Abstract

Purpose

Antidepressants are frequently prescribed to older people with depression but little is known on predictors of discontinuation in this population. We, therefore, investigated factors associated with early discontinuation of antidepressants in older adults with new diagnoses or symptoms of depression in English primary care.

Methods

Data from a nationally representative cohort of patients aged 55 and over were used to evaluate the association between discontinuation of antidepressant medication after a single prescription and potential explanatory variables, including socio-demographic factors, polypharmacy and age-related problems such as dementia.

Results

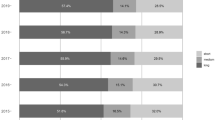

Overall, during the study period we observed 34,715 new courses of antidepressant treatment initiated after recorded symptoms or diagnoses of depression. Antidepressant discontinuation after a single prescription was more common in people with depressive symptoms (32%) than in those with diagnosed depression (21.6%). In those diagnosed with depression and in women with depressive symptoms we found that, after adjusting for confounders, the odds of early discontinuation significantly increased after age 65 with a peak at around age 80 and then either levelled or reduced thereafter. Early discontinuation was also significantly less common in people with dementia and in those with diagnosed depression living in more rural areas.

Conclusions

Early discontinuation of antidepressants increases in the post-retirement years and is higher in those with no formal diagnosis of depression, those without dementia and those with diagnosed depression living in urban areas. Alternative treatment strategies, such as non-drug therapies, or more active patient follow-up should be further considered in these circumstances.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Arroll B, Elley CR, Fishman T, Goodyear-Smith FA, Kenealy T, Blashki G, Kerse N, Macgillivray S (2009) Antidepressants versus placebo for depression in primary care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 3:CD007954

Kok RM, Nolen WA, Heeren TJ (2012) Efficacy of treatment in older depressed patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of double-blind randomized controlled trials with antidepressants. J Affect Disord 141:103–115

Health and Social Care Information Centre (2016) Prescriptions dispensed in the community 2005–2015. http://digital.nhs.uk/catalogue/PUB20664. Accessed 25 Jan 2019

Walters K, Falcaro M, Freemantle N, King M, Ben-Shlomo Y (2018) Sociodemographic inequalities in the management of depression in adults aged 55 and over: an analysis of English primary care data. Psychol Med 48(9):1504–1513

Luppa M, Sikorski C, Luck T, Ehreke L, Konnopka A, Wiese B, Weyerer S, Konig HH, Riedel-Heller SG (2012) Age- and gender-specific prevalence of depression in latest-life—systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 136(3):212–221

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (2009) Depression in adults: recognition and management (updated in April 2018). https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg90. Accessed 25 Jan 2019

van Geffen EC, Gardarsdottir H, van Hulten R, van Dijk L, Egberts AC, Heerdink ER (2009) Initiation of antidepressant therapy: do patients follow the GP’s prescription? Br J Gen Pract 59(559):81–87

Hunot VM, Horne R, Leese MN, Churchill RC (2007) A cohort study of adherence to antidepressants in primary care: the influence of antidepressant concerns and treatment preferences. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry 9(2):91–99

Demyttenaere K, Enzlin P, Dewe W, Boulanger B, De Bie J, De Troyer W, Mesters P (2001) Compliance with antidepressants in a primary care setting, 1: beyond lack of efficacy and adverse events. J Clin Psychiatry 62:30–33

Hansen DG, Vach W, Rosholm JU, Sondergaard J, Gram LF, Kragstrup J (2004) Early discontinuation of antidepressants in general practice: association with patient and prescriber characteristics. Fam Pract 21(6):623–629

Burton C, Anderson N, Wilde K, Simpson CR (2012) Factors associated with duration of new antidepressant treatment: analysis of a large primary care database. Br J Gen Pract 62(595):e104–e112

Booth N (1994) What are the read codes? Health Libr Rev 11(3):177–182

Horsfall L, Walters K, Petersen I (2013) Identifying periods of acceptable computer usage in primary care research databases. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 22(1):64–69

Department for Communities and Local Government (2011) The English indices of deprivation 2010. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/english-indices-of-deprivation-2010. Accessed 25 Jan 2019

Davé S, Petersen I (2009) Creating medical and drug code lists to identify cases in primary care databases. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 18(8):704–707

Lewis JD, Bilker WB, Weinstein RB, Strom BL (2005) The relationship between time since registration and measured incidence rates in the general practice research database. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 14(7):443–451

