Abstract

Reversing land degradation and achieving ecosystem restoration and management are routes to climate change adaptation and mitigation. The financial resources to achieve this are increasingly available. A major challenge is the absence of scalable mechanisms that can incentivize rapid change for rural communities at the decade-long time scale needed to respond to the climate emergency. Despite moves toward inclusive green finance (IGF), a major structural gap remains between the funding available and the unbankable small-scale producers who are stewards of ecosystems. This chapter reports on inclusive finance that can help fill this gap and incentivizes improved ecosystem stewardship, productivity, and wealth creation. A key feature is the concept of eco-credit to build ecosystem management and restorative behaviors into loan terms. Eco-credit provides an approach for overcoming income inequality within communities to enhance the community-level ecosystem governance and stewardship. The paper discusses the experience of implementing the Community Environment Conservation Fund (CECF) over a 8-year-period from 2012. The CECF addresses the unbankable 80% of community members who cannot access commercial loans, has c. 20,000 users in Uganda and pilots in Malawi, Kenya, and Tanzania. The model is contextualized alongside complementary mechanisms that can also incentivize improved ecosystem governance as well as engage and align communities, government, development partners, and the private sector. This complementary infrastructure includes commercial eco-credit as exemplified by the Climate Smart Lending Platform, and the community finance of the Village Savings and Loans Associations (VSLA) model upon which CECF builds. The paper describes the technologies and climate finance necessary for significant scale-up.

This chapter was previously published non-open access with exclusive rights reserved by the Publisher. It has been changed retrospectively to open access under a CC BY 4.0 license and the copyright holder is “The Author(s)”. For further details, please see the license information at the end of the chapter.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download reference work entry PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Climate change adaptation

- Mitigation

- East Africa

- Ecosystems governance

- Inclusive finance

- Nature-based solutions

- Technology

- Land degradation neutrality

- Forest landscape restoration

- Incentive mechanism

Introduction

The objectives of this chapter are to (a) provide a background to the need for community-level inclusive finance to incentivize change adaptation and mitigation, (b) outline the concept of eco-credit, (c) describe an operational model of community eco-credit that shows promise to incentivize ecosystem management, climate change adaptation, and mitigation as well as disaster resilience building at the community level, and (d) place this model in a framework of complementary allied approaches. The paper also discusses the potential for scale-up and makes recommendations for future work. The paper is written by the innovators, designers, and implementers of the model over its 8-year development period (staff of the International Union for Conservation of Nature) and a group that have independently reviewed the approach (Ellis-Jones et al. 2018), and who are also designing the web-based and mobile-phone technology tools and models to support its scale-up (GreenFi Systems Ltd, a social enterprise). The paper’s focus is ecosystem or landscape conservation, management, and restoration, but the model can include other environmentally positive actions.

The approach has been subject to a number of reviews including Kakuru and Masiga (2016), Ellis-Jones et al. (2018), World Bank (2017), Mott MacDonald (2018a, b), Roberts (2017), and Wild (2019). A limitation of the program was that the reviews indicated weaknesses in monitoring component with the absence of an impact monitoring protocol in the IUCN CECF Guidelines (IUCN 2013), particularly for assessing verified environmental and social impact. This monitoring protocol needs addressing in the main pilot location and warrants further research and development.

The Need for Green Community-Level Inclusive Finance to Meet the SDGs

Ecosystem Restoration and Management as a Route to Climate Adaptation and Mitigation

Land and ecosystem degradation is now considered to affect almost 25% of the world’s land area causing a loss in ecosystem goods and services, costing an estimated US$6.3 trillion a year (WRI 2017), and is increasingly gaining attention in the development agenda. Similar analyses have been carried out for coastal ecosystems (Pendleton et al. 2012; Nichols et al. 2019). Approaches to addressing land and coastal degradation include land-degradation neutrality, forest landscape restoration, and ecosystem restoration as championed under the UNCCD, UNFCCC, and the Convention on Biological Diversity (Achi target 15). These approaches are also embedded in the UN sustainable development goals (SDG), particularly under SDG 13, 14, and 15. Additionally, reversing land degradation and restoring ecosystems are seen as attractive nature-based solutions to climate change adaptation and mitigation. A recent study identifies and quantifies 20 conservation, restoration, and improved land management actions that increase carbon storage and/or avoid greenhouse gas emissions across global forests, wetlands, grasslands, and agricultural lands. They estimate that these 20 “natural climate solutions” (NCS) can provide 37% of cost-effective CO2 mitigation needed through 2030 for a >66% chance of holding warming to below 2 °C. They suggest their analysis provides a robust basis for immediate global action to improve ecosystem stewardship as a major solution to climate change (N.B. the authors define a <2 °C “cost-effective” level of mitigation as a marginal abatement cost not greater than ∼100 USD MgCO2−1 as of 2030) (Griscom et al. 2017).

