Abstract

Some mothers of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) present with maladaptive personality profiles (high neuroticism, low conscientiousness). The moderating effect of maternal personality traits on treatment outcomes for childhood ADHD has not been examined. We evaluate whether maternal neuroticism and conscientiousness moderated response in the Multimodal Treatment Study of Children with ADHD. This is one of the first studies of this type. In a randomized controlled trial (RCT), 579 children aged 7–10 (M = 8.5); 19.7% female; 60.8% White with combined-type ADHD were randomly assigned to systematic medication management (MedMgt) alone, comprehensive multicomponent behavioral treatment (Beh), their combination (Comb), or community comparison treatment-as-usual (CC). Latent class analysis and linear mixed effects models included 437 children whose biological mothers completed the NEO Five-Factor Inventory at baseline. A 3-class solution demonstrated best fit for the NEO: MN&MC = moderate neuroticism and conscientiousness (n = 284); HN&LC = high neuroticism, low conscientiousness (n = 83); LN&HC = low neuroticism, high conscientiousness (n = 70). Per parent-reported symptoms, children of mothers with HN&LC, but not LN&HC, had a significantly better response to Beh than to CC; children of mothers with MN&MC and LN&HC, but not HN&LC, responded better to Comb&MedMgt than to Beh&CC. Per teacher-reported symptoms, children of mothers with HN&LC, but not LN&HC, responded significantly better to Comb than to MedMgt. Children of mothers with high neuroticism and low conscientiousness benefited more from behavioral treatments (Beh vs. CC; Comb vs. MedMgt) than other children. Evaluation of maternal personality may aid in treatment selection for children with ADHD, though additional research on this topic is needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Despite strengths of existing evidence-based pharmacological and psychosocial treatments for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and disruptive behavior disorders, a substantial number of children fail to respond adequately. Approximately, one-third of children receiving well-managed FDA-approved medication for ADHD do not fully benefit even when augmented with behavioral treatment [1]. In addition, those who demonstrate good initial response may not show sustained benefit beyond 2 years [2, 3]. Thus, enhanced understanding of the relative efficacy of interventions for ADHD and disruptive behavior disorders is needed.

Family preferences, characteristics, and resources can influence the effects of interventions [4,5,6,7]. For example, some families may refuse medications or struggle to manage the demands of behavioral treatments amidst a chaotic home environment, psychosocial stressors, or parental psychopathology [6, 8,9,10]. Therefore, a “one size fits all” approach to treatment may lead to a mismatch between families and interventions [11, 12]. Attending to child and family characteristics in treatment selection may improve long-term outcomes [13], which at this point are suboptimal for many.

The identification of treatment moderators may offer one means of intervention tailoring and matching, by identifying subgroups for whom particular treatments are more or less effective [5, 14, 15]. Such an approach may ultimately enhance the relative efficacy of selected treatments for specific patient populations and facilitate the allocation of limited resources, thereby optimizing outcomes for children and families.

For instance, parental cognitions, attributions, and perceptions have been found to play a role in the therapist–caregiver relationship and influence treatment engagement, compliance, and decisions about continuation vs. termination of services [16,17,18]. Parental psychosocial factors and mental health issues may be particularly relevant to treatments for disruptive behavior disorders and ADHD in children, which require substantial parent engagement and oversight. For example, in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of interventions for disruptive behavior disorders in children, low marital adjustment, higher maternal depression, lower familial social class, presence of paternal substance use, and single-mother households were associated with enhanced response to evidence-based psychosocial treatments with parent- and/or child-focused components [5]. In addition, parent training was least effective for economically disadvantaged families, though these families seemed to benefit more from individual vs. group delivery format [8]. For adolescents with conduct problems, Multisystemic Therapy was more effective when fathers were involved in treatment [9]. Thus, parent/family psychosocial and psychopathological factors play an important role in the relative efficacy of interventions for disruptive behavior disorders [5, 8, 9].

Such parent/family variables are also relevant in the treatment of childhood ADHD. For example, high parental anxiety/depression predicted poor response to behavioral interventions in one RCT [6]. In the Multimodal Treatment Study of ADHD (MTA), higher parental education was associated with enhanced response of children’s ADHD symptoms to combination treatment (Comb—medication management and multicomponent behavioral treatment); children from blue-collar and lower SES homes similarly benefited most from Comb in terms of oppositional–aggressive symptoms [10]. Also in the MTA, parental depressive symptoms were associated with worse response to MedMgt, but not Comb [7]. The lack of behavioral support for parents in the MedMgt group may explain the apparent discrepancy with findings reported in Beauchaine et al. [5], who found maternal depression associated with a better response to behavioral intervention. In addition, ethnicity moderated outcomes in the MTA, such that ethnic minority families (African American, Latino) benefitted most from Comb [19]. Although exceptions to these findings exist [20], parental psychosocial factors and psychiatric symptoms are implicated in the phenomenology and treatment response among children with ADHD [6, 7, 10, 19].

Maladaptive parental personality traits may also play a role in response to childhood ADHD treatments. Certain maladaptive personality dimensions have been found to both predict and moderate treatment response for childhood problems other than ADHD. One study found that elevated Cluster B personality disorder (antisocial, borderline, narcissistic, histrionic) symptoms in parents predicted poor response across treatment conditions in a RCT for children with depressive and bipolar disorders [21]. In a RCT of the Oregon model of Parent Management Training for conduct problems, parent antisocial characteristics moderated the effect on coercive but not positive parenting practices [22]. Thus, although not as commonly studied, parental personality traits appear to be implicated in intervention response for childhood psychiatric problems.

