Abstract

Family rejection has negative health consequences for Latinx sexual minority men (LSMM). However, LSMM often reconcile with their families, a phenomenon cross-sectional studies miss. We analyzed longitudinal data from the Healthy Young Men’s Study in Los Angeles. We used individual fixed-effects Poisson regression to model changes over time in the associations among family support, drug use, and depressive symptoms. We found that (1) the initiation of drug use was associated with a 7.2% (Ratio=1.072, 95% CI 1.006 - 1.142, p = 0.03) increase in family support among LSMM who reported high depressive symptoms (depression subscale T-score ≥ 63) in at least one data wave; (2) a 1-unit increase in family support was associated with a 4.7% (RR = ;0.953, 95% CI 0.931 - 0.976, p < 0.001) decrease in the probability of high depressive symptoms; and (3) no significant association between a change in drug use and a change in high depressive symptoms. Over time, LSMM appear to benefit from the health effects of family support associated with Latinx family structures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Latinx familism is associated with positive physical and mental health outcomes [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. Latinx family life is qualitatively distinct from that of non-Hispanic Whites [8]. It differs in at least three dimensions: structural (presence of nuclear and extended kin), behavioral (provision of social support), and attitudinal (prioritizing family loyalty and solidarity among members) [9, 10]. Another feature of Latinx familism is that members often choose healthy behaviors to “do right” by their family [11]. Hence, familial cultural values have been leveraged to reduce drug and alcohol use among Latinx youth [12,13,14]. Among adolescents, familism is associated with fewer depressive symptoms [15, 16], while family conflict is associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms [17].

However, Latinx sexual minority men (LSMM) do not seem to reap all the health benefits of familism. Compared to the parents of White SMM, parents of LSMM tend to have more traditional gender role beliefs that are associated with higher levels of rejection of their son’s sexual orientation [18]. Rejection has negative health consequences: LSMM who reported higher levels of family rejection during adolescence were 5.9 times as likely to report high levels of depressive symptoms and 3.4 times as likely to use psychoactive drugs compared with those who reported no or low levels of family rejection [19]. Some LSMM report using drugs to cope with family rejection and stigma [20, 21]. A study of over 900 LSMM across three cities in the United States found that 80% of them reported having depressed mood [20]. Mental health challenges among Latinx adolescents and adults are associated with drug use [22, 23].

Family rejection is not the whole story for LSMM. After coming out, many LSMM reconcile with their families over time, a phenomenon that cross-sectional studies miss [24, 25]. We know that family dynamics and behaviors also change over time, so we were interested in the temporal trends in the associations between family support and both drug use and depressive symptoms. We focus on drug use and depressive symptoms because people who use drugs and report symptoms of depression are more likely to exhibit social dysfunction and social impairment than people who use drugs but report no symptoms of depression [26, 27]. Hence, LSMM who report both drug use and depressive symptoms may exhibit more social dysfunction, signaling a need for greater familial support than those who use drugs but do not also have a mental health disorder.

Most research has focused on cross-sectional associations between family support or rejection and drug use and mental health. In contrast, we analyzed longitudinal data of young LSMM in Los Angeles to examine changes over time in the associations among family support, drug use, and mental health. For drug use, we focused on stimulants and opioids because these are two classes of drugs that are common to young adults who hold sexual minority identities in Los Angeles and are linked to health threats, including depressive symptoms [28, 29]. We controlled for living situation because living situations structure social relationships, the process of social support, and the self-management behaviors of individuals [30, 31]. We tested three hypotheses:

H1: Over time, increases in drug use lead to an increase in the level of family support.

We tested whether an increase in reported drug use over time led to a concurrent increase in family support among people who reported high depressive symptoms in at least one wave of the study. We restricted the analysis to this group because, in those not prone to depressive symptoms, families may not become aware of their drug use because their use has likely not impacted their ability to function [26, 27]. To confirm this potential difference between the groups, we also separately tested for a relationship between increase in drug use and increase in family support among the group of participants who never reported depressive symptoms in the study, although we did not expect to see a significant association.

