Abstract

Purpose

The recurrence rate of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) after fundoplication has been reported to be 7–25%. We investigated the risk factors for recurrence of GERD after Thal fundoplication (TF) in our department with the aim of further reducing the recurrence rate of GERD.

Methods

We retrospectively analyzed 276 patients who underwent TF for GERD at our hospital between 2000 and 2019. Retrospectively considered variables were obtained from the medical records of patients. The variables included patient characteristics, GERD severity, surgery-related factors and postoperative course.

Results

The postoperative GERD recurrence rate was 5.8%. In the univariate analysis, the presence of convulsive seizures (12/4 vs. 110/150, p = 0.046) and the absence of a tracheostomy (0/16 vs. 53/207, p = 0.048) at the time of TF were significantly associated with recurrence. In the multivariate analysis, the presence of convulsive seizures at the time of TF was the only factor significantly associated with recurrence.

Conclusion

The presence of convulsive seizures and the absence of a tracheostomy at the time of TF were significantly associated with GERD recurrence after TF. Active control of seizures and consideration of surgical indications, including assessment of respiratory status, are important in preventing the recurrence of GERD after TF.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) has a wide spectrum of symptoms, including esophagitis (resulting from refluxed gastric acid disturbing the esophageal mucosa); aspiration pneumonia (due to the influx of reflux into the trachea); and asthma attacks due to apnea (via the vagus reflex). An association between GERD and apparent life-threatening events such as these has been reported [1]. This association is especially common among patients with severe motor and intellectual disabilities [2]. Surgical treatment should be considered for patients with persistent GERD who resist alternative medical treatment, or for those who have difficulty withdrawing from medical treatment. The most common fundoplication procedure is Nissen fundoplication (NF) [3, 4]. In the 1970s and the 1980s, NF was performed for GERD. However, since we experienced lengthy operative times for laparoscopic surgery and had many postoperative complications (such as gas-bloat syndrome) with NF, we considered alternative surgical procedures. The TF technique was therefore introduced to our surgical department in 1998 because we considered its more physiological approach to be briefer and less complicated than the NF approach. We reported [5] that the Thal fundoplication (TF) technique may be an effective and simple treatment for GERD, with few recurrences and without the complications common to NF. The advantages of TF include: (1) no surgical interference with the short gastric artery and vein, (2) brief surgery and operative time, (3) few wrap migrations, and (4) low prevalence of gas-bloat syndrome.

In most cases of GERD, fundoplication is performed to improve the patient’s quality of life (QOL), not to cure the disease. Because of this, GERD recurrence is one of the complications that surgeons most dislike. The recurrence rate of GERD after fundoplication has been reported to be 3.2–45% [6,7,8]. Few studies have examined the risk factors for the recurrence of GERD after TF. In the present study, we investigated the risk factors for the recurrence of GERD after TF, with the aim of further reducing the recurrence rate of GERD.

Materials and methods

Subject selection

The subjects included 276 patients who had undergone TF for GERD at our hospital between 2000 and 2019. The follow-up period was set at 2 years (minimum). Our department has five indicators for the surgical intervention of GERD:

-

(1)

vomiting, pneumonia, apnea, and discomfort

-

(2)

exclusion of other disorders by upper gastrointestinal imaging

-

(3)

esophageal pH-monitored regurgitation rate of 4% or more

-

(4)

a modest attempt at other, less invasive treatments

-

(5)

granting informed consent to participate in the study.

Quantified variables

Retrospectively considered variables were obtained from the medical records of patients. The variables included age, body weight, underlying disease, convulsive seizure (for those who experienced convulsive seizures during hospital stay), preoperative tracheostomy, preoperative esophageal pH-monitored reflux rate, preoperative reflux grade (Grade 1: reflux into distal esophagus only, 2: reflux extending above carina but not into cervical esophagus, 3: reflux into cervical esophagus, 4: free persistent reflux in the cervical esophagus with a widely patent cardia, 5: reflux with aspiration into the trachea or lung) [9], operative method (laparotomy, laparoscopic or laparotomy conversion), operative time (exclusive of any time taken to perform simultaneous surgeries, such as gastrostomy), volume of bleeding, time to commencing postoperative enteral feeding, time to achieving postoperative full enteral feeding, length of hospital stay, complications (Clavien–Dindo classification) [10], and recurrence.

Postoperative GERD recurrence was defined as ‘a recurrence of symptoms (vomiting, pneumonia, apnea, and discomfort) associated with GERD, and reflux on upper gastrointestinal imaging.’

