Abstract

Previous literature has established that lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) people are at least as likely to be poor as heterosexual people, standing in contrast to myths of “gay affluence.” These findings have used datasets limited by either sample size or using partnership status to infer sexual orientation. Using U.S. data from the Household Pulse Survey, which allows us to identify large samples of individuals who self-identify as lesbian, gay, or bisexual, we find that bisexuals have lower incomes and are more likely to experience poverty, and bisexual individuals, gay men, and lesbian women are more likely to report financial hardship. Additionally, we find that LGB people utilize government assistance at higher rates than heterosexual people, even when allowing for selection into poverty status. We propose several explanations for these differentials, drawing on the program non-participation literature, and suggest that social network effects, lessened stigma, and increased reliance on public programs may explain these differences. Finally, we examine receipt of the enhanced child tax credit and find evidence that gay men and lesbian women with children were less likely to receive it than heterosexual men and women with children.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

A large body of research has documented that sexual minorities (e.g., lesbian women, gay men, and bisexual populations—henceforth referred to as LGB individuals) have worse economic outcomes than heterosexuals, with lower incomes, higher rates of poverty, lower rates of health insurance coverage, and lower rates of homeownership (Albelda et al. 2009; Badgett et al. 2021; Elton and Gonzales 2022; Gonzales and Blewett 2014; Leppel 2007; Uhrig 2015). Additionally, some literature has examined utilization of government assistance programs by sexual orientation, typically used as a proxy for economic distress (Brown et al. 2016; Everett and Mollborn 2014; Schneebaum and Badgett 2019). These studies generally find elevated rates of government assistance receipt for LGBT individuals.

Tangentially, there is also large literature in public economics examining the delivery, take-up, receipt, and utilization of public assistance programs (e.g., SNAP, Unemployment Insurance). Nearly all public assistance programs do not have perfect take-up among eligible recipients, and these take-up rates can be crucial for projecting the aggregate costs and impacts of government assistance programs, as well as evaluating the welfare implications of policies that have already been implemented (Currie 2004; Finkelstein and Hendren 2020; van Oorschot 1991). Several possible explanations have been proposed for the drivers of imperfect take-up, including low monetary gains, stigma of receipt, time costs associated with program participation, imperfect information, administrative barriers, and mismeasurement (Ko and Moffitt 2022). Alternatively, it is possible that differences in access and take-up to government assistance programs can drive or amplify economic disparities experienced by marginalized populations. We open a dialogue between these subject areas and add novel evidence to the large body of public economic literature by identifying differential take-up of public assistance programs between LGB and heterosexual adults and proposing several explanations for future research to examine.

Understanding the economic position and receipt of government assistance among sexual minorities is important for several reasons. First, sexual minorities comprise a large and increasing share of the American population, and sexual minorities have gained much-needed recognition in public policy. Yet, there are substantial and ongoing policy implications that can be informed by LGB differentials in government assistance take-up, given the magnitude of economic costs that could occur. Badgett et al. (2021) report several estimates in the United States, finding that 2.7–4.6% of the American adult population identifies as non-heterosexual. Recent analyses have found that 15–20% of high school students identify as non-heterosexual (Gonzales and Deal 2022; Wilson and Meyer 2021). These estimates imply that there may be large policy implications that proceed from LGB differentials in government assistance take-up, given the magnitude of costs that could occur. Second, some public assistance programs are designed to benefit certain demographic characteristics and family structures (Hoffman 2008; Hussey 2011). LGB people may differentially receive or utilize public assistance programs, given that their demographic characteristics differ dramatically from heterosexuals (Brewster et al. 2014). In this respect, our analysis points towards a growing literature on population-targeted policies—such as the Affordable Care Act—and their differential effects on LGB individuals (Carpenter et al. 2021; Carpenter and Sansone 2021; Marcén and Morales 2022).Footnote 1

Prior research on LGB poverty and government assistance receipt has been limited by small sample sizes and the necessity of using same-sex couple status to infer sexual orientation (which excludes single sexual minorities and bisexual individuals and may lead to unrepresentative estimates) (Albelda et al. 2009; Badgett et al. 2013; Badgett 2018; DiBennardo and Gates 2014; Schneebaum and Badgett 2019; Uhrig 2015). Related work examines LGB disparities in several key economic vulnerability measures during the pandemic, including pandemic-related job loss, food insufficiency, and housing insecurity, finding broad negative differentials in economic security for LGB adults (Martell and Roncolato 2022). We leverage the large sample sizes of self-identified sexual minorities in the U.S. Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey (HPS) to evaluate the economic outcomes and government assistance receipt of sexual minorities relative to their heterosexual counterparts. We are among the first, to the best of our knowledge, to examine differences by sexual orientation across subjective measures of economic status. Additionally, we evaluate several government assistance programs that have not previously been examined in the context of differences by sexual orientation: the child tax credit, unemployment insurance, rental assistance, and stimulus payments. We also examine whether government assistance differentials for sexual minorities are homogeneous for bisexual and lesbian/gay individuals, identifying disparities that may face a subset of sexual minorities but be obscured in overall figures. Finally, we use data collected during the COVID-19 pandemic, a period of heightened economic distress when government assistance programs were increasingly utilized across the population. Evaluating the receipt and utilization of public assistance programs by sexual orientation is crucial for policymakers that must consider the potential for heterogeneous effects of policy on different communities, especially those with a history of worse economic outcomes.

We report several key results. We find that bisexuals have lower incomes and are more likely to report household incomes below the federal poverty level (FPL) than heterosexuals. Similarly, gay men, lesbian women, and bisexual individuals self-report higher economic insecurity than heterosexuals. Additionally, we find that sexual minorities are more likely to receive and utilize government services than heterosexuals. Differences in receiving government assistance persist when allowing for selection into FPL status, and we find evidence of higher utilization among gay and bisexual men compared to heterosexual men when restricting to a subsample of individuals who report household incomes below the FPL. We explore several potential reasons for this differential in our discussion, including social network effects, stigma differences surrounding the use of public assistance, and education differences. Finally, we evaluate receipt of the child tax credit by sexual orientation and find that gay men and lesbian women are less likely to receive the child tax credit than their heterosexual peers, even after adjusting for the presence of a child in the household and the total number of children in the household. This difference holds even for the subsample of individuals who report household incomes below the FPL.

The remainder of the paper takes the following form. Section 2 reviews previous literature on sexual minority economic status, as well as access to and utilization of government assistance programs. Section 3 develops a conceptual framework for LGB differentials in public assistance take-up and access. Section 4 describes our data and empirical approach. Section 5 presents the results, and Sect. 6 concludes.

2 Literature review

2.1 Poverty

The U.S. Census Bureau measures poverty by comparing a person or family’s household income to a threshold dependent on family size (Brady 2005). One avenue through which the U.S. government addresses poverty is public assistance programs, including cash support, provision of necessities (e.g., health insurance and funding to subsidize food or housing), and employment programs.

Due to discrimination, structural racism, and historical inequities, minority groups are often disproportionally affected by poverty and have reduced access to public resources (Horsfall 2012). For example, people with disabilities and Hispanic people are less likely to participate in programs like SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program), often because they do not know about benefits or are unable to navigate the enrollment process (Alvira-Hammond and Gennetian 2015; Keith-Jennings et al. 2019).

The theoretical impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on poverty is unclear. While the pandemic certainly interrupted the economy, causing widespread unemployment and economic distress for families, the federal government responded with historic public assistance efforts like the advance CTC, Paycheck Protection Program, and pausing Medicaid disenrollment. This is observed in previous empirical analyses of economic well-being, which have broadly found that pandemic-related government policy effectively countered its effects on incomes, leading poverty to fall and the household income of poorer households to rise across a range of demographic groups and geographies (Han et al. 2020; Martell and Roncolato 2022).

