Abstract

Background

This systematic review aimed to describe the outcomes of the most severely injured polytrauma patients and identify the consistent Injury Severity Score based definition of utilised for their definition. This could provide a global standard for trauma system benchmarking.

Methods

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist was applied to this review. We searched Medline, Embase, Cochrane Reviews, CINAHL, CENTRAL from inception until July 2022. Case reports were excluded. Studies in all languages that reported the outcomes of adult and paediatric patients with an ISS 40 and above were included. Abstracts were screened by two authors and ties adjudicated by the senior author.

Results

7500 abstracts were screened after excluding 13 duplicates. 56 Full texts were reviewed and 37 were excluded. Reported ISS groups varied widely between the years 1986 and 2022. ISS groups reported ranged from 40–75 up to 51–75. Mortality varied between 27 and 100%. The numbers of patients in the highest ISS group ranged between 15 and 1451.

Conclusions

There are very few critically injured patients reported during the last 48 years. The most critically injured polytrauma patients still have at least a 50% risk of death. There is no consistent inclusion and exclusion criteria for this high-risk cohort. The current approach to reporting is not suitable for monitoring the epidemiology and outcomes of the critically injured polytrauma patients.

Level of evidence

Level 4—systematic review of level 4 studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Trauma is a disease from energy transfer to the organism [1]. Above a certain threshold of energy deposition, the human body is unable to dissipate energy rapidly enough and physical injury results. The spectrum of injury runs from trivial superficial injuries to unsurvivable complete destruction of the body. Major trauma remains a persistent threat to life and function [2]. Advances in injury prevention and trauma care throughout the twentieth century, and particularly the last 20 years, have reduced the risk of dying from injury in most of the high-income countries of the world [3]. To further study and benchmark, trauma surgeons have sought to classify trauma patients by severity to measure performance and allow comparison between systems [4]. Classification and benchmarking systems must use common thresholds and cutoffs to allow comparison between centres and time periods.

For practical reasons, groups compared are limited by a minimum injury severity above which they are referred to as major trauma or severely injured. To allow fair comparison, this threshold requires a standardized scoring system that is valid across continents and populations. The most frequently used anatomical scoring system, the Injury Severity Score (ISS) is derived from the Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS) [5]. The AIS a highly detailed scoring system developed to describe and rank injury severity (from 1 to 6) across the human body [6]. The AIS requires skilled data coders but as a purely anatomic system allows quality assurance and in-hours coding from the medical record. The ISS is a scale from 1 to 75 and is derived from the sum of the squares of the three highest AIS body regions [5]. The most commonly used ISS threshold is ≥ 16 [7]. This threshold is the inflection point between ISS 14 and 16 where trauma mortality began to exceed 10%. Below this the risk of death falls while also including the increasingly large numbers of less severely injured patients. Even above ISS ≥ 16 the distribution of severity of injuries is skewed towards the mild end of the spectrum of disease. For example in the New South Wales (Australia) Trauma Registry, 62% of patients have an ISS < 25 and 96% of patients have an ISS < 41 [8]. An increase in the proportion of patients with lower injury severity, or an expansion of the definition of major trauma to include less severely injured patients would further dilute the influence that the most severely injured patients would have on summary statistics used to characterize and compare the outcomes and performance of major trauma care. If the threshold for ‘major trauma’ is expanded to ISS ≥ 13, the inclusion of these additional low ISS patients further dilutes the high ISS patients. An expansion of the definition of major trauma to this level would expand the proportion of patients with an ISS of < 25–72% and those having an ISS of < 41–97%.