H2: Increases in the level of family support over time lead to concurrent decreases in the probability of high depressive symptoms (defined as depression subscale T-score ≥ 63).

We examined whether increases in family support over time in those who reported depressive symptoms in at least one wave led to a concurrent decrease in depressive symptoms.

H3: Over time, increases in reported drug use lead to a decrease in the probability of high depressive symptoms (defined as depression subscale T-score ≥ 63).

If an increase in drug use over time leads to an increase in family support, which in turn leads to a decrease in depressive symptoms, we should also see a relationship between an increase in drug use and decrease in depressive symptoms. Because this could play out over a longer period than 6 months (the time between successive study visits), we tested for both a concurrent relationship between increase in drug use and decrease in depressive symptoms and a lagged relationship (i.e., decrease in depressive symptoms one study visit after the increase in drug use) in separate models.

Methods

Overview

This study analyzed data from the Healthy Young Men’s Study (HYM), a longitudinal research project focused on preventing HIV and improving the health and wellness of Black, Latinx, and multiracial young men who have sex with men in Los Angeles. Data are collected in the following domains: insurance status and access to care; drug use including alcohol, marijuana, and other illicit drugs; use and access to HIV/STI testing and treatment services; for young men with HIV, their retention in HIV/AIDS care and adherence to anti-retroviral treatment; and use of biomedical prevention interventions, such as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP). (For a full description see Kipke et al. [32].)

Description of Data

Original Data Source

A total of 448 subjects were recruited into the HYM study. Young men were eligible to participate if they were assigned male sex at birth; 16 to 24 years old; self-identified as gay, bisexual, or uncertain about their sexual orientation; reported having had sex with another man within the last 12 months; a resident of Los Angeles or a surrounding county and did not anticipate moving for at least six months; and self-identified as African American/Black or Hispanic/Latino or multi-racial/ethnic. The young men were recruited using both venue-based and social media recruitment strategies [33].

Analytic Sample

We restricted our sample to the 291 participants who self-identified as male and Hispanic/Latino, regardless of race. We analyzed six waves of data collected between 2016 and 2020.

Measures

Outcomes

Perceived Social Support from Family

(α = 0.90) [34]. We used four items from this study instrument (e.g., I can talk about my problems with my family). Responses were given on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1-“Very Strongly Disagree” to 7-“Very Strongly Agree.” We calculated the total family support score as the sum of the 4 items. Higher scores reflect greater levels of perceived social support from family members.

Depressive Symptoms

[35]. We used the Brief Symptom Inventory 18 to measure psychological distress over the past seven days. It consists of 18 items on a 5-point (0–4) Likert scale and includes subscales for somatization, depression, and anxiety. We focused on the depression subscale (α = 0.84), which consists of 6 items. A high score indicates greater distress. The maximum raw score for this subscale is 24; scores were converted to a T-score based on community norms. We dichotomized the variable, < 63 or ≥ 63; a T-score of 63 indicates a higher level of depressive symptoms.

Predictors

Drug Use.

We focused on stimulants and opioid use. We defined this variable as self-reported use of stimulants (cocaine, crack, methamphetamine) or opioids (heroin, fentanyl) in the last 6 months. We created a dichotomous variable (yes/no) for reported use of any of these drugs due to the heterogeneity of drugs reported and the small numbers in cells for specific drugs used.

Living situation.

This was a categorical variable to indicate where participants lived during each wave of the study: with family, with friends/partner, own place, or no regular place.

Analysis Plan

We used individual fixed-effects (IFE) Poisson regression to model changes over time in the outcomes as a function of changes over the same time in the predictors listed above. We chose IFE regression to maximize our ability to infer causality because IFE regression eliminates confounding by all time-invariant characteristics of the participant, regardless of whether they are measured (such as ethnic origin) or not measurable (e.g., inherited tendencies). IFE models can be thought of as ordinary linear regression with separate flags for each individual participant included as covariates. To control for time-varying characteristics, we included living situation in a given wave (with family, own place, with friends/partner, no regular place) as a covariate in the IFE models.

