Abstract

Kelp forests are extensive, widely distributed and highly productive. However, despite their importance, reliable estimates of net primary productivity (NPP) are currently unknown for most species and regions. In particular, how performance and subsequent NPP change throughout a species range is lacking. Here, we attempted to resolve this by examining growth and performance of the boreal kelp, Laminaria digitata, from range centre and trailing edge regions in the United Kingdom. During the peak growth season (March/April), range-centre individuals were up to three times heavier and accumulated biomass twice as fast as their trailing-edge counterparts. This was not apparent during the reduced growth season (August/September), when populations within both regions had similar biomass profiles. In total, annual NPP estimates were considerably lower for trailing-edge (181 ± 34 g C m−2 year−1) compared to range-centre (344 ± 33 g C m−2 year−1) populations. Our first-order UK estimates of total standing stock and NPP for L. digitata suggest this species makes a significant contribution to coastal carbon cycling. Further work determining the ultimate fate of this organic matter is needed to understand the overall contribution of kelp populations to regional and global carbon cycles. Nevertheless, we highlight the need for large-scale sampling across multiple populations and latitudes to accurately evaluate kelp species’ contributions to coastal carbon cycling.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Macroalgae (i.e. kelps and other seaweeds) underpin some of the most extensive and productive coastal ecosystems globally (Mann 1973; Smith 1981; Duarte and Cebrián 1996). Many macroalgal species, including most kelps, exhibit high rates of productivity and rapid biomass turnover, with growth values of up to 2–4% of standing biomass per day (Reed et al. 2008). However, unlike other coastal macrophytes (e.g. seagrasses, mangroves and other halophytes), macroalgae grow attached to hard substrata (rather than within sediments) and as such do not allocate biomass to ‘below ground’ storage (Duarte 2017). Consequently, the vast majority of biomass accumulation (generally > 80% of production) is released as particulate organic matter, or detritus, which represents an important trophic resource for bacteria, suspension feeders and detritivores, and enhances trophic connectivity in coastal marine ecosystems (Kaehler et al. 2006; Krumhansl and Scheibling 2012). Moreover, emerging evidence suggests a significant proportion of macroalgal detritus may be sequestered in carbon sinks (up to 25%, see Krause-Jensen and Duarte 2016), such as coastal sediments and the deep sea (Chung et al. 2011; Hill et al. 2015; Krause-Jensen and Duarte 2016; Filbee-Dexter et al. 2018; Krause-Jensen et al. 2018; Ortega et al. 2019; Queirós et al. 2019). In light of this, it has been argued that macroalgae should be incorporated into blue carbon assessments (Duarte et al. 2013; Hill et al. 2015; Sondak and Chung 2015; Trevathan-Tackett et al. 2015; Smale et al. 2018; Macreadie et al. 2019). Despite the fundamental role that macroalgae, and kelp species in particular, play in coastal carbon cycling, reliable estimates of carbon fixation (i.e. productivity) are currently lacking for most species and regions (Reed and Brzezinski 2009).

Understanding the role that kelp species play within local and global carbon (C) cycles requires quantification of primary production rates under different environmental conditions and throughout a given species’ range, to elucidate regional differences in demographic performance. The “Abundant-Centre Hypothesis” (ACH) (also known as “centre-periphery” or “central-marginal” hypotheses) is a common paradigm in biogeography. The ACH assumes conditions are optimal at the range centre and become increasingly less favourable toward the periphery (Hengeveld and Haeck 1982; Brown 1984), which results in a reduction in genetic diversity, performance and abundance at range margins. However, meta-analyses have revealed that there is often little empirical support for the ACH challenging its generality across species (Sagarin and Gaines 2002; Dallas et al. 2017; Pironon et al. 2017) and to what extent kelp species conform to the ACH is largely unknown. On the one hand, the high degree of local adaptation observed for some marine macrophytes may maintain performance throughout a species range (see King et al. 2018a, b). On the other, stressful abiotic (e.g. temperature) and ecological (e.g. inter-specific competition) conditions and subsequent reduced genetic diversity may impair performance (Eckert et al. 2008; Viejo et al. 2011; Smale and Wernberg 2013; Straub et al. 2019; Wernberg et al. 2018).

The latitudinal distributions of kelp species are strongly constrained by temperature (Eggert 2012) and, as such, they are influenced by contemporary and near-future ocean warming trends (reviewed by Smale 2020). Assuming no local adaptation or plasticity, climate-driven poleward range shifts may result in considerable losses of standing biomass and reduced rates of primary productivity from any given species’ trailing edge (Wernberg et al. 2016; Arafeh-Dalmau et al. 2019). Moreover, rising temperatures will likely impact performance throughout the entire species range, with current ‘cold’ populations likely to function similarly to current ‘warm’ populations over the coming decades (Pessarrodona et al. 2018). As such, determining how kelp performance varies between populations and across latitudes is a prerequisite to understanding how the capture and flow of carbon through temperate reef ecosystems systems may change in the future.

Rocky coastlines in the northeast (NE) Atlantic region are dominated by kelp forests, which are thought to make a substantial contribution to coastal primary production (Jupp and Drew 1974; Kain 1979; Pessarrodona et al. 2018; Pedersen et al. 2020). However, the current state of knowledge on the dynamics of NE Atlantic kelp forests is limited, as they have been chronically understudied compared to some other temperate regions (Smale et al. 2013). Laminaria digitata (Hudson) J.V. Lamouroux is a cool boreal kelp with a transatlantic distribution. In the NE Atlantic, it is distributed from the Arctic to the English Channel and is predicted to undergo a poleward range contraction over the coming decades (Raybaud et al. 2013; Assis et al. 2018). Here, we compared the performance of L. digitata in two thermally distinct regions in the United Kingdom (UK) representing trailing edge and range centre populations, during periods of maximum and minimum productivity. Our overall aim was to quantify primary productivity rates for L. digitata in the UK and to explore more generally to what degree this species conforms to the ACH.

