Abstract

Scholars have demonstrated that common ways of performing charitable food aid in high-income countries maintain a powerless and alienated status of recipients. Aiming to protect the dignity of recipients, alternative forms of food aid have taken shape. However, an in-depth understanding of dignity in the context of food aid is missing. We undertook a scoping review to outline ways in which the dignity of recipients is violated or protected across various forms of food aid in high-income countries. By bringing scientific results together through a social dignity lens, this paper offers a complex understanding of dignity in the context of food aid. The online database Scopus was used to identify scientific literature addressing food aid in relation to the dignity of recipients in high-income countries. The final selection included 37 articles representing eight forms of food aid in twelve countries. Across diverse forms of food aid, the selected studies report signs of (in)dignity concerning five dimensions: access to food aid, social interactions, the food, the physical space, and needs beyond food. Research gaps are found in the diversity of forms of food aid studied, and the identification of social standards important for recipients. Bringing the results of 37 articles together through a social dignity lens articulates the complex and plural ways in which the dignity of recipients is violated or protected. In addition, this review has demonstrated the usefulness of a social dignity lens to understand dignity across and in particular food aid contexts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Household food insecurity is a significant public health concern in high-income countries (Loopstra 2018). Until governments address the socio-economic and political factors which perpetuate poverty in high-income countries, third sector food aid will contribute to an immediate response to the urgent need in households (Tarasuk and Eakin 2005; Thang 2008; Riches and Silvasti 2014). Within this paper we focus on those third sector responses to food insecurity, which we define as: initiatives that are non-profit-distributing emergency food, privately organized (institutionally separate from the government) and at least in part run by volunteers. This is based on the characteristics of third sector organizations as described by Salamon and Anheier (1997).

In many high-income countries, foodbanks represent a prominent form of emergency food provision in the third sector (Dagdeviren et al. 2019; Berardi et al. 2021). However, several studies have demonstrated that foodbanks handing out pre-arranged food parcels can cause recipients to experience feelings of shame and humiliation and a status of being a ‘lesser’ citizen (Power 2011; Riches and Silvasti 2014; Horst et al. 2014; Garthwaite 2016). Such aid provisioning maintains and emphasizes a powerless and alienated status of food insecure citizens (Douglas et al. 2015; Williams et al. 2016; Middleton et al. 2018).

Against the backdrop of these critiques, several foodbanks changed their format, and during the last decade new third sector initiatives—for example social groceries—have emerged aiming to provide food in a more dignified way (Wakefield et al. 2013; Galli et al. 2016; Vissing et al. 2017). These alternative forms of food aid cover a diversity of practices tailored to various needs of food insecure people in different local contexts. Even when organizations agree on an aim to empower people in a situation of food insecurity and create ‘a socially just food system’, they vary in their regulatory controls, eligibility processes, degree of individualized care, reliance on surplus food or donations, and other features (Wakefield et al. 2013; Vissing et al. 2017; Booth et al. 2018a).

Within this changing landscape of third sector food aid in high-income countries, insights about how aspects of food aid violate or protect the dignity of recipients are scattered. Various studies provide an understanding of the impact of a single organization—and the specific practices of food aid—on aspects relevant for the dignity of receivers, such as social stigma (Edwards 2021) or abilities to uphold consumer norms (Bedore 2018; Andriessen et al. 2020; McNaughton et al. 2021). A few studies compare multiple forms of third sector food aid within one country or city and analyse their transformative meaning within the changing scenery of food aid in high-income countries (Wakefield et al. 2013; Booth et al. 2018b; Hebinck et al. 2018). Additionally, Middleton et al. (2018) conducted an international scoping review providing insight in the user perspectives of foodbanks based on twenty qualitative studies. Yet, a review with an international scope including diverse forms of third sector food aid (e.g. social groceries, community gardens, meal programs) is missing, which is needed to accelerate a diverse, plural and complex understanding of how ways of doing food aid impact the dignity of recipients. Therefore, we aim to bring together scientific results about the dignity of food aid recipients addressing diverse forms of food aid in different high-income countries.

Methods

In order to investigate what scientific studies show about ways in which the dignity of recipients is violated or protected in the diverse contexts of food aid, we conducted a scoping review. The method of a scoping review enables us to scan the broad field of research addressing various forms of food aid in different Western high-income countries in a rigorous way, and to systematically identify and select articles based on explicated in- and exclusion criteria. Moreover, a scoping review of scientific literature allows us to find research gaps for a better understanding of dignity in the context of food aid, and to point out potential future research questions (Arksey and O'Malley 2005; Munn et al. 2018).

To design this scoping review, we used the framework developed by Arksey and O’Malley (2005) for scoping reviews. This framework consists of five different stages: (1) identifying the research question, (2) identifying relevant studies, (3) study selection, (4) charting the data, and (5) collating, summarizing, and reporting the results. For this research, we introduced an extra step after we identified the research question (stage 1) in order to identify relevant studies and analyse the literature, which we call ‘operationalizing dignity’. We will explicate per stage what this meant for this research.

Stage 1: research question

This review was guided by the following question: What is known in scientific literature about ways in which the dignity of recipients is violated and protected in diverse contexts of third sector food aid in different Western high-income countries?

Stage 2: operationalizing dignity

As a concept studied in various fields, scholars have differentiated two main understandings of dignity across disciplines: (1) dignity as a principle, an inalienable value inherent to being human, and (2) dignity as a concern in particular social situations in which it can be ‘taken away’, harmed, or raised (e.g. Jacobson 2007; Leget 2013; Killmister 2017; Pols et al. 2018). To capture how situations of food aid impact the dignity of receivers, we focused on the latter, referred to by Jacobson (2007) as social dignity.

Social scientists and philosophers point to different types of social dignity, e.g. a type of dignity ascribed to an individual’s status in a social hierarchy (Meyer 2001; Nordenfelt 2004; Jacobson 2012), the moral value ascribed to one’s actions and attitudes (Nordenfelt 2004) and the integrity and autonomy people attach to themselves as a consequence of the way other people approach them (Nordenfelt 2003, 2004). Killmister (2017) manifests that these different forms of dignity are all about being subject to and upholding relevant normative standards, which can either have a subjective or a communal source. These explanations of social dignity help to understand when people’s social dignity is at stake, e.g. situations that affect their social status, moral judgements, and autonomy and integrity, and in relation to possibilities to uphold social norms.

To further recognize such situations, we used the framework developed by Jacobson (2009) with emotions, feelings and social processes that indicate dignity violation or promotion. In this framework, social processes like social exclusion, deprivation, dependence, restriction, suspicion and discrimination are determined as signs of dignity violation, and social processes like independence, empowerment, recognition, concealment, control, compassion and contribution are remarked as signs of dignity promotion (Jacobson 2009). Besides these social processes, Jacobson (2009) points to specific emotions and feelings as consequences of dignity violation or promotion. Dignity violations for instance result in embarrassment, anger, shame, humiliation, guilt, and degradation (feeling “worthless”, feeling “like a failure”).

In this scoping review, we used the types of social dignity as well as the framework of Jacobson (2009) to identify relevant studies and recognize sections in the selected literature as situations where dignity is at stake. This was needed because the impact of ways of food aid on recipients is often described without direct reference to the term dignity but by a diversity of these signs of dignity violation and protection.

Stage 3: identifying relevant studies

The search was implemented on April 9, 2021, in the electronic database Scopus. We selected the database Scopus based on advice of an experienced librarian and because of its multidisciplinary scope and its wide coverage of studies in the social sciences. Other electronic databases considered were Web of Science and SocIndex. Because of the immense overlap between these databases it was decided to focus on Scopus only.

To obtain a list of potential sources in Scopus, we developed an extensive query (see Supplementary Information 1) based on a preliminary literature scan and in consultation with a research librarian. The database was searched for literature written in English, with a combination of terms related to third sector food aid, food insecurity, Western high-income countries and dignity.

