Abstract

Building on 42 semi-structured interviews with directors and stakeholders of food charities based in Greater Manchester (UK), alongside online data and Factiva references trends, I argue that the charitable food provision (CFP) sector can be effectively conceptualized as a strategic action field (SAF). To do so, I first focus on the shared rules, understandings and practices characterising the organizations that belong to the field and on the broader field environment that imposes constraints and provides opportunities to the field actors. Subsequently, I examine the characteristics of five particularly relevant charities to describe the social positions and position-takings of the incumbent, the challengers and the group I refer to as sideliners of the field. Hence, I briefly touch upon the Covid-19 outbreak as an exogenous shock to discuss the effect of the campaign carried out by a ‘socially skilled actor’ - football player Marcus Rashford. I conclude by suggesting future research directions to enhance the application of SAF theory as a tool for investigating food support organizing within and across countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The growth and institutionalisation of food charities across the global north has spurred academic debate at least since the 90s. Already in 1994, Poppendieck (1994) summarised the strengths and weaknesses of the charitable food provision sector in the US in the article Dilemmas of Emergency Food: A guide for the perplexed. Almost 30 years later, the paper is still current in listing of the tensions and ambiguities affecting the provision of food support in high-income countries. In Europe, where food assistance has long been part of civil society, an increasing body of country-specific research has highlighted that the growth and institutionalisation of food support provision has occurred in conjunction with the retrenchment of social security programmes, the 2000s economic crises and the austerity measures taken after the Great Recession (Lambie-Mumford and Silvasti 2020). Particularly in the UK, the rise of food support has been most visible and discussed, possibly because several organisations have advocated for and provided evidence of the high levels of food insecurity throughout the country. The Covid-19 pandemic further confirmed the centrality of food charities in addressing financial precarity and food poverty, as increases in the number of food parcels distributed were reported from several organisations (Power et al. 2020; Boons et al. 2020; Oncini 2021; Hirth et al. 2022).

The growing importance of food support providers as a safety net for the poorest ones has been paralleled by a plethora of scholarly studies dissecting and analyzing various facets of food support provision and food poverty, providing fine-grained case studies, saddening ethnographies (Garthwaite 2016), and detailed descriptions of how various providers work (Williams et al. 2016). Literature to date has been fundamental to increasing our understanding of charitable food provision and its ambiguous relation with food loss and surplus. However, we still lack a coherent theoretical framework that can account for food charities’ relationships of conflict and interdependence, their shared understanding, boundaries, social positioning, and power relationships. This paper aims to advance the literature on charitable food provision (CFP) by illustrating that the sector can be usefully framed as a field, and particularly as a strategic action field (SAF) (Fligstein and McAdam 2012). Building on a case study of Greater Manchester CFP field conducted in 2020, the paper shows how SAF meso-level theorization provides a valuable lens to understand CFP dynamics both in times of stasis and crisis, and discusses possibilities to extend research of food support in a comparative perspective. In this context, the term ‘meso’ refers to the fact that the focus of our attention is the explanation of social action in an empirically defined arena (the CFP field), where actors take each other into account in their framings and in their actions (Kluttz and Fligstein 2016).

The paper is organised as follows. I first provide an overview of the literature distinguishing between three main research streams that have characterised the study of CFP. I then outline how field theories have been applied in the non-profit sector (Barman 2016) and explain why I rely on SAF theory to describe the CFP field in Greater Manchester. After presenting the region of Greater Manchester as a typical case study (Gerring 2007) and the data collection strategy, I explore the CFP field around four main propositions capturing the central building blocks of SAF theory: first, I highlight the shared rules, understandings and practices that characterise the organisations that belong to the field; second, I focus on the broader field environment and identify distant and proximate fields that impose constraints on and offer opportunities to the actors; third, I illustrate the social positions and interests of some of the most relevant organisations operating in the field; finally, I focus on Covid-19 as an exogenous shock, and provide some evidence on the effect of the campaign carried out by an extremely ‘socially skilled’ actor (the football player Marcus Rashford). In the conclusions, I outline future research developments to extend the investigation of CFP fields across countries using SAF theory as a conceptual tool.

Charitable food provision in high-income countries

The importance acquired by food charities in higher-income countries is hard to understate. The number of non-profit organisations providing parcels or meals has increased virtually everywhere, and so did scholarly publications. While the Covid-19 crisis comprehensibly put in the spotlight the hard and compassionate work of food support providers and spurred reflections on the social and environmental sustainability of our food systems (Sanderson 2020; Hirth et al. 2022), the consolidation of food charities as a permanent – if undesirable – feature of social security in wealthier societies took place much less recently, and found in the aftermath of the financial crisis a fundamental tipping point (Lambie-Mumford and Silvasti 2020). Literature to date dissected the phenomenon of food support to a great extent and can be broadly distinguished into three main streams.

Survey data played a fundamental role in examining the characteristics of food support providers and their users (Loopstra et al. 2019; Oncini 2021; 2022a), to identify diverse food charity profiles (González-Torre and Coque 2016), to map their distribution and accessibility in the territory (Bacon and Baker 2017; Casellas Connors et al. 2022), and also to evaluate their long-term impact on the food security levels of people living in poverty (Tarasuk et al. 2020; Rizvi et al. 2021). In the UK, using data from the Trussell Trust – the largest food bank network – some scholars were able to demonstrate the existence of a causal relationship between cuts in welfare services, reforms of social security payments, benefits sanctioning and the growth of food banks (Loopstra et al. 2015, 2018, 2019). Especially during the Covid-19 crisis, survey data provided an overview of the challenges and the innovations undertaken by the sector to continue operations, as well as documentation of the increasing number of people in need for food support (e.g. Warshawsky 2022; Oncini 2022a).

The bird’s-eye view obtained through survey data has been complemented by enlightening qualitative accounts of the experiences of people forced to rely on food assistance, stressing the feelings of shame, stigma and embarrassment that come with food support, and on the difficulties of transitioning back to buying food (Garthwaite 2016; Purdam et al. 2016; Moraes et al. 2021). Scholars have also examined the organisational life of food banks to reflect on their ambivalent nature: on one side, food banks do not offer solely food support, but a ‘space of care’ characterised by moral support, empathetic listening, advice and hospitality that can turn into a space to coordinate food justice campaigns and raise awareness of the structural nature of (food) poverty (Williams et al. 2016; Swords 2019). On another (darker) side, the organisation of food banks – through the use of intrusive assessment procedures, vouchers and referral systems – is increasingly indistinguishable from the welfare system (May et al. 2019, 2020), albeit one that provides food, rather than cash, transfers. Inspired by Foucauldian concepts, some authors have highlighted how these procedures seek to act over the conduct, capacities, and capabilities of lives through conditionality and triage, demarcating between lives that are provisioned and those for whom the protections and provisions of foodbanks are suspended (Strong 2019). Systems of food support are often imbued with subtle and explicit forms of coercion, as highlighted in the use of pastoral power to obtain detailed knowledge of subjects’ poverty histories and biographies, and in the disciplinary acts entailed in the monitoring of their conducts and limiting their entitlements (Möller, 2021; Power and Small 2022).

Finally, a third stream paid attention to the ambiguous relationship between food poverty and food loss. As awareness and moral outrage over food waste increased, food surplus became one of the key sources of charitable food distribution. Hence, the institutionalisation of food support has been further cemented by the idea that recovering food loss and reducing food poverty could represent a win-win (Caplan 2017; Lohnes and Wilson 2018; Arcuri 2019; Tikka 2019), although arguably such an approach neither solves inefficiencies in the production and distribution chain, nor addresses poverty. The ambiguity is further amplified by the emergence of an anti-hunger industrial complex (Fisher 2017), with corporations benefiting from food surplus distribution and food donations in terms of brand image and public relations. At the same time, some have argued that re-evaluating food loss can actually become the means for food charities to replace the personal stigma attached to food aid with an ethics based on care toward the environment and the other participants (Edwards 2021).