Methods

Survey design

Here, we aimed to characterise how L. digitata’s performance changes between sites at its range centre (RC) and trailing edge (TE). Sampling across large geographical scales and attributing differences to particular variables is challenging as many local factors can affect performance and obscure regional patterns. To address this, we picked sites that were similar in local environmental factors so that we could attribute changes to either temperature or light that co-vary with latitude.

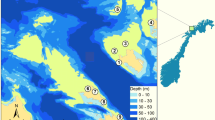

Following a nested design, we chose three sites at L. digitata’s range centre and three at its trailing edge (Fig. 1). Based on neutral markers and common garden temperature stress assays, King et al. (2019) showed there is little gene flow between these regions and trailing edge populations may represent distinct thermal ecotypes. Mean annual sea surface temperatures within the RC region are ~ 2.3 °C lower than those within the TE region. These regional temperature differences become more apparent in summer where differences between regions are ~ 3.3 °C (Table 1). To minimise local effects of wave exposure on kelp performance and morphology (Gerard and Mann 1979; Blanchette et al. 2002; Fowler-Walker et al. 2006; Millar et al. 2019) only fully exposed shores were selected. Wave exposure was measured using log wave fetch derived from summing fetch values calculated for 32 angular sectors surrounding each study site (see Burrows 2012). Flow rates were greater at trailing edge sites but all still represented low flow sites for L. digitata (< 0.4 m s−1; see Millar et al. 2019). Nutrients were not directly measured but UK coastlines are not characterised by major upwelling regimes and nutrients do not vary greatly with latitude (Painting et al. 2013). Moreover, previous studies have shown no significant difference in nutrient concentrations between our study regions (Smale et al., 2016; Pessarrodona et al. 2018).

Growth rates of L. digitata exhibit pronounced seasonality, with a period of rapid biomass accumulation occurring from February to June, followed by a period of reduced growth from August to January. This pattern coincides with regeneration of nutrients in spring and their depletion in summer and is triggered by changes in photoperiod (Kain and Jones 1969; Davison and Stewart 1984) and onset of fertility (Buchholz and Lüning 1999). During summer, photosynthetic products are stored as carbohydrates, which are later remobilised as new growth is initiated in the spring (Schaffelke and Lüning 1994). Therefore, surveys were conducted during peak growth, March–April (2015), and reduced growth, August–September (2015), periods to encompass the different phases of biomass accumulation in L. digitata (Table S9).

Measuring individual performance

Population demographics: Kelp density was quantified at each site by haphazardly placing eight 1 m2 quadrats within the kelp forest and recording the number of mature individuals (defined as dominate space occupiers with a stipe length > 30 cm). Sampling was conducted in the middle of the L. digitata zone (~ 0.5-0.8 m above chart datum) during periods of low tide emersion. Due to logistical challenges, it was only possible to obtain density data during sampling in the peak growth season. However, L. digitata is a perennial species, persisting for up to ~ 6 years, and seasonal surveys conducted on other UK populations have shown that densities are relatively stable throughout the year (Hereward et al. 2018). Morphological and biomass estimates were taken for ~ 20 individuals at each site. Note: these are the same individuals used for growth estimates (see below). The age of individual plants was not determined.

Blade elongation and biomass accumulation: Like most Laminariales, L. digitata exhibits a ‘conveyor belt’ growth strategy, with new tissue formed by the meristematic area at the base of the blade and older material translocating towards the distal tips of the blade. Therefore, elongation rate, estimated by punching of a hole and measuring its distance travelled, has been used as a reliable measure of relative growth rates (Parke 1948). An adaptation of this method allows the quantification of the actual biomass laid down by taking into account morphology (Mann and Kirkman 1981; Krumhansl and Scheibling 2011). At each sampling period, 20 individuals were randomly selected from within the L. digitata stand. Two holes were punched into the central digit of the blade of each individual, at 5 and 10 cm from the junction between the stipe and the meristem. After 4–6 weeks, individuals were relocated and returned to the laboratory for analysis. Lamina extension was calculated as the sum of the distance between each hole and the stipe/meristem junction at the end of the growth period, minus the initial distance of the holes from the base of the blade.

To convert elongation rates (cm) to daily biomass accumulation (g), three 5 cm wide (running perpendicular to the kelp blade) basal segments were cut from above the meristem (Fig. S1).

The relationship between weight and position along the blade is constant around a maximum value past an initial area of regrowth where weight increases with distance from the meristem. To ensure we did not underestimate performance we used the heaviest segment (basal segment 3 in all cases) to calculate individual daily biomass accumulation (g FW day−1) using Eq. (1):

where e is lamina extension (cm), W is fresh weight of the heaviest basal segment (divided by 5 to give g cm−1 of lamina) and t is the number of days between initial hole-punching and kelp collection.

Converting to site level productivity

To attain site level estimates of primary productivity from individual biomass accumulation rates we used conversion factors to firstly convert FW to dry weight (DW) and then to carbon (C) biomass. FW:DW was not measured at our study sites and so conversions were obtained from monthly sampling of independent populations of L. digitata from two sites in Plymouth Sound, SW England (West Hoe, 50.363045, − 4.139226; Mount Batten, 50.356469, − 4.127217) (Table S9). Monthly FW:DW relationships were determined by drying the heaviest basal segment for biomass accumulation at 60 °C for 48 h. For tissue carbon, 5 basal segments were randomly selected from individuals used for growth estimates. These were frozen (− 20 °C), subsequently dried and then ground to a fine powder and C content quantified with a standard elemental analyser (CHN Analyser, EA1110, EE Instruments Ltd, Wigan).

Site level standing stock of carbon (g C m−2) was quantified using Eq. (2):

where SS is the standing stock, w is the mean individual plant weight (g FW), d is the mean population density (m2) of canopy forming individuals (stipe length > 30 cm), x is the FW:DW conversion factor (based on reference sites in Plymouth Sound) and c is the C content conversion factor (site level estimate).

