Abstract

Background

Rectal bleeding is considered an alarm symptom for colorectal cancer (CRC) but it is common and mostly caused by benign conditions. Qualitative faecal immunochemical tests (FITs) for occult blood have been used as diagnostic aids for many years in Sweden when CRC is suspected. The study aimed to evaluate the usefulness of FITs requested by primary care physicians for patients with and without histories of rectal bleeding, in the diagnosis of CRC.

Methods

Results of all FITs requested in primary care for symptomatic patients in the Örebro region during 2015 were retrieved. Data on each patient’s history of rectal bleeding was gathered from electronic health records. Patients diagnosed with CRC within 2 years were identified from the Swedish Cancer Register. The analysis focused on three-sample FITs, the customary FIT in Sweden.

Results

A total of 4232 patients provided three-sample FITs. Information about the presence/absence of rectal bleeding was available for 2027 patients, of which 59 were diagnosed with CRC. For 606 patients with the presence of rectal bleeding, the FIT showed sensitivity 96.2%, specificity 60.2%, positive predictive value 9.8% (95% CI 6.1–13.4) and negative predictive value 99.7% (95% CI 99.2–100) for CRC. For 1421 patients without rectal bleeding, the corresponding figures were 100%, 73.6%, 8.3% (95% CI 5.6–10.9) and 100% (95% CI 99.6–100).

Conclusion

The diagnostic performance of a qualitative three-sample FIT provided by symptomatic patients in primary care was similar for those with and without a history of rectal bleeding. FITs seem useful for prioritising patients also with rectal bleeding for further investigation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer worldwide with over 1.8 million new cases registered in 2018 [1]. The majority of symptomatic patients diagnosed with CRC initially consult primary care [2].

Rectal bleeding is associated with CRC and is considered an alarm symptom [3]. It is also a common symptom in the general population and it is mostly caused by benign conditions such as haemorrhoids or anal fissures [4,5,6]. In primary care, it can be difficult to determine if a patient’s history of rectal bleeding can be explained by the patient’s haemorrhoids or if it could emanate from CRC and thus, the patient should be referred to secondary care.

Guidelines on CRC recommend that patients with unexplained rectal bleeding should be referred for further examinations, usually sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy [7,8,9,10]. These procedures are resource heavy, unpleasant for the patients and constitute a small risk for morbidity and even mortality [11]. A test to facilitate the selection of patients for colonoscopy with greater certainty than relying on a history of rectal bleeding only would therefore be useful.

Tests for faecal occult blood have been in use for many years for CRC screening in several countries [12]. Guaiac-based tests (haemoccult) are now being replaced by immunochemical faecal occult blood tests (FITs) which are more sensitive and react only to human blood [13,14,15,16]. In the UK, FITs are also recommended for use for symptomatic patients without rectal bleeding that do not meet the criteria stated in the “Suspected cancer: recognition and referral” pathway for CRC [17].

In Sweden, faecal occult blood tests have been used as diagnostic aids in clinical practice in primary care as well as in secondary care for many years. There is no national screening programme and faecal occult blood tests are not included in the suspected cancer pathway recommendations. In around 2005, guaiac-based tests were abandoned in favour of qualitative FITs. These FITs can easily be analysed at primary care centres (PCCs); they use a chromatographic technique with pre-set cutoffs and are visually read by identifying coloured lines.

Evidence is growing that FITs are useful as diagnostic tests in primary care before decisions are taken on the referral of symptomatic patients [18,19,20,21]. Studies on patients already referred to secondary care have included those with a history of rectal bleeding [22,23,24,25,26,27]. To our knowledge, no study in primary care has compared FIT results for patients presenting with and without rectal bleeding, respectively.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the usefulness of qualitative FITs requested by primary care physicians (PCPs) for symptomatic patients with and without histories of rectal bleeding, in the diagnosis of CRC.

