Abstract

Objectives

The aims of this audit were twofold: (1) to demonstrate the contribution of the auditing process in evaluating the success of child and adolescent health policy in Slovenia between 2012 and 2019, and (2) to expand on the commentary published in the International Journal of Public Health in 2019 to demonstrate the benefits of auditing in improving public health policy in general.

Methods

The audit followed health, safety and environmental approaches as per the standards of public health policy.

Results

Due to poor intersectoral coordination and weak associations between environmental and health indicators, no clear evidence could be established that child and adolescent health policy contributed to positive changes in child and adolescent health from 2012 to 2019.

Conclusions

Auditing should become an essential component of measuring the success of public health policies. Attention should also be paid to the following issues affecting youth health: sleeping and eating habits, economic migration, poverty, etc.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In a piece of 2019 commentary published in the International Journal of Public Health, ‘Auditing in addition to compliance monitoring: a way to improve public health’, authors stressed that the actual effects of public health policy on society is determined by the quality of its implementation (Bizjak and Kontić 2019). They further argued a key condition for ensuring health policies’ successful implementation: an active system of responsible and competent authorities capable of prioritizing issues, assigning responsibilities and effectively distributing the available budget. Such a system invariably entails continuous monitoring to evaluate the success of implemented measures, assess the extent to which goals are achieved and identify barriers in attempted policy improvements. In terms of monitoring policy implementation, there are some caveats regarding limited information about its performance (Kaur 2010; Usmanova and Mokdad 2013; van den Driessen Mareeuw et al. 2015; Donkor et al. 2018; Gulis 2019). In this context, the European Commission recently stressed the importance of learning from assessments of existing air quality legislation in view of regularly updating public health policy (The Green Deal; European Commission 2019). However, despite general recognition that auditing is beneficial, few studies focus on the effectiveness of public health or health services (Kingdon 1995; Brownson et al. 2010; Shankar et al. 2011; Singh 2014; Bradley et al. 2016; Bernet et al. 2018).

To demonstrate that auditing is an effective tool in identifying possibilities to improve public health in Slovenia, an agreement was made in 2019 between national public health professionals and an auditing team to check the performance of the national strategy on children and adolescent health related to environmental quality for the period 2012–2020 (referred to as the Strategy, the Government of the Republic of Slovenia 2011; see summary below). This Strategy was selected for the following characteristics: (1) it is a national level policy; (2) it builds on international efforts and policies regarding health and environmental initiatives [World Health Organisation (WHO), United Nations Environment Programme, United Nations Development Programme, European Environment Agency, European Food and Safety Agency, etc.]; (3) it is accompanied by a specific action plan to implement the Strategy (referred to as the action plan (AP); Government of the Republic of Slovenia 2015), which details priority goals, related activities, monitoring indicators, etc.; and (4) there is an intergovernmental working group (IWG) that has been established to follow the implementation of the Strategy and regularly report its findings to the government. The audit lasted from September 2019 to April 2020 with an open end for a post-audit phase. This was occasioned by the changed priorities triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic. The scope and foci of the audit are depicted in Table 1.

Summary of the strategy

By signing the Parma Declaration in 2010 (WHO Regional Office for Europe 2010), the Republic of Slovenia has committed itself to protecting adolescent health against harmful environmental factors, acknowledging it as an integral part of the country’s public health and environmental policies. Other important backgrounds of the Strategy are the European Environment and Health Strategy (EC 2003), European Environment and Health Action Plan 2004–2010 (EC 2004) and the 6th Environment Action Programme of the European Community 2002–2012 (EC 2011).

On 29 July 2010, the Slovenian government appointed the IWG to implement the commitments of the Strategy. The IWG’s first task was preparing the Adolescent Environmental Health Action Programme and the Chemical Safety Action Programme, which were merged to form the Strategy.