For each sampling period, we then calculated site level net daily primary productivity (g C m−2 day−1) using Eq. (3):

where sNPP is the site Net Primary Productivity, B is the mean daily biomass accumulation, d is the mean population density, x is the FW:DW conversion factor (based on reference sites in Plymouth Sound) and c is the C content conversion factor (site level estimate).

To extrapolate from our two sampling periods to annual rates of productivity we needed to determine the relative contributions of our observation periods to the total annual growth cycle. L. digitata’s annual growth cycle was characterised at the two reference sites in Plymouth Sound and assumed to represent L. digitata’s growth cycle throughout our study area. At the two reference sites, productivity was measured monthly (using the same technique described above) and each month’s contribution to total productivity calculated (Table S9). The percentage contribution of April (Peak) and August (Reduced) to annual productivity (g C m−2 year−1) was used to determine annual using Eq. (4):

where aNPP is the annual net primary productivity, B is the mean daily biomass accumulation, M is the standard month (30.5 days) and P is the percentage contribution of sampling month to overall annual productivity (determined from reference sites in Plymouth Sound; Table S9). aNNP was calculated independently using measurements from both the peak (April) and the reduced (August) growth periods and annual estimates are a mean of the two values (Table S11). Finally, we generated first-order estimates of the total areal standing stock of C and NPP for L. digitata stands in the UK. The spatial extent of suitable habitat was determined by summing the length of coastline in the UK dominated by rock or cobble habitat that is semi-to-fully exposed to wave action (Burrows et al. 2008), which represents favourable conditions for L. digitata (Burrows 2012). Based on surveys and observations, L. digitata was assumed to inhabit a ~ 20 m wide band along the low intertidal/subtidal fringe (depth range ~ 0–0.7 m above chart datum) of this section of coastline. To gain UK wide estimates of aNPP and total areal standing stock, L. digitata’s spatial extent (km2) was multiplied by the study wide mean estimates of site level standing stock (g C m−2) and aNPP (g C m−2 year−1).

Statistical analysis

Variability in individual kelp (length, blade weight, elongation, weight of heaviest basal segment, biomass accumulation and tissue carbon) and site level (abundance, standing stock) metrics were determined using univariate Permutational Analysis of Variance (PERMANOVA), using the PERMANOVA module (Anderson 2001) within Primer 6 software (Clarke and Gorley 2001). A similarity matrix was generated for each metric based on Euclidean distance and variability tested with 9999 permutations untransformed data under a reduced model.

For length, weight, elongation, weight of heaviest basal segment, biomass accumulation and tissue carbon, model factors consisted of Region (fixed factor; 2 levels: Range Centre, Trailing Edge), Site (random factor, 3 levels nested within Region) and Season (fixed factor; 2 levels: Peak and Reduced). For density, the model consisted of Region (fixed factor; 2 levels: Range Centre, Trailing Edge) and Site nested within region. For standing stock, replication was at the site level so the model consisted of Region (fixed factor; 2 levels: Range Centre, Trailing Edge) and Season (fixed factor, 2 levels: Peak, Reduced). Differences in mean annual estimates of primary productivity between regions was determined using a t test. All values are presented as means + standard error (SE).

Results

The mean density of canopy forming individuals per site ranged from 6.5 (± 1.5 SE) ind. m−2 to 9.4 (± 3.5 SE) ind. m−2 and did not differ between sites (nested within regions) or between regions (Table S1; Fig. 2). All individual metrics (i.e. length, fresh weight biomass, elongation, weight of heaviest basal segment and biomass accumulation) exhibited significant Season × Site(Region) interactions. This means there was significant variability between sites from the same region but only in one season. In all cases, this was driven by greater variability in the peak growth season. For example, in the range centre region, average blade length between sites varied from 142.4 (± 10.4 SE) cm (RC3) to 223.5 ± 13.5 cm (RC2) (range 81.1 cm), whereas in the reduced growth season length varied from 96.4 (± 3.97 SE) cm (RC3) compared to 111.8 ± (6.95 SE) cm (RC1) (range 15.4 cm). Similarly, fresh weight biomass varied from 573.2 (± 44.8 SE) g (RC2) to 999.5 ± (106.5 SE) g (RC3) (range 426 g), whereas in the reduced season weight profiles varied from 267.1 ± (62.6 SE) g (RC2) to 398.3 (± 61.1 SE) g (RC3) (range 131.2).

Overall, for blade length, we found no effect of region but lengths differed between seasons. In the peak growth season, blade length was 166.2 ± (4.8 SE) cm compared to 107.9 (± 2.8 SE) cm in the reduced growth season (Table S2). For fresh weight biomass, we detected an interaction between Region and Season (Table S3). Whilst there was considerable within region variability in the peak growth season, all values at range centre sites were greater than trailing edge sites, indicating clear directional generality. In the peak growth season, individual fresh weight biomass in the range centre region was 810.9 (± 58.8 SE) g compared to 235.5 (± 10.9 SE) g in the trailing edge region. These regional differences were not apparent during the reduced growth season where individual fresh weight biomass was similar between regions at 336.6 (± 33.3 SE) g in the range centre region and 251.5 (± 18.9 SE) g in the trailing edge region. Daily elongation rates varied markedly between sites but were comparable across regions, and exhibited pronounced seasonal variability (Table S4; Fig. 3c). During the peak growth season, mean daily blade elongation was 0.71 (± 0.08 SE) cm but fell to 0.13 (± 0.02 SE) cm during the reduced growth period. The weight of the heaviest basal segment also varied considerably between sites (Fig. 3d). In particular, RC3 was over twice as heavy as other sites within the same region, during the peak growth season. The weight of the heaviest basal segment differed between regions but there was no main effect of season (Table S5). The weight of the heaviest basal segment was 23.9 (± 1.8 SE) g FW in the range centre region compared to 12.1 (± 0.3 SE) g FW in the trailing edge region.

