Abstract

Chemotherapy toxicity relies on the mechanism of action of the drugs, the doses, the way of administration, and underlying predisposing factors like cardiac conditions, genetic pattern, and age and can manifest itself immediately or many years after. Concomitant treatments and radiotherapy can interfere with toxicity. Irreversible cytotoxicity (type I agents) or interaction with functional aspects of cardiac cells not primarily cytotoxic (type II agents) may lead to heart failure. Furthermore arterial hypertension, venous and arterial thromboembolism, myocardial ischemia and infarction, and arrhythmias may develop with several chemotherapy agents.

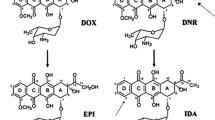

The cellular toxicity of chemotherapy agents is related to ROS generation, mitochondrial dysfunction, SERCA dysfunction, and sarcomere degradation for anthracyclines; to inhibition of the synthesis of RNA and DNA for fluoropyrimidines; to cross-linkage of DNA strands preventing the uncoiling and leading to DNA breaking and apoptosis for alkylating agents; to prevention of formation and disassembly of the microtubules of the mitotic spindle essential for a correct mitosis for anti-microtubule agents; to vascular rarefaction and damage of NO production of VEGF inhibitors; and to inhibition of HER2 pathway with protective, growth promoter, and antiapoptotic role.

Incidence of acute toxicity may be very rare or quite frequent for different drugs. Also chronic toxicity incidence is variable and may develop over long time period.

Clinical signs and symptoms, electrocardiographic modifications, chest X-ray, troponin and natriuretic peptide elevations, and mainly echocardiographic signs (LVEF and strain methods) may identify chemotherapy toxicity.

Several strategies have been proposed for the prevention and the treatment of the different chemotherapy drug toxicities, based on the accurate patient’s selection, monitoring, and ACE inhibitors and beta-blockers when left ventricular dysfunction develops.

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Similar content being viewed by others

Bibliography

Mann DL. Mechanisms and models in heart failure: the biochemical model and beyond. Circulation. 2005;111:2837.

Ewer MS. Reversibility of Trastuzumab-related cardiotoxicity: new insights based on clinical course and response to medical treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7820.

Sawyer DB. Modulation of anthracycline-induced myofibrillar disarray in rat ventricular myocytes by neuregulin-1beta and anti-erbB2: potential mechanism for trastuzumab-induced cardiotoxicity. Circulation. 2002;105(13):1551.

Telli ML. Trastuzumab-induced cardiotoxicity: calling into question the concept of reversibility. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3525.

Ederhy S. Cardiac side effects of molecular targeted therapies: towards a better dialogue between oncologists and cardiologists. Clin Rev Oncol Hematol. 2011. doi:10.1016/j.eritrevonc.2011.01.009

Tan C. Daunomycin, an antitumor antibiotic, in the treatment of neoplastic disease. Clinical evaluation with special reference to childhood leukemia. Cancer. 1968;20(3):333.

Swain SM. Congestive heart failure in patients treated with doxorubicin: a retrospective analysis of three trials. Cancer. 2003;97:2869.

Nousiainen T. Natriuretic peptides during the development of doxorubicin-induced left ventricular diastolic dysfunction. J Intern Med. 2002;251:228.

Lipshultz SE. Chronic progressive cardiac dysfunction years after doxorubicin therapy for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2629.

Wojonowski L. NAD(P)H oxidase and multidrug resistance protein genetic polymorphism are associated with doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. Circulation. 2005;112:3754.

Smith LA. Cardiotoxicity of anthracycline agents for the treatment of cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:337.

Ewer MS. A comparison of cardiac biopsy grades and ejection fraction estimations in patients receiving Adriamycin. J Clin Oncol. 1984;2:112.

Lefrak EA. A clinicopathologic analysis of Adriamycin cardiotoxicity. Cancer. 1973;32:302.

Cardinale D. Myocardial injury revealed by plasma troponin I in breast cancer treated with high-dose chemotherapy. Ann Oncol. 2002;13:710.

