Abstract

Coal is expected to remain a significant power supply source worldwide and shifting to carbon-neutral fuels will be challenging because of growing electricity demand and booming industrialization. At the same time, coal consumption results in severe air pollution and health concerns. Improvement in emission control technologies is a key to improving air quality in coal power plants. Many scientists reported removing air pollutants individually via conventional control methods. However, controlling multiple pollutants combinedly using the latest techniques is rarely examined. Therefore, this paper overviews the current and advanced physical technologies to control multi-air pollutants synergistically, including carbon control technologies. Also, the paper aims to examine how potential air pollutants (e.g., PM2.5, SO2, NOx, CO2), including mercury from the coal-fired power plants, cause environmental impacts. The data synthesis shows that coal quality is the most significant factor for increasing air emissions, regardless of power plant capacity. It is found that selecting techniques is critical for new and retrofitted plants depending on the aging of a power plant and other socio-economic factors. Considering the future perspective, this paper discusses possible pathways to transform from linear to a circular economy in a coal power plant sector, such as utilizing energy losses through energy-efficient processes and reuse of syngas. The article provides an in-depth analysis of advanced cost-effective techniques that would help to control the air pollution level. Additionally, a life cycle assessment-based decision-making framework is proposed that would assist the stakeholders in achieving net-zero emissions and offset the financial burden for air pollution control in coal-fired power plants.

Graphical abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The demand for fossil fuels (e.g., coal) has risen because of the industrial revolution, land-use changes, and standard of living, consequently leading to climate change (Avagyan 2021). Recently, an atmospheric CO2 of nearly 417.41parts per million (ppm) globally has been observed by December 2021, setting the highest trend despite the economic strike due to the COVID-19 pandemic (NASA 2021). Coal accounted for 27% of the global primary energy supply and has been extensively used in electricity production; however, burning coal contributed to 15 billion tonnes of CO2 per annum worldwide (Buonocore et al. 2021). China is considered the world's largest coal consumer and has a capacity of 1.1 billion kW of installed coal-fired power plants in 2019, followed by India, the USA, Germany, Russia, and Japan (Wang 2020). In coal-fuelled power plants, electricity is produced by converting thermal energy onto electric energy by combusting coal in a boiler (Osman et al. 2021). The boiler heats water at a specific temperature range between 1500 and 1600 °C (Cebrucean et al. 2020). As a result, water vapours are produced that provide power for the turbine in a conventional coal-fired power plant. Then, the turbine turns the generator, which generates electricity (Wang 2020). During the process, several air pollutants such as sulfur dioxide (SO2), nitrogen oxide (NOx), particulate matter (PM), carbon dioxide (CO2), and mercury (Hg) are produced (Finkelman et al. 2021). In addition, fly ash is produced as a residue during coal burning (Marinina et al. 2021). The pollutants cause respiratory illnesses and lung disease (Deng et al. 2019). Mercury has been associated with neurological damage in humans and development issues in other animals (Yang et al. 2007). CO2 is the primary greenhouse gas and contributes to global warming (Ades et al. 2019). The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) suggested limiting global warming to 1.5 °C, and the Paris agreement (2015) also highlighted the urgency to achieve carbon neutrality and net-zero emissions globally (Finkelman et al. 2021). A recent Emissions Gap Report 2021 shows that the updated nationally determined contributions and mitigation pledges under the Paris agreement only reduced 7.5% of projected 2030 GHGs emissions (UNEP 2021). Also, any further delay in implementing national policies would likely increase global warming to 2.7 °C by the end of this century (UNEP 2021).

The impact of the coal power plant on the environment is a central discussion of many scientists, and recent studies on the emissions from coal power plants, particularly those without advanced control techniques, raised a question about controlling multiple hazardous pollutants, including gaseous emissions and heavy metals (Campbell 2020; Chen et al. 2020). However, most studies only focus on dust and CO2 emissions (Nassar et al. 2017; Finkelman et al. 2021). Therefore, this article discusses all the potential air emissions (e.g., PM2.5, SO2, NOx, CO2), including heavy metals and their associated environmental impacts, which would help insight into a coal power plant and emission inventory. Phasing out coal is practically a challenging task because of various socio-economic issues in various regions, including South Asian countries, and transition to net zero-emission in the coal power supply sector is not an easy pathway (Buonocore et al. 2021). It requires a detailed analysis of many other factors such as coal quality, economy, and plant efficiency (Ballabio et al. 2021). Moreover, the aging of coal power plant infrastructure is not documented and discussed widely (Casey 2019). Average pollution from old power plant infrastructure may contribute to over 800,000 premature deaths per year globally and is associated with many health issues (Finkelman et al. 2021). Therefore, despite the advancement in the latest techniques, it is critical to improving the air quality associated with coal power plants (Wilczyńska-Michalik et al. 2020). This paper discusses all these factors in detail while examining the recent and advanced air pollution control techniques, including energy-efficient technologies and carbon–neutral fuels. Many past studies have evaluated individual control technologies and compared a variety of conventional air pollution control methods (e.g., baghouse, wet scrubbers, selective catalytical reduction) for specific air pollutants in the coal power plant (Leung et al. 2014; Tang et al. 2020). For example, Wang et al. (2020) examined ultra-low emission technologies (e.g., wet electrostatic precipitators) to remove emissions from the selected coal plants in China. However, advanced techniques that could control multiple pollutants as a single unit or combinedly are rarely examined. A few studies discussed the latest strategies and their fundamental processes to remove carbon, including adsorbent methods (Campbell 2020; Chen et al. 2020). This review provides examples of nanomaterial and advanced membrane technologies as a post-combustion CO2 control method. Even though the improvement in physical air pollution control techniques, previous efforts have not been devoted to developing an automated tool that can function as an integrated decision support and environmental control system for power plants that would help policy-makers to select the appropriate solution (Zhang et al. 2019). Therefore, in this paper, the state-of-the-art technologies are examined with the latest examples of various coal power plants.

This paper first examines the environmental impacts from the deployed coal-fired power plants in the significant coal consumer countries (e.g., USA, China, and European countries). Then this study critically reviews the current strategies and advanced physical technologies to control multi-air pollutants synergistically, including carbon removal methods. Subsequently, the paper conceptualizes a systematic and novel framework for managing air pollution while focusing on a future perspective of a sustainable and cost-effective solution in coal power plants.

Materials and method

Data collection

The peer-reviewed literature published in the years 2020 and 2021 until now and relevant past studies were searched. Articles mainly were identified from database searches in Scopus and google scholar using PRISMA guidelines. In addition, the references of relevant records were searched in the web of science to obtain articles that may not have been found in the other database searches. The following search terms were used: "Air pollution from coal power plant AND environmental impact"; "coal power plant AND climate change OR carbon emission"; "Air pollution control techniques AND coal power plant"; "Carbon capture and storage AND coal power plant"; "Renewable energy resources OR carbon neutral fuels AND coal power plant"; "Life cycle assessment AND Modelling in coal power plant"; "Decision analysis OR Multicriteria methods AND coal power plant"; "Circular economy approach in coal power plan". All terms were searched using free text in title, abstract and controlled vocabulary.

We retrieved information from the selected 70, 40, 32 articles through google scholar, Scopus, and Web of Science respectively and considered them as identified articles. We collected the following data for each study: authors, country, year of publication, journal, study design, modelling method, potential air pollution emissions and their control techniques in coal power plant, study outcome, and other critical comments. The articles with duplicate information were excluded. Figure 1 shows the structure of selected papers for this study and eligibility criteria. After selecting the most relevant articles, only 82 records are screened and any duplicate results, ambiguous information is excluded.

Recent status of coal power plants and environmental impact

Updated emissions of major air pollutants and their ecological impacts

The burning of coal generates certain air pollutants (PM2.5−10, SO2, NOx), mercury, VOCs, CO2, and other heavy metals (Lead, Cadmium, Arsenic) that have devastating impacts on ambient air quality, local people, and ecosystems (Finkelman et al. 2021). In China, coal-fired power plants are significant sources of air pollution-related premature deaths (Wang 2020). In the USA, poor ambient air quality in the coal power plants region affects nearly 2 million people per annum, with a monetized value exceeding 100 billion USD per year (Finkelman et al. 2021). Russell et al. (2017) examined that closing three coal power plants near Pittsburgh had reduced 9% of PM2.5 in the area. Lysack (2015) reported that Alberta burnt more coal than other provinces in Canada and has more than 700 emergency visits to hospitals annually linked with hazardous air pollution due to coal combustion. Every year, European countries reported 3,000 premature deaths and approximately 8,000 cases of chronic lung diseases in children associated with poor air quality because of coal-fuelled power plants. Figure 2 illustrates the PM2.5 and SO2 pollution caused by the 16-lignite coal-fired power plants in southeast European countries (EU) (Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, North Macedonia, and Montenegro) in 2016. In these Western Balkans, the average coal power plant emits 20 times more sulfur dioxide (SO2) and 16 times more particulate matter (PM) than average European' coal power plants.

