Abstract

There is a general lack of information on the impact of forest plantations and the presence of urban settlements on populations of resource-demanding species such as large felids. To partially address this problem, a project study was conducted to find out whether mosaics of forest plantations and native vegetation can function as an adequate habitat for pumas (Puma concolor) in southern Brazil. The study was conducted within a 1255-km2 area, managed for planted stands of Pinus spp. and Eucalyptus spp. Individual identification of pumas was carried out using a combination of track-matching analysis (discriminant analysis) and camera-trapping. Both techniques recorded closely similar numbers of individual pumas, either total (9–10 individuals) or resident (5–6 individuals). A new approach, developed during this study, was used to individualize pumas by their markings around the muzzle. The estimated density varied from 6.2 to 6.9 individuals/100 km2, ranking among the highest across the entire puma range and indicating a potential total population of up to 87 individuals in the study site. In spite of the availability of extensive areas without human disturbance, a radio-tracked female used a core home range that included forest plantations, an urbanized village, and a two-lane paved road with regular vehicular traffic. The high density of pumas and the species’ intensive use of modified landscapes are interpreted here as deriving from conditions rarely found near human settlements: mutual tolerance by pumas and humans and an adequate habitat (regardless of plantations) largely due to the inhibition of invasions and hunting and maintenance of sizable extents of native forest patches. More widely, it suggests the potential of careful management in forestry operations to provide habitat conditions for resource-demanding species such as the puma. Furthermore, it highlights the importance of curbing invasions and hunting, in this case provided by the presence of company employees, for the maintenance of wildlife populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Athreya V, Belsare A (2006) ‘Carnivore Conflict’: support provided to leopards involved in conflict-related cases in Maharashtra. Wildlife Trust of India, New Delhi

Bacha CJC, Barros ALM (2004) Reflorestamento no Brasil: evolução recente e perspectivas para o futuro. Scientia Forestalis 66:191–203

Beier P (1991) Cougar attacks on humans in the United States and Canada. Wildlife Society Bulletin 19:403–412

Beier P (1995) Dispersal of juvenile cougars in fragmented habitat. Journal of Wildlife Management 59:228–237

Belden RC, Frankenberger WB, McBride RT, Schwikert ST (1988) Panther habitat use in southern Florida. Journal of Wildlife Management 52:660–663

Carroll C, Noss RF, Paquet PC (2000) Carnivores as focal species for conservation in the rocky mountain region. Ecological Applications 11:961–980

Chiarello AG (2000) Conservation value of a native forest fragment in a region of extensive agriculture. Revista Brasileira de Biologia 60(2):37–247

Child G (1995) Wildlife and people: the Zimbabwean success. How conflict between animals and people became progress for both. Wisconsin Foundation, New York

Comiskey EJ, Bass OL Jr, Gross LJ, McBride RT, Salinas R (2002) Panthers and forests in South Florida: an ecological perspective. Conservation Ecology 6:18. Available from http://www.consecol.org/vol6/iss1/art18

Cullen L Jr, Bodmer RE, Pádua CV (2000) Effects of hunting in habitat fragments of the Atlantic forests, Brazil. Biological Conservation 95:49–56

ECE/FAO (2000) Forest products annual review (1999)–(2000) Timber Bulletin Vol. LIII. UN/ECE Timber Committee

Eisenberg JF (1980) The density and biomass of tropical mammals. In: Soulé ME, Wilcox BA (eds) Conservation biology: an evolutionary perspective. Sinauer, Sunderland, MA, pp 35–55

Emmons LH (1987) Comparative feeding ecology of felids in a neotropical rainforest. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 20:271–283

Evans J (1999) Planted forests of the wet and dry tropics: their variety, nature, and significance. New Forests 17:1–3

Fitzhugh EL, Gorenzel WP (1985) Design and analysis of mountain lion track surveys. In: Laudenslayer WF Jr (ed) Cal-Neva wildlife. Western Section, The Wildlife Society, California, pp 78–87