Bristow MR. Clinical spectrum of anthracycline antibiotic cardiotoxicity. Cancer Treat Rep. 1978;62:873.

Lipshults SE. The effect of dexrazoxane on myocardial injury in doxorubicin-treated children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:145.

Swain SM. Cardioprotection with dexrazoxane for doxorubicin-containing therapy in advanced breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1997;35:1318.

Swain SM. Delayed administration of dexrazoxane provides cardioprotection for patients with advanced breast cancer treated with doxorubicin-containing therapy. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:1333.

Ewer MS. Cardiac safety of liposomal anthracyclines. Semin Oncol. 2004;31:161.

Takemura G. Doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy from the cardiotoxic mechanisms to management. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2007;49:330.

Fernandez SF. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy following initial chemotherapy presenting with syncope and cardiogenic shock – a case report and literature review. J Clin Exp Cardiol. 2001;2:124.

Singal PK. Subcellular effects of adriamycin in the heart: a concise review. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1987;19:817.

Grenier MA. Epidemiology of anthracycline cardiotoxicity in children and adults. Semin Oncol. 1998;25(4 Suppl 10):72.

Mulrooney DA. Cardiac outcomes in a cohort of adult survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer retrospective analysis of the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study cohort. BMJ. 2009;339:b4606.

Abu-Khalaf MM. Long-term assessment of cardiac function after dose-dense and -intense sequential doxorubicin (A) paclitaxel (T) and cyclophosphamide (C) as adjuvant therapy for high risk breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;104(3):341.

Billingham ME. Anthracycline cardiomyopathy monitored by morphologic changes. Cancer Treat Rep. 1978;62:865.

Buja LM. Cardiac ultrastructural changes induced by daunorubicin therapy. Cancer. 1973;32:771.

Von Hoff DD. Risk factors for doxorubicin-induced congestive heart failure. Ann Intern Med. 1979;01:710.

O’Brien ME, CAELIX Breast Cancer Study Group. Reduced cardiotoxicity and comparable efficacy in a phase III trial of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin HCL (CAELIXDTM/Doxil®) versus conventional doxorubicin for first line treatment of metastatic breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2004;15:440.

van Dalen EC. Cardioprotective interventions for cancer patients receiving anthracyclines. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(6):CD003917.

van Dalen EC. Different anthracycline derivates for reducing cardiotoxicity in cancer patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(5):CD005006.

van Dalen EC. Different dosage schedules for reducing cardiotoxicity in cancer patients for reducing cardiotoxicity in cancer patients receiving anthracycline chemotherapy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(4):CD005008.

Cole MP. The protective roles of nitric oxide and superoxide dismutase in adriamycin-induced cardiotoxicity. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;69(1):186.

Daosukho C. Induction of manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD) mediates cardioprotective effect of tamoxifen (TAM). J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2005;39(5):792.

Volkova M. Activation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor by doxorubicin mediates cytoprotective effects in the heart. Cardiovasc Res. 2011;90:305.

Neilan TG. Disruption of nitric oxide synthase 3 protects against the cardiac injury dysfunction and mortality induced by doxorubicin. Circulation. 2007;116(5):506.

Dowd NP. Inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2 aggravates doxorubicin-mediated cardiac injury in vivo. J Clin Invest. 2001;108(4):585.

Kotamraju S. Doxorubicin-induced apoptosis in endothelial cells and cardiomyocytes is ameliorated by nitrone spin traps and ebselen. Role of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(43):33585.

Chua CC. Multiple actions of pifithrin-alpha on doxorubicin-induced apoptosis in rat myoblastic H9c2 cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;290(6):H2606.

Wang L. Regulation of cardiomyocyte apoptotic signaling by insulin-like growth factor I. Circ Res. 1998;83(5):516.

Childs AC. Doxorubicin treatment in vivo causes cytochrome C release and cardiomyocyte apoptosis as well as increased mitochondrial efficiency superoxide dismutase activity and Bcl-2 Bax ratio. Cancer Res. 2002;62(16):4592.