Mean (+ SE) population demographics of canopy forming Laminaria digitata (stipe length > 30 cm) across study sites and growth season. a Total blade length, b Total blade weight, c Blade elongation rate and d Weight of heaviest basal segment. While 20 individuals were tagged, the number of individuals harvested for sampling varied between 9 and 17 (Table S10)

For fresh weight biomass accumulation, we detected an interaction between Region and Season. Whilst there was considerable within region variability, there was clear directional generality with range centre sites larger than trailing edge sites (Table S6; Fig. 4a). During the peak growth season, mean biomass accumulation was 3.6 (± 0.2 SE) g FW day−1 in the range centre region compared to 1.7 (± 0.1 SE) g FW day−1 in the trailing edge region (Fig. 4b). In the reduced growth season, biomass accumulation was similar between regions at 0.45 (± 0.04 SE) g FW day−1 in the range centre and 0.28 (± 0.01 SE) g FW day−1 in the trailing edge (Fig. 4b).

Site (a + c) and region (b + d) level estimates of biomass accumulation (a + b) and carbon standing stock (c + d) for L. digitata in its peak (non-hatched bars) and reduced (hatched bars) growth season. c Represents individual site values from Eq. (2) and as such has no error. All other values are mean ± SE

For % tissue carbon, we found no effect of region but there was a seasonal effect. In the peak growth season, tissue carbon was 30.2 (± 0.19 SE) % compared to 33.7 (± 0.31 SE) % in the reduced growth season (Table S6). Standing stock of C exhibited a significant Region × Season interaction (Table S8; Fig. 4c and d). In the peak growth season, C standing stock in the range centre region was 278 (± 59 SE) g C m−2 compared to 79 (± 11 SE) g C m−2 in the trailing edge region. During the reduced growth season, average C stocks were similar between regions at 166.9 (± 4.6 SE) g C m−2 in the range centre region and 113.1 (± 29.4 SE) g C m−2 at the trailing edge (Fig. 4d).

Our site-level estimates of annual NPP varied markedly between sites, ranging from 135 to 402 g C m−2 year−1 (Fig. 5a). Overall, annual NPP rates were significantly greater in the range centre region, at 344 (± 33 SE) g C m−2 year−1 compared to the trailing edge region, at 181 (± 34 SE) g C m−2 year−1 (t = 2.65, p = 0.05) (Fig. 5b). We calculated that across the UK, approximately 4270 km of coastline met the criteria of being both dominated by hard substrata and semi-to-fully exposed to wave action. Based on L. digitata existing within a 20 m vertical band along these shorelines, this translates to an estimated areal extent of 85 km2.

Site (a) and region (b) level estimates of annual net primary productivity for L. digitata. a Represents individual site values from Eq. (4), and as such, has no error. b Represents mean ± SE

Based on study-wide mean values for standing stock and annual NPP of 159 g C m−2 and 262 g C m−2 year−1, respectively, we estimate that L. digitata populations in the UK hold at least 13,515 t C and turnover 22,270 t C each year.

Discussion

Understanding the role that macroalgae play in carbon cycling has gained increased attention in recent years, yet robust estimates of primary productivity and carbon fluxes in marine environments have been hindered by a lack of reliable data, particularly across large spatial scales. For L. digitata, our study wide estimates of standing stock ranged from 62 to 397 g C m−2 with a mean of 159 g C m−2, which is comparable to estimates for L. digitata in both France (162 g C m−2, Gevaert et al. 2008) and Nova Scotia (120 to 420 g C m−2, Krumhansl and Scheibling 2011). However, this is considerably lower than standing stock estimates for many other kelp populations, including the subtidal congeneric species, Laminaria hyperborea, in the NE Atlantic (e.g. 721 g C m−2, Smale et al. 2016; 770 g C m−2, Pedersen et al. 2020). This is likely driven by differences in stipe morphology with L. hyperborea possessing a much larger, heavier and more rigid stipe compared to L. digitata. Annual estimates of NPP ranged from 135 to 402 g C m−2 year−1, with a mean of 262 g C m−2 year−1, which is again markedly lower than estimates for L. hyperborea in the NE Atlantic (Kain, 1971; Sheppard et al. 1978; Pedersen et al. 2020) and for many other macroalgal stands globally (Krause-Jensen and Duarte, 2016). In temperate regions of the NE Atlantic, L. digitata is restricted to a narrow band within low intertidal/shallow subtidal habitats, as it is competitively inferior to L. hyperborea in most subtidal environments (Hawkins and Harkin, 1985). Even so, L. digitata is widespread and often abundant on rocky shores in the British Isles (Yesson et al. 2015) and along the wider northwest European coastline (Raybaud et al. 2013), it can penetrate into deeper waters in polar regions (Hop et al. 2012) and is likely to be an important contributor to benthic primary production.

