, Allison KH, Nelson HD, Morgan TR, Weaver DL, Elmore JG (2017) Surgical implications and variability in the use of the flat epithelial atypia diagnosis on breast biopsy specimens. Breast 34:34–43

Schiaffino S, Gristina L, Villa A, Tosto S, Monetti F, Carli F, Calabrese M (2018) Flat epithelial atypia: conservative management of patients without residual microcalcifications post-vacuum-assisted breast biopsy. Br J Radiol 91(1081):20170484

Yamashita Y, Ichihara S, Moritani S, Yoon HS, Yamaguchi M (2016) Does flat epithelial atypia have rounder nuclei than columnar cell change/hyperplasia? A morphometric approach to columnar cell lesions of the breast. Virchows Arch 468(6):663–673

Dabbs DJ, Schnitt SJ, Geyer FC, Weigelt B, Baehner FL, Decker T, Eusebi V, Fox SB, Ichihara S, Lakhani SR et al (2013) Lobular neoplasia of the breast revisited with emphasis on the role of E-cadherin immunohistochemistry. Am J Surg Pathol 37(7):e1–e11

Fasola CE, Chen JJ, Jensen KC, Allison KH, Horst KC (2018) Characteristics and clinical outcomes of pleomorphic lobular carcinoma in situ of the breast. Breast J 24(1):66–69

Flanagan MR, Rendi MH, Calhoun KE, Anderson BO, Javid SH (2015) Pleomorphic lobular carcinoma in situ: radiologic-pathologic features and clinical management. Ann Surg Oncol 22(13):4263–4269

Sullivan ME, Khan SA, Sullu Y, Schiller C, Susnik B (2010) Lobular carcinoma in situ variants in breast cores: potential for misdiagnosis, upgrade rates at surgical excision, and practical implications. Arch Pathol Lab Med 134(7):1024–1028

AGO (2018) Läsionen unsicheres Potential. https://www.ago-online.de/fileadmin/downloads/leitlinien/mamma/2018-03/AGO_2018_PDF_Deutsch/2018D%2006_Laesionen%20unsicheres%20Potential.pdf

Haagensen CD, Lane N, Lattes R, Bodian C (1978) Lobular neoplasia (so-called lobular carcinoma in situ) of the breast. Cancer 42(2):737–769

Fisher ER, Land SR, Fisher B, Mamounas E, Gilarski L, Wolmark N (2004) Pathologic findings from the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project: twelve-year observations concerning lobular carcinoma in situ. Cancer 100(2):238–244

King TA, Pilewskie M, Muhsen S, Patil S, Mautner SK, Park A, Oskar S, Guerini-Rocco E, Boafo C, Gooch JC et al (2015) Lobular carcinoma in situ: a 29-year longitudinal experience evaluating clinicopathologic features and breast cancer risk. J Clin Oncol 33(33):3945–3952

Ansquer Y, Delaney S, Santulli P, Salomon L, Carbonne B, Salmon R (2010) Risk of invasive breast cancer after lobular intra-epithelial neoplasia: review of the literature. Eur J Surg Oncol 36(7):604–609

Chuba PJ, Hamre MR, Yap J, Severson RK, Lucas D, Shamsa F, Aref A (2005) Bilateral risk for subsequent breast cancer after lobular carcinoma-in-situ: analysis of surveillance, epidemiology, and end results data. J Clin Oncol 23(24):5534–5541

Blair SL, Emerson DK, Kulkarni S, Hwang ES, Malcarne V, Ollila DW (2013) Breast surgeon’s survey: no consensus for surgical treatment of pleomorphic lobular carcinoma in situ. Breast J 19(1):116–118

Bodian CA, Perzin KH, Lattes R (1996) Lobular neoplasia. Long term risk of breast cancer and relation to other factors. Cancer 78(5):1024–1034

Cavallaro U, Dejana E (2011) Adhesion molecule signalling: not always a sticky business. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 12(3):189–197

Chen YY, Hwang ES, Roy R, DeVries S, Anderson J, Wa C, Fitzgibbons PL, Jacobs TW, MacGrogan G, Peterse H et al (2009) Genetic and phenotypic characteristics of pleomorphic lobular carcinoma in situ of the breast. Am J Surg Pathol 33(11):1683–1694

Susnik B, Day D, Abeln E, Bowman T, Krueger J, Swenson KK, Tsai ML, Bretzke ML, Lillemoe TJ (2016) Surgical outcomes of lobular neoplasia diagnosed in core biopsy: prospective study of 316 cases. Clin Breast Cancer 16(6):507–513