2.2 LGB economic and poverty status

Several economic studies have documented income differentials and penalties for sexual minorities. Gay and bisexual men have lower average incomes than do heterosexuals, whereas differentials for lesbian and bisexual women vary by study (Badgett et al. 2021; Drydakis 2022; Plug and Berkhout 2004). Earnings may be as much as 16% lower for gay men and 15% higher for lesbian women compared to their heterosexual counterparts (Ahmed and Hammarstedt 2010; Klawitter 2015); it is likely that the disparities observed for gay and bisexual men are due to taste-based discrimination, a finding that has been reinforced by audit studies (Badgett 1995; Patacchini et al. 2015; Tilcsik 2011). Additionally, prior literature has indicated that certain subpopulations of the LGB community, especially bisexuals, are more likely to experience poverty than heterosexuals (Badgett 2018). The same pattern does not hold, however, for lesbian women and gay men, who are less likely to experience poverty than heterosexuals (Badgett 2018; Uhrig 2015). This bisexual poverty differential may proceed from compositional differences, as bisexual men and women tend to be younger, have lower educational attainment, and are more likely to be never married and unpartnered compared to both their heterosexual and gay/lesbian counterparts, all characteristics associated with higher relative risk of poverty (Badgett 2018). Additionally, we find that bisexual men and women are more likely to have children, increasing their relative risk of poverty. However, there is also a growing literature examining bisexual health that proposes a role for “double discrimination,” whereby bisexual individuals experience stigma and minority stress from both within and beyond the LGBTQ community (Colledge et al. 2015; Feinstein and Dyar 2017). It is possible that this stressor may contribute to the unique disparities in economic outcomes that bisexual individuals experience.

Several factors may exacerbate these disparities. Gay and bisexual men without children experience higher poverty rates than heterosexuals without children and the children of same-sex couples are twice as likely to be poor than children of different-sex married couples (Albelda et al. 2009). Comparing across race and location yields discrepancies in poverty rates as well. African American same-sex couples are much more likely to experience poverty than White same-sex couples. LGB African Americans experience poverty at least twice as much as their heterosexual counterparts (Badgett et al. 2013). Finally, same-sex couples in rural areas have a poverty rate that is twice that of those in metropolitan areas (Albelda et al. 2009).

Beyond labor market outcomes, other factors can influence an individual’s well-being. Perceived financial insecurity and risk are alternative measures of economic health that may offer a more comprehensive account (Western et al. 2012). Negative labor market outcomes tend to spillover to overall well-being, suggesting that we may expect negative financial well-being differentials for LGB populations compared to heterosexuals. For example, American LGB populations are also disproportionally food insecure (Brown et al. 2016). Previous research has also found elevated levels of economic insecurity among sexual minority men (Chai and Maroto 2020; Mann et al. 2019).

2.3 LGB government assistance

Less data is available on LGB access to government assistance due to the lack of questions regarding sexual orientation and gender identity in past surveys. One analysis suggests that same-sex couples—especially men in same-sex couples—access public health insurance at a higher rate (Badgett et al. 2006). Additionally, other analyses have found higher rates of cash assistance receipt among sexual minorities (Badgett et al. 2013; Uhrig 2015). Prior studies typically use receipt of public assistance as a proxy for poverty status and economic well-being.

3 Conceptual framework

Economic modelling of non-participation in public assistance programs generally ascribes the behavior to some combination of stigma, imperfect information, access costs outweighing participation benefits, and social networks (Currie 2004). For example, stigma was introduced first as a general disutility associated with program participation, and then this model was expanded to include a broader cost/benefit framework (Moffitt 1983). Additionally, a large empirical and theoretical literature has documented and modelled social network effects in program participation (Aizer and Currie 2004; Bertrand et al. 2000; Borjas and Hilton 1996; Manski 1993). Geographic and social networks can facilitate increased take-up of public assistance programs. Information barriers can also keep eligible potential recipients from realizing their eligibility (Ko and Moffitt 2022). We use these models of non-participation and prior work on the demographic characteristics of LGB populations to generate predictions for the public assistance take-up of this group.

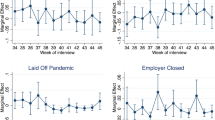

Several demand-side mechanisms may lead to increased public assistance participation for LGB adults. LGB individuals are more likely to be in poverty than heterosexual individuals and are resultantly more likely to qualify, receive, and utilize government assistance to support their economic conditions. In fact, some previous studies have used receipt of government assistance as a proxy for poverty and economic distress (Badgett 2018; Badgett et al. 2006; Uhrig 2015).Footnote 2 In addition to pre-existing vulnerabilities, another possibility is that LGB individuals may have been differentially affected by the COVID-19 pandemic and so may be more likely to be unemployed and require government assistance as a result. Gonzales and Loret de Mola (2021) found that sexual minorities were more likely to be working in COVID-19-sensitive industries, which would support the hypothesis that they are more vulnerable to employment disruptions (and subsequently need more assistance) caused by the COVID-19 pandemic than otherwise similar heterosexuals. Additionally, Martell and Roncolato (2022) found that lesbian women, bisexual women, and bisexual men were more likely than their heterosexual counterparts to be in a household that experienced pandemic related job loss. These demand-side explanations suggest that LGB people may have higher public assistance take-up due to a higher need for support.

However, we might also find differentially larger take-up of government assistance programs by LGB individuals compared to similarly situated heterosexual individuals. Why might this be the case?

Information barriers are a common explanation for program non-participation and can be mitigated by education (Currie 2004). Sexual minority adults are more likely to have college and advanced degrees than heterosexuals (Black et al. 2007; Carpenter and Gates 2008; Gonzales and Blewett 2014). More educated individuals may be more likely to be aware of and navigate bureaucratic hurdles to government assistance programs, thus enabling them to take up the programs at higher rates by reducing information barriers and access costs. Now, we turn to two other possibilities: stigma and a lack of other support networks.

Another factor that influences participation in government assistance programs is stigma surrounding the receipt and utilization of public assistance programs (Allen et al. 2014; Fothergill 2003; Stuber and Schlesinger 2006). Some individuals who qualify for benefits may not choose to use them due to political views or principles surrounding whether the government should provide such benefits (Morin et al. 2012). Ample social science research has found that sexual minorities tend to align with left-leaning parties and support liberal policy positions, suggesting that they may not share this stigma to the same degree as heterosexual populations (Edelman 1992; Jones 2021; Lewis et al. 2011; Smith and Haider-Markel 2002; Turnbull-Dugarte and Townsley 2020). The stigma hypothesis of higher support for and willingness to use government assistance programs suggests a positive public assistance take-up differential for sexual minorities.

A lack of alternative community-based and familial networks for low-income LGB people may indicate they have to rely on government assistance more than similarly situated heterosexuals. Previous research has established that LGB people are less likely to be affiliated with organized religion, which is one pathway through which individuals can acquire social and economic supports (Herek et al. 2010; Sherkat et al. 2010). Additionally, the family strains involved in the coming out process or a lack of family acceptance may lead to decreased social or economic support from immediate and extended family members, though some work has found higher financial transfers from parents to LGB children than heterosexual children (Dempsey et al. 2020; Perales and Huang 2020). Government assistance may be filling in gaps for low-income LGB people where they lack support structures that low-income heterosexuals have, again predicting higher take-up among sexual minorities (Wilson et al. 2020).

Finally, it is possible that differentials are due to social network effects. Sociologists have established that individuals’ choices can be influenced by their peers, and that these “social networks” can shape behavior both consciously and unconsciously (DiMaggio and Garip 2012). Additionally, some literature has found that subgroups of the LGB community have denser (non-familial) social networks than heterosexuals (Breder and Bockting 2022). It is possible that LGB individuals in poverty may be referring each other to social service access differentially, or have access to social service providers and assistance through networks like sexual health clinics for HIV and STI care, which frequently offer comprehensive services alongside sexual health screenings and treatments (AIDS Project LA 2022). Additionally, individuals with HIV may automatically qualify for SSI and Medicaid if their health deteriorates to disabling levels.

