Abstract

The human labor and animal inputs required to manufacture meat products are kept physically and symbolically distanced from the consumer. Recently however, meatpacking plants received significant news media attention when they emerged as hotpots for COVID-19 — threatening workers’ health, requiring plants to slow production, and forcing farmers to euthanize livestock. In light of these disruptions, this research asks: how did news media frame the impact of COVID-19 on the meat industry, and to what extent is a process of defetishization observed? Examining a sample of 230 news articles from coverage of US meatpacking plants and COVID-19 in 2020, I find that news media largely attributes the cause for the spread of COVID-19 in meatpacking plants to the history of exploitative working conditions and business practices of the meat industry. By contrast, the solutions offered to address these problems aim at alleviating the immediate obstacles posed by the pandemic and returning to, rather than challenging, the status quo. These short-run solutions for complex issues demonstrate the constraints in imagining alternatives to a problem rooted in capitalism. Furthermore, my analysis shows that animals are only made visible in the production process when their bodies become a waste product.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Across the US and Canada, meatpacking plants emerged as ‘hotspots’ for the COVID-19 pandemic and became sites of political contestation (Hobbs 2021). The COVID-19 crisis brought media attention and public awareness to meat production as it became apparent that the conditions of meatpacking plants allowed the virus to spread rapidly, impacting the health of a mostly racialized and low-paid workforce along with the communities that reside near these plants (Taylor et al. 2020). With their labor supply under threat, some plants were forced to either halt or limit production by adopting various precautionary measures (Hobbs 2021). Consequently, some farmers were forced to euthanize their livestock due to overcrowding and financial loss (O’Sullivan 2020). This led to widespread concerns about potential disruptions to the food supply chain and increases in meat prices (Hobbs 2021).

The impact of COVID-19 on the meat industry has thus presented a discursive opportunity for various groups to mobilize frames through news media. One of the main functions and effects of news media is to influence and mirror how the public views meat production and its problems(Oleschuk 2020; Gamson and Modigliani 1989). The way a crisis is presented affects the public’s perception of the issue and indicates possible solutions (Oleschuk 2020; Benford and Snow 2000). By reaching a large and diverse audience, news media can "influence public opinion, policy decisions, and collective action", making it an instructive site for examining the transformational potential of COVID-19 (Oleschuk 2020, p. 3; Snow and Benford 1988).

Crucially, COVID-19 has proven to be a magnifier for existing societal inequalities (Czymara et al. 2021; Kim and Bostwick 2020; Patel et al. 2020), and its impacts on meat production are no exception (Taylor et al. 2020). The outbreaks in meat processing plants have highlighted the interrelated dangers posed to humans and animals in meat production. But the recent crisis is only one of many controversies the meat industry has faced. For some time, activists and scientists alerted the public to the dangers associated with meat production, including public health risks, environmental impacts, animal welfare, and dangerous labor conditions (Bateman et al. 2019). Despite awareness of the problems associated with meat products, scholars have emphasized that meat still retains its “everyday legitimacy amongst consumers” — a legitimacy that is linked to multiple factors, including the ways news media presents the issues of meat to consumers (Chiles 2017, p. 791; Bateman et al. 2019).

For some political ecologists and critical animal scholars (Chiles 2017; Fitzgerald 2015; Gunderson 2011), the taken-for-granted nature of meat is associated with the development of industrial capitalism, whereby meat has become both physically and symbolically distanced from labor and animals necessary for its production. I draw here on the Marxist concept of commodity fetishism, which suggests that the commodification of meat — the raising of livestock primarily for exchange rather than for consumption — has separated the human and animal suffering involved in meat’s production from the delicious product that is served at the dinner table (Bulliet 2005; Gunderson 2011; Kalof 2007; Longo and Malone 2006). In other words, meat appears divorced from the social and ecological relations embedded in its production, and the representation of meat in news media maintains this estrangement (Chiles 2017).

This paper evaluates the extent to which news media’s coverage of COVID-19 outbreaks in US meatpacking plants has challenged this reified portrayal of meat production and opened up new opportunities for political action. I examine this by drawing on and critically interrogating the concept of defetishization — a process that is said to bring the human, labor, and animal inputs from behind the curtain of commodification and put them into the public view. Through this investigation, I highlight the role of capitalism and news media in maintaining and challenging dominant ideologies surrounding meat. Empirically, this paper documents how news media has framed the problems and possibilities that arise from the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the meat industry. Analytically, this paper extends an ongoing theoretical debate concerning the possibilities and limitations of defetishizing the relations of meat production by observing the response to a crisis that can potentially challenge the ideology of modern-industrial livestock production. To capture these analytical and empirical concerns, this paper is motivated by the following question: how did news media frame the impact of COVID-19 on the meat industry, and to what extent is a process of defetishization observed? Specifically, this paper seeks to understand crises as a potential opportunity for defetishization and explore the ideological structures constraining this possibility.

The meatpacking industry: historical and contemporary overview

The COVID-19 pandemic has spread unevenly, with some communities and industries facing a disproportionate burden (Taylor et al. 2020). Specific factors in the meatpacking industry have made plants especially vulnerable to the spread of respiratory viruses (Taylor et al. 2020). These factors include working for long hours in close contact with others, performing strenuous tasks that make wearing masks challenging, sharing transportation with co-workers, labor practices that incentivize workers to continue working while sick, and the consolidation of the industry with high degrees of power over labor (Taylor et al. 2020). While the spread of COVID-19 in meatpacking plants has ignited criticism against working conditions in plants, this concern is hardly new, and the industry’s reputation for harsh working conditions is longstanding. The exploitative conditions of the slaughterhouse have been well known since Upton Sinclair (1906) depicted the plight of immigrant workers in Chicago’s Union Stockyard in the novel, The Jungle. This notoriety has endured, and meatpacking has consistently been viewed as one of the most dangerous of any jobs in North America — with rates of illness and injury frequently ranked among the highest in any industry (Broadway 2007; Broadway and Stull 2008; Fitzgerald 2010). In addition to the prevalence of physical risks in meatpacking plants, there is also a significant psychological toll on workers as they “watch — and are implicated in — the gruesome deaths of thousands of animals every week” (Dillard 2008, p. 5). Some scholars (Dillard 2008; MacNair 2002) have even suggested slaughterhouse workers may experience Perpetration Induced Traumatic Stress (PITS) — a form of PSTD found in combat veterans, law enforcement, and executioners — through their role in the killing and disassembly of animals.

The recent history of meat production in the US is characterized by the implementation and development of industrial technologies, a growing concentration and consolidation of key industry players, and a decline in union power (MacLachlan 2001). Scholars have also noted a dramatic geographic and demographic shift in meat production over the 20th century as meatpacking plants moved from urban areas, such as Chicago, New York, and Toronto, to rural areas to be closer to the supply of cattle (Broadway 2007; Fitzgerald 2015). The limited supply of labor in these towns, alongside the high turnover rates of meat processing plants, has necessitated an increasing reliance on immigrant labor (Broadway 2007). The changing demographics of the workplacehas made migrant workers more vulnerable to exploitation — particularly undocumented workers who may be hesitant about reporting illnesses or injuries to their employers (Fitzgerald 2015). Additionally, the changing demographics of predominantly white rural towns hosting new meatpacking plants have fueled xenophobic anxieties about racialized workers (Gouveia and Juska 2002).

Notably, this geographic shift has been associated with a larger trend of physical and social separation between consumers and the laborers who slaughter and process animals (Bulliet 2005; Gouveia and Juska 2002; Pachirat 2011). Consumers in a postdomestic society —characterized by a separation from animals used for production, while still forming close bonds with companion animals — rarely have to think about or face the realities of meat production (Bulliet 2005). These economic and social relations perpetuate a system that slaughters an increasing number of animals while simultaneously providing a diminishing quality of life for livestock, all while remaining out of the hearts and minds of consumers (Fitzgerald 2010; Pachirat 2011).