This study is underscored by the recent IPCC report on land and climate change (IPCC 2019, 1543 pp.), which sets out in considerable depth of the linkages between people, land, and climate. It identifies the adaptation and mitigation response options, how these can be enabled and the required near-term actions. Specifically, it identifies that many land-related responses that contribute to climate change adaptation and mitigation can also combat land degradation and enhance food security. One of the key actions is sustainable land management which by reducing and reversing land degradation, at scales from individual farms to entire watersheds, can provide cost effective, immediate, and long-term benefits to communities with co-benefits for adaptation and mitigation. Enabling response options included in the report include; “The appropriate design of policies, institutions and governance systems at all scales. These can be enabled by improving access to markets, securing land tenure, factoring environmental costs into food, making payments for ecosystem services, and enhancing local and community collective action. The effectiveness of decision-making and governance is enhanced by the involvement of vulnerable local stakeholders…. Near term actions are to build individual and institutional capacity, accelerate knowledge transfer, enhance technology transfer and deployment, enable financial mechanisms, implement early warning systems, undertake risk management and address gaps in implementation and upscaling” (extracted from IPCC 2019 our emphasis). According to the report these near-term actions can also bring social, ecological, economic, and development co-benefits that can contribute to poverty eradication and more resilient livelihoods for those who are vulnerable (IPCC 2019). The community eco-credit approach described here is designed to address many of these issues at the local level with a high level of community self-determination and engagement. Better ecosystem stewardship, which essentially (but not exclusively) means governance (including tenure and rights), will also support community stewards to adapt to climate change, through building resilience within interlinked social-ecological and socio-economic institutions at the community level. Resilience here means conserved and where necessary restored, well managed, and productive ecosystems, strong, fairly governed institutions, and integrated robust financial systems.

Increasing Availability of the Financial Resources for Ecosystem Restoration and Management

In addition to this, the financial resources to achieve ecosystem and land conservation and restoration at scale are now becoming available. Since 2006, when land degradation became a focal area, the Global Environment Facility has invested more than US$1 billion in sustainable land management practices (GEF 2019). Newer mechanisms such as the US$300 million Impact Investment Fund for Land Degradation Neutrality (UNCCD 2019) and the Green Climate Fund, which has received US$7.2 billion and which includes ecosystem restoration in its portfolio (World Bank 2019), are also supporting these efforts. However, efficiency, effectiveness, and very importantly equity remain critical questions, which must be addressed if public support is to be retained for this type of expenditure of public funds.

Urgency to Engage the Unbanked Rural Majority in Face of the Climate Emergency

Climate change is happening more rapidly than predicted (IPCC 2019), with deeper and more serious climate-related disasters of increasing frequency and severity. This engenders a greater sense of urgency with the need to help communities and broader society to adapt to climate change and restore the capacity of ecosystems to absorb carbon. While restoring land sounds an appealing solution, the reality is that many communities remain locked into a resource-poor existence unable to make the necessary investments in labor, time, and land to restore their ecosystems upon which they depend. It is also important to remember that vulnerability to climate impacts disproportionally affect marginalized members of many communities including women, youth, and elderly who are exposed to greater risks (Deering 2019).

The Need for Green Inclusive Finance to Incentivize Adaptation Actions of Rural Producers

In this chapter, we refer broadly to small-scale rural producers meaning female and male farmers (including pastoralists), fishers, and foresters that manage customarily or privately owned as well as the common pool land and sea resources. We prefer this term over smallholders or small-scale farmers as these terms imply livelihood options and tenure assumptions that may not hold true. In the literature, however, these latter terms are frequently used (e.g., Dalberg 2012, 2016; Verdone 2018) and are therefore are used here somewhat interchangeably.

Dalberg (2012), in their analysis of the financial needs of unbanked small-scale farmers, recognized that “These smallholders also represent stewards of natural resources that are in need of sustainable management to prevent deforestation and degradation of ecosystems” and further noted that “Smallholder farming methods often turn to survival tactics that degrade the ecosystems farmers depend on. Constrained by low productivity and an inability to invest in their property, smallholders sometimes resort to shorter-term measures such as illegal logging, slash-and-burn agriculture, and intensive monoculture that impairs the viability of the ecosystems they depend on.” Dalberg (2016) identifies this group to be 450–500 households million representing 2 billion people. Similarly, Verdone (2018) focusing on forest resources estimates that worldwide 1.5 billion smallholders depend on forest landscapes to produce food, meet their subsistence needs, and generate income. If small-scale fishers are added, this number is likely to increase. Dalberg 2016, considers that 80% are unbanked as they present too high credit risk for private sector investment (through credit or value chains). This represents a significant and largely unrecognized barrier to apply natural solutions to climate change especially via private sector investment (including impact funds). It is further noted that access to credit has been recognized, along with extension and information, to be the main drivers behind adaptation to climate change at the farm household level (Di Falco et al. 2011).

