Abstract

Background

Routine screening for frailty could be used to timely identify older people with increased vulnerability und corresponding medical needs.

Objective

The aim of this study was the translation and cross-cultural adaptation of the PRISMA-7 questionnaire, the FRAIL scale and the Groningen Frailty Indicator (GFI) into the German language as well as a preliminary analysis of the diagnostic test accuracy of these instruments used to screen for frailty.

Methods

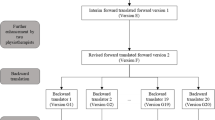

A diagnostic cross-sectional study was performed. The instrument translation into German followed a standardized process. Prefinal versions were clinically tested on older adults who gave structured in-depth feedback on the scales in order to compile a final revision of the German language scale versions. For the analysis of diagnostic test accuracy (criterion validity), PRISMA-7, FRAIL scale and GFI were considered the index tests. Two reference tests were applied to assess frailty, either based on Fried’s model of a Physical Frailty Phenotype or on the model of deficit accumulation, expressed in a Frailty Index.

Results

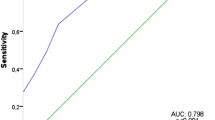

Prefinal versions of the German translations of each instrument were produced and completed by 52 older participants (mean age: 73 ± 6 years). Some minor issues concerning comprehensibility and semantics of the scales were identified and resolved. Using the Physical Frailty Phenotype (frailty prevalence: 4%) criteria as a reference standard, the accuracy of the instruments was excellent (area under the curve AUC >0.90). Taking the Frailty Index (frailty prevalence: 23%) as the reference standard, the accuracy was good (AUC between 0.73 and 0.88).

Conclusion

German language versions of PRISMA-7, FRAIL scale and GFI have been established and preliminary results indicate sufficient diagnostic test accuracy that needs to be further established.

Zusammenfassung

Hintergrund

Die Verwendung von Routine-Screenings auf Frailty könnte helfen, ältere Menschen erhöhter Vulnerabilität und entsprechendem Versorgungsbedarf frühzeitig zu identifizieren.

Ziel

Das Ziel dieser Studie war die Übersetzung und interkulturelle Adaptation des PRISMA-7-Fragebogens, der FRAIL-Skala und des Groningen Frailty Indicators (GFI) in die deutsche Sprache, verbunden mit einer ersten Analyse der diagnostischen Testgenauigkeit dieser Messinstrumente im Screening auf Frailty.

Methoden

Es wurde eine diagnostische Querschnittsstudie durchgeführt. Die Übersetzung der Fragebögen in die deutsche Sprache folgte einem standardisierten Prozess. Präfinale Versionen wurden mit älteren Menschen klinisch erprobt. Die Teilnehmenden gaben ein vertieftes, strukturiertes Feedback zu den Fragebögen. Dieses Feedback wurde zur finalen Überarbeitung der deutschen Fragebogen-Versionen genutzt. Für die Analyse der diagnostischen Testgenauigkeit (Kriteriumsvalidität) galten PRISMA-7, FRAIL-Skala und GFI als Index-Tests. Zur Bestimmung der Frailty wurden zwei Referenz-Tests erhoben, die entweder auf Frieds Modell eines physischen Frailty-Phänotyps oder dem Modell der Defizitakkumulation, ausgedrückt in einem Frailty-Index, basierten.

Ergebnisse

Es wurden präfinale deutsche Versionen der Fragebögen erstellt und von 52 älteren Teilnehmenden beantwortet (mittleres Alter: 73 ± 6 Jahre). Kleinere Probleme hinsichtlich der Verständlichkeit und Semantik der Fragebögen konnten identifiziert und gelöst werden. Wenn der physische Frailty-Phänotyp (Frailty-Prävalenz: 4 %) als Referenzstandard verwendet wurde, war die Testgenauigkeit der Fragebögen exzellent (AUC >0,90). Wurde der Frailty-Index (Frailty Prävalenz: 23 %) als Referenzstandard verwendet, war die Testgenauigkeit gut (AUC zwischen 0,73 und 0,88).