Using the frameworks outlined above and the contextual details of the LGB community, we expect that LGB adults will take-up public assistance programs at higher rates than similarly eligible heterosexual adults.

4 Data/methods

4.1 The household pulse survey

Data for our study are drawn from waves 3.2–3.4 (weeks 34–43) of the Household Pulse Survey (HPS), a nationally representative and repeated cross-section of approximately 70,000 households in the 50 U.S. states and the District of Columbia. Respondents are surveyed in short waves that the US Census Bureau calls “weeks,” usually spanning 12–15 days and surveying approximately 70,000 households. We combine these weeks to improve statistical power and, after applying sample restrictions (outlined further below), we have a primary analytic sample of 523,796 respondents, including 19,007 gay or lesbian individuals, as well as 19,290 bisexual individuals. The HPS was designed to measure rapid responses to the COVID-19 pandemic; thus, the HPS is a rich source of information on how the pandemic affected health, finances, income security, and utilization of public assistance programs. These data were collected and made publicly available through the U.S. Census Bureau and contain demographic, economic, social, and housing information. As a large household survey administered by the U.S. Census Bureau in conjunction with other agencies, the large sample sizes of the HPS make it particularly germane to studying subpopulations like low-income individuals and/or the LGB population. Other researchers have used these data to examine the social safety net (Bitler et al. 2020), education supply (Bansak and Starr 2021), and consumer behavior (Garner et al. 2020).

The HPS is one of the only large national surveys that directly asks respondents about their sexual orientation. Respondents are given the prompt: “Which of the following best represents how you think of yourself?” and they can answer (1) Gay or lesbian; (2) Straight, that is not gay or lesbian; (3) Bisexual; (4) Something else; and (5) I don’t know. This question was added to the questionnaire in week 34, so we used data from weeks 34–43, which were fielded in August 2021 through March 2022. We focus on those respondents who indicated that they were (1) Gay or lesbian or (2) Bisexual, which we designate as sexual minorities for our analysis. This direct question ascertaining sexual orientation identity is preferred to inferring sexual orientation through same-sex couple status due to issues of representativeness and capture (Carpenter et al. 2021; Martell 2021). The HPS also asks individuals about their gender identity using a two-step process. We use this information to control for gender identity but focus our analysis on differences by sexual orientation.Footnote 3 For more information on gender minority economic outcomes in the Household Pulse Survey, see C. S. Carpenter et al. (2022).

Regarding economic outcomes, participants self-report their employment status and household income in ranges. Specifically, all individuals report whether they worked for pay or profit in the last 7 days and their 2020 household income in ranges (less than $25,000; $25,000–$34,999; $35,000–$49,999; $50,000–$74,999; $75,000–$99,999; $100,000–$149,999; $150,000–$199,999; $200,000 and above). We examine household income directly, as well as poverty status, which is based on household income and household size (individuals are asked to state the number of adults and the number of children in the household; further information about the construction of this variable can be found in Appendix Table 2). The income-based thresholds used to determine the federal poverty level status of an individual come directly from the U.S. Census Bureau, where these thresholds were used to estimate the official poverty rate in the US (Creamer et al. 2022). However, eligibility for programs administered by the Department of Health and Human Services, including Medicare, Medicaid, CHIP, SNAP, and TANF, is determined using the federal poverty guidelines (FPG), a slightly different definition of poverty (2022). Both calculations consider the household composition and income, but the FPL also considers elderly status in determining poverty. As a result, our estimates of FPL status do not perfectly capture the factors that determine eligibility for some government assistance programs. Additionally, because we are using the midpoint of the income category that respondents report to determine poverty status, there is potential for mismeasurement as respondents whose exact income (which is unobserved) falls above the midpoint of an income category might be miscoded as below the FPL if their exact income falls above the FPL threshold (and vice versa for respondents with incomes below the midpoint of their income category). Because income is generally monotonically decreasing over the income ranges we observe, it is likely that there are more individuals whose income lies below the midpoint of the income category we use (and may thus be miscoded as above the FPL) (Congressional Research Service 2021). Therefore, it is likely that this measurement bias means we are underestimating the prevalence of poverty in our sample, though the magnitude of this bias is not observable. We also use an indicator variable for financial hardship, where respondents are asked whether it has been difficult for their household to pay for usual expenses in the past 7 days. Regarding public assistance receipt, participants in the HPS are also asked whether they or anyone in the household receives or has received food assistance benefits through the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) or a child tax credit in the past four weeks. Respondents are also asked about the source of their health insurance coverage, including Medicaid coverage for low-income families and individuals. Additionally, respondents were asked which of the following sources they and their household members used to meet their spending needs. They could choose multiple options including unemployment insurance (UI), stimulus payments, SNAP, school meal cards, and governmental rental assistance. This distinction between receipt and utilization of government services, both self-reported, is necessary to understand why discrepancies between the two can emerge.

4.2 Data quality and limitations

There are several limitations to the data from the HPS. First, about 18.8% of respondents did not provide a response to the household income question, which we use to determine poverty and FPL status.Footnote 4 This is common in surveys where participants are asked to provide information on their income (Bhat 1994). This study only uses complete cases and information for all analyses to avoid imputations for missing data. We report the distribution of educational attainment for respondents who reported their income and for those who did not in Appendix Fig. 1, which shows that our analytic sample (those who reported income) is positively selected on educational attainment relative to the non-respondents. This limits our ability to study these non-respondents, who may be accessing government services at higher rates than the rest of our sample, given their educational attainment. Several analyses have examined potential determinants of item non-response on population-based surveys and found that demographic and geographic characteristics like age, race, and region of residence are significantly associated with nonresponse to income and wealth questions while survey-specific characteristics like interviewer-interviewee concordance on socioeconomic status play a smaller role (Riphahn and Serfling 2005; Schenker et al. 2006). For employment and other socioeconomic outcomes, missingness rates were very low. Additionally, respondents to the income question report answers in ranges rather than exact amounts. We used the midpoint of each increment to measure individual-level household incomes. Another limitation of the data is that sexual identity is self-reported, raising the potential for response bias. Approximately 2% of adults in the Household Pulse Survey said that they did not know how to respond to the sexual orientation question. Nonresponse to self-identified sexual orientation questions is associated with race and ethnicity, so this feature of the data may indicate that we do not fully capture sexual minorities, especially people of color (Kim and Fredriksen-Goldsen 2013). Moreover, very little research has been able to measure misreported data. Our findings are likely biased towards the null since economically disadvantaged populations are most likely to misreport or skip the sexual orientation question.

In terms of limitations, other researchers have raised concerns about the representativeness of the HPS data, especially for estimating vaccine take-up and other COVID-19-related outcomes (Bradley et al. 2021). However, numerous analyses have used HPS data for timely health and socioeconomic research (Berkowitz and Basu 2021; Carpenter et al. 2022; Donnelly and Farina 2021). Moreover, we utilize survey weights provided by the U.S. Census Bureau to estimate nationally representative results. Finally, the core of our analysis examines relative receipt of government assistance programs, comparing gay men, lesbian women, and bisexual individuals to their heterosexual counterparts during the COVID-19 pandemic, rather than establishing pre-COVID baseline estimates for economic status and government assistance utilization.

Our data are all self-reported, and thus, there may be selection effects associated with disclosing sexual orientation in an online survey. Secondly, our sample of respondents only includes non-institutionalized adults randomly selected for participation in an email survey among US households. This means that we are missing homeless adults, adults residing in institutionalized medical and incarceration facilities, and individuals without email addresses. Some sexual minority research has suggested that these exclusions may disproportionately affect LGB individuals since they report higher rates of homelessness (Corliss et al. 2011; Durso and Gates 2012; Rosario et al. 2012), suggesting that our estimates on economic outcomes are likely a lower bound for the disparities experienced by sexual minorities. Finally, for most of the programs assessed, we can only measure public assistance take-up through self-reported utilization rather than actual receipt and utilization, limiting the scope of our analysis. Some sexual minorities may receive community-based and charitable assistance through health, housing, and other service-based centers. More broadly, it is difficult to determine how much of our results can be attributed to the economic shocks of COVID-19 and their disproportionate impacts on sexual minorities or to preexisting economic disparities between heterosexual and sexual minority populations. We do control for recent job loss in Appendix Table 3 to proxy for pandemic-related economic disruptions and find that our main results stand (higher take-up of public assistance), suggesting that our results are not entirely driven by pandemic-related economic phenomena.