We used the fixest package in R to conduct the analyses; we used the standard 5% threshold for Type I error (alpha) to determine statistical significance.

Results

Participant Characteristics

The mean age of participants at baseline was 22.1 (SD = 2.0) and across waves was 23.3 (SD = 2.0). Seventy-four (25%) reported living with their families across all waves; 141 (49%) were employed across all waves; and 58 (20%) were in school across all waves. Only 13 (5%) participants reported depressive symptoms across all waves (depression subscale T-score ≥ 63). Nearly half the cohort, 140 (48%), reported high depressive symptoms at least once, while 151 (52%) participants did not report any depressive symptoms at any wave (Table I). The mean level of family support at baseline was 15.4 (SD = 5.7) on a 4–28 point scale.

We also found a small difference in the pattern of drug use between those who never reported high depressive symptoms in any wave and those who reported high depressive symptoms in at least one wave. This finding held both at baseline and across waves (Table II).

Multivariable, Individual Fixed Effects Regression Analysis

H1: Over time, increases in drug use lead to an increase in the level of family support.

Initiation of drug use was associated with a 7.2% (Ratio = 1.072, 95% CI 1.006–1.142, p = 0.03) increase in the level of family support only among people who reported high depressive symptoms (depression subscale T-score ≥ 63) in at least one wave; no association (Ratio = 1.014, 95% CI 0.964–1.067, p = 0.57) was found among those who never reported high depressive symptoms; and living situation had no association with family support in either group of participants (Table III).

H2: Increases in the level of family support over time lead to concurrent decreases in the probability of high depressive symptoms.

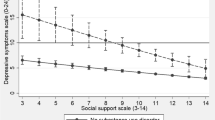

A 1-unit increase in family support was associated with a 4.7% (RR = 0.953, 95% CI 0.931–0.976, p < 0.001) decrease in the probability of high depressive symptoms (depression subscale T-score ≥ 63) (Table IV).

H3: Over time, increases in reported drug use lead to a decrease in the probability of high depressive symptoms (defined as depression subscale T-score ≥ 63).

Contrary to our hypothesis that a within-person change in drug use was predictive of a within-person change in the probability of high depressive symptoms occurring either concurrently or delayed, we did not find any significant association between a change in drug use and a change in high depressive symptoms (Table V).

Discussion

Family support can play a positive role in the health of LSMM. In Hypothesis 1 we tested whether uptake of drug use over time led to an increase in the level of family support. We found that over time, initiating drug use is associated with a 7.2% (Ratio = 1.072, 95% CI 1.006–1.142, p = 0.03) increase in the participants’ perceived level of family support only for those who reported high depressive symptoms in at least one wave. This finding suggests that families play an important role in addressing drug use among LSMM and aligns with studies that show that familial cultural values are important to address drug use [12,13,14]. Conversely, stopping drug use is associated with a decrease in perceived family support. This may be because participants do not require a greater level of support once they stop their drug use. Because family support increased only among participants who reported high depressive symptoms in at least one wave, we infer that families may need more education to identify problematic drug use in the absence of depressive symptoms to be able to support these individuals as well.

In Hypothesis 2 we tested whether, over time, increases in the level of family support lead to a decrease in the probability of high depressive symptoms (defined as depression subscale T-score ≥ 63). Findings support this hypothesis, with increases in family support related to a 4.7% (RR = 0.953, 95% CI 0.931–0.976, p < 0.001) decrease in the probability of high depressive symptoms among participants who reported such symptoms in at least one wave. This is consistent with studies showing that familism is associated with decreased depressive symptoms [15, 16]. For LSMM facing mental health challenges, family support makes a difference. Juxtaposing this finding with studies demonstrating the negative links between family rejection and mental health outcomes [17, 19, 20] challenges us to develop nuanced understandings of how family ties affect the mental health of LSMM beyond initial experiences of rejection of their sexual orientation.