Schlussfolgerungen

Deutschsprachige Versionen von PRISMA-7, der FRAIL-Skala und dem GFI wurden erstellt. Die ersten Ergebnisse weisen auf eine ausreichende diagnostische Testgenauigkeit hin, die weiter untersucht werden sollte.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Rodriguez-Manas L, Feart C, Mann G et al (2013) Searching for an operational definition of frailty: a Delphi method based consensus statement: the frailty operative definition-consensus conference project. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 68(1):62–67

Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S et al (2013) Frailty in elderly people. Lancet 381(9868):752–762

Kenig J, Zychiewicz B, Olszewska U et al (2015) Six screening instruments for frailty in older patients qualified for emergency abdominal surgery. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 61(3):437–442

Xue Q‑L, Varadhan R (2014) What is missing in the validation of frailty instruments? J Am Med Dir Assoc 15(2):141–142

Morley JE (2014) Frailty screening comes of age. J Nutr Health Aging 18(5):453–454

Clegg A, Rogers L, Young J (2015) Diagnostic test accuracy of simple instruments for identifying frailty in community-dwelling older people: a systematic review. Age Ageing 44(1):148–152

de Vries NM, Staal JB, van Ravensberg CD et al (2011) Outcome instruments to measure frailty: a systematic review. Ageing Res Rev 10(1):104–114

Searle SD, Mitnitski A, Gahbauer EA et al (2008) A standard procedure for creating a frailty index. BMC Geriatr 8:24

Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J et al (2001) Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 56(3):146–156

Hoogendijk EO, van der Horst HE, Deeg DJH et al (2013) The identification of frail older adults in primary care: comparing the accuracy of five simple instruments. Age Ageing 42(2):262–265

Metzelthin SF, Daniels R, van Rossum E et al (2010) The psychometric properties of three self-report screening instruments for identifying frail older people in the community. BMC Public Health 10:176

Pialoux T, Goyard J, Lesourd B (2012) Screening tools for frailty in primary health care: a systematic review. Geriatr Gerontol Int 12(2):189–197

Braun T, Thiel C, Grüneberg C (2016) Diagnostic and screening tools for frailty in older people – overview of systematic reviews. Physioscience 12(4):142–151

Dent E, Kowal P, Hoogendijk EO (2016) Frailty measurement in research and clinical practice: a review. Eur J Intern Med 31:3–10

Morley JE, Vellas B, van Abellan Kan G et al (2013) Frailty consensus: a call to action. J Am Med Dir Assoc 14(6):392–397

Hebert R, Durand PJ, Dubuc N et al (2003) Frail elderly patients. New model for integrated service delivery. Can Fam Physician 49:992–997

Morley JE, Malmstrom TK, Miller DK (2012) A simple frailty questionnaire (FRAIL) predicts outcomes in middle aged African Americans. J Nutr Health Aging 16(7):601–608

Gardiner PA, Mishra GD, Dobson AJ (2015) Validity and responsiveness of the FRAIL scale in a longitudinal cohort study of older Australian women. J Am Med Dir Assoc 16:781–783

Jung H‑W, Yoo H‑J, Park S‑Y et al (2016) The Korean version of the FRAIL scale: clinical feasibility and validity of assessing the frailty status of Korean elderly. Korean J Intern Med 31(3):594–600

Steverink N, Slaets J, Schuurmans H et al (2001) Measuring frailty: developing and testing the GFI (Groningen frailty indicator). Gerontologist 41:236–237

Bielderman A, van der Schans CP, Lieshout M‑RJ et al (2013) Multidimensional structure of the Groningen frailty indicator in community-dwelling older people. BMC Geriatr 13(1):86

Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F et al (2000) Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine 25(24):3186–3191

Bossuyt PM, Reitsma JB, Bruns DE et al (2015) STARD 2015: an updated list of essential items for reporting diagnostic accuracy studies. BMJ 351:h5527

Schuurmans H, Steverink N, Lindenberg S et al (2004) Old or frail: what tells us more? J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 59(9):962–965

Pohontsch N, Meyer T (2015) Cognitive interviewing – a tool to develop and validate questionnaires. Rehabilitation 54(1):53–59

Roberts H, Denison H, Martin H et al (2011) A review of the measurement of grip strength in clinical and epidemiological studies: towards a standardised approach. Age Ageing 40(4):423–429