Whilst the abundance of L. digitata was fairly consistent across our study sites, ecological performance (in terms of growth and productivity) varied between our northern range centre and southern trailing edge populations. During the peak growth season, biomass accumulation was lower at trailing edge sites and individuals had up to three times less biomass, suggesting conditions in this region are less favourable for growth. Laboratory experiments have shown L. digitata can grow over a broad range of temperatures with optimum growth occurring between 10 and 15 °C (Bolton and Lüning 1982; tom Dieck 1992). Temperatures experienced in both regions during the springtime period of peak-growth fall within this optimal temperature range, whereas during the summertime period of reduced-growth both water and air temperatures experienced at trailing edge sites can induce considerable stress (Hargrave et al. 2017; Hereward et al. 2020). The trailing edge region also receives more sunshine hours than the range centre, and as such, likely receives higher amounts of harmful UV radiation, causing additional stress (Bischof et al. 2006). This means resources at the trailing edge may be allocated towards maintenance and repair at the cost of growth. On top of this stress gradient, mean summer day lengths are approximately 2 h longer at the range centre. This is important as long days in summer are used to store sugars to be mobilised the following spring when new growth is initiated (see Rinde and Sjøtun, 2005 and references therein). It seems despite evidence for local adaptation to greater temperature stress for L. digitata’s trailing edge populations (King et al. 2019), performance is aligned with the Abundant Centre Hypothesis, likely through a combination of stressful temperatures and less time for photosynthesis in summer. However, as growth patterns in L. digitata are entrained by photoperiod (Gomez and Lüning 2001) and photoperiod differs between range centre and trailing edge regions, our observed regional differences in productivity may also, in part, be due to regional differences in L. digitata’s circannual rhythmicity. Future studies fully characterizing annual growth patterns between regions coupled with in situ measures of stress will be able to fully resolve this. It is important to note that regional differences in performance were not related to rates of elongation or total blade length but rather transient morphologies observed during the peak growth season. In general, total blade biomass and maximum weight of basal segments was greater at range centre compared with trailing edge sites, particularly during the peak growth season. Whilst elevated flow rates can increase productivity and overall biomass in L. digitata (e.g. Millar et al. 2019), it is unlikely flow is responsible for our observed differences in regional performance as patterns run counter to our results i.e. despite lower flow rates, range centre individuals are larger and more productive. Moreover, the transient nature of our suggested morphological differences between regions is not conducive to persistent regional differences in hydrodynamic regime. As growth can occur laterally in Laminaria spp (e.g. Calvin and Ellis 1981), regional differences in performance in the peak growth season may be driven by regional differences in lateral growth and subsequent width at this time. We did not explicitly measure width, and examples of temperature mediated lateral growth are lacking in L. digitata. However, elevated lateral growth has been observed at cooler parts of a kelps range (Mabin et al. 2013), at cooler depths (Boden 1979) and in cooler common garden mesocosm treatments (Okada et al. 1985 as cited in Bartsch et al. 2008) and, based on our qualitative observations, may explain some of the regional variability reported here. Differences in maximum weight of basal segments were likely related to blade width, thickness and mass by unit area. Northern range centre populations may have also formed thicker blades, with greater concentration of storage compounds, pigments and other products, under more favourable conditions.

Our results have clear implications for understanding coastal carbon cycling in the face of climate change, particularly ocean warming. So far, the majority of climate change research on kelp species has focussed on either predicting (e.g. Müller et al. 2009; Raybaud et al. 2013; Franco et al. 2018; Assis et al. 2018; Khan et al. 2018) or documenting species’ range shifts (Wernberg et al. 2011; Smale et al. 2015), including population losses at trailing edges (e.g. Wernberg et al. 2016; Arafeh-Dalmau et al. 2019). In contrast, far less is known about how ocean warming may alter ecological performance and carbon dynamics within any given species range (but see Pessarrodona et al. 2018). We documented marked variability in primary productivity rates across a ~ 2.5 °C average sea temperature gradient. Similar trends have been observed for kelp population structure (Smale et al. 2016), kelp forest composition (Smale and Moore 2017), detrital production rates (Pessarrodona et al. 2018) and primary productivity (Smale et al. in review) in subtidal habitats along the same temperature gradient. Given this temperature gradient is comparable to the magnitude of ocean warming predicted for the NE Atlantic by 2100 (Philippart et al. 2011), tentative predictions of changes in the coming decades can be drawn. While future temperatures may remain within L. digitata’s growth optimum in the peak growth season, increased stress during summer may reduce overall productivity to levels currently seen at trailing edge sites. Moreover, should L. digitata undergo a range contraction at the trailing edge, as has been predicted (Raybaud et al. 2013), both standing stock and benthic NPP would decline dramatically within our warmer trailing edge region. Ocean warming has had, and will continue to have, major impacts on kelp populations and the ecosystems they underpin in many regions around the world (Smale et al. 2020). Our results suggest that their role within coastal carbon cycles will also be affected in coming decades.

In conclusion, we quantified standing stock and NPP of L. digitata stands at its range centre and trailing edge sites in the UK, and identified clear differences in demography and ecological performance between thermally distinct regions. Understanding variability in primary productivity between populations and regions is necessary to better predict current and future responses to environmental change, particularly ocean warming. More generally, our estimate of spatial extent suggests that L. digitata stands occupy ~ 85 km2 (i.e. 8500 ha) of coastal habitat, which is ~ 6 times that of maerl beds (Burrows et al. 2014), ~ 1 times that of seagrass meadows (Green et al. 2018) and ~ 1/5 that of salt marsh (Beaumont et al. 2014) coverage in the UK. Given that these stands store and release significant amounts of particulate C (i.e. 13,515 t C and 22,270 t C year−1 respectively), it is important to advance understanding of the pathways and ultimate fate of this material, to fully appreciate the role these habitats play in C cycling and as potential blue carbon donors. If even only a fraction of this material reaches and resides within carbon storage habitats, as has been suggested (Krause-Jensen and Duarte 2016; Pessarrodona et al. 2018; Ortega et al. 2019), then the process of C donation has elevated importance and the implications of climate change-carbon cycling feedbacks may be considerable.

Availability of data

Data available at https://figshare.com/s/8f0bd6355575f0f40091.