Fjelline DP, Mansfield TM (1989) Method to standardize the procedure for measuring mountain lion tracks. In: Smith RH (ed) Proceedings of the Third Mountain Lion Workshop, Prescott, AZ, pp 49–51

Frankel OH (1983) The place of management and conservation. In: Schonewald-Cox C, Chambers SM, Bruce M, Lawrence T (eds) Genetics and conservation: a reference for managing wild animal populations. Benjamin/Cummings, New York, pp 1–13

Franklin WL, Johnson WE, Sarno RJ, Iriarte JA (1999) Ecology of the Patagonia puma Felis concolor patagonica in southern Chile. Biological Conservation 90:33–40

Gay SW, Best TL (1996) Age-related variation in skulls of the puma (Puma concolor). Journal of Mammalogy 77:191–198

Grigione MM, Burman P, Bleich VC, Pierce BM (1999) Identifying individual mountain lions Felis concolor by their tracks: refinement of an innovative technique. Biological Conservation 88:25–32

Harvey MJ, Barbour RW (1965) Home range of Microtus ochrogaster as determined by a modified minimum area method. Journal of Mammalogy 46:398–402

IBGE (1992) Guia da vegetação brasileira. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

IUCN (1990) Our common future. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland

Karanth KU, Nichols JD (1998) Estimation of tiger densities in India using photographic captures and recaptures. Ecology 79:2852–2862

Karanth KU, Sunquist ME (1992) Population structure, density and biomass of large herbivores in the tropical forests of Nagarahole, India. Journal of Tropical Ecology 8:21–35

Karanth KU, Nichols JD, Kumar NS (2004a) Photographic sampling of elusive mammals in tropical forests. In: Thompson WL (ed) Sampling rare or elusive species: concepts and techniques for estimating population parameters. Island Press, Washington, DC, pp 229–247

Karanth KU, Nichols JD, Kumar NS, Link WA, Hines JE (2004b) Tigers and their prey: predicting carnivore densities from prey abundance. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS) 101(14):4854–4858

Kawanishi K, Sunquist ME (2004) Conservation status of tigers in a primary rainforest of Peninsular Malaysia. Biological Conservation 120:329–344

Kelly MJ, Noss AJ, di Bitetti MS, Maffei L, Arispe RL, Paviolo A, de Angelo CD, di Blanco YE (2008) Estimating puma densities from camera trapping across three study sites: Bolivia, Argentina, and Belize. Journal of Mammalogy 89(2):408–418

Kenward R, Hodder KH (1995) Ranges V. An analysis system for biological location data. Institute of Terrestrial Ecology, Furzebrook Research Station, Wareham, Dorset, UK

Lewison R, Fitzhugh EL, Galentine SP (2001) Validation of a rigorous track classification technique: identifying individual mountain lions. Biological Conservation 99(3):313–321

Mac Nab BK (1963) Bioenergetics and the determination of home range size. American Naturalist XCVII(894):133–140

Maehr DS (1990) The Florida panther and private lands. Conservation Biology 4:167–170

Maffei L, Noss AJ (2008) How small is too small? Camera trap survey areas and density estimates for ocelots in the Bolivian Chaco. Biotropica 40:71–75

Maffei L, Cuéllar E, Noss A (2004) One thousand jaguars (Panthera onca) in Bolivia’s Chaco? Camera trapping in the Kaa-Iya National Park. Journal of Zoology (London) 262:295–304

Mäher JKF Jr, Schneider M (2003) Ungulados. In: Fontana CS, Bencke GA, Reis RE (eds) Livro Vermelho da Fauna Ameaçada de Extinção no Rio Grande do Sul. Edipucrs, Porto Alegre, Brazil, pp 547–565

Mazzolli M (2000) A comparison of habitat use by the mountain lion (Puma concolor) and kodkod (Oncifelis guina) in the southern Neotropics with implications for the assessment of their vulnerability status. MSc thesis, University of Durham, Durham, UK

