Abstract

Western juniper (Juniperus occidentalis subsp. occidentalis) range expansion into sagebrush steppe ecosystems has affected both native wildlife and economic livelihoods across western North America. The potential listing of the greater sage-grouse (Centrocercus urophasianus) under the U.S. Endangered Species Act has spurred a decade of juniper removal efforts, yet limited research has evaluated program effectiveness. We used a multi-objective spatially explicit model to identify optimal juniper removal sites in Northeastern California across weighted goals for ecological (sage-grouse habitat) and economic (cattle forage production) benefits. We also extended the analysis through alternative case scenarios that tested the effects of coordination among federal agencies, budgetary constraints, and the use of fire as a juniper treatment method. We found that sage-grouse conservation and forage production goals are somewhat complementary, but the extent of complementary benefits strongly depends on spatial factors and management approaches. Certain management actions substantially increase achievable benefits, including agency coordination and the use of prescribed burns to remove juniper. Critically, our results indicate that juniper management strategies designed to increase cattle forage do not necessarily achieve measurable sage-grouse benefits, underscoring the need for program evaluation and monitoring.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Over the last 130 years, western juniper (Juniperus occidentalis subsp. occidentalis) populations have expanded into large areas of sagebrush steppe habitat across western North America (Miller et al. 2000; Davies et al. 2011). A mix of environmental and managerial factors in the landscape have facilitated this range expansion, including fire suppression (Miller et al. 2000), fuel reductions from grazing (Burkhardt and Tisdale 1976; Miller and Rose 1995), and increased atmospheric carbon dioxide (Soulé et al. 2004).

In sagebrush ecosystems, juniper range expansion (Fig. 1a) threatens both native wildlife and agricultural productivity (Miller et al. 2000; Bates 2005; Noson et al. 2006). For example, the conversion of sagebrush steppe to juniper woodland negatively affects greater sage-grouse (Centrocercus urophasianus, Fig. 1b) by reducing sagebrush cover and the associated plants and insects that comprise the birds’ diet (Crawford et al. 2004; Doherty et al. 2008; Baruch-Mordo et al. 2013). In addition, changes in the geographic range and density of juniper can affect forage for cattle. In the Great Plains region, livestock production has dropped by 75 % in areas where the closely related eastern red-cedar (Juniperus virginiana) has encroached into grasslands (Twidwell et al. 2013).

To address the impact of western juniper expansion on greater sage-grouse and sustainable grazing, the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) launched the Sage-Grouse Initiative (SGI) in 2010 (NRCS 2012a). SGI funds juniper removal and sagebrush steppe habitat restoration projects on public and private lands with the goal of simultaneously improving environmental and economic objectives (NRCS 2012b). Despite a decade of initiatives and funding, as well as the pending listing decision for the greater sage-grouse (hereafter sage-grouse) under the U.S. Endangered Species Act (USFWS 2010), few studies have assessed the implementation of juniper removal strategies (Baruch-Mordo et al. 2013). Sage-grouse habitat restoration is often promoted as complementary with cattle grazing (NRCS 2012a), but the degree of complementarity has not been evaluated in the scientific literature.

Multi-objective management of natural resources seeks to balance human demands, environmental preservation, and future resource availability (Schmoldt 2001). Decision-makers must often prioritize among different goals by evaluating the economic and environmental benefits of various actions. Software tools such as Zonation (Williams et al. 2005) and Marxan (Possingham et al. 2000) can support decision-making for landscape-level conservation planning, but limited resources and learning curves often restrict extensive use of such tools by land managers. Additionally, these off-the-shelf programs may not be applicable to certain management tasks due to issues of model formulation (cost minimization or data structure) or focus (marine reserves, land parcels, etc.). Simpler, more adaptable tools can allow decision-makers to more rapidly assess strategies for conservation and resource management.

