Abstract

Well-being in retirement is thought to depend on person’s level of resources and how his or her resources change during retirement. However, to date few studies have directly investigated resource trajectories during retirement. The current study therefore examines how economic, personal, and social-relational resources change during the retirement transition for people retiring from paid employment and for people retiring from other, non-working labour market statuses (e.g. disability pension, homemaker, unemployment). Based on four representative baseline samples of the German Ageing Survey (1996, 2002, 2008, and 2014) and their respective 6-year follow-up interviews, we identified N = 586 retirees. We then used dual change score models to separately estimate the level and change in income, health, activity, family and non-family network size, and social support for people retiring from paid work (n = 384) and people retiring from other statuses (n = 202) adjusted for age, gender, education, region, period, and time since retirement. Overall, we found that resources changed only modestly during the retirement transition. Resource changes did, however, differ by last labour market status and sociodemographic characteristics. Income and social support declined and family networks increased for both those retiring from paid work and those retiring from other statuses. Leisure activities increased only for those retiring from paid work. No changes in health or non-family networks were observed. People with many resources before retirement also had many resources after retirement. We conclude that retirement affects resources less than researchers often expect. Accordingly, differences based on labour market remain despite retirement.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Acock AC (2005) Working with missing values. J Marriage Fam 67:1012–1028. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2005.00191.x

Baker M, Stabile M, Deri C (2004) What do self-reported, objective, measures of health measure? J Hum Resour. https://doi.org/10.2307/3559039

Barbosa LM, Monteiro B, Murta SG (2016) Retirement adjustment predictors—a systematic review. Work Aging Retire 2:262–280. https://doi.org/10.1093/workar/waw008

Behncke S (2012) Does retirement trigger ill health? Health Econ 21:282–300. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.1712

Bosse R, Aldwin CM, Levenson MR et al (1993) Change in social support after retirement: longitudinal findings from the normative aging study. J Gerontol 48:P210–P217. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronj/48.4.P210

Cornwell B, Schafer MH (2016) Social networks in later life. In: George LK, Ferraro KF (eds) Handbook of aging and the social sciences. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 181–201

Damman M, van Duijn R (2017) Intergenerational support in the transition from work to retirement. Work Aging Retire 3:66–76. https://doi.org/10.1093/workar/waw023

Dannefer D (2003) Cumulative advantage/disadvantage and the life course: cross-fertilizing age and social science theory. J Gerontol Ser B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 58:S327–S337. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/58.6.S327

De Vaus D, Wells Y, Kendig HL, Quine S (2007) Does gradual retirement have better outcomes than abrupt retirement? Results from an Australian panel study. Ageing Soc 27:667–682. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X07006228

Dorfman LT (2013) Leisure activities in retirement. In: Wang M (ed) The Oxford handbook of retirement. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 339–353

Ekerdt DJ, Baden L, Bossé R, Dibbs E (1983) The effect of retirement on physical health. Am J Public Health 73:779–783. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.73.7.779

Ezzy D (1993) Unemployment and mental health: a critical review. Soc Sci Med 37:41–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(93)90316-V

Fasang AE (2010) Retirement: institutional pathways and individual trajectories in Britain and Germany. Sociol Res Online. https://doi.org/10.5153/sro.2110

Fasang AE (2012) Retirement patterns and income inequality. Soc Forces 90:685–711. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/sor015

Gallo WT (2013) The association of retirement with physical and behavioral health. In: Wang M (ed) The Oxford handbook of retirement. Oxford University Press, New York, pp 325–338

Halleröd B, Örestig J, Stattin M (2012) Leaving the labour market: the impact of exit routes from employment to retirement on health and wellbeing in old age. Eur J Ageing 10:25–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-012-0250-8

Hansson I, Buratti S, Thorvaldsson V et al (2018) Changes in life satisfaction in the retirement transition: interaction effects of transition type and individual resources. Work Aging Retire 4:352–366. https://doi.org/10.1093/workar/wax025

Henning G, Lindwall M, Johansson B (2016) Continuity in well-being in the transition to retirement. GeroPsych 29:225–237. https://doi.org/10.1024/1662-9647/a000155

Hobfoll SE (1989) Conservation of resources: a new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am Psychol 44:513–524. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.44.3.513

Huxhold O, Fiori KL, Windsor TD (2013) The dynamic interplay of social network characteristics, subjective well-being, and health: the costs and benefits of socio-emotional selectivity. Psychol Aging 28:3–16. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030170

Hyde M, Ferrie JE, Higgs P et al (2004) the effects of pre-retirement factors and retirement route on circumstances in retirement: findings from the Whitehall II study. Ageing Soc 24:279–296. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X03001624

Kim JE, Moen P (2002) Retirement transitions, gender, and psychological well-being: a life-course, ecological model. J Gerontol Ser B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 57:P212–P222. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/57.3.P212