Mazzolli M (2005) Avaliando integridade ambiental e predizendo extinções locais a partir de padrões de desaparecimento da mega-mastofauna atual do sul do Brasil. Proceeding of the III Congresso Brasileiro de Mastozoologia. Aracruz, ES. Sociedade Brasileira de Mastozoologia/UFES, 12–16 October, p 111

Mazzolli M (2006) Persistência e riqueza de mamíferos focais em sistemas agropecuários no planalto meridional. PhD Thesis, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS), Porto Alegre, Brazil

Mazzolli M (2007) Projeto Puma: studying and conserving puma and jaguar in Brazil. Wild Felid Monitor 1(1):15

Mazzolli M (2009) Mountain lion Puma concolor attacks on a maned wolf Chrysocyon brachyurus and a domestic dog in a forestry system. Mastozoologia Neotropical 16(2):465–470

Mazzolli M, Graipel ME, Dunstone N (2002) Mountain lion depredation in southern Brazil. Biological Conservation 105:43–51

Michalski F, Boulhosa RLP, Faria A, Peres CA (2006) Human-wildlife conflicts in a fragmented Amazonian forest landscape: determinants of large felid depredation on livestock. Animal Conservation 9:179–188

Mishra C (1997) Livestock depredation by large carnivores in the Indian trans-Himalaya: conflict perceptions and conservation prospects. Environmental Conservation 24:338–343

Neu CW, Byers CR, Peek JM (1974) A technique for analysis of utilization: availability data. Journal of Wildlife Management 38(3):541–545

Norton P (1984) Leopard conservation in South Africa. African Wildlife 38:191–196

Norton PM, Henley SR (1987) Home range and movements of male leopards in the Cedarberg Wilderness Area, Cape Province. South African Journal of Wildlife Research 17:41–48

Nowell K, Jackson P (1996) Status, survey and conservation action plan, wild cats. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland

Nyhus PJ, Tilson R (2004) Characterizing human–tiger conflict in Sumatra, Indonesia: implications for conservation. Oryx 38:68–74

Oli MK, Taylor IR, Rogers ME (1994) Snow leopard (Panthera uncia) predation of livestock: an assessment of local perceptions in the Annapurna Conservation Area, Nepal. Biological Conservation 68:63–68

Otis DL, Burnham KP, White GC, Anderson DR (1978) Statistical inference from capture data on closed animal populations. Wildlife Monographs 62, The Wildlife Society, Lawrence, KS

Palmberg-Lerche C, Iversen PA, Sigaud P (2002) Forest genetic resources. Forest Genetic Resources Bulletin 29. FAO, Rome

Palmeira FBL, W Barrella (2007) Conflicts caused by predation on domestic livestock by large cats in quilombola communities in the Atlantic Forest. Biota Neotropical 7 (online). Available from http://www.scielo.br

Peres CA (1996) Population status of white-lipped Tayassu pecari and collared peccaries T. tajacu in hunted and unhunted Amazonian forests. Biological Conservation 77:115–123

Pierce BM, Bleich VC, Wehausen JD, Bowyer RT (1999) Migratory patterns of mountain lions: implications for social regulation and conservation. Journal of Mammalogy 80(3):986–992

Pillar VD, Boldrini II, Hasenack H, Jacques AVA, Both R, Müller SC, Eggers L, Fidelis A, Santos MMG, Oliveira JM, Cerveira J, Blanco C, Joner F, Cordeiro JL, Pinillos Galindo M (2006) Workshop “Estado atual e desafios para a conservação dos campos.” Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS), Porto Alegre, Brazil. Available from http://ecoqua.ecologia.ufrgs.br. Accessed 14 July 2007

Quigley HB, Crawshaw PG Jr (1992) A conservation plan for the jaguar Panthera onca in the Pantanal region of Brazil. Biological Conservation 61:149–157

Rabinowitz AR (1986) Jaguar predation on domestic livestock in Belize. Wildlife Society Bulletin 14:170–174

Rextad E, Burnham KP (1991) User’s guide for interactive program CAPTURE. Abundance estimation of closed animal populations. Colorado State University, Boulder

