Abstract

Purpose

Due to the lack of evidence, it was the aim of the study to investigate current possible cutbacks in orthopaedic healthcare due to the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic (COVID-19).

Methods

An online survey was performed of orthopaedic surgeons in the German-speaking Arthroscopy Society (Gesellschaft für Arthroskopie und Gelenkchirurgie, AGA). The survey consisted of 20 questions concerning four topics: four questions addressed the origin and surgical experience of the participant, 12 questions dealt with potential cutbacks in orthopaedic healthcare and 4 questions addressed the influence of the pandemic on the particular surgeon.

Results

Of 4234 contacted orthopaedic surgeons, 1399 responded. Regarding arthroscopic procedures between 10 and 30% of the participants stated that these were still being performed—with actual percentages depending on the specific joint and procedure. Only 6.2% of the participants stated that elective total joint arthroplasty was still being performed at their centre. In addition, physical rehabilitation and surgeons’ postoperative follow-ups were severely affected.

Conclusion

Orthopaedic healthcare services in Austria, Germany, and Switzerland are suffering a drastic cutback due to COVID-19. A drastic reduction in arthroscopic procedures like rotator cuff repair and cruciate ligament reconstruction and an almost total shutdown of elective total joint arthroplasty were reported. Long-term consequences cannot be predicted yet. The described disruption in orthopaedic healthcare services has to be viewed as historic.

Level of evidence

V.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The rapidly expanding novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), is currently challenging the medical community all over the world. Following the concept of ‘Better Safe than Sorry’, many countries are reserving medical resources for COVID-19 patients. In the field of orthopaedic surgery, many elective surgeries and outpatient visits have been postponed. However, the authors are not aware of published investigations that would document the precise situation of orthopaedic healthcare disruption in particular countries.

By contrast, cutbacks in healthcare services due to the COVID-19 pandemic were already reported by other medical disciplines in recent weeks. Angelico et al. reported a reduction in major organ transplantations of at least 25% over the last weeks due to the reduced availability of beds at the intensive care unit [1]. Connor et al. worried about the implications of the pandemic for urology patients, especially those with malignant disease [3]. Although attempts were made by telemedicine to compensate for the cancellation of all outpatient activities, the authors were concerned about delivering a primary diagnosis of malignant disease via telemedicine. Colorectal surgeons reported that their workload was reduced in all aspects of patient care [7]. They stated that the reduction in case numbers had a profound impact on their daily practice.

It was the aim of the present survey to investigate a possible cutback in orthopaedic healthcare by conducting an online survey of orthopaedic surgeons of the AGA-Society of Arthroscopy and Joint-Surgery, whose members are mainly located in the German-speaking countries of Europe. Over 100 million people live in the German-speaking countries Austria, Germany and Switzerland, representing approximately one-seventh of Europe’s population.

Materials and methods

Study design was a prospective online survey of orthopaedic surgeons (expert opinion).

All participants were members of the AGA-Society of Arthroscopy and Joint-Surgery (Gesellschaft für Arthroskopie und Gelenkchirurgie, AGA, www.aga-online.ch), to date Europe’s largest arthroscopy society with 5339 members. Of the members, 4234 were orthopaedic surgeons who were considered for participation. Approval by an institutional review board was deemed unnecessary since no patient data were involved.

The survey was created with SurveyMonkey (https://www.surveymonkey.com), an online data collection program. The survey consisted of 20 questions on 4 topics: 4 questions addressed the origin and surgical experience of the participant, 12 questions dealt with potential cutbacks in orthopaedic healthcare and four questions addressed the influence of the pandemic on the particular surgeon. Of the whole questionnaire, twelve questions offered multiple response options, while six questions offered only one option. For the demographic question, a drop-down menu was created for the country and state. For the particular surgical procedures, a matrix with four different response options was created, with only one response possible per procedure (see Online Appendix 1 for survey details).

A link to the survey was then sent by email to the above-mentioned 4234 orthopaedic surgeons in the German-speaking Arthroscopy Society on 30 March 2020. Every second day those who had not yet responded received a reminder email. The online survey was finally closed on 5 March 2020. 1399 of the 4234 surgeons participated (33%). A participation rate of one-third within 1 week is regarded as reasonable in times when so many of us are facing new challenges daily.

