Abstract

This chapter addresses social enterprises as a special corporate category, which in some European jurisdictions, and increasingly so after their promotion by the European Union, are provided with a specific legal framework to promote and encourage their development. The paper begins with a brief compilation of the several social enterprise concepts developed by economic doctrines both in the United States and Europe, which reveal a great diversity of approaches. This is followed by an analysis of the various documents published by the European Union, showing the increasing recognition of this business phenomenon, from the publication of the Social Business Initiative in 2011 to the recent Action Plan for the Social Economy in 2021. Finally, the results obtained from the analysis of the different European legal systems are presented, and three main models of legal regulation of social enterprises are distinguished, namely, the use of the social cooperative form, enactment of a special law, and integration into a social economy law. The chapter concludes with a table comparing the essential aspects of the regulation of social enterprises in 14 European countries.

This publication is one of the results of the R&D&I project UAL2020-SEJ-C2085, under the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) Andalusia 2014–2020 operational program, entitled “Corporate social innovation from Law and Economics.”

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 The Doctrinal Concept of Social Enterprise in Europe

In Europe, the origin of the doctrinal recognition of social enterprise is usually said to have started in 1990 in Italy with the launch of the scientific journal Impresa Sociale upon the initiative of the Centro Studi del Consorzio (CGM).Footnote 1 CGM elaborates the concept of a social enterprise that is attached to the traditional figure of cooperatives, but with a change in orientation to respond to social initiatives not satisfied by the market, especially in the field of labor integration and social services. When the law governing social cooperatives was passed in 1991, this doctrinal concept quickly gained legal recognition in that country, and an initiative was later adopted by other European countries.Footnote 2 However, following this initial approach, different doctrinal conceptions of social enterprise developed in Europe, with a distinction being made between more open-minded positions and others that have attempted to link them to the social economy movement.

In this process, an extensive European network of researchers called Emergence des Entreprises Sociales en Europe, created in 1996 within the framework of an important research project of the European Commission, whose acronym was maintained when the project ended in 2000, became an international scientific association under the name EMES Research Network for Social Enterprise, which still operates with considerable academic intensity.Footnote 3 The EMES network made a commendable effort to identify entities that could be qualified as social enterprises in the 15 countries that made up the European Union (EU) at that time and with a multidisciplinary theoretical-practical approach. Considering the different perceptions of social enterprise in the various countries analyzed, EMES was able to identify nine indicators that serve to define the three dimensions of social enterprise, which are listed below without going into their individualized content:Footnote 4

-

1.

The economic and entrepreneurial dimensions of social enterprises:

-

(a)

A continuous activity producing goods and/or selling services

-

(b)

A significant level of economic risk

-

(c)

A minimum amount of paid work

-

(a)

-

2.

The social dimensions of social enterprises:

-

(d)

An explicit aim to benefit the community

-

(e)

An initiative launched by a group of citizens

-

(f)

A limited profit distribution

-

(d)

-

3.

Participatory governance of social enterprises:

-

(g)

A high degree of autonomy

-

(h)

A decision-making power not based on capital ownership

-

(i)

A participatory nature, which involves various parties affected by the activity

-

(g)

These indicators describe an ideal type of social enterprise, but they do not represent the conditions that an organization must necessarily meet to be classified as such, nor are they intended to provide a structured concept of social enterprise. Rather, they serve to indicate a range within which organizations can move to be classified as social enterprises. As has been graphically pointed out by two of the leading European authors on the subject, such indicators constitute a tool that is somewhat analogous to a compass, which helps the researchers locate the position of the observed entities relative to one another and eventually identify subsets of social enterprises they want to study more deeply, allowing new social enterprises to be identified and old organizations to be restructured by means of new internal dynamics to be designated as such.Footnote 5 This doctrinal concept of social enterprise had a great influence on several European Union documents and on the content of some of the different laws passed by European countries to regulate them, as we shall see below.

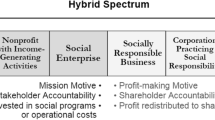

However, this concept of dominant social enterprise in Europe responds, to a certain extent, to a tradition linked to the traditional forms of social economy, such as cooperatives, mutual insurance companies, and company foundations, which are those that usually comply with the organizational and financial requirements that are demanded by law (limits to the profit motive, voting of members not based on capital stock, etc.). This European doctrinal concept contrasts with the dominant one in North American literature, which focuses more on the achievement of a social purpose or on the way to achieve it than on the formal requirements to be met by the entities that achieve it.