Given, therefore, that rural communities are severely cash constrained and that conservation often imposes opportunity costs, finding appropriate inclusive financial incentive mechanisms, including credit, for climate change adaptation and mitigation is critical. Approaches developed thus far include payments for ecosystem services (PES) and reducing emissions through deforestation and forest degradation (REDD). While huge investments have been made especially in REDD (and REDD+), progress has been slow (Clements 2010; Brockhaus et al. 2015; Börner et al. 2017; Ferraro 2017; Milbank et al. 2018; Andrews et al. 2020). An approach that has not been well explored is using inclusive finance and community savings and loan models to incentivize ecosystem management or restoration activities. We suggest this approach needs great attention and could also support the scale-up of both PES and REDD+.

Defining Inclusive Eco-credit

This chapter now sets out to define eco-credit and outlines an idealized theory of change which it incentivizes (Table 1). Eco-credit is here defined as “credit that is conditional on ecological actions undertaken by the borrower as required under loan terms.” The term was coined by the start-up company F3Life (https://f3-life.com), the winner of the UN prize for climate change finance innovation in 2014 (UNDP 2014). Inclusive eco-credit can be further divided into two types – community and commercial and defined here. “Community eco-credit,” which is the subject of this chapter, is defined as “credit, managed at the community level, conditional on ecological actions undertaken by the community member borrower required under the loan terms.” “Commercial eco-credit” is defined as “credit issued by a commercial lender, conditional on ecological actions undertaken by the borrower required under loan terms.” Eco-credit can be considered nested within Inclusive Green Finance (IGF) defined by Schuite and Forcella (2015) as a financial sector that aims to support sustainable solutions, green products, and services to poor households and Micro, Small, and Medium-Sized Enterprises (MSMEs). IGF is an area that is receiving increasing policy attention, although mainstream financial institutions are only now beginning to take up the responsibility of climate change action (Alliance for Financial Inclusion 2019), and countries at the early stages of developing appropriate policy tools (Krogstrup and Oman 2019).

Community eco-credit and the Sustainable Development Goals generating a virtuous climate resilient village economy. Development funding supports community eco-credit which supports improved ecosystem management leading to sustainable production and consumption which supports economic development, poverty reduction, and community-level investments in health and education

In considering the definitions of eco-credit, several points should be noted. Firstly, the contractual actions in the community model are collectively self-determined by the community as part of their ecosystem restoration and management plan and not imposed from outside. The plan is usually facilitated by an NGO (or an agricultural commodity company working with outgrowers (e.g., tea, coffee, and cocoa), and ideally follows best practice and is located within a framework of applicable law. With regard to this framework, it should be noted that the applicable law is not always appropriate and/or consistent and that, for many ecosystems, best practice has not been elaborated, and if elaborated may not be available at the community level. Thus, much additional work is needed in this area of practice. Secondly, credit programs can include both Islamic and interest-based financial models, and so have wide applicability. Thirdly, contractual actions that are undertaken do not have to be limited to ecosystem management or restoration, but can include other environmentally positive actions (e.g., adopting an energy saving stove), or indeed the same principle could be applied to other programs such as health and education (but without an environmental dimension would not be “eco”). Fourthly, this approach can work alongside social safety net financing (e.g., cash transfers) for the poorest community members and can potentially provide a route out of reliance on government assistance programs. Finally, the eco-credit approach could also be applied to mainstream finance provided through the banking sector, as identified by the International Monetary Fund (Krogstrup and Oman 2019) and applied by banks such as Barclays (undated) that offer credit discounts to home-owners adopting climate-beneficial technologies.

The underlying idealized theory of change (Table 1) is where access to credit at the community level helps to incentivizes behavioral responses to ecosystems management from unsustainable use to long-term stewardship and sustainable use patterns. These changes help develop virtuous cycles of increased ecosystem productivity and community development supporting most of the sustainable development goals (Fig. 1). It will also be important to understand how community credit can act as a behavioral driver that motivates individual and community courses of action. Behavioral determinants can be deeply ingrained and based upon factors like culture, habit, degree of ease, perceived barriers, social norms, or identity, and it will be also ideal to understand what elements of eco-credit might prevent or encourage the adoption of the ecosystem-positive behaviors.

Community Environment Conservation Fund

Background to the Model

The CECF, a focus of this chapter, is an example of eco-credit and was initiated in 2012 in the Upper Aswa sub-catchment in the Northern Ugandan Districts of Lira, Alebtong, and Otuke. It was part of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) project Building Drought Resilience through Land and Water Management (BDR). The project was implemented in the basins of the lower Tana River in Kenya and Upper Aswa River in Uganda. The project used IUCN’s Resilience Framework – RESFRAM (Smith 2011) and was funded by the Austrian Development Cooperation. It aimed to improve the resilience of dry-land communities to the impacts of severe and frequent drought.