Results

A total of 1399 orthopaedic surgeons participated in the online survey; 15.7% of the surgeons worked in Austria, 13.3% in Switzerland and 71.0% in Germany. While 11.3% worked in an academic centre, 47.9% worked in a non-academic public hospital, 27.6% in a private hospital and 38.3% were running a private practice. Of the participants, 27.7% had more than 20 years of experience as a physician (including residency); 21.3% and 14.7% of the surgeons reported > 15 and > 10 years experience, respectively.

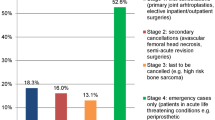

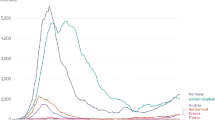

Regarding potential disruption of orthopaedic services, 20.4% of the participants reported that all surgical procedures had been cancelled at their work place. Of the participants, 59.9% stated that elective inpatient procedures were no longer possible, and 53% reported that all outpatient procedures had to be cancelled (Fig. 1). Nearly all (91.1%) orthopaedic surgeons communicated that their personal surgical volume was drastically reduced—giving a free capacity that was used to perform more administrative work than usual (41.5% of participants). However, 21.1% were even assigned to non-orthopaedic duties (Fig. 2).

Regarding arthroscopic procedures, only between 10 and 30% of the participants stated that these were still being performed, with current percentages depending on the specific joint and procedure. Only 6.2% of the participants stated that elective total joint arthroplasty was still being performed at their centre. Of the participants, 11.8% disclosed that aseptic revisions of arthroplasty were still being performed, while 25% stated that anterior cruciate ligament reconstructions were still being offered to patients. Approximately 50% of the participants reported that rotator cuff repair was no longer being performed. Hardly any participants (< 1%) reported that even femoral fractures or sarcoma patients were postponed (Table 1, Fig. 3). Regarding postoperative follow-ups, 11.9% of the surgeons communicated that they were no longer following their operated patients, 26.5% stated that postoperative follow-ups were being performed only in high-risk patients and 57.1% and 53.5% reported that they were still doing normal clinical and radiologic follow-ups, respectively. Physical therapy was also reported to be significantly impaired. Only 35.1% of the participants stated that their patients still had access to outpatient physical therapy. Rehabilitation centres were reported as still being functional by only 19.4% of the participants.

Responses to questions beyond the issue of treating patients were as follows: 52.5% of the participants stated that they already had SARS-CoV-2-positive patients in their departments. SARS-CoV-2 positivity of colleagues was reported by 41.6%. It was disclosed by 43.1% of the surgeons that professional meetings and conferences were still being held but with reduced staff, while 20.7% reported that the whole staff still participated in meetings but practised social distancing, while 8.1% were meeting in teleconferences only.

Of the surgeons, 13.2% stated that they were trying to keep a distance to their families, 8.6% reported that they were avoiding physical contact with their families, and 6.6% performed surface disinfection at home.

Of the surgeons, 4.7% now live in separate rooms at home, 2.8% stated that they no longer go home, and 11% were on vacancy during the pandemic, while 2.8% do not care at all whether they infect their family. Responses show that 81% now wash and disinfect their hands more frequently, while 74.8% act more carefully at work.

Discussion

The most important findings of our survey study were that there were drastic disruptions in orthopaedic healthcare services in Austria, Germany and Switzerland. A drastic reduction in arthroscopic procedures like rotator cuff repair or cruciate ligament reconstruction was reported. Likewise, there was an almost total shutdown of elective total joint arthroplasty. About 20% of the surgeons stated that all orthopaedic surgeries were stopped at their working places. Physical rehabilitation and surgeons’ postoperative follow-ups were also reported to be severely impaired. The described disruption of orthopaedic healthcare services in Austria, Germany and Switzerland has to be viewed as historic. Even among surgeons with more than 20 years of professional experience such a disruption was deemed unprecedented. It can be assumed that the only other similar scenario was the disruption in orthopaedic patient care that occurred during World War II.