In the United States, there are two main doctrinal approaches to social enterprises.Footnote 6 The first school of thought, known as the social enterprise school of thought, considers the use of business activities for profit to achieve a fundamental social purpose. Although this vision of a social-mission-oriented business strategy focused only on nonprofit organizations, it gradually expanded to encompass all organizations that seek to achieve a social purpose or mission, including for-profit organizations, such as corporations. The second doctrinal perspective on social enterprise is known as the social innovation school of thought, which emphasizes the profile and behavior of social entrepreneurship based on Schumper’s theory of the innovative entrepreneur and focuses more on the social impact generated by the development of a socially innovative activity (new services, production methods, forms of organization, markets, etc.) than on the income generated by the entity, even if it serves to support a social mission.Footnote 7 However, as noted above,Footnote 8 the differences between the two North American schools are neither so great nor so obvious since they have ended up imposing an expanded vision of the social purpose of companies in the sense that they can produce both economic and social value, which has been called the double (or triple if environmental value is broken down into a separate category) impact or blended value of companies.Footnote 9

As a corollary to this epigraph, I will take up the definition of social enterprise provided by two well-known economists, which serves to highlight the enormous and diverse concepts of social enterprises. Bill Drayton, founder of Ashoka, a nonprofit organization that brings together social entrepreneurs from all over the world and promotes innovative ideas for social transformation, considers social entrepreneurs to be people taking an innovative approach, with all their energy, passion, and tenacity, to solve the most important problems of our societies.Footnote 10

Muhammad Yunus, recipient of the 2006 Noble Peace Prize for implementing the concept of microcredit beginning in 1974 and founding the Grameen Bank (village in his native language) in 1983, simply defined social enterprise as non-loss, a non-dividend enterprise is designed to address a social objective.Footnote 11

2 Promotion and Recognition of Social Enterprise by the European Union: From the SBI Initiative to the New Action Plan for the Social Economy

In the European Union, the “Social Business Initiative. Creating a favorable climate for social enterprises, key stakeholders in the social economy and innovation” (2011),Footnote 12 cited as SBI, launched 11 years ago in the midst of the economic crisis, is a milestone in promoting recognition of the importance of social enterprises and social innovation in the search for original solutions to social problems and, specifically, in the fight against poverty and social exclusion. However, there were several initiatives to promote social enterprises developed by different EU bodies and institutions prior to the SBI, although none were important. Two of them can be pointed out: “European Parliament resolution on Social Economy” (2009)Footnote 13 and “The European Platform against Poverty and Social Exclusion: A European framework for social and territorial cohesion” (2010).Footnote 14

Among other objectives of the SBI, the need to improve the legal framework for social enterprises at the European level is highlighted since neither the EU nor the national level had sufficiently considered this alternative form of enterprise. Without claiming to be normative, the SBI proposes a description of social enterprises based on a series of common characteristics, such as those:Footnote 15

-

In which the social or societal objective of the common good is the reason for commercial activity, often in the form of a high level of social innovation

-

Where profits are mainly reinvested with a view to achieving this social objective

-

Where the method of organization or ownership system reflects their mission, using democratic or participatory principles, or focusing on social justice

These companies, SBI continues, can be of two types:

-

“Businesses providing social services and/or goods and services to vulnerable persons” (access to housing, health care, assistance for elderly or disabled persons, inclusion of vulnerable groups, childcare, access to employment and training, dependency management, etc.); and/or

-

“Businesses with a method of production of goods or services with a social objective (social and professional integration via access to employment for people disadvantaged in particular by insufficient qualifications or social or professional problems leading to exclusion and marginalization) but whose activity may be outside the realm of the provision of social goods or services,” such as companies dedicated to the labor market integration of people at risk of exclusion, which is known as work integration social enterprises (WISE)

After the enactment of the SBI, numerous official documents of the European Union were drafted to insist on the promotion and recognition of social enterprises and social entrepreneurship. Without being exhaustive, in the first post-SBI stage, the Opinion of the European Economic and Social Committee on “Social entrepreneurship and social enterprise” (exploratory opinion) (2011)Footnote 16 and the European Parliament resolution on “Social Business Initiative – Creating a favorable climate for social enterprises, key stakeholders in the social economy and innovation” (2012)Footnote 17 are worth mentioning because of their significance. In the Resolution (paragraph 3 of the Introduction), it is stated that social enterprise means an undertaking, regardless of its legal form, that:

-

Has the achievement of measurable, positive social impact as a primary objective in accordance with its articles of association, statutes, or any other statutory document establishing the business, where the undertaking provides services or goods to vulnerable, marginalized, disadvantaged, or excluded persons, and/or provides goods or services through a method of production, which embodies its social objective

-

Uses its profits first and foremost to achieve its primary objectives instead of distributing profits, and has predefined procedures and rules for any circumstances in which profits are distributed to shareholders and owners, which ensures that any such distribution of profits does not undermine its primary objectives

