Abstract

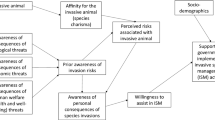

Invasive mammals threaten agriculture, biodiversity, and community health. Yet many landholders fail to engage in control activities recommended by experts. We surveyed a representative sample of 731 Western Australian rural landholders. The survey assessed landholders’ participation in a range of activities to control invasive mammals, as well as their capabilities, opportunities, and motivation for engaging in such activities. We found that over half of our respondents had not participated in any individual or group activities to control invasive mammals during the previous 12 months. Using latent profile analysis, we identified six homogeneous subgroups of nonparticipating landholders, each with their distinct psycho-graphic profiles: Unaware, Unskilled, and Unmotivated, Aware but Unskilled and Doubtful, Unskilled and Time Poor, Disinterested, Skilled but Dismissive, and Capable but Unmotivated. Our results indicate that engagement specialists should not treat nonparticipating landholders as a single homogeneous group. Nonparticipators differ considerably in terms of their capabilities, opportunities, and motivations, and require targeted engagement strategies informed by these differences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Feral cats are not yet listed in the Act. However the Western Australian Environmental Minister endorsed the National declaration of feral cats as pests in 2015, paving the way for this species to be listed in the near future

As the segment Aware but Unskilled and Doubtful only contained a small number of individuals, generalizations of this group beyond this study should be done with caution.

References

Atherley KM (2006) Sport, localism and social capital in rural Western Australia. Geogr Res 44:348–360. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-5871.2006.00406.x

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2016) Census of population and housing basic community profiles, Cat. no. 2001.0. https://quickstats.censusdata.abs.gov.au/census_services/getproduct/census/2016/quickstat/509?opendocument. Accessed April 30 April 2019

Ballard G (ed.) (2006) Social drivers of the invasive animal control. In: Proceedings of the Invasive Animal CRC Workshop, Adelaide. Invasive Animal Cooperative Research Centre, Canberra, 26th–27th July 2006

Braysher M (2017) Managing Australia’s pest animals. A guide to strategic planning and effective management. CSIRO Publishing, Canberra

Buckley R, Sander N, Ollenburg C, Warnken J (2006) Green change: inland amenity migration in Australia. In: Moss LAG (ed) The amenity migrants: seeking and sustaining mountains and their cultures. CABI Publishing, Cambridge, p 278–298

Byerly H, Balmford A, Ferraro PJ, Wagner CH, Palchak E, Polasky S et al. (2018) Nudging pro‐environmental behavior: evidence and opportunities. Front Ecol Environ 16:159–168. https://doi.org/10.1002/fee.1777

Cialdini RB, Demaine LJ, Sagarin BJ, Barrett DW, Rhoads K, Winter PL (2006) Managing social norms for persuasive impact. Soc Influence 1:3–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/15534510500181459

Cohen J (1988) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. L. Erlbaum Associates, Hillsdale, N.J.

Coleman MJ, Sindel BM, Stayner RA (2017) Effectiveness of best practice management guides for improving invasive species management: a review. Rangeland J 39:39–48. https://doi.org/10.1071/RJ16087

Damasio, AR (1994) Descartes’ error: Emotion, reason, and the human brain. Putnam Publishing, New York, US

Darnton A (2008) GSR behaviour change knowledge review. Practical guide: an overview of behaviour change models and their uses. Government Social Research Unit, HM Treasury, London

Emtage N, Herbohn J (2012) Assessing rural landholders diversity in the Wet Tropics region of Queensland, Australia in relation to natural resource management programs: a market segmentation approach. Agric Syst 110:107–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2012.03.013

Emtage N, Herbohn J, Harrison S (2007) Landholder profiling and typologies for natural resource–management policy and program support: potential and constraints. Environ Manag 40:481–492. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-005-0359-z

Fleming PJS, Allen LR, Lapidge SJ, Robley A, Saunders GR, Thomson PC (2006) A strategic approach to mitigating the impacts of wild canids: proposed activities of the Invasive Animals Cooperative Research Centre. Aust J Exp Agric 46:753–762

Ford-Thompson AES, Snell C, Saunders G, White PCL (2012) Stakeholder participation in management of invasive vertebrates. Conserv Biol 26:345–356. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2011.01819.x

Gardner GT, Stern PC (2002) Environmental problems and human behavior, 2nd edn. Pearson Custom Publishing, Boston

Guerin LJ, Guerin TF (1994) Constraints to the adoption of innovations in agricultural research and environmental management: a review. Aust J Exp Agr 34:549–571

Halvorson K, Rach M (2012) Content strategy for the web, 2nd edn. New Riders, Berkley, CA

Hernandez SM, Loyd KAT, Newton AN, Carswell BL, Abernathy KJ (2018) The use of point-of-view cameras (Kittycams) to quantify predation by colony cats (Felis catus) on wildlife. Wildlife Res 45:357–365. https://doi.org/10.1071/WR17155

Hine DW, McLeod LJ, Driver AB (2018) Designing behaviour change interventions for invasive animal control: a practical guide. Invasive Animal Cooperative Research Centre, Canberra