Muller KE, Roberts E, Zhao L, Jorns JM (2018) Isolated atypical lobular hyperplasia diagnosed on breast biopsy: low upgrade rate on subsequent excision with long-term follow-up. Arch Pathol Lab Med 142(3):391–395

Szynglarewicz B, Kasprzak P, Halon A, Matkowski R (2017) Lobular carcinoma in situ of the breast - correlation between minimally invasive biopsy and final pathology. Archiv Med Sci 13(3):617–623

Calhoun BC, Collie AM, Lott-Limbach AA, Udoji EN, Sieck LR, Booth CN, Downs-Kelly E (2016) Lobular neoplasia diagnosed on breast Core biopsy: frequency of carcinoma on excision and implications for management. Ann Diagn Pathol 25:20–25

Fives C, O’Neill CJ, Murphy R, Corrigan MA, O’Sullivan MJ, Feeley L, Bennett MW, O’Connell F, Browne TJ (2016) When pathological and radiological correlation is achieved, excision of fibroadenoma with lobular neoplasia on core biopsy is not warranted. Breast 30:125–129

Mao K, Yang Y, Wu W, Liang S, Deng H, Liu J (2017) Risk of second breast cancers after lobular carcinoma in situ according to hormone receptor status. PLoS ONE 12(5):e0176417

Maxwell AJ, Clements K, Dodwell DJ, Evans AJ, Francis A, Hussain M, Morris J, Pinder SE, Sawyer EJ, Thomas J et al (2016) The radiological features, diagnosis and management of screen-detected lobular neoplasia of the breast: Findings from the Sloane Project. Breast 27:109–115

Nakhlis F, Gilmore L, Gelman R, Bedrosian I, Ludwig K, Hwang ES, Willey S, Hudis C, Iglehart JD, Lawler E et al (2016) Incidence of adjacent synchronous invasive carcinoma and/or ductal carcinoma In-situ in patients with lobular neoplasia on core biopsy: results from a prospective multi-institutional registry (TBCRC 020). Ann Surg Oncol 23(3):722–728

Schmidt H, Arditi B, Wooster M, Weltz C, Margolies L, Bleiweiss I, Port E, Jaffer S: Observation versus excision of lobular neoplasia on core needle biopsy of the breast. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2018

Sen LQ, Berg WA, Hooley RJ, Carter GJ, Desouki MM, Sumkin JH (2016) Core breast biopsies showing lobular carcinoma in situ should be excised and surveillance is reasonable for atypical lobular hyperplasia. AJR Am J Roentgenol 207(5):1132–1145

Xie ZM, Sun J, Hu ZY, Wu YP, Liu P, Tang J, Xiao XS, Wei WD, Wang X, Xie XM et al (2017) Survival outcomes of patients with lobular carcinoma in situ who underwent bilateral mastectomy or partial mastectomy. Eur J Cancer 82:6–15

Ahn SK, Han W, Moon HG, Kim MK, Noh DY, Jung BW, Kim SW, Ko E (2018) Management of benign papilloma without atypia diagnosed at ultrasound-guided core needle biopsy: scoring system for predicting malignancy. Eur J Surg Oncol 44(1):53–58

Armes JE, Galbraith C, Gray J, Taylor K (2017) The outcome of papillary lesions of the breast diagnosed by standard core needle biopsy within a BreastScreen Australia service. Pathology 49(3):267–270

Bianchi S, Bendinelli B, Saladino V, Vezzosi V, Brancato B, Nori J, Palli D (2015) Non-malignant breast papillary lesions - b3 diagnosed on ultrasound-guided 14-gauge needle core biopsy: analysis of 114 cases from a single institution and review of the literature. Pathol Oncol Res 21(3):535–546

Khan S, Diaz A, Archer KJ, Lehman RR, Mullins T, Cardenosa G, Bear HD: Papillary lesions of the breast: To excise or observe? Breast J 2017

Kim SY, Kim EK, Lee HS, Kim MJ, Yoon JH, Koo JS, Moon HJ (2016) Asymptomatic benign papilloma without atypia diagnosed at ultrasonography-guided 14-gauge core needle biopsy: which subgroup can be managed by observation? Ann Surg Oncol 23(6):1860–1866

Ko D, Kang E, Park SY, Kim SM, Jang M, Yun B, Chae S, Jang Y, Kim HJ, Kim SW et al (2017) The management strategy of benign solitary intraductal papilloma on breast core biopsy. Clin Breast Cancer 17(5):367–372