-

Is managed in an accountable and transparent way, in particular by involving workers, customers, and/or stakeholders affected by business activities

In 2013, several official documents recognizing the importance and interest of social enterprises were promulgated by different European Union bodies, such as the following: Communication from the Commission “Towards Social Investment for Growth and Cohesion – including implementing the European Social Fund 2014–2020,”Footnote 18 Regulation (EU) No. 346/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council on “European social entrepreneurship funds,” and Regulation (EU) No. 1296/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 December 2013 on a European Union Programme for Employment and Social Innovation (“EaSI”) and amending Decision No. 283/2010/EU establishing a European Progress Microfinance Facility for employment and social inclusion Text with EEA relevance. Article 2 of the latter regulation states that social enterprise means an undertaking regardless of its legal form:

-

In accordance with its articles of association, statutes, or with any other legal document by which it is established, its primary objective is the achievement of measurable, positive social impacts rather than generating profit for its owners, members, and shareholders, which provides services or goods that generate a social return and/or employs a method of production of goods or services that embodies its social objective;

-

Uses its profits primarily to achieve its primary objective and has predefined procedures and rules covering any distribution of profits to shareholders and owners that ensure that such distribution does not undermine the primary objective; and

-

Is managed in an entrepreneurial, accountable, and transparent way, particularly by involving workers, customers, and stakeholders affected by business activities.

Subsequently, other documents have continued to be issued that refer, in one way or another, to the role that social enterprises should play in the European economy; however, in several of them, there has been an evolution toward the absorption of social enterprise by the broader concept of social economy, which in many cases is now referred to as solidarity-based. There is a paradoxical process of broadening the subjects that can form part of the social economy (already admitting trading companies when they meet certain conditions) but simultaneously reducing its scope to organizations more oriented toward the general interest or public utility that has a lasting and positive impact on economic development and the welfare of society and not only those that seek a mutualistic objective of satisfying the interests of the members.Footnote 19

An example of this can be found in the European Parliament resolution of September 10, 2015, on social entrepreneurship and social innovation in combating unemployment,Footnote 20 which with regard to social and solidarity-based economy enterprises notes, in its introduction, that:

They do not necessarily have to be non-profit organizations; they are enterprises whose purpose is to achieve their social goal, which may be to create jobs for vulnerable groups, provide services for their members, or more generally create a positive social and environmental impact, and which reinvest their profits primarily in order to achieve those objectives.

It is characterized by its commitment to the classic values of the social economy: the primacy of individual and social goals over the interests of capital, democratic governance by members, the conjunction of the interests of members and users and the general interest, the safeguarding and application of the principles of solidarity and responsibility, the reinvestment of surplus funds in long-term development objectives or in the provision of services that are of interest to members or of general interest, voluntary and open membership, and autonomous management independent of public authorities.

Another clear example can be noted in the European Parliament resolution with recommendations to the Commission on a “Statute for social and solidarity-based enterprises” (2018),Footnote 21 which in its first recommendation points out that the European Social Economy Label that is intended to be created will be optional for enterprises based on the social economy and solidarity (social and solidarity-based enterprises), regardless of the legal form they decide to adopt, provided that they comply with the following criteria in a cumulative manner:

The organization should be a private law entity established in whichever form is available in Member States and under EU law, and should be independent from the state and public authorities;

Its purpose must be essentially focused on the general interest or public utility;

It should essentially conduct a socially useful and solidarity-based activity; that is, via its activities, it should aim to provide support to vulnerable groups, combat social exclusion, inequality, and violations of fundamental rights, including at the international level, or to help protect the environment, biodiversity, climate, and natural resources;

It should be subject to at least a partial constraint on profit distribution and to specific rules on the allocation of profits and assets during its entire life, including dissolution. In any case, the majority of the profits made by the undertaking should be reinvested or otherwise used to achieve its social purpose;

It should be governed in accordance with democratic governance models involving employees, customers, and stakeholders affected by its activities; members’ power and weight in decision-making may not be based on the capital they may hold.

And this first recommendation of the Resolution ends by stating that:

The European Parliament considers that nothing prevents conventional undertakings from being awarded the European Social Economy Label if they comply with the abovementioned requirements, particularly regarding their object, the distribution of profits, governance, and decision-making.

What happens is that the rigid conditions that are intended to be required to obtain the European social economy label (with a restricted list of public utility activities or the need for voting at shareholders’ meetings not to be linked to the ownership of share capital) seem designed for the classic organizational forms of the social economy (especially cooperatives), which limits entry into this supposed European category of social economy enterprises to conventional commercial enterprises, as many social enterprises tend to be.

