Abstract

Purpose

Trials of the direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) dabigatran, rivaroxaban and apixaban provide the basis for prescribing for the prevention of stroke and systemic embolism in atrial fibrillation (AF). The objective of this study was to assess the representativeness of the three pivotal DOAC randomized controlled trials of dabigatran, rivaroxaban and apixaban for unselected hospitalized patients with AF.

Methods

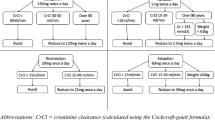

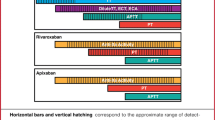

A cross-sectional study was undertaken. All patients discharged with AF between 2012 and 2015 from a large public hospital network in Melbourne, Australia, were identified. Inclusion and exclusion criteria from the DOAC trials were applied. The proportions of hospitalized patients with AF who would have been eligible for the dabigatran (RE-LY), rivaroxaban (ROCKET-AF) and apixaban (ARISTOTLE) trials were estimated, as was pooled eligibility for all three trials. Characteristics of eligible and ineligible patients were compared.

Results

For the 4734 patients, application of the inclusion and exclusion criteria resulted in 60.5, 52.6 and 35.8% eligibility for the trials of apixaban, dabigatran and rivaroxaban, respectively. Pooled eligibility across all three trials demonstrated that 33.4% of the patients would have been eligible for all three trials but 36.7% ineligible for any trial. Ineligible patients who met exclusion criteria were older and experienced more comorbidities.

Conclusions

The apixaban and dabigatran trials may be the most representative of hospitalized patients with AF. The DOAC trial results can readily be extrapolated to, and guide prescribing for, at least two thirds of patients discharged from a large metropolitan health service in Australia.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Connolly SJ et al (2009) Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 361(12):1139–1151

Patel MR et al (2011) Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 365(10):883–891

Granger CB et al (2011) Apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 365(11):981–992

Lee LH (2016) DOACs—advances and limitations in real world. Thromb J 14(1):17

Hylek EM, Ko D, Cove CL (2014) Gaps in translation from trials to practice: non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants (NOACs) for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation. Thromb Haemost 111(5):783–788

Tummala R et al (2016) Specific antidotes against direct oral anticoagulants: a comprehensive review of clinical trials data. Int J Cardiol 214:292–298

Ruff CT et al (2014) Comparison of the efficacy and safety of new oral anticoagulants with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet 383(9921):955–962

Potpara TS, Lip GH (2017) Postapproval observational studies of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation. JAMA 317(11):1115–1116

Larsen TB et al (2016) Comparative effectiveness and safety of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants and warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: propensity weighted nationwide cohort study. BMJ 353

Graham DJ et al (2016) Stroke, bleeding, and mortality risks in elderly Medicare beneficiaries treated with dabigatran or rivaroxaban for nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. JAMA Intern Med 176(11):1662–1671

Carmo J et al (2016) Dabigatran in real-world atrial fibrillation. Meta-analysis of observational comparison studies with vitamin K antagonists. Thromb Haemost 116(4):754–763

Yao X et al (2016) Effectiveness and safety of dabigatran, rivaroxaban, and apixaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. J Am Heart Assoc 5(6)

Lip GY et al (2012) Indirect comparisons of new oral anticoagulant drugs for efficacy and safety when used for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol 60(8):738–746

Schneeweiss S et al (2012) Comparative efficacy and safety of new oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 5(4):480–486

Van Spall HC et al (2007) Eligibility criteria of randomized controlled trials published in high-impact general medical journals: a systematic sampling review. JAMA 297(11):1233–1240

Glasser SP, Salas M, Delzell E (2007) Importance and challenges of studying marketed drugs: what is a phase IV study? Common clinical research designs, registries, and self-reporting systems. J Clin Pharmacol 47(9):1074–1086

Lee S et al (2012) Representativeness of the dabigatran, apixaban and rivaroxaban clinical trial populations to real-world atrial fibrillation patients in the United Kingdom: a cross-sectional analysis using the General Practice Research Database. BMJ Open 2(6)

Desmaele S et al (2016) Clinical trials with direct oral anticoagulants for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: how representative are they for real life patients? Eur J Clin Pharmacol 72(9):1125–1134