Hine DW, Phillips WJ, Driver AB, Morrison M (2017) Audience segmentation and climate change communication. Oxford handbook of climate change communication. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK

Hine DW, Please P, McLeod L, Driver A (2015) Behaviourally effective communications for invasive animals management: a practical guide. Invasive Animal Cooperative Research Centre, Canberra

Hine DW, Sharp T, Driver AB (2019) Using audience segmentation and targeted social marketing to improve landholder management of invasive animals. In: Martin P, Alter T, Hine D & Howard T (eds), People managing pests: modern theories and practices for effective community-based control of invasive species. CSIRO Publishing, Canberra

Howard TM, Thompson LJ, Frumento P, Alter T (2018) Wild dog management in Australia: an interactional approach to case studies of community-led action. Hum Dim Wildlife 23:242–256. https://doi.org/10.1080/10871209.2017.1414337

IBM (2017) IBM SPSS statistics for windows version 25. IBM Corp, Armonk, NY

Ison R, Russell D (2000) Agricultural extension and rural development. Breaking out of traditions. Cambridge University Press, UK

Kahneman D (2013) Thinking, fast and slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York, NY

Kalnicky EA, Brunson MW, Beard KH (2019) Predictors of participation in invasive species cpontrol activities depend on prior experience with the species. Environ Manag 63:60–68. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-018-1126-2

Klepeis P, Gill N, Chisholm L (2009) Emerging amenity landscapes: invasive weeds and land subdivision in rural Australia. Land Use Policy 26:380–392. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2008.04.006

Lo Y, Mendell NR, Rubin DB (2001) Testing the number of components in a normal mixture. Biometrika 88:767–778

Low Choy D, Harding J (2010) UMCCC Peri-urban Weed Management Study. Exploring agents of change to peri-urban weed management. Land & Water Australia, Canberra

McGowan C (2011) Women in agriculture. In: Pannell D, Vanclay F (eds) Changing land management: adoption of new practices by rural landholders. CSIRO Publishing, Collingwood, Vic, p 141–152

McKenzie-Mohr D (2011) Fostering sustainable behaviour: An introduction to community-based social marketing, 3rd edn. New Society Publishers, BC, Canada

McLeod LJ, Driver AB, Bengsen AJ, Hine DW (2017) Refining online communication strategies for domestic cat management. Anthrozoos 30:635–649. https://doi.org/10.1080/08927936.2017.1370237

McLeod LJ, Hine DW, Please P (2019) Using human behaviour change strategy to improve the management of invasive species. In: Martin P, Alter D, Hine D & Howard T (eds), People managing pests: modern theories and practices for effective community-based control of invasive species. CSIRO Publishing, Canberra

McLeod LJ, Hine DW, Please P, Driver AB (2015) Applying behavioral theories to invasive animal management: towards an integrated framework. J Environ Manag 161:63–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2015.06.048

McLeod R (2016) Cost of pest animals in NSW and Australia, 2013–14. Report prepared for the NSW Natural Resources Commission, eSYS Development Pty Ltd.

Michie S, Atkins L, West R (2014) The behaviour change wheel. A guide to designing interventions. Silverback Publishing, UK

Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M, Abraham C, Francis J, Hardeman W et al. (2013) The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann Behav Med 46:81–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-013-9486-6

Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R (2011) The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci 6:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-6-42

Miller KK (2009) Human dimension of wildlife population management in Australasia – history, approaches and directions. Wildlife Res 36:48–56. https://doi.org/10.1071/WR08006

Mitchell J, Dorney W, Mayer R, McIlroy J (2009) Migration of feral pigs (Sus scrofa) in rainforests of north Queensland: fact or fiction? Wildlife Res 36:110–116. https://doi.org/10.1071/WR06066

Morrison M, Durante J, Greig J, Ward J, Oczkowski E (2012) Segmenting landholders for improving the targeting of natural resource management expenditures. J Environ Plan Man 55:17–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2011.575630

Murnane RJ, Willet JB (2010) Methods matter: improving causal inference in educational and social science research. Oxford University Press, New York, NY

Muthén LK, Muthén BO (2014) MPlus 7.0. Muthén & Muthén, Los Angeles, CA

Niemiec RM, Ardoin NM, Wharton CB, Asner GP (2016) Motivating residents to combat invasive species on private lands: social norms and community reciprocity. Ecol Soc 21:30–40. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-08362-210230

Outwater M (2011) Telephone surveys. In: Lavrakas PJ (ed) Encyclopedia of survey research methodsSage Publications, Thousand Oaks, pp 885–886

Pint of Science (2019) Out of the lab and into the local. https://pintofscience.com.au/ Accessed 30 April 2019

Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC, Norcross JC (1992) In search of how people change. Applications to addictive behavior. Am Psychol 47:1102–1114. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.47.9.1102

Ramaswamy V, Desarbo WS, Reistein DJ, Robinson WT (1993) An empirical pooling approach for estimating marketing mix elasticities with PIMS data. Market Sci 12:103–124