Recently, in December 2021, the European Commission presented an “Action Plan for the social economy -Building an economy that works for people,” which aims to implement concrete measures to help mobilize the full potential of the social economy based on the results of the SBI initiative. This document reflects the relationship, in the opinion of the European Commission, between the social economy and social enterprises:

Traditionally, the term social economy refers to four main types of entities providing goods and services to their members or society at large: cooperatives, mutual benefit societies, associations (including charities), and foundations. However, now, social enterprises are generally understood as part of the social economy. Social enterprises operate by providing goods and services to the market in an entrepreneurial and often innovative fashion, with social and/or environmental objectives as the reasons for their commercial activity. Profits are mainly reinvested to achieve societal objectives. Their method of organization and ownership also follows democratic or participatory principles or focuses on social progress.

As pointed out earlier, on the one hand, there is an undeniable tendency to overcome the initial restriction of the company to specific legal forms (cooperatives, associations, foundations, etc.), and there is a clear recognition of the possibility that any type of private law entity can obtain the status of social enterprise. On the other hand, the European Union itself recommends that social enterprises, in addition to having a purpose oriented toward the general interest or public utility, must meet a series of requirements or conditions in their operation, essentially the priority of reinvesting profits in this objective and management with democratic governance criteria. Thus, it is clear that compliance with these will be easier for entities that are set up using the typical associative formulas of the social economy. In my opinion, the European Union offers member states a flexible scope for the regulation of social enterprises, and at the same time, it is restricted by the principles it imposes as operating features of this type of entity.

3 Models of Legal Regulation of Social Enterprises in Europe

In the European Union, apart from the official documents mentioned above, neither directly applicable regulations nor directives of necessary transposition have been enacted to unify or harmonize the legal status of social enterprises. Hence, there is great freedom in the way in which the member states can regulate these alternative forms of enterprise.Footnote 22 On the one hand, within the aforementioned margin of flexibility, a large number of countries have not issued specific rules for social enterprises, as has occurred in several central and northern European countries (Germany, Austria, the Netherlands, Sweden, etc.). On the other hand, other countries have created specific formulas for social enterprises, and three models of regulation can be distinguished: those that have legally recognized specific organizational figures or legal structures as prototypes of social enterprises, as has occurred in several countries with social cooperatives; those that have enacted a special law to regulate social enterprises; and those that have integrated social enterprises into a general law on the social economy.

Aside from this possible classification of legislative modes, one must consider the existence in Europe of a wide range of legal forms that are considered social enterprises, and the fact that they are legally regulated in the same way (for example, by a special law on social enterprises) or given the same name does not imply that their content is homogeneous in different legal systems. The specific regime for social enterprises in each country depends on a wide variety of national circumstances, such as prevailing political and ideological interests, legal traditions, and pressure from certain business sectors. It is therefore necessary to understand what legal concept of social enterprise exists in each legislation, if any; the legal forms recognized as such; and, in particular, what requirements each of them must meet in order to qualify as social enterprises. An example can clarify this.

Finland was the first country in Europe to regulate social enterprises through a special law (Law 1351/2003), which recognizes that any corporate form can be recognized; thus, the law is very broadly subjective. However, the social purpose of these entities is limited to offering employment opportunities to people with disabilities and the long-term unemployed. Spain, on the other hand, which has no special regulation for social enterprises, regulates social initiative cooperatives in Law 27/1999 on cooperatives. Although it obviously requires these entities to have the legal form of cooperatives and impose certain additional organizational and financial requirements (nonprofit), they can have as their corporate purpose the satisfaction of any social need not met by the market, so the regulation is very broad in this respect. Then one may ask which of these two types of social enterprises (social enterprise proper versus social cooperative) is more social. Well, we will have to go case by case and legislation by legislation to obtain an answer that a priori is not simple. That is why it is so important to undertake, as this book does, a comparative study of social enterprises in different countries around the world.

In this chapter, located in the introductory part of the social enterprise movement and before the part dedicated to the study of the legal situation of social enterprises in different legal systems around the world, it seems interesting to develop in greater detail the aforementioned classification of the different models of legal regulation of social enterprises in Europe and to conclude a table containing the results obtained from the analysis. I have looked into 14 European legal systems that have legally regulated social enterprises.