Method

We registered the results of all FITs for patients aged ≥ 18 years requested by PCPs from 1 January to 31 December 2015 at all PCCs in the region of Örebro in Sweden (population 290,890 on 1 November 2015). These data were retrieved from the region’s electronic health record system, NCS Cross, used by all PCCs [28]. Samples registered within 14 days of each other were considered as belonging to the same FIT. The date of the FIT was set as the date of the first faecal sample. If more than one FIT had been provided during the year, we registered the first FIT only. The FIT was considered as positive if one or more of the samples tested positive. When a FIT is requested in Sweden, at most PCCs, it is customary to analyse three faecal samples collected from consecutive bowel movements on different days for each FIT (a three-sample FIT). The analyses in this study were focused on cases with three-sample FITs.

The qualitative FIT Actim Fecal Blood was used for the analyses [29]. Instructions on sampling, storage and analysis were issued by the Department of Laboratory Medicine at the Örebro University Hospital and followed by all PCCs in the region. Actim Fecal Blood is an immunochromatographic dipstick test, in which patients collected an expected mass of 10–20 mg of faeces with a sampling stick attached to a cap which was inserted into a tube with 10 ml of buffer solution. The FITs were analysed by laboratory staff at each PCC laboratory, which were all accredited by Swedac (Sweden’s national accreditation body) and supervised by the Department of Laboratory Medicine at the Örebro University Hospital [30]. Tests were visually interpreted by identifying a coloured line for a positive test. Each dipstick had a built-in control line for quality assurance. The cutoff for a positive result was 50 ng haemoglobin/ml of faecal solution corresponding to 25–50 μg haemoglobin/g faeces, and the test remained positive at 500 ng haemoglobin/ml faecal solution, according to the manufacturer’s instruction at the time of the study. Collected samples could be stored for up to 7 days at room temperature before analysis.

For patients that provided FITs, data on the history of rectal bleeding from 1 month before until 1 month after the FIT date was gathered from the electronic health record system through free text search. The electronic search application Medrave was used for this purpose [31]. All paragraphs with words containing “blood” or “bleed” (“blod” or “blöd” in Swedish) were extracted and these were read by one of the authors (CH). Only phrases that explicitly confirmed or denied a history of blood seen in the faeces, in the toilet or on the toilet paper, were registered. For example, phrases about dark or black faeces, phrases stating that there were no defecation problems or that the faeces looked normal, or where patients were uncertain about the presence of blood, were omitted. For quality control of the electronic search result, the health records for all patients diagnosed with colorectal cancer were also read in full and data from these were extracted by one of the authors (SJ). The results from these readings were compared with the electronic search results for the same patients by CH.

Patients diagnosed with CRC within 2 years after their FIT date were identified from the Swedish Cancer Register [32]. The limit of 2 years was chosen as this is the recommended interval for CRC screening in Europe and it has been used in prior primary care studies concerning FITs in symptomatic patients [18, 20, 33, 34]. Also, it seems likely that a patient having CRC but a negative FIT should be diagnosed within 2 years.

Statistics

SPSS version 24 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) was used for statistical analysis. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) with 95% confidence intervals (CI), as well as the positive and negative likelihood ratios (LR) of FITs for the diagnosis of CRC were calculated for patients with and without a history of rectal bleeding.

Results

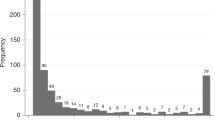

In total, 5683 (59.9% women) patients at 29 PCCs provided FITs with one to eight samples (Fig. 1). The median age was 64 years (interquartile range [IQR] = 45–76 years). Three-sample FITs were provided by 4232 patients (74.5%; 60.7% women, median age 62 years [IQR = 43–74]). Of all 5683 patients, 107 (1.9%; 43.0% women, median age 75 years [IQR = 66–82]) were diagnosed with CRC within 2 years. Of the 4232 patients that provided three-sample FITs, 79 (1.9%; 45.6% women, median age 73 years [IQR = 64–81]) were diagnosed with CRC (Table 1).