COVID-19 and meatpacking plants

With the most reported deaths of COVID-19 in the world, the full impact of the pandemic in the United States remains to be seen. Early estimates suggest that the livestock industry experienced substantial financial loss and contributed to a staggeringly high transmission rate of COVID-19 among workers and their broader communities (Taylor et al. 2020; Hobbs 2021). The loss of production capacity due to the closure of plants reached as high as 43% for beef production, and pork producers removed 10 million hogs from the supply chain due to the impact of the pandemic (Hashem et al. 2020). Meanwhile, Taylor et al. (2020, p. 31707) found that counties with a slaughterhouse were associated with “four to six additional COVID-19 cases per thousand”, indicating an increase of 51 to 75% in the baseline transmission rate in the US at the time. At the height of these outbreaks, it is estimated that livestock plants were associated with “6 to 8% of all US cases” and “3 to 4% of all US deaths” — with a majority of those cases involving community members and family members not working at meatpacking plants (Taylor et al. 2020, p. 31707).

In the midst of this burgeoning crisis, policymakers reacted quickly to protect the financial interests of the meat industry. On April 24, 2020, former US President Donald Trump signed an executive order requiring meat and poultry production to continue operations regardless of state orders or the guidance of other governing bodies (White House 2020). This order declared meatpacking plants to be considered “critical infrastructure” and must therefore continue operations “to ensure a continued supply of protein for Americans” (White House 2020). An investigative report by Pro Publica has suggested that the meat industry had a significant influence on the drafting of this order, as evidenced by emails attained from the Freedom of Information Act (Grabell and Yeung 2020). Additionally, the CDC (2021) released a set of interim guidelines that include — as a “last resort” — the allowance of workers “to continue work following potential exposure to COVID-19, provided they remain asymptomatic, have not had a positive test result for COVID-19, and additional precautions are implemented to protect them and the community.” In sum, the US federal government demonstrated a firm commitment to protect the interests of the meat industry rather than protect the health of workers — raising questions about whether COVID-19 has the potential to challenge the status quo of meat production or merely reproduce it.

Commodification, reification, and objectification

Despite the numerous deep-seated problems with the meat industry, specifically meatpacking plants, these exploitative practices escape everyday scrutiny (Chiles 2017; Bateman et al. 2019). Critical social theorists point to the drive for capitalist accumulation to explain how the exploitation of both human and nonhuman labor remains disconnected from the consumers of meat products. The commodification of meat justifies the exploitation of human and nonhuman life for profit by masking the social and ecological relations through which meat products are created.Footnote 1 The logic of capitalism drives animal agriculture to prioritize profit (i.e., exchange value) over satisfying human needs (i.e., use value) (Gunderson 2011). The capitalist mode of production obscures the origin of a product as a social relation and severs the connection between a commodity, its physical properties, and its material relations (Marx 1867; Eagleton 1991). As a result, commodity fetishism reifies capitalist relations — making capitalism appear natural rather than a human product that can therefore be altered (Gunderson 2011; Lukács 1923). Significantly, as Lukács (1923) emphasizes, commodity fetishism reduces the labor-power of workers to mere objects, rather than subjects, that are to be exchanged on the market.

Some critical scholars (Adams 1990; Horkheimer and Adorno 1944; Kalof 2007; Longo and Malone 2006) have extended this notion to suggest that commodity fetishism not only reduces people to things, but also objectifies nonhuman nature. As Longo and Malone (2006, p. 115) assert, “commodification drives a wedge between human and nonhuman animals and, further, justifies the mass exploitation of all living beings.” In this instrumentalized view of nature, animals and humans alike are perceived as objects that can be manipulated and expended for humans’ desired ends (Longo and Malone 2006; Horkheimer and Adorno 1944). For Carol Adams (1990), this objectification — of both workers and animals — is a necessary condition for the production and consumption of meat. She employs the concept of the “absent referent” to describe the separation of “the meat eater from the animal and the animal from the end product” (Adams 1990, p. 13). For Adams (1990), we often talk about meat without reference to animals, further mystifying the commodity. Consequently, slaughterhouse workers face a “double annihilation of the self” through both the objectification of their labor and their acceptance of the absence of the animal from meat production as they must view the “living, breathing animal” as meat to carry out their work (Adams 1990, p. 80).

While these ideological characteristics are essential for understanding contemporary discourses around the meat industry, it remains unanswered whether the crisis in meatpacking plants across North America can lift the veil of the commodity form and bring awareness of exploitative practices to the minds of consumers, or whether such an outcome is even possible. To what extent can a crisis like what has emerged in slaughterhouses challenge or even alter these ideological structures I have outlined above?

The defetishizing question

The notion of defetishization has gained attention in fair trade and ethical consumption literature and several scholars (Allen and Kovach 2000; Castree 2001; Gunderson 2014) have explored the possibility of demystifying the ideological structures of commodity fetishism from various lenses. Gunderson (2014) attributes Allen and Kovach (2000) with coining the term defetishization to suggest that alternative markets, such as organic food, can offer consumers more transparency about the production of a commodity and therefore reduce the disconnect between consumption and production. However, this understanding has justifiably been the subject of critique (Castree 2001). Gunderson (2014) captures the essence of these critiques by arguing that the implication of the defetishization thesis — the possibility of limiting capital’s excess through critiques of commodities — has only served to conceal capitalist exploitation and potentially adds another layer of commodity fetishism.

These concerns about the problems with the defetishization thesis have also received empirical support. In the context of meat production, Cairns et al. (2015) examine an advertising campaign implemented by the Manitoba provincial government, which attempted to ‘put a face’ to pork producers in response to concerns about the environmental impacts of pork production. As Cairns et al. (2015, p. 1198) expose, this campaign presented a misleading image of pork production as “small-scale and family oriented”. This example demonstrates how by replacing the obscured image of production with another, one-sided representation, the contradictions in the relations of production end up only further concealed (Johnston, et al.2009). Moreover, researchers have found that meat products continue to be consumed at high rates despite increased concern about the treatment of animals in slaughterhouses (Bastian et al. 2012; Oleschuk et al. 2019). This meat paradox suggests that consumers in North America and Europe are largely aware of, and concerned with, the problems of meat, but rates of vegetarianism remain low (Bastian et al. 2012; Oleschuk et al. 2019). Similarly, consumer studies have shown that an awareness of the problems of consumer goods often does not translate to changes in consumer behavior — a phenomenon known as the attitude-behavior gap (Vermeir and Verbeke 2006).

These critiques and limitations raise the question of whether defetishization is still a worthwhile concept for understanding the processes that critique and challenge a commodity. If consumer awareness does not result in behavioral changes, then what can this notion of defetishization offer? Does defetishization merely add another layer of commodity fetishism? I seek to navigate this debate by taking the shortcomings of the defetishization thesis seriously, while also considering what potentialities and possibilities could emerge from a defetishizing critique. To do so, I start from the premise that ideologies are not totalizing — that there is a tension “between concrete social formations and their ideologies” (Antonio 1981, p. 334, emphasis added). The notion of immanent critique, which Antonio (1981) argues lies at the core of critical theory, suggests that it is possible to make ideological critiques from outside the standpoint of an ideology. With this consideration, how can we recover the theoretical possibility of defetishization?

Johnston et al. (2009), through examining the appropriation of food democracy discourse by corporate organic producers, propose an alternative understanding of defetishization that goes beyond merely revealing the ‘real’ origins of a commodity. Instead, it is suggested that defetishization critiques can potentially open up social and cultural practices to political contestation and transformation (Johnston et al. 2009). For Johnston et al. (2009, p. 526), the aim of defetishization “is not to posit another pre-given, essentialized understanding of the nature of social reality, but rather to open the constitution of that social reality up to question.” In other words, defetishizing is about demonstrating new political possibilities and is not simply about revealing the hidden reality beyond the commodity form (Johnston et al. 2009). This includes challenging concentrations of corporate power and developing “new citizen-based modes of engagement” (Johnston et al. 2009, p. 526). This understanding offers a starting point for salvaging the possibility of challenging the reified relations of capitalist production; what remains is finding instances that meet this criterion for defetishization.