To find articles about third sector food aid, it was decided to include all the terms encountered for third sector food aid during a preliminary scan, such as foodbank, food hub, and social supermarket. This resulted in relevant articles which were not identified when only using general terms such as food aid, food assistance, and food service. Hereby we conceptualized food aid in a broad way, namely as initiatives contributing to the food supply of households experiencing poverty by increasing their access to food, irrespective of an explicit aim by the initiative to address food insecurity. Based on this conceptualization of food aid, community gardens can for instance also be understood as food aid because several studies have shown that community gardens support food security by providing low-income gardeners with a significant proportion of their food supply (Armstrong 2000; Wakefield et al. 2007). We choose for this broad conceptualization of food aid to move beyond the notions of (in)dignity at settings generally understood as food aid (often characterized by charity), and thereby contribute to a more diverse and complex understanding of dignity in food aid settings.

Another aspect that contributed to an extensive query was the inclusion criteria related to Western high-income countries. This specification of countries was crucial in our query because food aid has been extensively studied in non-Western, low or middle-income countries. To accomplish this, we combined a list of Western countries as provided by the data scientist Trubetskoy (2017), defined by their cultural and ethical values, with a list of high-income countries as classified by the World Bank (2021). By doing so, we tailored our query to include specific countries and terms referring to their inhabitants. Limiting our scope to Western high-income countries was necessary due to our contextual approach to dignity. Nevertheless, we do not intend to imply in any way that these Western high-income countries are uniform, as they encompass a range of welfare systems characterized by varying degrees of social assistance and distinct roles for third sector involvement. Furthermore, it is vital to recognize that focussing exclusively on Western high-income countries does not diminish the richness and diversity of norms and values performed within food aid settings, e.g. those from Western, non-Western, and various religious backgrounds.

Thirdly, to identify studies addressing issues related to the social dignity of recipients even when the term dignity itself isn’t used, we determined a list of terms that are signs of dignity violation or promotion based on the theoretical and empirical understandings of social dignity we found in stage 2.

Stage 4: study selection

The results of the search query were uploaded into the EndNote reference manager and independently assessed by two reviewers (i.e. the first author of this paper and a second reviewer with a Master’s Degree in Cultural Anthropology with expertise on Dutch foodbanks) to decide on their in—or exclusion based on a three-step screening process: (1) title, (2) abstract and (3) full-text. Studies were included or eliminated based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria described in Table 1. Studies were eligible for inclusion if they addressed third sector food aid in a Western high-income country in relation to signs of dignity violation or protection. Papers were excluded if they did not focus on third sector food aid and when they did not contain qualitative and first-hand data. In doubtful cases, we included the article for a full-text screening. After each step, differences in the selection process were identified and discussed to reach an agreement about which articles to include for the next step.

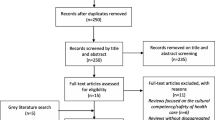

A total of 1533 articles were identified in the database search. After the full-text screening, 60 articles were included, all addressing food aid in relation to signs of recipients’ dignity (see Fig. 1). In favour of a relevant and feasible selection of articles for in-depth analysis, we made a further selection out of these 60 articles. We selected 34 articles that constituted a good representation of the various forms of food aid, different countries, diverse study populations and types of social dignity addressed within the 60 articles. For example, when an article addressed the issue of stigmatization at a foodbank in the UK, and another article provided a more detailed analysis of this issue at foodbanks in the UK, we excluded the former article from our selection. In this way we did not lose insights related to a specific country (the UK), a particular form of food aid (foodbanks), or a particular form of social dignity (stigmatization). We also critically reflected on the full-texts based on how elaborate the part of the results section was that indicated signs of social dignity in relation to the food aid setting.

Flowchart of study selection process. n refers to the number of papers. E + number = specific exclusion criteria corresponding with Table 1

Due to our comprehensive approach to third sector food aid and the multitude of terms used to address issues of (in)dignity, it was likely that our query in Scopus had blind-spots. Therefore we additionally screened the 60 reference lists of the initially selected articles to identify relevant literature not covered by the database search in Scopus. Twenty-five titles were selected out of these reference lists, of which 13 were included after a full-text screening applying the exclusion criteria. One of the studies identified through this additional screening was the article by McKay et al. (2018). We did not identify this article in Scopus because it is about a food aid initiative called ‘The Food Justice Truck’—a name that does not match with one of the terms for third sector food aid included in our query. Three articles out of these additional 13 were included in the final selection of articles for the review, based on a similar critical selection as executed among the 60 articles from the database screening. As a result, a total of 37 articles were included in the current scoping review (see Fig. 1).

Stage 5: charting the data

The data we charted included texts that reflected the perspectives of organizers of food aid, volunteers, and recipients as well as observations and interpretations of the researchers, because they all contribute to understand the plural and complex meanings of dignity in the context of food aid. The authors analysed the results of the included papers through a process of coding. To recognize relevant results in the articles, we used the theories about social dignity as described in "Stage 2: operationalizing dignity" as background knowledge. Based on these theories we coded pieces of texts in the selected literature reflecting issues that could be linked to social status, social norms, moral judgements, autonomy or integrity (Meyer 2001; Nordenfelt 2004; Jacobson 2012). Furthermore, the social processes and feelings described by Jacobson (2009) to characterize dignity were also used to identify relevant results. We categorized these codes into signs of dignity protection (DP) or dignity violation (DV). In addition, we added inductive codes that captured particular signs of (in)dignity as pointed out in the selected papers as important in the context of food aid, such as ‘reciprocity’ under the category of dignity protection (DP) and ‘being grateful’ as a sign of dignity violation (DV). Eventually, 50 codes were developed reflecting signs of dignity violation (23 codes) or protection (27 codes).

Additionally, we inductively identified aspects in food aid that are described in relation to these dignity violations or protections. So, when coding a piece of text in an article with a sign of (in)dignity, we attached a second code referring to an aspect in food aid described in relation to the dignity violation or protection. This resulted in a code tree with 26 codes corresponding to aspects of food aid noticed in the selected studies as important for the dignity of receivers (see Supplementary Information 2). Clustering these 26 aspects of food aid, the researchers constructed five dimensions of food aid important for the dignity of recipients: (1) the access to food aid, (2) social interactions, (3) the food, (4) the physical space, and (5) needs beyond food. The software Atlas.ti version 9 was used to assist the coding process and extraction of quotes and themes.

Results

Characteristics of included studies

This review includes 37 articles, all based on qualitative, first-hand data. All the selected articles were published between 2000 and 2021, of which 21 articles between 2018 and 2021. Most of the studies are conducted in the USA (10 articles), Australia (8 articles), the UK (7 articles) and Canada (5 articles), and the remaining seven papers contain studies in different European countries (see Table 2). The three main forms of food aid reflected by the studies are food pantries/foodbanks (in 15 articles), meal programs/community kitchens (in 11 articles), and foodbanks with a shop-setting/social supermarkets (in 10 articles), with four studies addressing all three of these ways of food aid (Kravva 2014; Booth et al. 2018a, b; Herrington and Mix 2021). The other papers address other forms of food aid, such as (community) gardens and vouchers for a farmers market (see Table 2). Twenty-three of the articles focus on recipients, of which four on specific groups (i.e. children (Dayle et al. 2000; Shinwell et al. 2021), people seeking asylum (McKay et al. 2018), and African Americans (Kolavalli 2019)), ten studies include perspectives of both recipients and volunteers, and three studies focus only on the perspectives of volunteers (Rombach et al. 2018; Rowland et al. 2018; May et al. 2020). One study focuses on non-users (Fong et al. 2016), providing unique insights in how food aid can threaten the dignity of low-income individuals in such ways that it results in not wanting to use food aid at all (see Table 2).

Aspects of food aid important for the dignity of receivers

Below we outline five dimensions that cover the aspects in food aid which are described in the selected literature as important for the dignity of recipients, either related to dignity violation or dignity protection. These aspects transcend the eight different types of food aid included in this review, by highlighting components that are part of multiple of these forms of food aid, such as the eligibility assessment and the food source. Furthermore, it is imperative to recognize that while these aspects are integral to the immediate environment in which food aid recipients are served, they are influenced by wider organizational frameworks, including donor relationships and interactions with the state.