Despite the aforementioned themes recur across countries and allowed the scholarly community to engage in a productive international and interdisciplinary debate, literature to date still lacks a meso-level theoretical framework that could let us consider how different charities relate to each other within the same arena, and potentially to compare different CFP systems across regions and countries. Among meso-level theories, field theory has been extremely successful in providing a set of conceptual tools to understand how sectors within the market, the state, and the civil spheres operate.

Understanding meso-level social orders using field theory

The term field theory identifies a conceptual framework in sociology seeking to explain social action in a particular social arena (Kluttz and Fligstein 2016; Hilgers and Mangez 2015). In studying the third sector, its application has been particularly fruitful, as the theory proposed an interpretation of the sector’s structure and internal dynamics that could make sense of the origin, diffusion and institutionalisation of several non-profit organisations, social enterprises and social movements (Spicer et al. 2019; Barman 2016; Chen 2018; Lang and Mullins 2020).

According to Barman (2016: 445), the sociological contributions to the study of the non-profit sector de facto overlapped with the introduction of field theory, which can depart from both methodological individualism – excessively concerned with explaining voluntaristic action by actors’ motivations, beliefs or ascribed characteristics – and the view of the third sector as an autonomous space in society resulting from inefficiencies in the public sector and failures of the market to take care of the public good. Instead, field theory posits a substantial resemblance between field dynamics regardless of the subject field’s nature (market, public, non-profit) (Barman 2016); in fact, it is particularly well suited to investigate mutual imbrication and common modus operandi across spheres (Spicer et al. 2019; Lang and Mullins 2020).

Although field theories are often seen in dialogue with each other, and central concepts recur across approaches (Barman 2016; Kluttz and Fligstein 2016), each version emphasises different aspects of how a field works, which in turn can trigger alternative, rather than complementary, descriptions and explanations (Kluttz and Fligstein 2016). For example, Bourdeusian approaches (Bourdieu and Wacquant 1992; Hilgers and Mangez 2015) stress how struggle and competition over material and symbolic resources characterise all fields, and therefore also the ones constituted around charitable donations, altruistic behaviour or public interest (e.g. Ostrower 1995; Greenspan 2014). New institutionalism, on the other hand, has mostly been concerned with how and why organisations within a field tend to homogenise, and suggested that business practices are imitated because they confer legitimacy in the eyes of the stakeholders and not necessarily because they are efficient (Di Maggio and Powell 1983). More recently, SAF theory (Fligstein and McAdam 2012) attempted a synthesis of these approaches. The authors say a SAF is

a constructed mesolevel social order in which actors (who can be individual or collective) are attuned to and interact with one another on the basis of shared (which is not to say consensual) understandings about the purposes of the field, relationships to others in the field (including who has power and why), and the rules governing legitimate action in the field (Fligstein and McAdam 2012: 9).

Hence, in line with Bourdieu’s approach, actors in a SAF are unequally positioned, vie for advantage and compete to define the rules of the game depending on the quantity and composition of capital they control - social, economic, cultural and eventually symbolic (Bourdieu, 1986). Analytically, this means that in a SAF we should always be able to identify incumbents – ‘actors who wield disproportionate influence within a field and whose interests and views tend to be heavily reflected in the dominant organizations’ of the SAF, and challengers ‘who wield little influence over its operation’ and ‘while they recognise the dominant logic of incumbent actors … can usually articulate an alternative vision of the field and their position in it’ (Fligstein and McAdam 2012: 13). At the same time, in line with new institutionalism, SAF agrees that already existing fields contain forces pushing organisations towards conformity, stability and eventually reproduction. Externally, various forms of certification by state actors can ensure compliance with field rules. Internally, the authors introduce the concept of internal governance units, namely non-state organisations that facilitate the functioning and reproduction of the field – and therefore of its power relationships – by ‘overseeing compliance with the rules’ (Fligstein and McAdam 2012: 13).

While fully recognising its debts, however, SAF theory contains several innovative features that are particularly helpful for describing the functioning of food charities in Greater Manchester – and in the UK at large. First, next to competition (and coercion), Fligstein and McAdam stress that cooperation is a fundamental force at play in each field, as actors act strategically both when they jockey for legitimacy and when they aim to secure the cooperation of others. This is possible because all actors are socially skilled, namely ‘possess a highly developed cognitive capacity for reading people and environments, framing lines of actions, and mobilizing people in the service of broader conceptions of the world and of themselves’ (Fligstein and McAdam 2012: 17). This capacity is more pronounced in some individuals, and depending on their role in the field – and on its stability – they could help reproduce the status quo (incumbents) or mobilise other people to reorganise the field (challengers). As we will see, especially in a field oriented towards a collective end – such as feeding the most disadvantaged – hierarchy, competition and cooperation are at work simultaneously, and continuously structure the field and its internal struggles for legitimacy.

A second distinctive feature concerns the importance given to the broader environment in which a field operates. On one side, we are invited to think that fields work like Russian dolls: ‘open up an SAF and it contains a number of other SAFs’ (Fligstein and McAdam 2012: 3). On the other, SAF theory accords analytical importance to the broader environment surrounding fields and provides some binary distinctions that help make sense of the extended network in which they operate. Other fields can be distant or proximate depending on the ties they have with the field being studied; dependent or interdependent if subjected to different influences; and distinguishing state from non-state fields identifies whether the field possesses the authority ‘to intervene in, set rules for, and generally pronounce on the legitimacy and viability of most nonstate fields’ (Fligstein and McAdam 2012: 19). This second characteristic of the theory will greatly help to single out the field relationships within the CFP field, and between it and its environment, as well as to highlight potential application of SAF in proximate fields of interest. In this context, I will show the critical role of food surplus distribution as a distinct, yet proximate, field, capable of affecting the dynamics of the CFP field to a great extent.

Finally, SAF theory is particularly attentive to processes of field emergence and change, and identifies three principal external sources of field destabilisation: invasion by outside groups – when a powerful outside actor enters the field and alters the existing equilibrium; specific changes in proximate fields or broader ones in the field environment; and large-scale exogenous shocks creating a sense of generalised crisis. I will illustrate how the outbreak of Covid-19 has possibly marked the beginning of a period of contention in the field, with powerful new actors entering the arena. In fact, the Manchester United footballer Marcus Rashford – a representative socially skilled outside actor – was able to partly modify the power relationships at work by becoming an ambassador for FareShare, the biggest food surplus distributor in the UK.

Study context, data and methods

Greater Manchester is a city-region in Northwest England comprising ten local authority districts and a population of 2.8 million. Despite successfully transitioning from an industrial- to a modern knowledge-based economy, the region is marked by significant economic disparities (Folkman et al. 2016). The unemployment rates are higher, and workers earn less than the national average. Additionally, one in four children lives in relative poverty (before housing costs), and 15% of households experience fuel poverty (GMPA 2022). Given the high levels of food insecurity and diffusion of food charities in Greater Manchester (GMPA 2020, 2021), the region could be considered a typical case ‘capable [of] provid[ing] insight into a broader phenomenon’ (Gerring 2007: 91). Focusing on Greater Manchester enabled the consideration of relationships between different actors, including small food charities with one distribution centre and large organisations covering several regions or the entire country, without losing sight of the roles of local and national authorities alike. Moreover, using Greater Manchester as a starting point for the investigation bridges the conceptual scale of SAF theory with the geographical scale of the region. In line with Jonas (2006, 402, emphasis mine), the region ‘can be seen to operate both as a between space and a mesolevel concept, which is amenable to thinking about a spatial combination of flows, connections, processes, structures, networks, sites, places, settings, agencies and institutions’.