We developed a spatially explicit decision model using multi-objective optimization to assess juniper management strategies for (1) sage-grouse habitat restoration and (2) forage production for cattle. Our primary goal was to assess whether juniper management programs designed to improve sage-grouse habitat can yield forage production benefits and vice versa. Although land availability and owner willingness currently drive site selection for SGI projects, we explored how land managers could prioritize locations based on their suitability for one or both objectives. Our research provides a timely evaluation of SGI management strategies and contributes to the growing collection of integrated modeling tools for conservation of threatened species and resource management.

Methods

We analyzed optimal budget allocations for juniper removal across a region of the Modoc Plateau (Fig. 2) using a simple and novel algorithm that adapted several optimization approaches. We used a ranking procedure to sequentially select the best available sites for treatment (DeVore and Temlyakov 1996) and developed a procedure for incorporating multiple goals with different units derived from the “constraint method” in linear programming (Haimes 1970). The analysis optimized juniper removal decisions across a landscape, assessing costs and benefits to identify the best areas for treatment. We then extended the analysis to include several alternative cases. The section below describes: (1) methods for determining benefits and costs, (2) model formulation and implementation, and (3) alternative analysis cases.

Distribution of western juniper (Juniperus occidentalis subsp. occidentalis, shown in green) modified from Miller et al. 2005. Inset map indicates study region, with blue 2000 × 2000 m grid cells representing “decision units” considered in the model and the location of the Greenleaf Power Plant in Wendel, CA (red star)

Benefits of Treatment: Forage Production

We obtained herbaceous vegetation and juniper canopy cover data from Coultrap et al. (2008) for 97 circular plots (45 m diameter) in Modoc, Lassen, and Siskiyou counties. Based on a comparison of sites with intact western juniper communities and those where juniper was removed, Coultrap et al. (2008) reported that juniper removal led to increased grass cover, higher herbaceous productivity, and less bare ground. The authors chose study plots that: (1) were representative of soil and vegetation types in the area, (2) exhibited variable juniper canopy cover, (3) had not been grazed, and (4) allowed for comparison of treated sites (juniper removed) and adjacent untreated sites. Mean juniper canopy cover across the 97 sites was 12 % (range 0–74 %).

For each plot location, we assessed a range of environmental and geophysical variables as potential predictors of forage production, including date of onset of the frost-free period, temperature difference between the average warmest and coldest month, soil properties, slope, and elevation (Appendix A1). We obtained juniper canopy cover data from an NRCS analysis of aerial photography (Falkowski and Evans 2012). We derived downscaled climate data from the PRISM dataset (PRISM Climate Group 2012) using the ClimateWNA tool (Wang et al. 2011). We obtained soil and topographic information from the NRCS STATSGO2 database (NRCS 2012c) and ASTER DEM data (EOSDIS 2009), respectively. Adopting the common log-linear regression specification (Johnson et al. 1999), we used these environmental and geophysical variables to estimate the relationship between forage production and juniper canopy cover in the original plots from the Coultrap et al. (2008) dataset. We then applied this function to estimate potential increases in forage production following complete juniper removal for sites across the entire study region (Appendix A1). While we use the term “forage” to refer to all herbaceous plant material, we recognize that not all herbaceous plants provide equal nutritional benefit for cattle.

Benefits of Treatment: Sage-grouse

We assessed benefits of juniper treatment to sage-grouse populations using a spatially explicit model to predict the relative probability of sage-grouse occurrence based on density of breeding birds observed near leks. Leks are ideal locations for space use analyses because they are hubs for nesting (Autenrieth 1985; Connelly et al. 2004) and are generally centered among seasonal use areas (Coates et al. 2013).

To calculate a “breeding density index”, we obtained lek coordinates and count data (number of males attending leks) from the California Department of Fish and Wildlife and the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife. We used a kernel density estimator (Silverman 1986) with smoothing parameters estimated using likelihood based cross-validation to create a utilization distribution (“UD”, Appendix A2). Given the distribution and density of documented animal occurrences, UDs provide an approximation of sage-grouse space use (Coates et al. 2013). We then used the UD to calculate a “dispersal index” representing the probability of sage-grouse occurrence in each landscape cell given complete juniper removal within that cell. For additional detail on methodologies used to assess sage-grouse benefits, see Appendix A2.