In their classic paper, Reification and Sociological Critique of Consciousness, Berger and Pullberg (1965) not only accept the possibility of de-reification, but also attempt to identify specific empirical instances in human history. According to Berger and Pullberg (1965, p. 209), history offers numerous examples of “natural or manmade catastrophes” disintegrating the social structures of a particular world “including its hitherto well-functioning reifying apparatus, bringing forth doubt and skepticism concerning everything that had previously been taken for granted.” It is in these moments that we can recognize structures such as capitalist social formations are human-produced, and thus open to change (Berger and Pullberg 1965). Crises present opportunities for defetishizing/de-reifying critique by disenchanting the taken-for-granted world — not by revealing the true origins of commodity relations, but by opening up the possibility for social transformations. One could expect the COVID-19 crisis to have the potential to be such a moment, which provides an impetus for empirical analysis of news media to observe the extent to which, and how, defetishization is or is not happening.

Framing of meat in news media

Discourse analysis of news media continues to be an indispensable tool for examining the construction of social problems, harms, and risks. Even as the public consults various information sources, newspapers still play a significant role in shaping social issues and are valuable for accessing public discourses (Chiles 2017). As several scholars have demonstrated (Chiles 2017; Kojola 2017; Leroy et al. 2018; Mccombs and Reynolds 2009), mass media reproduces, circulates, and draws on the dominant ideologies of a given society as it frames public agendas. As Chiles (2017, p. 793) identifies, a “suppressive synergy” occurs between the “meat industry, mass media, and consumers’ habits” which prevents the public from recognizing the deep-seated, structural problems associated with meat. Consequently, most news media reporting on meat presents problems as inevitable facts that we must accept rather than overcome (Chiles 2017). The problems of meat only receive significant media attention when a “headline-grabbing crises” emerges, but this coverage fades once the immediate threat is gone (Chiles 2017, p. 801).

Framing theory is a particularly useful tool to understand how news media presents public debates about social problems. According to frame theory, media discourse can be seen as a “symbolic contest” of competing sponsors of different frames (Gamson and Modigliani 1989, p. 2). These frames highlight specific aspects of an issue and presents them as important to suggest a way of understanding or addressing a social problem (Kojola 2017). From this literature, Benford and Snow’s (2000) framework is advantageous because it distinguishes between three core framing tasks that are used to foster consensus and action: (1) Diagnostic frames are used to define and explain the problem, usually in relation to causality or blame; (2) Prognostic frames present a solution to the problem and outline the steps needed to achieve it; and (3) Motivational frames communicate reasons to act toward resolving a social issue (Snow and Benford 1988). Outbreaks in meatpacking plants present a discursive opportunity for different groups (unions, workers, corporations, political actors, the state, etc.) to assert their understanding of the crisis as well as articulate and motivate solutions that align with their interests.

Importantly, Benford and Snow (2000) assert that the way a problem is articulated restricts what solutions are considered possible and limits the strategies that are proposed. In fact, recent work has demonstrated that fruitful critical analysis can arise when examining the incongruency between prognostic and diagnostic frames (Oleschuk 2020; Huddart Kennedy et al. 2018). Huddart Kennedy et al. (2018) make a generative contribution to framing theory by drawing on Perrin’s (2006, p. 2) concept of democratic imagination, which suggests that “what you decide to do (or not do) is based largely on what you can imagine doing: what is possible, important, right, and feasible.” Huddart Kennedy et al. (2018) use the distinction between diagnostic and prognostic frames to characterize a political culture as thick or thin based on the range and breadth of solutions, outcomes, and actions available in the public discourse. A thick democratic imagination emerges when the public is able to engage in discussion about a social problem, and propose various strategies and solutions to address it (Huddart Kennedy et al. 2018). On the other hand, a thin democratic imagination restricts the scope of debate and limits the range of possible actions that can be taken (Huddart Kennedy et al. 2018). This engagement with framing theory offers a nuanced approach to evaluating a given discourse by considering that how we talk about the possibilities for action and social change shapes how “a group or society will respond to challenges, crises, and opportunities” (Huddart Kennedy et al. 2018, p. 4). There is considerable overlap between a thick democratic imagination and defetishization as conceptualized by Johnston et al. (2009), with both notions emphasizing a critical understanding of a problem that allows for new possibilities for political action, making this a particularly illuminating framework for my analysis.

Following Huddart Kennedy et al. (2018), I apply Benford and Snow’s (2000) framework of diagnostic, prognostic, and motivational frames in combination with Perrin’s (2006) conception of the democratic imagination to structure my analysis of North American news media in 2020. This framework is well suited to my inquiry because it allows for a comparison between the frames that identify and assign blame to the problem from those that offer determinate solutions (Huddart Kennedy et al. 2018). This analytical comparison allows for an evaluation of the extent to which longstanding structural issues in the meat industry are identified as factors related to the crisis in meatpacking plants, but also, the extent to which the solutions point to a process of defetishization by opening the composition of that social reality to question and proposing new political possibilities. In other words, my analysis will account for how news media discuss and frame (1) the range of topics mobilized to articulate the problem, (2) the extent and breadth of possible actions or plans of attack, and (3) the rationale for engaging in action. My analysis seeks to answer how news media can question the reality of the commodity form, to what extent they do so, and to what extent new political possibilities emerge. Finally, through an analysis of motivational frames, I can examine the stakes that are deemed important by news media to incentivize action. Understanding what is to be considered at risk if collective action is not taken reveals what a given ideology regards as important. Through this analysis, I seek to intervene in the debate over the theoretical potential of defetishizing meat production by paying attention to the willingness and ability to imagine and propose alternatives to the status quo.

Methodology

Data

Using ProQuest’s database of US News streams, I searched for news articles including the terms “Meatpacking,” “Slaughterhouse,” “Meat Processing,” or “Meat Packaging,” and “COVID” or “Coronavirus” which produced 2,655 results. I used systematic sampling, selecting every 10th article published between April 2020 and August 2020 on meat and COVID-19.Footnote 2 After deleting duplicates and articles that did not discuss meatpacking and COVID-19, I arrived at a final sample of 230 articles. I used this sampling technique to generate an unbiased sample of the larger corpus of articles that was still small enough to be subject to in-depth framing analysis but large enough to capture the diversity of frames and to identify patterns in rhetoric and themes for identifying the frames. This sampling technique had the advantage of producing a diverse set of article types including editorials, news articles, and news releases by politicians, unions, corporations, and various organizations. Furthermore, my sample includes a range of newspapers, including rural sources that are geographically close to the sites of meatpacking plants. From this sample, 81 articles are from generally circulated national media sources, and 209 are local. Among the local articles, 21 are from rural areas with populations of less than 10,000.Footnote 3

Methods

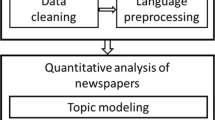

I began my analysis with an inductive coding of my data to produce several themes related to the various agents and institutions involved, the problems and conflicts identified, and the solutions proposed and undertaken. My coding was sensitive to the “condensing symbols” of media frames as Gamson and Modigliani (1989, p. 3) outline. This includes paying attention to framing devices such as the “metaphors, catchphrases, visual images [and] moral appeals” contained within a particular media package (Gamson and Modigliani 1989, p. 2). Additionally, I took note of the various social actors represented through media reporting by considering who is quoted and which voices are excluded (Kojola 2017). This process led to identifying the various diagnostic, prognostic, and motivational frames — which emerged from my initial inductive coding. Six frames emerged from this process, with two frames identified per framing task.

To supplement this frame analysis, a content analysis was used to assess the salience of the frames. To provide a count of the frequency of each frame, I re-examined my data, assigning each article by identifying the frames contained within them. These frames are not mutually distinct, and an article can contain more than one of the core framing tasks (diagnostic, prognostic, motivational) and more than one subframe in each article, as was often the case (see Table 2).Footnote 4

Analysis

My analysis is organized around the three core framing tasks identified by Benford and Snow (2000). With each of these frames, I examine if and how the COVID-19 crisis has allowed news media to demystify the taken-for-granted meat industry. In this analysis, I focus on the incongruence between and within frames, revealing the actions available in the public discourse to cope with outbreaks in the meat industry.