Indeed, it is well known that personality traits affect parenting practices. Maladaptive personality profiles, such as high levels of neuroticism (anxious or nervous; prone to stress, guilt, frustration and anger) and low levels of conscientiousness (reliable, rule-abiding, organized, achievement driven) are associated with ineffective parenting (e.g., high levels of negative affectivity toward children) [23,24,25,26,27,28,29]. Research has also documented an association between personality traits and coping styles, with conscientiousness predicting adaptive coping (e.g., problem solving), and neuroticism predicting maladaptive coping (e.g., wishful thinking) [30]. Thus, high maternal neuroticism and low maternal conscientiousness in particular may perpetuate problematic functioning in relation to both the individual and family, with potentially important implications for children’s treatment outcomes.

In sum, parental personality traits may be important to consider in treatment selection for childhood ADHD. Indeed, prior research suggests that mothers of children with ADHD present with high levels of neuroticism and low levels of conscientiousness and agreeableness [31,32,33]. In addition, the idea of a core temperamental propensity to ADHD is corroborated by inattention–disorganization in young adults with low levels of conscientiousness and high neuroticism [34].

The current study examined the moderating effect of maternal personality traits on treatment response in the MTA. Based on prior literature documenting high neuroticism and low conscientiousness in mothers of children with ADHD [31,32,33], we focused on these personality dimensions. Individuals with high neuroticism present with increased anxiety or nervousness, and are prone to stress, guilt, frustration, and anger, while individuals who are highly conscientious tend to be reliable, rule-abiding, and achievement-driven [25, 35]. We expected these traits to moderate treatment response, given their association with a broad range of variables that could influence the efficacy of interventions for children with ADHD.

We hypothesized the following: first, children of mothers with high levels of neuroticism and low levels of conscientiousness would demonstrate better response to treatments with structured behavioral components (e.g., Beh—intensive behavioral treatment) than those without such structured components (e.g., CC—community comparison treatment-as-usual), because these treatments specifically target parenting practices that may be problematic for mothers with this personality profile. Second, we expected that children with mothers possessing the opposite personality profile (low neuroticism and high conscientiousness) would demonstrate better response to medication (MedMgt) vs. Beh and CC, as these parents may already possess adequate parenting/coping skills, not requiring added supports.

Methods

Sample and procedures

This study concerns a secondary analysis of the MTA [36,37,38]. The sample in the original study included 579 children aged 7–10 (M = 8.5, SD = 0.8; 19.7% female; 60.8% White) meeting DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for ADHD, combined type. Across six sites, children were randomly assigned in equal proportions to medication management (MedMgt), intensive behavioral treatment (Beh), their combination (Comb), or community comparison treatment-as-usual (CC) for 14 months. MedMgt consisted of a 1-month double-blind titration with methylphenidate [progressing to an open titration with other medications (e.g., d-amphetamine, pemoline, imipramine) if methylphenidate was not better than placebo], followed by maintenance at the optimal dose. Beh consisted of intense, multicomponent individual and group parent training; teacher consultation; a child-focused 8-week full-time summer treatment program with morning academic work and afternoon sports and social skills; and a 12-week half-time classroom behavioral specialist (a summer treatment counselor) to integrate the summer gains into the classroom. Comb integrated the MedMgt and Beh strategies. CC consisted of community treatment of the parents’ choosing; 2/3 obtained medication similar to that given by the MTA but not as carefully managed and at lower doses. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics across treatment conditions were generally negligible and non-significant.

Participants for the current secondary analysis included 437 children whose biological mothers completed the NEO Five-Factor Inventory [39].

Study procedures were overseen by each site’s institutional review board, and written informed consent and assent were obtained from parents and children, respectively. Additional details about sampling and procedures in the MTA are described elsewhere [36, 37].

Measures

A comprehensive description of all assessments in the MTA has been outlined previously [40].

Children’s ADHD and disruptive behavior symptom severity was measured at baseline and 3, 9, and 14 months via the parent- and the teacher-reported Swanson, Nolan, and Pelham (SNAP) rating scale [41]. The SNAP includes inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity subscales and has good internal consistency, inter-rater reliability (between teachers and parents), and predictive validity [41, 42]. It also included ratings of oppositional–defiant disorder (ODD) symptoms on the same 0–3 metric. Because the MTA behavioral treatment addressed both ADHD and disruptive behavior symptoms, we included in our outcome variable both the 18 ADHD and the 8 ODD symptoms, using the SNAP item mean. Children’s diagnostic status (ODD, anxiety) were determined through formal initial diagnosis using DISC-IIIR.

Biological mothers’ mental health status was determined through report of primary informant (89% of informants were biological mothers) at study entry. Questions assessed whether the biological mother had mental health and nervous problems and type of treatment received, if any.

Biological mothers’ personality traits were measured at 3 months via the NEO Five-Factor Inventory [39]. This study focused specifically on neuroticism and conscientiousness. Example items are: (1) neuroticism, “I often feel tense or jittery,” and (2) conscientiousness, “When I make a commitment, I can always be counted on to follow through.” The NEO Five-Factor Inventory has strong psychometric properties [43].

Biological mothers’ depressive symptoms were measured at baseline via the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) [44]. The BDI internal consistency, test–retest reliability, and convergent validity have been adequately demonstrated [44]. Maternal depression was included, because a previous qualitative ROC analysis [7] found it to be a significant moderator of treatment response in this sample. Biological mothers’ ADHD-related symptom dimensions were measured at baseline via the Conners’ Adult ADHD Rating Scales (CAARS) [45]. The CAARS has good internal reliability, test–retest reliability, sensitivity, and specificity [46]. Consistent with other MTA analyses, empirically derived factors of inattention/cognitive problems, hyperactivity/restlessness, and impulsivity/emotional lability were examined [47].