During the initial months of the Covid-19 pandemic, I started gathering data on the food charities active in the metropolitan area of Greater Manchester (UK) with a variety of techniques.Footnote 1 Using the map of food support providers accessible on the website of the Greater Manchester Poverty Action (GMPA) charity, I conducted a small quantitative survey to understand how food charities were adapting to the new safety measures (Oncini 2021; 2022a). The survey was followed by a series of semi-structured interviews with 30 directors and 12 additional stakeholders recruited using personal contacts and snowball sampling. The interview sample includes Trussell Trust (the largest UK food bank network) and independent food banks (often members of the Independent Food Aid Network, IFAN), pantries, warm meal providers and a few others operating with a mixture of methods. Among stakeholders, I interviewed directors of charities that distribute funding, three area managers or coordinators from Trussell Trust, IFAN and FareShare, experts in food surplus redistribution and members of advocacy groups. Following SAF theory, the questions aimed to obtain information about the rules and understandings of the field, its power structure and symbolic boundaries, the embeddedness and broader interlinkages, and the effect of Covid-19 as an exogenous shock (Oncini 2022b). All the interviews were recorded, anonymised, then transcribed verbatim, and participants were thanked via a charity donation.

Interviews were complemented by several other data sources that could help obtain a more detailed depiction of the field. First, I examined the websites, blogposts and yearly reports of several food charities and stakeholders to understand how they presented themselves and their approach to food poverty; second, I obtained income and turnover data of relevant organisations using the Charity register database; third, I mapped all the food charities active on Twitter and examined their social network (Oncini and Ciordia 2023); fourth, I used the Factiva database – a news aggregator with more than 30,000 sources (such as newspapers, journals, etc.) – to outline the emergence and structuring of the CFP field. In particular, I focused on the number of times different food charity types (food bank(s), soup kitchen(s) and pantry(ies) with related synonyms)Footnote 2 appeared in UK-based news sources, trade publications, transcripts and press releases between 2010 and 2020. Fifth, I used newspaper articles on food poverty, food support, and the UK government measures to counter poverty to contextualise all the other data and to understand how the most powerful field actors were responding to the Covid-19 crisis. Finally, all the data were enriched by gathering fieldnotes at the online meetings of a GM-based umbrella organisation connecting food support initiatives throughout the Covid-19 crisis. The analysis proceeded iteratively while the interviews were taking place, in a continuous and productive feedback loop. Table A1 in the supplementary materials illustrates how the different types of data responded to a specific objective, how they were used in order to inform SAF theoretical blocks, and furnishes some empirical examples.

Charitable food provision as a strategic action field

Shared rules, understandings and practices

The lack of a consistent and agreed terminology surrounding food poverty and food charities has prompted several taxonomic attempts based on types of food provision (e.g. Parsons et al. 2021). Such analytic endeavour can help single out subtle differences between providers but does not inform us on the positions different organisations take in the social space. Here, I rely on the straightforward classification used by GMPA (Greater Manchester Poverty Action) in their mapping of the food support organisations active in Greater Manchester. I think this is the most helpful distinction because among its primary targets are users in search of support. The map distinguishes between food banks, pantries/food clubs and meal providers. Food banks are the best-known providers: people can receive a parcel containing food to take home, prepare and eat. The second includes activities that provide access to groceries, usually every week, for payment of a small subscription. Finally, warm meal providers distribute cooked meals or operate free-access canteens (soup kitchens, soup vans, holiday hunger programmes, breakfast clubs) (Oncini 2022b). Later I will look in more detail at how the different social positions of some leading actors structure the field and underpin their framing of food poverty. Before doing that, however, we need to focus on the shared rules, understandings and practices that make the field relatively autonomous.

As commonplace as it could be, the first element, crucial to comprehending why food charities are embedded in a field, is the role that food plays across all organisations. Despite organising around different types of service and scope, food support lies at the core of all the activities. Whether given for free as a meal or a parcel, or in exchange for a token fee, food is the capital around which the whole field turns. As a matter of fact, all food charities – not just some – played a central role in the provision of emergency food during the Covid-19 crisis (Oncini 2021; Hirth et al. 2022). For all organisations, food is both the material means through which help takes shape, and the social hook around which orbit a whole series of complementary forms of aid, such as empathetic listening, financial advice, addiction treatment and cooking courses. These forms of support, as important as they are, are central for many other anti-poverty organisations that do not provide groceries or meals. Moreover, despite the extremely heterogeneous offer within each type of provision, the channels through which food can be obtained are the same, namely food surplus and/or food donations. Only when these two do not suffice do charities purchase additional groceries, using funding and monetary donations.

At the same time, the field is constructed on a set of shared understandings, rules and practices that push it towards conformism and stability. On a general level, all the interviewees shared a view of what is going on in the field. This common feeling builds on four points generally taken for granted by all food charities’ directors:

-

1.

Cognizance that food poverty in the UK has increased because of the austerity measures taken after the Great Recession and the reform of the social security system that saw the introduction of the Universal Credit;Footnote 3

-

2.

The admission that food charities are just a ‘sticking plaster’ that do not fix the problem of poverty;

-

3.

Awareness that charities working within the field cooperate towards the same goal (i.e. relieving from hunger and possibly ending food poverty) but at times compete for the same resources (funding, food and monetary donations);

-

4.

Identification of the Trussell Trust as the actor that possesses most power and of food banks as the most common type of provider, though not necessarily always the most appropriate type.

In addition, the field rests on two sets of rules that together define legal, meaningful and legitimate courses of action. These rules push the field towards conformity and stability, as they permit uncertainty to be reduced via coercive and mimetic isomorphism (Di Maggio and Powell 1983). On one side, the legal framework forces new food charities entering the field to comply with existing regulations; on the other side, newcomers tend to shape their proposal by selecting among the models at their disposal. The first set of rules refers to the bureaucratic logic the organisations are subjected to qua charities and qua food providers. These primarily include the requirements of charity law (principally, the Charities Act, 2011) that delimit their purpose, duties and obligations; and the food safety requirements, as outlined by the Food Standards Agency (FSA) (among other regulations, the EU General Food Law, The Food Safety and Hygiene (England) Regulations 2013 and The General Food Regulations 2004). A second set of rules refers to the possible ways charities can obtain food (i.e. via donations or surplus) and distribute food, namely as food banks, as pantries, as meal providers. Although a few charities run mixed models and others complement food aid with additional activities (e.g. cookery schools), channels of provision and types of distribution define the field of possibilities that new actors entering the arena can undertake. These are testified by the many online sources explaining ‘how to open’ or ‘how to start’ one of the three types of charitable food provider, often offered in the websites of the organisations themselves – especially those working with a network or affiliate-based model. Finally, each type of provider has internal logics and courses of action it regards as legitimate: for instance, many food banks set a limit to the number of consecutive times users can access a food parcel and often keep a record of users’ access; pantries set a limit to the number of users that can subscribe to the service while aiming to develop a long-lasting relationship with them; conversely, warm meal providers often follow the unwritten rule of offering a meal to everyone without asking for background information (see also Power and Small 2022).

The broader field environment

A second crucial element defining the CFP field is the complex web of distant and proximate fields that impose constraints on and provide opportunities to the actors in the CFP field. Table 1 below illustrates the most important external fields by cross-referring the state/non-state dichotomy to the dependent/interdependent one. First, as partially seen above, the field is largely influenced by a group of distant state agencies and bodies that can lay down bureaucratic and legal requirements and take decisions that affect food charities’ operations. The Charity Commission, with its quasi-judicial function, acts as a registrar and regulator, and deals with monitoring and investigations (UK Government 2020a). The FSA, as seen above, polices the food safety requirements; the Department of the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA), by actively promoting food surplus redistribution, can affect the quantity of food available for CFP. For instance, in the immediate aftermath of the first lockdown, food surplus redistribution organisations across England received £3.25 million to redistribute surplus stock to charities (UK Government 2020b); on the other hand, the decision to end the fund that helped farmers and producers cover the costs of storing and transporting unsold food could reduce the amount of food available to charities (DEFRA 2021).