Air pollutant modelling dispersion caused by lignite coal-fuelled power plants in Western Balkans countries in Europe a PM2.5 annual mean; b SO2 annual mean (adapted by Casey (2019))

Particulate matter (≤ 10 µm in diameter) is mainly observed in coal power plants (e.g., fly ash during the combustion process) (Wilczyńska-Michalik et al. 2020). The PM10 emissions from European coal plants range from 1030 to 6324 tonnes per year (Casey 2019). In China, 7.5% of the country's PM2.5 emission is from coal power plants (Wang 2020). In Canada, power plants burning coal accounted for 75% and 61% of PM10 and PM2.5 emissions, respectively (Casey 2019). Likewise, more than 92% of the PM2.5 emissions were generated by the power plants in the USA, of which 96.4% burned coal (Wilczyńska-Michalik et al. 2020). PM2.5 is directly related to health issues and it is reported that a decrease of 10 µg/m3 in PM2.5 concentration would increase the life expectancy by 0.61 years (Wang 2020).

Major gaseous pollutants such as NOx and SO2 are emitted into the atmosphere, further reacting with water vapours and oxygen in the air to form nitric acids and sulfuric acid, respectively, and responsible for causing acid rain (Tang et al. 2020). Acid rain is harmful to structures and corrodes buildings (Deng et al. 2019). Also, acid rain can change freshwater pH, affect aquatic ecosystems, and damage crops (Finkelman et al. 2021). Due to wind speed, NOx and SO2 can transport away from the source and cause acidic rain to longer distances. Significant contributors of SO2 from coal-fired power plants in Europe are Ukraine (27%), followed by Turkey (24%), Serbia (15%), and Bosnia (11%) (Casey 2019). Whereas significant share in NOx emission contribution is by Turkey (20%), Germany (16%), followed by Ukraine (16%), and Poland (14%). In 2016, the Serbian power plant Kostolac B (emitted 128,000 tonnes of SO2) and Ugljevik, Bosnia (emitted 127,524 tonnes of SO2) was responsible for 25% of SO2 coal pollution across EU and Southeast Europe (also called western Balkans). In China significant reduction in SO2, NOx, and PM2.5 emission reduction has been observed for 2015–2019 (Wang 2020). Overall, in the USA, China, Japan, and the EU, many coal power plants installed air pollution control equipment such as flue gas desulfurization to reduce SO2 emissions low NOx burners to reduce NOx emissions (Casey 2019). Another reason for emission levels declined is national policies and strict regulations (Wang 2020). Figure 3 shows the SO2 and NOx emission trend in the USA from 1997 to 2020. Annual U.S. SO2 and NOx have reduced by 88% and 76%, respectively in power plants between the period, 1997 and 2019 due to clean air act amendments (CAAA), acid rain program imposed a cap on the gaseous emissions from coal and residual-fuel oil-fired power plants (Finkelman et al. 2021).

source: U.S Energy Information Administration (EIA 2021)

USA Coal-fired power plants gaseous pollutant emission trend from 197 to 2020. Note: Based on the annual average of 504 coal power plants across the USA. Data

Mercury content varies in coal between 0.01 and 1.5 g per ton of coal (Wang 2020). Mercury from the atmosphere can deposit onto the surface through wet as well as dry deposition processes. Ballabio et al. (2021) found a statistically significant relation between soil mercury levels and coal use in Europe's large power plants, proving that mercury from power plants is linked with higher mercury deposition in their vicinity. The mercury can enter the aquatic ecosystem where a small amount (< 10%) is changed to methyl mercury through natural bacteria action that bioaccumulates and become a part of the food chain (Yang et al. 2007). Ultimately, mercury may potentially cause human health risks through fish consumption (Wang 2020). The Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment (CCME) has determined that the significant levels of mercury in fish across Canada permit efforts to reduce mercury emissions to protect aquatic life as well as human health (Yang et al. 2007). Some international agreements are also signed, including the "North American Regional Plan on Mercury" since Canada gets ten times more mercury than it emits each year because mercury is stable in the atmosphere and can transport longer distances (Rallo et al. 2012).

Liu et al. (2018) statistically analysed that the coal-fuelled power generation unit sizes ≥ 600 MW with the capacity of 422 GW emitted 24 tons of mercury. In comparison, ≤ 300 MW size with a total of 204GW emitted 23 tons of mercury. It implies that coal quality in both the capacity units was the same as the observed difference of mercury emission was 1 ton. Overall, in 2015 annual mean of mercury intensity was 18.3 g/GWh across China's coal power plants (Yang et al. 2007). According to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), an annual average contribution from various US coal power plants are 24 pounds of mercury (i.e., 5 percent less than 2019) and a maximum of 343 lbs of mercury in 2020 (EIA 2021). Russia contributed the highest (66%) in mercury emission from coal combustion, followed by Europe (53%), India (52%), China (44%), and North America (43%). The low level of mercury emission in the USA compared to other countries is because the Hg and Air Toxics Standards mandate the Hg emissions reductions from power generation sources, including coal-fired power plants (Finkelman et al. 2021). VOCs are also one of the significant potential pollutants emitted from coal power plants. The warming temperature provides suitable conditions to have photochemical reactions between VOCs and NOx in the atmosphere to form ground-level ozone, a major component of smog (Li et al. 2015). Peng et al. (2021) estimated that the life cycle VOC emissions during the coal-power plant process contributed 1.78 × 10–2 − 9.85 × 10–2 (kg/MWh). According to the 2017 national emission inventory, the USA's coal-fuelled electricity generation contributed 17 × 103 tons of VOCs, 22% reduced from 2014 (USEPA 2021). In China, coal-fired power plants are a significant source of VOCs and account only for 4.1% of the country's total VOCs emissions (Peng et al. 2021). For this reason, VOCs from power plants received little attention in comparison to other gaseous pollutants.

Contribution of carbon emissions to climate change

The production of electricity from coal power plants accounted for 46% of the world's total CO2 (Bassano et al. 2020). The emissions of CO2 for every kilowatt-hour of electricity generated depends on the type of coal consumed. For example, 860 gCO2 /kWh is produced by using anthracite, and 1,020 gCO2/kWh is emitted by burning lignite (Tang et al. 2020). Figure 4 shows that the average annual CO2 emissions from coal-fired power plants of China are higher than European countries and the USA. Recent studies show that in 2013 almost 51% of China's coal power plants were in water-stressed regions (Wang 2020). While many other countries are shifting to renewable resources and reducing their carbon emissions, it is difficult for China to phase out coal in those regions. In 2020, the USA further reduced CO2 to 1.58 (Gt) produced during electricity generation (see Supplementary Fig. S1). Canada has lowest CO2 emission as few provinces used coal as a fuel for electricity generation and 60% of resource shared for electricity production is hydro (Bassano et al. 2020).

The greenhouse gases are responsible for trapping the sun's heat in the lower layers of the atmosphere and contributing to global warming. Mounting past evidence for the influence of warming temperature change on the hydrological cycle is considered as one of the severe impacts of climate change, including sea level rises, melt glaciers, alteration in precipitation patterns, heat waves, droughts, and decrease soil moisture (Ades et al. 2019). The globally averaged surface temperature in 2020 (combined land and ocean) was 0.98 °C, considered the second warmest year since the last century (NOAA 2021). It is predicted that global temperature may reach 1.5 °C by 2030 if it continues it increases at the same rate because of anthropogenic activities, including CO2 intensification (Ades et al. 2019). High water bodies' temperatures are projected to affect the water quality and are responsible for extreme events, including floods (NOAA 2021).