In its original description, the ISS was not categorized into groups. There are a variety of injury severity thresholds initially proposed at geometric nexuses in the calculation of the ISS from its basis in AIS. Debate exists surrounds the floor threshold defining injury severity given variability in some AIS injury classification updates with proposals to reduce the floor to ISS > 12 [9]. ISS subgroups were first proposed in the initial description of ISS noting that “scores below 10 rarely die” [5]. ISS 50–75 was first described as a group in 1988 [10]. In 1990, the Major Trauma Outcome Study, a pivotal study in the development of measurement and risk adjustment of trauma mortality, referred to ISS 50–74 and separated ISS 75 [11]. ISS 50–75 has been used intermittently and with no standardized term terminology, variably and perhaps accidentally including ISS 48 due to discrepancies between > and ≥ . In 1999, ISS 50–75 was still referred to as patients with “fatal injuries” despite its patients having a mortality of approximately 50% [12]. In 2015 a major binational study confirmed it as a repeatable, useful ‘most severely injured’ population balancing patient numbers with comparable mortality from the triplets of included injuries across multiple nations [13].

Beyond mortality, the outcomes of the ISS 50–75 group remain unknown. It is also unknown whether the improvements in trauma mortality over time have improved the mortality in the most severely injured, ISS 50–75 group or whether this remains stubbornly high [14]. No major trauma registry currently benchmarks functional outcomes between centres [15].

The systematic review aimed to describe the outcomes of the most severely injured polytrauma patients and demonstrate the possible incomplete and varied application of injury severity subgroups at the most severely injured end of the spectrum of major trauma.

Methods

Selection criteria and search strategy

Studies were included if they used a floor ISS threshold of 40 or above and measured outcomes of mortality. Medline, Embase, Cochrane Reviews, CINAHL, CENTRAL were searched using a variety of search terms including “’ISS, ‘injury severity’, ‘died’, ‘mortality’, ‘outcome’, ‘severe’” (SDC1). Published studies up to July 2022 were included.

Study selection, and inclusion and exclusion criteria

Review and extraction were conducted in Covidence (Covidence systematic review software, Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia. Available at www.covidence.org). All abstracts were reviewed by two reviewers with ties broken by the senior author. Studies were included if they summarized the outcome of patients after major injury. All full texts were reviewed by the first author and senior author, and ties resolved by consensus. Studies were excluded if there was no separation of patients into ISS categories, if the maximum ISS category was not ≥ 40, or the study was duplicated. Data was extracted by the first author and summarized in table form.

Study quality and risk of bias

Studies’ inclusion and exclusion criteria were captured and are presented to the reader. The PRISMA 2020 checklist was used when designing and drafting the manuscript [16] (SDC 2).

Results

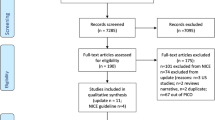

Up to July 2022, 7,513 studies were identified with 13 duplicates, leaving 7500 studies. All abstracts were reviewed and 56 identified for full text screening. 37 were excluded, primarily due to no separation of patients into ISS categories (Fig. 1). 19 studies were included for final extraction [12, 13, 17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33] (Fig. 1, Table 1).

Groups used and study types

The minimum threshold for inclusion in the ‘most severe’ group was not consistent and included ≥ 40, > 41, ≥ 46, ≥ 48, ≥ 50, 50–59, > 50, and ≥ 60. Some studies relied on prospective registry collection with the rest retrospective. There were two studies with predefined aims and prospective collection. Most studies’ aims were epidemiological. One study sought to measure the effect of prehospital treatment. Others tested change over time either in before-and-after or year-on-year designs during the development of trauma care systems. One study compared outcomes of patients treated in trauma-centres with against those treated in non-trauma centres.

Study quality

There was variable reporting of population, inclusion, and exclusion criteria. Few studies reported exclusion of prehospital death and no studies reported the use of autopsy to inform ISS score generation in prehospital deaths.

Outcomes

Mortality of ‘most severe’ groups with an ‘all-comers’ inclusion criteria ranged from 27% [18] to 91% [19] (Fig. 2).

Discussion

Our systematic review demonstrates the limited and incomplete use of a ‘most severely injured’ group in trauma outcome reporting. A variety of high ISS cutoffs have been used in the literature. Most are used without citation or justification. Rozenfeld et al. demonstrated that 50–75 is the most functional high ISS group and remains the largest series to date [13]. Russel et al. demonstrated the considerable variability in mortality rate of component AIS triplets at the same ISS level at most levels below an ISS of 50, advancing its use over lower cutoffs such as ≥ 40 as is used in the NSW Trauma Registry [8, 29, 34].