Riley SJ, Malecki RA (2001) A landscape analysis of cougar distribution and abundance in Montana, USA. Environmental Management 28:317–323

Robinson JG, Redford KH (1986) Body size, diet, and population density of neotropical forest mammals. American Naturalist 128(5):665–680

Safford HD (1999) Brazilian Páramos I. An introduction to the physical environments and vegetation of the campos de altitude. Journal of Biogeography 26:693–712

Schaller GB (1972) The Serengeti lion, a study of predator–prey relations. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Schaller GB (1983) Mammals and their biomass on a Brazilian ranch. Arquivos de Zoologia 31:1–36

Seidensticker J, Sunquist ME, McDougal C (1990) Leopards living at the edge of the Royal Chitwan National Park Nepal. In: Daniel JC, Serrao JS (eds) Conservation in developing countries: problems and prospects. Proceedings of the centenary seminar of the Bombay Natural History Society. Bombay Natural History Society and Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 415–423

Silveira L (2004) Ecologia comparada e conservação da onça-pintada (Panthera onca) e onça-parda (Puma concolor) no cerrado e pantanal. PhD thesis, Universidade de Brasília

Silver SC, Ostro LET, Marsh LK, Maffei L, Noss AJ, Kelly MJ, Wallace RB, Gómez H, Ayala G (2004) The use of camera traps for estimating jaguar Panthera onca abundance and density using capture/recapture analysis. Oryx 38(2):148–154

Smallwood KS, Fitzhugh EL (1993) A rigorous technique for identifying individual mountain lions Felis concolor by their tracks. Biological Conservation 65:51–59

Smallwood KS, Schonewald C (1998) Study design and interpretation of mammalian carnivore density estimates. Oecologia 113:474–491

Soisalo MK, Cavalcanti SMC (2006) Estimating the density of a jaguar population in the Brazilian Pantanal using camera-traps and capture–recapture sampling in combination with GPS radio-telemetry. Biological Conservation 129:487–496

Spalton JA, al Hikmani HM, Willis D, Said ASB (2006) Critically Endangered Arabian leopards Panthera pardus nimr persist in the Jabal Samhan Nature Reserve, Oman. Oryx 40(3):287–294

Stickel LF (1954) A comparison of certain methods of measuring ranges of small mammals. Journal of Mammalogy 35:1–15

Taylor VJ, Dunstone N (1996) The exploitation of mammal populations. Chapman & Hall, London

Trolle M, Noss AJ, Lima E de S, Dalponte JC (2007) Camera-trap studies of maned wolf density in the Cerrado and the Pantanal of Brazil. Biodiversity and Conservation 16:1197–1204

Wallace RB, Gomez H, Ayala G, Espinoza F (2003) Camera trapping for jaguar (Panthera onca) in the Tuichi Valley, Bolivia. Mastozoologia Neotropical 10:133–139

White GC, Garrot RA (1990) Analysis of wildlife radio-tracking data. Academic Press, San Diego, CA

Wiegand T, Moloney KA, Naves J, Knauer F (1999) Finding the missing link between landscape structure and population dynamics: a spatially explicit perspective. American Naturalist 154:605–627

Worton BJ (1989) Comparison of several probabilistic home-range models. Journal of Wildlife Management 39:118–123

WWF(Wildlife Fund for Nature) (1996) Forests for life: The WWF/IUCN forest policy book. WWF, Godalming, UK

Acknowledgements

I am indebted to Marcella J. Kelly for her invaluable help in improving the manuscript and to Laurence Mackin for spell-check and grammar corrections. In chronological order, the project started with the commitment from the Klabin Paper Company in southern Brazil to support research on its land. Several persons were involved at this stage. Ralf Andreas Berndt gave initial support for the project. Paulo Kikuti and other executive directors, including Raul M. Speltz, approved and supported the project during the course of the study. The Park staff provided help with traps, including Sérgio A. Filipak, Alceu B. Mello, Lauredi J. Mello, Donizete L. Bueno, Anastácio T. de Oliveira, and Eliane F. Leite. GIS maps of the study area were kindly provided by Nilton L. Venturi. Eliane F. Young Blood helped with the company’s library. Assistance in data collection and veterinarian support was provided by Catherine B. Ryan. Many memorable moments were spent on the trail accompanied by my very enthusiastic 3-year old-daughter Kimberly. Part of the analysis in this article was conducted in the United Kingom when I was writing my MSc thesis. The UK Foreign Office and the British Council provided me with a Chevening scholarship, and I am particularly grateful to Ann Lipe and Judith Elliot of the UK British Council. I am also indebted to my then supervisor, Dr. Nigel Dunstone, for helping me with the thesis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1