Information about the presence or absence of rectal bleeding was available for 2404 patients, of which 2027 (84.3%; 62.0% women, median age 58 years [IQR = 39–71]) provided three-sample FITs. Of these 2027 patients, 59 (2.9%; 45.8% women, median age 71 years [IQR = 64–80]) were subsequently diagnosed with CRC; 26 with and 33 without rectal bleeding (Table 2). In total, rectal bleeding was registered for 606 (29.9%) of the 2027 patients with three-sample FITs. For patients with a history of rectal bleeding, the sensitivity for CRC of a three-sample FIT was 96.2%, the specificity was 60.2%, the PPV was 9.8% (95% CI 6.1–13.4) and the NPV 99.7% (95% CI 99.2–100). Corresponding values for patients without rectal bleeding were 100%, 73.6%, 8.3% (95% CI 5.6–10.9) and 100% (95% CI 99.6–100) respectively. One patient with a history of rectal bleeding and a negative FIT was diagnosed with CRC. This cancer was registered as ICD-10 C18.1 (malignant neoplasm of the appendix).

History of rectal bleeding, irrespective of FIT results, showed a sensitivity of 44.1%, a specificity of 70.5% and a PPV of 4.3% (95% CI 2.7–5.9) for CRC when calculated for the 2027 patients who provided three-sample FITs.

For all patients providing three-sample FITs and diagnosed with CRC, the median time to diagnosis was 76 days (IQR = 48–188). For the 26 patients with rectal bleeding, the median time to diagnosis was 64 days (IQR = 38–169) while for the 33 patients without rectal bleeding, the median time was 89 days (IQR = 58–291).

Contents in the electronic health record entries retrieved with Medrave corresponded to the contents found in the manually scrutinized electronic health records for all the 107 patients diagnosed with CRC. No additional information about rectal bleeding was found when reading the entire texts and no electronically retrieved information was found to be incorrect.

Discussion

Results of all FITs requested in primary care for symptomatic patients in a Swedish region during 2015 were retrieved, and CRC cases diagnosed within 2 years were identified from the Swedish Cancer Register. The diagnostic performance in the detection of CRC using a qualitative three-sample FIT was similar in patients with a history of rectal bleeding compared with those with no rectal bleeding and was better than that of a history of rectal bleeding alone. This indicates that FITs may be useful for prioritising patients for further investigation also when they have experienced rectal bleeding.

Previous studies with patients referred to secondary care have shown FITs to be superior to English national guidelines (NG12), which include referral of patients aged 50 and over with unexplained rectal bleeding and patients aged 40 and over with unexplained rectal bleeding combined with other symptoms [22, 35]. In the present primary care study, FITs showed a higher sensitivity as well as a higher PPV for CRC than a history of rectal bleeding. This supports the use of FITs, which seem potentially preferable to decision-making based on rectal bleeding only.

This study has some limitations. It is retrospective and information about the presence or absence of rectal bleeding was available for less than half of the patients. It seems probable that PCPs have different habits concerning phrases used in medical records, that patients with information about rectal bleeding may not be equally distributed between PCPs and that the presence or absence of rectal bleeding may be registered more often in patients with more serious symptoms. It is also possible that the presence of rectal bleeding was recorded to a greater extent than the absence of bleeding. On the other hand, in four studies on patients referred to secondary care with the same magnitude of CRC diagnoses as in this study (3.0–5.4%), and where a history of rectal bleeding was registered, the prevalence of rectal bleeding was 24.8–36.0% which is similar to the 29.9% in this study [23, 24, 26, 27]. Another aspect is that only patients for whom FITs were requested and subsequently provided were included in the study, and it is probable that an unknown number of patients with rectal bleeding were referred without providing FITs. However, the study reflects the clinical situation and it seems likely that the PCPs requested FITs when they were in need of a diagnostic aid.