Settlers in the project area were formerly from agro-pastoralist communities, who had settled after over 20 years of disturbance from civil war. Baseline data collected in April 2012 indicated that the newly settled communities were over-exploiting their natural resources to meet immediate survival needs given the limited livelihood options available to them. At that time, the communities’ reliance on natural resources was not, however, guided by any significant rules or set practices. Traditional management systems had been eroded during the war and new, statutory ones were only weakly enforced, if at all. As such, the unregulated exploitation of natural resources was leading to their significant degradation, and this degradation was in turn exposing those dependent on this livelihood approach to threats, such as climate change and disease. Wetlands and streams were being farmed right up to, and sometimes even into, the actual channel, and trees were being cut for charcoal, especially, the shea tree (Vitellaria paradoxa) which traditionally was protected due to its oil and other benefits. Such actions were increasing the potential for floods and the susceptibility to drought as a result of the reduced quality and quantity of water. Communities were caught up in a vicious cycle where they were both reliant upon, while also degrading, their natural resource base.

Implementing the IUCN Resilience Framework – RESFRAM

The IUCN RESFRAM approach promotes consideration of the following four components.

-

1.

Diversity of the economy, livelihoods, and nature. Diverse markets or farming systems give women and men the alternatives they need to be adaptive. Enhancing and protecting biodiversity by maintaining, or recreating, natural diversity also ensures the availability of the ecosystem services needed to buffer climate impacts, such as storage of water in vegetated riverine habitats, and sustains life and productivity.

-

2.

Sustainable infrastructure and technology – landscape management that recognizes, encourages, and combines the presence, development, and maintenance of both engineered and “natural infrastructure,” as well as adaptable, equitable, and sustainable technologies for their management, to reduce vulnerabilities. Infrastructure includes not only engineered responses, such as the sinking of boreholes, but also “natural infrastructure,” such as healthy and functioning wetlands and floodplains that store water, lower flood peaks, or buffer surrounding lands from flooding.

-

3.

Self-organization – a critical characteristic of resilient, highly adaptive communities is participatory governance, and self-empowerment.

-

4.

Learning – ensuring that individuals (women and men) and institutions are availed, and can make use, of new skills and technologies as they become available helping them to make more effective use of information, and thus to develop effective adaptation strategies.

The IUCN team in Uganda examined different options to implement the resilience framework. One approach considered was to support what is often called alternative livelihood activities. In IUCN Uganda’s experience, such alternatives have often been determined by external actors, been very unrealistic and, frequently, not in line with the differentiated livelihood priorities and aspirations of the women and men to whom they are promoted. Another approach considered, common in social safety net programs, was to directly pay people to carry out activities such as tree nurseries and soil conservation practices. This approach meant that extensive project delivery infrastructure would have been needed to deliver and monitor the work, which would not have been efficient nor sustainable. In addition, it would not have strengthened governance at the community level, a key feature of IUCN’s work.

IUCN Uganda consequently developed its own approach that it called the CECF) (IUCN 2013). The CECF funding works by providing a grant for the establishment and capitalization of a community revolving credit fund to communities who have collectively agreed to develop and implement an environmental management plan. This means that environmental management work is promoted, undertaken, and monitored by whole communities, including different household compositions, to ensure receipt of the credit facility, but that the money itself can be borrowed and used for any purpose, for example, from paying school fees and hospital and doctors’ bills to investments and other activities. In this way, the provision of the fund delivers improved environmental management because it enables improvements in livelihoods by removing barriers to accessing credit and not by prescribing specific actions. This is more effective than “traditional” conservation funds for alternative livelihoods because livelihood priorities are very dynamic and dependent on the status of a household at any point in time.

CECF Principles

The CECF was based on the Village Savings and Loans Association (VSLA) model (IUCN 2013), developed by CARE International and widely used in northern Uganda as an economic empowering mechanism for communities, and especially women, to access credit and build a resource base to tackle poverty (CARE 2017, 2019). Although derived from VSLA, the CECF model incorporated variations geared toward enhancing sustainable natural resources management (IUCN 2013). These have made it a unique tool to support climate change adaptation and to catalyze community-level implementation of the resilience framework. The CECF is based on seven key principles:

-

1.

The Community Environment Conservation Fund should enhance natural resources management and governance within the area under consideration.

-

2.

It should promote and be clear on individual and collective incentives and actions.

-

3.

It should enhance self-determination. Conditions for using the fund should not be prescribed but should be acceptable enough to meet general conditions.

-

4.

It should be an all-inclusive system that all categories of society (e.g., including women, younger, and elderly people, women-headed households, Indigenous Peoples) have an opportunity to participate in and make decisions on (conditions should be attainable by all members of society).