Finally, HM Treasury and the Department of Work and Pensions, by establishing the government’s public finance policy and administering social security benefits, have the power to influence the field both directly and indirectly. On one side, they can regulate the flow of resources towards charities. On the other, they can indirectly influence the level of food requests charities are going to face by the decisions they take in administering or reforming welfare. A case in point is the roll-out of Universal Credit in 2012, which has been causally associated with increasing the number of food parcels the Trussell Trust needs to distribute (Reeves and Loopstra 2020). Alternately, one might think of the debate surrounding the £20-a-week uplift in Universal Credit introduced during the Covid-19 crisis and then removed once the crisis was ‘over’, despite forecasts that this will pile further pressure on food charities (e.g. Cameron et al. 2021; Patrick et al. 2021).

Unlike national authorities, proximate state fields are in a relation of mutual dependence with the CFP field. In Greater Manchester, these proximate fields mainly amount to the Greater Manchester Combined Authority (GMCA) and its ten councils’ departments dedicated to social care and support. In this sense, the nearer the political field draws to actual deployment of poverty relief measures, the more it becomes imbricated with the CFP field. Clearly, charitable food providers depend on resources: funding distributed by the GMCA and by each council. Yet councils are aware that current welfare measures often are not enough for low-income families to make ends meet and consequently signpost people in need to the local charities of the area – via street-level bureaucrats, hotlines and/or on their websites. During the Covid-19 crisis, this interdependency became a de facto alliance, as the rising number of users requesting food aid and the necessity of maintaining physical distancing measures required a concerted effort to face the emergency. Cross-fertilisation became immediately evident: in April 2020, the GMCA opened a platform that gathered data on food charities and residents in need so as to match and connect them, while Manchester council copied charities’ organisational structure by opening a ‘public’ temporary food bank in partnership with both voluntary and private organisations to delivery emergency parcels (Manchester City Council 2020) – a patent example of mimetic isomorphism.

Among the many non-state fields sharing ties with the CFP field, three are crucial as they are capable to affect charitable food providers’ economic capital, the stock of food and their symbolic capital respectively. First, as well as funding provided by central and local governments, all organisations access resources through grants set up by hundreds of other charities and private organisations (trusts, private companies, etc.) and sometimes through donations by corporate actors. The resources obtained through these grants are fundamental for supporting CFP activities, as they can be used to purchase equipment to store food and cook meals, to directly buy additional foodstuffs and, in the few larger organisations, to sustain staff and running costs. Concurrently, the field is affected by the food surplus distribution sector, as over time this has become more and more relevant both as a source of food and as an agenda setter. In fact, although most food charities are capable of obtaining part of the surplus directly from local retailers, manufacturers or producers, several professional surplus distributors now surrounding the sector make decisions that can greatly affect the CFP field’s dynamics. In the food surplus field, FareShare is the biggest distributor working in the UK (the incumbent of that field), and its decisions can greatly affect perceptions of legitimacy within the CFP field.

Finally, academic research into food poverty constitutes the third non-state field of interest. Scholars’ intellectual capital – prestige ‘measured through the recognition accorded by the scientific field’ (Bourdieu 1988: 79) – confers on (some of) them the authority to shape the discourse on and the social perception of the CFP field by informing the debate with case studies, position papers, quantitative evidence, ethnographic pieces, blogs and newspaper articles. However, the process of generating this knowledge is neither detached nor disengaged from the internal dynamics of the field, since many academics actively collaborate with food charities by offering their expertise to analyse data, write reports and help the charities’ causes – in a sense, by converting their own intellectual capital into symbolic capital for the organisations.

A structured field: incumbents, challengers and sideliners

Like all fields, the CFP arena is characterised by a structured space of positions – determined by the volume and nature of the types of capital at the actors’ disposal – and by position-takings – stances through which actors seek to maintain and increase their influence and legitimacy in the field (Oncini 2022b). Food charities with greater economic capital can usually count on larger organisations working in entire regions or across the UK, employing several paid staff members, adopting clearly defined hierarchies and organigrams and having outside partners and sponsorships. Economic capital can be therefore converted into cultural capital, as higher financial means give access to professional grant writers, managers and communicators. Concurrently, social capital is constituted by the number of volunteers and donors a charity can count on and the formal and informal ties that can be established with the broader field environment (see Table 1). These forms of capital interact with and reinforce each other and eventually contribute, either directly or indirectly, to the food capital of the charity – the stock of foodstuffs and drinks that can be converted into meals or parcels – and to its symbolic capital – namely the ‘collectively recognized credit’ (Bourdieu 1972: 121) (reputation, legitimacy and importance) attributed to the organisation.

In Greater Manchester there are more than 200 food charities (GMPA 2021). These organisations vary to a great extent in reach and in how their capitals are composed, as they range from small independent parishes setting up a food bank, through independent pantries with dozens of users per week, to far-reaching organisations working in multiple locations and across several councils. Although all the food charities in Greater Manchester are part of its CFP field, this section will focus on a few more prominent organisations, so I can identify the incumbent, some crucial challengers and what I have named the sideliner of the field.

The Trussell Trust network counts more than 1,300 food bank centres all over the UK (more than 60 of which are in Greater Manchester). With its 20 years of activity, 121 paid staff members, more than 40,000 volunteers, 2.5 million parcels distributed between March and April 2021 and a 2020 income of more than £21.3 million, the Trust can rightly be considered as the incumbent of the field, and possibly the organisation that made the field emerge (Table A1). In some respects, the initial objective of the charity – ‘every town should have a food bank’ – has almost been met (Lambie-Mumford 2013). The Trussell Trust model mainly relies on the food that private individuals and companies directly donate to the local centres thanks to arrangements put in place by the head charity, and to the trust inspired by its brand image. Although the local centres can eventually rely on surplus through direct contacts and via surplus distributors, tackling food loss is not part of the charity’s mission, which in fact only refers to food as ‘donated by the public at a range of places’ (Trussell Trust 2021).

The charity was the first to operate with a large-scale affiliate-based model, and since the 2008/9 recession, has continually increased the number of affiliated food banks operating all over the country, to the extent that the term ‘food bank’ immediately became associated with the network. The visibility acquired over the years has brought several high-profile corporate and funding partners to back up the Trussell Trust and allowed it to become the reference point around which food poverty issues are discussed, and more recently to organise advocacy campaigns and lobbying activities to end hunger and ‘the need [for] food banks’ in the UK (the current mission of the Trussell Trust).

Although the Trussell Trust was the most successful organisation to scale up and coordinate a nationwide response to the increasing levels of food insecurity, it is by no means the only one. In point of fact, many charities already operated food banks without being affiliated to the Trussell Trust network. Some of them simply wanted to maintain independence and a looser formal structure; others did not want to apply limits to the number of consecutive parcels that users could request, or criticised the corporate partners that backed the Trussell Trust; others again simply existed before the Trussell Trust and were already equipped to manage a food bank on their own; finally, ethnic-specific food banks have appeared to respond to refugees’ and minorities’ need for culturally appropriate food that could not be provided by the Trussell Trust (e.g. Ukeff or the African food bank project based in Oldham). The hidden world of unaffiliated food banks was eventually brought to light by IFAN, which in 2016 surveyed non-Trussell Trust food banks in the UK and began to speak on behalf of the many providers ‘without national representation’. This small charity network now counts more than 500 members UK-wide (32 in Greater Manchester). However, as Table A2 shows, it has operated without paid staff and with an income which is thousands of times smaller than that of the Trussell Trust;Footnote 4 in addition, it only accepts donations over £500 if the donor (i) does not actively increase inequality, (ii) offers real living wages, (iii) does not hold investments in tobacco, arms, oil, pharmaceuticals or alcohol, and (iv) is not looking to use IFAN as a way to improve its reputation – an implicit departure from Trussell Trust reliance on corporate funders, often accused of using charities’ work to improve their brand reputation. In the past, IFAN has challenged the Trussell Trust modus operandi and presented itself as the heterodox alternative whose focus was not to feed the poor, but to fight poverty tout court (Bartholomew 2020). Against the idea that ‘every town should have a food bank’, IFAN immediately aimed to end the need for food aid once and for all and eventually influenced the Trussell Trust to adopt a similar aim. Similarly, it harshly criticised Trussell Trust alliances with corporate members: in 2018, it referred to a £20 million partnership with the British supermarket Asda as ‘disappointing given the company’s own record on low pay’ (IFAN 2018), which in turn is associated with food insecurity.