The Strategy determined four general priority goals: (1) ensuring population health by improving access to safe drinking water and appropriate municipal wastewater management, (2) reducing injury and obesity through safe environments and healthy diet paired with physical activity, respectively, (3) preventing disease by improving indoor and outdoor air quality and (4) preventing diseases caused by chemical, biological and physical risk factors. The AP further specified the activities leading to the achievement of goals, the duration of said activities, monitoring indicators and the institutions responsible. Specific areas of focus were also determined, such as youth participation, climate change, inequality, new technology and excessively polluted areas.

The WHO/ENHIS indicators, combined with those developed by the National Institute of Public Health (NIJZ) and Slovenian Environment Agency, were applied in the context of monitoring the effects of Strategy implementation. The initial set included regulatory aspects of environmental protection, air pollution in cities, drinking water quality, infant mortality due to respiratory disease, asthma and allergic diseases in children, child exposure to polluted air—PM10 particles, waterborne disease outbreaks (epidemics), access to safe drinking water, etc. The indicators had to be updated regularly to properly capture new and additional views on the relationships between exposure to environmental risk factors and observed health outcomes. Some additional health indicators were obesity, diabetes, congenital irregularities, etc. Annual surveys and reporting of adolescent health status according to these indicators were to be provided by the NIJZ.

The Strategy defined that the IWG will report to the Government every 2 years on the Strategy’s implementation progress, the findings of which would be used to plan future health and environmental policy.

Methods

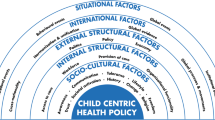

The key aspects and principles of auditing were applied according to the definitions and guidance offered by Cahill et al. (1987), INTOSAI (2004), CCPS (2011) and ECA (2017). Adaptations to the area of public health policy followed the experience of Brownson et al. (2010), Shankar et al. (2011) and Bernet et al. (2018). Figure 1 shows the main elements of an established audit programme. Standard auditing tools, such as questionnaires, worksheets, guidelines, etc. were used to collect, sort, analyse and retrieve audit information.

The audit was based on reviewing the Strategy’s AP and the annual reporting of environmental quality and related health status from 2012 to 2019, provided by the NIJZ. Interviewing the personnel engaged in Slovenian public health policy preparation, primarily from the Ministry of Health, the NIJZ and the Ministry of the Environment and Spatial Planning, was performed to verify specific policy information in the reviewed documents in the context of intersectoral coordination. The head of the IWG was also consulted regarding its work.

In the pre-audit phase, three meetings were held with experts from the three institutions engaged in preparing the Strategy. At these meetings, which were also associated with work on the European Union-funded project on the Health and Environment Research Agenda (HERA: https://www.heraresearcheu.eu/) for Europe, the selection of documents for review were discussed and approved. Since the initially selected documentation covered practically all components of environmental and public health issues, the audit team decided to narrow the scope and perform the audit only for the Strategy documents. The key reasons for this relate to the characteristics of the Strategy as described in the introduction in items (1) through (4).

The evaluation was conducted to compare the health status of children and adolescents before and after the Strategy’s implementation. The attempt was to assign (positive) changes to the Strategy and related AP activities. Key metrics were based on associations between selected health and environmental indicators, and trends in the observed period were to be analysed. The overall policy evaluation included the following topics: design and consistency between the Strategy and AP, implementation monitoring, outcome variables (i.e. the performance of the activities and their results: qualitative, qualitative or both), transparency and reporting and availability of data for evaluation. Some indicators were quantitative (e.g. share of monitored drinking water and measured air quality parameters), while others required combined quantitative and qualitative metrics (e.g. determining if and to what extent municipalities follow public health guidelines). The evaluation categories, applied in Tables 2 and 3, were:

-

G—Good performance of the activity (complete and quality), results documented and auditable

-

W—Weak performance of the activity, results unclear/non-transparent or poorly documented

-

O—Not observed or evaluated. Available information was not complete enough for thorough evaluation

-

X—Not applicable: evaluation based on selected indicators is not applicable (sensible)