-

5.

It should be transparent and highly accountable with both effective rewards and sanctions.

-

6.

It should be linked to local governance systems; local government should provide legitimacy to the system by providing oversight.

-

7.

It should be a revolving fund, sustainable over the long-term, and should be considered as a village social fund, and a permanent community-level asset, designed to attract and catalyze more support.

Self-determination is essential as this stimulates community collective action and ownership, therefore, community land-use plans are not determined by outsiders (Ostrom 1990). In this regard, the approach follows the first principle of the ecosystem approach that the ecosystem is a result of societal choices (Shepherd 2004; CBD 2019). The plans, however, needed to be compliant with local laws and wherever possible be supported by best practice. The project and government facilitators engaged with that process played the role of advising compliance with the legal framework and adopting best practice. It should be noted that the legal framework itself is often outdated, can be contradictory and does not always follow best practice. In the realm of managing complex ecosystems, best practice is itself evolving and sometimes contested.

CECF Results

In the intervening years from 2012 to the present (2020), the CECF has been implemented in three locations in Uganda, the Upper Aswa, the Rwizi River basin in the south-west and Mount Elgon, as well as at individual pilot sites in Malawi, Kenya, and Tanzania. The methodology has generated considerable interest as a scalable, replicable, adaptable, and cost-effective tool with the potential to build the financial, environmental, and social capital of participating communities who are (i) dependent on natural resources for their livelihoods, and (ii) vulnerable to the impacts of climate change.

As mentioned, the approach has been subject to a number of reviews including Kakuru and Masiga (2016) (for Upper Asswa); Ellis-Jones et al. (2018) for Uganda and Kenya; a World Bank review (2017), and Mott MacDonald Reports (Mott MacDonald 2018a, b) for the Shire basin in Malawi; and Roberts (2017) and Wild (2019) for Pemba Island, Zanzibar, Tanzania.

In Malawi, the Ministry of Agriculture, Irrigation, and Water Development with World Bank support and technical assistance from Mott-Macdonald Ltd. have been using CECF to support watershed catchment management in the Shire River basin (Mott Macdonald 2018a, b). This component of the program was operational from 2016 to 2018 and supported the formation of 185 CECF funds. Early indications were positive and the CECF was instrumental in stimulating communities to take up actions in their village land-use plans. The project, however, has subsequently closed and the technical support is no longer in place – a follow-up is therefore recommended to assess how these are progressing and if they have survived the post-project cessation of technical support. In Pemba Island, the system has been tried for the first time with marine communities. Here GreenFi System Ltd. is supporting a Tanzanian NGO Mwambao Coastal Community Network to apply a modified approach with the members operating in groups of 30, with more specific environmental commitments, and using mobile phone technology for tracking. In this case, the background situation was examined in detail (Roberts 2017). A recent review indicated that the groups in the pilot community are progressing and the approach is appreciated at the community level (Wild 2019).

Of these reviews, the most exhaustive was Ellis-Jones et al. (2018) for Uganda (Lira, Mt. Elgon, Rwizi) and Kenya (Garissa and Tana River), and has been drawn upon to provide more detail. The overall purpose of that report was to assess the verifiable impact of the CECF approach to (i) inform design and implementation of systems which strengthen the CECF methodology in order to create a robust platform and credible basis for scale-up, and (ii) help build a richer story for IUCN to communicate the success and potential of the CECF methodology to potential funders.

The importance of a scalable methodology and credible financial, environmental, and social impact reporting is to (i) demonstrate return on investment for investors in a hybrid market-based/donor-funded model, (ii) show the cost-effectiveness of the CECF methodology in a crowded market-place for conservation concepts, and (iii) maybe most importantly, give IUCN management enhanced control over CECF implementation and performance such that the scaling is efficient and effective – and the methodology continues to be effective at scale. The review was constrained in terms of reporting impact by the lack of an impact monitoring protocol in the CECF Guidelines, particularly for assessing verified environmental and social impact. Financial data were available at project sites, however, but again there was no uniform methodology for loan tracking in the CECF Guidelines.

External Funding for CECF Groups

In terms of the review result, and most importantly, there appears to be a compelling case that community credit groups can be seeded with outside funds and, with the correct external mentoring, successfully manage this fund injection as a revolving credit facility. This is an important finding because the more established Village Savings and Loan Association (VSLA) methodology does not encourage group seeding with capital that has not been provided by the group members themselves, which has been a threat to the assumptions which underpin the CECF model. In discussing this with CARE, this contributes to the risk that group formation is principally for the purpose of receiving funds, a problem that is frequently encountered (Pennoti, pers. comm.).