Moon SM, Jung HK, Ko KH, Kim Y, Lee KS (2016) Management of clinically and mammographically occult benign papillary lesions diagnosed at ultrasound-guided 14-gauge breast core needle biopsy. J Ultrasound Med 35(11):2325–2332

Niinikoski L, Hukkinen K, Leidenius MHK, Stahls A, Meretoja TJ (2018) Breast Lesion Excision System in the diagnosis and treatment of intraductal papillomas: a feasibility study. Eur J Surg Oncol 44(1):59–66

Pareja F, Corben AD, Brennan SB, Murray MP, Bowser ZL, Jakate K, Sebastiano C, Morrow M, Morris EA, Brogi E (2016) Breast intraductal papillomas without atypia in radiologic-pathologic concordant core-needle biopsies: rate of upgrade to carcinoma at excision. Cancer 122(18):2819–2827

Seely JM, Verma R, Kielar A, Smyth KR, Hack K, Taljaard M, Gravel D, Ellison E (2017) Benign papillomas of the breast diagnosed on large-gauge vacuum biopsy compared with 14 gauge core needle biopsy-do they require surgical excision? Breast J 23(2):146–153

Tatarian T, Sokas C, Rufail M, Lazar M, Malhotra S, Palazzo JP, Hsu E, Tsangaris T, Berger AC (2016) Intraductal papilloma with benign pathology on breast core biopsy: to excise or not? Ann Surg Oncol 23(8):2501–2507

Tran HT, Mursleen A, Mirpour S, Ghanem O, Farha MJ (2017) Papillary breast lesions: association with malignancy and upgrade rates on surgical excision. Am Surg 83(11):1294–1297

Wyss P, Varga Z, Rossle M, Rageth CJ (2014) Papillary lesions of the breast: outcomes of 156 patients managed without excisional biopsy. Breast J 20(4):394–401

Yamaguchi R, Tanaka M, Tse GM, Yamaguchi M, Terasaki H, Hirai Y, Nonaka Y, Morita M, Yokoyama T, Kanomata N et al (2015) Management of breast papillary lesions diagnosed in ultrasound-guided vacuum-assisted and core needle biopsies. Histopathology 66(4):565–576

Yang Y, Fan Z, Liu Y, He Y, Ouyang T (2018) Is surgical excision necessary in breast papillomas 10 mm or smaller at core biopsy. Oncol Res Treat 41(1–2):29–34

Co M, Chen C, Tsang JY, Tse G, Kwong A (2017) Mammary phyllodes tumour: a 15-year multicentre clinical review. J Clin Pathol 71:493–497

Ouyang Q, Li S, Tan C, Zeng Y, Zhu L, Song E, Chen K, Su F (2016) Benign phyllodes tumor of the breast diagnosed after ultrasound-guided vacuum-assisted biopsy: surgical excision or wait-and-watch? Ann Surg Oncol 23(4):1129–1134

Sevinc AI, Aksoy SO, Guray Durak M, Balci P (2018) Is the extent of surgical resection important in patient outcome in benign and borderline phyllodes tumors of the breast? Turk J Med Sci 48(1):28–33

Shaaban M, Barthelmes L (2017) Benign phyllodes tumours of the breast: (over) treatment of margins: a literature review. Eur J Surg Oncol 43(7):1186–1190

Youk JH, Kim H, Kim EK, Son EJ, Kim MJ, Kim JA (2015) Phyllodes tumor diagnosed after ultrasound-guided vacuum-assisted excision: should it be followed by surgical excision? Ultrasound Med Biol 41(3):741–747

Zhou ZR, Wang CC, Sun XJ, Yang ZZ, Yu XL, Guo XM (2016) Diagnostic performance of core needle biopsy in identifying breast phyllodes tumors. J Thorac Dis 8(11):3139–3151

Hamperl H (1975) Radial scars (scarring) and obliterating mastopathy (author’s transl). Virchows Archiv A 369(1):55–68

Eusebi V, Grassigli A, Grosso F (1976) [Breast sclero-elastotic focal lesions simulating infiltrating carcinoma]. Pathologica 68(985–986):507–518

Donaldson AR, Sieck L, Booth CN, Calhoun BC (2016) Radial scars diagnosed on breast core biopsy: frequency of atypia and carcinoma on excision and implications for management. Breast 30:201–207

Ferreira AI, Borges S, Sousa A, Ribeiro C, Mesquita A, Martins PC, Peyroteo M, Coimbra N, Leal C, Reis P et al (2017) Radial scar of the breast: is it possible to avoid surgery? Eur J Surg Oncol 43(7):1265–1272