Access to food aid

The first dimension that we were able to create is access to food aid. This dimension concerns the rules and regulations performed by organizations that affect recipients’ access to food aid, such as eligibility criteria, opening hours and if the food is offered for ‘free’ or for a (highly discounted) price (see Supplementary Information 3—Data charting table). The selected studies indicate that such rules and regulations constitute the dignity of recipients in different ways: by performing a social hierarchy of ‘deservingness’, by reinforcing moral judgements, and by violating recipient’s integrity. Bringing the insights of different studies together also helps us to demonstrate the complexity and plurality of what it means to provide access to food aid in a dignified way. We will illustrate this by means of one of the aspect of food aid covered by the dimension ‘access to food aid’, namely eligibility assessments.

Eligibility criteria maintained by initiatives to decide who qualifies to receive food aid are marked in the selected literature as significant for the social dignity of receivers. On the one hand, several of the selected papers demonstrate how such criteria violate the dignity of recipients. Four studies conducted in three different countries (Canada, Australia and Greece) highlight that strict criteria for food aid, whereby the organization asks for disclosure of one’s tight financial situation and debts, are experienced by recipients as degrading and embarrassing (Kravva 2014; Organ et al. 2014; Bedore 2018; McNaughton et al. 2021). In most of the selected papers eligibility criteria are discussed in relation to moral judgements and social hierarchy. Bedore (2018) shows for example in her study about a retail-based community food project in Canada how disclosure of one’s financial situation as part of strict eligibility criteria can provoke moral judgments of one’s behaviour, such as being criticized about how one’s budget is spent. In addition, in seven articles eligibility assessments are discussed as violating the dignity of recipients by provoking an informal hierarchy related to rights, as it ranks food insecure people as ‘deserving’ or ‘undeserving’ (Fong et al. 2016; Williams et al. 2016; Bedore 2018; May et al. 2019, 2020; Möller 2021; Surman et al. 2021).

In accordance with cases describing strict eligibility criteria as violating the dignity of recipients, ten studies show that relaxed requirements (i.e. with regard to paperwork), or a program open to everyone, protects the dignity of food aid recipients (Engler-Stringer and Berenbaum 2007; Levkoe and Wakefield 2011; Allen et al. 2014; Bruce et al. 2017; Bedore 2018; Booth et al. 2018a, b; Gómez Garrido et al. 2019; Edwards 2021; Herrington and Mix 2021; Shinwell et al. 2021). These papers indicate that no requirements for recipients to disclose their financial situation or other personal information communicates trust, reduces feelings of shame and fosters a sense of social inclusion. It is also manifested in the reviewed studies that initiatives that offer food for everyone—not limited to those who experience food insecurity—increase access to food (Bruce et al. 2017; Gómez Garrido et al. 2019) and help people who experience food insecurity to move away from an identification of ‘those in need’ (Engler-Stringer and Berenbaum 2007; May et al. 2019; Edwards 2021; Shinwell et al. 2021; Surman et al. 2021). However, five studies also show that when it is not strongly manifested and enacted that everyone is welcome, regardless of one’s financial situation, this can create obscurity about who is eligible with space for moral judgements about one’s ‘deservingness’ and expressions of gratefulness and respect (Organ et al. 2014; Fong et al. 2016; Williams et al. 2016; Booth et al. 2018a; May et al. 2019).

These insights seem to communicate a clear message, namely that strict eligibility criteria performed by food aid organizations violate the dignity of receivers. However, bringing the results of various studies together also demonstrates the plural—sometimes contradictory—ways in which eligibility assessments affect the dignity of recipients. While eligibility assessments mark out those in ‘genuine need’ associated with a low social status, at the same time six of the included studies examining four different forms of food aid (Social supermarkets, foodbanks, education program, vouchers for a farmers market) indicate that food aid initiatives that are only accessible for people experiencing food insecurity can be a safe space for recipients to share experiences with food insecurity, which reduces feelings of shame and fosters a sense of community (Dailey et al. 2015; Meiklejohn et al. 2017; Gómez Garrido et al. 2019; Andriessen et al. 2020; Herrington and Mix 2021; McNaughton et al. 2021). These results show that eligibility criteria can also support a setting that protects the dignity of receivers. While these insights show the complexity of what it means to regulate the access to food aid in a way that protects the dignity of food insecure people, they do emphasize that the issue of who has access to food aid has a strong impact on the dignity of recipients across diverse Western, high-income countries.

As pointed out in the literature, the impact of eligibility assessments on the social dignity of recipients is often explained in relation to certain moral judgements and social hierarchies. Such moralities and hierarchies are not shaped by the eligibility criteria in and of itself, but are performed through many aspects in the context of food aid and in other spaces and places of society. Moralities around ‘deservingness’ with judgements about recipients’ gratefulness and responsibility are for example also described in the reviewed papers in relation to the type of exchange through which food aid is handed out, which we will address in the next section.

Social interactions when receiving food aid

Many of the signs of violation or protection of recipients’ dignity in the selected articles are discussed in relation to the social interactions between food aid recipients as well as between recipients and volunteers or employees. Various of the selected studies suggest that how people interact, and the different roles assigned to recipients, has a major influence on the moralities and social hierarchies performed at a food aid organisation and affects recipients’ integrity and autonomy. In this section we will describe aspects of the way in which food aid is organized that are highlighted in the selected literature as setting the stage for certain roles and interactions (See Supplementary Information 2—Data charting table).

Sixteen of the selected papers show that the type of exchange can reinforce or counteract a social hierarchy between recipients and volunteers (Remley et al. 2010; Van der Horst et al. 2014; Chan et al. 2016; Bedore 2018; Booth et al. 2018a, b; McKay et al. 2018; Rowland et al. 2018; Bowe et al. 2019; Gómez Garrido et al. 2019; Andriessen et al. 2020; Diekmann et al. 2020; May et al. 2020; Herrington and Mix 2021; McNaughton et al. 2021; Smith and Harvey 2021). Charitable giving is described in these studies as a way of exchange that provokes harmful interactions. Foodbanks, for example, typically distribute ‘free’ food, whereby people don’t get the opportunity to give something in exchange. Ten studies indicate that such ‘free’ gifts come with moralities of receivers being grateful and not picky, reflected in attitudes such as "beggars can’t be choosers" (Kravva 2014; Van der Horst et al. 2014; Bedore 2018; Booth et al. 2018a, b; McKay et al. 2018; May et al. 2020; McNaughton et al. 2021; Möller 2021; Surman et al. 2021). These moralities reflect the hierarchical interactions between givers and receivers of free food, as documented in four of these studies (Bedore 2018; Booth et al. 2018a; McKay et al. 2018; McNaughton et al. 2021). Some papers also describe that such a hierarchy can be supported by rules and regulations, for instance when volunteers make food choices on behalf of the recipients (Booth et al. 2018a; McKay et al. 2018; Möller 2021) and when recipients are not allowed to trade products (Kolavalli 2019). Van der Horst et al. (2014) and Rombach et al. (2018) explain that such hierarchical divisions between givers and receivers of a charitable gift can reinforce feelings of shame, gratitude and anger.

Several of the reviewed studies emphasize acts of reciprocity as means to counter these experienced debts when receiving a charitable gift. In these articles, it is argued that through an act of paying in a shop setting, exchanging produce in gardens, or participating as a volunteer as different enactments of reciprocity, recipients of food aid experience less shame and embarrassment, and it builds a sense of solidarity (Chan et al. 2016; Bedore 2018; Booth et al. 2018a, b; Bowe et al. 2019; Gómez Garrido et al. 2019; Andriessen et al. 2020; Diekmann et al. 2020; Herrington and Mix 2021; Smith and Harvey 2021). Related to this are opportunities for recipients to participate in the organization of food aid, which is emphasized by eight studies as a way to protect the dignity of recipients (Levkoe and Wakefield 2011; Allen et al. 2014; Shamasunder et al. 2015; Chan et al. 2016; Gómez Garrido et al. 2019; Edwards 2021; Herrington and Mix 2021; Smith and Harvey 2021). Herrington and Mix (2021) argue that volunteering can enable recipients to “give something back” as a relief from a moral judgment of “just” receiving a charitable gift. In this way, opportunities to uphold norms of reciprocity can enable recipients to move away from a low social status as gift receiver of food aid.