Negative/ineffective discipline was measured using Hinshaw et al. [48] second order factor (Chronbach α = 0.83), derived from the Alabama Parenting Questionnaire and the Parent Child Relationship Questionnaire first order factors.

Statistical analyses

First, latent class analysis (LCA via Mplus Version 8.1) was used to estimate subgroups of mothers with different combinations of NEO neuroticism and conscientiousness scale levels. LCA identifies latent subgroups of mothers using their pattern of responses to NEO subscales [49, 50]. BIC, entropy, parsimony, and substantive interpretability guided model selection [50].

Second, we evaluated if there were differences in demographics, treatment allocation, and child and maternal clinical characteristics between latent classes. For example, we tested if there were differences in the number of children with comorbid anxiety disorder, a factor that has been shown to predict treatment responses in previous studies [5, 51]. We also evaluated if there were differences in mothers’ ADHD-related symptom dimensions and negative/ineffective discipline between classes. We conducted these analyses in light of the idea that personality traits affect parenting practices, and because of the possibility of having a core temperamental propensity to ADHD related with a certain combination of personality traits [35].

Third, linear mixed effects modeling (LME via SAS version 9.4) was used to test the moderating effect of the resulting maternal personality latent classes on children’s ADHD symptom severity, using longitudinal SNAP measurements at baseline, 3, 9 and 14 months. Models included fixed effects for time (log of the number of days since randomization in MTA [38]), treatment, and NEO latent classes; children’s ADHD symptom severity (measured via parent- and teacher-reported SNAP) as the dependent variable; and a subject-specific random intercept and slope. Moderation was tested using the three-way interaction of time × NEO latent class × treatment, with treatment operationalized using a set of previously developed orthogonal contrasts: (1) MedMgt&Comb vs. CC&Beh; (2) MedMgt vs. Comb; (3) and Beh vs. CC [2, 52]. For NEO latent class, we generated dummy variables. As a sensitivity analysis, we expanded the previous model incorporating maternal depression and self-report history of mental/nervous problems as covariates.

Results

Latent class analysis

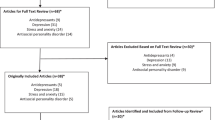

Comparing the fit of latent class models for 1–4 classes, a 3-class solution demonstrated best fit for neuroticism and conscientiousness, with a satisfactory proportion of mothers per class (Table 1).

Figure 1 displays the three NEO neuroticism and conscientiousness classes. Mothers in the first class had moderate levels of neuroticism and conscientiousness (MN&MC, n = 284, 65%). Mothers in the second class had a high level of neuroticism and a low level of conscientiousness (HN&LC, n = 83, 19%). Mothers in the third class had a low level of neuroticism and a high level of conscientiousness (LN&HC, n = 70, 16%).

Table 2 presents demographic, clinical information, and treatment allocation for children of mothers in the empirically derived classes. There were significant differences in depression and ADHD-related symptom dimensions, such that mothers in the HN&LC class reported a greater number of depressive and ADHD symptoms than mothers in other classes. The HN&LC class also self-reported significantly more mental/nervous problems at baseline than mothers in the MN&MC and LN&HC classes. The HN&LC (and MN&MC) classes also showed significantly higher scores of negative/ineffective discipline than LN&HC.

Moderation analysis

Parent report

Two significant three-way interactions emerged regarding SNAP parent report. The largest effect occurred when comparing the treatment response between Beh and CC (b = − 0.12, se = 0.05, p = 0.009). Children of mothers in the HN&LC class who received Beh demonstrated a significantly better response (simple slope b = − 0.31, se = 0.04, CI = − 0.39 to − 0.24) than children with mothers in the same class who received CC (simple slope b = − 0.18, se = 0.04, CI = − 0.26 to − 0.11) (Fig. 2a). In contrast, children with mothers in the LN&HC class had a non-significant differential treatment response in the opposite direction: (Beh simple slope b = − 0.24, se = 0.04, CI = − 0.31 to − 0.16 and CC simple slope b = − 0.35, se = 0.05, CI = − 0.45 to − 0.26) (Table 3; Fig. 2).

Maternal neuroticism and conscientiousness as moderators of treatment response. a Shows how children of mothers in HN&LC class receiving Beh (red line) demonstrated a better treatment response than children with mothers in the same class who received CC (orange line). b Shows no difference in children’s treatment response to Beh or CC with mothers in the LN&HC. HN&LC high neuroticism and low conscientiousness, LN&HC low neuroticism and high conscientiousness, Beh behavioral, CC community comparison

The other significant effect on parent-rated symptoms (b = − 0.05, se = 0.03, p = 0.04) reflected the main MTA outcome finding for the bulk of the sample [38] for all but the HN&LC group. That is, Comb&MedMgt was better than Beh&CC for MN&MC and LN&HC, but not for HN&LC who did better with Beh&CC (Fig. 3). Children with mothers in the MN&MC class (over half of the sample) who received Comb&MedMgt demonstrated better treatment response (simple slope b = − 0.37, se = 0.02, CI = − 0.40 to − 0.33) than children with mothers in the same class who received Beh&CC (simple slope b = − 0.15, se = 0.02, CI = − 0.18 to − 0.12). Similarly, children with mothers in the LN&HC class responded better to Comb&MedMgt (simple slope b = − 0.35, se = 0.03, CI = − 0.41 to − 0.29) than to Beh&CC (simple slope b = − 0.24, se = 0.04, CI = − 0.31 to − 0.17).