Hou Y, Hooda S, Li Z (2016) Surgical excision outcome after radial scar without atypical proliferative lesion on breast core needle biopsy: a single institutional analysis. Ann Diagn Pathol 21:35–38

Kalife ET, Lourenco AP, Baird GL, Wang Y (2016) Clinical and radiologic follow-up study for biopsy diagnosis of radial scar/radial sclerosing lesion without other atypia. Breast J 22(6):637–644

Kim EM, Hankins A, Cassity J, McDonald D, White B, Rowberry R, Dutton S, Snyder C (2016) Isolated radial scar diagnosis by core-needle biopsy: Is surgical excision necessary? SpringerPlus 5:398

Leong RY, Kohli MK, Zeizafoun N, Liang A, Tartter PI (2016) Radial scar at percutaneous breast biopsy that does not require surgery. J Am Coll Surg 223(5):712–716

Li Z, Ranade A, Zhao C (2016) Pathologic findings of follow-up surgical excision for radial scar on breast core needle biopsy. Hum Pathol 48:76–80

Miller CL, West JA, Bettini AC, Koerner FC, Gudewicz TM, Freer PE, Coopey SB, Gadd MA, Hughes KS, Smith BL et al (2014) Surgical excision of radial scars diagnosed by core biopsy may help predict future risk of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 145(2):331–338

Nassar A, Conners AL, Celik B, Jenkins SM, Smith CY, Hieken TJ (2015) Radial scar/complex sclerosing lesions: a clinicopathologic correlation study from a single institution. Ann Diagn Pathol 19(1):24–28

Park VY, Kim EK, Kim MJ, Yoon JH, Moon HJ (2016) Mammographically occult asymptomatic radial scars/complex sclerosing lesions at ultrasonography-guided core needle biopsy: follow-up can be recommended. Ultrasound Med Biol 42(10):2367–2371

Bahl M, Barzilay R, Yedidia AB, Locascio NJ, Yu L, Lehman CD: High-risk breast lesions: a machine learning model to predict pathologic upgrade and reduce unnecessary surgical excision. Radiology 2017:170549

Shaffer K (2018) Can machine learning be used to generate a model to improve management of high-risk breast lesions? Radiology 286(3):819–821

NHS (2016) NHS Breast Screening Programme. Clinical guidance for breast cancer screening assessment. NHSBSP publication number 49, Fourth edition November 2016

Thill M, Liedtke C, Muller V, Janni W, Schmidt M (2018) AGO recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with advanced and metastatic breast cancer: update 2018. Breast Care (Basel) 13(3):209–215