3.1 Regulating Social Enterprises as Social Cooperatives

The first model of the regulation of social enterprises in Europe corresponds to countries that have regulated them through the creation of a special form of cooperative, the so-called social cooperative. Moreover, this model chronologically emerged earlier in Europe with the enactment in 1991 in Italy of the Disciplina delle cooperative sociali law (1991), a pioneering norm in adapting the legal form of cooperation to the characteristics of social enterprises. The Italian initiative was imitated, with greater and lesser intensity, by other European countries, such as Portugal with the cooperativas de solidariedade social (1997), Spain with the cooperatives of social initiative (1999), France with the société coopérative d’intérêt collectif (2001), Poland (2006), Hungary (2006), Croatia (2011), Greece (2011), and the Czech Republic (2012).Footnote 23

This model is currently no longer in demand since, as we have seen previously, more ambitious perspectives of social enterprises are being imposed in terms of legal entities that can be recognized as such. Surprisingly, however, in Belgium’s 2019 Code des sociétés et des associations, only cooperatives can be legally recognized as social enterprises. It should be recalled that this country was one of the first countries in the world to legally recognize social enterprises through the enactment in 1995 of a law that amended its commercial company law by inserting a section entitled sociétés à finalité sociale and in 1999 became part of the Codes des Societés. With the new code, the concept of a company with a social purpose has been replaced by that of the entreprise sociale. The most striking aspect, as has been pointed out, is that only cooperative companies can be classified as such; therefore, it has been established that within a maximum period of 5 years (until 2024), existing social purpose companies that wish to be recognized as social enterprises must transform themselves into cooperatives.Footnote 24

3.2 Regulation of Social Enterprises by a Special Law

The second model in European comparative law for the regulation of social enterprises, which is clearly growing after the publication of the SBI initiative and with a recognizable influence of other European Union documents on social enterprises that we have mentioned above, corresponds to the countries of the European Union that have regulated them through a special or specific law. Although there are great differences in the requirements that each law demands of an entity to be a social enterprise, they all have one thing in common: they do not create new types of companies but are companies of whatever legal form, including commercial or trading companies, which, if they meet a series of conditions and formally request it, can obtain official recognition as a social enterprise through registration in the corresponding registry. Entities with the status of social enterprises usually obtain privileged tax treatment and are beneficiaries of certain aid packages from public administration authorities.

The European countries that have issued special laws for social enterprises include Finland (2003), the United Kingdom (2005), Slovenia (2011), Denmark (2014), Luxembourg (2016), Italy (2017), Latvia (2017), Slovakia (2018), and Lithuania (2019). As can be seen, some of these countries are of relative economicFootnote 25 importance, but others, such as the United Kingdom and Italy, have a large economic and political dimension. Let us briefly look at some aspects of the legal regime of these two countries to confront two different ways of regulating social enterprises in their content, but not in their form, since both enacted special laws.

The United Kingdom was one of the first European jurisdictions to regulate social enterprises, and it did so in 2005 through the Community Interest Company Regulations 2005. This legal formula, known as CIC, was designed ad hoc so that limited liability companies could conduct activities for the benefit of the community.Footnote 26 Without going into detail in its regulation, the entity in the so-called community interest statement must state that it will conduct its activities for the benefit of the community or a sector thereof and indicate how it intends to do so. The requirements imposed by law on this type of entity are quite light in comparison with other systems. In particular, there are essentially two financial requirements that CICs must meet to ensure that the community will benefit from the main community purpose of the CIC: the existence of certain asset locks, which, if transferred to third parties, must be at market value and, in the event of dissolution, must be allocated to another entity of the same type and have a maximum limit on the distribution of profits to its members. The current number of CICs (close to 19,000) and their spectacular growth in recent yearsFootnote 27 are proof of the undoubted success of this social enterprise model.

In 2017, Italy approved the Codice del Terzo settore, with the aim of systematizing and reorganizing the various entities that make up the third sector in Italy, in which, together with other entities (volunteer organizations, social promotion associations, philanthropic entities, mutual aid societies, and associative networks), social enterprises are included. On the same date as the Codice, a legislative decree of Revisione della disciplina in materia di impresa sociale was approved, repealing the previous law of 2006 on social enterprises, with the intent of making their regime more flexible and regulating tax incentives to contribute to the take-off of the social enterprise in the form of a capital company.Footnote 28 The main requirement for obtaining the legal status of social enterprises in Italy under the new law is that the entity must carry out an entrepreneurial or commercial activity of general interest, a term developed in the law itself with an extensive list of entrepreneurial activities that are presumed to be of this type.