Wang GW. Metallothionein inhibits doxorubicin-induced mitochondrial cytochrome c release and caspase-3 activation in cardiomyocytes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;298(2):461.

Palfi A. The role of Akt and mitogen-activated protein kinase systems in the protective effect of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibition in Langendorff perfused and in isoproterenol-damaged rat hearts. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;315(1):273.

Toth A. Impact of a novel cardioprotective agent on the ischemia-reperfusion-induced Akt kinase activation. Biochem Pharmacol. 2003;66(11):2263.

Toth A. Akt activation induced by an antioxidant compound during ischemia-reperfusion. Free Radic Biol Med. 2003;35(9):1051.

Nagy N. Overexpression of glutaredoxin-2 reduces myocardial cell death by preventing both apoptosis and necrosis. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2008;44(2):252.

Pastukh V. Contribution of the PI 3-kinase/Akt survival pathway toward osmotic preconditioning. Mol Cell Biochem. 2005;269(1–2):59.

Russell SD. Independent adjudication of symptomatic heart failure with the use of doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide followed by trastuzumab adjuvant therapy a combined review of cardiac data from the National Surgical Adjuvant breast and Bowel Project B-31 and the North Central Cancer Treatment Group N9831 clinical trials. J Clin Oncol: Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol Clin Trial Res Support Non US Govt. 2010;28(21):3416.

Estorch M. Indium-111-antimyosin scintigraphy after doxorubicin therapy in patients with advanced breast cancer. J Nucl Med. 1990;31:1965.

Volkova M. Anthracycline cardiotoxicity: prevalence, pathogenesis and treatment. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2011;7(4):214.

Chatterjee K. Vincristine attenuates doxorubicin cardiotoxicity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;373:555.

Cardinale D. Anthracycline-induced cardiomyopathy: clinical relevance and response to pharmacologic therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55(3):213.

Alter P. Cardiotoxicity of 5-fluorouracil. Cardiovasc Hematol Agents Med Chem. 2006;4(1):1.

Becker K. Cardiotoxicity of the antiproliferative compound fluorouracil. Drugs. 1999;57(4):475.

Saif MW. Fluoropyrimidine-associated cardiotoxicity: revisited. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2009;8(2):191–202. doi:10.1517/14740330902733961.

Endo A. Capecitabine induces both cardiomyopathy and multifocal cerebral leukoencephalopathy. Int Heart J. 2013;54(6):417.

Shah NR. Ventricular fibrillation as a likely consequence of capecitabine-induced coronary vasospasm. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2012;18(1):132. doi:10.1177/1078155211399164. Epub 2011 Feb 14.

Y-Hassan S. Capecitabine caused cardiogenic shock through induction of global Takotsubo syndrome. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2013;14(1):57. doi:10.1016/j.carrev.2012.10.001. Epub 2012 Dec 5.

Kufe DW, editor. Alkylating agents Holland-Frei cancer medicine. 6th ed. Hamilton: BC Decker; 2003.

Cascales A. Clinical and genetic determinants of anthracycline-induced cardiac iron accumulation. Int J Cardiol. 2012;154(3):282.

Zhang S. Identification of the molecular basis of doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. Nat Med. 2012;18:1639.

Leone TC. Transcriptional control of cardiac fuel metabolism and mitochondrial function. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2011;76:175.

Chee Chew L. Anthracyclines induce calpain-dependent titin proteolysis and necrosis in cardiomyocytes. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:8290.

Prezioso L. Cancer treatment-induced cardiotoxicity: a cardiac stem cell disease? Cardiovasc Hematol Agents Med Chem. 2010;8(1):55.

Arbel Y. QT prolongation and Torsades de Pointes in patients previously treated with anthracyclines. Anticancer Drugs. 2007;18(4):493.

Saadettin K. Doxorubicin-induced second degree and complete atrioventricular block. Europace. 2005;7:227.

