Abstract

Background

Hemorrhagic shock is the second leading cause of death in blunt trauma and a significant cause of mortality in non-trauma patients. The increased use of resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA) as a bridge to definitive control for massive hemorrhage has provided promising results in the trauma population. We describe an extension of this procedure to our hemodynamically unstable non-trauma patients.

Methods

This is a retrospective review of patients requiring REBOA for end stage non-traumatic abdominal hemorrhage from our tertiary care facility. After excluding patients with trauma, supradiaphragmatic bleed and thoracic/abdominal aortic aneurysms, demographics, etiology of bleed, REBOA placement specifics, complications and outcomes were reviewed.

Results

From August 2013 to August 2016, 11 patients were identified requiring REBOA placement for hemodynamic instability from non-traumatic abdominal hemorrhage. Average patient age was 54.9 (SD 15.2). Sixty-four percent suffered cardiac arrest prior to REBOA, with mean shock index of 1.29. Average time from diagnosis of shock (MAP ≤ 65) or signs of bleeding to placement of REBOA was 177 min. The leading etiologies of hemorrhage were ruptured visceral aneurysm and massive upper gastrointestinal bleed. REBOA was placed by both acute care and vascular surgeons. The procedure was mainly completed in the operating room in 82% of the patients and at the bedside in 18%. One patient expired before operative repair. Definitive surgical control of the source of bleeding was obtained by open surgical approach (n = 6) and combined surgical and endovascular approach (n = 4). In-hospital survival was 64%. There were no local complications related to REBOA placement.

Conclusion

Similar to the trauma population, REBOA is an adjunctive technique for proximal control of bleeding as well as resuscitation in end stage non-traumatic intra-abdominal hemorrhage. We propose an algorithmic approach to REBOA use in this population and a larger prospective review is necessary to determine both the timing of REBOA placement and which non-traumatic patients may benefit from this technique.

Level of evidence

V.

Study type

Brief report.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Non-compressible torso hemorrhage (NCTH) is the leading cause of preventable death in trauma, vascular, and acute care surgery requiring open surgery or angiographic embolization [1]. Successful treatment of hemorrhage in these populations require early diagnosis and treatment [2]. Historically, for trauma patients in extremis or cardiac arrest from NCTH, inflow control was obtained through a resuscitative thoracotomy with aortic cross clamping until definitive exploration and repair was performed. Resuscitative Endovascular Balloon Occlusion of the Aorta (REBOA), has reemerged in the literature to aid in proximal hemorrhage control for patients with traumatic injury. This bridge to definitive therapy in trauma patients has sparked an interest in the treatment of non-traumatic hemorrhage.

Balloon occlusion was first described in 1950 during the Korean War, where a balloon was placed intravascularly in three patients, temporizing two until laparotomy, however, no patients survived [3]. Endovascular techniques advanced in the non-trauma population with Greenber and Malina demonstrating favorable outcomes with the use of distal thoracic aortic balloon occlusion for temporary control in ruptured aortic aneurysm [4, 5]. From that literature, new interest arose for balloon occlusion as a temporary bridge to definitive hemostasis, while supporting myocardial and cerebral perfusion. Through animal models in hemorrhagic shock, REBOA, as compared to resuscitative thoracotomy with aortic cross clamp, has shown similar carotid blood flow, decreased acidosis and decreased vasopressor requirements [6, 7,].

While REBOA usage has increased significantly in the last several years in traumatic injury for proximal hemorrhage control in NCTH, limited data are available for its use in emergency general surgery. Case reports have been previously described of use of REBOA in post-partum hemorrhage, gastrointestinal bleed and necrotizing pancreatitis [1, 8, 9]. We describe the outcomes from our single center case series of 11 patients with placement of REBOA for end-stage non-traumatic NCTH and propose an algorithm to guide the use of REBOA in this population.