4.3 Methods

We begin our analysis with estimating descriptive statistics. Then, to estimate the relative economic status of sexual minorities compared to their heterosexual peers, we utilize a regression approach with multiple specifications, following other literature on LGBTQ economic position and access to public assistance (Badgett et al. 2013; Badgett 2018; Carpenter et al. 2022). We specify estimation Eq. (1) in the following way:

where our outcome variables \({y}_{i}\) are economic outcomes (log household income, employment status, FPL status, and subjective financial hardship) for individual i and \({X}_{i}\) is a vector of individual characteristics. For all analyses, we stratify the sample by sex assigned at birth and control for indicator variables for gay men and lesbian women and bisexual individuals respectively. Due to this sex split, gay men and bisexual men are compared to heterosexual men while lesbian women and bisexual women are compared to heterosexual women. The coefficients of interest \({\beta }_{2}\) and \({\beta }_{3}\) represent the disparity in an economic outcome between gay/lesbian respondents and bisexual respondents, respectively, compared with heterosexual respondents.

Our preferred specification includes controls for the state of residence (\({\gamma }_{s}\)) and survey week (\({\delta }_{t}\)) to adjust for any state-specific or week-specific effects. Individual-level controls include age, age squared, race, ethnicity, relationship status, the presence of a child in the household, sex assigned at birth, gender minority status, the total number of children in the household, urban-rural status, and education (four categories).

To estimate public assistance receipt and utilization, we estimated a Heckman selection model:

where our outcome variables \({y}_{i}\) are various government assistance receipt and utilization outcomes for individual i and \({X}_{i}\) is a vector of individual characteristics. We use the same individual level controls. However, we also adjust for selection into poverty to differentiate between differentials based on needs or other factors. Hence, following Heckman selection methods, we estimate Eq. (3) using a probit model to obtain a correction term for this selection, and then adjust for this selection when estimating Eq. (2).

Finally, we restrict our sample to those below the federal poverty level and estimate Eq. (2) without the selection correction. In all regressions, we restrict our sample to complete cases. All regressions and descriptive statistics are weighted using HPS person weights computed by the U.S. Census Bureau in Stata version 16 (StataCorp 2019), except for the Heckman models.

4.4 Descriptive statistics

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for the full sample by sexual orientation and sex. Table 1 shows that gay men and lesbian women are younger, have fewer children, and are more likely to be employed than their heterosexual peers. Table 1 also shows that bisexual women are younger than gay men, lesbian women, and heterosexuals but are about as likely to have children as heterosexuals. Bisexual men also have lower incomes and lower likelihood of having children than heterosexuals. Additionally, bisexuals are more likely to have household incomes below the FPL than heterosexuals and gay/lesbian adults, especially bisexual women. These descriptive statistics display qualitatively similar patterns to those identified in other large population-based samples of LGB adults in the United States (Badgett et al. 2021).

Table 2 presents a demographic profile of self-identified LGB people with household incomes under the federal poverty level. In panel A, we estimate that approximately 90.0% of men below the FPL identified as heterosexual, 5.7% identified as gay, and 4.4% identified as bisexual. Among this subsample, heterosexual respondents were the oldest (46.1 years), followed by gay men (42.4 years), and bisexual men (34.9 years). In panel B, we estimate that approximately 88.7% of women below the FPL identified as heterosexual, 2.6% identified as gay or lesbian, and 8.7% identified as bisexual. Among women below the FPL, heterosexual respondents were the oldest (47.8 years), followed by lesbian women (37.3 years), and bisexual women (30.1 years). Heterosexual individuals experiencing poverty were more likely to be female than male (0.59 vs. 0.41). This pattern was even stronger among bisexual females and bisexual males (0.74 vs. 0.26). However, this sex breakdown is reversed for gay/lesbian adults experiencing poverty—they are more likely to be male than female (0.60 vs. 0.40). Motivated in part by this descriptive finding and prior literature that finds heterogenous economic outcomes for men and women among sexual orientation identity groups, we stratify our analyses by sex.

Gay/lesbian adults experiencing poverty were also less likely to be Black, non-Hispanic than heterosexuals (0.14 vs. 0.19). Bisexuals experiencing poverty were less likely to be Black, non-Hispanic (0.11 vs. 0.19), and more likely to be non-Hispanic White (0.58 vs. 0.49) than heterosexuals. Marriage rates among those experiencing poverty were much lower for gay men and lesbian women (0.15) and bisexuals (0.17) than for heterosexuals (0.32). Additionally, even among those with incomes below the federal poverty level, educational attainment was higher for gay men, lesbian women, and bisexuals than for heterosexual participants.

5 Results

Below, we present a collage of evidence on the economic status and government assistance utilization of self-identified LGB people. In general, we only present coefficients that are statistically significant at the 5% level, and otherwise, coefficients will be noted as suggestive (if significant at the 10% level) or nonsignificant. We began above by examining the demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of LGB and heterosexual people of all household incomes and then restricted to those who are below the FPL. Next, we use multivariable regression to examine the relative economic status of LGB adults compared to heterosexual adults, while controlling for demographic characteristics. Our regression models compare the receipt and utilization of government assistance for LGB respondents with heterosexual respondents in a full sample controlling for demographic characteristics and a restricted sample of respondents who are below the FPL. We conclude the section by examining the receipt and utilization of the expanded child tax credit for LGB people compared to heterosexual people.

5.1 Economic status of LGB individuals

Table 3 presents our regression estimates of Eq. (1) for four economic outcomes. It asks the question of whether gay men, lesbian women, and bisexuals adults experience different outcomes from heterosexual adults after controlling for observable characteristics. The format of Table 3 is as follows: each column is a different outcome with the same regression model with indicators for sexual orientation, and individual-level controls, as well as controls for state and survey week. Column (1) reports logged household income, calculated using interval regression; all other regressions were linear probability models. Column (2) reports employment; column (3) reports FPL status; and column (4) reports difficulty paying for expenses in the past week. We also provide the mean of each outcome below to contextualize the differences. The top panel estimates Eq. (1) for men, and the bottom panel displays the corresponding results for women.

The results in Table 3 indicate that bisexual men report 8.1% lower household incomes than otherwise comparable heterosexual respondents and that bisexual women report 8.9% lower household incomes than otherwise comparable heterosexual respondents. We also find suggestive evidence that lesbian women earn 3.2% less than otherwise comparable heterosexual women. In terms of poverty (column 3), we find that bisexual men are 2.2 percentage points more likely to report household incomes below the federal poverty level than heterosexual men. Relative to the mean of this outcome, poverty rates are 16% higher for bisexual men. Bisexual women are 2.9 percentage points more likely to report household income beneath the poverty line than heterosexual women (15% from the mean). Additionally, we find that bisexual men were approximately 6.1 percentage points more likely to report difficulty meeting expenses in the past week than otherwise comparable heterosexual respondents (24% relative to the mean); this differential was 6.0 percentage points for bisexual women (20% relative to mean). We also find a significant difference in self-reported financial hardship for gay men and lesbian women, despite not recording significant differences in other outcomes. Lesbian women were 4.6 percentage points more likely to report difficulty meeting expenses in the past week (15% relative to mean), while gay men were 3.4 percentage points more likely to do so (14% relative to mean). These results are broadly similar to what Chai and Maroto (2020) find, although we find statistically significant differences for gay men, as well as lesbian and bisexual women.