Our review is strong in that it had no limitations in calendar year or language and use a broad search criterion with manual review of 7,500 titles and abstracts. It is weakened by the lack of standardized reporting language around high ISS groups.

In conclusion, there is considerable variation in the definition and reporting of the ‘most severe’ group of trauma patients. The outcomes of these patients are uncertain but include at least a 50% risk of death. Authors should standardize on ISS50-75 given its large, well validated measure of the most severely injured [13]. Major registries should adopt the ISS50-75 group as a public performance measure to educate other authors in its standardization. International consensus efforts regarding high ISS groups should standardize on language to reduce the burden of search regarding high ISS groups such as ISS > XX or ISSXX-YY (ISS > 48, ISS ≥ 50, ISS50-75). Editors could continue to encourage authors to standardize terms used to describe injury severity groups within polytraumatized patients.

References

Balogh ZJ. Polytrauma: it is a disease. Injury. 2022;53(6):1727–9.

Ahmad FB, Anderson RN. The leading causes of death in the US for 2020. JAMA. 2021;325(18):1829–30.

Wong TH, Lumsdaine W, Hardy BM, Lee K, Balogh ZJ. The impact of specialist trauma service on major trauma mortality. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;74(3):780–4.

Optimal hospital resources for care of the seriously injured. Bull Am Coll Surg. 1976;61(9):15–22.

Baker SP, O’Neill B, Haddon W Jr, Long WB. The injury severity score: a method for describing patients with multiple injuries and evaluating emergency care. J Trauma. 1974;14(3):187–96.

MacKenzie EJ, Shapiro S, Eastham JN. The Abbreviated Injury Scale and Injury Severity Score. Levels of inter- and intrarater reliability. Med Care. 1985;23(6):823–35.

Boyd CR, Tolson MA, Copes WS. Evaluating trauma care: the TRISS method. Trauma Score and the Injury Severity Score. J Trauma. 1987;27(4):370–8.

Institute of Trauma and Injury Management. Major Trauma in NSW:2019–2020. 2021. https://aci.health.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/629114/ACI-1274-Major-Trauma-in-NSW-2019-20-V1.1.pdf

Palmer CS, Gabbe BJ, Cameron PA. Defining major trauma using the 2008 Abbreviated Injury Scale. Injury. 2016;47(1):109–15.

Copes WS, Champion HR, Sacco WJ, Lawnick MM, Keast SL, Bain LW. The injury severity score revisited. J Trauma. 1988;28(1):69–77.

Champion HR, Copes WS, Sacco WJ, Lawnick MM, Keast SL, Bain LW Jr, et al. The Major Trauma Outcome Study: establishing national norms for trauma care. J Trauma. 1990;30(11):1356–65.

Sampalis JS, Denis R, Lavoie A, Frechette P, Boukas S, Nikolis A, et al. Trauma care regionalization: a process-outcome evaluation. J Trauma. 1999;46(4):565–79 (discussion 79-81).

Rozenfeld M, Radomislensky I, Freedman L, Givon A, Novikov I, Peleg K. ISS groups: are we speaking the same language? Inj Prev. 2014;20(5):330–5.

Hardy BM, Enninghorst N, King KL, Balogh ZJ. The most critically injured polytrauma patient mortality: should it be a measurement of trauma system performance? Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00068-022-02073-z.

TraumaRegister DGU. 20 years TraumaRegister DGU((R)): development, aims and structure. Injury. 2014;45(Suppl 3):S6–13.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. PLoS Med. 2021;18(3): e1003583.

Bagher A, Andersson L, Wingren CJ, Ottosson A, Wangefjord S, Acosta S. Outcome after red trauma alarm at an urban Swedish hospital: implications for prevention. Scand J Public Health. 2015;43(5):506–13.