Current technologies to manage air pollution in coal power plant

Extended physical technologies to control multi-air pollutants

The emissions of SO2 are dependent on two critical factors: sulfur content in the coal burnt and efficiency of treatment technologies (Deng et al. 2019). Emissions control systems are typically based on sorbents used to scrub the pollutant from flue gas, known as flue gas desulfurization (FGD) (Lysack 2015). FGD technologies are further classified as wet or dry. Slurry or wet by-products are produced in the wet FGD (WFGD), and flue gas leaves the absorber saturated with moisture. In dry FGD (DFGD), waste is dry in characteristics, and flue gas is not saturated (Deng et al. 2019). This technique is predominately used for low to medium sulfur-based coal but can be applied to high sulfur content coals. In the sorbent injection method, sorbents are usually in powder or slurry (alkaline reagents such as lime) form injected upstream of flue gas (Hunt and Sewell 2015). In the fluidized bed (FB) method, limestone is preferred to precipitate pollutants during the coal combustion process (Lysack 2015). According to the 2019–2020 database of 504 coal-fired power plants in the USA, 35% of coal-fired power plants used wet limestone scrubbing, a conventional example of an acid-based chemical reaction (EIA 2021) (see Fig. S2a). The base usually comprises calcium carbonate and magnesium carbonate in the limestone (Buecker 2006). Other significant technologies used in the USA are wet lime FGD (18%), dry lime FGD (16.2%), fluidized bed limestone injection (6.1%), and dry sorbents injection (2.7%). Interestingly, 14% of the power plants in the USA do not have any control equipment for SO2. In China, 92.9% of plants are equipped with limestone or gypsum FGDs, followed by seawater and ammonia FGDs (Wang 2020). Since 2011, the Chinese government has revised the SO2 emissions limits for plants (35 mg/m3), resulting in further improvement in SO2 emission control in the coal-fired power plants and are strict as compared to USA (160 mg/m3) standards (Wang 2020). In Japan, 98% of the plants installed FGDs in 2014 (Deng et al. 2019). Whereas WFGDs is installed almost in all the plants in Germany. EU standards for SO2 emissions are based according to the plant capacity, i.e., 50–100 MW (400 mg/m3), 100–300 MW (200 mg/m3), and > 300 MW (150 mg/m3), but still allow more emissions in comparison to North America and South Asian countries (Rallo et al. 2012). PM removal by the WFGD technology is less costly than wet electrostatic precipitator (WESP) (Deng et al. 2019). Wu et al. (2019) investigated that the particles with larger diameters have more removal efficiency using WFGD application as compared to particles with smaller diameters (e.g., 28.7% for PM1.0, < 39.6% for PM2.5, and 50–60% for PM10).

Removal of mercury emission is the top priority in many countries, and the preferable method to remove mercury is activated carbon injection (ACI) (Yang et al. 2007). In the USA, until 2008, almost 90 full-scale ACI systems have been installed to coal-fired power generators (Zhao et al. 2017). Considering halogens, (e.g., Bromine) present in the composition of activated carbon in the ACI method, Hg0 (gas-phase elemental mercury) is further oxidized by halogens after physically absorbed by the sorbent and convert C–Br to form HgBr2. HgBr2 may react with oxygen-containing functional groups, generate C-O-Hg, finally desorbs to form HgO (Yang et al. 2007). One of the limitations of ACI is that if carbon is low in halogen, a large amount of activated carbon may require to control the Hg. In many places, Hg+2 (gas-phase oxidized) is removed synergistically with other pollutant removal methods such as DFGDs (Tian et al. 2020) and WFGDs (Ballabio et al. 2021) because of its solubility in water. The particle-bound mercury (HgP) is removed with dedusting control equipment such as electrostatic precipitators (ESP) (Wang 2020). Large-sized particles of Hg0 are difficult to removal using FGDs and ESP because of less solubility and volatility. They can be removed along with NOx using selective catalytic reduction (SCR) using the oxidation process (Zhao et al. 2017).

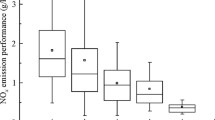

The most widely used methods to control NOx emissions in many countries are the low NOx burner (LNB) technology (Jiang et al. 2021) and selective catalytic reduction (SCR) (Schreifels et al. 2012). In the 1990s, China's coal-fired power plants started to use the LNB, and in 1999, SCR was installed in the 600 MW unit of the Fujian Zhangzhou Houshi Power Plant (Wang 2020). China has a stringent standard of 50 mg/m3, followed by the USA NOx limit of 117 mg/m3 for coal-fired power plants (Wang 2020). Given the increasingly strict environmental protection standards, NOx emission limit cannot be achieved using LNB technology alone (Jiang et al. 2021). In the USA, the majority of the plants are equipped with the combination of SCR and LNB along with overfire Air (OFA), followed by the combination of SCR and LNB and SCR and OFA (see Fig. S2b). OFA is an advanced technology that diverts the combusted air from the main combustion zone and reduces 30–40% more NOx than regular LNB (Jiang et al. 2021). The development of an advanced catalyst with a wide temperature operating range and catalyst regeneration are primary research focus for future studies (Rallo et al. 2012).

The particulate matter emission control technologies for coal-fired power plants have been developed since the 1960s, including cyclones (Wang 2020). The particulate size and composition generated during coal combustion depend on the coal quality, the boiler type, and capacity (Rallo et al. 2012). In the USA, 43% of the installed capacity of the coal-fired power plants are ESPs, followed by 29.5% of baghouse (EIA 2021) (see Fig. S2c). Furthermore, using two PM control devices in series has been applied to many plants to control better. For example, 12.1% combination of wet scrubbers and ESP, 7.5% series of the baghouse and ESP (EIA 2021). It is also observed that the WESP has been installed with the ESP, baghouse, or scrubbers in the USA. In China, the most common treatment options to control particulate matter for power plants are ESP, fabric filter (FF), a combination of ESP and WESP (Wang 2020). The integrated particulate controls and WFGD systems may also reduce 70% mercury (Rallo et al. 2012). The filterable particulate matter (FPM) and condensable particulate matter (CPM) are major constituents of total particular matter (TPM). CPM is vapor phase at stack conditions but condenses and/or reacts on cooling and dilution in the ambient air to form solid or liquid PM immediately after discharge from the stack and is difficult to monitor. Thus, in recent years, the final emission of CPM has been received wide attention (Wang et al. 2020).

Activated coke is one of the advanced techniques to control multi-pollutants such as SO2, NOx, and mercury in a coal-fired power plant (Tavoulareas 2005). Activated coke comprises two main processes, i.e., adsorption and desorption, including by-product recovery as an optional step (Tian et al. 2020). Sulfur dioxide is adsorbed when flue gas passes through activated coke and produces sulfuric acid as a by-product (Li et al. 2020b). Particulate matter can also be reduced to 80–85% in this process if the inlet has a concentration below 200 mg/Nm3 (Tavoulareas 2005). Mercury is absorbed on the coke up to 1.7 mg/g-coke at a temperature below 180 °C (Yang et al. 2007). In addition, ammonia is injected into the flue gas, and activate coke decomposes NOx to nitrogen and water while acting as a catalyst (Li et al. 2020b). Activated coke gets saturated because of sulfuric acid and needs to regenerate through desorption (Tian et al. 2020). This technique is commercially available in Japan and Germany (Li et al. 2020b).

Electrocatalytic oxidation (ECO) is a pilot-scale technology that can remove multi-pollutant (SO2, NOx, Hg, and PM) from the flue gas. The ECO is the combination of proven technologies such as pre-existing electrostatic precipitator (to remove fly ash and particulates), ECO reactor (that oxidizes the gaseous pollutants), and WESP that captures aerosols, including HgO, that pass through the absorber (Boyle 2002). Besides controlling primary emissions, ECO produces nitric and sulfuric acid that can be used to produce gypsum and fertilizer, which can be sold to offset the operating costs of the processing system (Li et al. 2020b). Usually, ECO is integrated with carbon control technology at the post-treatment stage (Bui et al. 2018). The ECO is initially designed by the Powerspan company and has operated commercially at 50 MW coal R.E. Burger power station (coal having 2–4% sulfur), Ohio, in 2004 (Jones 2010). Furthermore, Powerspan has upgraded "ECO2™," which uses a regeneratable ammonia solvent to remove CO2 from flue gas (Boyle 2002). The pilot-scale ECO2 ™ achieved 90% CO2 removal (20 tons/day) for a 1-MW flue gas stream (Boyle 2004). Overall, more testing is required to use this technology on a larger scale. Table 1 shows the removal efficiency of various multi-pollutant control techniques, their cost, and applicability.

Carbon removal and storage technologies

CO2 is formed during the coal combustion process, and therefore the carbon control techniques are mainly categorized as (1) pre-combustion, (2) oxyfuel combustion, and (3) post-combustion (Bassano et al. 2020). In the pre-combustion CO2 removal pathway, coal is combusted during the presence of air/O2 to produce syngas, i.e., a mixture of carbon monoxide and hydrogen (Eq. 1), which is then used to fire the combustion turbine in a power plant (Leung et al. 2014). Ultimately, syngas undergoes, "water to gas shift" stage, and CO is converted to CO2, as shown in Eq. 2 (Osman et al. 2021). Afterward, CO2 is separated; it can be stored using various methods such as chemical absorption, adsorption, and membrane separation (Cao et al. 2020). The removal of CO2 in pre-combustion is much easier than the oxyfuel and post-combustion method because of the high concentration of CO2 in the syngas due to the water to gas shift stage (Osman et al. 2021).