Because reported drug use initiation was associated with an increase in the level of family support, and an increase in the level of family support was associated with a decrease in the probability of high depressive symptoms, we tested Hypothesis 3, that over time, increases in reported drug use lead to a decrease in the probability of high depressive symptoms (defined as depression subscale T-score ≥ 63). We found no associations. Although families are protective against drug use and depressive symptoms, their support does not guarantee that their members will not develop a substance use disorder or a mental health disorder. The long-term effect of drug use on family support and mental health among LSMM requires further study.

The majority of participants (74.6%) did not live with their families of origin at all waves. Yet there was no statistically significant difference between living at home or having other living arrangements in terms of family support and depressive symptoms outcomes. Further research is needed to determine whether the living situation of LSMM moderates the association between levels of family support and drug use initiation and the association between family support and high depressive symptoms. Exploring living situation as a moderator of family support could complement studies showing that Latinx people report greater familial support than other racial/ethnic groups and are more likely to live with extended family [6, 36].

This study points to potential future studies on LSMM, drug use, and family support. Our results imply that we need longitudinal research on how the family members of LSMM can be engaged in drug use interventions. First, some LSMM with a history of drug use have reported that strained family ties were reestablished over time [24, 25]. Second, some LSMM with a history of drug use have reported that they prioritize family support for behavior change despite experiences of family rejection [19, 20, 24, 37]. Hence, a nuanced view of family support over time may help us overcome the dearth of family-based drug use interventions specifically for LSMM. To our knowledge, most Latinx family-based interventions for drug use have overlooked SMM, even though connectedness with family protects against drug use in this and other populations of young Latinx people [38,39,40,41].

We speculate that more interventions to promote acceptance of sexual orientation among family members are needed. Some LSMM may never experience acceptance from their families or it may take decades [42], while others do experience varying levels of acceptance [24]. We need to understand the processes by which some Latinx families come to accept LSMM’s sexual orientation. This may be accomplished by interviewing LSMM about their familial interactions after their families learned of their sexual orientation. At the same time, we need to ensure we develop a culturally and generationally appropriate understanding of what acceptance of sexual orientation looks like within Latinx families [24]. This may be done by interviewing family members about their own journey of acceptance of their LSMM relative.

Limitations

We do not know whether the participants were out to their families before or during the study, or not at all. This could affect family support. We also do not know whether and to what extent LSMM in our sample experienced family rejection and resolution related to their sexual orientation. However, unlike cross-sectional studies, our study found that over time, increases in drug use are associated with increases in family support, which in turn are associated with a decrease in depressive symptoms at potentially critical points in the lives of young LSMM. The association between increases in drug use and increases in family support suggests that the effect of families on LSMM’s mental health and their relevance for addressing drug use is dynamic and important [24].

Conclusion

Despite potential experiences of family rejection, LSMM over time appear to benefit from the health effects of family support associated with Latinx family structures. Our findings suggest that families can play a significant role in helping to bring about positive health outcomes for LSMM. Conducting longitudinal analyses of family support of LSMM demonstrates that family rejection does not represent the full experience of LSMM family life. This is missing in our conversations about LSMM. Ultimately, gaining a deeper and more subtle understanding of the role of family support over time in the lives of LSMM may help us address their drug use and mental health challenges.

Availability of Data and Materials

The data analyzed during the current study are available from Michele Kipke, PhD, principal investigator of the Healthy Young Men Study, on reasonable request.

Availability of Data and Materials

Not applicable.

References

Ayon C, Marsiglia FF, Bermudez-Parsai M. Latino family Mental Health: exploring the role of discrimination and familismo. J Community Psychol. 2010;38(6):742–56.

Harker K. Immigrant generation, assimilation, and adolescent psychological well-being. Soc Forces. 2001;79:969–89.

Gil AG, Wagner EF, Vega WA. Acculturation, familism and alcohol use among latino adolescent males: longitudinal relations. J Community Psychol. 2000;28:443–58.

Shavitt S, Johnson CY, Jiang TP, Holbrook D, Stavrakantonaki A. Culture Moderates the relation between perceived stress, Social Support, and Mental and Physical Health. J Cross-Cult Psychol. 2016;47(7):956–80.