However, it is important that external support and mentoring is maintained for groups in the initial phases and until such times that groups can be graduated. In Mt. Elgon, apparently most groups are inactive, and this appears to be because CECF was used as an exit strategy from a project site. This demonstrates that the CECF methodology requires patience in nurturing and developing groups to a point where they are self-sufficient in managing themselves. Further experiments are needed to uncover how much supervision and for how long groups need this support in order to stabilize, and at what time they can be graduated and where both loan cycles and improved ecosystem governance can continue independently and with low or no external support.

Verifiable Financial, Environmental, and Social Performance

In the Ugandan project, (i) groups were relatively large (with approximately 200 borrowers per group, although not all group members used their borrowing rights), and (ii) loan size were relatively small (average size US$15 to 16.50). Loan size was likely a function of group size and fund caps, whereas loan size should ideally be informed by a credit needs analysis during project design, which in turn informs the fund cap. In Garissa, Kenya, average loan sizes were close to what would be expected for unbanked individuals (US$113 for individual loans), however the Garissa project was still at an experimental stage having recently transitioned from individual loans to “group loans,” a move that itself needs further analysis.

Across key sites (Lira and Garissa), late repayments were relatively low (92% of loans repaid within 5 days of the due date). However, defaults were not tracked. This was partly because group enforcement was good, and loans were marked as repaid, even though they were repaid through the sale of a borrower’s assets, which is technically a default.

It was found that groups are willing to accept environmental conditionality as a term for loan access, but it was unclear the extent to which they complied with these terms later. Nonverifiable forms of evidence suggest that compliance is good, with reports of riverbank and stream protection, tree protection and planting, and numerous ecosystem governance institutions forming, but a robust environmental monitoring methodology is needed to verify these perceptions. CECF environmental obligations are quite complex, and likely impose both a financial and cognitive burden on members, which may act differently across age and gender groups. It is unclear what impact simplification of CECF-access terms may have in terms of boosting compliance, but once robust monitoring mechanisms are in place this can be tested.

The VSLA methodology, upon which CECF draws, was established to create positive social impact. And over decades, the approach has proven its value. The CECF methodology is new by comparison to VSLA – and offers a different value proposition in terms of social impact: improved welfare through improved natural resource management (as well as access to credit). This makes demonstration of the CECF impact very important, and the review recommended that the CECF Guidelines should include a robust social impact monitoring methodology to demonstrate its proposition.

Gender equity was largely achieved in CECF as inferred from the financial data. This was a good achievement given that there is no clear protocol to achieve this in the CECF Guidelines. Best practices need to be codified to ensure they are replicated in scale-up. Anecdotal reports which are quite widespread that CECF helped reduce the domestic violence by allowing women to have an independent source of income needs further research and analysis.

CECF Conclusions

Overall, the CECF was seen to be successful and hold significant promise but requires higher early years’ investments to achieve stability before groups are graduated. Ongoing support is likely to be necessary for groups to sustain action. As yet, how this is provided is not clear. Overall the CECF was seen in the review to be:

-

Generally successful and popular with communities. There has, however, been one failure where the scheme was used as an exit strategy at Mount Elgon. With no follow-up support, it did not become rooted and the vast majority of groups did not survive long.

-

Environmental monitoring, however, has not been strong, with general anecdotal reporting of environmental gains and no systematic collection of environmental data.

-

The model has evolved in different ways in different locations (Rwizi and Garissa).

It has now been tested with agro-pastoralists, pastoralist, smallholder farmers, and coastal fishers, as well as part of catchment management, and using both interest-based and Islamic finance models in three sub-Saharan African countries and with some additional key elements is ready for scale-up.

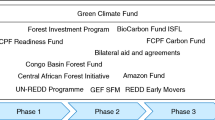

Other Community-Level Financial Infrastructure for Climate Change Adaptation

In this chapter, we have identified how this work can be located within a comprehensive financial infrastructure of complementary approaches for ecosystem governance at the community level. These existing complementary approaches that could work very effectively together are set out below and illustrated in Fig. 2. The key components of the model financial infrastructure at the community level to promote stewardship are:

-

Community eco-credit (e.g., Community Environment Conservation Fund, the focus of this chapter)

-

Commercial eco-credit (e.g., Climate Smart Lending Platform)

-

Savings groups (e.g., Village Savings and Loans Associations)

-

Value chains that support ecosystems (e.g., sustainable agriculture, forestry, fisheries, and tourism)

-

Government social safety nets (e.g., work programs or cash transfers) and internal community labor

