Summary

Interactions of singing humpback whales, Megaptera novaeangliae, with conspecifics nearly were studied during the breeding season off the west coast of Maui, Hawaii. On 35 occasions singing humpbacks were followed by boats (Table 1). The movement patterns of these singing whales and other conspecifics nearby were recorded by observers on land using a theodolite.

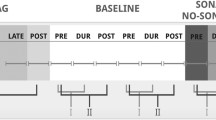

Thirteen of 35 singers stopped singing and joined with nonsinging whales either simultaneously or within a few minutes after ceasing to sing. Another 15 also stopped singing while under observation and were not seen to join with another whale, but all singing whales that joined with other whales stopped singing. Singing whales often pursue nonsinging whales, while nonsinging whales usually turn away from singers (Figs. 4, 5).

When a singer joined with a female and calf unaccompanied by another adult, behavior tentatively associated with courtship and mating was observed (Fig. 7). Such behavior also occurred during several interactions between singers and individuals of unknown sex. Aggressive behavior was observed during three interactions between singers and individuals of unknown sex (Fig. 4) and it predominated whenever more than one adult accompanied a cow and calf. During the other occasions when a singer joined another whale, we could not determine the nature of the interaction. Many times the singers and joiner would surface together only once and would then separate. However, on several occasions the singer and joiner would remain together for as long as we could follow them, up to 1.5 h.

The roles of singer and joiner can be interchangeable. For instance, on two occasions a singer joined with a whale that either had been singing or started singing later in the day (Fig. 3). Furthermore, on several occasions, a nonsinging whale appeared to displace the singer. Individual singing humpbacks are not strictly territorial, although singers appear to avoid other singers.

As the breeding season progressed, singers sang for longer periods of time (Fig. 2). In addition, the probability of a whale joining with the singer decreased by 42% from the first half of the observation period to the second half. Furthermore, this increase in duration of song bouts occurred during that section of the season when female reproductive activity as measured by rate of ovulation is reported to be decreasing in other areas.

Our observations support the hypothesis that humpback song plays a reproductive role similar to that of bird song. Humpbacks sing only during the breeding season. If, as seems likely, most singing humpbacks are male, then singing humpbacks probably communicate their species, sex, location, readiness to mate with females, and readiness to engage in agonistic behavior with other whales.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Alexander RD (1960) Sound communication in Orthoptera and Cicadidae. In: Lanyon WE, Tavolga WN (eds) Animal sounds and communication. American Institute of Biological Sciences, Washington, DC, pp 38–92

Armstrong EA (1963) A study of bird song. Oxford University, London

Brockway BF (1969) Roles of budgerigar vocalization in the integration of breeding behavior. In: Hinde RA (ed) Bird vocalizations. Cambridge University, Cambridge, pp 131–158

Chittleborough RG (1953) Aerial observations on the humpback whale, Megaptera nodosa (Bonaterre) with notes on other species. Aust J Mar Freshw Res 4:219–226

Chittleborough RG (1954) Studies on the ovaries of the humpback whale, Megaptera nodosa (Bonaterre) on the West Australian coast. Aust J Mar Freshw Res 5:35–63

Chittleborough RG (1955) Aspects of reproduction in the male humpback whale, Megaptera nodosa (Bonaterre). Aust J Mar Freshw Res 6:1–29

Chittleborough RG (1958) The breeding cycle of the female humpback whale, Megaptera nodosa (Bonaterre). Aust J Mar Freshw Res 9:1–18

Chittleborough RG (1965) Dynamics of two populations of the humpback whale, Megaptera novaeangliae (Borowski). Aust J Mar Freshw Res 16:33–128

Dawbin W (1956) The migrations of humpback whales which pass the New Zealand coast. Trans R Soc NZ 84:147–196

Donnelly BG (1967) Observations on the mating behaviour of the southern right whale, Eubalaena australis. S Afr J Sci 63:176–181

Donnelly BG (1969) Further observations on the southern right whale, Eubalaena australis, in South African waters. J Reprod Fertil Suppl 6:347–352

Eisner E (1960) The relationship of hormones to the reproductive behaviour of birds, referring especially to parental behavior: A review. Anim Behav 8:155–179