Additionally, the practice of product choice is indicated by eight of the selected articles as promoting respectful interactions between volunteers and recipients of food aid (Remley et al. 2010; Booth et al. 2018a; McKay et al. 2018; Rowland et al. 2018; Bowe et al. 2019; Andriessen et al. 2020; May et al. 2020; Herrington and Mix 2021). Food aid initiatives organized as a shop, whereby product choice is manifested as a norm, are determined by Andriessen et al. (2020) and Bedore (2018) as settings that allow clients to save face and promote autonomy. It possibly conceals interactions of charitable giving and reliefs food aid receivers from a single identification as a food aid receiver, since they also experience an identity as a customer at such shop settings (Bedore 2018; Andriessen et al. 2020). However, McNaughton et al. (2021) show in their case study about a food hub with a supermarket style that this form of food aid still violates the dignity of recipients through disciplinary capacities (e.g. teaching recipients how to spend their budgets in ‘a responsible way’) and harmful staff attitudes. In five of the selected studies it is claimed that friendly, caring, empathic and inclusive attitudes of volunteers are essential to protect the dignity of recipients (Allen et al. 2014; Booth et al. 2018a; Bruce et al. 2017; Herrington & Mix 2021; McNaughton et al. 2021).

Overall, when we look at aspects in food aid that set the stage for certain social interactions, the selected literature corresponds in a claim that the exchange of food through charitable giving undermines the dignity of recipients by establishing a social hierarchy between givers and receivers. At the same time, the selected papers argue that these negative consequences can be mitigated through practices of reciprocity, providing recipients with autonomy in decision-making, demonstrating compassion and care among volunteers and opportunities to interact with other recipients in a safe space. However, as explained above, combining insights of studies about food aid with a shop setting emphasizes how the impact of a way of providing food aid on the dignity of recipients should always be understood through the entanglement of various aspects influencing recipients’ social dignity.

The food

A third dimension identified in the reviewed studies in relation to signs of dignity violation or protection is the food provided by food aid organizations. In this section, we will explain two aspects related to the food people can access through food aid that are described in the selected articles as important to understand the impact on recipients’ social dignity: the appropriateness and the source.

Twenty-four of the selected studies draw attention to the appropriateness of the food provided by food aid organizations in relation to emotions and social processes that indicate an impact on the dignity of recipients (Dayle et al. 2000; Engler-Stringer and Berenbaum 2007; Remley et al. 2010; Levkoe and Wakefield 2011; Allen et al. 2014; Kravva 2014; Organ et al. 2014; Van der Horst et al. 2014; Fong et al. 2016; Bedore 2018; Booth et al. 2018a, b; McKay et al. 2018; Rowland et al. 2018; Bowe et al. 2019; Kolavalli 2019; Lindberg et al. 2019; Andriessen et al. 2020; May et al. 2020; Edwards 2021; Herrington and Mix 2021; McNaughton et al. 2021; Shinwell et al. 2021; Smith and Harvey 2021). Based on perspectives of organizers, volunteers and recipients, these studies suggest that food of poor quality, in limited amount, being unhealthy (e.g. with high fat and sugar contents), being culturally inappropriate, and not suiting individual preferences and dietary needs, heightens the experience of poverty among receivers, disables them to express their identity and has a negative impact on their self-worth. At the same time, these papers indicate that provision of fresh, organic, healthy, and culturally appropriate food, and food convenient for special diets, potentially protects the dignity of food aid recipients. While personal, nutritional needs play a role here, the papers in this review show that what it means to offer appropriate food is deeply enlaced with social norms and values. This is for example captured by the following explanation by May et al. (2020, pp. 217–218) about the food offered by a foodbank trying to enable “clients to re-identify with normal(ising) consumer behaviour”:

An emphasis is placed on providing people with recognized brands, rather than own‐brand, wholesale, or surplus food so as not to re‐enforce a sense of thrift or any sense that foodbanks supply only “surplus food to surplus people”.

In their study about foodbanks in the UK, May et al. (2020) discuss how own-brand, wholesale and surplus food refers to a common understanding that this is associated with a lower social status than products of recognized brand. Other social standards that the studies in this review indicate to be significant for the appropriateness of food are related to a role as food provider (Dayle et al. 2000; Booth et al. 2018a, b; Herrington and Mix 2021; Shinwell et al. 2021; Smith and Harvey 2021). Studying various local food security initiatives in the USA, Herrington and Mix (2021) for example report the pride and sense of achievement recipients gain when they are able to provide food valued by their family members.

Some of the selected papers also indicate that organizational practices of food aid, such as the origin of the food that initiatives receive or buy and how they distribute the food, frame the abilities of recipients to obtain appropriate food. According to the source of food provided, a donated origin is described in seven articles as problematic (Remley et al. 2010; Booth et al. 2018a; McKay et al. 2018; Kolavalli 2019; May et al. 2019; McNaughton et al. 2021; Möller 2021). In three articles it is argued that food aid organizations depending on food donations from individuals and organizations have inconsistent stock, which undermines the needs of food insecure people (Remley et al. 2010; Kolavalli 2019; Möller 2021). Yet, three other papers indicate that when food aid organizations critically select the donors or vendor’s supply, just allowing healthy foods to be donated, the dignity of recipients can be protected (Levkoe and Wakefield 2011; Dailey et al. 2015; Rowland et al. 2018). The following analysis by Edwards (2021, p. 401), about a meal program in Melbourne (Australia) called ‘Open Table’, captures how healthy products can protect the social status of food insecure people:

By providing healthy meals, Open Table is able to overcome the stigma of consuming bad quality food as “second class food for second class people” Furthermore, by fostering relationships with luxury health food stores, eaters dine on a range of high quality ingredients that expand their dietary diversity, reminding them they are ‘worth it’.

While critical selection of products is described in the literature as a way to protect the dignity of recipients in terms of appropriate food, May et al. (2019) emphasize that even being supplied with healthy, more appropriate food donations can harm the dignity of recipients by detrimental interactions of charitable giving and assessments of deservingness, as explained in the "Social interactions when receiving food aid" section. This brings back attention to the interplay between the different aspects of food aid and their impact on the social dignity of recipients.

Besides that the food is often donated by companies or individuals, food sources used by third sector initiatives often also contain food that is classified as surplus food. For instance, Van der Horst et al. (2014) indicate in their study about a Dutch foodbank that receiving surplus food can negatively impact the self-worth of recipients, creating the feeling that they are receiving food that would otherwise have been given to pigs. Based on perceptions of food charity recipients in Australia about diverse forms of food aid, Booth et al. (2018a, b) state that when an initiative is based on both surplus food and food donations a paradox of abundance and restrictions can be created, with a lack of desired food and excess of undesired food. However, not all studies emphasize surplus food as a food source that violates the dignity of recipients. Based on their research in the UK about a community meal program that uses surplus food, Smith and Harvey (2021) claim that surplus food can engender expressions of abundance and generosity, and thereby reduce an expected modesty and gratefulness of recipients. It can even save their face by framing the consumption of surplus food as mutual aid (Smith and Harvey 2021).

These different meanings associated with surplus food point out how the impact of the source of food on the social dignity of recipients depends on the social norms articulated in a context of food aid. In some cases a standard of high quality food for citizens of a consumer society is stressed, associating surplus food with a low social status (Van der Horst et al. 2014; Booth et al. 2018a; May et al. 2020). In another case the consumption of surplus food contributes to fulfilling a prioritized norm of mutual aid (Smith and Harvey 2021). This review indicates that such social norms are performed through various aspects in the way food aid is provided.

The physical space of food aid

The fourth dimension is the physical space of food aid, as already touched upon in the previous sections. In this section we explain further how the physical space in the context of food aid is discussed in the selected articles as important for the dignity of recipients.