While IFAN was challenging the Trussell Trust on its own ground, other food charities proposed a different model of food provision. In 2017 a Guardian journalist asked ‘Are pantry schemes the new food banks?’, discussing the rise of this alternative model of support (Butler 2017). As shown below (Fig. 1), pantries are still far from replacing food banks in the public discourse. Nevertheless, they actively challenge the incumbent model by strategically placing themselves as heterodox to all food banks. In fact, pantry schemes (also called food clubs) opposed the food bank model altogether, claiming that the system based on referrals, vouchers and free parcels does not offer a long-term solution to the problem of food poverty, and is responsible for prompting feelings of shame and embarrassment among its users (e.g. Garthwaite 2016). Against this backdrop, pantries claim to offer a more dignified experience based on choice, building community and environmental sustainability. The fact that members usually pay a small weekly fee to access the pantry’s food offer is seen as a way to create a supermarket-like experience - especially since products can be freely picked from the shelves. At the same time, pantries aim to create small communities, as the great majority of their members tend to use these services for longer periods to ride out financial precarity in the longer term. Hence, while food banks are depicted as temporary solutions for the emergency – despite being often used as long-term solutions as well – pantries are thought of as open-ended. Finally, since these schemes mostly rely on food surplus, much of the focus is also on the environmental benefits of saving food from waste.

In Greater Manchester, as elsewhere in the UK, pantries have tended to be independent from other providers, and from one another. In recent years, however, a handful of charities started to scale up their model to increase its reach. One salient example is perhaps Your Local Pantry: the project was launched in 2016 by Foundations Stockport, the charitable arm of a company that manages Stockport Council’s housing stock, and is now run jointly with Church Action Poverty, a large charity with annual income greater than £600,000, dedicated to tackling poverty in the UK. Like the Trussell Trust, Your Local Pantry uses an affiliate-based model and in a short time has opened 35 pantries across the UK (6 in Greater Manchester). It counts on 360 volunteers. Most of its surplus food comes from FareShare, which also appears on its partner list, and it has participated in a promotion video with a FareShare spokesperson for Greater Manchester. The ‘antagonistic’ nature of the organisation is clearly exhibited on its website, which claims that the service wants ‘to go beyond the food bank model creating a sustainable and long-term solution to food poverty’ (Your Local Pantry 2021). Similarly, The bread and butter thing (TBBT) is a charity that totalled £1.81 m in 2020, and that operates several mobile food pantries based on food surplus since 2017. In their latest report, they state that they have helped over 14,000 families ‘stop or reduce their food bank use’ (The bread and butter thing, 2022, p.3). They currently work in the North East and the North West of England, and from 2023 they will expand their operation in three additional regions.

Finally, I use the term ‘sideliner’ to describe food charities like soup kitchens and soup vans, that while not actively engaging in the struggle for legitimacy that characterises the field, are inevitably part of its internal dynamics and are equally affected by the broader field environment. As a matter of fact, during the Covid-19 emergency, warm meal providers helped distributing food next to the other food charities, sometimes switching their mode of provision and distributing parcels as a food bank would do (Oncini 2021). In fact, the provision of cooked meals to people on a low income is the oldest form of organised charitable food distribution, and in the UK it rapidly developed during the 18th and 19th centuries in response to the increasing number of poor and beggars caused by the rise of food prices, wars, stagnant trade and high unemployment (Carstairs 2017). In this sense, warm meal providers have always been here, and it is plausible that in the past they constituted a field by themselves.Footnote 5 With the exception of programmes targeting children’s food poverty during school holidays, today most organisations that distribute cooked meals can be accessed by anyone at any time, as they do not check for vouchers or subscriptions to their services, but provide food to anyone asking for it. At the same time, warm meal providers use the same channels of food provision as other charities (food donations and surplus), rely on volunteers, build relationships with (food) corporate partners and are clearly used by people suffering food poverty.

For instance, like other organisations, FoodCycle states that their vision is to ‘nourish the hungry and lonely in our communities with delicious meals and great conversation, using food which would otherwise go to waste’. The charity was able to scale up its soup kitchen model and now counts 43 projects in the UK (5 of which are in Greater Manchester), a network of 4,600 volunteers and 19 employees, a long list of corporate partners and an annual income of £1.6 million (see Table A1 in the supplemental material). Despite its size, however, the charity cannot be considered a challenger to the food bank model. Like other warm meal providers, it is ‘vulnerable’ to the field’s external shocks (e.g. funding, food availability, number of requests). At the same time, it is ‘strategically’ positioned at the margins of the field, thus remaining distant from the struggle for legitimacy within the field. In a sense, it takes a position by abstaining from position-taking. Its impact report, for example, never mentions other models of provision (as Your Local Pantry does), nor does it discuss the root causes of food insecurity (as IFAN and the Trussell Trust do).Footnote 6

A rough illustration of the emergence and structure of the field can be obtained by looking at the number of times food charities appeared in UK-based news sources, trade publications, transcripts and press releases. The left-hand panel in Fig. 1 presents the number of references retrieved through Factiva divided by type of food charity: food bank(s), soup kitchen(s) and pantry(ies) (with related synonyms).Footnote 7 This provides a concise depiction of the field’s emergence over the last ten years and illustrates the different prominence of the three types of provision. Food banks are the most common, and from 2010 to 2020, moved from 250 to more than 12,000 references; soup kitchens have remained relatively stable, moving up and down between 700 and 1,300 references per year;Footnote 8 finally, pantries have appeared in the public discourse only recently, but displayed an elevenfold increase from 45 to 2010 to 513 in 2020.

In Fig. 1 the right-hand panel presents the number of references to the five food support providers mentioned above and to the largest food surplus distributor (FareShare) over the same period. In this case also we can notice how references to the field grew after 2010, and in particular the capacity of the Trussell Trust to attract news coverage, moving from 55 references in 2010 to 2,351 in 2020. Conversely, the other charities mentioned slightly augmented their media presence but never reached the same penetration.

Covid-19 as an exogenous shock: continuity and change in the CFP field

Although earlier statements may suggest conflict in the CFP field, the actual weekly life of many food charities is built on reciprocal cooperation. At the local level, they often work together and help each other regardless of membership or mode of operation. This is not surprising, as the third sector is often based on community empowerment and collaboration. For instance, it is not uncommon for providers to request food from, and donate it to, one another if shortages or overstocking occur, or to participate in the same events to share experiences and insights on the state and evolution of the sector. Moreover, many food charities are also involved in campaigns such as ‘End Hunger UK’ and ‘End Child Food Poverty’, where coalitions consisting of national charities, frontline organisations, faith groups, academics and individuals advocate to eradicate hunger and poverty in the UK. In a sense, these campaigns represent the social movement arm of the field. Concurrently, they also work politically with local and national government bodies by sitting on committees, sharing evidence and insights from the field, and by running joint pilot schemes. Hence, if discord over the best way to feed the hungry creates fractures and contrapositions within the field, the overriding objective to counter hunger helps draw the actors together (Oncini 2022b). Interestingly, alliances have recently been established even between ‘rival’ head charities: IFAN and the Trussell Trust are currently working together to encourage a ‘cash-first’ approach – switch subsidies from food to cash whenever possible – and since May 2020 have joined a coalition of anti-poverty charities pushing the government to increase social support measures (Trussell Trust 2020).