With respect to the conditions required for an entity to be classified as a social enterprise, the primary condition is that it must be nonprofit making, and therefore, as was the case in the previous law, the distribution of profits and surpluses among partners, workers, and managers is prohibited. However, this principle is subject to an important exception, with respect to social enterprises in the form of partnerships, which is a major novelty. In these cases, unlike associations or foundations of social enterprises, dividends may be distributed up to 50% of annualFootnote 29 profits and surpluses. In addition, Italian law establishes other limitations or conditions for social enterprises, such as, among others, that the bylaws must provide for forms of participation in the management of workers, users, and other interested parties, ranging from simple consultation mechanisms to the participation of workers and users in meetings and even, for entities of a certain size, the appointment of a member of the management body. The legal discipline of the societá benefitá (2015) remains in force, with a regime similar to that of benefit corporations in the United States; in Italy, there are several legal avenues for developing social entrepreneurship.Footnote 30

3.3 Regulation of Social Enterprises Within a Social and Solidarity Economy Law

Finally, the other legislative model for regulating social enterprises in the European Union is made up of countries that have regulated the legal status of this type of entity within the framework of a general law on the social and/or solidarity economy. Obviously, for this to happen, it is a requirement that a law of this type exists or is enacted, and this is by no means common in the European Union and only occurs in southern Europe, generally speaking. Spain was a pioneer in the legal recognition of the social economy and in promoting its development as an alternative form of economy (2011), followed by Greece (2011), Portugal (1203), France (2014), Romania (2015), and Greece again (2016), in addition to some countries that have regulated it by regional rules (Belgium and Italy).Footnote 31

Of the five jurisdictions with a state law on social and/or solidarity economy, three have regulated the figure of the social enterprise in this law: France, Romania, and Greece. Again, as in the previous model, the regulations of social enterprises in each of these countries differ significantly. Let us now compare the cases of Greece and France.

In Greece, in 2016, the law on the social and solidarity economy repealed the 2011 law on the social economy and social entrepreneurship, which only recognized social cooperatives as social enterprises. However, legal reform has not meant a general change in orientation with respect to the previous law but an unambitious attempt to give entry to new subjects in the socialFootnote 32 economy. Specifically, in the list of social and solidarity economy entities contained in the law, together with the social cooperative enterprise that was there previously, other types of cooperatives and any other legal entity that has acquired legal personality and meets a series of conditions are included in a new way. However, if you look at the conditions that Greek law imposes on entities that want to be recognized as social enterprises, they are very demanding (essentially decision-making according to the principle of one member one vote, restrictions on the distribution of profits, and significant wage limits for workers), which social cooperatives will find it easier to meet because these requirements are intrinsic to this corporate form.

In France, according to Loi relative à l’économie sociale et solidaire of 2014, the subjects of the social and solidarity economy are both traditional figures of the social economy and commercial companies that, in addition to complying with the conditions of the social and solidarity economy, apply additional management principles (in particular, endowing certain funds and mandatory reserves) and pursue social utility. These entities may qualify as entreprises de l’économie sociale et solidaire, also known as SSE enterprises, and benefit from the rights that are inherent to them, in particular, easy access to financing, tax and public procurement benefits, and visibility as enterprises included in the official lists of enterprises of this type. The law itself makes it possible for a “social and solidarity economy enterprise” to be approved as an entreprise solidaire d’utilité sociale, known by the acronym ESUS, when it cumulatively meets a series of additional requirements (that social utility be the main objective of the entity, demonstrating that its social objective has a significant impact on the income statement, having a limited wage policy, etc.), thus obtaining certain financial advantages.

In 2019, Law No. 2019-486 on the growth and transformation of companies, better known as Pacte Law after the acronym of the action plan in which it originated (Le Plan d’action pour la croissance et la transformation des entreprises), was enacted in France. This law is considered the most important French economic law of the decade and was the result of a major intersectoral growth pact after a long debate. One of the ambitious objectives of the law was to rethink the place of companies in society, and it included measures to promote the development of social activities and purposes by private and commercial enterprises, such as the incorporation of a new form of social enterprise in the Code de Commerce outside the social and solidarity economy law, known as the Société à mission. This can be translated as a company with a mission or purpose and whose regulations bear obvious similarities to the laws on public benefit corporations in the United States. The absence of any reference in the Pacte Law to social and solidarity economy enterprises is evidence of the critical perception of the law by Nicole Notat (President of Vigeo-Eiris, a world leader in environmental, social, and governance analysis, data, and evaluations) and Jean-Dominique Senard (president of the Michelin Group), who were the main authors of the report entitled L’entreprise objet d’intérêt collectif, which gave rise to a new legal regulation. It seems worthwhile to transcribe some of the reflections made by these two well-known French entrepreneurs on the advisability of regulating social enterprise formulas outside the scope of social economy:Footnote 33

The social and solidarity economy statutes present a high degree of exigency that is unsuitable for all business leaders, some of whom wish to remain as close as possible to a traditional commercial enterprise. It must be possible for there to be enterprises registered in a patient economy that are willing to forgo short-term profits to aim at sustainable value creation, without necessarily having cooperative governance or wage oversight.