References

Anderson MJ (2001) A new method for non-parametric multivariate analysis of variance. Austral Ecol 26(1):32–46

Arafeh-Dalmau N, Montaño-Moctezuma G, Martinez JA, Beas-Luna R, Schoeman DS, Torres-Moye G (2019) Extreme marine heatwaves alter kelp forest community near its equatorward distribution limit. Front Mar Sci 6:499

Assis J, Araújo MB, Serrão EA (2018) Projected climate changes threaten ancient refugia of kelp forests in the North Atlantic. Global Change Biol 24(1):e55–e66

Bartsch I, Wiencke C, Bischof K, Buchholz CM, Buck BH, Eggert A, Feuerpfeil P, Hanelt D, Jacobsen S, Karez R (2008) The genus Laminaria sensu lato: recent insights and developments. Eur J Phycol 43(1):1–86

Beaumont NJ, Jones L, Garbutt A, Hansom J, Toberman M (2014) The value of carbon sequestration and storage in coastal habitats. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci 137:32–40

Bischof K, Gomez I, Molis M, Dieter H, Karsten U, Roleda MY, Zacher K, Wiencke C (2006) UV radiation shapes seaweed communities. Rev Environ Sci 5:141–166

Blanchette C, Miner B, Gaines S (2002) Geographic variability in form, size and survival of Egregia menziesii around point conception, California. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 239:69–82

Boden GT (1979) The effect of depth on summer growth of Laminaria saccharina (phaeophyta, laminariales). Phycologia 18(4):405–408

Bolton J, Lüning K (1982) Optimal growth and maximal survival temperatures of Atlantic Laminaria species (phaeophyta) in culture. Mar Biol 66(1):89–94

Brown JH (1984) On the relationship between abundance and distribution of species. Am Nat 124(2):255–279

Buchholz C, Lüning K (1999) Isolated, distal blade discs of the brown alga Laminaria digitata form sorus but not discs, near to the meristemic transition zone. J Appl Phycol 16:579–584

Burrows MT (2012) Influences of wave fetch, tidal flow and ocean colour on subtidal rocky communities. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 445:193–207

Burrows MT, Harvey R, Robb L (2008) Wave exposure indices from digital coastlines and the prediction of rocky shore community structure. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 353:1–12

Burrows MA, Kamenos NA, Hughes DJ, Stahl H, Howe JA, Tett P (2014) Assessment of carbon budgets and potential blue carbon stores in Scotland’s coastal and marine environment. Scottish Natural Heritage Commissioned Report No. 761

Calvin NI, Ellis R (1981) Growth of subtidal Laminaria groenlandica in southeastern Alaska related to season and depth. Bot Mar 24(2):107–114

Chung IK, Beardall J, Mehta S, Sahoo D, Stojkovic S (2011) Using marine macroalgae for carbon sequestration: a critical appraisal. J Appl Phycol 23(5):877–886

Clarke K, Gorley R (2001) 2006. PRIMER v6: user manual/tutorial. PRIMER-E, Plymouth

Dallas T, Decker RR, Hastings A (2017) Species are not most abundant in the centre of their geographic range or climatic niche. Ecol Lett 20(12):1526–1533

Davison I, Stewart W (1984) Studies on nitrate reductase activity in Laminaria digitata (huds.) lamour. I. longitudinal and transverse profiles of nitrate reductase activity within the thallus. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 74(2):201–210

Duarte CM (2017) Reviews and syntheses: hidden forests, the role of vegetated coastal habitats in the ocean carbon budget. Biogeosciences 14(2):301–310

Duarte CM, Cebrián J (1996) The fate of marine autotrophic production. Limnol Oceanogr 41(8):1758–1766

Duarte CM, Losada IJ, Hendriks IE, Mazarrasa I, Marbà N (2013) The role of coastal plant communities for climate change mitigation and adaptation. Nat Clim Change 3(11):961–968

Eckert C, Samis K, Lougheed S (2008) Genetic variation across species’ geographical ranges: the central–marginal hypothesis and beyond. Mol Ecol 17(5):1170–1188

Eggert A (2012) Seaweed responses to temperature. Seaweed biology. Springer, Berlin, p 47

Filbee-Dexter K, Wernberg T, Norderhaug KM, Ramirez-Llodra E, Pedersen MF (2018) Movement of pulsed resource subsidies from kelp forests to deep fjords. Oecologia 187(1):291–304

Fowler-Walker MJ, Wernberg T, Connell SD (2006) Differences in kelp morphology between wave sheltered and exposed localities: morphologically plastic or fixed traits? Mar Biol 148(4):755–767

Franco JN, Tuya F, Bertocci I, Rodríguez L, Martínez B, Sousa-Pinto I, Arenas F (2018) The” golden kelp’ Laminaria ochroleuca under global change: integrating multiple eco-physiological responses with species distribution models. J Ecol 106:47–58

Gerard VA, Mann KH (1979) Growth and production of Laminaria longicruris (phaeophyta) populations exposed to different intensities of water movement 1. J Phycol 15(1):33–41

Gevaert F, Janquin M, Davoult D (2008) Biometrics in Laminaria digitata: a useful tool to assess biomass, carbon and nitrogen contents. J Sea Res 60(3):215–219

Gomez I, Lüning K (2001) Constant short-day treatment of outdoor-cultivated Laminaria digitata. Eur J Phycol 36:391–395

Green A, Chadwick MA, Jones PJS (2018) Variability of UK seagrass sediment carbon: implications for blue carbon estimates and marine conservation management. PLoS ONE 13(9):e0204431

Hargrave MS, Foggo A, Pessarrodona A, Smale DA (2017) The effects of warming on the ecophysiology of two co-existing kelp species with contrasting distributions. Oecologia 183(2):531–543

Hawkins S, Harkin E (1985) Preliminary canopy removal experiments in algal dominated communities low on the shore and in the shallow subtidal on the Isle of Man. Bot Mar 28(6):223–230

Hengeveld R, Haeck J (1982) The distribution of abundance. I. Measurements. J Biogeogr 9:303–316

Hereward HF, Foggo A, Hinckley SL, Greenwood J, Smale DA (2018) Seasonal variability in the population structure of a habitat-forming kelp and a conspicuous gastropod grazer: do blue-rayed limpets (Patella pellucida) exert top-down pressure on Laminaria digitata populations? J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 506:171–181