The Climate Smart Lending Platform

The Climate Smart Lending Platform builds eco-credit into the loan terms of commercial microfinance lenders that typically address the credit needs of the better off 10–20% of community members within a specific community. (This rule of thumb depends on the extent to which households are embedded in paper-trailed supply chains. For example, a pastoralist might be richer than a small farmer on half an acre. But because the farmer is selling into a paper-trailed supply chain, she will be able to attract credit and the pastoralist may not.) The Climate Smart Lending Platform is, therefore, commercial eco-credit, and works with microfinance banks to incorporate climate-smart agricultural and land-management practices into loan terms. When a client signs a loan agreement, they also sign a land management agreement which requires the client to manage their land in a way which is designed to protect them and their farm from climate change-related events. This approach is designed to enhance credit-provider profitability by reducing credit default risk and increasing the client debt service coverage ratio. Additionally, it ensures farmers are building resilience to weather events associated with climate change (Climate Policy Initiative 2015; Partnership for Forests 2018). A successful proof of concept trial with 75 farmers was carried out in the Nyandarua county of Kenya, in 2015. It complements community eco-credit (e.g., the CECF) as it works with the better off members of the community. The two approaches have yet to be tested in the same location.

Village Savings and Loans Associations

CARE International, the leading proponent of savings-based social lending, created the Village Savings and Loans Associations (VSLA) model in Niger in 1991, and has since brought VSLA programming to many different regions and continents, adapting it to different contexts as its reach expands (CARE 2017). Thus, this is a tried, tested, and now massively scaled savings-led, community-based financial solution. CARE deliberately set out to scale it up in 2009, and has since expanded access to from an initial 1 million members in 2008 to 7.6 million across 51 countries today. These members represent 357,000 groups of predominantly rural, poor women collectively saving and investing over US$500 million per year (CARE 2019). CARE’s investment in growing VSLAs and its broad-based industry engagement has allowed it to significantly multiply its impact; more than 26 other NGOs and several governments are implementing savings group programming at scale modeled on VSLA. This work has resulted in over 15.2 million VSLA members world-wide who are saving and investing in their respective communities (CARE 2017). 59% of CARE-trained VSLA members are in East Africa, 17% in West Africa, 13% in Southern Africa, 10% in Asia, and 1% in Latin America. There have been many studies on the impact of VSLA including randomized trials (e.g., Ksoll et al. 2016). These studies of VSLAs have found evidence of significant positive outcomes, including the number of meals consumed per day, household expenditure, and the number of rooms per dwelling. This effect is linked to an increase in savings and credit obtained through the VSLAs, which has increased agricultural investments and income from small businesses (Ksoll et al. 2016). While some attempts at greening VSLA have been made (Wild et al. 2008), the model has primarily focused on the social and financial double bottom line (Pennotti, pers. comm.). The VSLA financial infrastructure is now widespread and deeply embedded at community level and presents a huge foundation for scaling eco-credit if environmental actions can be integrated into group actions. To take one example, the northern Zanzibar Island of Pemba has over 90 VSLA trainers organized through a formerly CARE supported local NGO Pemba Savings and Credit Association (PESACA) (Wild 2019) could support the evolution of eco-credit. The VSLA model was the basis for the CECF innovation.

Sustainable Value Chains

The restoration and better management of ecosystems and the increased ecosystem productivity it brings will of itself enhance community livelihoods. However, the more that these are linked in with value chains that support and do not undermine these ecosystems from which they derive products, the greater the livelihood and income generation benefits will be generated. Further, the increase in community incomes is likely to increase the pace of scale-up and improve the chance of engaging the private sector in climate change adaptation. Many agricultural, forestry, fisheries and tourism-based value chains could fit into this category. The advantage of the eco-credit approach is that it is very scalable, overcoming the geographical scale limit of individual value chains. If tea, coffee, shea nut, sustainable forestry and agriculture companies all took a community eco-credit approach, they would not only green their value chains, but collectively would have significant climate change adaptation impact over wide areas. The recommendation is, therefore, that these commodity companies adopt a community eco-credit approach to support their communities of outgrowers with setting up and capitalizing community eco-credit funds. In addition to securing their produce value chains through sustainable land management, the commodity companies would enhance their social license to operate. Following the lead of the major land-based commodities, this could be replicated among the less organized agriculture, forestry and fisheries-based value chains.

Social Safety Net Funding and Internal Employment

A common feature in many societies are payments to vulnerable households via government social safety net systems. This is a broad topic and the purpose of highlighting it here is that (a) if these safety nets were aligned with ecosystem management and restoration and (b) if VSLA and CECF are recognized as potential routes out from the need of social safety nets, then funding would align for greater impact. The internal use of employment and piece work within communities is also common, where better off community members employ less well-off community members in activities such as digging land, collecting water, and firewood (Whiteside 2000). We expect internal employment to be an integral feature of community financial infrastructure that we outline supporting profitable climate adaptation activities, however, this requires further research.

Scaling Up Community Eco-credit

As eco-credit is relevant to most rural communities in the global south, and it has a very significant scale potential to assist communities to adapt to and mitigate climate change. We briefly outline here two elements that will be important for scale-up: (a) technology platforms and (b) large-scale funding, for example, a blended finance fund.