Maternal neuroticism and conscientiousness as moderators of treatment response. LN&HC low neuroticism and high conscientiousness, MN&MC moderate neuroticism and moderate conscientiousness, HN&LC high neuroticism and low conscientiousness, Comb combined, MedMgt medication management, Beh behavioral, CC community comparison. The three graphs above show a decreasing improvement with Comb&MdMgt (systematic medication, blue line) as you go from LN&HC to HN&LC (left to right). LN&HC did better with Beh&CC (gray line) than MN&MC, while HN&LC did less well with Comb&MedMgt, the two arms with systematic medication

Teacher report

One significant three-way interaction emerged for SNAP teacher report (b = − 0.13, se = 0.06, p = 0.02). Children with mothers in the HN&LC class who received Comb demonstrated better treatment response (simple slope b = − 0.39, se = 0.05, CI = − 0.49 to − 0.30) than children with mothers in the same class who received MedMgt (simple slope b = − 0.22, se = 0.05, CI = − 0.31 to − 0.13). The difference between these two treatments was non-significant in the opposite direction for children with mothers in the LN&HC class (Comb simple slope b = − 0.31, se = 0.05, CI = − 0.41 to − 0.22; MedMgt simple slope b = − 0.40, se = 0.06, CI = − 0.48 to − 0.30) (Table 3; Fig. 4).

Maternal neuroticism and conscientiousness as moderators of treatment response. a Shows how children of mothers in HN&LC class receiving Combined (green line) demonstrated a better treatment response than children with mothers in the same class who received MedMgt (yellow line). b Shows no difference in children’s treatment response to Comb or MedMgt with mothers in the LN&HC. HN&LC high neuroticism and low conscientiousness, LN&HC low neuroticism and high conscientiousness, Comb combined, MedMgt medication management

Sensitivity analysis

Two sensitivity analysis models evaluated the robustness of aforementioned findings, by covarying maternal depression and self-report history of mental/nervous problems. When using SNAP parent report as the dependent variable (n = 393), the time × HN&LC × Beh vs. CC and time × MN&MC × Comb&MedMgt vs. Beh&CC interactions remained significant (b = − 0.11, se = 05, p = 0.03 and b = − 0.06, se = 03, p = 0.02, respectively). Additionally, the time × HN&LC × Comb vs. MedMgt interaction emerged as significant in this model (b = − 0.10, se = 05, p = 0.03). When using SNAP teacher report as the dependent variable (n = 392), time × HN&LC × Comb vs. MedMgt interaction remained the sole significant three-way interaction (b = − 0.13, se = 06, p = 0.03), as in the original model.

Discussion

This is one of the first studies to examine the moderating effect of maternal personality traits on treatment response for children with ADHD. Mothers presented with different levels of neuroticism and conscientiousness, and mothers with high neuroticism and low conscientiousness (n = 83/437) reported greater depressive symptoms, ADHD symptoms, and mental/nervous problems than mothers with moderate or low neuroticism and moderate or high conscientiousness. Moreover, levels of neuroticism and conscientiousness moderated treatment effects. Specifically, children with mothers in the HN&LC class who received Beh demonstrated better response on SNAP parent report than children with mothers in the same class who received CC, whereas treatment response trended (nonsignificantly) in the opposite direction for children with mothers in the LN&HC class. Comparing treatments involving medication, Comb&MedMgt were predictably better than Beh&CC for children with mothers in the MN&MC or LN&HC class, as was the case for the whole MTA sample [1, 36]. However, this well-established MTA finding was not found for the HN&LC class. Finally, for SNAP teacher report, children with mothers in the HN&LC class who received Comb demonstrated better treatment response than children with mothers in the same class who received MedMgt, whereas the difference between the two treatments was actually nonsignificant in the opposite direction for children with LN&HC mothers. Importantly, results remained significant after adjusting for maternal depression and mental/nervous problems. These findings for both parent- and teacher-rated ADHD and oppositional–defiant symptom severity paints a picture of maternal high neuroticism and low conscientiousness predicting a better response to behavioral treatment and relatively lesser response to medication.

The finding that mothers in the HN&LC class reported higher depression, and ADHD symptoms measured with the CAARS, mental/nervous problems, and negative/ineffective discipline is in line with prior research documenting that parents of children with ADHD present with high rates of depression, ADHD symptoms, and parenting stress [31, 53, 54], in addition to increased neuroticism and decreased conscientiousness [31,32,33].

In terms of moderator findings, the effect on teacher ratings suggests a real moderation of treatment response, not just an effect of parent personality on parent ratings. Collectively, results suggest that children of mothers with high neuroticism and low conscientiousness may benefit most from structured behavioral treatments, either alone or added to medication. High neuroticism and low conscientiousness are associated with poor coping [30] and ineffective parenting practices [23,24,25,26,27,28,29]. Because behavioral treatments specifically target these deficits, children of personality-impaired mothers may demonstrate the largest gains in response to newly implemented effective parenting strategies. In contrast, mothers with more adaptive personality profiles (low neuroticism and high conscientiousness) may have enjoyed effective parenting and coping abilities from the start, and thus did not benefit as much from targeted, structured interventions for these skills. Indeed, improvements in negative/ineffective parental discipline mediated outcomes in the MTA [48]. Insofar as anxious, neurotic mothers tend to have anxious children, the finding that children of HN&LC mothers respond relatively better to behavioral treatment than children of LN&HC mothers is consistent with prior MTA findings documenting that children with comorbid anxiety responded relatively better to behavioral treatment [38]. In addition, these results are consistent with structured evidence-based treatments tending to be most effective for children and families with the greatest impairment [21, 22]. Thus, parental assessment prior to treatment initiation for childhood mental health problems, including ADHD, may help inform the most effective and optimal interventions.