In Appendix Table 4, we analyze differences in economic outcomes with gay men and lesbian women as the comparison group to formally test for heterogeneity between sexual minority subgroups. We find that bisexual men earn 7.8% less than gay men and that bisexual women earn 5.7% less than lesbian women, highlighting the unique economic adversity faced by bisexual sexual minorities.

5.2 Receipt and utilization of government assistance

We next describe the results of estimating Eqs. (2) and (3), presented in Table 4. We estimate a two-step Heckman selection model, analyzing differences in receipt and utilization of public assistance programs while adjusting for selection into poverty status. This analysis examines whether gay men, lesbian women, and bisexual adults receive and use funds from public assistance programs at rates higher than those of otherwise comparable heterosexuals; all outcome regressions were linear probability models. The format of Table 3 is as follows: column (1) reports unemployment insurance utilization; column (2) reports stimulus check utilization; column (3) reports SNAP receipt; column (4) reports SNAP utilization; column (5) reports rental assistance utilization; and column (6) reports Medicaid coverage. We also provide the mean of each outcome below to contextualize the differences. The top panel estimates Eq. (2) for men, and the bottom panel displays the corresponding results for women. Additionally, within each panel, we show the coefficients from the poverty selection model for sexual identity.

The results in Table 4 indicate that bisexual men (10.2 pp), bisexual women (5.4 pp), gay men (6.9 pp), and lesbian women (2.9 pp) are more likely to receive SNAP benefits than their comparable heterosexual peers. Similar results are found for SNAP utilization. We also find that gay men are 2.4 percentage points, bisexual men are 4.2 percentage points, and bisexual women are 1.9 percentage points more likely to utilize rental assistance than otherwise comparable heterosexuals. Finally, we find that gay men (6.9 pp) are more likely to be insured by Medicaid than otherwise comparable heterosexual adults.

We note that use of the Heckman selection model in this setting should proceed with caution—identification using functional form arguments relies on correct specification of the selection equation, often empirically implausible. While it would be preferable to use an instrument or exclusion restriction to weaken those assumptions, our data are limited, and so we are unable to use an observed variable that affects poverty status but not public assistance receipt/utilization to overcome this identification challenge. We note that recent literature has highlighted the possibility of weaker identifying assumptions without an exclusion restriction in the selection context (Escanciano et al. 2016) and compare our corrected results with uncorrected results (reported in Appendix Table 6) to assess what we can learn from our analysis. Intuitively, because we observe elevated poverty rates for bisexual men and women (Table 3), we would expect the uncorrected estimate to be larger for these populations, and the Heckman correction to attenuate the coefficients. We see this qualitative pattern for several outcomes, including unemployment insurance utilization, stimulus check receipt, and Medicaid. However, for other outcomes, we observe larger coefficients in corrected models, suggesting a role for misspecification or other unobserved variables. Thus, these results should be interpreted with caution, though the similar qualitative patterns of results across uncorrected and corrected results increase our confidence in the broader pattern of results.

In addition, we assess the sensitivity of the uncorrected public assistance results (reported in Appendix Table 6) to differences in unobservable variables. Recently, methods to bound the impact of unobservable variables have been developed and applied to a wide range of problems in applied microeconomics (Oster 2019; Altonji et al. 2005). Typically, these methods consider coefficient and R2 stability as observable controls are added and use sensitivity parameters to assess the extent to which unobservable factors can account for the coefficient on a variable. In our context, we apply Oster’s (2019) estimator using Stata’s regsensitivity package and consider what amount of variation in the outcome unobservable variables would need to explain (relative to observable variables) for the coefficient on a dummy variable for gay/lesbian status or bisexual status to be equal to 0.

Appendix Table 7 reports the breakdown point (δ) for these methods with each of our main public assistance outcomes. We pool results rather than stratify by sex to gain precision. Observable variables are age, age squared, race, ethnicity, relationship status, the presence of a child in the household, sex, urban-rural status, gender minority status, the total number of children in the household, poverty status, and education (four categories), survey week, and state of residence. Unobservable variables would have to explain (δ × 100)% of the variation that these observables do for the coefficient on Gay/Lesbian or Bisexual to be 0. We assume the maximum attainable R2 if controlling for both observables and unobservables to be 1, which is almost certainly an upper bound, given the possibility of measurement error. Thus, these results should be considered lower bounds of the true breakdown points.

For some of our results, the breakdown points do not seem especially high—unobservables would have to explain 1.4% of the variation that observables do for the gay/lesbian differential takeup of unemployment insurance utilization to be 0 (unsurprising, given the coefficients are near zero and nonsignificant). For other outcomes, however, unobservables would have to explain a significant portion of the variation that our rich set of observables do, and for SNAP and Medicaid, even exceed the observables threshold. Thus, we believe these methods suggest that even in a worst-case scenario of unobservable selection that is not captured by standard controls or the Heckman model, there is still evidence of differential takeup for LGB populations.

In Appendix Table 5, we analyze differences in public assistance take-up with gay men and lesbian women as the comparison group to formally test for heterogeneity between sexual minority subgroups. Other than a 3.8 percentage point positive differential in Medicaid take-up for bisexual women, we do not find evidence of any consistent significant differences in public assistance take-up between gay men and bisexual men or lesbian women and bisexual women.

In Table 5, we examine regressions but restrict our sample to only those respondents who reported household incomes below the federal poverty level. We are estimating Eq. (1) using linear probability models. We find that gay men are 7.4 percentage points (22% relative to mean), and bisexuals are 7.2 percentage points (21% relative to mean) more likely to utilize SNAP than their heterosexual counterparts under the federal poverty line. Similar results are found for SNAP utilization, rental assistance, and Medicaid. We do not see comparable results for female sexual minorities below the federal poverty line—most estimates of differential utilization/receipt are close to zero and they are neither consistently positive nor negative.

5.3 Receipt and utilization of the child tax credit

Table 6 displays the results of estimating Eq. (2) for those programs that involve children in the household or at school. It is important to note that we control for both the presence of children in the household using an indicator variable and the number of children in the household (a continuous variable), though our results are statistically similar and larger in magnitude when dropping these controls. The format of Table 6 is as follows: the left panel estimates Eq. (2) for the full sample, while the right panel estimates Eq. (1) for the sample restricted to those below the FPL. Columns (1) and (3) report receipt of the child tax credit as the outcome, while columns (2) and (4) display the utilization of a school lunch card as the outcome.

The results in Table 6 indicate that gay men are 1.6 percentage points less likely to receive the child tax credit (10% relative to the mean) than otherwise comparable heterosexual men, even while controlling for the presence of children and number of children in the household. A similar difference is not reported for bisexual men. We also find that lesbian women are 3.7 percentage points less likely to receive the child tax credit and that bisexual women are 2.1 percentage points less likely to receive the child tax credit. This result holds when restricting to the below FPL sample; we find lesbian women experiencing poverty are 8.3 percentage points less likely to receive the child tax credit (27% relative to the mean) than otherwise comparable heterosexual women. Additionally, we find that bisexual women experiencing poverty are 3.5 percentage points less likely to receive the child tax credit (12% relative to the mean) than otherwise comparable heterosexual women. In Appendix Table 1, we present results that are robust to restricting our sample to individuals who have a child present in the household; even among only adults with children in the household, gay men, lesbian women, and bisexual women are significantly less likely to receive the child tax credit than their heterosexual counterparts.

6 Discussion

We used newly available data from a large, nationally representative sample of adults in the United States from the 2021–2022 U.S. Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey to study the economic outcomes and government assistance receipt and utilization of sexual minorities. Our regression models for economic outcomes, controlling for observable demographic characteristics, find that bisexual individuals have significantly lower household incomes, a higher likelihood of being below the federal poverty level, and higher self-reported financial hardship compared with otherwise similar heterosexual individuals. These results confirm previous literature that has found that bisexuals have worse economic outcomes than their heterosexual peers (Badgett et al. 2013, 2021).