Klaus D, Engstler H, Mahne K et al (2017) Cohort profile: the German ageing survey (DEAS). Int J Epidemiol 46:1105-1105g. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyw326

McArdle JJ (2009) Latent variable modeling of differences and changes with longitudinal data. Annu Rev Psychol 60:577–605. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163612

Mein G, Martikainen P, Hemingway H et al (2003) Is retirement good or bad for mental and physical health functioning? Whitehall II longitudinal study of civil servants. J Epidemiol Community Health 57:46–49. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.57.1.46

Morris JK, Cook DG, Shaper AG (1994) Loss of employment and mortality. BMJ 308:1135–1139. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.308.6937.1135

Motel-Klingebiel A, Engstler H (2008) Einkommensdynamiken beim Übergang in den Ruhestand. In: Künemund H, Schröter KR (eds) Soziale Ungleichheiten und kulturelle Unterschiede in Lebenslauf und Alter. Springer, Wiesbaden, pp 141–159

Muthén L, Muthén B (2010) MPlus—user’s guide, 6th edn. Muthen & Muthen, Los Angeles

OECD (2018) Net pension replacement rates (Indicator). https://data.oecd.org/pension/net-pension-replacement-rates.htm. Accessed 07 Feb 2018

Ross CE, Mirowsky J (2006) Social structure and psychological functioning. In: Delamater J (ed) Handbook of social psychology. Springer, Boston, pp 411–447

Rowe JW, Kahn RL (2015) Successful aging 2.0: conceptual expansions for the 21st century. J Gerontol Ser B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 70:593–596. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbv025

Schmälzle M, Wetzel M, Huxhold O (2019) Pathways to retirement: are they related to patterns of short- and long-term subjective well-being? Soc Sci Res 77:214–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2018.10.006

Segel-Karpas D, Bamberger PA, Bacharach SB (2013) Income decline and retiree well-being: the moderating role of attachment. Psychol Aging 28:1098–1107. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034672

Strauß S, Ebert A (2013) Einkommensungleichheiten in Westdeutschland vor und nach dem Renteneintritt. In: Vogel C, Motel-Klingebiel A (eds) Altern im sozialen Wandel: Die Rückkehr der Altersarmut?. Springer, Wiesbaden, pp 253–272

Szinovacz ME (2003) Contexts and pathways. In: Adams GA, Beehr TA (eds) Retirement: reasons, processes, and results. Springer, New York, pp 6–52

Van Den Bogaard L, Henkens K, Kalmijn M (2014) So now what? Effects of retirement on civic engagement. Ageing Soc 34:1170–1192. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X13000019

van Tilburg TG (2009) Retirement: effects on relationships. In: Reis HT, Sprecher S (eds) Encyclopedia of human relationships, vol 3. Sage, Thousand Oaks, pp 1376–1378

Wang M (2012) Retirement: an adult development perspective. In: Whitbourne SK, Sliwinski MJ (eds) The Wiley-Blackwell handbook of adulthood and aging. Blackwell, Oxford, pp 416–432

Wang M, Shi J (2014) Psychological research on retirement. Annu Rev Psychol 65:209–233. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115131

Wang M, Henkens K, van Solinge H (2011) Retirement adjustment: a review of theoretical and empirical advancements. Am Psychol 66:204–213. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022414

Westerlund H, Kivimäki M, Singh-Manoux A et al (2009) Self-rated health before and after retirement in France (GAZEL): a cohort study. Lancet 374:1889–1896. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61570-1

Wetzel M, Huxhold O (2016) Are leisure activity and health interconnected after retirement: educational differences. Adv Life Course Res 30:43–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alcr.2016.03.007

Wetzel M, Mahne K (2016) Out of society? Retirement affects perceived social exclusion in Germany. Z Gerontol Geriatr 49:327–334. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00391-016-1036-y

Wetzel M, Huxhold O, Tesch-Römer C (2016) Transition into retirement affects life satisfaction: short- and long-term development depends on last labor market status and education. Soc Indic Res 125:991–1009. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-0862-4

Wilson J (2000) Volunteering. Annu Rev Sociol 26:215–240. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.26.1.215

Yeung DY (2018) Adjustment to retirement: effects of resource change on physical and psychological well-being. Eur J Ageing 15:301–309. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-017-0440-5

Yeung DY, Zhou X (2017) Planning for retirement: longitudinal effect on retirement resources and post-retirement well-being. Front Psychol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01300

Acknowledgements

The German Ageing Survey is funded by the German Federal Ministry for Family, Senior Citizens, Women and Youth (Grant 301-1720-2/2).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Responsible editor: M. J. Aartsen.