Tables with classification results from discriminant analysis of puma tracks for each paw (right front, left front, right hind, left hind). Groups are in rows and predicted groups are in columns. Track sets that rated above 75% were assigned to their own group. The remaining track sets were combined with other groups according to predicted values in columns.

Groups | Predicted groups | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

3 | 4 | 9 | 12 | 14 | 19 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 31 | N | |

Right front | |||||||||||

3 | 71,43 | 0 | 0 | 28,57 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

4 | 0 | 90 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 |

9 | 10 | 0 | 80 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 |

12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 80 | 0 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

19 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 60 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 0 | 5 |

27 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 33,33 | 66,67 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

28 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 0 | 80 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

29 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 50 | 0 | 4 |

31 | 0 | 0 | 16,67 | 0 | 16,67 | 0 | 0 | 16,67 | 0 | 50 | 6 |

Groups | Predicted groups | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

3 | 4 | 5 | 9 | 12 | 13 | 28 | 29 | N | |

Left front | |||||||||

3 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 |

4 | 0 | 92,31 | 0 | 0 | 7,69 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13 |

5 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 25 | 25 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 77,78 | 22,22 | 0 | 0 | 9 |

13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 33,33 | 0 | 66,67 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

28 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 5 |

29 | 0 | 0 | 33,33 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 66,67 | 3 |

Groups | Predicted groups | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 9 | 12 | 28 | 29 | 31 | N | |

Right hind | ||||||||||

1 | 80 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 5 |

2 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

3 | 0 | 0 | 83,33 | 0 | 0 | 16,67 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 90 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 |

9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 75 | 25 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 |

12 | 0 | 0 | 14,29 | 0 | 14,29 | 42,86 | 28,57 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

28 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 80 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

29 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 60 | 0 | 5 |

31 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 75 | 4 |

Groups | Predicted groups | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1 | 3 | 4 | 9 | 10 | 12 | 28 | 29 | 36 | |

Left hind | |||||||||

1 | 80 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

3 | 0 | 66,67 | 0 | 16,67 | 0 | 16,67 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

4 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 85,71 | 14,29 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 80 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

12 | 0 | 22,22 | 0 | 11,11 | 0 | 66,67 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

28 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

29 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 83,33 | 0 |

Appendix 2

Statistics of habitat use by forest cover, using χ2 and Bonferroni (α = 0.10) intervals of confidence. Habitats are native vegetation (forest predominant) and plantations of pinus, eucalyptus, and araucaria. The proportion of available area (pi 0) is compared with the theoretical proportion of occurrence (pi) to determine if the hypothesis is accepted or rejected, (i.e., pi = pi 0). If pi 0 > pi, the species is using the habitat (k) less than expected; if pi 0 < pi, it is using the habitat more than expected.

Species | Habitat (k) | Proportion of available area (pi 0) | No. observed | No. expected | χ2 | Proportion observed in each area (pi) | Confidence interval on proportion of occurrence (pi) | Habitat selection |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Capybara (groups) | ||||||||

Native vegetation | 0.41 | 13 | 11 | 0 | 0.46 | 0.35 ≤ p 1 ≤ 0.58 | = | |

Pinus | 0.37 | 14 | 10 | 1 | 0.50 | 0.39 ≤ p 2 ≤ 0.61 | + | |

Eucalyptus | 0.16 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 0.04 | 0.00 ≤ p 3 ≤ 0.08 | − | |