Costs of Treatment

To collect data on treatment costs as well as decision-making heuristics for treatment method selection, we interviewed stakeholders with firsthand experience implementing juniper treatment projects on the Modoc Plateau (UC Davis IRB #420715-1). Respondents included representatives from private consulting firms, federal agencies, and cooperative extension. The aggregated data from these interviews provided us with a range of thresholds to inform treatment method selection, including the maximum juniper canopy cover and slope for various treatment methods, as well as the per hectare cost of using various methods (Tables A2 and A3).

We considered the two most commonly used methods of juniper removal: hand treatment, which involves felling trees with chainsaws in regions of low juniper density, and mechanical treatment, which uses heavy machinery to fell and pile trees and is most effective at high juniper density (Table A3). We did not allow treatment in: (1) areas with >30 % slope (averaged at the one hectare scale) due to reported concerns about accessibility and post-treatment erosion or (2) areas with >30 % juniper cover due to sparse understory cover and a depauperate seed bank (Miller et al. 2005). Based on interview responses, we assigned hand treatment a fixed cost of $100/ha and mechanical treatment a cost of $300/ha (Table A2).

To compare different treatment regimes, we conducted analyses assuming a budget of $5 million for the study region. This value roughly corresponds to SGI funding allocated to projects on the Modoc Plateau ($5.9 million) during the 2011 fiscal year (NRCS 2012b). Because our study region does not include the entire Modoc Plateau, we rounded down the SGI budget to obtain a more realistic funding value for the area.

Model Implementation

The model is a simplified Greedy Algorithm (DeVore and Temlyakov 1996) implemented in the R Statistical Environment (R Development Core Team 2014). Each cell in the grid has attributes for treatment cost, treatment benefit for sage-grouse habitat, and treatment benefit for forage production. The model assumes that when any given cell is treated, all trees are removed within the cell. The algorithm calculates the weighted cost-effectiveness (\(Z_{i}\)) for a cell \(i\) as the total weighted benefits of treating a cell divided by the cost (\(C_{i}\)) of treating that cell:

Each cell has an associated benefit from treatment for forage production (\(B_{{i_{\text{forage}} }}\)) and sage-grouse habitat (\(B_{{i_{\text{habitat}} }}\)). The forage-to-habitat conversion factor (\(f\)) creates comparable values between the two goals:

In Eq. 2, the maximum forage benefit (\(B_{{{ \hbox{max} }_{\text{forage}} }}\)), which is measured in kilograms, is the benefit achievable within a given budget when only maximizing forage production. Similarly, the maximum habitat benefit (\(B_{{{ \hbox{max} }_{\text{habitat}} }}\)) is the benefit achievable within the same budget when only maximizing habitat. Sage-grouse habitat benefits are measured as a percentage of the total benefits possible if all sage-grouse habitat improvements in the study region were made. Finally, the two weights are applied as percentages:

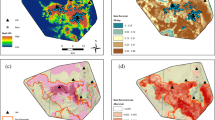

For each case, we ran the algorithm multiple times, each with different values of \(W_{\text{forage}}\) and \(W_{\text{habitat}}\) ranging from 0 to 1 and 1 to 0, respectively. The algorithm calculates the weighted cost-effectiveness of each cell based on the given weighting factors, ranks the cells from high to low based on weighted cost-effectiveness, and iteratively selects to treat the most cost-effective untreated cell until the budget limit is reached. The result is a spatially explicit map of treated cells and total estimated benefits for both sage-grouse and livestock that corresponds to a given budget (Fig. 3). Our study region consisted of 877,200 ha, divided into 2193 treatment sites of 4 km2 each.