Appendix

Appendix

We followed the same procedure for each resource variable. We started with the most flexible model in which all parameters were estimated freely. We then tested whether setting the intercepts of both groups as equal (fix int) decreased model fit. Next, we examined whether fixing the slope terms or allowing different slope terms for the two groups resulted in better model fit (fix sl or free sl). If fixing the intercepts to be equal and the slopes to be unequal resulted in better model fit, we retested whether allowing the intercepts to differ with fixed slopes improved model fit. In the last step, we examined whether each of the maximum of four level and change parameters significantly differed from zero. Table 3 displays the results of the model tests. All models with significantly better fit over the preceding model are in bold. The final, most parsimonious model is in italics.

For available income, model fit decreased significantly when the intercepts (A2, A3) were set to be equal across groups regardless of whether the slopes were estimated freely or fixed. Model fit increased when the intercepts were estimated freely and the slopes were fixed (A4:A1; Δχ2 = − 2.94; Δdf = 1; p ≥ 0.05). Model fit decreased when each parameter was set to zero (A5, A6, A7). Accordingly, the most parsimonious model was characterized by two different intercept terms and a common slope term which were all unequal to zero, indicating that the two groups of retirees had different income pre-retirements but experienced the same rate of change during retirement.

For physical health, both the intercepts (C2:C1; Δχ2 = − 0.67; Δdf = 1; p ≥ 0.05) and the slopes (C3:C2; Δχ2 = − 0.00; Δdf = 1; p ≥ 0.05) could be set to be equal across the two groups, and the intercept parameter and slope parameter could be set to be zero without reducing model fit (C5:C3; Δχ2 = − 0.03; Δdf = 1; p ≥ 0.05; C6:C5; Δχ2 = − 3.10; Δdf = 1; p ≥ 0.05). The final model was thus characterized by no differences in level and no change for either group, indicating that there were neither pre-retirement differences nor changes in physical health for either group.

For leisure activities, the intercepts for the two groups could be set as equal without decreasing model fit (B2:B1; Δχ2 = − 3.15; Δdf = 1; p ≥ 0.05). Setting the slopes to be equal reduced model fit (B3). Setting the intercept parameter to zero did not decrease model fit (B5:B2; Δχ2 = − 0.22; Δdf = 1; p ≥ 0.05). The slope for people retiring from paid work was not equal to zero (B6), whereas the slope for those retiring from other, non-working statuses could be set to zero without affecting model fit (B7:B5; Δχ2 = − 0.19; Δdf = 1; p ≥ 0.05). The final model was thus characterized by an intercept of 0 for both groups, with an increase for people retiring from paid work and no change for people retiring from other, non-working statuses.

For family network size, setting the intercepts to be equal decreased model fit (D2). Setting the slopes to be equal also decreased model fit (D3). Setting the intercepts as unequal and the slopes as equal affected model (D4:D1; Δχ2 = − 0.12; Δdf = 1; p ≥ 0.05). Successively setting each intercept to zero did not affect model fit for either model (D5:D1; Δχ2 = − 2.80; Δdf = 1; p ≥ 0.05; D6:D1; Δχ2 = − 1.73; Δdf = 1; p ≥ 0.05). The equal slope parameters could not, however, be set to zero (D6). The final model thus indicated that both groups of retirees began with the same family network size (0) and experienced the same slight increase in family network size during retirement.

For non-family network size, intercepts were unequal and the slopes were equal (E4:E1; Δχ2 = 0.08; Δdf = 1; p ≥ 0.05). The intercept for those retiring from paid work could be set to zero (E5:E4; Δχ2 = − 2.09; Δdf = 1; p ≥ 0.05), but not the intercept for people retiring from other non-working statuses. Setting the slope parameters to zero did not decrease model fit (E7:E5; Δχ2 = − 2.30; Δdf = 1; p ≥ 0.05). The final model thus indicated different intercepts for the two groups (lower intercept for people retiring from non-work statuses) and no change for either group.

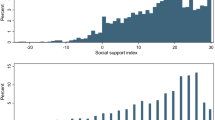

Finally, for social support, neither the intercepts (F2:F1; Δχ2 = − 3.57; Δdf = 1; p ≥ 0.05) nor the slopes were statistically different (F3:F2; Δχ2 = − 0.76; Δdf = 1; p ≥ 0.05) between the two groups. The intercept did not significantly differ from zero (F5:F3; Δχ2 = − 0.01; Δdf = 1; p ≥ 0.05), but the slopes did. Thus, the final model suggests that the intercept of both groups was 0 (i.e. there were no pre-retirement differences in social support) and that social support decreased for both groups.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wetzel, M., Bowen, C.E. & Huxhold, O. Level and change in economic, social, and personal resources for people retiring from paid work and other labour market statuses. Eur J Ageing 16, 439–453 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-019-00516-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-019-00516-y