An alternate possible explanation arises from the intensive and multicomponent nature of the MTA behavioral intervention, incorporating not only individual and group parent training, but also teacher consultation, a child-directed 8-week full-time summer treatment program, and a 12-week half-time classroom paraprofessional behavioral aide. It is therefore possible that the children of more impaired mothers benefitted to a greater extent from the consistency and support of extensive “wrap-around” services they received and not from parental changes per se. Further research is required to determine the mechanism through which behavioral treatments and maternal personality traits interact to facilitate improvement in children’s ADHD symptoms.

Findings should also be viewed within the context of another significant parental moderator of MTA treatment response: parental depression. Specifically, baseline parental depressive symptoms were associated with worse response in MedMgt and Comb [7]. In these analyses, Owens et al. suggested that parental depressive symptoms may have interfered with children’s receipt of medication (inconsistency with doctor visits, filling prescriptions, administering medications), therefore thwarting the potential therapeutic effect of such pharmacologic intervention. In contrast, because parents received added supports and training via behavioral treatment, this was thought to have mitigated the negative effect of parental depression on children’s ADHD symptoms [7]. These prior findings are in line with current results, which similarly suggest that behavioral interventions may be most effective for mothers with coping problems. Importantly, because personality traits represent more stable and enduring deficits than waxing/waning psychopathology (such as depression), personality may be more useful to measure and consider when selecting treatment. Further research is needed to clarify the relation between maternal personality traits, depression, and children’s ADHD symptoms, as depressive symptoms may mediate the relationship between maternal personality and treatment response, or vice versa.

It is interesting that the superiority of behavioral treatment for children of HN&LC mothers relative to children of LN&HC mothers was manifested in different orthogonal contrasts for parent and teacher ratings. For parent ratings, it manifested as significant superiority of behavioral treatment alone over routine community care, which at that time was mainly suboptimal medication; this was the “behavioral substitution effect”. But for teacher ratings, in the context of medication dramatically impacting classroom performance, it manifests as superiority of combination over medication alone—the “behavioral additive effect”. At the very least, findings highlight convergence of moderation findings between parental depression and maternal personality, though with some nuances.

Limitations

Despite the strengths of this study, findings should be interpreted within the context of limitations. First, analyses were restricted to personality traits of biological mothers, to reduce potential confounds. However, personality traits of other caregivers may also influence treatment response. Second, these personality traits were measured 3 months after baseline. This is not an optimal situation to test moderators. Third, there was limited variability in conscientiousness vs. neuroticism, which may have limited power to detect significant differences. Families choosing to enroll in an RCT in general may be more compliant and conscientious than families who opt out of RCTs. Fourth, analyses focused on the personality traits of neuroticism and conscientiousness, given prior literature documenting this profile in mothers of children with ADHD [31,32,33], but other personality dimensions may also influence treatment outcomes such as novelty seeking [55]. Fifth, biological mothers’ mental health status was based on self-report. Sixth, analyses were restricted only to participants whose biological mothers completed the NEO Five-Factor Inventory. Seventh, the generalizability of these findings may be limited by the intensity of the MTA behavioral treatment, which consisted of 35 parent training sessions, 10 teacher consultations, an 8-week-all-day summer treatment program, and 12 weeks of a half-time paraprofessional aid in the classroom. Less comprehensive behavioral programs may not show the same results. Finally, although it is a strength that moderation findings were maintained when adjusting for maternal depression and mental/nervous problems, it is possible that other unmeasured parent variables moderated treatment response or at least partially accounted for the relationship observed in the current study between maternal personality and treatment response. For example, prior research has identified numerous other parental factors that can influence children’s treatment response, including: ethnicity, marital adjustment, social class, education level, family composition, paternal involvement in treatment, internalizing symptoms, substance use, and cluster B personality disorder symptoms [5,6,7,8,9,10, 19, 21, 22].

Thus, future research should further explore: (1) personality in a variety of different caregivers; (2) if dyadic personality profiles (between two caregivers or between caregiver and child) have a stronger impact on treatment response; (3) other personality dimension; (4) the impact of child comorbid anxiety; and (5) a wider variety of possible parent/family predictors and moderators.

Clinical implications

Children with ADHD who have mothers with more impaired personality profiles (high neuroticism and low conscientiousness) appear to benefit most from the structured MTA behavioral interventions (by targeting maladaptive parenting and coping via parent training, and/or by extensive wrap-around services including teacher consultation, summer treatment program, and a classroom behavioral aide). In contrast, children of mothers with more adaptive personality profiles (moderate/low neuroticism and moderate/high conscientiousness) may experience adequate improvement in ADHD symptoms with pharmacotherapy alone, because these mothers are likely to be more skilled and/or have less room for growth. Thus, maternal personality could inform treatment planning for childhood ADHD (e.g., more impaired mothers may require behavioral treatments), though additional research is needed and other moderating factors must be considered. Nevertheless, maternal personality profiles may be important targets in future intervention development work.

References

Swanson JM, Kraemer HC, Hinshaw SP, Arnold LE, Conners CK, Abikoff HB, Clevenger W, Davies M, Elliott GR, Greenhill LL, Hechtman L, Hoza B, Jensen PS, March JS, Newcorn JH, Owens EB, Pelham WE, Schiller E, Severe JB, Simpson S, Vitiello B, Wells K, Wigal T, Wu M (2001) Clinical relevance of the primary findings of the MTA: success rates based on severity of ADHD and ODD symptoms at the end of treatment. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 40(2):168–179. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200102000-00011

Molina BSG, Hinshaw SP, Swanson JM, Arnold LE, Vitiello B, Jensen PS, Epstein JN, Hoza B, Hechtman L, Abikoff HB, Elliott GR, Greenhill LL, Newcorn JH, Wells KC, Wigal T, Gibbons RD, Hur K, Houck PR, Grp MC (2009) The MTA at 8 years: prospective follow-up of children treated for combined-type ADHD in a multisite study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 48(5):484–500. https://doi.org/10.1097/CHI.0b013e31819c23d0