The study also has a number of strengths. It is population-based and data on FITs were collected from electronic health records with complete coverage of the region’s PCCs, including cities as well as rural areas. The electronically retrieved data about rectal bleeding seem reliable, as a comparison of Medrave search results with the manually scrutinized electronic health records for patients diagnosed with CRC revealed no discrepancies. It is unlikely that patients with the occurrence of a CRC diagnosis were missed, as the Swedish Cancer Register has almost total coverage and completeness [36]. Furthermore, the organisation of the public Swedish health care system and the accreditation of the PCC laboratories by Swedac guarantees uniform processing of samples in all PCCs included.

To our knowledge, this is the first study in primary care that evaluates FIT results for patients with a history of rectal bleeding. In a recently published Swedish study, 60 patients referred for colonoscopy had a history of rectal bleeding, and a FIT with a cutoff of > 10 μg Hb/g faeces showed 100% sensitivity, 74.1% specificity, 30.0% PPV and 100% NPV for CRC for these patients [27]. A Scottish study evaluating the accuracy of a quantitative FIT and faecal calprotectin in patients referred for investigation of bowel symptoms, and in which 33.9% of the patients had a documented history of rectal bleeding, showed a 4.3% PPV of rectal bleeding for CRC which is similar to the present study [24]. An English study examining the diagnostic accuracy of a quantitative FIT provided by patients referred to secondary care, in which 36% of the patients had a documented history of rectal bleeding, found that there was only a small difference in the optimal one-sample FIT cutoff value for patients with rectal bleeding versus no bleeding [26].

To conclude, qualitative FITs seem useful for prioritising patients with rectal bleeding in primary care for further investigation. Future prospective studies are desired to further evaluate the accuracy of FITs in patients with rectal bleeding, including the optimal number of samples per FIT and the optimal cutoff value.

Availability of data and material

Data is available from the authors upon reasonable request.

References

International Agency for Research on Cancer. Global Cancer Observatory. Cancer today. https://gco.iarc.fr/today/home Accessed 4 May 2020

Weller D, Menon U, Zalounina Falborg A, Jensen H, Barisic A, Knudsen AK, Bergin RJ, Brewster DH, Cairnduff V, Gavin AT, Grunfeld E, Harland E, Lambe M, Law RJ, Lin Y, Malmberg M, Turner D, Neal RD, White V, Harrison S, Reguilon I, ICBP Module 4 Working Group, Vedsted P (2018) Diagnostic routes and time intervals for patients with colorectal cancer in 10 international jurisdictions; findings from a cross-sectional study from the International Cancer Benchmarking Partnership (ICBP). BMJ Open 8:e023870. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023870

Astin M, Griffin T, Neal RD, Rose P, Hamilton W (2011) The diagnostic value of symptoms for colorectal cancer in primary care: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract 61:e231–e243. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp11X572427

Elnegaard S, Andersen RS, Pedersen AF, Larsen PV, Sondergaard J, Rasmussen S et al (2015) Self-reported symptoms and healthcare seeking in the general population - exploring “The Symptom Iceberg”. BMC Public Health 15:685. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-2034-5

Hannaford PC, Thornton AJ, Murchie P, Whitaker KL, Adam R, Elliott AM (2020) Patterns of symptoms possibly indicative of cancer and associated help-seeking behaviour in a large sample of United Kingdom residents-the USEFUL study. PLoS One 15:e0228033. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0228033

Jones R, Charlton J, Latinovic R, Gulliford MC (2009) Alarm symptoms and identification of non-cancer diagnoses in primary care: cohort study. BMJ 339:b3094. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b3094

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2015) Suspected cancer: recognition and referral. NG 12. http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng12. Accessed 4 May 2020

Regionala cancercentrum i samverkan (2015) Standardiserade vårdförlopp (SVF). https://www.cancercentrum.se/samverkan/vara-uppdrag/kunskapsstyrning/vardforlopp/. Accessed 4 May 2020

Sundhetsstyrelsen (2012) Pakkeforløb for kræft i tyk- og endetarm. https://www.sst.dk/da/sygdom-og-behandling/kraeft/pakkeforloeb/. Accessed 4 May 2020