For its part, Spain is currently studying how to incorporate social enterprises into its legislation, and the most plausible option, although there are doubts as to how to do it, is to amend Law 5/2011 on the Social Economy to broaden the scope of entities that can be considered to form part of the social economy, which is currently limited to the traditional and typical formulas of this type of economy (cooperatives, foundations, labor companies, mutual societies, etc.) and does not include capital companies.Footnote 34 As early as 2009, in one of the proposals for the drafting of the law made by a group of academic experts,Footnote 35 “social enterprises” were included in the list of social economy entities, but this mention was finally excluded from the final text of the 2011 law, apparently due to the lack of foresight and maturity at the time of its concept and delimitation.Footnote 36 Later, the Spanish Social Economy Strategy 2017–2020Footnote 37 regained interest in the possible framing of social enterprises within the framework of the Social Economy Law,Footnote 38 and work is being done along these lines; however, there are still no legislative results.

3.4 Summary Table of the Analysis of European Legal Systems

Next, at the end of this chapter, the results obtained from the comparative law analysis of the laws of 14 countries that regulate social enterprises in the form of a table will be presented. Table 1 shows the basic characteristics and requirements for a company in order to be recognized as a social enterprise in the different legal systems analyzed, and, as can be seen, there has been little uniformity.

Notes

- 1.

For more detail: https://www.rivistaimpresasociale.it/chi-siamo.

- 2.

On these origins of social enterprise in Europe see Defourny and Nyssens (2012), p. 13.

- 3.

For more detail: https://www.emes.net.

- 4.

For which I refer to Borzaga and Defourny (2001).

- 5.

Defourny and Nyssens (2012), p. 15.

- 6.

- 7.

- 8.

Defourny and Nyssens (2012), p. 11.

- 9.

Concept developed in an intense way by Emerson (2003), pp. 35–51 and in later works.

- 10.

Drayton and MacDonald (1993).

- 11.

Yunus (2012), p. 13.

- 12.

COM (2011) 682 final, 25.10.2011.

- 13.

2008/2250(INI). P6TA (2009)0062.

- 14.

SEC (2010) 1564 final.

- 15.

Pp. 6 et seq.

- 16.

(212/C 24/01).

- 17.

(2015/C 419/08).

- 18.

(COM(2013)0083).

- 19.

- 20.

(2014/2236(INI)).

- 21.

(2016/2237(INL)).

- 22.

- 23.

On social enterprises in cooperative form, see Fici (2016-2017), pp. 31–53, and in this publication, see chapter by Hernández, this volume, on social enterprise in the social cooperative form.

- 24.

For more information on the regime of social enterprises in Belgium after the enactment of the Code, see Thierry et al. (2020), p. 98.

- 25.

I will devote a special chapter to the legal regulation of social enterprises in most of these countries at the end of Part III of this study, under the title “Legal Regulation for Social Enterprises in Other European countries”.

- 26.

The history of the origin of the legal figure is very amusingly collected by one of the promoters of the initiative, Lloyd (2011), pp. 31–43, where he explains that the initial name he had thought of was Public Interest Company (PIC) with the idea of showing that the interest of the companies was not private but that with those same initials at that time there was a ministerial project underway and so they had to change the name to CIC.

- 27.

Which has been spectacular in 2020 with a 20% increase over the previous year with the approval of some 5000 new CICs Data obtained from Regulator CIC (2020).

- 28.

- 29.

- 30.

On the content of this rule, see Ventura (2016), pp. 1134–1167.

- 31.

In Hiez (2021), pp. 46 and 47, with a map showing the countries in Europe that have enacted a social and solidarity economy law and those that have a draft law; and on pp. 30 and 31 the world map, which shows a growth in the number of laws and draft laws on social economy in Latin America and Africa.

- 32.

Fajardo and Frantzeskaki (2017), pp. 50 et seq.

- 33.

Notat and Senard (2018), pp. 8–9.

- 34.

- 35.

Available in Monzón et al. (2009).

- 36.

Fajardo (2018), pp. 119 et seq.

- 37.

Approved by Resolution of 15 March 2018 of the Secretary of State for Employment.

- 38.

Measure No. 14: ‘Study of the concept of social enterprise in the Spanish framework and analysis of its possible relationship with the concepts of social enterprise at the European level. The possible implications of the recognition of the concept of social enterprise as defined by the “Social Business Initiative” (Initiative in favor of Social Entrepreneurship) and its framework, if applicable, within the framework of Law 5/2011, on Social Economy, will be analyzed’.