International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems, 10th Revision, Australian Modification (ICD-10-AM). Australian Consortium for Classification Development, Independent Hospital Pricing Authority: Darlinghurst, New South Wales

World Health Organisation Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology: Norwegian Institute of Public Health. Anatomical therapeutic chemical (ATC) classification system. 2015 [cited 2016 1 October]; Available from: http://www.whocc.no/atc_ddd_index/

Lip GY et al (2015) Oral anticoagulation, aspirin, or no therapy in patients with nonvalvular AF with 0 or 1 stroke risk factor based on the CHA2DS2-VASc score. J Am Coll Cardiol 65(14):1385–1394

SAS software, version 9.4. SAS Institute INC: Cary, USA

Vitale C, Rosano G, Fini M (2016) Are elderly and women under-represented in cardiovascular clinical trials? Implication for treatment. Wien Klin Wochenschr

Gage BF et al (2001) Validation of clinical classification schemes for predicting stroke: results from the National Registry of Atrial Fibrillation. JAMA 285(22):2864–2870

Flynn J, Lilly A (2015) Eastern Health Annual Report 2014–2015. Melbourne

Jaspers Focks J et al (2016) Polypharmacy and effects of apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: post hoc analysis of the ARISTOTLE trial. BMJ 353

Lip GY et al (2016) Real-world comparison of major bleeding risk among non-valvular atrial fibrillation patients initiated on apixaban, dabigatran, rivaroxaban, or warfarin. A propensity score matched analysis. Thromb Haemost 116(5):975–986

Staerk L et al (2015) Stroke and recurrent haemorrhage associated with antithrombotic treatment after gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation: nationwide cohort study. BMJ 351

Gorst-Rasmussen A, Lip GY, Bjerregaard Larsen T (2016) Rivaroxaban versus warfarin and dabigatran in atrial fibrillation: comparative effectiveness and safety in Danish routine care. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 25(11):1236–1244

Hilmer SN, Gnjidic D, Abernethy DR (2012) Pharmacoepidemiology in the postmarketing assessment of the safety and efficacy of drugs in older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 67(2):181–188

Freedman B, Lip GYH (2016) “Unreal world” or “real world” data in oral anticoagulant treatment of atrial fibrillation. Thromb Haemost 116(4):587–589

Yao X et al (2016) Effect of adherence to oral anticoagulants on risk of stroke and major bleeding among patients with atrial fibrillation. J Am Heart Assoc 5(2)

Raparelli V et al (2017) Adherence to oral anticoagulant therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation. Focus on non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants. Thromb Haemost 117(2):209–218

Steinberg BA et al (2015) Contraindications to anticoagulation therapy and eligibility for novel anticoagulants in older patients with atrial fibrillation. Cardiovasc Ther 33(4):177–183

Henderson T, Shepheard J, Sundararajan V (2006) Quality of diagnosis and procedure coding in ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care 44(11):1011–1019

The Independent Hospital Pricing Authority. Australian Refined Diagnosis Related Group (AR-DRG) classification system,. [cited 2016 18 October]; Available from: https://www.ihpa.gov.au/what-we-do/ar-drg-classification-system

Gattellari M et al (2011) Outcomes for patients with ischaemic stroke and atrial fibrillation: the PRISM study (A Program of Research Informing Stroke Management). Cerebrovasc Dis 32(4):370–382

Sluggett JK et al (2013) Transient ischaemic attack and ischaemic stroke: constructing episodes of care using hospital claims data. BMC Res Notes 6:128–128

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant from the Victorian Department of Health and Human Services, Clinical Leadership Group for the Care of Older People in Hospital and a Joint Medicine-Pharmacy Monash Strategic Grant. LF is supported by a Research Training Scheme PhD Scholarship from the Australian Government: Department of Education and Training. JI is supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council’s Early Career Fellowship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the concept and design. LF performed data analysis. LF performed drafting of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the data, manuscript revisions and read and approved the final manuscript. LF takes responsibility for the integrity of the data analysis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Approval for the study was obtained from both hospital and university Human Research Ethics Committees (ethics approval numbers LR2015-64 and CF16/1211).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fanning, L., Ilomäki, J., Bell, J.S. et al. The representativeness of direct oral anticoagulant clinical trials to hospitalized patients with atrial fibrillation. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 73, 1427–1436 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-017-2297-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-017-2297-0