Jensen PS, Arnold LE, Swanson JM, Vitiello B, Abikoff HB, Greenhill LL, Hechtman L, Hinshaw SP, Pelham WE, Wells KC, Conners K, Elliott GF, Epstein JN, Hoza B, March JS, Molina BSG, Newcorn JYH, Severe JB, Wigal T, Gibbons RD, Hur K (2007) 3-year follow-up of the NIMH MTA study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 46(8):989–1002. https://doi.org/10.1097/chi.0b013e3180686d48

Hinshaw SP (2007) Moderators and mediators of treatment outcome for youth with ADHD: understanding for whom and how interventions work. Ambul Pediatr 7(1 Suppl):91–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ambp.2006.04.012

Beauchaine TP, Webster-Stratton C, Reid MJ (2005) Mediators, moderators, and predictors of 1-year outcomes among children treated for early-onset conduct problems: a latent growth curve analysis. J Consult Clin Psychol 73(3):371–388. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006x.73.3.371

Owens EB, Hinshaw SP, McBurnett K, Pfiffner L (2016) Predictors of response to behavioral treatments among children with ADHD-inattentive type. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 47:S219–S232. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2016.1228461

Owens EB, Hinshaw SP, Kraemer HC, Arnold LE, Abikoff HB, Cantwell DP, Conners CK, Elliott G, Greenhill LL, Hechtman L, Hoza B, Jensen PS, March JS, Newcorn JH, Pelham WE, Severe JB, Swanson JM, Vitiello B, Wells KC, Wigal T (2003) Which treatment for whom for ADHD? Moderators of treatment response in the MTA. J Consult Clin Psychol 71(3):540–552. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006x.71.3.540

Lundahl B, Risser HJ, Lovejoy MC (2006) A meta-analysis of parent training: moderators and follow-up effects. Clin Psychol Rev 26(1):86–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2005.07.004

Gervan S, Granic I, Solomon T, Blokland K, Ferguson B (2012) Paternal involvement in multisystemic therapy: effects on adolescent outcomes and maternal depression. J Adolesc 35(3):743–751. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.10.009

Rieppi R, Greenhill LL, Ford RE, Chuang S, Wu M, Davies M, Abikoff HB, Arnold LE, Conners CK, Elliott GR, Hechtman L, Hinshaw SP, Hoza B, Jensen PS, Kraemer HC, March JS, Newcorn JH, Pelham WE, Severe JB, Swanson JM, Vitiello B, Wells KC, Wigal T (2002) Socioeconomic status as a moderator of ADHD treatment outcomes. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 41(3):269–277. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200203000-00006

Spetie L, Arnold LE (2007) Ethical issues in child psychopharmacology research and practice: emphasis on preschoolers. Psychopharmacology 191(1):15–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-006-0685-8

Hechtman L, Swanson JM, Sibley MH, Stehli A, Owens EB, Mitchell JT, Arnold LE, Molina BS, Hinshaw SP, Jensen PS, Abikoff HB, Perez Algorta G, Howard AL, Hoza B, Etcovitch J, Houssais S, Lakes KD, Nichols JQ (2016) Functional adult outcomes 16 years after childhood diagnosis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: MTA results. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 55(11):945–952. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2016.07.774

Gray JAM (2013) The art of medicine: the shift to personalised and population medicine. Lancet 382(9888):200–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61590-1

Kraemer HC, Wilson GT, Fairburn CG, Agras WS (2002) Mediators and moderators of treatment effects in randomized clinical trials. Arch Gen Psychiatry 59(10):877–883

La Greca AM, Silverman WK, Lochman JE (2009) Moving beyond efficacy and effectiveness in child and adolescent intervention research. J Consult Clin Psychol 77(3):373–382. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015954

Young AS, Horwitz S, Findling RL, Youngstrom EA, Arnold LE, Fristad MA (2016) Parents’ perceived treatment match and treatment retention over 12 months among youths in the LAMS study. Psychiatr Serv (Wash DC) 67(3):310–315. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201400553

Morrissey-Kane E, Prinz RJ (1999) Engagement in child and adolescent treatment: the role of parental cognitions and attributions. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 2(3):183–198

Haine-Schlagel R, Walsh NE (2015) A review of parent participation engagement in child and family mental health treatment. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 18(2):133–150. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-015-0182-x

Arnold LE, Elliot M, Sachs L, Bird H, Kraemer HC, Wells KC, Abikoff HB, Comarda A, Conners CK, Elliott GR, Greenhill LL, Hechtman L, Hindshaw SP, Hoza B, Jensen PS, March JS, Newcorn JH, Pelham WE, Severe JB, Swanson JM, Vitiello B, Wigal T (2003) Effects of ethnicity on treatment attendance, stimulant response/dose, and 14-month outcome in ADHD. J Consult Clin Psychol 71(4):713–727. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006x.71.4.713

van den Hoofdakker BJ, Nauta MH, van der Veen-Mulders L, Sytema S, Emmelkamp PMG, Minderaa RB, Hoekstra PJ (2010) Behavioral parent training as an adjunct to routine care in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: moderators of treatment response. J Pediatr Psychol 35(3):317–326. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsp060

MacPherson HA, Algorta GP, Mendenhall AN, Fields BW, Fristad MA (2014) Predictors and moderators in the randomized trial of multifamily psychoeducational psychotherapy for childhood mood disorders. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 43(3):459–472. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2013.807735

Wachlarowicz M, Snyder J, Low S, Forgatch M, Degarmo D (2012) The moderating effects of parent antisocial characteristics on the effects of Parent Management Training-Oregon (PMTO). Prev Sci 13(3):229–240. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-011-0262-1