When attempting to compare our study with others it appears that, to our very best knowledge, only one study about the effects of the COVID-19 epidemic on orthopaedic healthcare services has been conducted so far [9]. That study by Thaler et al. investigated potential disruptions in joint arthroplasty services all across Europe. Similar to our study, the authors used an online survey to ask arthroplasty surgeons of (a) the European Hip Society and (b) the European Knee Associates about cutbacks in total joint arthroplasty. Thaler et al. reported that of the 272 participants, only 5.9% were still able to offer primary elective total joint arthroplasty. Aseptic arthroplasty revisions were reported by 3.8% of the participants to still be taking place. They further communicated that 87.2%, 75.6% and 25.8% of their survey participants were operating on periprosthetic fractures, doing septic arthroplasty revisions and tumour arthroplasties, respectively. Taken together, the results of the study by Thaler et al. were quite congruent with the findings of this study. This is to say that only fractures, malignancies and severe infections are being treated surgically. However, the comparability of the two studies might be impaired because the study at hand consulted mainly surgeons preferring sports orthopaedics, while Thaler et al. consulted mainly arthroplasty surgeons. Another aspect possibly influencing comparability is that in our study, the participants’ origin was Austria, Germany and Switzerland, while the other study included surgeons from all over Europe.

It was previously shown that postponing orthopaedic procedures not only means prolonged pain, but may even lead to poorer outcome overall. For example, Mossmayer et al. prospectively followed 103 patients with rotator cuff tears over 10 years and found that those with delayed repair had significantly poorer results than did those who underwent early repair—an effect that became even worse from year to year [8].

When trying to compare our investigation with studies from fields other than orthopaedic surgery, we find evidence from Angelico et al. from the special field of organ transplantation [1]. Similar to the cutbacks in orthopaedic surgery, a reduction of at least 25% in major organ transplantation was reported over recent weeks. According to Angelico et al., that cutback was due to the fact that beds at the intensive care units were reserved for COVID-19 patients. Connor et al. [3] worried about the implications of the pandemic for urology patients, especially those with malignant disease. The authors stated that they tried by telemedicine to compensate for the cancellation of all outpatient activities, but were concerned about delivering a primary diagnosis of malignant disease via telemedicine. Colorectal surgeons reported that their workload was reduced in all aspects of patient care. They stated that the reduction in case numbers had a profound effect on their healthcare services [7].

One study reported the consequences of COVID-19-related social distancing on the economy, society and mental health [2]. However, no publication has described the impact of the pandemic on the social life of physicians. It is demonstrated by the findings of the study that the pandemic is having a huge impact on the behaviour of orthopaedic surgeons towards their families at home. Only 2% of the survey participants reported making no changes in their behaviour at all, while 29.3% of our surgeons reported isolating themselves in different ways at home (13.2% kept distance to other family member, 8.6% avoided physical contact, 4.7% lived in separate rooms at home, 2.8% no longer went home, because they were afraid to harm their family). Because healthcare professionals like physicians are at risk of contracting COVID-19 [6], orthopaedic surgeons in Austria, Germany and Switzerland are obviously trying to protect their families from the disease and, therefore, are declining to have physical contact with them or even see them. Hence, 40.3% of all ticked response options showed some kind of self-imposed social distancing at home. Approximately 11% kept a distance to their hospital or private practice because of the pandemic, potentially also related to a shortage of appropriate personal protective equipment [5].

Several limitations of the study have to be acknowledged. First, the findings from the German-speaking countries in central Europe cannot be 100% extrapolated to other countries with other healthcare systems, like the US or China. Second, our survey may not be absolutely well balanced, because all participants were members of the ‘AGA-Society of Arthroscopy and Joint-Surgery’ and, therefore, the majority of them might have a more sports orthopaedic interest. In other words, arthroplasty surgeons may have been underrepresented in our survey.

It is regarded as a strength of the study that the high number of 1399 orthopaedic surgeons from the German-speaking countries participated. Over 100 million people live in the German-speaking countries Austria, Germany and Switzerland, representing approximately one-seventh of Europe’s population. The survey should, therefore, be regarded as providing robust information on the situation of orthopaedic healthcare disruption due to the COVID-19 epidemic.