Integrated gasification combined cycle (IGCC) is a pre-combustion decarbonization method (Osman et al. 2021). In this emerging technology, gas and steam turbine processes are used (Leung et al. 2014). The syngas produced during the gasification process is used as fuel in a gas turbine, having electrical power (Marinina et al. 2021). Whereas in a combined cycle, "exhaust heat" from the gas turbine is used in a Heat Recovery Steam Generator (HRSG) to generate steam for the steam turbine cycle that produces electricity (Feng et al. 2014). IGCC has successfully installed many new and retrofit to existing plants such as 618 MW facility unit at Duke Energy Edwardsport, Indiana (Osman et al. 2021), 315 MW Tampa Polka IGCC power plant, Florida (Osman et al. 2021), and 250 MW plant in Nakoso, Japan (Amick 2016). Although the IGCC technique help to control air pollutants, however, there is still a need to focus on other environmental media such as water pollution. For instance, the Wabash River project, USA, did not meet permit compliance for water (1998–2001) because of elevated levels of heavy metals (e.g., arsenic, cyanide, and selenium) (Han et al. 2019; Siddiqui and Dincer 2020). These heavy metals arise from the current feedstock in the IGCC unit and end up in condensed vapours and leave the process via wastewater (Amick 2016). One of the biggest challenges in commercializing IGCC is its high capital cost (1200–1600 ($/kW) (Han et al. 2019). IGCC process promotes the production of as a H2 that can be used as a fuel after purification in cells, transportation or as a building block in the production of value-added chemicals (Osman et al. 2021).

In oxyfuel combustion, pure oxygen (O2) (> 95%) is used instead of air for coal combustion and produces flue gas consists of CO2 and water vapours (Stanger et al. 2015). It is easy to remove CO2 from the exhaust stream through the cooling process because of its high concentration in flue gas (Wienchol et al. 2020). NOx emissions are remarkably reduced along with the volume of exhausted flue gas (75%) due to oxygen (Leung et al. 2014). Moreover, this decarbonization CO2 control is energy efficient with a 4% low-efficiency penalty compared to post-combustion methods (8–12%) (Wienchol et al. 2020). One of the barriers in such a route is the availability of pure oxygen and its supply, which requires a proven technology such as cryogenic distillation that increases the project's cost (Stanger et al. 2015). Thus, there is a need to investigate further low-cost air separation methods (how to separate oxygen from the air) such as oxygen-transport membrane and ion transport to find novel solutions of air separation (Wienchol et al. 2020). Flame stability can be particularly sensitive to the amount of oxygen in the primary stream. Therefore, fixing the flame is necessary and requires optimizing oxygen levels in the primary stream to avoid the risk of autoignition (Zhang et al. 2019). Doosan Power Systems' Oxy Coal™, (Renfrew, UK) provided the 30MWth Oxy Coal™ burner in the boilers as a proven solution to have good flame stability, along with the integrated air separation (removes nitrogen, which makes up 78% of air), and the subsequent flue gas cleaning equipment, ESP and WFGD (Wang 2020). One of the advantages of using oxyfuel combustion method is that it can be employed for both pre-dried lignite and bituminous coal. The Vattenfall Project, Germany (30 MW pilot plant) and the Callide Oxyfuel Project, Queensland, Australia are the largest oxy-fuel projects at demonstration level (Wienchol et al. 2020).

The post-combustion control and separates CO2 in an oxidant environment from the flue gas after combustion (Chao et al. 2021). Prior to the CO2 capture, the exhaust flue gas emissions pass through other pollutants control treatment units such as dedusting, denitrification, and desulfurization. The input stream fed to the absorbers mainly contains CO2, N2, and H2O (Marinina et al. 2021). This route is preferably retrofitted to existing small-scale power plants with a recovery rate of CO2 is 800tons/day (Cao et al. 2020). The major challenge is that the CO2 level is low (7–14%) in flue gas, and the cost associate with the control unit is high to reach the concentration > 95.5% (Osman et al. 2021). The most common post-combustion methods are (1) absorption, (2) adsorption, and (3) membrane separation technologies (Cao et al. 2020). In physical absorption, CO2 is absorbed into the solution without any chemical reaction, based on Henry's law at low temperature and high CO2 partial pressures (Zhang et al. 2019). In chemical absorption, the reaction between CO2 and specific solvents usually occurs at low CO2 partial pressure (Marinina et al. 2021). The typical organic chemical absorbents are amine and alkaline compounds such as sodium hydroxide, potassium carbonate, and sodium carbonate (Fang et al. 2020). Mono-ethanolamine (MEA) is the most efficient sorbent with 90% absorption efficiency (Li et al. 2020a). The standard amine-based CO2 absorption unit design consists of two stages (Kumar et al. 2018). The flue gas first is passed through an absorption column where the solvent removes most of the CO2 by chemical absorption, and the second is a stripping column where heat is applied to release the CO2 and regenerate the solvent (Fang et al. 2020). Other significant and fast reactive solvents are piperazine (PZ) and anion-functionalized ionic liquid (Osman et al. 2021). However, because of the volatile nature of PZ, it is less stable than MEA (Leung et al. 2014). The critical issues in amine-based absorption are: (1) equipment corrosion, and (2) amine degradation that leads to the potential release of harmful compounds such as nitrosamines and nitramines into the atmosphere (Fang et al. 2020). The exhaust gas temperature could be maintained below 150°F (65 °C) to minimize the degradation problem (Li et al. 2020a). The chilled ammonia process could also be applied as it uses aqueous ammonium salts that have minor degradation issues in contrast to amine-based solvents (Bui et al. 2018).

Another effective post-combustion method is adsorption-based CO2 removal that follows intermolecular force between gases and the surface of certain solid materials, such as activated carbon (Osman et al. 2021). The adsorbents are usually arranged as packed beds of spherical particles (Borhan et al. 2019). Unlike absorption, solid sorbents are used in the adsorption process, such as zeolites, activated carbon, and polymers (Marinina et al. 2021). The activated carbons have usually small pores of various sizes (2–500 angstroms) and large surface areas (Marinina et al. 2021). Whereas, zeolites are crystalline in structure with uniform pores (smaller size than activated carbon), and polymers are crosslinked with high surface areas and large pore sizes (Osman et al. 2021). The removal efficiency of any gaseous pollutant depends on the adsorbent's characteristics such as surface area, pore size, the nature of the adsorbate (solubility, functional groups, molecular weight and size), functional groups, polarity, solubility), and the condition of the operating conditions (e.g., temperature, pressure) (Guo et al. 2020). Since there are several factors that can influence the adsorption process, Therefore it is important to understand the impact of these individual factors on the adsorption behaviour (Fang et al. 2020). The mesoporous siliceous, e.g., MCM-41, MCM-48, and SBA-15, stimulate high CO2 adsorption because they possess many defective–OH groups and large surface areas that can accommodate CO2 easily (Bhagiyalakshmi et al. 2010). In comparison among the three, SBA-15, if grafted with 3-chloropropyl amine hydrochloride (3-CPA), shows maximum adsorption of CO2 at 25 °C followed by MCM-41/CPA and MCM-48/CPA (Bhagiyalakshmi et al. 2010). Either pressure swing (PS) or temperature swing (TS) is employed to capture and release CO2 in a cyclic adsorption/desorption sequence. The regeneration time in TS is longer than PS, but high recovery (80%) can be achieved (Marinina et al. 2021). The kinetic behaviour of a gas–solid adsorption process using porous adsorbents can be analysed using kinetic models such as pseudo-first-order kinetic model and pseudo-second-order kinetic model (Guo et al. 2020). For example, the experimental results of modified potassium-based silica aerogel microstructure indicated consistency with both pseudo-first order (R2 = 0.9866) and pseudo-second-order kinetic model (R2 = 0.9605), showing that reaction was controlled by both physical adsorption and chemical adsorption (Borhan et al. 2019). In another study, the pseudo-second kinetic model showed the best fit (R2 = 0.939) to the experimental data indicated that the rubber-seed shell-based activated carbon is effective for CO2 adsorption applications. Overall, the potential of the adsorption capacity can be evaluated by the magnitude of coefficient regression R2 and its proximity value toward unity (Guo et al. 2020).

The role of nanomaterials in air pollution control, especially CO2 control, has shown considerable potential because of their chemical characteristics and higher surface area (Kumar et al. 2020; Osman et al. 2021). For example, the amine-containing solid sorbent based on Montmorillonite (MMT) nano-clay has a high specific surface area with 7.5 wt.% of CO2 control capability with an amine (Kumar et al. 2020). Many studies show that nanoparticles can also improve the efficiency of existing technologies, such as an activated carbon supported Copper (II) oxide (CuO) nanoparticle that can increase 70% of the CO2 adsorption capacity (Boruban and Esenturk 2018). Other examples of nanomaterials are zeolite NaA nanocrystals, Graphene, mesoporous silica nanotubes, and immobilized silver nanoparticles, with higher CO2 adsorption capacity (Kumar et al. 2020). However, most of these materials are used at a lab or pilot scale and need more studies to be used commercially.