Mulvaney-Day NE, Alegria M, Sribney W. Social cohesion, social support, and health among Latinos in the United States. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64(2):477–95.

Almeida J, et al. Is blood thicker than water? Social support, depression and the modifying role of ethnicity/nativity status. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011;65(1):51–6.

Rodriguez N, et al. Exploring the complexities of familism and acculturation: central constructs for people of mexican origin. Am J Community Psychol. 2007;39(1–2):61–77.

Vega W. The study of latino families, Understanding latino families: Scholarship, policy, and practice, Z. R, Editor. 1995, Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA. 3–17.

A, V. and D. SM, Familism and social capital in the academic achievement of mexican origin and anglo adolescents. Soc Sci Q, 1994. 75: p. 18–36.

Editors MF. 2006, National Research Council (US) Panel on Hispanics in the United States: Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US).

Davila YR, Reifsnider E, Pecina I. Familismo: influence on hispanic health behaviors. Appl Nurs Res. 2011;24(4):e67–72.

Ma M, et al. Cultural Assets and Substance Use among hispanic adolescents. Health Educ Behav. 2017;44(2):326–31.

Lardier DT Jr, et al. Preventing substance use among hispanic urban youth: valuing the role of family, social support networks, school importance, and community engagement. J Child Adolesc Subst Abuse. 2018;27(5–6):251–63.

Telzer EH, Gonzales N, Fuligni AJ. Family obligation values and family assistance behaviors: protective and risk factors for mexican–american adolescents’ substance use. J Youth Adolesc. 2014;43(2):270–83.

Cupito AM, Stein GL, Gonzalez LM. Familial cultural values, depressive symptoms, school belonging and grades in latino adolescents: does gender matter? J Child Fam stud. 2015;24(6):1638–49.

Stein GL, et al. The protective role of Familism in the lives of latino adolescents. J Fam Issues. 2015;36(10):1255–73.

Lorenzo-Blanco EI, et al. Acculturation, enculturation, and symptoms of depression in hispanic youth: the roles of gender, hispanic cultural values, and family functioning. J Youth Adolesc. 2012;41(10):1350–65.

Richter BEJ. Sociocultural variables associated with parental rejection in parents of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth: the impact on LGB youth adjustment. University of Miami; 2015.

Ryan C, et al. Family rejection as a predictor of negative health outcomes in white and latino lesbian, gay, and bisexual young adults. Pediatrics. 2009;123(1):346–52.

Diaz RM, et al. The impact of homophobia, poverty, and racism on the mental health of gay and bisexual latino men: findings from 3 US cities. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(6):927–32.

Dolezal C, et al. Substance use and sexual risk behavior: understanding their association among four ethnic groups of latino men who have sex with men. J Subst Abuse. 2000;11(4):323–36.

McCance-Katz E. National Survey on Drugs Use and Health: Hispanics, latino or spanish origin or descent. Volume 14. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2020.

Gonzalez-Guarda RM, Florom-Smith AL, Thomas T. A syndemic model of substance abuse, intimate partner violence, HIV infection, and mental health among Hispanics. Public Health Nurs. 2011;28(4):366–78.

del Pino HE, et al. Negotiating emotional support: Sober Gay Latinos and their families. J Gay Lesbian Social Serv. 2014;26:1–22.

Del Pino HE, et al. Stigma and Family Relationships of Middle-Aged Gay Men in Recovery. J Gay Lesbian Soc Serv. 2016;28(1):1–19.

Donohue B, Acierno R, Kogan E. Relationship of depression with measures of social functioning in adult drug abusers. Addict Behav. 1996;21(2):211–6.

Erfan S, et al. Effect of comorbid depression on substance use disorders. Subst Abus. 2010;31(3):162–9.

Gorbach PM, et al. Methamphetamine injection among young men who have sex with men: risk for human immunodeficiency virus transmission in a Los Angeles cohort. J Infect Dis. 2020;222(Supplement5):S471–6.