Joint Formulary Committee (2013) British national formulary, 66th edn. BMJ Group and Pharmaceutical Press, London

Brilleman SL, Salisbury C (2013) Comparing measures of multimorbidity to predict outcomes in primary care: a cross sectional study. Fam Pract 30(2):172–178

Zeger SL, Liang KY, Albert PS (1988) Models for longitudinal data—a generalized estimating equation approach. Biometrics 44(4):1049–1060

Huber PJ (1967) The behaviour of maximum likelihood estimators under non-standard conditions. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 5th Berkeley symposium on mathematical statistics and probability, Berkeley, USA

Royall RM (1986) Model robust confidence intervals using maximum likelihood estimators. Int Stat Rev 54:221–226

Akaike H (1974) A new look at statistical model identification. IEEE Trans Autom Contr AC -19:716–723

Schwarz G (1978) Estimating the dimension of a model. Ann Stat 6(2):461–464

Pan W (2001) Akaike’s information criterion in generalized estimating equations. Biometrics 57:120–125

Durrleman S, Simon R (1989) Flexible regression models with cubic splines. Stat Med 8(5):551–561

Harrell FE (2001) Regression modeling strategies: with applications to linear models, logistic and ordinal regression, and survival analysis. Springer, New York

StataCorp (2015) Stata statistical software: release 14. StataCorp LP, College Station

Seeman E, Compston J, Adachi J, Brandi ML, Cooper C, Dawson-Hughes B, Jonsson B, Pols H, Cramer JA (2007) Non-compliance: the Achilles’ heel of anti-fracture efficacy. Osteoporos Int 18(6):711–719

Briesacher BA, Andrade SE, Fouayzi H, Chan KA (2008) Comparison of drug adherence rates among patients with seven different medical conditions. Pharmacotherapy 28(4):437–443

Aikens JE, Nease DE Jr, Klinkman MS (2008) Explaining patients’ beliefs about the necessity and harmfulness of antidepressants. Ann Fam Med 6(1):23–29

Deaville JA, Jones LM (2003) Health-care challenges in rural areas: physical and sociocultural barriers. Prof Nurse 18(5):262–264

Burroughs H, Lovell K, Morley M, Baldwin R, Burns A, Chew-Graham C (2006) ‘Justifiable depression’: how primary care professionals and patients view late-life depression? A qualitative study. Fam Pract 23(3):369–377

Gum AM, Arean PA, Hunkeler E, Tang L, Katon W, Hitchcock P, Steffens DC, Dickens J, Unutzer J (2006) Depression treatment preferences in older primary care patients. Gerontologist 46(1):14–22

Blak BT, Thompson M, Dattani H, Bourke A (2011) Generalisability of The Health Improvement Network (THIN) database: demographics, chronic disease prevalence and mortality rates. Inform Prim Care 19(4):251–255

Mitchell AJ, Vaze A, Rao S (2009) Clinical diagnosis of depression in primary care: a meta-analysis. Lancet 374:609–619

van Geffen EC, van Hulten R, Bouvy ML, Egberts AC, Heerdink ER (2008) Characteristics and reasons associated with nonacceptance of selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitor treatment. Ann Pharmacother 42(2):218–225

Burton C, Cochran AJ, Cameron IM (2015) Restarting antidepressant treatment following early discontinuation—a primary care database study. Fam Pract 32(5):520–524

Funding

This paper presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) School for Public Health Research (SPHR-10043). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. The NIHR SPHR is a partnership between the Universities of Sheffield; Bristol; Cambridge; Imperial; and University College London; The London School for Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM); LiLaC—a collaboration between the Universities of Liverpool and Lancaster; and Fuse—The Centre for Translational Research in Public Health a collaboration between Newcastle, Durham, Northumbria, Sunderland and Teesside Universities.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical statement

Use of THIN for scientific research was approved by the NHS South East Multi-Centre Research Ethics Committee in 2003. Scientific approval to undertake this study was obtained from IQVIA World Publications Scientific Review Committee (SRC) in November 2014 (SRC reference number: 14-068).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Falcaro, M., Ben-Shlomo, Y., King, M. et al. Factors associated with discontinuation of antidepressant treatment after a single prescription among patients aged 55 or over: evidence from English primary care. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 54, 1545–1553 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-019-01678-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-019-01678-x