Salmon O, Brunson M, Kuhns M (2006) Benefit-based audience segmentation: a tool for identifying nonindustrial private forest (NIPF) owner education needs. J For 104:419–425. https://doi.org/10.1093/jof/104.8.419

Schultz PW (2014) Strategies for promoting proenvironmental behavior. lots of tools but few instructions. Eur Psychol 19:107–117. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000163

Schwartz G (1978) Estimating the dimension of a model. Ann Stat 6:461–464

Sewell AM, Hartnett MK, Gray DI, Blair HT, Kemp PD, Kenyon PR et al. (2017) Using educational theory and research to refine agricultural extension: affordances and barriers for farmers’ learning and practice change. J Agr Educ Ext 23:313–333. https://doi.org/10.1080/1389224x.2017.1314861

Southwell D, Boero V, Mewett O, McCowen S, Hennecke B (2013) Understanding the drivers and barriers to participation in wild canid management in Australia: implications for the adoption of a new toxin, para-aminopropiophenone. Int J Pest Manag 59:35–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/09670874.2012.744493

Subroy V, Rogers AA, Kragt ME (2018) To bait or not to bait: a discrete choice experiment on public preferences for native wildlife and conservation management in Western Australia. Ecol Econ 147:114–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2017.12.031

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the funding support through the Royalties for Regions program and the Invasive Animals Cooperative Research Centre (IA CRC). We would like to thank the Western Australian Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development for their assistance throughout the project, and for supplying Fig. 1. We would also like to thank Myriad Research and Thinkfield for their assistance in the survey development and execution, all the landholders who took the time to be involved, and the two anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments on the first draft of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of New England (Approval No HE16_107), and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix 1– Copy of Survey Questions

Appendix 1– Copy of Survey Questions

1. Is your property mainly used for (read out)

Cattle production | 1 | Mixed farming | 5 | Lifestyle | 9 |

Dairy | 2 | Dryland cropping | 6 | Residential | 10 |

Sheep production | 3 | Irrigated cropping | 7 | Other: | 11 |

Other livestock: | 4 | Boutique enterprise: | 8 | Specify___________ | |

Specify___________ | Specify___________ |

2. Is your property your main source of income? | Yes | 1 | No | 2 |

3. How long have you lived on your property? | _____________ years | |||

4. To what extent do you consider … (from list below) to be a problem on your property—on a scale of 1 to 5, where 5 = a very severe problem, 4 = severe problem, 3 = a moderate problem, 2 = minor problem, 1 = not a problem at all?

Not a problem | Minor problem | Moderate problem | Severe problem | Very severe problem | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

a. Wild dogs | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

b. Foxes | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

c. Feral cats | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

d. Feral pigs | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

e. Rabbits | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

5. In the past how often have you conducted individual activities to manage … (from list below) on your property—on a scale of 1 to 5, where 5 = very often, 4 = often, 3 = sometimes, 2 = rarely, 1 = never?

Never | Rarely | Sometimes | Often | Very often | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

a. Wild dogs | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

b. Foxes | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

c. Feral cats | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

d. Feral pigs | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

e. Rabbits | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

6. In the past how often have you participated in organized group activities with neighbors and other community members to manage … (from list below)

Never | Rarely | Sometimes | Often | Very often | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

a. Wild dogs | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

b. Foxes | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

c. Feral cats | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

d. Feral pigs | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

e. Rabbits | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

7. People give many reasons why they do or don’t conduct pest animal management activities. I am going to read out a list of these reasons. Please tell me to what extent to you agree or disagree with each statement—on a scale of 1 to 5, where 5 = strongly agree and 1 = strongly disagree.

Disagree | Agree | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

a. I do not know the best methods to control pest animals on my property | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | NA |

b. I do not have the skill to carry out pest animal management activities correctly | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | NA |

c. I do not have the time to carry out pest animal management activities when they are required | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | NA |

d. It is too expensive to conduct pest animal management activities | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | NA |

f. Most of my neighbors do not control pest animals on their properties | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | NA |

g. In my community, landholders are expected to control pest animals on their properties | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | NA |

h. Managing pest animals will not improve the profitability of my enterprise | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | NA |

i. Managing pest animals will not improve the long-term sustainability of my property | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | NA |

j. I do not think that the impacts of animals labeled as pests are as bad as they are made out to be | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | NA |

k. I believe pest animal control methods are inhumane | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | NA |

l. I seem to be wasting my time as the pest animals always come back | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | NA |

m. Controlling pests and caring for my land are inseparable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | NA |

n. I control pest animals for the recognition I get for being a good land manager | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | NA |

And just to finish off.

8. Can I just check your age range – are you | 18–29 | 1 | 50–59 | 4 | |||

30–39 | 2 | 60–69 | 5 | ||||

40–49 | 3 | 70+ | 6 | ||||

declined | 7 | ||||||

9. Gender (record automatically) | Male 1 | Female 2 | |||||

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

McLeod, L.J., Hine, D.W. Using Audience Segmentation to Understand Nonparticipation in Invasive Mammal Management in Australia. Environmental Management 64, 213–229 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-019-01176-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-019-01176-5