The food emergency that followed the Covid-19 outbreak further cemented food charity cooperation, as the shocking rise in food requests required coordination among all actors to increase the sector’s reach. Although the destabilisation pushed small providers with low capital to temporarily suspend their activities, the crisis had the paradoxical effect of reinforcing the role of food charities and food surplus distributors, as national authorities heavily relied on both to tackle the crisis (Power et al. 2020; Hirth et al. 2022). This created an ambivalent situation where the two types of organisation overlap. On one side, the Trussell Trust reinforced its incumbency position with stronger funding and an increased media presence, serving as a pillar of the emergency response with its extensive network throughout the UK. On the other side, FareShare expanded its operations during the crisis, distributing both surplus and newly donated food from companies to charities across the UK – interestingly, even including Trussell Trust food banks. This (temporary) field incursion was possible partly because of generous funding dispensed by the government to food surplus organisations (via the Emergency Surplus Food Grant and the Winter Support grant) but most importantly thanks to Marcus Rashford, a popular footballer for Manchester United and the English national team, who had campaigned against food poverty and engaged in philanthropic activities well before Covid-19. In March 2020, Rashford agreed with FareShare CEO Lindsay Boswell to become an ambassador for the organisation, and this immediately impacted the donations inflow. Guardian journalist Adams (2021) reported:

In previous years, the best we might get is £200,000 of donations from the general public,’ Boswell says. ‘Within a week of Marcus’s involvement, we had half a million pounds, from people in 35 different countries. Pre-Marcus, we were delivering 930,000 meals every week. We’re now consistently exceeding 2 million meals – but sadly, we’re still not keeping up with demand.

And as donations surged, so did FareShare’s media presence. The right-hand panel in Fig. 1 shows the references peak: after ten years of relatively modest penetration, in 2020 the charity’s name was cited more than 2,000 times and almost reached the Trussell Trust’s figure.Footnote 9

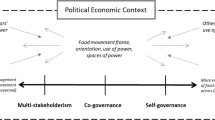

In any SAF, a socially skilled actor is someone capable of inducing cooperation in others. Taking advantage of his celebrity capital (Driessens 2013) in the window of opportunity opened by the Covid-19 crisis, Marcus Rashford successfully provided ‘an interpretation of the situation and frame[d] courses of action that appeal[ed] to existing interests and identities’ (Fligstein 2001: 112). First, by drawing on his experience as a hungry child, he gained the legitimacy to link ‘the personal’ and ‘the structural’ and to create an appealing story that would motivate people to donate. Second, by presenting food poverty from the perspective of children’s hunger, he depicted himself and the problem of food poverty as transversal, apolitical and of general concern. Third, and connected, by indicating which food charity to support and by specifying a fundraising target (£20 million), he set the terms of the discussion and indicated the course of action to follow. Figure 2 summarises the main elements of the CFP field and the impact of Covid-19.

It is hard to evaluate whether Rashford’s effect will have a long-lasting impact on the field. At present, there are signs that the prominence acquired by FareShare during the crisis made more salient the contrast with both IFAN and the Trussell Trust, who are instead advocating ending the need for food charities in the UK by strengthening social support measures. One evident sign of this opposition is the launch of two parallel campaigns, #KeepTheLifeline and #FoodOnPlates. The former, supported by a hundred front-line organisations, urges the government not to cut the £20-a-week Universal Credit supplement, and counts IFAN and the Trussell Trust but not FareShare. Conversely, #FoodOnPlates was launched by FareShare to ask the government not to cut the £5 million annual funding from DEFRA to help farmers send their unsold food to charities, and was not endorsed by IFAN or the Trussell Trust.Footnote 10

Discussion and conclusions

The expansion and consolidation of food charities in the UK has been met with tremendous interest and preoccupation by the scholarly community. Although some authors illustrated how different types of food support can be characterised by contrasting logics (Power and Small 2022), the scientific literature to date has not focused on the meso-level interactions and structured social relations that characterise the sector. In this paper, I build on SAF theory to provide a sociological reading of the CFP sector in a UK context. Using several data sources and SAF theory, I aim to illustrate that considering food charities as part of a field yields considerable advantages. On a general level, the sociological imagination entailed in the use of SAF can be of help to CFP practitioners, decision-makers, and users to understand the connection between the ‘personal troubles’ of individuals’ experiences and the ‘public issues’ of the field, to paraphrase Mills (2000). The theory can in fact provide a better understanding on potential areas of collaboration and competition among food charities within and between fields, and potentially inform decisions on how to allocate resources and coordinate efforts to address poverty and food loss.

Second, looking at the rules, understandings and practices that food charities share lets us understand why we can talk of a CFP field in the first place. Regardless of the differences between models of provision, all food charities distribute food to counter poverty and hunger, and adhere to more or less formalised codes of conduct on how to obtain, manage and distribute food. While doing so, they keep each other into account for either collaborative or competitive purposes.

Third, the emphasis placed on the broader field environment enables us to recognize the actors that have the ability to influence the trajectory of the field - its reproduction and evolution over time. Cross-referring the state/non-state dichotomy with the interdependency/dependency relationship, I have identified various nearby and distant fields that warrant consideration when discussing the CFP field. While these connections have been briefly outlined here, further research can explore the relationship between the broader environment and the Russian doll structure in greater detail to gain a better understanding of fields nestedness and to identify lower- and upper-level fields (Oncini and Ciordia 2023). Given the interdependency of local authorities with food charities, for instance, one could explore the processes through which street-level bureaucrats redirect people in need to the providers, and the role the latter play in the political agenda of councils. Concurrently, as supra-national federations connecting food support and/or food surplus distributors (e.g. the European Food Banks Federation) increase their number of affiliates, it would be crucial to adopt a transnational field perspective (Schmidt-Wellenburg and Bernhard 2020) and investigate cross-border alliances and frictions between incumbents and challengers. In both instances, a promising approach to enhancing our understanding of nestedness involves integrating SAF theory with geography debates on the politics of scale, in order to investigate further the interplay between the social construction of space hierarchies and a relational understanding of social processes (Marston et al. 2005; Jonas 2006).

Fourth, focusing on five, more structured, food charities operating with different models of provision, I single out their social positions and the position-takings in the field. Here, following the theory, I distinguish the incumbent (Trussell Trust) and different challengers both ‘within’ (IFAN) and ‘between’ (Your Local Pantry, TBBT) types of provision. The soup kitchen FoodCycle, and more generally warm meal providers, can be instead called ‘sideliners’. Akin to the other collective actors, sideliners are influenced by the field’s internal dynamics, shared understandings and by the exogenous shocks affecting the field equilibrium; at the same time, they refuse to engage in the struggle for legitimacy, and act as if they had no stakes or interests in the field’s existence. This conceptual addition to SAF theory was necessary to account for the epoché (an attitude that is simultaneously engaged and detached) that we find in interviews and in the organisations’ documents. However, I surmise that sideliners could actually be part of all non-profits fields, as the nature of the sector allows organisations to seem to ‘mind their own business’ and take a neutral stance. Future research should delve deeper into the role of sideliners so as to better characterise their positions and position-takings.