Membrane technologies are the most convenient post-combustion technique that allows CO2 to pass through the membrane and remove it from flue gas (Cao et al. 2020). The crucial design and operational parameters for membranes are selectivity and permeability of the membrane structure (Leung et al. 2014). The membrane technology can be operated as (1) Gas separation membranes (GSM) operate on the principle of diffusion (Cao et al. 2020), and (2) Gas absorption membrane (GAM) consist of microporous solid membranes in contact with an aqueous absorbent (Zhang et al. 2019). In GSM, porous structures in the membrane permit the preferential permeation of CO2 from one side of the membrane to the other, whereas, in GAM, CO2 diffuses through the membrane and is then absorbed by MEA (Leung et al. 2014). Examples of GSM are polymeric, ceramic, metallic membranes, and polymer-silica nanocomposite membrane (Osman et al. 2021). These membranes are more efficient than GAM for CO2 separation (Zhang et al. 2019).

Advanced strategies to reduce air pollution

Energy-efficient process technologies

Pulverized coal (PC) combustion is the most widely used technology for commercial-scale power generation worldwide (Tumanovskii et al. 2017). The coal is grounded into fine particles (∼100 μm) and then injected with heated combustion air through several burners into the lower part of the furnace (Han et al. 2019). The heat is generated through the burning of suspended particles and is transferred into the steam cycle. In the past few years, the improvements in the technology sector have primarily involved strengthening plant thermal efficiencies by raising the steam pressure and temperature. Based on the differences in pressure and temperature, the technique is categorized into three tiers (Osman et al. 2021): (1) Subcritical (S) − operating with steam pressures around 2400 psi at 1000ºF, (2) Supercritical (SC) − emerging application for higher pressure and temperatures (above 3208 psi and 706ºF) power plants where higher efficiencies can be achieved, and (3) Ultra-supercritical (USC)—higher pressures and temperatures than SC (above 4350 psi and 1112 F) and considered as most efficient and advanced technique (Han et al. 2019). SC and USC power plants are mainly operated in China, the USA, Japan, Europe, Russia, and other regions (Cebrucean et al. 2020). By the end of 2017, China had 103 sets of 1000 MW USC units (Fan et al. 2018). In Canada, Keephills 3, Edmonton used SC for 463 MW capacity power plant and the integrated air quality control system including low NOx burners, desulfurization technique, activate carbon injection system, and baghouse (Tumanovskii et al. 2017). Taizhou Power Plant (Taizhou City, Jiangsu Province, China) has a USC efficient double-reheat technology, ensuring that the unit designed gross power efficiency is no less than 47.92% (low heating value) (Akash et al. 2016). In China, ultra-low emission technologies (e.g., SCR, ESP, wet dust precipitator, and limestone-gypsum wet flue-gas desulfurization) have been practiced to meet the national regulations (Tumanovskii et al. 2017). Table 2 represents the average efficiency and costing summary of pulverized coal combustion techniques.

The thermodynamic analysis of power plants has growing interest in many scientists as it helps to identify losses and in turn gives insights to make the system or technique more energy efficient (Han et al. 2019; Siddiqui and Dincer 2020). For instance, Han et al. (2019) performed a thermodynamic analysis of pulverized coal power plant and observed that the environmental impact, including NOx emissions, would be increased by up to 90%, while plant thermal efficiency decreased when the plant was operated in low loads (i.e., coal input). Almost two-thirds of the energy used during conventional coal-based electricity generation is wasted in heat and emitted into the atmosphere. Additional energy losses occur during electricity distribution to the end-users (Chen et al. 2020). Using the thermodynamic and energy analysis approach, wasted heat can be utilized again such as the combined heat and power (CHP) technique allows utilizing this heat and achieving 30% more energy-efficient than decentralized and limited-capacity coal-fired boilers (Zhang et al. 2019). The two most crucial CHP configurations are combustion turbine, also known as reciprocating engine, with heat recovery unit and steam boiler with a steam turbine (Siddiqui and Dincer 2020). In combustion turbines, systems burn coal to run generators to produce electricity and use heat recovery devices to utilize the heat from the engine or turbine. This heat is converted into thermal energy, usually in steam or hot water (Chen et al. 2020). In steam turbines, the process begins by producing steam in a boiler that turns a turbine to run a generator to produce electricity (Siddiqui and Dincer 2020). Thus, the steam leaving the turbine can also be used to produce thermal energy. These systems can use various fuels, such as coal, natural gas, oil, and biomass (Zhang et al. 2019).

Circulating fluidized-bed (CFB) technology is a clean coal combustion platform developed to burn low-grade coal or coals which are difficult to burn in a PC boiler (Deng et al. 2019). CFB has strengthened with improved installed capacity from 25 to 320 MW (Chen et al. 2020). In 2009, the world's first CFB integrated with SC-PC plant was commissioned in Poland named Lagisza Power Station with a total installed power capacity of 460 MW (Deng et al. 2019). The technique has impregnated activated carbon to remove SO2 and Hg from CFB flue gas in the pre-treatment section. In 2013, China built a 600 MWe Baima SC-CFB power plant that remarkably reduces SO2 (design value: 192 mg/m3), NOx (design value: 112 mg/m3), and PM (design value: 9 mg/m3) (Cai et al. 2017). By 2016 more than 70 SC-CFB power plants are installed across China with 350 to 660 MW installed capacity (Cai et al. 2017). The significant advantage of CFB is that it can burn both traditional fuels and carbon–neutral fuels, including biomass, waste coals, tires, and processed waste materials (Kalita et al. 2013). The technology can be used to reduce CO2 emissions to the atmosphere significantly. CFB technology does not have burners or a flame within its furnace (Chen et al. 2020). CFB uses the fluidization method to mix and circulate fuel particles with limestone, where the limestone captures the sulfur oxides as they are formed. At the same time, the low-burning temperature minimizes the formation of nitrogen oxides (Adams et al. 2020). Also, by injecting ammonia into the CFB, NOx can be reduced by half (Adams et al. 2020). Overall, CFB projects are growing at an annual rate of 35% with China, Japan, and Australia (Deng et al. 2019).

Switch to carbon–neutral fuels

Many countries plan to phase out the coal power plants and switch to other renewable resources such as hydro/water, solar, and wind. The decline in percentage share of coal from electricity and energy production has been prioritized across the globe at the government level to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and improve the air quality. The phase-out of coal limits the development of new coal mines, power plants, associated infrastructure and encourages shifting other renewable resources (Brown and Spiegel 2019). In the USA, the coal-based electricity generated capacity reduced dramatically from 327 GW (1024 coal power plant units) in 2000 to 259 GW (268 number of operating plants) in 2019, and approximately 71GW is planned to close in upcoming years (EIA 2021) (see Fig. S3). In European countries, including Finland, Spain, Germany, Poland, Netherland, the nominal coal power plant in 2019 has been dropped from 189 to 143 GW since 2000 in support of the 2015 Paris Agreement (Casey 2019) (see Fig. S3). As of mid-2020, several countries (e.g., France, Germany, Belgium) have planned to shut down their last coal-burning power plants or closed their coal mines in 2019 (Campbell 2020), respectively. Several other countries have committed to phasing out coal use, including Canada, Mexico, Hungary, UK, Denmark, Finland, South Korea, and Japan (Casey 2019). The coal power plant phase-out in many European and North American countries is offset by growth in China (973GW installed capacity) and India (221 GW installed capacity). More than 3,000 coal-fired power plants have been massively deployed in China since 2011 (Buonocore et al. 2021). According to the World Electric Power Plants (WEPP) database, China has announced 199 GW new coal-fired power plants in the pipeline (i.e., more than the current coal capacity in the EU countries). Furthermore, it is expected that India's coal consumption would increase by 4.6% per annum through 2024 with 94GW under-construction coal plants and by 12% in Russia in upcoming years (Casey 2019).

One of the reasons many countries are shifting away from coal might be the low input cost of renewable resources (Finkelman et al. 2021). Secondly, policy changes may turn coal-fired power plants into non-performing assets and become a liability in the future (Casey 2019). Economy analysts forecasted the coal's share of U.S. electricity generation could dip to just 10% in five years, down from 50% a decade ago (Chen et al. 2020). However, it's not an easy transition because of the growing electricity demand driven by booming industrialization. There is a need to understand the knowledge gap between electricity savings by industries, displaced coal-fired power capacity, and air emission reductions from electricity generation (Casey 2019).