Hereward HF, King NG, Smale DA (2020) Intra-annual variability in responses of a canopy forming kelp to cumulative low tide heat stress: implications for populations at the trailing range edge. J Phycol 56:146–158

Hill R, Bellgrove A, Macreadie PI, Petrou K, Beardall J, Steven A, Ralph PJ (2015) Can macroalgae contribute to blue carbon? An Australian perspective. Limnol Oceanogr 60(5):1689–1706

Hop H, Wiencke C, Vögele B, Kovaltchouk NA (2012) Species composition, zonation, and biomass of marine benthic macroalgae in Kongsfjorden, Svalbard. Bot Mar 55:399–414

Jupp BP, Drew EA (1974) Studies of the growth of Laminaria hyperborea (Gunn.) Fosl. I. Biomass and productivity. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 15:185–196

Kaehler S, Pakhomov E, Kalin R, Davis S (2006) Trophic importance of kelp-derived suspended particulate matter in a through-flow sub-Antarctic system. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 316:17–22

Kain JM (1971) Synopsis of biological data on Laminaria hyperborea. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

Kain JM (1979) A view of the genus Laminaria. Oceanogr Mar Biol 17:101–161

Kain JM, Jones MN (1969) The biology of Laminaria hyperborea. V. Comparison with early stages of competitors. J Mar Biol Assoc UK 49(2):455–473

Khan AH, Levac E, Van Guelphen L, Pohle G, Chmura GL (2018) The effect of global climate change on the future distribution of economically important macroalgae (seaweeds) in the Northwest Atlantic. Facets 3(1):275–286

King NG, McKeown NJ, Smale DA, Moore PJ (2018a) The importance of phenotypic plasticity and local adaptation in driving intraspecific variability in thermal niches of marine macrophytes. Ecography 41(9):1469–1484

King NG, Wilcockson DC, Webster R, Smale DA, Hoelters LS, Moore PJ (2018b) Cumulative stress restricts niche filling potential of habitat-forming kelps in a future climate. Funct Ecol 32(2):288–299

King NG, McKeown NJ, Smale DA, Wilcockson DC, Hoelters L, Groves EA, Stamp T, Moore PJ (2019) Evidence for different thermal ecotypes in range centre and trailing edge kelp populations. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 514:10–17

Krause-Jensen D, Duarte CM (2016) Substantial role of macroalgae in marine carbon sequestration. Nat Geosci 9(10):737–742

Krause-Jensen D, Lavery P, Serrano O, Marba N, Masque P, Duarte CM (2018) Sequestration of macroalgal carbon: the elephant in the blue carbon room. Biol Let 14(6):20180236

Krumhansl KA, Scheibling RE (2011) Detrital production in Nova Scotian kelp beds: patterns and processes. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 421:67–82

Krumhansl KA, Scheibling RE (2012) Production and fate of kelp detritus. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 467:281–302

Mabin CJ, Gribben PE, Fischer A, Wright JT (2013) Variation in the morphology, reproduction and development of the habitat-forming kelp Ecklonia radiata with changing temperature and nutrients. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 483:117–131

Macreadie PI, Anton A, Raven JA, Beaumont N, Connolly RM, Friess DA, Kelleway JJ, Kennedy H, Kuwae T, Lavery PS (2019) The future of blue carbon science. Nat Commun 10(1):1–13

Mann K (1973) Seaweeds: their productivity and strategy for growth. Science 182(4116):975–981

Mann E, Kirkman H (1981) Biomass method for measuring productivity of Ecklonia radiata, with the potential for adaptation to other large brown algae. Mar Freshwater Res 32(2):297–304

Millar RV, Houghton JD, Elsäßer B, Mensink PJ, Kregting L (2019) Influence of waves and currents on the growth rate of the kelp Laminaria digitata (phaeophyceae). J Phycol 56:198–207

Müller R, Laepple T, Bartsch I, Wiencke C (2009) Impact of oceanic warming on the distribution of seaweeds in polar and cold-temperate waters. Bot Mar 52(6):617–638

Ortega A, Geraldi NR, Alam I, Kamau AA, Acinas SG, Logares R, Gasol JM, Massana R, Krause-Jensen D, Duarte CM (2019) Important contribution of macroalgae to oceanic carbon sequestration. Nat Geosci 12(9):748–754

Painting S, Foden J, Forster R, van der Molen J, Aldridge J, Best M, Jonas P, Hydes D, Walsham P, Webster L (2013) Impacts of climate change on nutrient enrichment. Marine Climate Change Impacts Partnership Science Review, Lowestoft, UK, pp 219–235

Parke M (1948) Studies on British laminariaceae. I. Growth in Laminaria saccharina (L.) lamour. J Mar Biol Assoc UK 27(3):651–709

Pedersen MF, Filbee-Dexter K, Norderhaug KM, Fredriksen S, Frisk NL, Wernberg T (2020) Detrital carbon production and export in high latitude kelp forests. Oecologia 192(1):227–239

Pessarrodona A, Moore PJ, Sayer MD, Smale DA (2018) Carbon assimilation and transfer through kelp forests in the NE Atlantic is diminished under a warmer ocean climate. Glob Change Biol 24:4386–4398

Philippart CJ, Anadón R, Danovaro R, Dippner JW, Drinkwater KF, Hawkins SJ, Oguz T, O’Sullivan G, Reid PC (2011) Impacts of climate change on European marine ecosystems: observations, expectations and indicators. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 400(1–2):52–69

Pironon S, Papuga G, Villellas J, Angert AL, García MB, Thompson JD (2017) Geographic variation in genetic and demographic performance: new insights from an old biogeographical paradigm. Biol Rev 92(4):1877–1909

Queirós AM, Stephens N, Widdicombe S, Tait K, McCoy SJ, Ingels J, Rühl S, Airs R, Beesley A, Carnovale G (2019) Connected macroalgal-sediment systems: blue carbon and food webs in the deep coastal ocean. Ecol Monogr 89(3):e01366

