Abstract

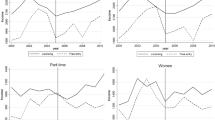

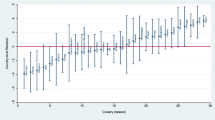

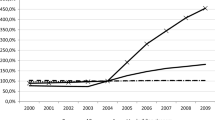

This paper uses the 2004 amendment to the German Trade and Crafts Code as a natural experiment for assessing the causal effects of this reform on the probabilities of being self-employed and of transition into and out of self-employment. This is achieved by using repeated cross-sections (2002–2009) of German microcensus data. I apply the difference-in-differences technique for three groups of craftsmen which were subject to different intensities of treatment. The results show that the complete exemption from the educational entry requirement has fostered self-employment significantly by substantially increasing the entry probabilities, while exit rates have remained unaffected. I find similar, though weaker relative effects for the treatment groups that were subject to a reduction of entry costs or a partial exemption from the entry requirements. Moreover, I consider effect heterogeneity within each of the treatment groups with respect to gender and vocational training, and show that the deregulation of entry requirements has been most effective for untrained workers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See Djankov et al. (2002) for a discussion of the theory of regulation.

This regulation was amended in the context of a series of reforms aimed at the German social system and labor market. See Blanchard and Giavazzi (2003) for a consideration of the interactions between product and labor market regulation.

The 57 trades similar to crafts referred to as \(B2\)-occupations below, are not subject of this analysis.

When a major amendment to the HwO reduced the number of regular craftsmanship occupations from 127 to 94 in 1998, the entry requirement for \(A\)-occupations remained untouched.

It is beyond the scope of this paper to measure whether the Meister degree provides relevant human capital. Therefore, the reader should be aware that the returns on this investment are highly contested.

This amendment is based on two laws, the greater amendment to HwO (Drittes Gesetz zur Änderung der Handwerksordnung und anderer handwerksrechtlicher Vorschriften) and the small amendment to HwO (Gesetz zur Änderung der Handwerksordnung und zur Förderung von Kleinunternehmen).

\(B2\)-occupations are not used as a control group because these occupations are not always discriminable in the dataset due to data protection.

Although \(B2\)-occupations are excluded from the analysis when the data set can distinguish them, some of these professions remain in the sample. Because they remain in the same group (e.g., \(B1\)) over the entire period, according to their time-invariant job definition, their presence in the sample does little harm. In fact, the results do not change if all occupational codes associated with more than one group, e.g., a \(B1\)-occupation and a \(B2\)-occupation, are excluded from the sample.

I assume that non-anticipating substitution across the groups is negligible and thus most of the treatment effect is caused by a higher rate of self-employment across groups. This assumption receives support from the observation that the stock of businesses increased from 2003 to 2004 in all three groups reported in Table 8.

See (Müller 2008) for initial empirical assessments of how the 2004 enlargement of the EU influenced German craftsmanship.

The post-policy period could be defined as the period from 2004 to 2009. However, the data from 2004 refer to the beginning of this year, which basically represents the status quo ante, so the post-policy period in the main specifications includes only the years 2005 and 2009. Results from a specification where the post-policy period is defined from 2004 to 2009 or 2004 is dropped are shown in Table 11. The post-policy dummy equals 1 for both years, which prevents the interaction effect from differing in the post-policy periods. A more flexible specification is presented in Table 12 and discussed in Sect. 5.4.

Craftsmanship has seven branches: (i) building and construction trades, (ii) electrical and metal-working trades, (iii) woodwork trades, (iv) clothing, textile and leather trades, (v) foodstuffs trades, (vi) trades related to health and hygiene, including chemical and cleaning trades, and (vii) glass, paper, ceramic, and other trades.

In particular including occupational fixed effects inflates standard errors because of multicollinearity.

Given the shortcomings of the LPM documented elsewhere, I prefer the logit models and present the LPM estimates for comparison.

The functional form imposed by the logit model is flatter than the linear function in the region where the probability of entry is low.