My findings indicate two diagnostic frames attentive to either the structural problems associated with the meat industry or the workers as a cause for the spread of the virus; two prognostics frames that concentrate on relieving the immediate problems the crisis poses to the meat industry by either slowing down production or protecting the supply of meat; and, finally, three motivational frames that emphasize either the importance of workers or the food supply chain. Through my analysis of diagnostic frames, I find evidence of a thick democratic imagination that has enabled complex and multifaceted critiques and challenges of the meat industry. The variety of issues articulated to diagnose the problem illustrates how historically problematic characteristics of the industry (MacLachlan 2001) became scrutinized during the crisis. Still, the possibility of defetishization — conceived of as a contestation of social relations and the consideration of the possibility of social transformations (Johnston et al. 2009) — is limited. The constrained ability to imagine solutions that potentially challenge the status quo — as is shown in the two prognostic framings, which focus on alleviating the immediate problems posed by the crisis — reveals a thin democratic imagination and the limits of a defetishizing critique in this instance.

Diagnostic framing

Diagnostic framings articulate the causes related to how meatpacking plants became hotspots for the spread of COVID-19. I identified two diagnostic frames that emerged from my data: (1) ‘exploitative industry’; and (2) ‘irresponsible workers’. The first frame recognizes the meat industry’s (exploitative) practices as responsible for the spread of COVID-19 among meatpacking workers and the resultant supply chain issues. What is noteworthy about this finding is that research on environmental disasters typically finds that hazards are framed as “mono-causal” instead of “involving long and complex causal networks” (Hannigan 2014, p. 108). Similarly, Chiles (2017) finds that systemic issues are largely ignored in the mass media’s coverage of the meat industry. By contrast, this study shows that the diagnostic framing of meatpacking and COVID-19 works to bring attention to structural issues in the meat industry, with specific awareness to its long history of problems — especially as they relate to labor conditions. By contrast, the second diagnostic frame, ‘irresponsible workers’, identifies the lifestyles and behaviors of meatpacking plant workers as responsible for the spread of the virus among plants and is chiefly directed at racialized workers. Instead of pointing to structural problems in the meat industry, the ‘irresponsible workers’ frame is directed toward the individual. In this sense, workers are made visible in the production of the commodity, and yet, they are presented as a contributing factor to the problems in meatpacking plants — instead of understanding the risks workers face as a problem. Analyzing both diagnostic frames can help us understand how the crisis might shed light on previous historical problems linked to the meat industry’s exploitative practices.

Exploitative industry

The first frame is found in 52% of articles (Table 2) and identifies the meat industry’s (exploitative) practices as primarily responsible for the spread of COVID-19 among meatpacking workers and the resultant supply chain issues. A variety of structural issues associated with the meat industry are linked to the ‘exploitative industry frame’, including the physical conditions of meatpacking plants, plants’ health and safety practices, the economic situation of workers, the consolidation of the meatpacking industry, automation, and the fragility of the food supply chain. The physical conditions of plants, particularly the proximity of workers on the line, are discussed as a core contributor to the spread of COVID-19 in plants. As described in the Green Bay Press-Gazette:

Employees in the plants, many of them Latino, work elbow-to-elbow as they perspire and breathe heavily, Minikel said. Many gathered in break and lunchrooms at one time, making it difficult to socially distance. JBS also encouraged people to continue to work during the pandemic with free T-shirts, ground beef and toilet paper, according to a text message sent to an employee in April (BeMiller 2020).

As illustrated in this quote, racialized workers in particular are recognized as being disproportionately impacted by these structural issues, given the meat industry’s reliance on this population for labor. The Des Moines Register quotes Forward Latino National Vice President Joe Henry: “They’re just trying to make as much profit as quickly as they can with their predominantly black and brown workforce in the factory” (Jett 2020). Invoking Sinclair’s (1906) sympathetic portrayal of migrant laborers in The Jungle, this frame positions workers within the broader social, historical, and economic context in which meat is produced.

Highlighting further systemic issues in modern meat production — news media brings attention to the consolidation of the meat industry and the consequences that a high concentration of large corporations has for the health of the food supply chain. One article written for Bloomberg (and widely republished) recognizes the consolidation of the meat industry: “This is 100% a symptom of consolidation,“…"We don’t have a crisis of supply right now. We have a crisis in processing. And the virus is exposing the profound fragility that comes with this kind of consolidation” (Skerritt 2020). This article adopts a framing that highlights the de-reifying potential of the pandemic by exposing the fragility that consolidation brings to the supply of meat. Furthermore, this article explicitly names and attributes blame to corporations such as Tyson, JBS, Cargill, and Smithfield. Implied in this framing is that the concentration of production power was intentional and orchestrated by nameable organizations.

Finally, the fetishized character of meat is recognized as a structural problem. This is only recognized in two articles, yet it is worth mentioning that it is included because of its novelty. The Christian Science Monitor cites a worker who tested positive for COVID-19:

… He hopes Americans shopping in the supermarket are becoming more aware of the people who bring them the bacon, so to speak –from the farmers to the truck drivers to the processing plant workers. “We’re behind the scenes until there’s a pandemic or something like this that comes along, and it’s put out there that, ‘Hey, this is what’s being done for you to go in there and pick it off the shelf and put it in your oven, or your skillet,’” he says. “Until this came along, I don’t think the average person even thought about what all is done for the meat to get out there to them. (Bryant 2020)

In this quote, the fetishistic character of meat is identified as a problem. This worker hopes that the COVID-19 crisis can challenge this reified view of meat by reminding consumers about the social relations that go into their food production. This acknowledgment of fetishization as a central problem in meat production, and a plea for the defetishization of meat, is a novel finding for media discourse on meat and points to the transformational potential of this crisis. The diagnostic framing of the ‘exploitative industry’ presented in news media reveals a possible disruption of the suppressive synergy that avoids meat-related controversies (Chiles 2017).

Irresponsible workers

The second diagnostic frame I highlight, ‘irresponsible workers’, is found marginally in only 4% of total articles (Table 2). Despite the structural issues in meat production being acknowledged by news media, a contradictory diagnostic frame that partly disperses blame to workers is still present, but is infrequently employed. Because previous research has documented xenophobic attitudes towards migrant workers in meatpacking plants, this frame’s limited frequency is potentially surprising (Gouveia and Juska 2002). Yet, it is significant because it brings, in a negative sense, visibility to the worker in the supply chain. However, unlike the ‘exploitative industry’ frame, this frame focuses on the behavior and lifestyles of the workers themselves, presenting workers as a prominent reason for the spread of the virus. Instead of recognizing the exploitative working conditions of the meat industry, the ‘irresponsible worker’ frame identifies the individual choices of workers as the reason why outbreaks are occurring in meatpacking plants. By side-stepping the problems within the meat industry, this frame describes outbreaks as consequences of worker’s actions:

Even if food-processing companies disinfect their plants and keep workers a safe distance from one another, employees could still be bringing the coronavirus into their facilities through their mode of transportation to work (Calefati, Fernandez, and Moreno 2020)

Not all workers are perceived as equally responsible for the spread of the virus in this frame; the blame is regularly directed towards a specific category of workers: migrant workers. This framing targets racialized workers by citing their ‘undocumented status’, living conditions, and behavioral habits:

They also rely heavily on workers that travel to visit family and friends in New York, a practice that could have helped spread the disease. (Calefati and Fernandez 2020)

Many are immigrants with limited language skills who fear losing their paychecks and can have difficulty practicing social distancing because they live in multigenerational homes or share rides. (Marbella 2020)

This framing presents workers’ behavior — such as sharing transportation to and from the workplace and their living conditions — as part of the reason for the virus’s impact on meatpacking plants. Implied in this framing is that slowing down production (to reduce the spread of COVID-19 in the workplace) is futile because it will be spread regardless by those who are employed in plants regardless. Meatpacking workers, particularly racialized workers, are seen as a problem for both being a worker and having family and friends. This frame also exposes contradictions regarding the need versus the blame of migrant workers in the meat industry and exacerbates exploitive public discourses about migrant workers in these host states (Geiger and Pécoud 2010). The ‘irresponsible workers’ frame offers an alternative to the notion of a structural origin for the problems in meatpacking: the dispersion of blame towards less powerful individuals — a strategy used to maintain hierarchies of power in capitalism.