-

Y—Consistent: full overall or specific consistency between the Strategy and AP

-

N—Not consistent: Strategy and AP are not consistent

-

P—Partial consistency between the Strategy and AP

Discussion

Limited healthcare resources and related issues make evaluating the impact of public health interventions increasingly important (Mays and Smith 2011; Méndez and Osorio 2017; Bernet et al. 2018; Saeed et al. 2019). The need for more child and adolescent health research was emphasised in relation to the child and adolescent health strategy development (Dratva et al. 2018). The auditing of the Strategy and its AP provided a framework to encourage and facilitate continuous evaluation of the effectiveness of activities with a specific focus on the health of children and adolescents in relation to the environment. The activities of the AP were both preventive and curative and concerned environmental quality. Regarding adolescent health, however, they were strictly preventive, with no evidence for necessary interventions prior to the implementation of the Strategy. In this context, the AP activities aimed at improving environmental quality can yield a positive long-term health impact. The Strategy and AP are not fully consistent; the Strategy’s time span is from 2012 to 2020, but the AP’s activity plans cover 2015–2020. The AP includes some additional topics and activities, but it does not include some topics identified as important by the Strategy. It also fails to include some of the Strategy’s specific areas of interest, e.g. youth participation, new technology, etc.

Policy effectiveness (e.g. measured by expenditures, investment costs or timing) does not necessarily lead to success in terms of the policy’s original goals. However, the challenge when evaluating the effectiveness of public health efforts, especially in an environmental context, requires the development of appropriate metrics for evaluating health changes resulting from different policy approaches (Kingdon 1995; Brownson et al. 2010). This is one of the audit’s key findings. Only a few indicators (Tables 2, 3) demonstrate the AP activities’ good performance with well-documented results, while the majority show either weak performance or could not be evaluated due to poor or absent data. Several indicators defined by the AP are not fit for their intended purpose in terms of evaluating the effectiveness or success of actions (Table 2 indicators 2.2, 3, 4.1, 6, and 7; Table 3 indicators 4.3 and 4.4). Examples of such indicators are those related to drinking water quality and city air pollution associated with public transport. These indicators suffer from unclear goals and intended uses; as a result, it was not possible to evaluate their impact on health improvements. A number of indicators include ‘raising awareness’ and ‘informing the public’ without providing specifics about the events to be included in the evaluation, groups to be addressed, etc. Most of the activities and their indicators do not specifically target children or adolescents but rather focus on the entire population. This presents a barrier in the assessment of associations between environmental quality and specific child and adolescent health outcomes.

The auditing highlighted the issue of inconsistent and indirect associations between specific available environmental quality data and potential (assumed) exposure with specific health outcomes. This is illustrated by an example (Fig. 2), though several have been observed during the audit (National Institute of Public Health 2020a; SEA 2020). Figure 2 shows the issues in determining associations between air quality data and health outcomes (National Institute of Public Health 2020b, c; SEA 2019; Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia 2019). Levels of PM10 and PM2.5 were largely constant in the entire observed period (± 5 µg/m3 seasonal variations) (SEA 2019). That said, the hospitalisation of children and adolescents due to respiratory diseases decreased (National Institute of Public Health 2020b). In the city of Ljubljana, asthma-related hospitalisations increased by almost 35% from 2016 to 2019, while PM10 and PM2.5 concentrations stayed the same or even decreased (National Institute of Public Health 2020c). Changes in hospitalisation due to respiratory diseases could be explained by several reasons not directly associated with air quality, such as behavioural changes, the impact of influenza season, varying health data records in the health information system, different meteorological conditions, variations in sensitivity, etc. Another issue in analysing the data involves inconsistencies in their interpretation, as highlighted in Fig. 2c. The plot presents PM10 and PM2.5 concentrations, while the formal interpretation as provided by the data source defines them as ‘population exposure data’ (Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia 2019). Such inconsistencies hinder the process of evaluating the success of the Strategy.