Alternative Cases

We carried out several alternative cases that either introduced other factors or relaxed assumptions in our baseline model about a key ecological, economic, or administrative condition (Table A3). Our alternative cases, detailed in Appendix section A.4, were: (1) degree of coordination among land management groups, (2) sale of chipped juniper biomass as an offset to treatment cost, (3) variable budget constraints, and (4) fire as a juniper treatment method.

Results

Our results suggest that sage-grouse habitat and forage production benefits: (1) are sometimes complementary, (2) exhibit decreasing-returns-to-scale, and (3) depend on landscape characteristics. There are several potential relationships between the two goals, illustrated in Fig. 4. These include a hypothetical 1:1 tradeoff in sage-grouse habitat and forage production (straight line) and the model results (labeled curve) (Fig. 4). We refer to these curves as efficiency frontiers (Polasky et al. 2008). Each curve shows the maximum production for a given budget, while the concavity of the model results curve indicates tradeoffs in the two goals with decreasing-returns-to-scale (Fig. 4). In this case, decreasing-returns-to-scale refers to the scenario in which juniper treatment increases by a factor m, but outputs (either sage-grouse or forage production benefits) increase by less than m. Alternatively, moving away from the intersection between the labeled curve and the y-axis, an initial m reduction in forage production results in greater than m gains in sage-grouse habitat restoration (Fig. 4). For each successive m reduction in forage production, the corresponding increase in sage-grouse benefits gets smaller.

Tradeoffs between prioritizing forage production and sage-grouse habitat restoration, as illustrated by the efficiency frontier for the baseline scenario. The straight line indicates the frontier that would exist if forage production and sage-grouse habitat had a perfect tradeoff (i.e., if choosing one goal achieved none of the other). The baseline efficiency frontier lies above the perfect tradeoff line, suggesting some synergy between forage production and sage-grouse habitat goals. The dashed line connecting the baseline efficiency frontier to the x-axis shows the amount of forage production gained when sage-grouse goals are prioritized 100 %. Completely prioritizing forage production achieves about 1 % of sage-grouse habitat restoration, but is not visible on the graph

Juniper removal can benefit both sage-grouse habitat and cattle forage production, but outcomes depend on prioritization of goals. Juniper removal policies that prioritize forage production (i.e., selecting sites with the highest potential forage yield) result in little to no benefit for sage-grouse. Conversely, when juniper removal decisions are directed to improve sage-grouse habitat, substantial forage production benefits can accrue. In this case, tradeoffs between the two goals vary depending on the degree to which management objectives prioritize sage-grouse versus forage production. For instance, as the percentage of sage-grouse habitat restored increases, the relative gain in forage production declines (Fig. 5). These tradeoffs are linked directly to the spatial distribution of benefits on the landscape. Because each treatment site differs in terms of its potential benefit to sage-grouse and forage production goals, shifting prioritization of the two goals changes the network of sites selected for treatment on the landscape. In our study region, the two extremes of goal prioritization (100 % emphasis on sage-grouse goals versus 100 % emphasis on forage production goals) have entirely different selections of treatment sites (Fig. 5).

Baseline efficiency frontier showing spatial configuration of treated juniper at various weightings of sage-grouse habitat and forage production. Changing the prioritization of sage-grouse habitat restoration and forage production goals substantially affects the sites selected for juniper removal, shown in the three inset graphs. Complete sage-grouse habitat prioritization and complete forage production prioritization have entirely different selections of treatment sites

Alternative Model Cases

Our results suggest that agency coordination, budgetary constraints, and fire affect the amount of achievable benefits for ranching and sage-grouse conservation goals. However, the shape of the curves, which indicates the relationship between the two objectives, was constant (Fig. 6). We present the results for each case below.