Prognostic framing

I turn now to news media’s presentation of prognostic frames — the solutions or prescriptions suggested in response to the threat of COVID-19 to meat packaging plants. Whereas the first diagnostic framing points to historically rooted, structural issues, both prognostic frames propose solutions that aim to alleviate the immediate problems posed by the pandemic and return to the status quo. These competing frames offer disparate solutions: (1) ‘slow down production’ and (2) ‘protect the meat supply’. On the one hand, I find a prognostic frame that argues for the necessity of slowing or shutting down production in meatpacking plants. With 20% of articles (Table 2) adopting this frame, it is the most frequently articulated solution in my sample. Conversely, just 12% of articles (Table 2) employ a framing that argues that production must continue, even if it means workers must risk showing up to work. Beyond the apparent conflictual position of these two frames, it is significant that neither frame considers the possibility of transformation in meat production after the COVID-19 crisis is resolved – especially given the structural issues identified above in the diagnostic frame. When considering the extent and breadth of problems the ‘exploitative workers’ frame reveals, the prognostic framing is comparatively thin and is limited to just two possible courses of action.

Slow down production

The first prognostic frame employed by news media suggests that meat production must be slowed or shut down in response to the threat COVID-19 poses to workers and the community. The consensus within this framing is the necessity of reconsidering the pace of meat production to adhere to social distancing guidelines and allow for other safety measures:

“It’s certainly not like we’re out of the woods and the problems have stopped –we’re still seeing daily reports of outbreaks in plants” … “The recommended precautions are not anywhere sufficient to really prevent transmission. The only real way to prevent transmission would require really significantly slowing down and reconfiguring the way these plants operate, spacing out workers in a way that they’re just not willing to do.” (Axon, Bagenstose, and Chadde 2020, quoting Adam Pulver, attorney at the watchdog group Public Citizen)

The United Food and Commercial Workers union, which represents roughly 80% of beef and pork workers and 33% of poultry workers nationwide, has called for stricter measures than the CDC recommendations, including mandating that workers be spaced 6 feet apart on production lines. It has appealed to governors for help enforcing worker safety rules. The union also wants to get rid of waivers that allow some plants to operate at faster speeds. (Groves 2020).

It is argued in this frame that slowing down production would allow companies to follow health recommendations regarding the COVID-19 pandemic. In this regard, the problems that emerged from this crisis would be partially alleviated to prevent outbreaks. While the diagnostic frame discloses a range of exploitative practices in the industry, this prognostic frame attempts to mitigate the risks of transmission by adopting certain safety practices. The frame also implies that slowing or shutting down production might resolve some long-term issues that might emerge in the aftermath of the pandemic — such as jeopardizing the meat supply. A Des Moines Register article reports on concerns about the unintended consequences of Trump’s executive order: “With the president’s actions, we might end up in the same place all over again, with more workers sick and a larger disruption to the food chain” (Eller and Rodriguez 2020, quoting a supervisor for Black Hawk County, Iowa). In this vein, a possible larger disruption in the industry is a risk that slowing down the production is said to prevent:

At a daily COVID-19 press briefing Tuesday, state Health Commissioner Jan Malcolm said Trump’s plan to keep meat and poultry plants open seemed “counterintuitive” based on current coronavirus outbreaks that caused shutdowns. “At a time when we’re seeing such explosive increases in numbers of cases and the impacts on surrounding communities, it seems problematic to say the least,” she said (Spencer 2020).

The union that represents workers at a Vernon meatpacking plant where at least 153 have come down with COVID-19 called Monday for the immediate closure of the facility, saying there was no evidence measures taken to control the coronavirus were working. (Harriet 2020).

Overall, this frame proposes a change in the pace of meat production during the COVID-19 crisis to avoid spreading the virus. If the exploitative industry frame reveals long-term structural problems, then the solution offered by this frame is limited to resolving the immediate risks introduced by the pandemic. The recommended measures focus on containing the problem rather than questioning the concentrations of power in the meat industry (Johnston et al. 2009).

Protect the meat supply

The second prognostic frame suggests that production must continue, as normal, to protect the meat supply chain. This view is exemplified in former president Trump’s executive action in which he declares meatpacking to be an essential service and that plants should not be legally responsible for the health of their workers. For instance, an editorial in the Wall Street Journal defends Trump’s order:

His order pre-empts local officials who have ordered plants shut because they are afraid workers will spread the coronavirus. This fear is understandable since plants are often the largest employers in rural towns, and workers and their families -- many undocumented immigrants -- tend to live in cramped quarters… But America needs a food supply, and the Trump order offers liability protections to companies that protect workers by following in good faith the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Labor Department safety and health guidance. (Wall Street Journal 2020)

First, it should be noted that this quote incorporates the ‘irresponsible workers’ frame by suggesting plants were ordered shut because undocumented workers will spread the virus — indicating that the ‘irresponsible workers’ frame works to support a return to the status quo. Second, continuing operations in plants despite the risks posed by COVID-19 is justified by placing trust in corporations to implement and follow safety measures. In this sense, news media articles present quotes by leaders in the meat industry, suggesting the importance of protecting the meat supply by resuming production: “Most Ohio pork producers are not in a fire drill yet. We’re aware of the challenge, we understand we need to get packers open, and get these pigs to market. The worst that could happen now is to have another plant close.” (Welch 2020, quoting the owner of Heimerl Farms, a pork producer in Johnstown, Ohio). While the COVID-19 crisis presents serious challenges, the ‘protect the meat supply’ frame assumes that closing meat plants is the worst that can happen during the crisis. Additionally, this frame relies on the assumption that a robust supply of meat is necessary (a motivational framing) and that the consequences of disrupting the food supply chain by protecting workers and the community is too great:

“During this pandemic, our entire industry is faced with an impossible choice: continue to operate to sustain our nation’s food supply or shutter in an attempt to entirely insulate our employees from risk,“ …"It’s an awful choice; it’s not one we wish on anyone. It is impossible to keep protein on tables across America if our nation’s meat plants are not running.” (Newberry 2020, quoting a statement by Smithfield Foods).

The responsibility of feeding the nation appears to be the meat industry’s main role in this prognostic frame. The frame limits the public understanding concerning different modes of producing food or feeding the nation. By suggesting that we should overcome all risks to continue producing meat, this frame ignores the structural problems of the meat industry. Instead, it supports the dominance of corporate power, trusting the private sector to handle a public health crisis. This frame also suggests that even when diagnostic frames are robust and describe a series of topics to articulate the problem, we can find incongruencies between prognostic and diagnostic frames (Oleschuk 2020; Huddart Kennedy et al. 2018).

Motivational framing

Finally, I examine the motivational framing, which describes what is at stake and why collective action should be taken. Here I find two competing frames: (1) ‘workers must be protected’ and (2) ‘meat is necessary’. These frames describe why we need to act to either slow down production for the health of workers and the community or why the supply of meat is important and worth risking the lives of workers and the broader community to protect this supply. 52% of all articles adopt the ‘meat is necessary’ frame, while 44% of articles adopt the workers ‘must be protected’ frame (Table 2).

Moreover, an analysis of motivational frames can help to reveal what is important for an ideology by stressing what is worth protecting and what is perceived to be under threat. In this sense, the motivational frames I identify here displace the effects of the pandemic on animals by excluding their deaths from being seen as reasons for social action being taken. However, these deaths are lamented as a loss of use and/or exchange value; in other words, euthanizing animals is seen primarily as a loss of commodities.

Workers must be protected

The first motivational frame argues that workers must be protected, even if it means temporarily slowing down or stopping production. This frame supports the prognostic framing that argues for the importance of halting productive activities. Articles that adopt this frame appeal to humanist values by emphasizing the importance of protecting human lives — including workers, their families, and the broader community — over the profits of corporations. In other words, there is a perceived conflict between the interests of workers on one side and corporations (in collaboration with policymakers) on the other:

“They just decided those lives were OK to sacrifice …and for what?“ … “So many of (the) plants sent their pork to China. It wasn’t about feeding America.“ (Bagenstose 2020, quoting Debbie Berkowitz, former OSHA chief of staff).