Finally, Covid-19 gave me the opportunity to look at the short-term effects of an unexpected exogenous shock and to consider the polarising impact of an extremely skilled actor in the interstice of two adjacent fields. As shown elsewhere, the emergency response set up by food charities was effective overall, and the field showed considerable adaptability and resilience, and eventually came back to pre-pandemic operations. Now that a new phase of coexistence with the virus seems to be under way, this points to a situation of field reproduction. However, the growing importance of food surplus, especially from an environmental point of view, may leave room for field encroachment processes, a particular type of field emergence where ‘new fields may encroach on existing, overlapping fields, by borrowing their logics to forge a “hybrid” field’ (Spicer et al. 2019, p. 196). Possibly, new lines of enquiry could extend the investigation to the broader environment, and particularly to the food surplus field, to identify the actors and practices that characterise it, and further excavate the web of influence that shapes its close relationship with the CFP field. In addition, the example of food surplus distribution is particularly interesting as it could serve as a focal point for further bridging SAF theory with the sustainability transitions literature (Kungl and Hess 2021). Besides, field theory could be useful to harness for comparative research into other CFP fields in Europe and beyond, possibly building on comparative non-profit sector research (Krause 2018; Anheier et al. 2020). Food charities and food surplus distribution have been increasing everywhere across rich countries, but probably with different trajectories, timing and arrangements. Understanding how charitable food provision – and its relationship with the food surplus distribution field, vary across capitalist regimes could shed further light on how different welfare systems and third sector configurations shape food charity practices, relationships and balance of power, and eventually the lives and survival strategies of the urban poor.

Notes

The project obtained ethical clearance from the University of Manchester Ethics Committee (2020-9377-15273).

As well as ‘pantry’, I searched for: food club(s), pantry scheme(s), community grocer(s), social supermarket(s), community pantry(ies).

The Universal Credit system consolidates various benefits and tax credits into a single payment, designed to decrease welfare dependency and increase financial security for those employed instead of on social security. Additionally, the system includes stricter conditionality requirements and benefit sanctions, and payments are made in arrears to align with common payment practices in the job market.

IFAN currently has two paid staff that have not yet appeared on the Charity Register.

Carstairs (2017) cites an 1887 pamphlet that recorded the existence of over 200 soup kitchens in London serving around 100,000 meals per day.

A similar stance is adopted by Feed My City, a charity that operates a mobile van offering meals around the county. In their website they describe the motivation for their work as follows: ‘we believe that every human being has the right to have a hot meal and this should NOT be dependent on them having money’ (Feed My City 2021).

As well as ‘pantry’, I searched for: food club(s), pantry scheme(s), community grocer(s), social supermarket(s), community pantry(ies).

Interestingly, between 2000 and 2010 references to soup kitchens are always higher than ones to food banks, moving from 241 to 437 (data available upon request). The latter started climbing in 2011 and became the point of reference for discussions about food poverty and food aid following the 2008/9 recession and the subsequent austerity measures (Lambie-Mumford 2013).

Additional analyses show that this increase is attributable to Marcus Rashford’s campaign: between January and March FareShare was mentioned in only 84 articles. Moreover, in 477 articles (22.4% of the total) FareShare’s name appears alongside that of the English footballer.

The #FoodOnPlates campaign was actually criticised by IFAN on several occasions. For instance, the following post appeared on the IFAN Twitter account: ‘It’s appalling that 2 million tonnes of edible food is wasted but the solution is not to direct it to people unable to afford to buy food. We need to stop both hunger and food waste from happening in the first place’ (See https://tinyurl.com/42cbumkb).

References

Adams, T. 2021. Marcus Rashford: the making of a food superhero. The Guardian, 17 January 2021. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/rt5j2n58.

Anheier, H. K., M. Lang, and S. Toepler. 2020. Comparative nonprofit sector research: a critical assessment. In W. W. Powell & P. Bromley (Eds), The nonprofit sector: a research handbook (3rd edition, pp. 648–676). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Arcuri, S. 2019. Food poverty, food waste and the consensus frame on charitable food redistribution in Italy. Agriculture and Human Values 36 (2): 263–275.

Bacon, C. M., and G. A. Baker. 2017. The rise of food banks and the challenge of matching food assistance with potential need: towards a spatially specific, rapid assessment approach. Agriculture and Human Values 34 (4): 899–919.

Barman, E. 2016. Varieties of field theory and the sociology of the non-profit sector. Sociology Compass 10 (6): 442–458.

Bartholomew, J. 2020. The food bank paradox. Prospect Magazine Available at: https://tinyurl.com/tbsvccbr.

Boons, F.A. et al. 2020. Covid-19, changing social practices and the transition to sustainable production and consumption. Version 1.0; (May 2020). Manchester: Sustainable Consumption Institute.

Bourdieu, P. 1972. Esquisse d’une théorie de la pratique, précédé de trois études d’ethnologie kabyle. Geneva: Droz.

Bourdieu, P. 1986. The forms of capital. In Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education, ed. J. G. Richard, 241–258. New York: Greenwood.

Bourdieu, P. 1988. Homo academicus. Cambridge: Polity.

Bourdieu, P., and L. J. Wacquant. 1992. An invitation to reflexive sociology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Butler, P. 2017. Are pantry schemes the new food banks? The Guardian, 22 March 2017. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/yyrb2csc.

Cameron, C., L. Dewar, C. Fitzpatrick, K. Garthwaite, R. Griffiths, K. Hill, … R. Webber. 2021. More, please, for those with less: why we need to go further on the Universal Credit uplift. British Politics and Policy at LSE. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/22e7z7jh.

Caplan, P. 2017. Win-win?: food poverty, food aid and food surplus in the UK today. Anthropology Today 33 (3): 17–22.

Carstairs, P. 2017. Soup and reform: improving the poor and reforming immigrants through soup kitchens 1870–1910. International Journal of Historical Archaeology 21 (4): 901–936.

Casellas Connors, J. P., M. Safayet, N. Rosenheim, and M. Watson. 2022. Assessing changes in food pantry access after extreme events. Agriculture and Human Values, 1–16.

Charities Act 2011, c.25. Available at: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2011/25/contents. Last access 30/06/2023.

Chen, K. K. 2018. Interorganizational advocacy among nonprofit organizations in strategic action fields: exogenous shocks and local responses. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 47 (4S): 97S–118S.

DEFRA. 2021. COVID-19 and the issues of security in food supply: government response to the Committee’s Seventh Report of Session 2019–21. House of Commons. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/4vh3dsxu.

Di Maggio, P. J., and W. W. Powell. 1983. The iron cage revisited: institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review 48 (2): 147–160.

Driessens, O. 2013. Celebrity capital: redefining celebrity using field theory. Theory and society 42 (5): 543–560.

Edwards, F. 2021. Overcoming the social stigma of consuming food waste by dining at the Open table. Agriculture and Human Values 38 (2): 397–409.

Feed My City. 2021. Feeding humanity – supporting people. Available at: https://feedmycity.org/.

Fisher, A. 2017. Big hunger: the unholy alliance between corporate America and anti-hunger groups. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Fligstein, N. 2001. Social skill and the theory of fields. Sociological theory 19 (2): 105–125.

Fligstein, N., and D. McAdam. 2012. A theory of fields. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Folkman, P., J. Froud, and S. Johal, et al. 2016. Manchester Transformed: Why we need a reset of city-region policy. CRESC Public Interest Report, November. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/43tjtzxt. Last access 31 March 2023.

Garthwaite, K. 2016. Hunger pains: life inside foodbank Britain. Bristol: Policy Press.

Gerring, G. 2007. Case study research: principles and practices. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

GMPA. 2020. Greater Manchester poverty monitor. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/fx5y5px8.

GMPA. 2021. Maps of support services. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/5fpuevtr.

GMPA. 2022. Levelling up agenda failing Greater Manchester as shocking scale of poverty revealed. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/5n6cs4cs.

González-Torre, P. L., and J. Coque. 2016. How is a food bank managed? Different profiles in Spain. Agriculture and Human Values 33 (1): 89–100.

Greenspan, I. 2014. How can Bourdieu’s theory of capital benefit the understanding of advocacy NGOs? Theoretical framework and empirical illustration. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 43 (1): 99–120.

Hilgers, M., and E. Mangez. 2015. Bourdieu’s theory of social fields: concepts and applications. London: Routledge.

Hirth, S., Oncini, F., Boons, F., & Doherty, B. 2022. Building back normal? An investigation of practice changes in the charitable and on-the-go food provision sectors through COVID-19. Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy 18 (1): 410–427.