Additionally, we find higher self-reported financial hardship for gay men and lesbian women, showing that the large literature on income differentials and economic status for gay/lesbian adults in the US also translates into higher levels of subjective economic distress (C. S. Carpenter 2005; Chai and Maroto 2020; Klawitter 2015). We also report higher poverty rates for bisexuals, supporting prior research in this area (Schneebaum and Badgett 2019; Uhrig 2015). Our results improve on the economic status of sexual minorities literature by using large samples of self-identified LGB individuals (rather than using partnership status to infer sexual orientation), including a subjective measure of economic status (i.e., self-reported financial hardship and receipt/utilization of public assistance programs), and leveraging new and recent data collected during the COVID-19 pandemic.

We find that lesbian women earn approximately 3.2 percentage points less than otherwise observationally similar heterosexual women (though marginally significant), contradicting most research pre-2015, which had found wage premia for lesbian women (Drydakis 2022; Klawitter 2015). However, several more recent studies have found significant lesbian wage penalties (Bryson 2017; Martell 2019). Several others have highlighted this puzzling case of a disappearing or waning lesbian wage premium during a time of improving social acceptance and propose that reduced family support as a result of intolerance of their sexual identity may be hurting lesbian women (Drydakis and Zimmermann 2020; Martell 2019). Additionally, it is possible that earlier studies, which often relied on using same-sex couple status or cohabitation as a proxy for sexual orientation, may have suffered from selection problems if same-sex couples are positively selected on income relative to the broader LGB population, including single LGB adults (Martell 2021). Because we use self-reported sexual identity, our results are less susceptible to this potential bias. Our findings confirm the empirical pattern of a lesbian wage penalty in a large, nationally representative survey of US adults during the COVID-19 pandemic and suggest that the emerging lesbian wage penalty may last.

Additionally, we find that LGB individuals utilize a range of government assistance programs at a higher rate than their heterosexual counterparts, even when allowing for selection into poverty status. These include SNAP and rental assistance for gay men, lesbian women, and bisexual individuals. This accords with prior work examining receipt of government assistance programs by sexual minorities, which has found higher rates of take-up for SNAP, TANF, and Medicaid (Badgett et al. 2013; Badgett 2018; Brown et al. 2016). We add to the literature by evaluating several programs that have not, to our knowledge, been examined in the context of differential take-up for sexual minorities, including unemployment insurance, stimulus payments, and rental assistance. We show that these results are robust to adjusting for selection into poverty status. Additionally, we demonstrate that when restricting to a low-income subsample, we continue to see differentials for gay and bisexual men, but not for lesbian and bisexual women. We find the largest differentials in rental assistance programs and unemployment insurance.

These generally higher rates of participation and utilization of government assistance programs among LGB people accord with the qualitative predictions we generate from the take-up literature. That the effects are more robust for gay and bisexual men suggests that social networks may play a significant role. As to which of the explanations we propose may explain the differentials, we cannot fully adjudicate, but there are several signs that some explanations are less plausible than others. For example, the take-up differentials are robust to controlling for educational attainment, suggesting that higher educational attainment is not the only mechanism that explains differential take-up of public assistance programs. Additionally, they are robust to controlling for recent job loss (see Appendix Table 3), suggesting that differential exposure to employment shocks from the COVID-19 pandemic do not fully explain the differentials we observe. This suggests that some combination of lessened stigma, fewer alternatives for financial support (low substitutability), and social network effects may be responsible for higher take-up of public assistance among sexual minorities.

We also find that gay men, lesbian women, and bisexual women are less likely to receive the advance child tax credit, an enhanced policy that has been promoted during the pandemic for its major impact on child poverty reduction (Corinth et al. 2021; Goldin and Michelmore 2022). We found statistically significant disparities between sexual minorities and their heterosexual peers even when controlling for the presence of a child in the household, the total number of children in the household, or restricting to only households with children present. Additionally, the difference appears even among the subsample below the FPL. One potential explanation would be an asymmetry between how LGB individuals report a child in the household for the Household Pulse Survey and whether the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) recognizes that child for the eligibility determination used to establish recipients of the child tax credit. For example, if an LGB individual (or couple) was supporting an adolescent whose parents did not accept their sexual orientation or gender identity, they might report that child as “in their household” for the HPS, but the IRS would not recognize that relationship unless the child was legally adopted. These instances of informal family networks and “found family” are much more common among LGB individuals than among straight individuals (Jackson Levin et al. 2020; McConnell et al. 2015; Snapp et al. 2015). Unfortunately, we are unable to pinpoint specific mechanisms, but we encourage future studies to explore these important issues.

There are several limitations to our analysis. One is that we use self-reported survey data, which may lead to biased reporting of outcomes, especially of government assistance receipt (Celhay et al. 2022; Meyer et al. 2022). Due to a scarcity of ways to identify sexual minorities, the use of administrative data to confirm our findings is not currently possible, although as more surveys and datasets collect sexual minority status, future work could use this data and administrative linkages to analyze if these public assistance differentials are also observed in administrative data. Additionally, our inability to fully adjudicate between the different explanations for the observed differentials is a major limitation. While we generate qualitative predictions guided by prior work in the program participation literature and examine which of these is supported by the HPS data, ideally, future work could instrument for each potential explanation using exogenous variation in the variable of interest (e.g., social networks) and examine whether disparities are explained by this exogenous variation. Finally, we use data from the COVID-19 pandemic, given that it is the only data source that allows us to study these differentials with sufficient power. However, as we discussed in Section 4.2, it is possible that the results we find are driven by the effects of the pandemic rather than pre-existing differences in outcomes. Future work can use data from other time periods to determine whether our results are observed outside the pandemic context.

We also derive several findings that may be of interest to policymakers. Estimating the take-up of public assistance programs is vital for modelling their microeconomic and macroeconomic impacts, as nearly all will have some degree of nonparticipation. Our analysis shows that one demographic group, LGB individuals, take up public assistance programs at higher rates than economically similar heterosexual individuals, and that this disparity is likely due to a combination of social network effects, lessened stigma, and increased reliance on public programs. Policymakers should consider how these factors were differentially established by the LGB community and whether there are policy or community actions (like utilizing social and peer networks to target public assistance) that may streamline public program participation for populations in greatest need. Additionally, policymakers may consider public policies that directly target LGB people (e.g., same-sex marriage) may consider our estimates of higher public program take-up; private benefits (e.g., health insurance) may crowd out public benefits when sexual minorities enjoy protections in employment, housing, and education. Finally, the disparities in receipt of the child tax credit for LGB people who have children point to an area where policymakers must examine whether current targeting and disbursement methods are not fully reaching LGB individuals who may be eligible for the program.

In addition, our limitations highlight the need for better data on LGBTQ populations and serve as a call to policymakers and administrators to incorporate instruments that measure sexual orientation and gender identity into survey and administrative data sources. Better data would allow for us to observe administrative rather than self-reported receipt of public assistance, offer a more complete picture of economic outcomes, and expand the set of data sources available to study the economic well-being of this population outside the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

7 Conclusion

Our findings confirm that bisexuals experience poorer economic outcomes and that gay men, lesbian women, and bisexuals take up government assistance programs at higher rates than their heterosexual counterparts in the U.S. context. Additionally, we find evidence that this pattern of higher take-up among gay and bisexual men is maintained in a low-income subsample, not explained by selection into poverty, and is likely due to a combination of social network effects, lessened stigma, and increased reliance on public programs. Finally, we find that gay men, lesbian women, and bisexual women are less likely to receive the recently enhanced child tax credit than similarly situated heterosexuals. In so doing, our study adds to a growing literature on the experiences of LGB people in poverty. Our results further the call for more social science and policy research on the inequality and poverty experienced in sexual minority communities.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available on the U.S. Census Bureau website, https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/household-pulse-survey/datasets.html.

Notes

Irrespective of these reasons, it is important to study the outcomes and economic well-being of marginalized populations regardless of group size or demographic characteristics, as LGB populations have historically been neglected in the economics literature (though the quantity of research has grown significantly) (Badgett 1995; Badgett et al. 2021).