Methods

Institutional review board approval was obtained. Patients undergoing REBOA placement from August 1, 2013 to August 1, 2016, at a large tertiary referral center, were identified and records reviewed. All patients had REBOA placed by either trained acute care surgeons or vascular surgeons for non-traumatic causes of abdominal or pelvic hemorrhage leading to refractory shock or cardiac arrest. Patients with traumatic etiology, esophageal varices, or known thoracic/abdominal aneurysms were excluded from the study.

Patient demographics and clinical variables were collected. Indications for the index operations were recorded from attending surgeon. Preoperative variables were collected from the index operation including shock index (heart rate/systolic blood pressure), shock (defined as vasopressor support required to maintain mean arterial pressure > 65 mmHg), or cardiac arrest (defined as cessation of cardiopulmonary activity requiring ACLS protocol). End stage hemorrhage was defined as partial responders or non-responders to ongoing blood transfusions. Time of diagnosis was defined as times from first MAP < 65 or signs of hemodynamic instability, cardiac arrest or bleeding.

Intraoperative variables for the index operation were retrospectively collected. Location of placement of the REBOA, size of REBOA sheath, approach for placement and location of balloon were all noted. Standard aortic zones were used with zone 1 placement being in the descending thoracic aorta, distal to the left subclavian and proximal to the celiac axis and zone 3 placement between the renal arteries and the aortic bifurcation. Time from diagnosis of shock to placement of REBOA was extrapolated from anesthesia and nursing records. Intraoperative and postoperative packed red cell administration from the time period was collected. The type of definitive repair was extracted from operative notes.

Discharge disposition and in-hospital mortality were recorded. Local complications secondary to REBOA placement as well as systemic complications were documented.

Continuous variables are presented as mean with standard deviation. Categorical variables are presented as mean and percentage or median and interquartile range.

Results

Eleven patients were identified that had a REBOA placed emergently for non-traumatic abdominal and pelvic hemorrhage. Median age of group was 55 years (42–68). Men comprised 73% of the patients. 64% experienced cardiac arrest. All patients were in refractory shock at time of the procedure, with mean shock index of 1.29. The underlying pathology in this cohort included ruptured visceral aneurysm (27%), gastrointestinal bleed (27%) hemorrhagic necrotizing pancreatitis (18%), iatrogenic liver laceration (9%) renal artery bleed (9%) and right iliac artery hemorrhage (9%) (Table 1).

In 82% of the patients REBOA was placed in the operating room. Average time to REBOA placement from time of diagnosis was 177 min (± 175). 72% of REBOAs were placed percutaneously. 91% of REBOA deployments were in Zone 1. For hemorrhage control of the precipitating event, 54% patients underwent open repair, whereas 36% underwent a hybrid (open and endovascular) procedure (Table 2). Two patients expired prior to formal operation with one patient expiring prior to operation and another patient did not tolerate balloon deflation. The median intraoperative transfusion requirement was 15 (7–30) units of PRBC.

Post-operatively, 27% required additional abdominal exploration for ongoing bleeding. There were no local complications attributable to REBOA placement. Systemic complications, such as acute kidney injury (AKI), pneumonia and bowel ischemia, occurred in 6/11 patients, with no noted myocardial infarctions or pulmonary embolisms noted (Table 3). The etiology of the bowel ischemia was thought to be due to a delayed stent complication, unrelated to REBOA.

Median hospital length of stay was 13 (3–23) days, with median ICU stay of 6 (3–10.5) days with 5 (2–6.5) days on ventilator. Mortality at index hospitalization was 36%, with only one mortality attributed to uncontrolled hemorrhage (Table 3).

Discussion

This series describes a subset of non-trauma patients in the most severe stages of hemorrhagic shock with 64% of patients in cardiac arrest. While all the patients were in end stage hemorrhagic shock, their underlying etiologies were highly variable. With the small sample size, we are unable to draw any definitive conclusions about any potential advantage or disadvantage related to the procedure. No directly attributable REBOA related complications were noted in this group confirming, similarly to its use in trauma, that this emergent procedure it can be performed safely by appropriately trained surgeons, regardless of specialty.