Many challenges could be faced while coal phase-out requires, including socio-economic conditions such as workers, enterprises, communities, and lower-income households associated with the coal industry (Finkelman et al. 2021). In addition, phasing out subsidies to coal-fired power and establishing carbon pricing may lead to higher energy and fuel prices (Brown and Spiegel 2019). There are barriers to ultimately shifting to renewable resources, such as the upfront capital cost to construct and install hydro, solar, and wind power facilities (Buonocore et al. 2021). The installed capacity for renewable energy resources in 2019 is highest in China, followed by the USA, Canada, and Germany (see Fig. S4). In contrast to coal and natural gas, renewable resources are decentralized solutions (Brown and Spiegel 2019). However, they require siting and transmission of power through new infrastructure. The government may initiate subsidy reforms that help to shift away from coal, such as Germany recommended providing €40 billion until 2038, to compensate and give training to coal workers and reduce the economic burden on electricity consumers and utility companies in coal intensive areas (Campbell 2020).

In the USA, the average share of electricity generated from coal has reduced from 52.8% in 1997 to 27.4% in 2018 (EIA 2021). In 2017, 359 coal-powered units at the electrical utilities across the US, with a total nominal capacity of 256 GW, were present (compared to 1024 units at nominal 278 GW in 2000) (EIA 2021). In 2019 and 2020, the plant number was further declined to 268 and 228, respectively) (EIA 2021) (see Fig. S5). Compared to the USA, China has the highest coal share in electricity generation in 2020, as shown in Fig. 5. Hydropower plants produced about 60% of the total electricity generation in Canada, 17.3% in China, 10.1% in France, and 7.3% of entire U.S. electricity generation. Hydropower plants use flowing water to run a turbine connected to a generator (Campbell 2020). Wind energy is about 30.6% in Germany, 24.8% in the UK, and 8.4% of total U.S. electricity in 2020. Wind turbines convert wind energy into electricity (EIA 2021). Solar energy provided about 11.4% of total German electricity in 2020, the highest solar percentage share compared to other countries. The two most common solar based electricity production methods are photovoltaic (PV) and solar-thermal power. PV conversion generates electricity directly from sunlight in a photovoltaic cell (Brown and Spiegel 2019). Most solar-thermal power systems utilize steam turbines to produce electricity (Casey 2019). Natural gas is the largest source—about 40%—of the U.S. and 34.5% of UK electricity generation in 2020. Natural gas is an alternative to coal used mainly in steam turbines and gas turbines to generate electricity (National Grid ESO UK 2021). France has nuclear energy as the highest resource of electricity production (71.6%), followed by the USA, UK, and Canada 20%, as shown in Fig. 5. Nuclear plants run steam turbines to produce electricity through nuclear fission (Campbell 2020).

Future perspective to combat air pollution

Improvement in air pollution control technologies is a key to reducing air pollutant emissions in the coal-based power plant sector. While recognizing the research gaps of literature studies, future research should overcome the following limitations: (1) Most of the treatment technologies are focused on reducing air pollution by comparing techniques and adjusting the energy mix, such as using a combination of coal with biomass (Buonocore et al. 2021). However, there is an immense need to conduct more research on circular economy to improve thermal efficiency that would help to reduce the quantity of coal utilized and ultimately decrease the level of air pollutant emissions (Wang et al. 2020). For example: Combine heat and pressure (CHP) explore the waste heat and recover it from expanding the heat capacity of existing plants. (2) Small units should be discouraged due to the low combustion efficiency of boilers and a higher level of air pollutant emissions emitted from coal-fired power plants (Wang et al. 2020). There is a need to understand the knowledge gap of the relationship among electricity savings by industries, emission inventory from the coal-fired power, and air emission control techniques from electricity generation (Korre et al. 2010). The existing inventories rely on average emission factors due to a lack of real-time monitoring and are subject to uncertainty analysis. Also, the average emission factors do not consider individual power plants' heterogeneous and time-varying features (Tang et al. 2020). Therefore, there is a need for a system that can consider the trade-offs between environmental requirements and economic objectives, decrease the possibility of pollutant risk, and help the power plant reduce environmental-related capital and operation costs. Sustainability in the energy sector is accomplished by adopting several integrated environmental management tools as proposed in Fig. 6. The environmental management system may include (1) life cycle assessment (LCA) modelling that helps to generate emission inventory of the power plant and assess environmental impacts, (2) integrated environmental modelling that can predict the pollutant concentration at the receptor level and assist in estimating risk, (3) and selection of best practicable air pollution control method by multi-criteria decision (MCD) technique.

Life cycle assessment analysis approach

The CO2 removal and air pollution control in coal power plants offer several alternatives with different energy consumption rates and consequent environmental impacts (Leung et al. 2014). It is imperative to understand that emission reduction technologies should not trade-offs increasing any other environmental burdens (e.g., resource depletion, water pollution, and acidification) while focusing on improving air quality and mitigating climate change (Korre et al. 2010). Life cycle assessment quantifies emissions throughout the power generation's life cycle and represents it as emission inventory that enables decision-makers to assess all the potential environmental impacts of air pollution management solutions. For example, Korre et al. (2010) investigated that the coal type is the dominant factor in determining the environmental impact potential. Moreover, lignite has the highest contribution to global warming (998 kg CO2 eq./1 MW of electricity) followed by sub-bituminous (969 kg CO2 eq./1 MW of electricity) and bituminous (846 kg CO2 eq./1 MW of electricity) PC (wall fired; dry bottom boiler) combustion, due to the low heating value of lignite. The choice of coal is limited to local availability resulting in geographical differences in emissions from coal-fired power plants, such as lignite has been used in Germany for many years. LCA model could be developed considering coal composition and heating value when calculating the mass flow of coal, air requirements, and environmental emissions. Korre et al. (2010) also examined those environmental burdens associated with MEA chemical absorption (post-combustion) CO2 removal are more as compared to PZ solvent (Global warming kgCO2 eq/MWe: MEA (179), PZ (160); Acidification (Kg SO2 eq.): MEA (0.47), PZ (0.31)). Koornneef et al. (2008) investigated three different scenarios of pulverized coal combustion using the LCA method in Netherland power plants, including S–PC, USC–PC, and chemical absorption using MEA. The study concluded that air pollutants (NOx, SO2, Hg, PM) were reduced significantly in USC, followed by the chemical absorption and S–PC method; however, CO2 removal rate was high in the chemical absorption method followed by USC and S–PC (Koornneef et al. 2008). Thus, from the cradle to the grave, an entire chain perspective is needed to assess whether and to what extent the implementation of carbon control will increase environmental impacts upstream or downstream of the power plant.

Integrated environmental modelling and risk assessment

In addition to monitoring the data, it is equally important to predict the pollutant concentration at the receptor level under various meteorological conditions to strategize the mitigation solution. Frost (2014) used AERMOD to predict hourly SO2 concentrations for three different coal-fired power plants in southwest Indiana. Thus, during validation, overprediction during unstable environmental conditions and underprediction during low wind and stable environmental conditions were observed. Mokhtar et al. (2014) also used AERMOD to predict the SO2 and Hg concentration and then used the simulated data as an input for health risk assessment for a 700 MW coal power plant in Malaysia. Both non-carcinogenic pollutants (SO2, Hg) and carcinogenic trace elements (As, Cd) were assessed using a dose–response and risk characterization method. Levy et al. (2002) evaluated primary and secondary particulate matter impacts using CALPUFF across a Midwest grid based on nine power plants in Illinois. The study concluded that dispersion causes long-range transport of pollutants and may risk the health of many people even living away from the source.

Decision analysis for eco-friendly management of coal power plant

There are studies available to evaluate individual control technology or suggest the best technology selection concept (Zhang et al. 2019). There have not been efforts to develop an automated tool that can function as an integrated decision support environmental control system for power plants. For instance, Zhou et al. (2004) developed an integrated decision expert system using the Gaussian dispersion model and fuzzy relation model to select feasible air pollution control methods for coal power plants according to the desired removal efficiency. Cui et al. (2021) examined that in China between 2045 and 2055, the existing coal power plants would retire to achieve the 1.5 °C or below 2 °C climate goals by developing an integrated assessment model based on the Global Change Analysis Model (GCAM) and Multicriteria Decision Analysis Method (MCDA). A GIS-based integrated assessment system based on the GAINS (Greenhouse Gas- Air Pollution Interactions and Synergies) model can be used to investigate the efficiency of the electricity-dependent industries that help to reduce the coal-fired power plant fleet (Brown and Spiegel 2019). The efficient sectors could help to reduce air pollution from coal-fired power plants in those regions where electricity consumption is dominated by industry, such as Netherland, Germany, Poland, the USA, Australia, and South Africa (Brown and Spiegel 2019).