First, several studies demonstrate that the location of a food aid organization impacts the dignity of recipients. Two studies show that receiving food aid in a neighbourhood which is uncared for, hard to visit and/or where people don’t feel safe confronts them with their low social status as a food aid receiver (Haapanen 2017; Booth et al. 2018a). Vice versa, based on a study about a Finnish Breadline, Haapanen (2017) states that food aid in an area which is peaceful and well kept, protects the dignity of people when receiving food aid in terms of social status. Additionally, based on their study about meal programmes at ten Library sites in Silicon Valley (California, USA) Bruce et al. (2017) indicate that a public location not only used for the distribution of food aid, such as a public library, can relieve people from an identification as food aid receiver and reduces a sense of alienation. That a location “open to everybody” can contribute to a relief from an identification as food aid receiver is also described by Booth et al. (2018a, b) as one of the main features of food aid in the form of gift cards allowing recipients to shop at regular supermarkets. Food aid recipients who participated in the study of Booth et al. (2018a, b) about perceptions of food aid in Australia experience supermarket gift cards as less stigmatizing than food aid where they have to enter a place exclusively for food aid receivers.

Second, some of the reviewed studies point to the setting at a certain location as being vital. The studies researching social supermarkets predominantly emphasize the importance of a shop-setting for the dignity of recipients. Seven studies highlight that a shop-setting enables clients to re-identify with normalizing consumer behaviour (Bedore 2018; Booth et al. 2018a, b; Andriessen et al. 2020; May et al. 2020; Herrington and Mix 2021; McNaughton et al. 2021). Andriessen et al. (2020) and McNaughton et al. (2021) show that material aspects of such a setting contribute to this, such as a shopping trolley, shelves, shopping lanes and a checkout. However, as already explained in the "Social interactions when receiving food aid" section, food aid organized through a shop-setting does not necessarily result in more dignified experiences when it is performed through for instance disciplinary rules and enacted by volunteers communicating strong moral judgements about recipients’ shopping behaviour (McNaughton et al. 2021).

Besides a shop-setting in the context of food aid, it has been noticed that a physical division between volunteers and recipients, with clients required to wait at one side of a service counter and asked to “point but not touch” the items they want, accentuates a powerless position of food aid receivers (May et al. 2019; Möller 2021). This inferior and dependent status is also captured by the embarrassment described in four articles that recipients experience when waiting outside in a line to receive food (Remley et al. 2010; Fong et al. 2016; Haapanen 2017; Booth et al. 2018a). In addition to this impact on their standing to volunteers, Haapanen (2017) points out that a waiting line in a public space can result in irritated responses from people outside the line, reinforcing a feeling among recipients that they are unwanted.

Finally, various studies remark that the physical space can be deployed to support a sense of community and a safe, respectful atmosphere. Shared spaces, such as a community garden to take care of together (Chan et al. 2016), a community kitchen to cook and eat together (Edwards 2021), or a dining room to enjoy meals together (Allen et al. 2014; Edwards 2021; Smith and Harvey 2021; Surman et al. 2021), are appreciated for encouraging compassion between people and a sense of social inclusion. To support a respectful atmosphere, research about social eating initiatives specifically points out that it is vital to allow participants to rearrange the physical space according to their needs (Edwards 2021; Smith and Harvey 2021). As described in the following section:

Something as seemingly mundane as customers moving tables and chairs to eat with another table shows how domestic practices of agency around spatial organization can be reconstituted within public social eating initiatives; creating environments that are constructed as intimate, customizable and participative.

Conforming to the ''customizable'' environment highlighted in this section by Smith and Harvey (2021, p. 10), Edwards (2021) emphasizes the importance of not forcing people to sit together by arranging dining tables in different ways at a place where community meals are served. Another way to symbolize that participants are welcome and ‘worth it’ through the physical space is for example through details such as flowers on the tables (Edwards 2021; Smith and Harvey 2021).

These insights demonstrate that the location, the setting, and other aspects of the physical space in which food aid takes place can provoke social norms, incite moralities, and reinforce or counteract social hierarchies and thereby affect the social dignity of recipients. However, as shown in relation to the shop-setting, to stage certain norms and roles and make both volunteers and recipients believe them, these should also be performed through other aspects in the way food aid is provided, such as offering appropriate food.

Needs beyond food

The fifth dimension that comes forward when analysing signs of dignity violation and protection in the selected articles in relation to how food aid is organized, is needs beyond food. Three different aspects are described concerning needs beyond food as important for the dignity of recipients, which are: opportunities for participation, educational programs, and political activities.

As described with regards to social interactions when receiving food aid, participation of food aid receivers in the organization of food aid can reduce power dynamics between volunteers and recipients and support a sense of belonging. Yet, opportunities for recipients to participate in the organization of food aid are also pointed out as ways to foster personal pride, self-esteem and a sense of empowerment (Engler-Stringer and Berenbaum 2007; Levkoe and Wakefield 2011; Shamasunder et al. 2015; Chan et al. 2016; Meiklejohn et al. 2017; Herrington and Mix 2021). Specifically, the included research about community gardens argues that preparing and/or growing food as activities part of food aid potentially protects the dignity of receivers (Engler-Stringer and Berenbaum 2007; Levkoe and Wakefield 2011; Shamasunder et al. 2015; Chan et al. 2016; Meiklejohn et al. 2017), because it provides “a particularly empowering experience, allowing them to exercise some control over their livelihoods and the type and quality of food they and their families consumed” (Chan et al. 2016, p. 851). Additionally, in relation to a social cafe, Allen et al. (2014) demonstrate that participation in the form of shared dining with community members can equip recipients with social skills and opportunities, and increase their confidence. Moreover, in five papers it is stated that to implement participatory methods in a way that respects people's dedication, commitment and skills it is essential to offer different types of participation matching different assets and capacities for engagement (Levkoe and Wakefield 2011; Meiklejohn et al. 2017; Edwards 2021; Shinwell et al. 2021; Smith and Harvey 2021), and not to judge people on their level of participation (Edwards 2021).

Secondly, educational programs have been described both in relation to signs of dignity violation as well as dignity protection. For example, Remley et al. (2010) show that informing receivers with nutritional information about the food they get or buy can enable them to make informed choices, which increases their sense of control. At the same time, in the research of Dailey et al. (2015) nutritional education appears to increase recipient’s sense of falling short in their ability to provide healthy meals for their families. The latter clearly reflects how programs to stimulate healthy eating can accentuate a social norm participants cannot fulfil, which violates their social dignity. Another way in which educational programs possibly threaten the dignity of participants is manifested by Kolavalli (2019). In this study, a program is researched where participation in educational lessons about healthy diets is mandatory to receive food aid. Participants of this program feel underestimated in their knowledge and skills and they experience discriminating and patronizing language (Kolavalli 2019). These results emphasize the thin line between offering educational programs in a way that promotes the dignity of recipients by increasing their autonomy and integrity through knowledge and skills, and threatening their dignity by treating recipients ‘without dignity’ (i.e. patronizing them) and underlining social norms they cannot fulfil.

Third, some food aid initiatives explicitly use the food aid context as a political space. Three studies describe how fighting for policy-level solutions as a food aid organization emphasizes the structural causes of food insecurity (Levkoe and Wakefield 2011; Kravva 2014; Gómez Garrido et al. 2019). In these papers it is argued that this can cause a sense of we-ness in the fight against food poverty and can reduce discourses around poverty blaming the individual. Vice versa, Williams et al. (2016) and Möller (2021) point to texts on websites of food aid organizations harming the dignity of recipients because it amplifies negative judgements about individual performances and attitudes. In addition, Williams et al. (2016) illustrate in their paper about foodbanks in the UK how certain discourses and political positions are performed through many aspects in the way food aid is organized. They argue that the extent to which harmful discourses about food poverty are communicated when food is distributed highly depends on the political attitudes of volunteers to challenge these discourses and their commitment to reduce stigmas by means of developing understandings of people’s situations. This points out that the impact of political positions explicated by political activities in food aid settings depend on its resonation with moralities and social standards communicated through other dimensions of food aid, such as social interactions between volunteers and recipients, and eligibility assessments.