Thal fundoplication procedure

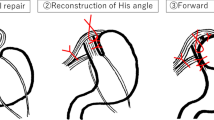

The abdominal esophagus (at least 3 cm in length) was taped. After exposing the left and right crura of the diaphragm, the esophageal hiatus was ligated on the dorsal side of the esophagus (crural repair). Next, the fundus of the stomach was sutured to both the left wall of the abdominal esophagus and to the left crus of the diaphragm as an anchoring suture to prevent wrap migration. The stomach and left wall of the esophagus were sutured to reconstruct the His angle. Furthermore, the greater curvature of the stomach dome was sutured to both the right wall of the abdominal esophagus and the right crus of the diaphragm as an anchoring suture to prevent wrap migration. The stomach and right wall of the esophagus were sutured and wrapped over 180° anteriorly [11].

Our inclusion criteria for laparoscopic surgery are listed as follows:

-

(1) body weight of 5 kg or more

-

(2) no history of major abdominal surgery (patients with minor operations, such as gastrostomy, were excluded)

-

(3) no severe cardiorespiratory complications

-

(4) no joint contractures or severe scoliosis

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using EZR (Easy R, Ver. 1.41) [12]. This software, which is based on R and R commander, is freely available on the website (http://www.jichi.ac.jp/saitama-sct/SaitamaHP.files/statmed.html) and runs on Windows (Microsoft Corporation, USA). Fisher’s exact test and t-test were used for the univariate analysis. Logistic regression analysis was used for the multivariate analysis. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

The results are shown in Table 1.

The postoperative GERD recurrence rate was 5.8% (16 cases out of 276 cases).

There were no significant differences in gender (4/12 vs. 97/163, p = 0.427), age (15.82 ± 17.56 vs. 16.51 ± 18.55, p = 0.887) and body weight (22.94 ± 14.62 vs. 20.55 ± 16.11, p = 0.562) when compared by recurrence status. To assess the severity of GERD, preoperative esophageal pH-monitored reflux rate (14.12 ± 7.75, 13.83 ± 11.05, p = 0.919) and preoperative reflux grade (2.250.58 1.97 ± 0.76, p = 0.156) were compared between patients with and without recurrence, but no significant difference was found.

The presence of convulsive seizures (14/2 vs. 28/232, p = 0.026) and the absence of a tracheostomy (0/16 vs. 53/207, p = 0.048) at the time of TF were significantly associated with recurrence.

For representative underlying diseases (hiatal hernia, esophageal atresia, diaphragmatic hernia, chromosomal abnormality, and heart disease), we tested for a relationship with recurrence, but found none.

No significant relationship to recurrence was found for factors related to surgery (operative procedure, operative time, and volume of bleeding). The postoperative course (time of restart feed, time of full feed, and length of hospital stay) and complications were not significantly related to recurrence either.

In multivariate analysis, the presence of convulsive seizures at the time of TF was the only factor significantly associated with recurrence.

The average time to recurrence was 19.67 ± 9.32 months after TF.

Discussion

In this study, the recurrence rate of GERD after TF was 5.8%. The following factors were revealed to be significantly associated with recurrence: the presence of convulsive seizures and the absence of a tracheostomy at the time of TF (in univariate analysis), and the presence of convulsive seizures (in multivariate analysis). There were no correlations between recurrence risk factors and GERD severity, surgery-related factors, or postoperative course; this finding suggested that perioperative patient status is strongly associated with GERD recurrence after TF.

The incidence of recurrent GERD in patients who have undergone anti-reflux procedures has been reported to range from 3.2 to 45% [6,7,8], and reoperations for recurrent GERD are undertaken in 3–24% of patients [13, 14]. The mechanism of GERD recurrence is attributed to the recurrence of esophageal hiatal hernia due to mediastinal pull-up of the hilum by increased negative intrathoracic pressure caused by aspiration pneumonia and effortful breathing; and to increased abdominal pressure caused by cough, spasm, muscle tension, and intestinal peristalsis. Compounding factors include deformity of the esophageal hiatus due to progressive lateral gagging, compression of the airway due to scoliosis, and compression of the airway due to the brachiocephalic artery [15,16,17]. The mechanism of GERD recurrence after fundoplication was considered to be the same with both NF and TF. The risk factors for recurrence and prevention of recurrence were also considered to be the same. Although recurrence of GERD due to wrap migration has been reported in NF [18, 19], no such recurrence was observed in this study. In the reconstruction of the angle of His and the anterior wrapping of our TF technique, we always included anchoring sutures with the left and right crura. This is why wrap migration does not easily occur. The recurrence of GERD in this study was due to the recurrence of esophageal hiatal hernia or wrap disruption.