IFAN. 2018. Our response to the Asda, Fareshare & Trussell Trust announcement. Available at: http://old.ekklesia.co.uk/node/25186.

Jonas, A. E. 2006. Pro scale: further reflections on the ‘scale debate’ in human geography. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 31 (3): 399–406.

Kluttz, D., N., and N. Fligstein. 2016. Varieties of sociological field theory. pp. 185–204. In Handbook of contemporary sociological theory, edited by S. Abrutyn. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International.

Krause, M. 2018. How fields vary. The British Journal of Sociology 69 (1): 3–22.

Kungl, G., and D. J. Hess. 2021. Sustainability transitions and strategic action fields: a literature review and discussion. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 38: 22–33.

Lambie-Mumford, H. 2013. ‘Every town should have one’: emergency food banking in the UK. Journal of Social Policy 42 (1): 73–89.

Lambie-Mumford, H., and T. Silvasti. 2020. The rise of food charity in Europe: the role of advocacy planning. Bristol: Policy Press.

Lang, R., and D. Mullins. 2020. Field emergence in civil society: a theoretical framework and its application to community-led housing organisations in England. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 31 (1): 184–200.

Lohnes, J., and B. Wilson. 2018. Bailing out the food banks? Hunger relief, food waste, and crisis in Central Appalachia. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 50 (2): 350–369.

Loopstra, R., A. Reeves, D. Taylor-Robinson, B. Barr, M. McKee, and D. Stuckler. 2015. Austerity, sanctions, and the rise of food banks in the UK. British Medical Journal 350: h1775.

Loopstra, R., J. Fledderjohann, A. Reeves, and D. Stuckler. 2018. Impact of welfare benefit sanctioning on food insecurity: a dynamic cross-area study of food bank usage in the UK. Journal of Social Policy 47 (3): 437–457.

Loopstra, R., H. Lambie-Mumford, and J. Fledderjohann. 2019. Food bank operational characteristics and rates of food bank use across Britain. Bmc Public Health 19 (1): 1–10.

Manchester City Council. 2020. Helpline has received 10,000 requests for food support since the COVID-19 crisis began. https://tinyurl.com/y5wezjsk.

Marston, S. A., I. I. I. Jones, J. P., & K. Woodward. 2005. Human geography without scale. Transactions of the institute of British Geographers 30 (4): 416–432.

May, J., A. Williams, P. Cloke, and L. Cherry. 2019. Welfare convergence, bureaucracy, and moral distancing at the food bank. Antipode 51 (4): 1251–1275.

May, J., A. Williams, P. Cloke, and L. Cherry. 2020. Food banks and the production of scarcity. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 45 (1): 208–222.

Mills, C. W. 2000. The sociological imagination. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Möller, C. 2021. Discipline and feed: Food banks, pastoral power, and the medicalisation of poverty in the UK. Sociological Research Online 26 (4): 853–870.

Moraes, C., M. G. McEachern, A. Gibbons, and L. Scullion. 2021. Understanding lived experiences of food insecurity through a paraliminality lens. Sociology, online first.

Oncini, F. 2021. Food support provision in COVID-19 times: a mixed method study based in Greater Manchester. Agriculture and Human Values 38 (4): 1201–1213.

Oncini, F. 2022a. Food support provision in COVID-19 times: Organizational data from Greater Manchester. Data in Brief 41: 107918.

Oncini, F. 2022b. Hunger bonds: boundaries and bridges in the charitable food provision field. Sociology, Online first.

Oncini, F. & Ciordia, A. 2023. Strategic action fields through digital network data: an examination of charitable food provision in Greater Manchester. SocArXiv, 30 June 2023. Available at: https://osf.io/preprints/socarxiv/qu2mz/.

Ostrower, F. 1995. Why the wealthy give: the culture of elite philanthropy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Parsons, E., T. Kearney, E. Surman, B. Cappellini, S. Moffat, V. Harman, and K. Scheurenbrand. 2021. Who really cares? Introducing an ‘ethics of care’ to debates on transformative value co-creation. Journal of Business Research 122: 794–804.

Patrick, R., K. Garthwaite, G. Page, M. Power, and K. Pybus. 2021. Budget 2021: a missed opportunity to make permanent the £20 increase to Universal Credit. British Politics and Policy at LSE. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/5dcbjtsn.

Poppendieck, J. 1994. Dilemmas of emergency food: A guide for the perplexed. Agriculture and Human Values 11: 69–76.

Power, M., and N. Small. 2022. Disciplinary and pastoral power, food and poverty in late-modernity. Critical Social Policy 42 (1): 43–63.

Power, M., B. Doherty, K. Pybus, and K. Pickett. 2020. How COVID-19 has exposed inequalities in the UK food system: the case of UK food and poverty. Emerald Open Research 2: 11.

Purdam, K., E. A. Garratt, and A. Esmail. 2016. Hungry? Food insecurity, social stigma and embarrassment in the UK. Sociology 50 (6): 1072–1088.

Reeves, A., and R. Loopstra. 2020. The continuing effects of welfare reform on food bank use in the UK: the roll-out of universal credit. Journal of Social Policy 50 (4): 788–780.

Rizvi, A., R. Wasfi, A. Enns, and E. Kristjansson. 2021. The impact of novel and traditional food bank approaches on food insecurity: a longitudinal study in Ottawa, Canada. Bmc Public Health 21 (1): 1–16.

Sanderson, M. R. 2020. Here we are: Agriculture and Human values in the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Agriculture and Human Values 37 (3): 515–516.

Schmidt-Wellenburg, C., and S. Bernhard, eds. 2020. Charting transnational fields: methodology for a political sociology of knowledge. Routledge.

Spicer, J., T. Kay, and M. Ganz. 2019. Social entrepreneurship as field encroachment: how a neoliberal social movement constructed a new field. Socio-Economic Review 17 (1): 195–227.

Strong, S. 2019. The vital politics of foodbanking: hunger, austerity, biopower. Political Geography 75: 102053.

Swords, A. 2019. Action research on organizational change with the Food Bank of the Southern Tier: a regional food bank’s efforts to move beyond charity. Agriculture and Human Values 36: 849–865.

Tarasuk, V., Fafard St-Germain, A. A., & R. Loopstra. 2020. The relationship between food banks and food insecurity: insights from Canada. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 31 (5): 841–852.

The bread and butter thing. 2023. Impact report 2022. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/bdea7ztk.

Tikka, V. 2019. Charitable food aid in Finland: from a social issue to an environmental solution. Agriculture and human values 36 (2): 341–352.

Trussell Trust. 2020. Food banks report record spike in need as coalition of anti-poverty charities call for strong lifeline to be thrown to anyone who needs it. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/jxwnd2ca.

Trussell Trust. 2021. How food banks work. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/3nej7n2s.

UK Government. 2020a. Regulatory and Risk Framework. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/344fujau.

UK Government. 2020b. Cash support for food redistribution during coronavirus outbreak. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/yx9dz9cy.

Warshawsky, D. N. 2022. Food insecurity and the covid pandemic: uneven impacts for food bank systems in Europe. Agriculture and Human Values, 1–19.

Williams, A., P. Cloke, J. May, and M. Goodwin. 2016. Contested space: the contradictory political dynamics of food banking in the UK. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 48 (11): 2291–2316.

Your Local Pantry. 2021. About us. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/ye3sp6fx.

Acknowledgements

The author is much obliged to the Great Manchester Poverty Action and the Food Operations Group for their help throughout the fieldwork. Many thanks also to Letizia Nardi for creating Figure 2.

Funding

This research was supported by the H2020 Marie Skłodowska-Curie Fellowship (Grant Number 838965), the Japanese Society for the Promotion of Science (Grant-in-Aid for JSPS Research Fellow 22F22755), and the Sustainable Consumption Institute (University of Manchester) internal fund.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author reports there are no competing interests to declare.

Additional information