Research gaps

By bringing the results of 37 studies together, this scoping review has indicated a rich, plural and complex understanding of dignity across diverse food aid contexts. However, this review also sheds light on some major research gaps to understand the impact of the way in which food aid is provided on the dignity of recipients.

First, this review exposes that within the academic field on food aid in high-income countries there is a dominant focus on regular forms of food aid such as foodbanks. While we aimed to select studies addressing diverse forms of food aid, the majority of the papers in this review still focusses on foodbanks/food pantries. This focus frames debates about the dignity of recipients, e.g. discussing issues of deservingness, individual choice, and the impact of charitable giving. While these are vital issues to discuss, at the same time insights from alternative forms of food aid are essential to enhance debates about the dignity of food aid recipients. Academics can foster more radical transformations towards dignified food aid by paying attention to cases that challenge dominant discourses in the context of emergency food provisioning, such as charity and neoliberalism. This could mean to study food securing practices accessible for people experiencing poverty that aren’t associated with food aid in the first place, e.g. food not bombs (Parson 2014) or punk cuisine (Clark 2004). Researching such initiatives in relation to the dignity of people experiencing poverty could enrich debates in the field of food aid with a stronger body of knowledge about the impact of e.g. food sharing practices, community building, and political activities. While such aspects where touched upon in some of the selected studies, this review indicates the need for more knowledge on how alternative ways of ‘food aid’ impact the dignity of food insecure people.

Besides this gap calling for academics to study alternative forms of food provisioning, the social dignity lens used in this review helps us to articulate more directions for future research. Moving beyond a focus on forms of food aid impacting the dignity of recipients, the situational understanding of dignity explicated in this review highlights that a blueprint for dignified food aid does not exist in terms of particular practices that inherently promote recipient’s dignity. The entanglement of spaces, things, roles, and meanings in violations or protections of the dignity of food aid recipients points to the essential need to discuss dignity on the level of moralities, social hierarchies, and the autonomy (as a status and capacity) and integrity of recipients, in relation to normative values. While most of the reviewed papers already touch upon this, this scoping review articulates the necessity of this focus to create a better understanding of dignity in the context of food aid.

Following Killmister (2017), the types of dignity related to moralities, ranks, autonomy and integrity are all about being subject to and upholding relevant normative standards, which can either have a subjective or a communal source. In order to further develop our understanding of social standards relevant for the dignity of recipients in a situation of food aid, this review points to two other research gaps. The first gap concerns the identification of standards that are widely supported in communities of which many recipients are part of. Throughout the results of the selected studies a few particular social standards were stressed several times, such as protections of the dignity of food aid recipients through abilities to uphold standards of consumer society, norms of reciprocity, and being a ‘good’ parent by giving children enough, appropriate foods. Investigation to identify social standards with a communal source could contribute to mutual understandings of social dignity across diverse models of food aid. This will also provide further insight in how the social dignity of recipients across diverse forms of food aid is shaped by powerful institutions, such as neoliberal markets (Andriessen et al. 2022), the kind of welfare state (Williams et al. 2016), and dominant religions (Madeleine Salonen 2016; Power et al. 2017). While this scoping review encompassed diverse national contexts within Western high-income counties, our study was not designed to draw conclusions regarding the impact of particular welfare states on the social dignity of food aid recipients.

Secondly, there is a research gap in determining the diversity of social standards in contexts of food aid. Within the 37 articles selected for this review, seven studies analyse their results in relation to the cultural background of recipients (Remley et al. 2010; Organ et al. 2014; Chan et al. 2016; Kolavalli 2019; Diekmann et al. 2020; Edwards 2021; Herrington and Mix 2021). These studies mainly indicate that certain aspects in the way in which food aid is provided, such as gardening, product choice, halal meals and separate dining rooms for the women and children, help recipients to develop a sense of belonging and connect with their cultural identity. However, there is a lack of comprehensive investigations into the social norms important for recipients from specific cultural backgrounds and how these norms influence their dignity in the context of food aid. One significant aspect in this regard is religion. Reflecting the research gap identified in this scoping review, Salonen’s study—on Finnish foodbanks as social spaces imbued with religious meanings and practices—highlights the lack of in-depth investigations regarding “how food recipients respond and react to the religious elements that they seem likely to encounter as they seek food assistance from a religious organization” (Salonen 2016, p. 48). This observation is particularly noteworthy given the substantial role religion plays in many food provision activities, with Christian organizations and churches being predominantly visible in various European counties (Lambie-Mumford and Dowler 2015; Salonen 2016; Madeleine Power et al. 2017). Yet, the active involvement of Muslim, Sikh and Jewish groups in addressing food insecurity should also be acknowledged (Lambie-Mumford & Dowler 2015; Salonen 2016; Madeleine Power et al. 2017). Exploring the diverse religious meanings and practices in food aid contexts could significantly contribute to cultural sensitive understandings of dignity in the context of food aid.

Additionally, none of the reviewed papers addresses social standards in relation to gender, or provides an understanding of dignity in terms of intersections between race, gender, religion and other identities. Hereby it would also be vital to include aspects part of the transcendent experiences of poverty, such as (mental) health, employment, housing and reliability of social security, as well as intergenerational contexts of poverty. Related to this gap in the diversity of social standards food aid recipients are subject to, are issues of racism, sexism and discrimination in the context of food aid. As pointed out by Maddy Power (2022, p. 2) in her book ‘hunger, whiteness and religion in neoliberal Britain’, investigation of these issues is vital, because “the lived experience of food insecurity, like that of food aid, is shaped not only by neoliberal norms, but by gendered, racial and religious identities (and the intersections between them)”.

Strengths and limitations

This scoping review aims to enhance transformations in third sector food aid to protect the dignity of those who receive it. The findings of this review offer valuable insights into five dimensions of food aid that significantly influence the dignity of recipients across diverse forms of food aid in various Western, high-income countries. By adopting a social dignity lens, this review takes an initial step in illustrating how the dignity of food aid recipients should be understood in situations where their social standing, moral assessments, autonomy, and integrity are challenged. Furthermore, this lens sheds light on the intricate connection between these aspects and the broader objective of upholding social norms.

While we believe the social dignity lens is valuable for developing in-depth and context-specific understandings of dignity within food aid settings, it is crucial to acknowledge that the social norms underpinning this understanding of dignity are not inherently dignified. For example, by identifying opportunities to uphold standards of consumer society as a means of protecting dignity in food aid contexts, we gain insights into the societal landscape in which this assistance is provided, e.g. a consumer society (Andriessen et al. 2020). At the same time, it can be contended that the norms and values associated with a consumer society perpetuate the social exclusion faced by individuals living in poverty (Sen 1983; Bauman 2004). From this perspective, one could claim that maintaining consumer society standards within food aid settings contributes to the infringement of dignity among recipients within society as a whole. This highlights the multifaceted nature of the dignity of food aid recipients and emphasizes the significance of integrating a social dignity lens alongside a social justice framework. This integration is crucial for guiding transformative efforts towards food aid that empowers people facing poverty to lead dignified lives.

Furthermore, it is imperative to acknowledge that this emphasis on social norms has significantly shaped the narrative constructed within this paper concerning dignity in the context of food aid. Through the application of a social dignity framework, circumstances that empower recipients to uphold social standards are deemed as dignified. For instance, the presence of flowers on a dining table is regarded as a more dignified practice that aligns with certain expectations and conventions of social dining. Similarly, the establishment of a shop setting that grants recipients a certain degree of agency in selecting products is seen as dignifying, as it conforms to the norms prevalent in a consumer society. However, adopting an alternative perspective, such as a Foucauldian lens, permits a more critical evaluation of the same scenario’s. From a Foucauldian perspective one could argue that such arrangements impose disciplinary mechanism on recipients, compelling them to conform to specific norms, despite their awareness that the setting deviates from a customary social dining environment or regular supermarket contexts.