Helsedirektoratet. Pakkeforløp for tykk- og endetarmskreft. https://helsedirektoratet.no/retningslinjer/pakkeforlop-for-tykk-og-endetarmskreft/seksjon? Tittel=inngang-til-pakkeforlop-for-1368#risikogrupper. Accessed 4 May 2020

Hoff G, de Lange T, Bretthauer M, Buset M, Dahler S, Halvorsen FA, Halwe J, Heibert M, Høie O, Kjellevold Ø, Moritz V, Sandvei P, Seip B, Aabakken L, Holme Ø (2017) Patient-reported adverse events after colonoscopy in Norway. Endoscopy 49:745–753. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0043-105265

Benard F, Barkun AN, Martel M, von Renteln D (2018) Systematic review of colorectal cancer screening guidelines for average-risk adults: summarizing the current global recommendations. World J Gastroenterol 24:124–138. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v24.i1.124

European Colorectal Cancer Screening Guidelines Working Group, von Karsa L, Patnick J, Segnan N, Atkin W, Halloran S, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I et al (2013) European guidelines for quality assurance in colorectal cancer screening and diagnosis: overview and introduction to the full supplement publication. Endoscopy 45:51–59. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0032-1325997

Sung JJY, Ng SC, Chan FKL, Chiu HM, Kim HS, Matsuda T, Ng SS, Lau JY, Zheng S, Adler S, Reddy N, Yeoh KG, Tsoi KK, Ching JY, Kuipers EJ, Rabeneck L, Young GP, Steele RJ, Lieberman D, Goh KL, Asia Pacific Working Group (2015) An updated Asia Pacific Consensus Recommendations on colorectal cancer screening. Gut 64:121–132. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2013-306503

Rex DK, Boland RC, Dominitz JA, Giardiello FM, Johnson DA, Kaltenbach T et al (2017) Colorectal cancer screening: recommendations for physicians and patients from the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology 153:307–323. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2017.05.013

Aronsson M, Carlsson P, Levin LÅ, Hager J, Hultcrantz R (2017) Cost-effectiveness of high-sensitivity faecal immunochemical test and colonoscopy screening for colorectal cancer. Br J Surg 104:1078–1086. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.10536

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2017) Quantitative faecal immunochemical tests to guide referral for colorectal cancer in primary care. DG30 https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/dg30/. Accessed 4 May 2020

Högberg C, Karling P, Rutegård J, Lilja M (2017) Diagnosing colorectal cancer and inflammatory bowel disease in primary care: the usefulness of tests for faecal haemoglobin, faecal calprotectin, anaemia and iron deficiency. A prospective study. Scand J Gastroenterol 52:69–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/00365521.2016.1228120

Juul JS, Hornung N, Andersen B, Laurberg S, Olesen F, Vedsted P (2018) The value of using the faecal immunochemical test in general practice on patients presenting with non-alarm symptoms of colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer 119:471–479. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-018-0178-7

Mowat C, Digby J, Strachan JA, McCann R, Hall C, Heather D, Carey F, Fraser CG, Steele RJC (2019) Impact of introducing a faecal immunochemical test (FIT) for haemoglobin into primary care on the outcome of patients with new bowel symptoms: a prospective cohort study. BMJ Open Gastroenterol 6:e000293. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgast-2019-000293

Chapman C, Thomas C, Morling J, Tangri A, Oliver S, Simpson JA, Humes DJ, Banerjea A (2019) Early clinical outcomes of a rapid colorectal cancer diagnosis pathway using faecal immunochemical testing in Nottingham. Color Dis. https://doi.org/10.1111/codi.14944

Cubiella J, Salve M, Diaz-Ondina M, Vega P, Alves MT, Iglesias F et al (2014) Diagnostic accuracy of the faecal immunochemical test for colorectal cancer in symptomatic patients: comparison with NICE and SIGN referral criteria. Color Dis 16:O273–O282. https://doi.org/10.1111/codi.12569