The risk factors for recurrence of GERD that have been reported are neurological impairment (NI) [13], type of procedure performed [20], age of patient at operation [21], concurrent respiratory disease [22], history of congenital esophageal malformations [23], presence of hiatal hernia [24] and the like. It has been reported that age of less than 6 years at surgery is associated with an increased risk of recurrence [16, 25]. However, in this study, there was no significant association between age and recurrence. In addition, it has been reported that fundoplication can be safely performed at age 3 years or younger [26]. Concurrent respiratory disease is a risk factor for recurrence [22, 27]. Our results are consistent with the results of previous studies. In cases of aspiration due to pharyngolaryngeal coordination disorder and repeated aspiration of saliva resulting in aspiration pneumonia, persistently high abdominal pressure is thought to lead to recurrence [27]. Fundoplication is commonly performed in patients with a history of esophageal atresia, however, the success of this surgery is limited, as reflected by an increased rate of redo fundoplication [28]. Our study included five cases of esophageal atresia, but there was only one recurrence, and no significant association was found between esophageal atresia and the risk of recurrence. Our study also included 46 cases of hiatal hernia. Among this group, there were five recurrences but there was no significant association between hiatal hernia and the risk of a recurrence.

Important components of a strategy to decrease the risk of recurrent GERD after fundoplication, include long-term management to improve recurrence factors related to systemic conditions; laryngotracheal separation (LTS) prior to fundoplication [29]; aggressive control of vomiting and retching [25]; and avoidance of postoperative esophageal dilatation [25]. Based on the results of this study, active control of seizures and consideration of surgical indications, including assessment of respiratory status, are important factors in preventing the recurrence of GERD. In this study, 80% of the recurrences occurred within 2 years of surgery, suggesting that special postoperative attention should be given in the first 2 years after surgery. LTS is difficult for patients and caregivers to accept because of the attendant loss of voice [29]. However, LTS has been shown to have dramatic advantages, such as reducing the number of suctioning sessions, eliminating aspiration when eating, and decreasing aspiration pneumonia, thereby reducing the number of hospitalizations and the risk of GERD recurrence [29].

We reported [5] that the TF technique may be an effective and simple treatment for GERD, with few recurrences and without the complications common to NF. Furthermore, we believe that TF would be a better technique if the above management could reduce the recurrence of GERD.

Conclusion

The presence of convulsive seizures and the absence of a tracheostomy at the time of TF were significantly associated with GERD recurrence after TF. Therefore, active control of seizures and consideration of surgical indications, including assessment of respiratory status, are important in preventing the recurrence of GERD after TF.

References

Okada K, Miyako M, Honma S, Wakabayashi Y, Sugihara S, Osawa M (2003) Discharge diagnoses in infants with apparent life-threatening event. Pediatr Int 45:560–563

Ohhama Y, Yamamoto H, Yamada R, Nishi T, Tsunoda A (1991) Nissen fundoplication for severely retarded children suffering from gastroesophageal reflux. J Jpn Soc Pediatr Surg 27:214–218

Iwanaka T, Kanamori Y, Sugiyama M, Komura M, Tanaka Y, Kodaka T, Ishimaru T (2010) Laparoscopic fundoplication for gastroesophageal reflux disease in infants and children. Surg Today 40:393–397

Ru W, Wu P, Feng S, Lai XH, Chen G (2016) Laparoscopic versus open Nissen fundoplication in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pediatr Surg 51:1731–1736

Ishii D, Miyamoto K, Hirasawa M, Miyagi H (2021) Preferential performance of Thal fundoplication for gastroesophageal reflux disease: a single institution experience. Pediatr Surg Int 37:191–196

Ramachandran V, Ashcraft KW, Sharp RJ, Murphy PJ, Snyder CL, Gittes GK, Bickler SW (1996) Thal fundoplication in neurologically impaired children. J Pediatr Surg 31:819–822

Islam S, Teitelbaum DH, Buntain WL, Hirschl RB (2004) Esophagogastric separation for failed fundoplication in neurologically impaired children. J Pediatr Surg 39:287–291

Kubiak R, Spitz L, Kiely EM, Drake D, Pierro A (1999) Effectiveness of fundoplication in early infancy. J Pediatr Surg 34:295–299

McCauley RG, Darling DB, Leonidas JC, Schwartz AM, Leape LL (1978) Esophagrams are useful. Pediatrics 61:503–504

Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA (2004) Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg 240:205–213