Finally, it is important to note that the query employed in this scoping review to identify literature has framed its findings. Limiting our search for literature to English language studies has influenced the scope in terms of geographical representation and the welfare states in which the food aid examined in the included papers is provided. This bias has probably amplified the dominant representation of studies conducted in the USA, Australia, UK and Canada. Overrepresentation of these countries has shaped our results, because these countries represent particular welfare systems framing responsibility for social welfare, i.e. individual versus collective responsibility (Aspalter 2010). This issue of responsibility marks public debates about poverty relief and consequently moralities performed at food aid settings. Exploring the specific ways in which different welfare systems affect the social dignity of individuals receiving food aid and examining how the prevailing portrayal of the USA, Australia, UK and Canada has shaped the narrative presented in this paper are intriguing areas warranting further investigation. Additionally, studies on alternative food services that do not explicitly address food (in)security may have been excluded by our search criteria. As a result, our search strategy may have constrained our ability to explore beyond the predominant focus on food banks/pantries found in the existing literature on food aid. Consequently, the narrative we have constructed regarding dignity may have been influenced by this selection.

Conclusion

Based on the 37 studies analysed in this scoping review through a social dignity lens, reflecting eight different forms of food aid in twelve Western high-income countries, we were able to construct five dimensions in food aid covering the aspects in the way food aid is provided as described to be important for the dignity of food aid receivers: (1) the access to food aid, (2) social interactions when receiving food aid, (3) the food, (4) the physical space, and (5) needs beyond food. Across these five dimensions, the insights of diverse situations of food aid as described in the selected literature allowed us to illustrate the entanglement between spaces, things, roles, and meanings in violations or protections of the dignity of food aid recipients. Hereby, this scoping review contributes to a complex, plural and situational understanding of dignity across different forms of food aid and national contexts, and indicates that there is no blueprint for a dignified approach of food aid.

A social dignity lens enabled us to bring together diverse signs of dignity violation and protection in various studies about third sector food aid, such as shame, gratitude, social exclusion, dependency and moral judgements. Combining these results, we identified aspects in the way food aid is provided as important for the dignity of recipients across diverse forms of food aid, such as eligibility criteria and appropriateness of the food. At the same time, the social dignity lens allowed us to illustrate how aspects in the provision of food aid are entangled in particular contexts of food aid, either reinforcing or challenging moralities and social hierarchies that impact the dignity of recipients.

While we took a first step in using a social dignity lens to develop a complex, plural and situational understanding of dignity in the context of food aid, it also provides directions for future research: (1) investigate in moralities, social hierarchies, and recipients’ autonomy and integrity at stake in situations of food aid, (2) identify mutual understandings of dignity across various food aid contexts, and (3) enhance the diversity and complexity of what dignity means in the context of food aid, e.g. in relation to race and gender. Hence, in order to use a social dignity lens to guide transformative efforts towards food aid that empowers people facing poverty to lead dignified life’s, it is essential to approach the prevailing social norms with a critical perspective, recognizing that social norms do not inherently embody dignity.

Whereas the aim of this paper was to foster plural and complex understandings of dignity across and in particular food aid contexts to move towards more dignified approaches of food aid, we don’t deny the significance of broader social structures influencing the dignity of people experiencing food poverty. Emotions like shame and gratitude in food aid settings are framed by internalized understandings of a low social status as an effect of dominant neoliberal discourses pursuing independency and self-responsibility (Goode 2006; Hackworth 2012; Garthwaite 2016; Williams et al. 2016). Debates about redesigning food aid in ways that value and promote people’s dignity should go hand in hand with changes in social policy and institutions that recognize citizens’ entitlement to food and fight discourses blaming individuals for situations of poverty. In other words, achieving a life of dignity for all necessitates governments’ acknowledgement of individuals’ right to food, entailing the need to address socio-economic and political factors that perpetuate poverty in high-income countries.

References

Allen, L., J. O’Connor, E. Amezdroz, P. Bucello, H. Mitchell, A. Thomas, K. Sue, B. Anthony, W. Liza, and C. Palermo. 2014. Impact of the social cafe meals program: a qualitative investigation. Australian Journal of Primary Health 20 (1): 79–84.

Andriessen, T., H. Van der Horst, and O. Morrow. 2020. “Customer is king”: Staging consumer culture in a food aid organization. Journal of Consumer Culture. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469540520935950.

Andriessen, T., O. Morrow, and H. Van der Horst. 2022. Murky moralities: Performing markets in a charitable food aid organization. Journal of Cultural Economy 15 (3): 293–309.

Arksey, H., and L. O’Malley. 2005. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 8 (1): 19–32.

Armstrong, D. 2000. A survey of community gardens in upstate New York: Implications for health promotion and community development. Health & Place 6 (4): 319–327.

Aspalter, C. 2010. Different worlds of welfare capitalism: Australia, the United States, the United Kingdom, Sweden, Germany, Italy, Hong Kong and Singapore. Australian National University Discussion Paper(80).

Bank, T. W. (2021). World bank country and lending groups. https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519

Bauman, Z. 2004. Work, consumerism and the new poor. UK: McGraw-Hill Education.

Bedore, M. 2018. “I was purchasing it; it wasn’t given to me”: Food project patronage and the geography of dignity work. The Geographical Journal 184 (3): 218–228.

Berardi, L., M.A. Rea, and L. Mook. 2021. Third sector accounting reform and integrated social accounting for Italian social economy organizations. Management Control. https://doi.org/10.3280/MACO2021-002-S1008.

Booth, S., A. Begley, B. Mackintosh, D.A. Kerr, J. Jancey, M. Caraher, W. Jill, and C.M. Pollard. 2018a. Gratitude, resignation and the desire for dignity: lived experience of food charity recipients and their recommendations for improvement, Perth. Western Australia. Public Health Nutrition 21 (15): 2831–2841.

Booth, S., C. Pollard, J. Coveney, and I. Goodwin-Smith. 2018b. ‘Sustainable’Rather than ‘subsistence’food assistance solutions to food insecurity: South Australian recipients’ perspectives on traditional and social enterprise models. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15 (10): 2086.

Bowe, M., J.R. Wakefield, B. Kellezi, N. McNamara, L. Harkin, and R. Jobling. 2019. ‘Sometimes, it’s not just about the food’: The social identity dynamics of foodbank helping transactions. European Journal of Social Psychology 49 (6): 1128–1143.

Bruce, J.S., M.M. De La Cruz, G. Moreno, and L.J. Chamberlain. 2017. Lunch at the library: Examination of a community-based approach to addressing summer food insecurity. Public Health Nutrition 20 (9): 1640–1649.

Chan, J., L. Pennisi, and C.A. Francis. 2016. Social-ecological refuges: Reconnecting in community gardens in Lincoln. Nebraska. Journal of Ethnobiology 36 (4): 842–860.

Clark, D. 2004. The raw and the rotten: Punk cuisine. Ethnology 43: 19–31.

Dagdeviren, H., M. Donoghue, and A. Wearmouth. 2019. When rhetoric does not translate to reality: Hardship, empowerment and the third sector in austerity localism. The Sociological Review 67 (1): 143–160.

Dailey, A.B., A. Hess, C. Horton, E. Constantian, S. Monani, B. Wargo, and K. Gaskin. 2015. Healthy options: a community-based program to address food insecurity. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community 43 (2): 83–94.

Dayle, J.B., L. McIntyre, and K.D. Raine-Travers. 2000. The dragnet of children’s feeding programs in Atlantic Canada. Social Science & Medicine 51 (12): 1783–1793.

Diekmann, L.O., L.C. Gray, and G.A. Baker. 2020. Growing ‘good food’: Urban gardens, culturally acceptable produce and food security. Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems 35 (2): 169–181.

Douglas, F., J. Sapko, K. Kiezebrink, and J. Kyle. 2015. Resourcefulness, desperation, shame, gratitude and powerlessness: Common themes emerging from a study of food bank use in Northeast Scotland. AIMS Public Health 2 (3): 297.