Araucaria | 0.07 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0.00 | 0.00 ≤ p 4 ≤ 0.17 | = | |

Coati (groups) | ||||||||

Native vegetation | 0.41 | 103 | 125 | 4 | 0.34 | 0.30 ≤ p 5 ≤ 0.37 | − | |

Pinus | 0.37 | 153 | 112 | 15 | 0.50 | 0.46 ≤ p 6 ≤ 0.53 | + | |

Eucalyptus | 0.16 | 38 | 48 | 2 | 0.12 | 0.10 ≤ p 7 ≤ 0.15 | − | |

Araucaria | 0.07 | 13 | 20 | 3 | 0.04 | 0.03 ≤ p 8 ≤ 0.06 | − | |

Collared peccary (groups) | ||||||||

Native vegetation | 0.41 | 153 | 198 | 10 | 0.32 | 0.29 ≤ p 9 ≤ 0.34 | − | |

Pinus | 0.37 | 225 | 178 | 13 | 0.46 | 0.44 ≤ p 10 ≤ 0.49 | + | |

Eucalyptus | 0.16 | 64 | 75 | 2 | 0.13 | 0.11 ≤ p 11 ≤ 0.15 | − | |

Araucaria | 0.07 | 43 | 32 | 4 | 0.09 | 0.07 ≤ p 12 ≤ 0.10 | = | |

Grey brocket deer | ||||||||

Native vegetation | 0.41 | 104 | 402 | 221 | 0.11 | 0.09 ≤ p 13 ≤ 0.12 | − | |

Pinus | 0.37 | 495 | 355 | 50 | 0.50 | 0.48 ≤ p 14 ≤ 0.52 | + | |

Eucalyptus | 0.16 | 304 | 153 | 150 | 0.31 | 0.29 ≤ p 15 ≤ 0.33 | + | |

Araucaria | 0.07 | 83 | 80 | 5 | 0.08 | 0.07 ≤ p 16 ≤ 0.09 | = | |

Nine-banded armadillo | ||||||||

Native vegetation | 0.41 | 22 | 35 | 5 | 0.20 | 0.20 ≤ p 17 ≤ 0.31 | − | |

Pinus | 0.37 | 42 | 31 | 4 | 0.43 | 0.43 ≤ p 18 ≤ 0.56 | + | |

Eucalyptus | 0.16 | 14 | 13 | 0.05 | 0.12 | 0.12 ≤ p 19 ≤ 0.21 | = | |

Araucaria | 0.07 | 7 | 6 | 0.34 | 0.05 | 0.05 ≤ p 20 ≤ 0.12 | = | |

Prehensile-tailed porcupine | ||||||||

Native vegetation | 0.41 | 11 | 13 | 0 | 0.33 | 0.24 ≤ p 21 ≤ 0.43 | = | |

Pinus | 0.37 | 15 | 12 | 1 | 0.45 | 0.35 ≤ p 22 ≤ 0.56 | = | |

Eucalyptus | 0.16 | 6 | 5 | 0 | 0.18 | 0.10 ≤ p 23 ≤ 0.26 | = | |

Araucaria | 0.07 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0.03 | 0.00 ≤ p 24 ≤ 0.07 | = | |

White-lipped peccary (groups) | ||||||||

Native vegetation | 0.41 | 92 | 116 | 5 | 0.32 | 0.29 ≤ p 25 ≤ 0.36 | – | |

Pinus | 0.37 | 101 | 104 | 0 | 0.36 | 0.32 ≤ p 26 ≤ 0.39 | = | |

Eucalyptus | 0.16 | 51 | 44 | 1 | 0.15 | 0.03 ≤ p 27 ≤ 0.21 | = | |

Araucaria | 0.07 | 40 | 19 | 24 | 0.14 | 0.12 ≤ p 28 ≤ 0.17 | + | |

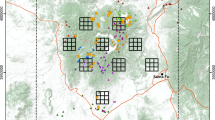

Statistics of habitat use by blocks, using χ2 and Bonferroni (α = 0.10) intervals of confidence. Block 1 contained 60–69% of natural forest, block 2 contained 50–59%, block 3 contained 40–49%, and block 4 contained only 20–39% natural forest. The proportion of available area (pi 0) is compared with the theoretical proportion of occurrence (pi) to determine if the hypothesis is accepted or rejected (i.e., pi = pi 0). If pi 0 > pi, the species is using the blocks (k) less than expected; if pi 0 < pi, it is using more than expected.