“Workers are economically forced to go to work in life-threatening conditions that will also put the community at risk because our governor won’t take an action that is perceived to be anti-farmer.” (Hagemann 2020).

As this latter quote illustrates, protecting workers and the broader community from the threat of COVID-19 is framed as more important than the economic interests of the meat industry. Workers are presented as stuck between the dangers the virus poses to them and their families on the one side and the pressures of economic necessity, their employers, and their government on the other. Notably, this frame doesn’t strongly account for the meat industry’s structural issues and instead centers on the immediate risks that workers are facing during the pandemic. The motivation to protect workers is emphasized in a Des Moines Register article that quotes a Waterloo city councillor:

Amos said workers’ health is more important than meat supplies. “We could go without eating meat for a while,“ said Amos, who teaches machining at Hawkeye Community College. “And I eat meat” (Eller and Rodriquez 2020).

This framing implies, in a temporally limited sense, that workers’ health and well-being triumphs over the potential threat posed to the meat supply. In this sense, the risks that workers are exposed to only matter in a time of crisis, and their daily exposure to physical and psychological harm is of little concern.

Meat is necessary

The second motivational frame articulates that the meat supply must be protected, even if it means putting workers at risk. This frame follows from the prognostic frame that argues production must continue and promotes an ideology that asserts meat is necessary (Joy 2009). This framing maintains that a cheap supply of meat is needed for the maintenance of economic health, the health of the nation, and the availability of meat for consumers:

“We have a responsibility to feed our country. It is as essential as healthcare. This is a challenge that should not be ignored. Our plants must remain operational so that we can supply food to our families in America.“ (Telford 2020, quoting chairman of Tyson’s executive board, John Tyson)

Tyson last week shut down a major plant that is critical to the nation’s food supply after it was blamed for causing a COVID-19 outbreak in Waterloo, Iowa. But President Trump issued an executive order Tuesday requiring meat processing plants to remain open “to ensure a continued supply of protein for Americans.” (Overton 2020)

The exploitation of the industry is often justified through an ideology of nationalism that argues workers-at-risk must make a necessary sacrifice for their country to ensure an uninterrupted meat supply. The ‘meat is necessary’ frame implies the centrality of the meat industry and that COVID-19 outbreaks in plants pose a serious threat to the economy and the food supply chain. As reported in The Daily Times, a paper based in Salisbury, Maryland: “These outbreaks are not only a serious public health concern, they’re also a potential threat to Maryland’s leading agricultural industry and to our nation’s essential food supply chain” (Velazquez and Rentsch 2020, quoting governor of Maryland, Larry Hogan). Furthermore, this motivational frame reveals a cornerstone of the meat ideology — the objectification of nonhuman nature for human ends (Adams 1990; Kalof 2007; Longo and Malone 2006). Implicitly, both workers and animals are presented as disposable for the greater good of the nation and the economy.

Discussion

Imagination and ideology

This analysis of news media’s coverage of the COVID-19 pandemic on the meat industry has revealed a simultaneous process of commodity fetishism and defetishization. The ideological support of meat is not totalizing; cracks exist, allowing for opportunities for critique and challenge (Antonio 1981). A critical viewpoint is adopted in the diagnostic framing by bringing awareness to the structural problems in the meat industry and its history of exploitative practices (MacLachlan 2001). The diagnostic frame illustrates a thick democratic imagination and points to a partial process of defetishization in response to the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the meat processing plants (Huddart Kennedy et al. 2018; Johnston et al. 2009; Perrin 2006). This framing presents a complex understanding of how a broader crisis has revealed contradictions in the production of meat that have been previously hidden in news media (Chiles 2017). Evoking Berger and Pullberg (1965), the COVID-19 crisis has brought doubt to the taken-for-granted relations of meat production, and the human origins of meat are recognized. However, this defetishizing process is limited by the comparatively thin democratic imagination I find in the prognostic framings (Huddart Kennedy et al. 2018; Perrin 2006). The COVID-19 pandemic presented an opportunity to question the social reality and offer the possibility of alternatives to the status quo. A thick democratic imagination in the prognostic frame might seize this opportunity and suggest possibilities to transform the relations of meat production in ways that addresses the systemic problems associated with meat as identified in the diagnostic framing. Instead, the solutions provided in the prognostic frames are restricted to lessening the impacts of the pandemic that are perceived to be most urgent and a return to the status quo. In particular, I draw attention to two conflicting proposed solutions: slowing production to protect workers and the wider community or ensuring that production resumes to protect the food supply chain. These solutions suggest a short political horizon for social change; what is imagined to be possible is limited to returning to a formerly stable social order where contradictions remain but are no longer visible.

Furthermore, the thinness of this prognostic framing, as represented in newspapers, demonstrates the unwillingness and constrained ability to imagine and propose alternatives to a problem fundamentally rooted in capitalism (Huddart Kennedy et al. 2018). On the one hand, cheap meat is desirable, and there’s little impetus to imagine alternatives and a strong impetus to look past the problems. On the other hand, as cultural theorist Mark Fisher (2009, p. 19) notes, critiques of capitalism — such as those found in the diagnostic framing — are easily incorporated into capitalist ideology because it relies on a “structure of disavowal”: “so long as we believe (in our hearts) that capitalism is bad, we are free to continue to participate in capitalist exchange.” We continue to fetishize commodities (including meat) through our actions because we adopt a “cynical distance” towards the commodity and acknowledge the exploitation that goes into creating it (Žižek 1989, p. 24; Fisher 2009). In other words, acknowledging exploitation is insufficient if it cannot consider the possibility of political alternatives. This points to the critical role of imagination in any attempt to challenge an ideology. To critique the taken-for-granted nature of meat production, we must also be able to recognize that alternatives are possible.

These findings also raise questions about the limitation of news media in the process of defetishization. Do the public turn to news media expecting solutions or just to outline problems? Does news media merely reflect the desires of the public? While important, these questions cannot be answered in this present study. Future research must be open to investigating the sites and conditions where a democratic imagination can be fostered. In other words, our work must be oriented to not only understand the critiques that ‘reveal’ the hidden relations in capitalist processes but to apprehend how we can challenge structures of power and genuinely engage with critical, imaginative futures (Johnston et al. 2009).

The absent referent

In the motivational frames I highlight above, the focus is principally on the interests of humans and excludes COVID-19’s impacts on animals — especially those that were euthanized because they could not be processed. In this sense, the death of animals, the principal function of the slaughterhouse, remains mostly absent from the discussion of meat (Adams 1990). When news media discussed the pandemic’s consequences for animals, the focus was on the need to euthanize healthy animals to avoid economic waste. Animal death is only ‘revealed’ when made visible as a waste product; when animals are turned into food, their deaths are obscured (Adams 1990). Despite reporting on the deaths of millions of healthy animals, the animals themselves are reduced to rationalized, quantifiable, and objectifying terms.

While meat producers are motivated to avoid euthanasia, this is because it threatens their profits and not because they must kill more animals than is necessary. In this context, the death of animals is to be mourned because it is a waste of use/exchange value. Of course, these animals will die regardless of the pandemic — but their bodies will be disposed of rather than consumed, making it worth reporting on. This presentation distances the public from the realities of meat production by obscuring what goes on in meatpacking plants: the killing and disassembly of animals.

Conclusion

In this paper, I have identified a general process of defetishization through news media’s framing of the impacts of COVID-19 on the meat industry as rooted in broader structural problems. The labor conditions in slaughterhouses are challenged, and the experiences of workers are made visible through a thick description of a myriad of historical and structural problems that led to this crisis in meat production. However, I argue that this process is only partial. The incongruence between a diagnostic framing which gives attention to structural and historical problems rooted in capitalism, and a prognostic framing which views the only viable solution as returning to the status quo, is evidence of a thin democratic imagination that does not challenge the fetishized relations of meat production (Huddart Kennedy et al. 2018; Johnston et al. 2009; Perrin 2006).