Circular economy approach

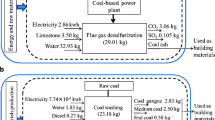

Lee et al. (2017) suggested a novel approach to shift from a linear model approach, i.e., one-way cradle to grave life cycle, toward a circular economy (CE) to improve resource efficiency, reduce the carbon footprints, and conserve the primary carbon resources. One of the ways to achieve a minimal CO2 footprint, next-generation gasification technology development is necessary. This new technology would need to facilitate complete carbon transformation in the syngas (i.e., optimize cold gas efficiency and carbon retention in chemical products), support resource recovery. For example, Fig. 7 shows a circular economy approach in a coal-fired power plant. The H2 as a syngas (produced during the gasification process (see Eq. 1)) can be used as hydrogen fuel cells in the transport sector (Leung et al. 2014). Hydrogen gas can also be transported to the chemical industry, where it is used for various processes, e.g., methanol and ammonia production, hydrogenation, hydrocracking, and hydrodesulfurization processes (Chen et al. 2020). The utilization of hydrogen gas in the energy system is growing much interest because of less greenhouse gas emissions and financial competitiveness (Leung et al. 2014). Another way CE could be achieved is to utilize the waste coal again as a feed (Cai et al. 2017). CFB power generating units fired with waste coal can clean up the waste piles, turning waste coal into valuable electricity. Similarly, CFB plants in the 50 MW size range sprang up in the waste coal (having 5000-6000BTU/lb heating value) areas of Pennsylvania, Ohio, and West Virginia (Adams et al. 2020). In addition, extra thermal heat generated during the electricity production process can also be utilized using the CHP process (Siddiqui and Dincer 2020). The coal fly ash (CFA) is produced during electricity production and collected by ESPs (Marinina et al. 2021). CFA mostly ranges from tan to black and very fine powder-like particles (Sanjuán et al. 2021). After collection, CFA is mixed with water and then dumped to the landfill sites, negatively impacting groundwater and surface water (Marinina et al. 2021). As CFA is produced in large quantities annually, proper dumping is an issue. For instance, in 2017, the accumulated amount of CFA in Russia was approximately 1.5 billion tons (Sanjuán et al. 2021). CFA can cost more than coal since it comprises various precious elements, such as three kilograms of uranium extracted from one ton of lignite from the US (Marinina et al. 2021). Under the umbrella of CE, CFA can be further processed to extract rare metals or utilize them in construction and building materials. In Europe, 1.936 million tons of CFA is used for cement production per annum (Sanjuán et al. 2021). During the desulfurization process, calcium sulphite is produced, which can be further oxidized to produce gypsum (Hunt and Sewell 2015). The gypsum is marketable because of its quality to utilize in wallboards and other such products it can somewhat offset the cost of the FGD installation (Lysack 2015).

Concluding remarks

This paper has presented a broad-ranging review of coal-fired power plants' impact on air quality, focusing on the North American region, China, and European countries. Coal-fired power plants are responsible for premature deaths, primarily in China, the USA, and EU countries. Lignite coal-based power plants emit more air pollutants than bituminous and anthracite coal. Although the decreasing trend of NOx and SO2 has been observed in many countries due to strict national levels and implementation of mitigation measurements, many power plants are emitting higher levels of PM2.5 and SO2. Among heavy metals, Hg is a significant issue regardless of power plant capacity and can deposit to nearby soil or aquatic system. Many recent physical technologies are discussed that could control PM2.5, SO2, NOx, and Hg, individually. However, coupling these techniques, such as SCR and WFGD, including some advanced processes such as activated coke and electrocatalytic oxidation, can remove multi pollutants simultaneously. These techniques could be used with CO2 removal techniques such as pre-combustion, oxyfuel, and post-combustion methods. However, significant investments are needed to roll out pre-combustion technologies widely. Also, oxyfuel combustion technologies limit their commercialization because of metal corrosion and high oxygen separation cost. Adsorption is the most effective post-combustion technique. It is observed that for each pollutant, coal type, adsorbent characteristics, and operating conditions vary for coal power plants. Undoubtedly, thermodynamic analysis is one of the ways to identify the losses and extra heat that could be utilized to achieve a more energy-efficient power plant, such as in the CHP technique and USC-PC boiler technology. In contrast to the future expectations towards cleaner fuel, the power generation in many countries currently still rely on coal. Therefore, adjustment to energy mix resources and renewable resources is a transition towards shifting away from coal. The applicability of renewable energy alternatives may depend on local availability. Power from solar, wind, marine is intermittent, and associated technologies are still more costly than conventional energy.

The environmental assessment is very useful in performing detailed financial and ecological planning for the sustainability of coal-fired power plants. Conclusively, the study emphasizes the significance of using the integrated approach methodology to evaluate environmental performance and associated risk. The best sustainable solution could be achieved through an integrated decision analysis approach, including life cycle assessment, the state-of-the-art environmental modelling, and multi-criteria analysis that would also help to offset the cost of air pollution control and carbon removal.

References

Adams D, Oh DH, Kim DW et al (2020) Prediction of SOx–NOx emission from a coal-fired CFB power plant with machine learning: plant data learned by deep neural network and least square support vector machine. J Clean Prod. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122310

Ades M, Adler R, Aldeco LS, Alejandra G (2019) State of the climate in 2018. Bull Am Meteorol Soc. 100

Akash AR, Rao AB, Chandel MK (2016) Prospects of implementing CO2 Capture and Sequestration (CCS) in the Proposed Supercritical Coal Power Plants in India. In: Energy Procedia. pp. 604–612

Amick P (2016) Case study: wabash river coal gasification repowering project, USA. In: Integrated Gasification Combined Cycle (IGCC) Technologies. Pp. 699–714

Avagyan A (2021) Theory of bioenergy accumulation and transformation: application to evolution, energy, sustainable development, climate change, manufacturing, agriculture, military activity and pandemic challenges. Athens J Sci 8:57–80

Ballabio C, Jiskra M, Osterwalder S et al (2021) A spatial assessment of mercury content in the European Union topsoil. Sci Total Environ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.144755

Bassano C, Deiana P, Vilardi G, Verdone N (2020) Modeling and economic evaluation of carbon capture and storage technologies integrated into synthetic natural gas and power-to-gas plants. Appl Energy. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2020.114590

Bhagiyalakshmi M, Yun LJ, Anuradha R, Jang HT (2010) Synthesis of chloropropylamine grafted mesoporous MCM-41, MCM-48 and SBA-15 from rice husk ash: Their application to CO2 chemisorption. J Porous Mater 17:475–484. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10934-009-9310-7

Borhan A, Yusup S, Lim JW, Show PL (2019) Characterization and modelling studies of activated carbon produced from rubber-seed shell using KOH for CO2 adsorption. Processes 7:855. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr7110855

Boruban C, Esenturk EN (2018) Activated carbon-supported CuO nanoparticles: a hybrid material for carbon dioxide adsorption. J Nanoparticle Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11051-018-4139-0

Boyle P (2002) ECO demonstrates the attractions of multi-pollutant control. In: Mod Power Syst. https://www.modernpowersystems.com/features/featureeco-demonstrates-the-attractions-of-multi-pollutant-control/. Accessed 3 Jul 2021

Boyle PD (2004) 50-MW commercial demonstration of a multi-pollutant control technology. In: Proceedings of the air and waste management association’s annual meeting and exhibition. pp. 1301–1317

Brown B, Spiegel SJ (2019) Coal, climate justice, and the cultural politics of energy transition. Glob Environ Polit 19:149–168. https://doi.org/10.1162/glep_a_00501

Buecker B (2006) Wet-limestone scrubbing fundamentals. Power Eng (Barrington, Illinois) 110:32–37

Bui M, Adjiman CS, Bardow A et al (2018) Carbon capture and storage (CCS): the way forward. Energy Environ Sci 11:1062–1176

Buonocore JJ, Salimifard P, Michanowicz DR, Allen JG (2021) A decade of the U.S. energy mix transitioning away from coal: historical reconstruction of the reductions in the public health burden of energy. Environ Res Lett. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/abe74c

Cai R, Ke X, Lyu J et al (2017) Progress of circulating fluidized bed combustion technology in China: a review. Clean Energy 1:36–49

Campbell E (2020) Germany is shutting down its coal industry for good, so far without sacking a single worker. In: Aust Broadcast Corp News (Section), Ultim Aust https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-02-18/australia-climate-how-germany-is-closing-down-its-coal-industry/11902884

Cao M, Zhao L, Xu D et al (2020) A carbon molecular sieve membrane-based reactive separation process for pre-combustion CO2 capture. J Memb Sci. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.memsci.2020.118028

Casey Z (2019) Chronic coal pollution - EU action on the Western Balkans will improve health and economies across Europe. HEAL, CAN Europe, Sandbag, CEE Bankwatch Network and Europe Beyond Coal

Cebrucean D, Cebrucean V, Ionel I (2020) Modeling and performance analysis of subcritical and supercritical coal-fired power plants with biomass co-firing and CO2 capture. Clean Technol Environ Policy 22:153–169. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10098-019-01774-1

Chao C, Deng Y, Dewil R et al (2021) Post-combustion carbon capture. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2020.110490