Mattei P (2003) Surgical directives pediatric surgery. Philadelphia, USA

Kanda Y (2013) Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software “ezr” for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant 48:452–458

Fonkalsrud EW, Ashcraft KW, Coran AG, Ellis DG, Grosfeld JL, Tunell WP, Weber TR (1998) Surgical treatment of gastroesophageal reflux in children: a combined hospital study of 7467 patients. Pediatrics 101(3 Pt 1):419–422

Graziano K, Teitelbaum DH, McLean K, Hirschl RB, Coran AG, Geiger JD (2003) Recurrence after laparoscopic and open Nissen fundoplication: a comparison of the mechanisms of failure. Surg Endosc 17:704–707

Ishimaru T, Iwanaka T, Kawashima H, Uchida H, Yotsumoto K, Gotoh C, Hamano S (2007) Six cases of recurrence after laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication: causes of recurrence and laparoscopic reoperation. J Jpn Soc Pediatr Surg 43:603–608

Dedinsky G, Vane DW, BIack T, Turner MK, West KW, Grosfeld JL (1987) Complications and reoperation after Nissen fundoplication in children. Am J Surg 153:177-183

Spitz L, Roth K, Kiely EM, Brereton RJ, Drake DP, Milla PJ (1993) Operation for gastro-oesophageal reflux associated with severe mental retardation. Arch Dis Child 68:347–351

Hainaux B, Sattari A, El C, Sadeghi N, Cadière GB (2002) Intrathoracic migration of the wrap after laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication: radiologic evaluation. AJR Am J Roentgenol 178:859–862

Doi T, Ichikawa S, Miyano G, Lane GJ, Miyahara K, Yamataka A (2008) A New Technique for Preventing Wrap Disruption/Migration After Laparoscopic Nissen Fundoplication: An Experimental Study. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 18:179–182

Tuggle D, Tunell W, Hoelzer D, Smith E (1988) The efficacy of Thal fundoplication in the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux: the influence of central nervous system impairment. J Pediatr Surg 23:638–640

Esposito C, Montupet P, Reinberg O (2001) Laparoscopic surgery for gastroesophageal reflux disease during the first year of life. J Pediatr Surg 36:715–717

Kimber C, Kiely EM, Spitz L (1998) The failure rate of surgery for gastrooesophageal reflux. J Pediatr Surg 33:64–66

Kovesi T, Rubin S (2004) Long-term complications of congenital esophageal atresia and/or tracheoesophageal fistula. Chest 126:915–925

Voitk A, Joffe J, Alvarez C, Rosenthal G (1999) Factors contributing to laparoscopic failure during the learning curve for laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication in a community hospital. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 9:243–248

Monawat N, Douglas CB, Ramanath NH, Jeffrey MR, Keith EG, Carroll MH (2007) Risk factors for recurrent gastroesophageal reflux disease after fundoplication in pediatric patients: a case-control study. J Pediatr Surg 42:1478–1485

Fonkalsrud EW, Bustorff-Silva J, Perez CA, Quintero R, Martin L, Atkinson JB (1999) Antireflux surgery in children under 3 months of age. J Pediatr Surg 34:527–531

Oonuma T (2003) Medical approach to improve QOL of children with mental and physical disabilities. Jpn J Pediat 56:997–1004

Pellegrino SA, King SK, McLeod E, Hawley A, Brooks J, Hutson JM, Teague WJ (2018) Impact of Esophageal Atresia on the Success of Fundoplication for Gastroesophageal Reflux. J Pediatr 198:60–66

Takamizawa S, Tsugawa C, Nishijima E, Muraji T, Satoh S, Ise K, Maekawa T (2002) Surgical approach to oropharyngeal dysphagia for neurologically impaired children: Laryngotracheal separation for aspiration pneumonia remaining after fundoplication. Jpn J Pediat Pulmonol 13:20–25

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing. This work was supported by a grants-in-aid of The Ishidsu Shun Memorial Scholarship, Japan.

Funding

No funding has been received for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest associated with this manuscript.

Ethical approval

The Asahikawa Medical University Research Ethics Committee approved this study (Permit no. 20138). All the procedures performed involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Clinical Research Center, Asahikawa Medical University, Japan and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

The authors hereby confirm that informed consent was obtained from all the individual patients included in this study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ishii, D., Miyagi, H. & Hirasawa, M. Risk factors for recurrent gastroesophageal reflux disease after Thal fundoplication. Pediatr Surg Int 37, 1731–1735 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00383-021-05001-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00383-021-05001-1