Whereas the COVID-19 crisis has, to some degree, illuminated the social relations of meat production, this acknowledgment and critique co-exists within a framing that supports the status quo of industrial livestock production by minimizing the degree to which animals’ lives matter. By treating the deaths of animals as a tragic waste of product, this crisis has reinforced a reified view of non-human nature that sees animals as objects and obscures the social and ecological origins of meat products (Adams 1990). This reification ultimately supports and is supported by an economic system based on the accumulation and expansion of capital at the expense of humans and nonhuman animals. Nevertheless, this paper has argued against a totalizing view of ideology. It asserts that tensions between ideologies and social formations allow space for critiques even in the mainstream news media which has previously worked to hide the problems (Chiles 2017). This finding suggests that crises can lead to a public debate about complex, historical, and structural problems. However, the strategies proposed to deal with this crisis rely on a thin democratic imagination and do not acknowledge or envision structural transformations and alternative forms of relations between human and non-human nature.

Notes

Despite the emphasis on animal agriculture in this review, I do not wish to suggest that meat is inherently exceptional when compared to other commodities. Instead, I focus on meat production as a particularly illustrative example of how ideological structures support the forces of production which exploit non-human nature.

While outbreaks of COVID-19 at meatpacking plants have occurred since these dates, this selected time period captures the discourse surrounding a number of key events including Donald Trump’s executive order and the major outbreak at Sioux Falls, South Dakota. I also confirmed that these dates captured the bulk of media controversy in plants by searching ‘meatpacking’, ‘slaughterhouse’, and ‘meat processing’ in Google trends to confirm a spike in activity beginning in April and declining in July.

In addition to the 230 US articles, I also examined 35 Canadian articles to see if there were substantial differences in the settings. Results were not different enough to warrant a comparison, which was expected given the similar histories of meat production in these countries.

It should also be noted that not every article contained every framing task. For instance, many articles did not adopt a diagnostic frame to understand or assign blame to the problem and instead focused on what should or can be done (prognostic) or what is at stake (motivational).

References

Adams, C. J. 1990. Sexual politics of meat: a feminist-vegetarian critical theory. New York, NY: Continuum.

Allen, P., and M. Kovach. 2000. The capitalist composition of organic: the potential of markets in fulfilling the promise of organic agriculture. Agriculture and Human Values 17 (3): 221–232.

Antonio, R. J. 1981. Immanent critique as the core of critical theory: its origins and developments in Hegel, Marx and contemporary thought. The British Journal of Sociology 32 (3): 330–345.

Axon, R., K. Bagenstose, and S. Chadde. 2020. Coronavirus outbreaks climb at u.s. meatpacking plants despite protections, trump order. USA Today. https://investigatemidwest.org/2020/06/06/coronavirus-outbreaks-climb-at-u-s-meatpacking-plants-despite-protections-trump-order/ . Accessed December 26, 2022.

Bagenstose, K. 2020. As leaders warned of US meat shortages, overseas exports of pork and beef continued. USA Today. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/investigations/2020/06/16/meat-shortages-were-unlikely-despite-warnings-trump-meatpackers/3198259001/. Accessed December 26, 2022.

Bastian, B., S. Loughnan, N. Haslam, and H. R. M. Radke. 2012. Don’t mind meat? The denial of mind to animals used for human consumption. Personality And Social Psychology Bulletin 38 (2): 247–256.

Bateman, T., S. Baumann, and J. Johnston. 2019. Meat as benign, meat as risk: mapping news discourse of an ambiguous issue. Poetics 76: 101356.

BeMiller, H. 2020. Brown county’s latino community ‘terrorized’ by coronavirus, and the numbers show why. Green Bay Press-Gazette. https://www.greenbaypressgazette.com/story/news/2020/06/30/coronavirus-brown-county-hispanics-hit-hard-virus-outbreaks/5266090002. Accessed June 22.

Benford, R. D., and D. A. Snow. 2000. Framing processes and social movements: an overview and assessment. Annual Review of Sociology 26 (1): 611–639.

Berger, P., and S. Pullberg. 1965. Reification and the sociological critique of consciousness. History and Theory 4 (2): 196–211.

Broadway, M. 2007. Meatpacking and the transformation of rural communities: a comparison of brooks, alberta and garden city, kansas. Rural Sociology 72 (4): 560–582.

Broadway, M. J., and D. D. Stull. 2008. ‘I’ll do whatever you want, but it hurts’: worker safety and community health in modern meatpacking”. Labor 5 (2): 27–37.

Bryant, C. C. 2020. Inside a hotspot: voices from the floor of a meat-packing plant. Christian Science Monitor. https://www.csmonitor.com/Business/2020/0505/Inside-a-hotspot-Voices-from-the-floor-of-a-meat-packing-plant. Accessed December 26, 2022.

Bulliet, R. W. 2005. Hunters, herders, and hamburgers: the past and future of human-animal relationships. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Cairns, K., D. McPhail, C. Chevrier, and J. Bucklaschuk. 2015. The family behind the farm: race and the affective geographies of Manitoba pork production. Antipode 47 (5): 1184–1202.

Calefati, J., and B. Fernandez. 2020. Pa. has more coronavirus cases among meat plant workers than any other state, cdc says. The Philadelphia Inquirer. https://www.inquirer.com/business/retail/cdc-20200501.html. Accessed December 26, 2022.

Calefati, J., B. Fernandez, and J. F. Moreno. 2020. Beefs about safety as cases rise at plants. Philadelphia Daily News. http://myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquest.com%2Fnewspapers%2Fbeefs-about-safety-as-cases-rise-at-plants%2Fdocview%2F2396026855%2Fse-2%3Faccountid%3D14771. Accessed March 8, 2023.

Castree, N. 2001. Commodity fetishism, geographical imaginations and imaginative geographies. Environment and Planning A 33: 1519–1525.

Chiles, R. M. 2017. Hidden in plain sight: how industry, mass media, and consumers’ everyday habits suppress food controversies. Sociologia Ruralis 57 (S1): 791–815.

Czymara, C. S., A. Langenkamp, and T. Cano. 2021. Cause for concerns: gender inequality in experiencing the covid-19 lockdown in Germany. European Societies 23 (sup1): S68–S81.

Dillard, J. 2008. A slaughterhouse nightmare: psychological harm suffered by slaughterhouse employees and the possibility of redress through legal reform note. Georgetown Journal on Poverty Law & Policy 15 (2): 391–408.

Eagleton, T. 1991. Ideology: an introduction. London, UK: Verso.

Eller, D., and B. Rodriguez. 2020. Packing plantreaction is mixed: trump’s stay-open order sparks worker health worries; pork producers hopeful. Des Moines Register. http://myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquest.com%2Fnewspapers%2Fpacking-plantreaction-is-mixed%2Fdocview%2F2396113882%2Fse-2%3Faccountid%3D14771. Accessed March 8, 2023.

Fisher, M. 2009. Capitalist realism: is there no alternative? Winchester, UK: Zero Books.

Fitzgerald, A. J. 2010. A social history of the slaughterhouse: from inception to contemporary implications. Human Ecology Review 17 (1): 58–69.

Fitzgerald, A. J. 2015. Animals as food. East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University Press.

Gamson, W. A., and A. Modigliani. 1989. Media discourse and public opinion on nuclear power: a constructionist approach. American Journal of Sociology 95 (1): 1–37.

Geiger, M., and A. Pécoud. 2010. The politics of international migration management. Pp. 1–20 in The Politics of International Migration Management, edited by M. Geiger and A. Pécoud. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

Gouveia, L., and A. Juska. 2002. Taming nature, taming workers: constructing the separation between meat consumption and meat production in the U.S. Sociologia Ruralis 42 (4): 370–390.

Grabell, M., and B. Yeung. 2020. Emails show the meatpacking industry drafted an executive order to keep plants open. ProPublica. https://www.propublica.org/article/emails-show-the-meatpacking-industry-drafted-an-executive-order-to-keep-plants-open Accessed March 11, 2023.

Groves, S. 2020. Meatpackers cautiously reopen plants and coronavirus fears. The Philadelphia Tribune. https://www.phillytrib.com/news/health/coronavirus/meatpackers-cautiously-reopen-plants-amid-coronavirus-fears/article_47bf91e2-d545-50c7-8631-2188f98fe4b3.html. Accessed December 26, 2022.