Air quality and adolescent health in Slovenia between 2013 and 2018. a Annual hospitalisations due to respiratory conditions by age group in Slovenia from 2013 to 2018; b concentrations of PM10 (Slovenia and Ljubljana) and PM2.5 (Ljubljana) from 2013 to 2018; c potential exposure of urban population to PM10 and PM2.5 air pollution in Slovenia from 2011 to 2017; d annual asthma-related hospitalisations in children and adolescents under 20 years of age in Slovenia and Ljubljana from 2016 to 2019

In terms of the IWG’s expected versus actual work, we conclude that there could have been greater transparency, including in its reporting of the Strategy implementation and of goals achieved (based on publicly available information). Moreover, transparency regarding the participation of interested parties is not clear. Collaboration between sectors, NGOs or youth organisations is reported (Ministry of Health of the Republic of Slovenia 2015); however, no information on the effectiveness of such collaborations are available.

Limitations

The audit was performed based on publicly available information. Additional data could improve the overall review of the Strategy and its impacts.

Conclusions

There is no clear evidence that the Strategy has contributed to positive changes in child and adolescent health in Slovenia during the period 2012–2019. Therefore, proposals for future work are as follows:

-

Monitoring policy implementation and its results is crucial, and metrics should be defined in detail along with policy.

-

Environmental health indicators should be fit for their intended purposes.

-

Effective intersectoral work is needed (e.g. a permanent body comprising involved sectors) and is crucial for successful public health interventions (Bjegovic-Mikanovic et al. 2018).

-

Audits should be properly planned and systematically performed. They should be understood as an integral part of monitoring any policy implementation. In this view, no public policy is to be excluded from performance auditing; as has been observed recently, not even those of the WHO (Nature 2020).

-

Re-auditing is vital; without undertaking re-audits regularly, there is no way of knowing whether the midcourse corrections that have been made have improved the situation.

-

Attention should be paid to the current and forthcoming issues affecting the health of young people: sleeping and eating habits, economic migration, changes in family structure, drop in fertility rates, poverty, etc.

References

Bernet PM, Gumus G, Vishwasrao S (2018) Effectiveness of public health spending on infant mortality in Florida, 2001–2014. Soc Sci Med 211:31–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.05.044

Bizjak T, Kontić B (2019) Auditing in addition to compliance monitoring: a way to improve public health. Int J Public Health 64:1259–1260. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-019-01291-4

Bjegovic-Mikanovic V, Santric-Milicevic M, Cichowska A et al (2018) Sustaining success: aligning the public health workforce in South-Eastern Europe with strategic public health priorities. Int J Public Health 63:651–662. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-018-1105-7

Bradley EH, Canavan M, Rogan E et al (2016) Variation in health outcomes: the role of spending on social services, public health, and health care, 2000–2009. Health Aff 35:760–768. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0814

Brownson RC, Seiler R, Eyler AA (2010) Measuring the impact of public health policy. Prev Chronic Dis 7:1–7

Cahill LB, Kane RW, Fleckenstein LJ et al (1987) Environmental audits, 5th edn. Government Institutes Inc, Rockville

Center for Chemical Process Safety (2011) Guidelines for auditing process safety management systems, 2nd edn. Wiley, New York

Donkor A, Luckett T, Aranda S, Phillips J (2018) Barriers and facilitators to implementation of cancer treatment and palliative care strategies in low- and middle-income countries: systematic review. Int J Public Health 63:1047–1057. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-018-1142-2

Dratva J, Stronski S, Chiolero A (2018) Towards a national child and adolescent health strategy in Switzerland: strengthening surveillance to improve prevention and care. Int J Public Health 63:159–161. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-017-1062-6

European Commission (2003) Communication from the Commission to the Council, the European Parliament and the European Economic and Social Committee—A European Environment and Health Strategy. COM/2003/0338 final. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52003DC0338. Accessed 16 Apr 2020

European Commission (2004) Communication from the Commission to the Council, the European Parliament, the European Economic and Social Committee—The European Environment and Health Action Plan 2004–2010. COM/2004/0416 Vol. I final. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=COM:2004:0416:FIN. Accessed 16 Apr 2020