Alehan D. Tissue Doppler evaluation of systolic and diastolic cardiac functions in long-term survivors of Hodgkin lymphoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;58:250.

Shan K. Anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125:47.

Nakamae H. QT dispersion correlates with systolic rather than diastolic parameters in patients receiving anthracycline therapy. Intern Med. 2004;43:379.

Couch RD. Sudden cardiac death following adriamycin therapy. Cancer. 1981;48:38.

Nagla A. Protective effect of carvedilol on adriamycin-induced left ventricular dysfunction in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Card Fail. 2012;18:607.

Nakamae H. Notable effects of angiotensin II receptor blocker, valsartan, on acute cardiotoxic changes after standard chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and methylprednisolone. Cancer. 2005;104(11):2492.

Minotti G. Pharmacology at work for cardio-oncology: ranolazine to treat early cardiotoxicity induced by antitumor drugs. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2013;346:343.

Paul F. Early mitoxantrone-induced cardiotoxicity in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78(2):198.

Yeh ETH. Cardiovascular complications of cancer therapy: incidence, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53(24):2231.

Altena R. Longitudinal changes in cardiac function after cisplatin-based chemotherapy for testicular cancer. Ann Oncol. 2011;22(10):2286.

Togna GI. Cisplatin triggers platelet activation. Thromb Res. 2000;99(5):503.

Kuenen BC. Potential role of platelets in endothelial damage observed during treatment with cisplatin, gemcitabine, and the angiogenesis inhibitor SU5416. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(11):2192.

Guglin M. Introducing a new entity: chemotherapy-induced arrhythmia. Europace. 2009;11:1579.

Dumontet C. BCIRG 001 molecular analysis: prognostic factors in node-positive breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16(15):3988.

Rowinsky EK. Cardiac disturbances during the administration of taxol. J Clin Oncol. 1991;9:1704.

Kolfschoten GM. Variation in the kinetics of caspase-3 activation, Bcl-2 phosphorylation and apoptotic morphology in unselected human ovarian cancer cell lines as a response to docetaxel. Biochem Pharmacol. 2002;63(4):723.

Force T. Molecular mechanisms of cardiotoxicity of tyrosine kinase inhibition. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:332.

Lipshultz SE. Long-term cardiovascular toxicity in children, adolescents and young adults who receive cancer therapy: pathophysiology, course, monitoring, management, prevention and research directions: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013;128:1927. doi:doi:10.1016/j.eritrevonc.2011.01.009.

Yeh TH. Cardiovascular complications of cancer therapy diagnosis, pathogenesis, and management. Circulation. 2004;109:3122.

Pereg D. Bevacizumab treatment for cancer patients with cardiovascular disease: a double edged sword? Eur Heart J. 2008;29:2325.

Scappaticci FA. Arterial thromboembolic events in patients with metastatic carcinoma treated with chemotherapy and bevacizumab. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99(16):1232.

Curigliano G. Cardiac toxicity from systemic cancer therapy: a comprehensive review. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2010;53:94.

Curigliano G. Cardiovascular toxicity induced by chemotherapy, targeted agents and radiotherapy: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(7):vii 155.

Schmidinger M. Cardiac toxicity of sunitinib and sorafenib in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(32):5204.

Kaminetzky D. Denileukin diftitox for the treatment of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Biologics. 2008;2(4):717.

Frankel SR. The “retinoic acid syndrome” in acute promyelocytic leukemia. Ann Intern Med. 1992;117(4):292.

Barbey JT. Effect of arsenic trioxide on QT interval in patients with advanced malignancies. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(19):3609.

Unnikrishnan D. Cardiac monitoring of patients receiving arsenic trioxide therapy. Br J Haematol. 2004;124(5):610.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Asteggiano, R. (2015). Physiopathology and Toxic Heart Effects of Chemotherapy Drugs. In: Baron Esquivias, G., Asteggiano, R. (eds) Cardiac Management of Oncology Patients. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-15808-2_2

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-15808-2_2

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-15807-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-15808-2

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)