References

Atzela I (2020) Un marco jurídico para la empresa social en la Unión Europea, CIRIEC-España. Revista Jurídica de Economía Social y Cooperativa 37:105–140

Austin J, Ezequiel R (2009) Corporate social entrepreneurship. Harvard Business School Working Paper 09:101, 1–7

Borzaga C, Defourny J (2001) The emergence of social enterprise. Routledge, London

Borzaga C, Galera G, Franchini B, Chiomento S, Nogales R, Carini C (2020) European Commission–social enterprises and their ecosystems in Europe. Comparative synthesis reports. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg. https://europa.eu/!Qq64ny

Campos V (2016) La economía social y solidaria en el siglo XXI: un concepto en evolución. Cooperativas, B corporations y economía del bien común. Oikonomics: revista de economía, empresa y sociedad 6:6–15

Chaves R, Monzón JL (2018) La economía social ante los paradigmas económicos emergentes: innovación social, economía colaborativa, economía circular, responsabilidad social empresarial, economía del bien común, empresa social y economía solidaria. CIRIEC-España. Revista economía pública, social y cooperative 93:5–50

Dees G, Anderson BB (2006) Framing a theory of social entrepreneurship: Building on two schools of practice and thought. In: Mosher-Williams R (ed) Research on social entrepreneurship: understanding and contributing to an emerging field. Arnova, Washington D.C.

Dees G (1998) The meaning of social entrepreneurship. Comments and suggestions contributed by the Social Entrepreneurship Funders Working Group. Harvard Business School, Boston

Defourny J, Nyssens M (2010) Conceptions of social enterprise and social entrepreneurship in Europe and the United States: convergences and divergences. J Soc Entrepren 1:32–53

Defourny J, Nyssens M (2012) El enfoque EMES de empresa social desde una perspectiva comparada. CIRIEC-España. Revista de economía pública, social y cooperativa 75:7–34

Drayton W, MacDonald S (1993) Leading public entrepreneurs. Ashoka, Arlington

Emerson J (2003) The blended value proposition: integrating social and financial returns. Calif Manag Rev 4(45):35–51

Fajardo G, Frantzeskaki M (2017) La economía social y solidaria en Grecia. Marco jurídico, entidades y principales características. REVESCO, Revista de Estudios Cooperativos 25:49–88

Fajardo G (2018) La identificación de las empresas de economía social en España. Problemática jurídica. REVESCO, Revista de Estudios Cooperativos 128:99–126

Fici A (2020a) La empresa social italiana después de la reforma del tercer sector. CIRIEC-España. Revista jurídica de economía social y cooperativa 36:177–193

Fici A (2016) Social enterprise in cooperative form. Cooperativismo e economía social 39:31–53

Fici A (2015) Recognition and legal forms of social enterprise in Europe: a critical analysis from a comparative law perspective. Euricse, Trento

Fici A (2020b) Social enterprise laws in Europe after the 2011 “Social Business Initiative”. Comparative analysis from the perspective of workers and social cooperatives. CECOP, Brussels

Hiez D (2021) Guide pour la rédaction d’un droit de l’économie Sociale et Solidaire. ESS Forum International

Lloyd S (2011) Transcript: creating the CIC. Vermont Law Rev 35:31–43

Monzón JL, Calvo R, Chaves R, Fajardo G, Valdes Dal-Ré F (2009) Informe para la elaboración de una Ley de fomento de la Economía Social. http://observatorioeconomiasocial.es/media/archivos/Informe_CIRIEC_Ley_Economia_Social.pdf

Notat N, Senard JD (2018) L’entreprise objet d’intérêt collectif, Raport aux ministère de la Transition écologique et solidaire/ministère de la Justice/ministère de l’Économie et des Finances/ministère du Travail. Available at: Regulator CIC: The Office of the Regulator of Community Interest Companies annual report 2019 to 2020. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/cic-regulator-annual-report-2019-to-2020

Thierry T, Delcorde JA, Barnaerts M (2020) A new paradigm for cooperative societies under the new Belgian code of companies and associations. Int J Cooperative Law 3:98–112

Vargas Vasserot C (2021) Las empresas sociales. Regulación en Derecho comparado y propuestas de lege ferenda para España. Revista del Ministerio de Trabajo y Economía Social 150:63–86

Ventura L (2016) Benefit corporation e circolazione di modelli: le “società benefit”, un trapianto necessario? Contratto e impresa 32:1134–1167

Young D (1986) Entrepreneurship and the behavior of nonprofit organizations: elements of a theory. In: Rose Ackerman S (ed) The economics of non-profit institutions. Oxford University Press, New York

Yunus M (2012) Building social business: the new kind of capitalism that serves humanity’s most pressing needs. Public Affairs, New York

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Vargas Vasserot, C. (2023). Social Enterprises in the European Union: Gradual Recognition of Their Importance and Models of Legal Regulation. In: Peter, H., Vargas Vasserot, C., Alcalde Silva, J. (eds) The International Handbook of Social Enterprise Law . Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-14216-1_3

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-14216-1_3

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-14215-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-14216-1

eBook Packages: Law and CriminologyLaw and Criminology (R0)