European Commission (2011) The Sixth Environment Action Programme of the European Community 2002–2012—Environment—European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/environment/archives/action-programme/index.htm. Accessed 16 Apr 2020

European Commission (2019) Communication from the commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the council, the European Economic and social committee and the committee of the regions—the European Green Deal. COM(2019) 640 final. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=COM%3A2019%3A640%3AFIN. Accessed 17 Feb 2020

European Court of Auditors (2017) Performance audit manual. Directorate of Audit Quality Control. https://www.eca.europa.eu/Lists/ECADocuments/PERF_AUDIT_MANUAL/PERF_AUDIT_MANUAL_EN.PDF. Accessed 22 Apr 2020

Government of the Republic of Slovenia (2011) Strategy of the Republic of Slovenia on children and adolescent health related to the environment for the period 2012–2020 (in Slovene: Strategija Republike Slovenije za zdravje otrok in mladostnikov v povezavi z okoljem 2012–2020), No: 18100-1/2011/4

Government of the Republic of Slovenia (2015) Action plan for the implementation of the Strategy of the Republic of Slovenia on children and adolescent health related to the environment for the period 2012–2020 (in Slovene: Akcijski načrt za izvajanje strategije Republike Slovenije za zdravje otrok in mladostnikov v povezavi z okoljem 2012–2020), No: 18100-1/2015/4

Gulis G (2019) Compliance, adherence, or implementation? Int J Public Health 64:411–412. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-019-01217-0

International Organization of Supreme Audit Institutions (2004) Performance audit guidelines: ISSAI 3000–3100. International Organization of Supreme Audit Institutions, Vienna

Kaur P (2010) Monitoring tobacco use and implementation of prevention policies is vital for strengthening tobacco control: an Indian perspective. Int J Public Health 55:229–230. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-010-0128-5

Kingdon JW (1995) Agendas, alternatives, and public policies, 2nd edn. Harper Collins, New York (NY)

Legal Information System (2015) Rules on the minimum hygiene requirements for bathing and bathing water in swimming pools (Official Gazette of the Republic of Slovenia, Nos. 59/15, 86/15—Amendments and 52/18). http://www.pisrs.si/Pis.web/pregledPredpisa?id=PRAV12491. Accessed 14 Apr 2020

Mays GP, Smith SA (2011) Evidence links increases in public health spending to declines in preventable deaths. Health Aff 30:1585–1593. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0196

Méndez F, Osorio L (2017) Development and health: keeping hope alive in the midst of irrationality. Int J Public Health 62:175–176. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-016-0892-y

Ministry of Health of the Republic of Slovenia (2015) Report about the work of the intergovernmental working group (in Slovene: Poročilo o delu Medresorske delovne skupine za izvajanje sprejetih zavez na 5. ministrski konferenci o okolju in zdravju v obdobju od 23. 8. 2012 do 31. 5. 2015—predlog za obravnavo). Ljubljana. No: 511-2/2015-44

National Institute of Public Health (2019) Epidemiological monitoring of infectious diseases in Slovenia in 2018 (in Slovene: Epidemiološko spremljanje nalezljivih bolezni v Sloveniji v letu 2018). http://www.nijz.si/sl/epidemiolosko-spremljanje-nalezljivih-bolezni-letna-porocila

National Institute of Public Health (2020a) Slovenian statistical yearbook on health (in Slovene: Zdravstveni statistični letopis Slovenije). https://www.nijz.si/sl/nijz/revije/zdravstveni-statisticni-letopis-slovenije. Accessed 14 Apr 2020

National Institute of Public Health (2020b) Data portal Display by municipalities: Health status (in Slovene: NIJZ Podatkovni portal Prikazi po občinah: Zdravstveno stanje). https://podatki.nijz.si/Menu.aspx?px_tableid = BO01.px&px_path = NIJZ + podatkovni + portal__4 + Zdravstveno + varstvo__06 + Bolni%25u0161ni%25u010dne + obravnave__1 + Hospitalizacije + zaradi + bolezni&px_language = sl&px_db = NIJZ + podatkovni + portal&rxid = 7fe41752-8545-4d36-9490-d. Accessed 22 Apr 2020