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all members of the MIBB working group for their reliable good work of entering data for all of their patients who had a VAB. Active breast units entering data in 2017 were as follows: Institut für Radiologie, Kantonsspital Aarau, Aarau (D.Schwegler-Guggemos), Radiologie, Brust-Zentrum Hirslanden Kliniken Aarau Cham Zug, Aarau (W.Santner), Interdisziplinäres Brustzentrum Baden, Kantonsspital Baden, Baden (R.Kubik-Huch), Radiologie St. Claraspital, St. Claraspital Basel, Basel (C.Oursin), Radiologisches Institut, Bethesda-Spital Basel, Basel (P.Trabucco), Frauenklinik Radiologie, Brustzentrum Universitätsspital Basel, Basel (S.Dellas), Radiologie Nordwest, IMAMED, Basel (A.Schmid), Ospedale San Giovanni, Centro di Senologia della Svizzera Italiana, Bellinzona (S.Zehbe), Radiologie, Lindenhofspital Bern, Bern (S.Gasser), Praxis und Senologie Lindenhofspital, Gemeinschaftspraxis Brun del Re/Thomi, Bern (R.Brun del Re), Brustzentrum, Inselspital, Bern (J.Krol), Klinik Engeried, Brustzentrum Bern, Bern (M.Sonnenschein), Radiologie, Hirslanden Brustzentrum Bern Biel, Bern (P.Sager), Radiologie, Spitalzentrum Biel, Biel (U.Tesche), Hauptstrasse 11, Praxisklinik Binningen, Binningen (D.Musfeld), Brust-Zentrum, Spital Bülach, Bülach (M.L.Kaufmann), Radiologie, Clinique des Grangettes, Chênes-Bougeries (K.Kinkel), Frauenklinik Fontana, Brustzentrum Kantonsspital Graubünden, Chur (P.Fehr), Brustzentrum Thurgau/Radiologie, Kantonsspital Frauenfeld, Brustzentrum Radiologie, Frauenfeld (D.Wetter), Brustzentrum Thurgau/Frauenklinik, Kantonsspital Frauenfeld, Frauenfeld (M.Fehr), Radiologie, Hôpital cantonal Fribourg, Fribourg (Q.D.Vo), Service de Radiologie, Hôpital Daler, Fribourg (PDi Blasio), Radiologie, Institut ImageRive, Genève (F.Couson), L’Institut d’Imagerie Médicale, Imagerie médicale Genève, Genève (V.Cerny), Service de Radiologie. Unité de radiologie gynécologique, Hôpitaux Universitaires Genève, Genève (D.Botsikas), Institut d’Imagerie Médicale, Clinique Genolier, Genolier (S.Schlup Pidoux), Radiologie, Kantonales Spital Grabs, Grabs (D.Wruk), Centre d’imagerie sénologique, Imagerie du Flon, Lausanne (D.Lepori), RAD Radiologie Diagnostique et Radiologie Interventionnelle, CHUV, Lausanne (J.-Y.Meuwly), Radiologie, Clinique de la Source, Lausanne (R.-M.Maréchal), Centro di Radiologia e Senologia Luganese, Centro di Radiologia e Senologia Luganese, Lugano (G.Kampmann), Clinica Sant’Anna, Clinica Sant’Anna, Lugano (D.Faedda), Radiologie, EOC Lugano, Lugano (V. A.Vitale), Radiologie, Senologia Ticino, Breast Unit, Lugano (E.Pusterla), Radiologie-Mammadiagnostik, Kantonsspital Luzern, Luzern (C.Kurtz), Gynäkologie, Kantonsspital Luzern, Luzern (S.Bucher), Hirslanden-Klinik St. Anna, Senologie, Hirslanden-Klinik St. Anna, Luzern (R.Goette), Radiologie, Spital Männedorf, Männedorf (C.Stoupis), Brustteam Zürich, Brustteam Zürich, Richterswil (R.Stoffel), Frauenklinik/Brustzentrum SenoSuisse, Kantonsspital Schaffhausen, Schaffhausen (K.Breitling), Spital Limmattal Radiologie, Brustzentrum Zürich-West, Schlieren (S.Potthast), Radiologie, Röntgeninstitut Schwyz AG, Schwyz (A.Mayer), Radiologie, Institut de Radiologie de Sion, Sion (D.Fournier), Gynäkologie und Gebursthilfe, Kantonsspital Solothurn, Solothurn (F.Maurer-Marti), Tumor- und Brustzentrum ZeTuP, St. Gallen, Tumor- und Brustzentrum ZeTuP, St. Gallen, St. Gallen (V.Dupont Lampert), Brustzentrum Kantonsspital St. Gallen, Brustzentrum St. Gallen, St. Gallen (D.Matt), Radiologie im Silberturm, Radiologie im Silberturm, St.Gallen (A.Papathanassiou), Radiologie, Spital STS AG, Thun (I.Honnef), Frauenklinik, GZO Spital Wetzikon, Wetzikon (J.Schneider), Frauenklinik Kantonsspital Winterthur, Brustzentrum Kantonsspital Winterthur/RIL, Winterthur (T.Hess), Radiologie, Radiologie am Graben, Winterthur (P.Scherr), Radiologie, Radiologiezentrum Zug, Zug (M.Livers), Brust-Zentrum Zürich Seefeld, Brust-Zentrum Zürich Seefeld, Zürich (C.Tausch), Brustzentrum, Klinik im Park Hirslanden, Zürich (S.Hosch), Gynäkologie/Radiologie, BrustCentrum Zürich-Bethanien, Zürich (O.Köchli), Klinik für Gynäkologie, Universitätsspital Zürich, Zürich (D.Fink), Frauenklinik Maternité, Stadtspital Triemli, Zürich (S.von Orelli).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest in the context of this publication.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments. Informed consent: Data collected are part of the mandatory national quality assurance database, why no additional informed consent had to be obtained from the patients included in the study.

Informed consent

Data collected are part of the mandatory national quality assurance database, why no additional informed consent had to be obtained from the patients included in the study.

Additional information

The original version of this article was revised due to a retrospective Open Access order.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Rageth, C.J., O’Flynn, E.A.M., Pinker, K. et al. Second International Consensus Conference on lesions of uncertain malignant potential in the breast (B3 lesions). Breast Cancer Res Treat 174, 279–296 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-018-05071-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-018-05071-1