Rodriguez-Alonso L, Rodriguez-Moranta F, Ruiz-Cerulla A, Lobaton T, Arajol C, Binefa G et al (2015) An urgent referral strategy for symptomatic patients with suspected colorectal cancer based on a quantitative immunochemical faecal occult blood test. Dig Liver Dis 47:797–804. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dld.2015.05.004

Mowat C, Digby J, Strachan JA, Wilson R, Carey FA, Fraser CG, Steele RJ (2016) Faecal haemoglobin and faecal calprotectin as indicators of bowel disease in patients presenting to primary care with bowel symptoms. Gut 65:1463–1469. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309579

Widlak MM, Thomas CL, Thomas MG, Tomkins C, Smith S, O’Connell N, Wurie S, Burns L, Harmston C, Evans C, Nwokolo CU, Singh B, Arasaradnam RP (2017) Diagnostic accuracy of faecal biomarkers in detecting colorectal cancer and adenoma in symptomatic patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 45:354–363. https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.13865

Turvill J, Mellen S, Jeffery L, Bevan S, Keding A, Turnock D (2018) Diagnostic accuracy of one or two faecal haemoglobin and calprotectin measurements in patients with suspected colorectal cancer. Scand J Gastroenterol 53:1526–1534. https://doi.org/10.1080/00365521.2018.1539761

Tsapournas G, Hellström PM, Cao Y, Olsson LI (2020) Diagnostic accuracy of a quantitative faecal immunochemical test vs. symptoms suspected for colorectal cancer in patients referred for colonoscopy. Scand J Gastroenterol 55:184–192. https://doi.org/10.1080/00365521.2019.1708965

Tieto EVRY ASA. https://www.evry.com/en/. Accessed 4 May 2020

Oy Medix Biochemica Ab. https://www.medixbiochemica.com. Accessed 4 May 2020

Sweden’s national accreditation body, Swedac. https://www.swedac.se/?lang=en. Accessed 4 May 2020

Medrave Software AB. www.medrave.com. Accessed 4 May 2020

Cancerregistret. https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/en/statistics-and-data/registers/register-information/swedish-cancer-register/. Accessed 4 May 2020

Segnan N, Patnik J, von Karsa L (editors) (2010) European Guidelines for Quality Assurance in Colorectal Cancer Screening and Diagnosis - first edition. European Union. https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/e1ef52d8-8786-4ac4-9f91-4da2261ee535. Accessed 4 May 2020

Högberg C, Karling P, Rutegard J, Lilja M, Ljung T (2013) Immunochemical faecal occult blood tests in primary care and the risk of delay in the diagnosis of colorectal cancer. Scand J Prim Health Care 31:209–214. https://doi.org/10.3109/02813432.2013.850205

Herrero J-M, Vega P, Salve M, Bujanda L, Cubiella J (2018) Symptom or faecal immunochemical test based referral criteria for colorectal cancer detection in symptomatic patients: a diagnostic tests study. BMC Gastroenterol 18:155. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-018-0887-7

Barlow L, Westergren K, Holmberg L, Talback M (2009) The completeness of the Swedish Cancer Register: a sample survey for year 1998. Acta Oncol 48:27–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/02841860802247664

Funding

Open access funding provided by Umea University. This study was supported by unrestricted grants from Region Jämtland Härjedalen, Region Kronoberg, the Cancer Research Foundation in Northern Sweden and Jämtland’s Cancer and Nursing foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Cecilia Högberg and Mikael Lilja designed the study. Data collection was performed by Cecilia Högberg and Stefan Jansson. Cecilia Högberg performed the analysis. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Cecilia Högberg and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board, Umeå University (Ethics approval 2017/451-31).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Högberg, C., Gunnarsson, U., Cronberg, O. et al. Qualitative faecal immunochemical tests (FITs) for diagnosing colorectal cancer in patients with histories of rectal bleeding in primary care: a cohort study. Int J Colorectal Dis 35, 2035–2040 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-020-03672-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-020-03672-1