Herman LM, Antinoja RC (1977) Humpback whales in the Hawaiian breeding waters: population and pod characteristics. Sci Rep Whales Res Inst 29:59–85

Houck WJ (1962) Possible mating of grey whales on the northern California coast. Murrelet 43:54

Hudnall J (1977) In the company of great whales. Audubon 79:62–73

Katona S, Baxter B, Brazier O, Kraus S, Perkins J, Whitehead H (1979) Identification of humpback whales by fluke photographs. In: Winn HE, Olla BL (eds) Behavior of marine mammals, vol 3, Cetaceans. Plenum, New York, pp 33–44

Krebs JR (1977) Song and territory in the great tit Parus major. In: Stonehouse B, Perrins CM (eds) Evolutionary ecology. MacMillan, London, pp 47–62

Kroodsma DE (1976) Reproductive development in a female songbird: differential stimulation by quality of male song. Science 192:574–575

Marler P (1956) The voice of the chaffinch and its function as a language. Ibis 98:231–261

Marler P (1965) Aggregation and dispersal: two functions in primate communication. In: Jay PC (ed) Primates studies in adaptation and variability. Holt, Rinehardt and Winston, New York, pp 420–438

Marshall JT, Ross BA, Chantharojuong S (1972) The species of gibbons in Thailand. J Mammal 53:479–486

Matthews LH (1937) The humpback whale, Megaptera nodosa. Discovery Rep 17:7–92

Newman JR (1976) Observations of sexual behavior in male gray whales, Eschrichtius robustus. Murrelet 57:49

Nishiwaki M (1959) Humpback whales in Ryukyuan waters. Sci Rep Whales Res Inst 14:49–87

Nishiwaki M (1960) Ryukyuan humpback whaling in 1960. Sci Rep Whales Res Inst 15:1–15

Nishiwaki M (1962) Ryukyuan whaling in 1961. Sci Rep Whales Res Inst 16:19–28

Nishiwaki M, Hayashi K (1950) Copulation of humpback whales. Sci Rep Whales Res Inst 3:183

Payne RS (1970) The whale. CRM Books, Del Mar, CA (booklet accompanying Capitol record ST-620, Song of the humpback whale)

Payne RS (1976) At home with right whales. Nat Geog 149:3:322–339

Payne RS, McVay S (1971) Songs of humpback whales. Science 173:585–597

Saayman GS, Tayler CK (1973) Some behaviour patterns of the southern right whale Eubalaena australis. Z Säugetierk 38:172–183

Samaras WF (1974) Reproductive behaviour of the gray whale, Eschrichtius robustus, in Baja California. Bull South Calif Acad Sci 73:57–64

Sauer EGF (1963) Courtship and copulation of the gray whale in the Bering Sea at St. Lawrence Island, Alaska. Psychol Forsch 27:157–174

Scammon CN (1874) The marine mammals of the North-western coast of North America with an account of the American whale fishery. Carmany, San Francisco, CA

Schevill WB (1966) Underwater sounds of cetaceans. In: Tavolga WN (ed) Marine bio-acoustics. Pergamon, Oxford, pp 307–317

Shallenberger EW (1976) Report to Seaflite and Sea Grant on the population and distribution of humpback whales in Hawaii. In: Mimeo, Honolulu Sea Life Park

Wilson EO (1975) Sociobiology: The new synthesis. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

Winn HE, Perkins PJ, Poulter TC (1970) Sounds of the humpback whale. In: Seventh annual congress on biological sonar. Stanford Research Institute, Menlo Park

Winn HE, Bischoff WL, Taruski AG (1973) Cytological sexing of cetacea. Mar Biol 23:343–346

Winn HE, Winn LK (1978) The song of the humpback whale Megaptera novaengliae in the West Indies. Mar Biol 47:97–114

Würsig B (1978) On the behavior and ecology of bottlenose and dusky porpoises in the South Atlantic. Ph D thesis at SUNY, Stony Brook, NY

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tyack, P. Interactions between singing Hawaiian humpback whales and conspecifics nearby. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 8, 105–116 (1981). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00300822

Received:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00300822