References

Aghion P, Blundell R, Griffith R, Howitt P, Prantl S (2009) The effects of entry on incumbent innovation and productivity. Rev Econ Stat 91(1):20–32

Ardagna S, Lusardi A (2009) Where does regulation hurt? Evidence from new businesses across countries. NBER Working Paper No. 14747

Ardagna S, Lusardi A (2010) Explaining international differences in entrepreneurship: the role of individual characteristics and regulatory constraints. In: Lerner J, Schoar A (eds) International differences in entrepreneurship, NBER Conference Report, University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London, pp 17–62

Baumgartner HJ, Caliendo M, Steiner V (2006) Existenzgründungsförderung für Arbeitslose: Erste Evaluationsergebnisse für Deutschland. Vierteljahrs. Wirtschaftsforschung 75(3):32–48

Bertrand M, Kramarz F (2002) Does entry regulation hinder job creation? Evidence from the French retail industry. Q J Econ 117(4):1369–1413

Bertrand M, Schoar A, Thesmar D (2007) Banking deregulation and industry structure: evidence from the French banking reforms of 1985. J Finance 62(2):597–628

Blanchard O, Giavazzi F (2003) Macroeconomic effects of regulation and deregulation in goods and labor markets. Q J Econ 118(3):879–907

Blanchflower DG, Oswald AJ (1998) What makes an entrepreneur? J Lab Econ 16(1):26–60

Blundell R, Costa Dias M (2009) Alternative approaches to evaluation in empirical microeconomics. J Hum Res 44(3):565–640

Branstetter LG, Lima F, Taylor LJ, Venâncio A (2013) Do entry regulations deter entrepreneurship and job creation? Evidence from recent reforms in Portugal. Econ J. doi:10.1111/ecoj.12044

Bruhn M (2011) License to sell: the effect of business registration reform on entrepreneurial activity in Mexico. Rev Econ Stat 93(1):382–386

Caliendo M, Künn S (2011) Start-up subsidies for the unemployed: long-term evidence and effect heterogeneity. J Public Econ 95(3–4):311–331

Caliendo M, Steiner V (2005) Aktive Arbeitsmarktpolitik in Deutschland: Bestandsaufnahme und Bewertung der mikroökonomischen Evaluationsergebnisse. Z Arb Markt Forsch 38(2–3):396–418

Cetorelli N, Strahan PE (2006) Finance as a barrier to entry: bank competition and industry structure in local U.S. markets. J Finance 61(1):437–461

Ciccone A, Papaioannou E (2007) Red tape and delayed entry. J Eur Econ Assoc 5(2–3):444–458

Djankov S, La Porta R, Lopez-De-Silanes F, Shleifer A (2002) The regulation of entry. Q J Econ 117(1):1–37

Evans DS, Jovanovic B (1989) An estimated model of entrepreneurial choice under liquidity constraints. J Polit Econ 97(4):808–827

Fossen FM (2011) The private equity premium puzzle revisited - New evidence on the role of heterogeneous risk attitudes. Economica 78(312):656–675

German Confederation of Skilled Crafts (2003) Stellungnahme zum Themenkatalog zur öffentlichen Anhörung des Ausschusses für Wirtschaft und Arbeit des Deutschen Bundestages, Berlin

German Confederation of Skilled Crafts (1991) Marktöffnung und Wettbewerb. Gutachten der unabhängigen Expertenkommission zum Abbau marktwidriger Regulierungen, Stuttgart

German Monopolies Commission (1998) Marktöffnung umfassend verwirklichen. Hauptgutachten der Monopolkommission, XII (1996/97), Baden-Baden

German Monopolies Commission (2002) Reform der Handwerksordnung. Sondergutachten der Monopolkommission, 31, Bonn

Holtz-Eakin D, Rosen HS (2005) Cash constraints and business start-ups: Deutschmarks versus Dollars. Contrib Econ Anal Policy 4(1):1–26

Hurst E, Lusardi A (2004) Liquidity constraints, household wealth, and entrepreneurship. J Polit Econ 112(2):319–347

Kerr WR, Nanda R (2009) Democratizing entry: banking deregulations, financing constraints, and entrepreneurship. J Finan Econ 94(1):124–149

King G, Zeng L (2001) Logistic regression in rare events data. Polit Anal 9(2):137–163