Tradeoff curves for alternative analysis cases of a varying the level of federal agency coordination in treatment; b including chipped juniper biomass as a resource to offset management costs; c adjusting budgetary constraints; and d including fire as a treatment method. In each graph, the baseline case is shown in black. An outward shift in the curve away from the origin indicates that more benefits can be achieved. In the “Budget Constraints” panel, the vertical line shows a target of 25 % sage-grouse habitat restoration, which is only achievable at two of the budgets shown

Alternative Case 1: Lack of Agency Coordination

The degree of coordination among managing agencies substantially affected achievable benefits. Notably, when efforts to remove juniper are uncoordinated, the efficiency frontier decreases substantially in comparison with the baseline model (Fig. 6a) and reduces the potential benefits of juniper removal for the two goals.

Alternative Case 2: Biomass as an Additional Resource

We found that in 321 sites (out of 2193) the sale of wood chips to a local biomass plant (Fig. 2) could subsidize the cost of treatment by amounts ranging from $427 to $108,953. Although the biomass market can reduce treatment costs for some potential sites, this cost reduction (mean = $35,891) is not large enough compared to the cost of treatment (mean = $139,945) to allow for the treatment of additional sites. For this reason, the efficiency frontier does not expand in comparison with the baseline (Fig. 6b).

Alternative Case 3: Variable Budgets

Potential benefits of juniper removal changed in proportion to the available budget (Fig. 6c). A larger budget expanded the frontier of possible benefits, allowing for more sage-grouse habitat conservation as well as greater forage production. In comparison, smaller budgets reduced the potential benefits for both goals.

Alternative Case 4: Fire as a Treatment Method

When we included prescribed burns as a possible treatment option, the efficiency frontier expanded substantially compared to the baseline model (Fig. 6d). Because fire is a less costly juniper removal method, a much larger area could be treated for a given budget, which in our model yielded significantly greater forage production and sage-grouse habitat restoration.

Discussion

For land managers in Northeastern California, multi-objective management of western juniper requires thoughtful prioritization of goals. Our results indicate that sage-grouse conservation and forage production goals may be complementary in some scenarios, but not without tradeoffs. Critically, prioritizing juniper removal decisions to improve forage production only produces a small increase in sage-grouse benefits. This tradeoff is directly related to the spatial distribution of benefits across the study region. Potential sage-grouse benefits are highest on land parcels with relatively dense juniper cover that are located in close proximity to lek locations. These benefits decay rapidly with increasing distance from a lek. Thus, treating a land parcel that is geographically isolated from lek locations would confer some amount of forage production benefits but no sage-grouse benefits. Overall, the model results indicate that juniper removal projects selected solely for rangeland benefits will not always benefit sage-grouse.

Our model also suggests that institutional constraints substantially alter potential benefits of juniper removal. While prescribed burns may be the most cost-effective method of juniper removal in California and many parts of the western U.S., bureaucratic and legal restrictions that seek to ensure safety may limit the use of this treatment option (Brunson and Evans 2005). Even in the absence of institutional constraints, it is unclear whether the use of prescribed fire would benefit sage-grouse. At least two long-term studies have reported negative effects of fire on sage-grouse nesting habitat (Nelle et al. 2000) and male lek attendance (Connelly et al. 2000), suggesting that land managers should exercise caution when using prescribed burns as a habitat restoration strategy.

Coordination among federal agencies working to control juniper can also increase achievable benefits for sage-grouse habitat improvement and forage production. However, the budgetary allocations that flow through different federal and state agencies can reduce incentives to cooperate in landscape-level approaches to juniper removal. While the SGI is novel in its broad coalition of public and private partners, project funding is often still allocated separately.

At present, budgets for juniper removal through the SGI are relatively large (NRCS 2012a). Although our model results indicate that sage-grouse and forage benefits scale with budget, selected targets for sage-grouse or forage might not be achievable at all budgets. For instance, a total program budget of $2.5 million is insufficient to achieve a goal of 25 % of the total benefits for sage-grouse populations (Fig. 6c). This could have considerable implications if biologically relevant sage-grouse benefits do not accrue without a minimum level of spending. Below this budget amount, only sub-optimal sites with limited potential benefit for sage-grouse would be restored. Such outcomes could result either from implementation issues or from overall budgetary reductions.