Raybaud V, Beaugrand G, Goberville E, Delebecq G, Destombe C, Valero M, Davoult D, Morin P, Gevaert F (2013) Decline in kelp in West Europe and climate. PLoS ONE 8(6):e66044

Reed DC, Brzezinski MA (2009) Kelp forests. In: Laffoley D, Grimsditch G (eds) The management of natural coastal carbon sinks. IUCN, Gland, pp 31–37

Reed DC, Rassweiler A, Arkema KK (2008) Biomass rather than growth rate determines variation in net primary production by giant kelp. Ecology 89(9):2493–2505

Rinde E, Sjøtun K (2005) Demographic variation in the kelp Laminaria hyperborea along a latitudinal gradient. Mar Biol 146(6):1051–1062

Sagarin RD, Gaines SD (2002) The ‘abundant centre’ distribution: to what extent is it a biogeographical rule? Ecol Lett 5(1):137–147

Schaffelke B, Lüning K (1994) A circannual rhythm controls seasonal growth in the kelps Laminaria hyperborea and L. digitata from Helgoland (North Sea). Eur J Phyc 29:49–56

Sheppard C, Jupp B, Sheppard A, Bellamy D (1978) Studies on the growth of Laminaria hyperborea (gunn.) fosl. and Laminaria ochroleuca de la pylaie on the French channel coast. Bot Mar 21(2):109–116

Smale DA (2020) Impacts of ocean warming on kelp forest ecosystems. New Phytol 225:1447–1454

Smale DA, Pessarrodona A, King N, Burrows MT, Yunnie A, Vance T, Moore P (2020) Environmental factors influencing primary productivity of the forest-forming kelp Laminaria hyperborea in the northeast atlantic. Sci Rep 10(1):1–12

Smale DA, Wernberg T (2013) Extreme climatic event drives range contraction of a habitat-forming species. Proc Biol Sci 280(1754):20122829

Smale DA, Burrows MT, Moore P, O’Connor N, Hawkins SJ (2013) Threats and knowledge gaps for ecosystem services provided by kelp forests: a Northeast Atlantic perspective. Ecol Evol 3(11):4016–4038

Smale DA, Wernberg T, Yunnie AL, Vance T (2015) The rise of Laminaria ochroleuca in the western English Channel (UK) and comparisons with its competitor and assemblage dominant Laminaria hyperborea. Mar Ecol 36(4):1033–1044

Smale DA, Burrows MT, Evans AJ, King N, Sayer MD, Yunnie AL, Moore PJ (2016) Linking environmental variables with regional-scale variability in ecological structure and standing stock of carbon within UK kelp forests. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 542:79–95

Smale DA, Moore PJ, Queirós AM, Higgs S, Burrows MT (2018) Appreciating interconnectivity between habitats is key to blue carbon management. Front Ecol Environ 16(2):71–73

Smith SV (1981) Marine macrophytes as a global carbon sink. Science 211(4484):838–840

Sondak CF, Chung IK (2015) Potential blue carbon from coastal ecosystems in the republic of Korea. Ocean Sci J 50(1):1–8

Straub SC, Wernberg T, Thomsen MS, Moore PJ, Burrows M, Harvey BP, Smale DA (2019) Resistance to obliteration; responses of seaweeds to marine heatwaves. Front Mar Sci 6:763

tom Dieck I (1992) North Pacific and North Atlantic digitate Laminaria species (Phaeophyta): hybridization experiments and temperature responses. Phycology 31:147–163

Trevathan-Tackett SM, Kelleway J, Macreadie PI, Beardall J, Ralph P, Bellgrove A (2015) Comparison of marine macrophytes for their contributions to blue carbon sequestration. Ecology 96(11):3043–3057

Viejo RM, Martínez B, Arrontes J, Astudillo C, Hernández L (2011) Reproductive patterns in central and marginal populations of a large brown seaweed: drastic changes at the southern range limit. Ecography 34(1):75–84

Wernberg T, Russell BD, Thomsen MS, Gurgel CFD, Bradshaw CJ, Poloczanska ES, Connell SD (2011) Seaweed communities in retreat from ocean warming. Curr Biol 21(21):1828–1832

Wernberg T, Bennett S, Babcock RC, de Bettignies T, Cure K, Depczynski M, Dufois F, Fromont J, Fulton CJ, Hovey RK, Harvey ES, Holmes TH, Kendrick GA, Radford B, Santana-Garcon J, Saunders BJ, Smale DA, Thomsen MS, Tuckett CA, Tuya F, Vanderklift MA, Wilson S (2016) Climate-driven regime shift of a temperate marine ecosystem. Science 353(6295):169–172

Wernberg T, Coleman MA, Bennett S, Thomsen MS, Tuya F, Kelaher BP (2018) Genetic diversity and kelp forest vulnerability to climatic stress. Sci Rep 8(1):1–8

Yesson C, Bush LE, Davies AJ, Maggs CA, Brodie J (2015) The distribution and environmental requirements of large brown seaweeds in the British Isles. J Mar Biol Assoc UK 95(4):669–680

Funding

N.G.K. was funded by an Institute of Biological, Environmental and Rural Sciences PhD studentship. Funding for PJM was provided through a Marie Curie Career Integration Grant (PCIG10-GA-2011-303685) and NERC/Newton Fund Latin American Biodiversity Programme NE/SO11692/1. D.S. was supported by a UKRI Future Leaders Fellowship (MR/S032827/1).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Responsible Editor: M. Roleda.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Reviewed by I. Bartsch, G. Pearson and an undisclosed expert.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

King, N.G., Moore, P.J., Pessarrodona, A. et al. Ecological performance differs between range centre and trailing edge populations of a cold-water kelp: implications for estimating net primary productivity. Mar Biol 167, 137 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00227-020-03743-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00227-020-03743-5