Klapper L, Laeven L, Rajan R (2006) Entry regulation as a barrier to entrepreneurship. J Finan Econ 82(3):591–629

Meyer BD (1995) Natural and quasi-experiments in economics. J Bus Econ Stat 13(2):151–161

Müller K (2006) Erste Auswirkungen der Novellierung der Handwerksordnung von 2004 Göttinger handwerkswirtschaftliche Studien 74. Mecke Druck und Verlag, Duderstadt

Müller K (2008) Auswirkungen der EU-Osterweiterung auf das deutsche Handwerk im Spiegel erster empirischer Erhebungen. In: Bizer K (ed) EU-Osterweiterung: Erste Zwischenbilanz für das Handwerk. Mecke Druck und Verlag, Duderstadt

Prantl S (2012) The impact of firm entry regulation on long-living entrants. Small Bus Econ 39(1):61–76

Prantl S, Spitz-Oener A (2009) How does entry regulation influence entry into self-employment and occupational mobility? Econ Transit 17(4):769–802

Puhani PA (2012) The treatment effect, the cross difference, and the interaction term in nonlinear ‘difference-in-differences’ models. Econ Lett 115(1):85–87

Rostam-Afschar D (2010) Entry regulation and entrepreneurship: empirical evidence from a German natural experiment. DIW Berlin Discussion Paper No. 1065

Sadun R (2008) Does planning regulation protect independent retailers? CEP Discussion Paper No. 888

van Stel A, Storey D, Thurik A (2007) The effect of business regulations on nascent and young business entrepreneurship. Small Bus Econ 28(2–3):171–186

Viviano E (2008) Entry regulations and labour market outcomes: evidence from the Italian retail trade sector. Lab Econ 15(6):1200–1222

Acknowledgments

I thank the editor, two anonymous referees, Viktor Steiner, Susanne Prantl, Alexandra Spitz-Oener, Frank Fossen, Justin Davies, and participants at the 67th European Meeting of the Econometric Society in 2013, at the annual meeting of the Verein für Socialpolitik in 2012, the 4th Ruhr Graduate School Doctoral Conference in Economics in 2011, the BeNA Leibniz Seminar on Labor Research in 2010, and the joint seminar of DIW Berlin and the Freie Universität of Berlin in 2010 and 2012 for valuable comments and suggestions. Financial support from the German Research Foundation (DFG) for the project “Tax Policy and Entrepreneurial Choice” (STE 681/7-1) is gratefully acknowledged. I thank the German Confederation of Skilled Crafts (ZDH) and the Berufsverband unabhängiger Handwerkerinnen und Handwerker (BUH) for insightful discussions. This paper is a substantial extension of the Diploma thesis of the author and has been circulated in an earlier version under the title “Entry Regulation and Entrepreneurship—Empirical Evidence from a German Natural Experiment”. The usual disclaimer applies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

See Tables 8, 9, 10, 11, and 12.

1.1 Description of key variables

- Entrepreneur::

-

Are you working as self-employed (with or without employees)? This definition includes non-incorporated self-employed as well as incorporated self-employed.

- \(B1\), \(A1\), \(A2\), \(AC\)::

-

Job title of most recent occupation. Occupational groups are constructed according to job titles in HwO.

- Policy::

-

Dummy indicating the post-policy period from 2005 to 2009.

- Entry, Exit::

-

Employment status in previous year. This non-mandatory question was included before 2005 for 0.45 % of the German population and for 1 % of the German population in 2005 and 2009.

- SPP::

-

Indicates receiving subsidies for self-employed. After excluding individuals eligible for child benefit, the dummy variable PP is restricted to all recently (assuming start-ups are subsidized for at most three years) self-employed individuals, who earn below 26,076 Euros (close to the 25,000 Euro threshold of the EXGZ) per year and receive public payments.

- EU::

-

Indicates citizenship of foreigners in a member state of the European Union (EU).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rostam-Afschar, D. Entry regulation and entrepreneurship: a natural experiment in German craftsmanship. Empir Econ 47, 1067–1101 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-013-0773-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-013-0773-7