At a regional scale, our analysis shows that large scale initiatives can effectively manage juniper for both sage-grouse and cattle ranching goals. However, because the balance of prioritization between the two goals determines the range of potential shared benefits and overall complementarity, management may not meet multiple goals unless it is explicitly designed to do so. To avoid funding projects that have little or no benefit for sage-grouse, careful oversight and post-treatment evaluation are necessary.

References

Autenrieth R (1985) Sage grouse life history and habitat management. Rangeland Fire Effects: A Symposium. U.S. Bureau of Land Management, University of Idaho, Boise

Baruch-Mordo S, Evans JS, Severson JP, Naugle DE, Maestas JD, Kiesecker JM, Falkowski MJ, Hagen CA, Reese KP (2013) Saving sage-grouse from the trees: a proactive solution to reducing a key threat to a candidate species. Biol Conserv 167:233–241

Bates JD (2005) Herbaceous response to cattle grazing following juniper cutting in Oregon. Rangel Ecol Manag 58:225–233

Brunson MW, Evans J (2005) Badly burned? Effects of an escaped prescribed burn on social acceptability of wildland fuels treatments. J For 103:134–138

Burkhardt JW, Tisdale E (1976) Causes of juniper invasion in southwestern Idaho. Ecology 57:472–484

Coates PS, Casazza ML, Blomberg EJ, Gardner SC, Espinosa SP, Yee JL, Wiechman L, Halstead BJ (2013) Evaluating greater sage-grouse seasonal space use relative to leks: implications for surface use designations in sagebrush ecosystems. J Wildl Manag 77:1598–1609

Connelly JW, Reese KP, Fischer RA, Wakkinen WL (2000) Response of a sage grouse breeding population to fire in southeastern Idaho. Wildl Soc Bull 28:90–96

Connelly JW, Knick ST, Schroeder MA, Striver SJ (2004) Conservation assessment of greater sage-grouse and sagebrush habitats. Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies, Cheyenne

Coultrap DE, Fulgham KO, Lancaster DL, Gustafson J, Lile DF, George MR (2008) Relationships between western juniper (Juniperus occidentalis) and understory vegetation. Invasive Plant Sci Manag 1:3–11

Crawford JA, Olson RA, West NE et al (2004) Ecology and management of sage-grouse and sage-grouse habitat. Rangel Ecol Manag 57:2–19

Davies KW, Boyd CS, Beck JL, Bates JD, Svejcar TJ, Gregg MA (2011) Saving the sagebrush sea: an ecosystem conservation plan for big sagebrush plant communities. Biol Conserv 144:2573–2584

DeVore RA, Temlyakov VN (1996) Some remarks on greedy algorithms. Adv Comput Math 5:173–187

Doherty KE, Naugle DE, Walker BL, Graham JM (2008) Greater sage-grouse winter habitat selection and energy development. J Wildl Manag 72:187–195

Earth Observing System Data and Information System (EOSDIS). 2009. Earth Observing System ClearingHOuse (ECHO)/Reverb, Version 10.X [online application]. Greenbelt, MD: EOSDIS, Goddard Space Flight Center (GSFC) National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). http://reverb.earthdata.nasa.gov

Falkowski MJ, Evans J (2012) Mapping conifer trees in sage grouse habitat using spatial wavelet analysis: a tool for prioritizing treatment of conifer encroachment. NRCS Completion Report under 68-7482-10-525

Haimes YY (1970) The integration of system identification and system optimization. Dissertation. University of California, Los Angeles

Johnson P, Gerbolini A, Ethridge D et al (1999) Economics of redberry juniper control in the Texas rolling plains. J Range Manag 52:569–574

Miller RF, Rose JA (1995) Historic expansion of Juniperus occidentalis (western juniper) in southeastern Oregon. West North Am Nat 55:37–45