Chen Z, Wang Y, Zhang X (2020) Energy and exergy analyses of S-CO2 coal-fired power plant with reheating processes. Energy. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2020.118651

China Energy Portal (2021) 2019 detailed electricity statistics (Update of Jan 2021). https://chinaenergyportal.org/en/2019-detailed-electricity-statistics-update-of-jan-2021/

Cui RY, Hultman N, Cui D et al (2021) A plant-by-plant strategy for high-ambition coal power phaseout in China. Nat Commun. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-21786-0

Deng Y, Ansart R, Baeyens J, Zhang H (2019) Flue gas desulphurization in circulating fluidized beds. Energies. https://doi.org/10.3390/en12203908

EIA (2021) U.S. primary energy consumption by energy source, 2020. U.S. Energy Information Administration. https://www.eia.gov/energyexplained/us-energy-facts/. Accessed 11 Jul 2021

European data (2021) Coal is undermining Europe. In: Eur data Journal Netw https://www.europeandatajournalism.eu/eng/News/Data-news/Coal-is-undermining-Europe. Accessed 3 Jul 2021

Fan H, Zhang Z, Dong J, Xu W (2018) China’s R&D of advanced ultra-supercritical coal-fired power generation for addressing climate change. Therm Sci Eng Prog. 5

Fang M, Yi N, Di W, et al. (2020) Emission and control of flue gas pollutants in CO2 chemical absorption system—A review. Int J Greenh Gas Control 93

Feng H, Zhong W, Wu Y, Tong S (2014) Thermodynamic performance analysis and algorithm model of multi-pressure heat recovery steam generators (HRSG) based on heat exchangers layout. Energy Convers Manag 81:282–289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2014.02.060

Finkelman RB, Wolfe A, Hendryx MS (2021) The future environmental and health impacts of coal. Energy Geosci 2:99–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engeos.2020.11.001

Fraunhofer Institute for Solar Energy Systems ISE (2020) German Net Electricity Generation in First Half of 2020: Renewables Reach Record Share of 55.8 Percent. https://www.ise.fraunhofer.de/content/dam/ise/en/documents/press-releases/2020/1620_ISE_e_PR_Electricity Generation First Half 2020.pdf. Accessed 12 Jul 2021

Frost KD (2014) AERMOD performance evaluation for three coal-fired electrical generating units in Southwest Indiana. J Air Waste Manag Assoc 64:280–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/10962247.2013.858651

Government of Canada (2019) Electricity facts. https://www.nrcan.gc.ca/science-data/data-analysis/energy-data-analysis/energy-facts/electricity-facts/20068. Accessed 21 Jun 2021

Guo B, Wang Y, Shen X et al (2020) Study on CO2 capture characteristics and kinetics of modified potassium-based adsorbents. Materials (Basel) 13:877. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma13040877

Han X, Chen N, Yan J et al (2019) Thermodynamic analysis and life cycle assessment of supercritical pulverized coal-fired power plant integrated with No.0 feedwater pre-heater under partial loads. J Clean Prod 233:1106–1122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.06.159

Hunt G, Sewell M (2015) Utilizing dry sorbent injection technology to improve acid gas control. In: Air and Waste Management Association—International Conference on Thermal Treatment Technologies and Hazardous Waste Combustors 2015, IT3 2015. Pp. 144–156

IEA (2021) World Energy Statistics database: CO2 Emissions from Fuel Combustion: Overview. https://www.iea.org/reports/co2-emissions-from-fuel-combustion-overview. Accessed 26 Jun 2021

Jiang Y, Ahn S, Oh DH et al (2021) Optimization of separated overfire air to reduce NOX emissions under combustion stability for the retrofit of a 500 MW tangentially pulverized coal boiler. Fuel. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2020.119764

Jones M (2010) Electro Catalytic Oxidation (ECO®) Operation, Final Scientific/Technical Report

Kalita P, Nanibabu G, Vivek KP et al (2013) Design and performance evaluation of a novel biomass feeding system. J Sci Ind Res (india) 72:511–514

Koornneef J, van Keulen T, Faaij A, Turkenburg W (2008) Life cycle assessment of a pulverized coal power plant with post-combustion capture, transport and storage of CO2. Int J Greenh Gas Control. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijggc.2008.06.008

Korre A, Nie Z, Durucan S (2010) Life cycle modelling of fossil fuel power generation with post-combustion CO2 capture. Int J Greenh Gas Control. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijggc.2009.08.005

Kumar P, Faujdar E, Singh RK et al (2018) High CO2 absorption of O-carboxymethylchitosan synthesised from chitosan. Environ Chem Lett 16:1025–1031. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10311-018-0713-z

Kumar R, Mangalapuri R, Ahmadi MH et al (2020) The role of nanotechnology on post-combustion CO2 absorption in process industries. Int J Low-Carbon Technol 15:361–367. https://doi.org/10.1093/IJLCT/CTAA002

Lee RP, Keller F, Meyer B (2017) A concept to support the transformation from a linear to circular carbon economy: net zero emissions, resource efficiency and conservation through a coupling of the energy, chemical and waste management sectors. Clean Energy. https://doi.org/10.1093/ce/zkx004

Leung DYC, Caramanna G, Maroto-Valer MM (2014) An overview of current status of carbon dioxide capture and storage technologies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 39

Levy JI, Spengler JD, Hlinka D et al (2002) Using CALPUFF to evaluate the impacts of power plant emissions in Illinois: Model sensitivity and implications. Atmos Environ. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1352-2310(01)00493-9

Li L, Xie S, Zeng L et al (2015) Characteristics of volatile organic compounds and their role in ground-level ozone formation in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region, China. Atmos Environ 113:247–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2015.05.021

Li K, Feron PHM, Jones TW et al (2020a) Energy harvesting from amine-based CO2 capture: proof-of-concept based on mono-ethanolamine. Fuel. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2019.116661

Li Y, Zhang X, Huangfu L et al (2020b) The simultaneous removal of SO2 and NO from flue gas over activated coke in a multi-stage fluidized bed at low temperature. Fuel. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2020.117862

Liu K, Wang S, Wu Q et al (2018) A highly resolved mercury emission inventory of Chinese coal-fired power plants. Environ Sci Technol 52:2400–2408. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.7b06209

Lysack M (2015) Effective policy influencing and environmental advocacy: health, climate change, and phasing out coal. Int Soc Work 58:435–447. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020872814567485

Marinina O, Nevskaya M, Jonek-Kowalska I et al (2021) Recycling of coal fly ash as an example of an efficient circular economy: a stakeholder approach. Energies 14:3597. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14123597

Mokhtar MM, Hassim MH, Taib RM (2014) Health risk assessment of emissions from a coal-fired power plant using AERMOD modelling. Process Saf Environ Prot 92:476–485. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psep.2014.05.008

NASA (2021) Orbiting Carbon Observatory 2. https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/oco2/index.html. Accessed 6 Jul 2021

Nassar R, Hill TG, McLinden CA et al (2017) Quantifying CO2 emissions from individual power plants from space. Geophys Res Lett 44:10,045-10,053. https://doi.org/10.1002/2017GL074702

National Grid ESO UK (2021) Record-breaking 2020 becomes greenest year for Britain’s electricity. https://data.nationalgrideso.com/. Accessed 12 Jul 2021

NOAA (2021) Extremes. https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/extremes/. Accessed 29 Mar 2021

Osman AI, Hefny M, Abdel Maksoud MIA, et al. (2021) Recent advances in carbon capture storage and utilisation technologies: a review. Environ Chem Lett. 19

Peng Y, Yang Q, Wang L et al (2021) VOC emissions of coal-fired power plants in China based on life cycle assessment method. Fuel. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2021.120325

Rallo M, Lopez-Anton MA, Contreras ML, Maroto-Valer MM (2012) Mercury policy and regulations for coal-fired power plants. Environ Sci Pollut Res 19:1084–1096

Russell MC, Belle JH, Liu Y (2017) The impact of three recent coal-fired power plant closings on Pittsburgh air quality: a natural experiment. J Air Waste Manag Assoc 67:3–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/10962247.2016.1170738

Sanjuán MÁ, Suarez-Navarro JA, Argiz C, Estévez E (2021) Radiation dose calculation of fine and coarse coal fly ash used for building purposes. J Radioanal Nucl Chem 327:1045–1054. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10967-020-07578-8

Schreifels JJ, Wang S, Hao J (2012) Design and operational considerations for selective catalytic reduction technologies at coal-fired boilers. Front Energy 6:98–105

Siddiqui O, Dincer I (2020) A comparative life-cycle assessment of two cogeneration plants. Energy Technol. https://doi.org/10.1002/ente.201900425

Stanger R, Wall T, Spörl R et al (2015) Oxyfuel combustion for CO2 capture in power plants. Int J Greenh Gas Control 40:55–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijggc.2015.06.010