There are significant differences between both the type and location of bleeding, as well as underlying patient characteristics when comparing this patient set to those in studies involving traumatic hemorrhage. First, patients in this study have a wide range of etiologies leading hemorrhage, markedly different than the trauma patient. The variance in time to placement maybe due to a delayed realization of hemorrhagic etiology of shock as well as other attempts and methods to stabilize a hypotensive non-trauma patient. Blood transfusions, fluid resuscitation, as well as vasopressor administration all can lead to an increase in time from initial hypotension, “stabilizing” the patient for a period of time, until they become “unstable” requiring more invasive action and REBOA placement.

Location of REBOA placement was noted to mostly be in the operating room. At the start of this study, the equipment was not readily available in the Emergency Department, and the Intensive Care Unit. Supplies were kept in the operating room as well as the Trauma Receiving Unit (a separate entity from our emergency department). Since then, REBOA kits have been added to all of these areas. These non-trauma patients seem to hemorrhage differently than trauma patients. In trauma, the bleeding typically is large volume and abrupt into the peritoneal cavity. While this same type of bleeding can be found in non-trauma patients, typically these type of bleeds are slower in nature or into more confined spaces. Bleeding in the non-trauma population can typically be supported with resuscitation and vasopressors, to a degree, before hemodynamic collapse. Peri-operative placement was performed prior to laparotomy in all cases (whether this was in the ED or OR), as it provided hemodynamic stabilization prior to incision with the associated release of any support from abdominal tamponade. Additionally, balloon occlusion was used as a means for proximal control in challenging intraoperative hemorrhage in already unstable patients, as seen in hemorrhagic pancreatitis and ruptured viscera, which made up almost half the cohort. Difficult definitive control was evident as 36% of our population received a combination of open and endovascular techniques.

Our patient population in the non-trauma arm is also significantly older than those included in the traumatic REBOA series with an average age of 54.9, almost 15 years older than in the AAST trial [10]. With advanced age, there are likely more underlying patient comorbidities, and less tolerance to both hemorrhage and aortic occlusion. Severe peripheral vascular disease may be higher in this population; however, we did not find this to limit access or placement of the sheath or balloons or increase local complications in our small series.

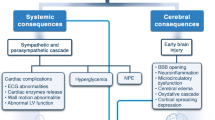

Another important note is that only one of these non-trauma REBOAs was placed in zone 3. Outside of obstetrical hemorrhage or known pelvic disease, the opportunities for utilization in the pelvis are limited. In cardiac arrest from bleeding, zone 1 inflation is recommended, both for proximal vascular occlusion as well as to increase myocardial and cerebral perfusion and attempts to have return of spontaneous circulation. This is a double edged sword as zone 1 inflation has significant physiologic implications. Most importantly, zone 1 occlusion is tolerated for a limited time due to visceral ischemia and physiologic effects. One patient in the series did not survive balloon deflation despite adequate hemorrhage control, underlying the importance of a prompt definitive hemostasis and restoration of normal arterial flow. We have created an algorithm implemented at our institution for non-traumatic hemorrhage (Fig. 1). Our algorithm considers that REBOA has two separate and distinct physiologic purposes, both proximal hemorrhage control and assistance with resuscitation, depending on the patient’s underlying etiology and current physiologic parameters.

Very few non-traumatic disease processes are contraindications for REBOA placement in the setting of exsanguination, except bleeding must be below the level of the diaphragm. Ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms is another disease process better dealt with through image guided wires and balloon occlusion, not the algorithmic-based approach below. Known aortic aneurysms are associated with tortuosity of the access vessels as well as difficult maneuverability of blindly placed wires/balloons to coil in the sac, therefore, these should also be considered separately.