National Institute of Public Health (2020c) Data portal K1 Indicators of hospitaizations due to disease (in Slovene: NIJZ Podatkovni portal K1 Kazalniki hospitalizacij zaradi bolezni). https://podatki.nijz.si/Menu.aspx?px_tableid = BO01.px&px_path = NIJZ + podatkovni + portal__4 + Zdravstveno + varstvo__06 + Bolni%25u0161ni%25u010dne + obravnave__1 + Hospitalizacije + zaradi + bolezni&px_language = en&px_db = NIJZ + podatkovni + portal&rxid = 7fe41752-8545-4d36-9490-d. Accessed 22 Apr 2020

Nature (2020) Withholding funding from the World Health Organization is wrong and dangerous, and must be reversed. Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-01121-1

Okorn N (2016) National programme of measures for Roma of the Government of the Republic of Slovenia for the period 2010–2015 (design, structure, implementation of the provisions) (in Slovene: Nacionalni program ukrepov za Rome Vlade RS za obdobje 2010–2015: zasnova, struktura, uresničevanje določb v praksi). Diplomsko delo.. University of Ljubljana, Faculty of Social Sciences

Saeed S, Moodie EEM, Strumpf EC, Klein MB (2019) Evaluating the impact of health policies: using a difference-in-differences approach. Int J Public Health 64:637–642. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-018-1195-2

Shankar AN, Shankar VN, Praveen V (2011) Basics in research methodology—the clinical audit. J Clin Diagn Res 5(3):679–682

Singh SR (2014) Public health spending and population health: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med 47:634–640. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2014.05.017

Slovenian Environment Agency (2019) Air pollution by particulate matter (in Slovene: Onesnaženost zraka z delci PM10 in PM2.5). http://kazalci.arso.gov.si/sl/content/onesnazenost-zraka-z-delci-pm10-pm25-5. Accessed 18 Apr 2020

Slovenian Environment Agency (2020) Human health and ecosystem resilience (in Slovene: Zdravje ljudi in ekosistemov). http://kazalci.arso.gov.si/sl/teme/human-health-and-ecosystem-resilience. Accessed 18 Apr 2020

Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia (2019) 11.3 Urban population exposure to air pollution by particulate matter. https://www.stat.si/Pages/en/goals/goal-11.-make-cities-and-human-settlements-inclusive-safe-resilient-and-sustainable/11.4-urban-population-exposure-to-air-pollution-by-particulate-matter. Accessed 22 Apr 2020

Usmanova G, Mokdad AH (2013) Results of the Global Youth Tobacco Survey and implementation of WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control in former Soviet Union countries. Int J Public Health 58:217–226. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-012-0433-2

van den Driessen Mareeuw F, Vaandrager L, Klerkx L et al (2015) Beyond bridging the know-do gap: a qualitative study of systemic interaction to foster knowledge exchange in the public health sector in The Netherlands. BMC Public Health 15:922. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-2271-7

WHO Regional Office for Europe (2010) Fifth Ministerial Conference on Environment and Health “Protecting children’s health in a changing environment”, Parma, Italy, 10–12 March 2010 (Parma Declaration, EUR/55934/5.1 Rev. 2, 11 March 2010, 100604). http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0011/78608/E93618.pdf. Accessed 15 Apr 2020

Funding

NEUROSOME innovative Training Network funded by the Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Grant Agreement No. 766251 funded the work of Tine Bizjak and the Slovenian Research Agencies “Young researchers” program which funded the work of Rok Novak.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors. Formal consent is not required for this type of study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the special issue “Adolescent Health in Central and Eastern Europe”.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bizjak, T., Novak, R., Vudrag, M. et al. Evaluating the success of Slovenia’s policy on the health of children and adolescents: results of an audit. Int J Public Health 65, 1225–1234 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-020-01432-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-020-01432-0