However, this could be misleading if there is differential take-up even conditioning on economic status.

We exclude respondents whose sex assigned at birth was allocated by the HPS hot-decking procedure.

This rate is lower among gay men and lesbian women (14.2%) and bisexuals (17.4%) than heterosexuals (19.1%). This may suggest that our estimates are an upper bound of economic disparities, as respondents missing income data likely had worse economic outcomes.

References

Ahmed AM, Hammarstedt M (2010) Sexual orientation and earnings: a register data-based approach to identify homosexuals. J Popul Econ 23(3):835–849. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-009-0265-4

AIDS Project LA (2022) Mission and strategic plan. https://aplahealth.org/about/mission-strategic-plan/. Accessed 22 June 2023

Aizer A, Currie J (2004) Networks or neighborhoods? Correlations in the use of publicly-funded maternity care in California. J Public Econ 88(12):2573–2585. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2003.09.003

Albelda R, Schneebaum A, Badgett MVL, Gates G (2009) Poverty in the lesbian, gay, and bisexual community. The Williams Institute at UCLA School of Law. https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep35577

Allen H, Wright BJ, Harding K, Broffman L (2014) The role of stigma in access to health care for the poor. Milbank Q 92(2):289–318. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0009.12059

Altonji J, Elder T, Taber C (2005) Selection on observed and unobserved variables: assessing the effectiveness of Catholic schools. J Polit Econ. https://doi.org/10.1086/426036

Alvira-Hammond M, Gennetian LA (2015) How hispanic parents perceive their need and eligibility for public assistance. Bethesda, MD: National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families

Badgett MVL (1995) The wage effects of sexual orientation discrimination. ILR Rev 48(4):726–739. https://doi.org/10.1177/001979399504800408

Badgett MVL (2018) Left out? Lesbian, gay, and bisexual poverty in the U.S. Popul Res Policy Rev 37(5):667–702. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-018-9457-5

Badgett MVL, Sears RB, Ho D (2006) Supporting families, saving funds: an economic analysis of equality for same-sex couples in New Jersey. Rutgers J Law Public Policy 4:1 (Fall 2006)

Badgett MVL, Carpenter CS, Sansone D (2021) LGBTQ economics. J Econ Perspect 35(2):141–170. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.35.2.141

Badgett M, Durso LE, Schneebaum A (2013) New Patterns of Poverty in the Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Community. Retrieved from https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8dq9d947

Bansak C, Starr M (2021) Covid-19 shocks to education supply: how 200,000 U.S. households dealt with the sudden shift to distance learning. Rev Econ Househ 19(1):63–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-020-09540-9

Berkowitz SA, Basu S (2021) Unmet social needs and worse mental health after expiration of COVID-19 federal pandemic unemployment compensation. Health Aff 40(3):426–434. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.01990

Bertrand M, Luttmer EFP, Mullainathan S (2000) Network effects and welfare cultures*. Quart J Econ 115(3):1019–1055. https://doi.org/10.1162/003355300554971

Bhat CR (1994) Imputing a continuous income variable from grouped and missing income observations. Econ Lett 46(4):311–319. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-1765(94)90151-1

Bitler M, Hoynes H, Schanzenbach DW (2020) The Social Safety Net in the Wake of COVID-19. https://doi.org/10.3386/w27796

Black DA, Sanders SG, Taylor LJ (2007) The economics of lesbian and gay families. J Econ Perspect 21(2):53–70

Borjas GJ, Hilton L (1996) Immigration and the welfare state: immigrant participation in means-tested entitlement programs. Q J Econ 111(2):575–604. https://doi.org/10.2307/2946688

Bradley VC, Kuriwaki S, Isakov M, Sejdinovic D, Meng X-L, Flaxman S (2021) Unrepresentative big surveys significantly overestimated US vaccine uptake. Nature 600(7890):695–700. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-04198-4

Brady D (2005) The welfare state and relative poverty in rich Western Democracies, 1967–1997. Soc Forces 83(4):1329–1364. https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.2005.0056

Breder K, Bockting W (2022) Social networks of LGBT older adults: an integrative review. Psychol Sex Orientat Gend Divers. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000552

Brewster KL, Tillman KH, Jokinen-Gordon H (2014) Demographic characteristics of lesbian parents in the United States. Popul Res Policy Rev 33(4):503–526. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-013-9296-3

Brown TNT, Romero AP, Gates GJ (2016) Food insecurity and SNAP participation in the LGBT community. The Williams Institute, July(July), pp 1–28.

Bryson A (2017) Pay equity after the Equality Act 2010: does sexual orientation still matter? Work Employ Soc 31(3):483–500. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017016664678

Carpenter CS (2005) Self-reported sexual orientation and earnings: evidence from California. Ind Labor Relat Rev 58(2):258–273. https://doi.org/10.1177/001979390505800205

Carpenter C, Gates GJ (2008) Gay and lesbian partnership: evidence from California. Demography 45(3):573–590. https://doi.org/10.1353/dem.0.0014

Carpenter CS, Sansone D (2021) Cigarette taxes and smoking among sexual minority adults. J Health Econ 79(26692):1–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2021.102492

Carpenter CS, Gonzales G, McKay T, Sansone D (2021) Effects of the affordable care act dependent coverage mandate on health insurance coverage for individuals in same-sex couples. Demography 58(5):1897–1929. https://doi.org/10.1215/00703370-9429469

Carpenter CS, Lee MJ, Nettuno L (2022) Economic outcomes for transgender people and other gender minorities in the United States: first estimates from a nationally representative sample. South Econ J. https://doi.org/10.1002/soej.12594

Celhay PA, Meyer BD, Mittag N (2022) What leads to measurement errors? Evidence from reports of program participation in three surveys. http://www.nber.org/papers/w29652. Accessed 22 June 2023

Chai L, Maroto M (2020) Economic insecurity among gay and bisexual men: evidence from the 1991–2016 U.S. General Social Survey. Sociol Perspect 63(1):50–68. https://doi.org/10.1177/0731121419849100

Colledge L, Hickson F, Reid D, Weatherburn P (2015) Poorer mental health in UK bisexual women than lesbians: evidence from the UK 2007 Stonewall Women’s Health Survey. J Public Health 37(3):427–437. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdu105

Congressional Research Service (2021) The U.S. income distribution: Trends and issues. https://crsreports.congress.gov. Accessed 22 June 2023

Corinth K, Meyer B, Stadnicki M, Wu D (2021) The Anti-Poverty, Targeting, and Labor Supply Effects of the Proposed Child Tax Credit Expansion.https://doi.org/10.3386/w29366

Corliss HL, Goodenow CS, Nichols L, Bryn Austin S (2011) High burden of homelessness among sexual-minority adolescents: findings from a representative massachusetts high school sample. Am J Public Health 101(9):1683–1689. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2011.300155

Creamer J, Shrider EA, Burns K, Chen F (2022) Poverty in the United States: 2021. US Census Bureau

Currie J (2004) The Take Up of Social Benefits.https://doi.org/10.3386/W10488

Dempsey D, Parkinson S, Andrews C, McNair R (2020) Family relationships and LGB first homelessness in Australia: what do we know and where should we go? J Sociol 56(4):516–534. https://doi.org/10.1177/1440783320927087

DiBennardo R, Gates GJ (2014) Research note: US Census Same-Sex Couple Data: adjustments to reduce measurement error and empirical implications. Popul Res Policy Rev 33(4):603–614. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-013-9289-2

DiMaggio P, Garip F (2012) Network effects and social inequality. Ann Rev Sociol 38(1):93–118. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.012809.102545

Donnelly R, Farina MP (2021) How do state policies shape experiences of household income shocks and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic? Soc Sci Med 269:113557. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113557

Drydakis N (2022) Sexual orientation and earnings: a meta-analysis 2012–2020. J Popul Econ 35(2):409–440. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-021-00862-1

Drydakis N, Zimmermann KF (2020) Guest editorial. Int J Manpow 41(6):621–628. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJM-03-2020-481