Gunderson, R. 2011. From cattle to capital: exchange value, animal commodification, and barbarism. Critical Sociology 39 (2): 259–275.

Gunderson, R. 2014. Problems with the defetishization thesis: ethical consumerism, alternative food systems, and commodity fetishism. Agriculture and Human Values 31(1): 109–17.

Hagemann, K. 2020. How’d we get here? Over the decades, we made the meatpacking industry ‘too big to fail’. Des Moines Register https://www.desmoinesregister.com/story/opinion/columnists/iowa-view/2020/05/01/covid-19-iowa-how-meatpacking-industry-became-too-big-fail/3055086001/. Accessed December 26, 2022.

Hannigan, J. 2014. Environmental sociology. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Routledge.

Harriett, Ryan. 2020. Farmer john meatpackers demand closing of vernon plant struck by covid-19 outbreak. Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2020-05-25/farmer-john-meatpackers-demand-closing-vernon-plant-coronavirus Accessed December 26, 2022.

Hashem, N. M., A. González-Bulnes, and A. J. Rodriguez-Morales. 2020. Animal welfare and livestock supply chain sustainability under the covid-19 outbreak: an overview. Front Vet Sci. (2020) 7: 679.

Hobbs, J. E. 2021. The Covid-19 pandemic and meat supply chains. Meat Science. 108459.

Horkheimer, M., and T. W. Adorno. 1944. Dialektik der aufklarung. New York, NY: Social Studies Association, Inc. English edition: Horkheimer, M. and T.W. Adorno. 1979. Dialectic of enlightenment (trans: J. Cummings). London, UK: Verso.

Huddart Kennedy, E., J. R. Parkins, and J. Johnston. 2018. Food activists, consumer strategies, and the democratic imagination: insights from eat-local movements. Journal of Consumer Culture 18 (1): 149–168.

Jett, T. 2020. Advocates for meatpacking workers demand usda halt payments to tyson, jbs amid covid-19 outbreaks. Des Moines Register. https://www.desmoinesregister.com/story/money/business/2020/07/09/meatpackers-tyson-jbs-failed-protect-workers-civil-complaint-says/5408480002/ Accessed December 26, 2022.

Johnston, J., A. Biro, and N. MacKendrick. 2009. Lost in the supermarket: the corporate-organic foodscape and the struggle for food democracy. Antipode 41 (3): 509–532.

Joy, M. 2009. Why we love dogs, eat pigs, and wear cows: an introduction to carnism. San Fransisco, CA: Red Wheel/Weiser.

Kalof, L. 2007. Looking at animals in human history. London, UK: Reaktion books.

Kim, S. J., and W. Bostwick. 2020. Social vulnerability and racial inequality in covid-19 deaths in chicago. Health Education & Behavior 47 (4): 509–513.

Kojola, E. 2017. (Re)constructing the pipeline: workers, environmentalists and ideology in media coverage of the keystone xl pipeline. Critical Sociology 43 (6): 893–917.

Leroy, F., M. Brengman, W. Ryckbosch, and P. Scholliers. 2018. Meat in the post-truth era: mass media discourses on health and disease in the attention economy. Appetite 125: 345–355.

Longo, S. B., and N. Malone. 2006. Meat, medicine, and materialism: a dialectical analysis of human relationships to nonhuman animals and nature. Human Ecology Review 13 (2): 111–121.

Lukács, G. 1923. Geschichte und klassenbewußtsein: studien über marxistische dialektik. Berlin, Germany: Hermann Luchterhand Verlag. English Edition: Lukács, G. 1971. History and class consciousness: studies in marxist dialectics (trans: R. Livingstone). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

MacLachlan, I. 2001. Kill and chill. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press.

MacNair, R. M. 2002. Perpetration-induced traumatic stress in combat veterans. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology 8 (1): 63–72.

Marbella, J. 2020. Salisbury made a national list of coronavirus hot spots. how many cases came from its poultry plant? maryland won’t say. The Baltimore Sun. https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2020-05-24/coronavirus-outbreaks-occur-at-9-industrial-facilities-in-vernon. Accessed April 17, 2023.

Marx, K. 1867. Das kapital: kritik der politischen oekonomie. Hamburg, Germany: Verlag von Otto Meisner. English edition: Marx, K. 1976. Capital: a critique of political economy. London, UK: New Left Review.

Mccombs, M., and A. Reynolds. 2009. How the news shapes our civic agenda. In Media effects: advances in theory and research, eds. J. Bryant, and M. B. Oliver, 1–16. New York, NY: Routledge.

Newberry, L. 2020. Coronavirus outbreaks hits farmer john, 8 other plants in vernon. https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2020-05-24/coronavirus-outbreaks-occur-at-9-industrial-facilities-in-vernon. Accessed December 26, 2022.

O’Sullivan, V. 2020. Non-human animal trauma during the pandemic. Postdigital Science and Education 2 (3): 588–596.

Oleschuk, M. 2020. ‘In today’s market, your food chooses you’: news media constructions of responsibility for health through home cooking. Social Problems 67 (1): 1–19.

Oleschuk, M., J. Johnston, and S. Baumann. 2019. Maintaining meat: cultural repertoires and the meat paradox in a diverse sociocultural context. Sociological Forum 34: 337–360.

Overton, P. 2020. Poultry plant to idle for 3 days due to pandemic. Morning Sentinel http://myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquest.com%2Fnewspapers%2Fpoultry-plant-idle-3-days-due-pandemic%2Fdocview%2F2397277860%2Fse-2%3Faccountid%3D14771. Accessed March 8, 2023.

Pachirat, T. 2011. Every twelve seconds: industrialized slaughter and the politics of sight. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Patel, J. A., F. B. H. Nielsen, A. A. Badiani, S. Assi, V. A. Unadkat, B. A. Patel, R. Ravindrane, and H. Wardle. 2020. Poverty, inequality and covid-19: the forgotten vulnerable. Public Health 183: 110–111.

Perrin, A. J. Citizen speak: the democratic imagination in american life. Chicago, IL: Chicago University Press.

Sinclair, U. 1906. The jungle. New York, NY: Doubleday, Page & Co.

Skerritt, J. 2020. Tyson foods helped create the meat crisis it now warns against. Bloomberg. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-04-29/tyson-foods-helped-create-the-meat-crisis-it-now-warns-against. Accessed December 26, 2022.

Snow, D. A., and R. D. Benford. 1988. Ideology, frame resonance and participant mobilization. International Social Movement Research 1: 197–217.

Spencer, J. 2020. President signs order to reopen meat plants. Star Tribune. http://myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquest.com%2Fnewspapers%2Fpresident-signs-order-reopen-meat-plants%2Fdocview%2F2396014623%2Fse-2%3Faccountid%3D14771. Accessed March 8, 2023.

Taylor, C. A., C. Boulos, and D. Almond. 2020. Livestock plants and covid-19 transmission. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117 (50) 31706–31715.

Telford, T. 2020. Osha releases guidance for meatpacking firms to keep workers healthy. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2020/04/27/osha-releases-guidance-keep-meatpacking-workers-safe-amid-surging-cases-food-supply-fears/. Accessed December 26, 2022.

Velazquez, R., J. Rentsch. 2020. Delmarva chicken plant outbreaks to get cdc, fema help. md. nursing homes to test all. Delmarva Now. https://www.delmarvanow.com/story/news/local/maryland/2020/04/29/perdue-tysons-chicken-plants-larry-hogan-gives-coronavirus-mountaire-allen-harim-nursing-homes-tests/3048920001/ Accessed April 17, 2023.

Vermeir, I., and W. Verbeke. Sustainable food consumption: exploring the consumer “attitude – behavioral intention” gap. Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics. 19: 169–194.

Welch, J. 2020. Whole hog?: supply chain issue means too many hogs in Ohio but not enough pork. Marion Star http://myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquestcom%2Fnewspapers%2Fwhole-hog%2Fdocview%2F2399643138%2Fse-2%3Faccountid%3D14771. Accessed March 8, 2023.

Žižek, S. 1989. The Sublime object of ideology. London, UK: Verso.