It may well be speculated that the above-mentioned disruption does not just mean a simple delay in orthopaedic healthcare service. Instead, it must be assumed that due to the fact that surgical treatment cannot occur in a timely manner also the final outcome is impaired (e.g. meniscal repair performed 3 months later than usual). For orthopaedics, the way ahead is not clear and may substantially vary between different countries. But, it is most likely that as soon as a decline of new COVID-19 cases will occur in a country, a cautious and gradual resumption of routine orthopaedic procedures will be initiated [4]. However, it is believed by the authors that orthopaedic surgery will not be able to return to a pre-pandemic level earlier than within 3 months.

Conclusions

Orthopaedic healthcare services in Austria, Germany and Switzerland are suffering a drastic cutback due to COVID-19. A drastic reduction in arthroscopic procedures like rotator cuff repair and cruciate ligament reconstruction and an almost total shutdown of elective total joint arthroplasty were reported. Long-term consequences cannot be predicted yet. The described disruption in orthopaedic healthcare services has to be viewed as historic.

References

Angelico R, Trapani S, Manzia TM, Lombardini L, Tisone G, Cardillo M (2020) The COVID-19 outbreak in Italy: initial implications for organ transplantation programs. Am J Transplant. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajt.15904

Cao W, Fang Z, Hou G, Han M, Xu X, Dong J et al (2020) The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Res 287:112934

Connor MJ, Winkler M, Miah S (2020) COVID-19 pandemic—is virtual urology clinic the answer to keeping the cancer pathway moving? BJU Int. https://doi.org/10.1111/bju.15061

de Caro F, Hirschmann MT, Verdonk P (2020) Returning to orthopaedic business as usual after COVID-19: strategies and options. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-020-06031-3

Hirschmann MT, Hart A, Henckel J, Sadoghi P, Seil R, Mouton C (2020) COVID-19 coronavirus: recommended personal protective equipment for the orthopaedic and trauma surgeon. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-020-06022-4

Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, Cai Z, Hu J, Wei N et al (2020) Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open 3:e203976

Lisi G, Campanelli M, Spoletini D, Carlini M (2020) The possible impact of COVID-19 on colorectal surgery in Italy. Colorectal Dis. https://doi.org/10.1111/codi.15054

Moosmayer S, Lund G, Seljom US, Haldorsen B, Svege IC, Hennig T et al (2019) At a 10-year follow-up, tendon repair is superior to physiotherapy in the treatment of small and medium-sized rotator cuff tears. J Bone Jt Surg Am 101:1050–1060

Thaler M, Khosravi I, Hirschmann MT, Kort NP, Zagra L, Epinette JA, Liebensteiner MC (2020) Disruption of joint arthroplasty services in Europe during the COVID-19 pandemic: an online survey within the European Hip Society (EHS) and the European Knee Associates (EKA). Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-020-06033-1

Acknowledgements

The Board of the German-speaking Arthroscopy Society (AGA): Philipp Heuberer, HealthPi Medical Center, Vienna, Austria; Philipp Niemeyer, Orthopädische Chirurgie München, Munich, Germany; Helmut Lill, Diakovere Krankenhaus gGmbH, Hanover, Germany; Christoph Lampert, Orthopädie Rosenberg, St. Gallen, Switzerland; Florian Dirisamer, Orthopädie&Sportchirurgie, Linz-Puchenau, Austria; Sepp Braun, Gelenkpunkt-Sport-und Gelenkchirurgie, Innsbruck, Austria; Tomas Buchhorn, Sporthopaedicum, Straubing, Germany; René el Attal, Landeskrankenhaus Feldkirch, Feldkirch, Austria; Christian Jung, Schulthess Klinik, Zürich, Switzerland; Andreas Marc Müller, Unversitätsspital, Basel, Switzerland; Sven Scheffler, Sporthopaedicum Berlin, Berlin, Germany; Johannes Zellner, Caritas Krankenhaus St. Josef, Regensburg, Germany

Funding

There is no funding source.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

MCL was responsible for data collection and manuscript writing. IK wrote the survey, helped during writing of the manuscript by providing results, figures and table. MTH performed a revision of the manuscript. PRH was responsible for the data collection and also reviewing the manuscript. MT provided the concept of the study and developed the survey. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Details of the members of The Board of the German-speaking Arthroscopy Society (AGA) is given in "Acknowledgements".

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Liebensteiner, M.C., Khosravi, I., Hirschmann, M.T. et al. Massive cutback in orthopaedic healthcare services due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 28, 1705–1711 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-020-06032-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-020-06032-2