Durso LE, Gates GJ (2012) Serving our youth: Findings from a national survey of services providers working with lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender youth who are homeless or at risk of becoming homeless. UCLA: The Williams Institute. Retrieved from https://escholarship.org/uc/item/80x75033

Edelman M (1992) Understanding the gay and lesbian vote in ’92. Public Perspect 4:32–33

Elton E, Gonzales G (2022) Health insurance coverage and access to care by sexual orientation and marital/cohabitation status: new evidence from the 2015–2018 National Health Interview Survey. Popul Res Policy Rev 41(2):479–493. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-021-09670-7

Escanciano JC, Jacho-Chavez D, Lewbel A (2016) Identification and estimation of semiparametric two-step models. Quant Econ. https://doi.org/10.3982/QE328

Everett BG, Mollborn S (2014) Examining sexual orientation disparities in unmet medical needs among men and women. Popul Res Policy Rev 33(4):553–577. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-013-9282-9

Feinstein BA, Dyar C (2017) Bisexuality, minority stress, and health. Curr Sex Health Rep 9(1):42–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11930-017-0096-3

Finkelstein A, Hendren N (2020) Welfare analysis meets causal inference. J Econ Perspect 34(4):146–167. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.34.4.146

Fothergill A (2003) The stigma of charity: gender, class, and disaster assistance. Sociol Q 44(4):659–680. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1533-8525.2003.tb00530.x

Garner TI, Safir A, Schild J (2020) Changes in consumer behaviors and financial well-being during the coronavirus pandemic: results from the U.S. household pulse survey. Monthly Lab Rev 143(12):1–21

Goldin J, Michelmore K (2022) Who benefits from the child tax credit? Nat Tax J 000–000. https://doi.org/10.1086/717919

Gonzales G, Blewett LA (2014) National and state-specific health insurance disparities for adults in same-sex relationships. Am J Public Health 104(2):95–105

Gonzales G, de Mola EL (2021) Potential COVID-19 vulnerabilities in employment and healthcare access by sexual orientation. Ann LGBTQ Public Popul Health 2(2):87–103. https://doi.org/10.1891/LGBTQ-2020-0052

Gonzales G, Deal C (2022) Health risk factors and outcomes among gender minority high school students in 15 US states. JAMA 327(15):1498. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2022.3087

Han J, Meyer BD, Sullivan JX (2020) Income and poverty in the COVID-19 pandemic. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity Summer 2020 Special Edition, pp 85–118

Herek GM, Norton AT, Allen TJ, Sims CL (2010) Demographic, psychological, and social characteristics of self-identified lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in a US probability sample. Sex Res Soc Policy 7(3):176–200. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-010-0017-y

Hoffman SD, Maynard RA (eds) (2008) Kids having kids: Economic costs & social consequences of teen pregnancy. The Urban Insitute

Horsfall ST (2012) Social problems: An advocate group approach (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429493102

Hussey LS (2011) Is welfare pro-life? Assistance programs, abortion, and the moderating role of states. Soc Serv Rev 85(1):75–107

Jackson Levin N, Kattari SK, Piellusch EK, Watson E (2020) “We Just Take Care of Each Other”: Navigating ‘chosen family’ in the context of health, illness, and the mutual provision of care amongst queer and transgender young adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(19):7346. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17197346

Jones PE (2021) Political distinctiveness and diversity among Lgbt Americans. Public Opin Q. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfab030

Keith-Jennings B, Llobrera J, Dean S (2019) Links of the supplemental nutrition assistance program with food insecurity, poverty, and health: evidence and potential. Am J Public Health 109(12):1636–1640. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2019.305325

Kim HJ, Fredriksen-Goldsen KI (2013) Nonresponse to a question on self-identified sexual orientation in a public health survey and its relationship to race and ethnicity. Am J Public Health 103(1):67–69

Klawitter M (2015) Meta-analysis of the effects of sexual orientation on earnings. Ind Relat: J Econ Soc 54(1):4–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/irel.12075

Ko W, Moffitt RA (2022) Take-up of Social Benefitshttps://doi.org/10.3386/W30148

Leppel K (2007) Home-ownership among opposite- and same-sex couples in the US. Fem Econ 13(1):1–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/13545700601075070

Lewis GB, Rogers MA, Sherrill K (2011) Lesbian, gay, and bisexual voters in the 2000 U.S. Presidential Election [Article]. Polit Policy 39(5):655–677. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-1346.2011.00315.x

Mann S, Blackaby D, O’Leary N (2019) Sexual identity and wellbeing: a distributional analysis. Econ Lett 181:133–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2019.04.023

Manski CF (1993) Identification of endogenous social effects: the reflection problem. Rev Econ Stud 60(3):531. https://doi.org/10.2307/2298123

Marcén M, Morales M (2022) The effect of same-sex marriage legalization on interstate migration in the USA. J Popul Econ 35(2):441–469. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-021-00842-5

Martell ME (2019) Age and the new lesbian earnings penalty. Int J Manpow 41(6):649–670. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJM-10-2018-0322

Martell ME (2021) Labor market differentials estimated with researcher-inferred and self-identified sexual orientation. Econ Lett 205:109959. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2021.109959

Martell ME, Roncolato L (2023) Economic vulnerability of sexual minorities: Evidence from the US Household Pulse Survey. Popul Res Policy Rev 42(2):28

McConnell EA, Birkett MA, Mustanski B (2015) Typologies of social support and associations with mental health outcomes among LGBT youth. LGBT Health 2(1):55–61. https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2014.0051

Meyer BD, Mittag N, Goerge RM (2022) Errors in survey reporting and imputation and their effects on estimates of food stamp program participation. J Hum Resour 57(5):1605–1644. https://doi.org/10.3368/jhr.58.1.0818-9704R2

Moffitt R (1983) An economic model of welfare stigma. Am Econ Rev 73(5):1023–1035

Morin R, Taylor P, Patten E (2012) A bipartisan nation of beneficiaries. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2012/12/18/a-bipartisan-nation-of-beneficiaries/. Accessed 22 June 2023

Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (2022) Poverty guidelines. https://aspe.hhs.gov/topics/poverty-economic-mobility/poverty-guidelines. Accessed 22 June 2023

Oster E (2019) Unobservable selection and coefficient stability: Theory and evidence. J Bus Econ Stat. https://doi.org/10.1080/07350015.2016.1227711

Patacchini E, Ragusa G, Zenou Y (2015) Unexplored dimensions of discrimination in Europe: homosexuality and physical appearance. J Popul Econ 28(4):1045–1073. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-014-0533-9

Perales F, Huang Y (2020) Parental financial transfers: do they vary by children’s sexual orientation? Soc Forces 98(4):1465–1497. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/soz111

Plug E, Berkhout P (2004) Effects of sexual preferences on earnings in the Netherlands. J Popul Econ 17(1):117–131. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-003-0136-3

Riphahn RT, Serfling O (2005) Item non-response on income and wealth questions. Empir Econ 30(2):521–538. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-005-0247-7

Rosario M, Schrimshaw EW, Hunter J (2012) Risk factors for homelessness among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths: a developmental milestone approach. Child Youth Serv Rev 34(1):186–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2011.09.016

Schenker N, Raghunathan TE, Chiu P-L, Makuc DM, Zhang G, Cohen AJ (2006) Multiple imputation of missing income data in the National Health Interview Survey. J Am Stat Assoc 101(475):924–933. https://doi.org/10.1198/016214505000001375

Schneebaum A, Badgett MVL (2019) Poverty in US lesbian and gay couple households. Fem Econ 25(1):1–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2018.1441533

Sherkat DE, de Vries KM, Creek S (2010) Race, religion, and opposition to same-sex marriage [Article]. Soc Sci Q 91(1):80–98. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6237.2010.00682.x

Smith RA, Haider-Markel DP (2002) Gay and lesbian Americans and political participation: A reference handbook. Bloomsbury Publishing USA