Puff J, Renk K (2016) Mothers’ temperament and personality: their relationship to parenting behaviors, locus of control, and young children’s functioning. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 47(5):799–818. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-015-0613-4

Florange JG, Herpertz SC (2019) Parenting in patients with borderline personality disorder, sequelae for the offspring and approaches to treatment and prevention. Curr Psychiatry Rep 21(2):9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-019-0996-1

McCabe JE (2014) Maternal personality and psychopathology as determinants of parenting behavior: a quantitative integration of two parenting literatures. Psychol Bull 140(3):722–750. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034835

Kochanska G, Kim S, Koenig Nordling J (2012) Challenging circumstances moderate the links between mothers’ personality traits and their parenting in low-income families with young children. J Pers Soc Psychol 103(6):1040–1049. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030386

Prinzie P, Stams GJ, Dekovic M, Reijntjes AH, Belsky J (2009) The relations between parents’ Big Five personality factors and parenting: a meta-analytic review. J Pers Soc Psychol 97(2):351–362. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015823

Bornstein MH, Hahn CS, Haynes OM (2011) Maternal personality, parenting cognitions, and parenting practices. Dev Psychol 47(3):658–675. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023181

Belsky J (1984) The determinants of parenting: a process model. Child Dev 55(1):83–96

Connor-Smith JK, Flachsbart C (2007) Relations between personality and coping: a meta-analysis. J Pers Soc Psychol 93(6):1080–1107. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.93.6.1080

Perez Algorta G, Kragh CA, Arnold LE, Molina BSG, Hinshaw SP, Swanson JM, Hechtman L, Copley LM, Lowe M, Jensen PS (2018) Maternal ADHD symptoms, personality, and parenting stress: differences between mothers of children with ADHD and mothers of comparison children. J Atten Disord 22(13):1266–1277. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054714561290

Weinstein CS, Apfel RJ, Weinstein SR (1998) Description of mothers with ADHD with children with ADHD. Psychiatry-Interpers Biol Process 61(1):12–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/00332747.1998.11024815

Steinhausen HC, Gollner J, Brandeis D, Muller UC, Valko L, Drechsler R (2013) Psychopathology and personality in parents of children with ADHD. J Atten Disord 17(1):38–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054711427562

Nigg JT, John OP, Blaskey LG, Huang-Pollock CL, Willcutt EG, Hinshaw SP, Pennington B (2002) Big five dimensions and ADHD symptoms: links between personality traits and clinical symptoms. J Pers Soc Psychol 83(2):451–469. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.83.2.451

McCrae RR, John OP (1992) An introduction to the five-factor model and its applications. J Pers 60(2):175–215

Arnold LE, Abikoff HB, Cantwell DP, Conners CK, Elliott G, Greenhill LL, Hechtman L, Hinshaw SP, Hoza B, Jensen PS, Kraemer HC, March JS, Newcorn JH, Pelham WE, Richters JE, Schiller E, Severe JB, Swanson JM, Vereen D, Wells KC (1997) National Institute of Mental Health Collaborative Multimodal Treatment Study of children with ADHD (the MTA)—design challenges and choices. Arch Gen Psychiatry 54(9):865–870

Arnold LE, Abikoff HB, Cantwell DP, Conners CK, Elliott GR, Greenhill LL, Hechtman L, Hinshaw SP, Hoza B, Jensen PS, Kraemer HC, March JS, Newcorn JH, Pelham WE, Richters JE, Schiller E, Severe JB, Swanson JM, Vereen D, Wells KC (1997) NIMH collaborative multimodal treatment study of children with ADHD (MTA): design, methodology, and protocol evolution. J Atten Disord 2(3):141–158. https://doi.org/10.1177/108705479700200301

Group TMC (1999) A 14-month randomized clinical trial of treatment strategies for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. The MTA Cooperative Group. Multimodal treatment study of children with ADHD. Arch Gen Psychiatry 56(12):1073–1086

Costa PT Jr, McCrae RR (1992) The five-factor model of personality and its relevance to personality disorders. J Pers Disord 6(4):343–359

Hinshaw SP, March JS, Abikoff H, Arnold LE, Cantwell DP, Conners CK, Elliott GR, Halperin J, Greenhill LL, Hechtman LT, Hoza B, Jensen PS, Newcorn JH, McBurnett K, Pelham WE, Richters JE, Severe JB, Schiller E, Swanson J, Vereen D, Wells K, Wigal T (1997) Comprehensive assessment of childhood attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in the context of a multisite, multimodal clinical trial. J Atten Disord 1(4):217–234. https://doi.org/10.1177/108705479700100403

Swanson JM (1992) School-based assessments and interventions for ADD students. KC publishing. ISBN 0963525506, 9780963525505

Bussing R, Fernandez M, Harwood M, Hou W, Garvan CW, Eyberg SM, Swanson JM (2008) Parent and teacher SNAP-IV ratings of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms—psychometric properties and normative ratings from a school district sample. Assessment 15(3):317–328. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191107313888

McCrae RR, Kurtz JE, Yamagata S, Terracciano A (2011) Internal consistency, retest reliability, and their implications for personality scale validity. Pers Soc Psychol Rev 15(1):28–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868310366253

Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J (1961) An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 4:561–571

Conners CK, Erhardt D, Sparrow E (1999) Conners’ adult ADHD rating scales (CAARS): technical manual. Multi-Health Systems, North Tonawanda

Erhardt D, Epstein JN, Conners CK, Parker JDA, Sitarenios G (1999) Self-ratings of ADHD symptoms in adults: II Reliability, validity, and diagnostic sensitivity. J Atten Disord 3(3):153–158. https://doi.org/10.1177/108705479900300304