Miller RF, Svejcar TJ, Rose JA (2000) Impacts of western juniper on plant community composition and structure. J Range Manag 53:574–585

Miller RF, Bates JD, Svecar TJ, et al (2005) Biology, ecology, and management of western juniper (Juniperus occidentalis). Oregon State University Agricultural Experiment Station Technical Bulletin 152

Nelle PJ, Reese KP, Connelly JW (2000) Long-term effects of fire on sage grouse habitat. J Range Manag 53:586–591

Noson AC, Schmitz RA, Miller RF (2006) Influence of fire and juniper encroachment on birds in high-elevation sagebrush steppe. West North Am Nat 66:343–353

NRCS (2012a) Sage-Grouse Initiative Progress Report, FY 2012. Natural Resources Conservation Service. http://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/detailfull/plantmaterials/about/projects/?cid=steldevb1027671

NRCS (2012b) Sage-Grouse Initiative Status Report, FY 2010-2011. USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service. http://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/detailfull/plantmaterials/about/projects/?cid=steldevb1027671

NRCS (2012c) Soil Survey Staff, Natural Resources Conservation Service, United States Department of Agriculture. Web Soil Survey. http://websoilsurvey.nrcs.usda.gov

Polasky S, Nelson E, Camm J, Csuti B, Fackler P, Lonsdorf E, Montgomery C, White D, Arthur J, Garber-Yonts B (2008) Where to put things? Spatial land management to sustain biodiversity and economic returns. Biol Conserv 141:1505–1524

Possingham HP, Ball I, Andelman S (2000) Mathematical methods for identifying representative reserve networks. In: Ferson S (ed) Quantitative Methods in Conservation Biology, 1st edn. Springer-Verlag, New York, pp 291–305

PRISM Climate Group. (2012). Oregon State University. http://prism.oregonstate.edu

R Core Team (2014) R: A Language and Environmental for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna

Schmoldt DL (2001) The analytic hierarchy process in natural resource and environmental decision making. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Boston

Silverman BW (1986) Density estimation for statistics and data analysis. CRC Press, Florida

Soulé PT, Knapp PA, Grissino-Mayer HD (2004) Human agency, environmental drivers, and western juniper establishment during the Late Holocene. Ecol Appl 14:96–112

Twidwell D, Rogers WE, Fuhlendorf SD, Wonkka CL, Engle DM, Weir JR, Kreuter UP, Taylor CA (2013) The rising Great Plains fire campaign: citizens’ response to woody plant encroachment. Front Ecol Environ 11:e64–e71

USFWS (2010) Conference Report for the Natural Resources Conservation Service Sage Grouse Initiative (SGI). U.S Fish and Wildlife Service, Washington

Wang T, Hamann A, Spittlehouse DL, Murdock TQ (2011) ClimateWNA—high-resolution spatial climate data for Western North America. J Appl Meteorol Climatol 51:16–29

Williams JC, ReVelle CS, Levin SA (2005) Spatial attributes and reserve design models: a review. Environ Model Assess 10:163–181

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge T. Young and C. Hom for their invaluable guidance and support, B. Halstead, M. Brunson, and G. Patricelli for comments on previous versions of this manuscript, M. Ricca for sage-grouse model development, and C. Roeder, M. Merrill, and T. Esgate for assistance during field site visits. Authors SF, DY, AD, MH, EP, and GS were supported by the National Science Foundation Division of Graduate Education (DGE) #0801430, the Responding to Rapid Environmental Change (REACH) IGERT, awarded to UC Davis. The study described in this manuscript complies with the current laws of the United States of America.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Farzan, S., Young, D.J.N., Dedrick, A.G. et al. Western Juniper Management: Assessing Strategies for Improving Greater Sage-grouse Habitat and Rangeland Productivity. Environmental Management 56, 675–683 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-015-0521-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-015-0521-1