We also noted that with our final three patients, the 7F catheter was used. The time from initial hypotension to successful placement of the device decreased. This is likely twofold. First, with increased experience with the REBOA procedure, providers were quicker to respond with placement when the patient was a transient or non-responder to blood product administration and the lower profile sheath likely hastened the placement by the provider, due to less perceived complications from the smaller diameter.

Conclusion

The above report is our institutions experience with REBOA placement for non-trauma hemorrhage by a trained group of vascular and acute care surgeons. Due to our small sample size, few conclusions can be drawn about its effect on outcomes; however, this small cohort does suggest that REBOA placement can be performed safely without complications in this population. Differences in patient age, comorbidities, a high incidence of concomitant acute illness, also contribute to a difference between the two clinical scenarios. We propose the algorithm as appropriate guideline for use in this group until further data can be collected and analyzed regarding appropriate utilization of REBOA in this challenging patient population.

Availability of data and material

Available on request.

References

Morrison JJ, Galgon RE, Jansen JO, Cannon JW, Rasmussen TE, Eliason JL. A systematic review of the use of resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta in the management of hemorrhagic shock. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016;80(2):324–34.

Qasim Z, Brenner M, Menaker J, Scalea T. Resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta. Resuscitation. 2015;96:275–9.

Hughes CW. Use of an intra-aortic balloon catheter tamponade for controlling intra-abdominal hemorrhage in man. Surgery. 1954;36(1):65–8.

Greenberg RK, Srivastava SD, Ouriel K, et al. An endoluminal method of hemorrhage control and repair of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms. J Endovasc Ther. 2000;7(1):1–7.

Malina M, Veith F, Ivancev K, Sonesson B. Balloon occlusion of the aorta during endovascular repair of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Endovasc Ther. 2005;12(5):556–9.

Spence PA, Lust RM, Chitwood WR, Iida H, Sun YS, Austin EH. Transfemoral balloon aortic occlusion during open cardiopulmonary resuscitation improves myocardial and cerebral blood flow. J Surg Res. 1990;49(3):217–21.

Sesma J, Labandeira J, Sara MJ, Espila JL, Artech A, Saez MJ. Effect of intra-aortic balloon in external thoracic compressions during CPR in pigs. Am J Emerg Med. 2002;20(5):453–62.

Sano H, Tsurukiri J, Hoshiai A, Oomura T, Tanaka Y, Ohta S. Resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta for uncontrollable nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. World J Emerg Surg 2016;11:20.

Tsurukiri J, Akamine I, Sato T, Sakurai M, Okumura E, Moriya M, et al. Resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta for uncontrolled hemorrhagic shock as an adjunct to hemostatic procedures in the acute care setting. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2016;24:13.

Dubose JJ, Scalea TM, Brenner M, Skiada D, Inaba K, Cannon J, et al. The AAST prospective aortic occlusion for resuscitation in trauma and acute care surgery (AORTA) registry: data on contemporary utilization and outcomes of aortic occlusion and resuscitative balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA). J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016;81(3):409–19.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MRH: writing, literature search, and data analysis. NH: data collection and literature search. AMP: data collection, writing and critical revision. MB: writing and critical revision. SC: data collection and analysis. JDP: writing and critical revision. JJD: critical revision. TS: critical revision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Melanie R Hoehn, Natasha Hansraj, Amelia M Pasley, Samantha Cox, Jason D Pasley, Jose J Diaz and Thomas Scalea declare they have no conflict of interest. Megan Brenner is on the Clinical Advisory Board of Prytime Medical Inc.

Human and animal rights

Retrospective chart review without human or animal involvement.

Informed consent

No informed consent performed as retrospective chart review.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hoehn, M.R., Hansraj, N.Z., Pasley, A.M. et al. Resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta for non-traumatic intra-abdominal hemorrhage. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 45, 713–718 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00068-018-0973-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00068-018-0973-0