Conners CK, Erhardt D, Epstein JN, Parker JDA, Sitarenios G, Sparrow E (1999) Self-ratings of ADHD symptoms in adults: I factor structure and normative data. J Atten Disord 3(3):141–151. https://doi.org/10.1177/108705479900300303

Hinshaw SP, Owens EB, Wells KC, Kraemer HC, Abikoff HB, Arnold LE, Conners CK, Elliott G, Greenhill LL, Hechtman L, Hoza B, Jensen PS, March JS, Newcorn JH, Pelham WE, Swanson JM, Vitiello B, Wigal T (2000) Family processes and treatment outcome in the MTA: negative/ineffective parenting practices in relation to multimodal treatment. J Abnorm Child Psychol 28(6):555–568

Muthén BO (2001) Latent variable mixture modeling. In: New developments and techniques in structural equation modeling. Psychology Press, NJ0 07430, pp 21–54

Nylund KL, Asparouhov T, Muthén BO (2007) Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: a Monte Carlo simulation study. Struct Equ Model 14(4):535–569

Beauchaine TP, Gartner J, Hagen B (2000) Comorbid depression and heart rate variability as predictors of aggressive and hyperactive symptom responsiveness during inpatient treatment of conduct-disordered ADHD boys. Aggressive Behav 26(6):425–441. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-2337(200011)26:6%3c425:Aid-Ab2%3e3.0.Co;2-I

MTA (2004) National institute of mental health multimodal treatment study of ADHD follow-up: 24-month outcomes of treatment strategies for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics 113(4):754–761

Weinstein CS, Apfel RJ, Weinstein SR (1998) Description of mothers with ADHD with children with ADHD. Psychiatry 61(1):12–19

Chronis AM, Lahey BB, Pelham WE Jr, Kipp HL, Baumann BL, Lee SS (2003) Psychopathology and substance abuse in parents of young children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 42(12):1424–1432. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200312000-00009

Cloninger CR, Svrakic DM, Przybeck TR (1993) A psychobiological model of temperament and character. Arch Gen Psychiatry 50(12):975–990. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820240059008

Lazarsfeld PF, HN W (1968) Latent structure analysis, vol 3. Houghton Mifflin, New York, p 35

Acknowledgements

The Multimodal Treatment Study of Children with ADHD (MTA) was a National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) cooperative agreement randomized clinical trial involving six clinical sites. Collaborators from NIMH: Peter S. Jensen, M.D. (currently at Reach Institute), L. Eugene Arnold, M.D., M.Ed. (currently at Ohio State University), Joanne B. Severe, M.S. (Clinical Trials Operations and Biostatistics Unit, Division of Services and Intervention Research), Benedetto Vitiello, M.D. (Child and Adolescent Treatment and Preventive Interventions Research Branch), John Richters, Ph.D. (currently at National Institute of Nursing Research), Donald Vereen, M.D. (currently at National Institute on Drug Abuse). Principal investigators and co-investigators from the six sites were: University of California, Berkeley/San Francisco: Stephen P. Hinshaw, Ph.D. (Berkeley), Glen R. Elliott, Ph.D., M.D. (San Francisco); Duke University: C. Keith Conners, Ph.D. (posthumous), Karen C. Wells, Ph.D., John March, M.D., M.P.H.; University of California, Irvine/Los Angeles: James Swanson, Ph.D. (Irvine), Dennis P. Cantwell, M.D., (deceased, Los Angeles), Timothy Wigal, Ph.D. (Irvine); Long Island Jewish Medical Center/Montreal Children’s Hospital: Howard B. Abikoff, Ph.D., Lily Hechtman, M.D. (McGill University); New York State Psychiatric Institute/Columbia University/Mount Sinai Medical Center: Laurence L. Greenhill, M.D. (Columbia), Jeffrey H. Newcorn, M.D. (Mount Sinai School of Medicine); University of Pittsburgh: William E. Pelham, Ph.D. (currently at Florida International University), Betsy Hoza, Ph.D. (currently at University of Vermont). Statistical and design consultant: Helena C. Kraemer, Ph.D. (Stanford University). Collaborator from the Office of Special Education Programs/US Department of Education: Ellen Schiller, Ph.D. This research was supported in part by cooperative agreement grants from NIMH to the following: University of California—Berkeley: U01 MH50461; Duke University: U01 MH50477; University of California—Irvine: U01MH50440; Research Foundation for Mental Hygiene (New York State Psychiatric Institute/Columbia University): U01 MH50467; Long Island—Jewish Medical Center U01 MH50453; University of Pittsburgh: U01 MH50467.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Dr. Arnold has received research funding from Curemark, Forest, Lilly, Neuropharm, Novartis, Noven, Shire, Supernus, Roche, and YoungLiving (as well as NIH and Autism Speaks), has consulted with Gowlings, Neuropharm, Organon, Pfizer, Sigma Tau, Shire, Tris Pharma, and Waypoint, and been on advisory boards for Arbor, Ironshore, Novartis, Noven, Otsuka, Pfizer, Roche, Seaside Therapeutics, Sigma Tau, Shire. Dr. Sibley has consulted with Takeda. Dr. Hechtman has received research support, served on advisory boards, and been a speaker for Ortho-Janssen, Purdue, Shire, and Ironshore, and received book royalties from Guilford, APA, John Hopkins, and Oxford University Press. Drs. Perez Algorta, MacPherson, Hinshaw and Owens report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Perez Algorta, G., MacPherson, H.A., Arnold, L.E. et al. Maternal personality traits moderate treatment response in the Multimodal Treatment Study of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 29, 1513–1524 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-019-01460-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-019-01460-z