Strathdee SA, et al. Collateral damage: a narrative review on epidemics of substance use disorders and their relationships to sexually transmitted infections in the United States. Sex Transm Dis. 2021;48(7):466.

House JS, Umberson D, Landis KR. Structures and processes of social support. Ann Rev Sociol. 1988;14(1):293–318.

Irani E, et al. The contribution of living arrangements, social support, and self-efficacy to self-management behaviors among individuals with heart failure: a path analysis. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2019;34(4):319.

Kipke MD, et al. Club drug use in los angeles among young men who have sex with men. Subst Use Misuse. 2007;42(11):1723–43.

Kipke MD, et al. The healthy young men’s cohort: health, stress, and Risk Profile of black and latino young men who have sex with men (YMSM). J Urb Health. 2020;97(5):653–67.

Procidano ME, Heller K. Measures of perceived social support from friends and from family: three validation studies. Am J Community Psychol. 1983;11(1):1–24.

Derogatis LR, Melisaratos N. The brief symptom inventory: an introductory report. Psychol Med. 1983;13(3):595–605.

Almeida J, et al. Ethnicity and nativity status as determinants of perceived social support: testing the concept of familism. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68(10):1852–8.

Diaz RM. Latino gay men and HIV: culture, sexuality, and risk behavior. New York: Routledge; 1998. xv, 192 p.

Castro FG, Stein JA, Bentler PM. Ethnic pride, traditional family values, and acculturation in early cigarette and alcohol use among latino adolescents. J Prim Prev. 2009;30(3–4):265–92.

Unger JB, et al. Peer influences and access to cigarettes as correlates of adolescent smoking: a cross-cultural comparison of Wuhan, China, and California. Prev Med. 2002;34(4):476–84.

Marsiglia FF, et al. Cohesion and conflict: family influences on adolescent alcohol use in immigrant latino families. J Ethn Subst Abuse. 2009;8(4):400–12.

Holloway IW, et al. Psychological distress, health protection, and sexual practices among young men who have sex with men: using social action theory to guide HIV prevention efforts. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(9):e0184482.

Mitrani VB, et al. The impact of parental reaction to sexual orientation on depressive symptoms and sexual risk behavior among hispanic men who have sex with men. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2017;31(4):352–8.

Acknowledgements

Homero E. del Pino received support from NIH/NIMHD K01MD015002, R25MD007610, and NIH/NIA P30AG021684. Homero E. del Pino and Arun Karlamangla were supported by NIH/NIAID P30AI152501. Homero E. del Pino and Nina T. Harawa were supported by NIH/NCRR/NCATS UL1TR001881. Homero E. del Pino and Katrina Schrode were supported by NIH/NIMHD U54MD007598 and S21MD000103. Nina T. Harawa and Katrina Schrode were also supported by the California HIV/AIDS Research Program (CHRP) OS17-LA-003. Steven J. Shoptaw and Nina T. Harawa received support from NIH/NIMH P30MH58107. Steven J. Shoptaw also received support from NIH/NIDA U01DA036267. The Healthy Young Men Study was funded by NIH/NIDA U01DA036926. We are thankful to Dr. Pamina Gorbach for support through NIH/NIDA U24DA044554 Collaborating Consortium of Cohorts Producing NIDA Opportunities (C3PNO). The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Funding

Open access funding provided by SCELC, Statewide California Electronic Library Consortium. The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study conceptualization and design were performed by Homero E. del Pino, Nina T. Harawa, Arun Karlamangla, and Steven Shoptaw. Formal analyses were performed by Katrina Schrode. Writing – review and editing, performed by all authors, including reading and approving the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of Interest

Not applicable.

Ethics Approval

This study falls under a Category 4 exemption from IRB review because we are analyzing a deidentified dataset.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

del Pino, H.E., Harawa, N.T., Shoptaw, S.J. et al. Drug Use, Family Support, and Depressive Symptoms Among Latinx Sexual Minority Men: A Longitudinal Analysis. AIDS Behav 27, 3844–3851 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-023-04098-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-023-04098-w