Taylor HL, Jacobs DR, Schucker B et al (1978) A questionnaire for the assessment of leisure time physical activities. J Chronic Dis 31(12):741–755

Braun T, Thiel C, Schulz R‑J et al (2017) Diagnosis and treatment of physical frailty. Dtsch Med Wochenschr 142(2):117–122

Rockwood K, Andrew M, Mitnitski A (2007) A comparison of two approaches to measuring frailty in elderly people. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 62(7):738–743

Borson S, Scanlan J, Brush M et al (2000) The mini-cog: a cognitive “vital signs” measure for dementia screening in multi-lingual elderly. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 15(11):1021–1027

Murphy JM, Berwick DM, Weinstein MC et al (1987) Performance of screening and diagnostic tests. Application of receiver operating characteristic analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry 44(6):550–555

Collard RM, Boter H, Schoevers RA et al (2012) Prevalence of frailty in community-dwelling older persons: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc 60(8):1487–1492

Shamliyan T, Talley KMC, Ramakrishnan R et al (2013) Association of frailty with survival: a systematic literature review. Ageing Res Rev 12(2):719–736

Epstein J, Santo RM, Guillemin F (2015) A review of guidelines for cross-cultural adaptation of questionnaires could not bring out a consensus. J Clin Epidemiol 68(4):435–441

Epstein J, Osborne RH, Elsworth GR et al (2015) Cross-cultural adaptation of the Health Education Impact Questionnaire: experimental study showed expert committee, not back-translation, added value. J Clin Epidemiol 68(4):360–369

Hobart JC, Cano SJ, Warner TT et al (2012) What sample sizes for reliability and validity studies in neurology? J Neurol 259(12):2681–2694

Theou O, Cann L, Blodgett J et al (2015) Modifications to the frailty phenotype criteria: Systematic review of the current literature and investigation of 262 frailty phenotypes in the Survey of Health, Ageing, and Retirement in Europe. Ageing Res Rev 21:78–94

Freitag S, Schmidt S, Gobbens RJJ (2016) Tilburg frailty indicator. German translation and psychometric testing. Z Gerontol Geriatr 49(2):86–93

Romero-Ortuno R, Walsh CD, Lawlor BA et al (2010) A Frailty Instrument for primary care: findings from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE). BMC Geriatr 10(1):57

Abellan van Kan G, Rolland Y, Bergman H et al (2008) The I.A.N.A Task Force on frailty assessment of older people in clinical practice. J Nutr Health Aging 12(1):29–37

Turner G, Clegg A (2014) Best practice guidelines for the management of frailty: a British Geriatrics Society, Age UK and Royal College of General Practitioners report. Age Ageing 43(6):744–747

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all participants for participating in this study. We further acknowledge the support in data acquisition by Isabelle Stickdorn, Katharina van Baal, Caren Horstmannshoff and the staff of the physiotherapy clinic “Hand drauf” in Bochum. We further thank the colleagues of the expert committees, namely Lena Wulff, Anika Schmitt, Esther Hoolt, Johann Wulff, Ina Bergmann, Rachel Seidenglanz, Christopher Hamley and Jana Zimmermann. Finally, we acknowledge the helpful, patient and constructive support by Nardi Steverink, Michel Raîche and John Morley.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interests

T. Braun, C. Grüneberg and C. Thiel declare that they have no competing interests.

All studies described in this manuscript were carried out in accordance with national law and the Helsinki Declaration from 1964 (in its current revised form). This study was approved by the Ethical Review Board of the German Confederation for Physiotherapy (registration number 2014-02). All participants provided written informed consent.

Additional information

Author contributions Study concept and design: TB, CG, CT. Acquisition of data: TB. Analysis of data: TB. Interpretation of data: TB, CG, CT. Drafting the manuscript: TB. Manuscript revision for important intellectual content: CG, CT. Final approval of the version to be published: TB, CG, CT.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Braun, T., Grüneberg, C. & Thiel, C. German translation, cross-cultural adaptation and diagnostic test accuracy of three frailty screening tools. Z Gerontol Geriat 51, 282–292 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00391-017-1295-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00391-017-1295-2