Species | Habitat (k) | Proportion of available area (pi 0) | No. observed | No. expected | χ2 | Proportion observed in each area (pi) | Confidence interval on proportion of occurrence (pi) | Habitat selection |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Capybara (groups) | ||||||||

Block 1 | 0.23 | 17 | 5 | 26 | 0.74 | 0.35 ≤ p 1 ≤ 0.58 | + | |

Block 2 | 0.40 | 6 | 9 | 1 | 0.26 | 0.39 ≤ p 2 ≤ 0.61 | = | |

Block 4 | 0.37 | 0 | 9 | 9 | 0.00 | 0.00 ≤ p 3 ≤ 0.08 | − | |

Coati (groups) | ||||||||

Block 1 | 0.23 | 45 | 29 | 9 | 0.36 | 0.27 ≤ p 4 ≤ 0.44 | + | |

Block 2 | 0.40 | 57 | 50 | 1 | 0.45 | 0.36 ≤ p 5 ≤ 0.54 | = | |

Block 4 | 0.37 | 24 | 47 | 11 | 0.19 | 0.12 ≤ p 6 ≤ 0.26 | − | |

Collared peccary (groups) | ||||||||

Block 1 | 0.23 | 53 | 42 | 3 | 0.29 | 0.25 ≤ p 7 ≤ 0.32 | + | |

Block 2 | 0.40 | 36 | 74 | 19 | 0.20 | 0.17 ≤ p 8 ≤ 0.22 | − | |

Block 4 | 0.37 | 95 | 68 | 10 | 0.52 | 0.48 ≤ p 9 ≤ 0.55 | + | |

Grey brocket deer | ||||||||

Block 1 | 0.23 | 116 | 102 | 2 | 0.26 | 0.24 ≤ p 10 ≤ 0.28 | = | |

Block 2 | 0.40 | 175 | 178 | 0 | 0.39 | 0.37 ≤ p 11 ≤ 0.42 | = | |

Block 4 | 0.37 | 155 | 165 | 1 | 0.35 | 0.32 ≤ p 12 ≤ 0.37 | = | |

Nine-banded armadillo | ||||||||

Block 1 | 0.23 | 10 | 5 | 5 | 0.45 | 0.35 ≤ p 17 ≤ 0.56 | + | |

Block 2 | 0.40 | 11 | 9 | 1 | 0.50 | 0.39 ≤ p 18 ≤ 0.61 | = | |

Block 4 | 0.37 | 1 | 8 | 6 | 0.05 | 0.00 ≤ p 19 ≤ 0.09 | − | |

Prehensile-tailed porcupine | ||||||||

Block 1 and 2 | 0.52 | 8 | 9 | 0 | 0.47 | 0.35 ≤ p 20 ≤ 0.59 | = | |

Block 3 and 4 | 0.48 | 9 | 8 | 0 | 0.53 | 0.41 ≤ p 21 ≤ 0.65 | = | |

White-lipped peccary (groups) | ||||||||

Block 1 | 0.23 | 33 | 22 | 5 | 0.14 | 0.11 ≤ p 22 ≤ 0.17 | = | |

Block 2 | 0.40 | 42 | 38 | 0 | 0.18 | 0.15 ≤ p 23 ≤ 0.21 | = | |

Block 4 | 0.37 | 43 | 36 | 1 | 0.15 | 0.18 ≤ p 24 ≤ 0.21 | + | |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mazzolli, M. Mosaics of Exotic Forest Plantations and Native Forests as Habitat of Pumas. Environmental Management 46, 237–253 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-010-9528-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-010-9528-9