Edwards, F. 2021. Overcoming the social stigma of consuming food waste by dining at the Open Table. Agriculture and Human Values 38 (2): 397–409.

Engler-Stringer, R., and S. Berenbaum. 2007. Exploring food security with collective kitchens participants in three Canadian cities. Qualitative Health Research 17 (1): 75–84.

Fong, K., R.A. Wright, and C. Wimer. 2016. The cost of free assistance: Why low-income individuals do not access food pantries. J. Soc. & Soc. Welfare 43: 71.

Galli, F., S. Arcuri, F. Bartolini, J. Vervoort, and G. Brunori. 2016. Exploring scenario guided pathways for food assistance in Tuscany. Bio-Based and Applied Economics 5 (3): 237–266.

Garthwaite, K. 2016. Hunger pains: Life inside foodbank Britain. Bristol: Policy Press.

Gómez Garrido, M., M.A. Carbonero Gamundí, and A. Viladrich. 2019. The role of grassroots food banks in building political solidarity with vulnerable people. European Societies 21 (5): 753–773.

Goode, J. 2006. Faith-based organizations in Philadelphia: Neoliberal ideology and the decline of political activism. Urban Anthropology and Studies of Cultural Systems and World Economic Development 21: 203–236.

Haapanen, S. 2017. The Finnish Breadline: An enforcer of social class and right to space? Nordia Geographical Publications 46 (3): 23–26.

Hackworth, J. 2012. Faith based: Religious neoliberalism and the politics of welfare in the United States. Athens: University of Georgia Press.

Hebinck, A., F. Galli, S. Arcuri, B. Carroll, D. O’connor, and H. Oostindie. 2018. Capturing change in European food assistance practices: A transformative social innovation perspective. Local Environment 23 (4): 398–413.

Herrington, A., and T.L. Mix. 2021. Invisible and insecure in rural America: Cultivating dignity in local food security initiatives. Sustainability 13 (6): 3109.

Jacobson, N. 2007. Dignity and health: A review. Social Science & Medicine 64 (2): 292–302.

Jacobson, N. 2009. A taxonomy of dignity: A grounded theory study. BMC International Health and Human Rights 9 (1): 1–9.

Jacobson, N. 2012. Dignity and health. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press.

Killmister, S. 2017. Dignity: Personal, social, human. Philosophical Studies 174 (8): 2063–2082.

Kolavalli, C. 2019. Whiteness and food charity: Experiences of food insecure African-American Kansas city residents navigating nutrition education programs. Human Organization 78 (2): 99–109.

Kravva, V. 2014. Politicizing hospitality: The emergency food assistance landscape in Thessaloniki. Hospitality & Society 4 (3): 249–274.

Lambie-Mumford, H., and E. Dowler. 2015. Hunger, food charity and social policy–challenges faced by the emerging evidence base. Social Policy and Society 14 (3): 497–506.

Leget, C. 2013. Analyzing dignity: A perspective from the ethics of care. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy 16 (4): 945–952.

Levkoe, C., and S. Wakefield. 2011. The community food centre: Creating space for a just, sustainable, and healthy food system. Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development 2 (1): 249–268.

Lindberg, R., J. McCartan, A. Stone, A. Gale, A. Mika, M. Nguyen, and S. Kleve. 2019. The impact of social enterprise on food insecurity–An Australian case study. Health & Social Care in the Community 27 (4): e355–e366.

Loopstra, R. 2018. Interventions to address household food insecurity in high-income countries. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 77 (3): 270–281.

May, J., A. Williams, P. Cloke, and L. Cherry. 2019. Welfare convergence, bureaucracy, and moral distancing at the food bank. Antipode 51 (4): 1251–1275.

May, J., A. Williams, P. Cloke, and L. Cherry. 2020. Food banks and the production of scarcity. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 45 (1): 208–222.

McKay, F.H., K. Lippi, M. Dunn, B.C. Haines, and R. Lindberg. 2018. Food-based social enterprises and asylum seekers: The food justice truck. Nutrients 10 (6): 756.

McNaughton, D., G. Middleton, K. Mehta, and S. Booth. 2021. Food charity, shame/ing and the enactment of worth. Medical Anthropology 40 (1): 98–109.

Meiklejohn, S.J., L. Barbour, and C.E. Palermo. 2017. An impact evaluation of the FoodMate programme: Perspectives of homeless young people and staff. Health Education Journal 76 (7): 829–841.

Meyer, M.J. 2001. Dignity as a modern virtue. In The concept of human dignity in human rights discourse, 195–207. Leiden: Brill Nijhoff.

Middleton, G., K. Mehta, D. McNaughton, and S. Booth. 2018. The experiences and perceptions of food banks amongst users in high-income countries: An international scoping review. Appetite 120: 698–708.

Möller, C. 2021. Discipline and Feed: Food Banks, Pastoral Power, and the Medicalisation of Poverty in the UK. Sociological Research Online 26 (4): 853–870.

Munn, Z., M.D. Peters, C. Stern, C. Tufanaru, A. McArthur, and E. Aromataris. 2018. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology 18 (1): 1–7.

Nordenfelt, L. 2003. Dignity and the care of the elderly. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy 6 (2): 103–110.

Nordenfelt, L. 2004. The varieties of dignity. Health Care Analysis 12 (2): 69–81.

Organ, J., H. Castleden, C. Furgal, T. Sheldon, and C. Hart. 2014. Contemporary programs in support of traditional ways: Inuit perspectives on community freezers as a mechanism to alleviate pressures of wild food access in Nain, Nunatsiavut. Health & Place 30: 251–259.

Parson, S. 2014. Breaking bread, sharing soup, and smashing the state: Food Not Bombs and anarchist critiques of the neoliberal charity state. Theory in Action 7 (4): 33.

Pols, J., B. Pasveer, and D. Willems. 2018. The particularity of dignity: Relational engagement in care at the end of life. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy 21 (1): 89–100.

Power, E. 2011. Canadian food banks: Obscuring the reality of hunger and poverty. Food Ethics 6 (4): 18–20.

Power, M. 2022. Hunger, whiteness and religion in Neoliberal Britain: An inequality of power. Bristol: Policy Press.

Power, M., N. Small, B. Doherty, B. Stewart-Knox, and K.E. Pickett. 2017. “Bringing heaven down to earth”: The purpose and place of religion in UK food aid. Social Enterprise Journal 13 (3): 251–267.

Remley, D.T., A.C. Zubieta, M.C. Lambea, H.M. Quinonez, and C. Taylor. 2010. Spanish-and English-speaking client perceptions of choice food pantries. Journal of Hunger & Environmental Nutrition 5 (1): 120–128.

Riches, G., and T. Silvasti. 2014. First world hunger revisited: Food charity or the right to food? Cham: Springer.

Rombach, M., V. Bitsch, E. Kang, and F. Ricchieri. 2018. Comparing German and Italian food banks: Actors’ knowledge on food insecurity and their perception of the interaction with food bank users. British Food Journal 120: 2425.

Rowland, B., K. Mayes, B. Faitak, R.M. Stephens, C.R. Long, and P.A. McElfish. 2018. Improving health while alleviating hunger: Best practices of a successful hunger relief organization. Current Developments in Nutrition 2 (9): nzy057.

Salamon, L.M., and H.K. Anheier. 1997. The third world’s third sector in comparative perspective. Princeton: Citeseer.

Salonen, A.S. 2016. Locating religion in the context of charitable food assistance: An ethnographic study of food banks in a Finnish city. Journal of Contemporary Religion 31 (1): 35–50.

Sen, A. 1983. Poor, relatively speaking. Oxford Economic Papers 35 (2): 153–169.

Shamasunder, B., R. Mason, L. Ippoliti, and L. Robledo. 2015. Growing together: Poverty alleviation, community building, and environmental justice through home gardens in Pacoima, Los Angeles. Environmental Justice 8 (3): 72–77.

Shinwell, J., E. Finlay, C. Allen, and M.A. Defeyter. 2021. Holiday club programmes in Northern Ireland: The voices of children and young people. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18 (3): 1337.