Ball CG, Das D, Roberts DJ, Vis C, Kirkpatrick AW, Kortbeek JB. The evolution of trauma surgery at a high-volume Canadian centre: implications for public health, prevention, clinical care, education and recruitment. Can J Surg. 2015;58(1):19–23.

Burdett-Smith P, Airey M, Franks A. Improvements in trauma survival in leeds. Injury. 1995;26(7):455–8.

Cameron PA, Fitzgerald MC, Curtis K, McKie E, Gabbe B, Earnest A, et al. Over view of major traumatic injury in Australia-implications for trauma system design. Injury. 2020;51(1):114–21.

Candefjord S, Asker L, Caragounis EC. Mortality of trauma patients treated at trauma centers compared to non-trauma centers in Sweden: a retrospective study. Eur. 2020;27:27.

Covarrubias J, Grigorian A, Nahmias J, Chin TL, Schubl S, Joe V, et al. Vices-paradox in trauma: positive alcohol and drug screens associated with decreased mortality. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108866.

Duvall DB, Zhu X, Elliott AC, Wolf SE, Rhodes RL, Paulk ME, et al. Injury severity and comorbidities alone do not predict futility of care after geriatric trauma. J Palliat Med. 2015;18(3):246–50.

Fatovich DM, Jacobs IG, Langford SA, Phillips M. The effect of age, severity, and mechanism of injury on risk of death from major trauma in Western Australia. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;74(2):647–51.

Jamulitrat S, Sangkerd P, Thongpiyapoom S, Na NM. A comparison of mortality predictive abilities between NISS and ISS in trauma patients. J Med Assoc Thai. 2001;84(10):1416–21.

Kaweski SM, Sise MJ, Virgilio RW. The effect of prehospital fluids on survival in trauma patients. J Trauma. 1990;30(10):1215–9.

Kuhne CA, Ruchholtz S, Kaiser GM, Nast-Kolb D. Mortality in severely injured elderly trauma patients–when does age become a risk factor? World J Surg. 2005;29(11):1476–82.

Mann SM, Banaszek D, Lajkosz K, Brogly SB, Stanojev SM, Evans C, et al. High-energy trauma patients with pelvic fractures: management trends in Ontario, Canada. Injury. 2018;49(10):1830–40.

Russell R, Halcomb E, Caldwell E, Sugrue M. Differences in mortality predictions between Injury Severity Score triplets: a significant flaw. J Trauma. 2004;56(6):1321–4.

Sampalis JS, Boukas S, Nikolis A, Lavoie A. Preventable death classification: interrater reliability and comparison with ISS-based survival probability estimates. Accid Anal Prev. 1995;27(2):199–206.

van der Sluis CK, Klasen HJ, Eisma WH, ten Duis HJ. Major trauma in young and old: what is the difference? J Trauma. 1996;40(1):78–82.

Vyhnanek F, Fric M, Pazout J, Waldauf P, Ocadlik M, Dzupa V. Present concept for management of severely injured patients in Trauma Centre Faculty Hospital Kralovske Vinohrady. Cas Lek Cesk. 2012;151(10):468–71.

Wurm S, Rose M, von Ruden C, Woltmann A, Buhren V. Severe polytrauma with an ISS ≥ 50. Z Orthop Unfall. 2012;150(3):296–301.

Institute of Trauma and Injury Management. Major Trauma in NSW:2018–19. 2020. https://aci.health.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0018/601092/Major-Trauma-in-NSW_-2018-19.-A-Report-from-the-NSW-Trauma-Registry-final.pdf.

Funding

There was no specific funding for this project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors whose names appear on the submission: (1) made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data; or the creation of new software used in the work; (2) drafted the work or revised it critically for important intellectual content; (3) approved the version to be published; and (4) agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The review did not require ethics approval.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hardy, B.M., Varghese, A., Adams, M.J. et al. The outcomes of the most severe polytrauma patients: a systematic review of the use of high ISS cutoffs for performance measurement. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00068-023-02409-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00068-023-02409-3