Technology: Mobile Phone and Web-Based Applications

For community eco-credit systems to scale-up effectively, technological solutions will be required. Indeed the 20,000 member strong CECF in Northern Uganda has probably reached the maximum scale possible on an analog system alone. Technology allows scale-up as it reduces the costs of the credit transactions, allows detailed monitoring of both financial and environmental performance, and allows organizations both using and providing grant finance to have real-time reporting on the use and impacts of their funding. These technology systems should include the following key elements:

-

Core banking systems

-

Environmental monitoring and verification

-

Additional elements that will be developed in time

-

Upload community land-use and action plans

-

Boundary and way marking

-

Baseline ecological conditions

-

Baseline social conditions

-

Loan use and effectiveness – enterprise tracking

-

Extension and information via training modules and push SMS

-

Impact at social level – attribution to education and health outcomes

-

Establishing Large-Scale Funding

A barrier to the significant scale-up of community eco-credit is the capitalization of community eco-credit funds (e.g., CECF and similar). It is estimated that the resources required for each independent community-level eco-fund is in the range of US$1,500 to US$10,000 depending on the socio-economic baseline. There are good reasons to develop dedicated funding mechanisms to capitalize the community-level eco-funds.

IUCN, CARE International, and GreenFi Systems Ltd. developed a concept for a US$1-2 billion fund which was submitted to the 2019 and 2020 calls for the Global Innovation Lab for Climate Finance. The concept, called MaliVerde MaliBulu – meaning green wealth/blue wealth, was among the finalists, indicating that the creation of a specific fund vehicle could potentially gain traction (IUCN 2019).

The goal of the fund was to establish a US$2 billion, 10-year fund to capitalize community eco-credit groups, with the aim of restoring the ecological function and carbon sequestration over large areas of land and seascape. If such a fund was successfully established, then community-level; eco-funds could be replicated in different geographies and targeting specific resources and livelihoods (pastoralism, agriculture, fishing, etc.). If US$2 billion, for example, were deployed into a fund or funds, it was considered that this would scale by 300% in 10 years, and 6,000% in 30 years, meaning 150 million small-scale producers in a decade, and (feasibly) a large proportion of unbankable small-scale producers globally would have access to capital and be contributing to nationally determined contributions (NDCs) to the climate emergency. As it is primarily focused on unbankable community members, the fund would need to adopt a blended finance mechanism, with development partners and aid agencies and large-scale climate financing providing a substantial grant element. The private sector would come in progressively as the groups became either part of an existing value chain (tea and other commodities), or established by a project finance model where the development finance absorbed the risk but the established funds being paid for by the private sector entity. The potential sources of resources and co-resources to establish the community eco-funds can be seen in Fig. 3.

Discussion

Scale Relevance of Community Eco-credit

Dalberg (2012, 2016) identifies that only 10–20% of the 450 million smallholder farm households (representing 2 billion people) receive commercial loans mostly through short-term trade finance, through export-based commodity value chain actors (e.g., tea, coffee, etc.). The authors outline the importance of this group not only to delivering food security (SDG 2) but also as ecosystem stewards (SDG 14 and 15).

Donors consider the world’s 450 million smallholders a linchpin in poverty-reduction strategies because more than two billion of the world’s poorest live in households that depend on agriculture for their livelihood. These smallholders also represent stewards of natural resources that are in need of sustainable management to prevent deforestation and degradation of ecosystems (our emphasis). (Dalberg 2012)

The authors identify the opportunities of working with this group but point to a further set of challenges:

-

Smallholder production (<2 ha) is low quality with poor market linkages and little finance. Unmet global smallholder finance is estimated at US$450 billion.

-

Agricultural “social lenders” satisfy less than 2% of the demand.

-

The vast majority of smallholders are nonaggregated only about 10% of smallholders currently belong to producer organizations.

The authors also note the contribution of VSLA as to informal finance (Dalberg 2016).

In a similar analysis, Verdone (2018), focusing on forest resources, also identified the often-overlooked economic potential of what is possibly the world’s largest private sector. He reported estimates that “more than 1.5 billion smallholders throughout the world depend on forest landscapes to produce food, fuel, timber and non-wood forest products to meet their subsistence needs and generate cash income. Despite the large number of smallholders and the large collective scale of their production, policy makers have overlooked smallholders’ role as a powerful economic engine” (Verdone 2018). If small-scale fishers are added, this number is likely to increase. This group constitutes the largest private sector although they are typically not considered so within the government policy of a number of countries. The Dalberg (2012) report identifies five primary growth pathways for deploying investment to address the current vacuum in smallholder finance:

-

(i)

Replicate and scale existing financing models, such as the model proven by social lenders

-

(ii)

Innovate new financial products beyond short-term export trade finance

-

(iii)

Finance out-grower schemes of multinational buyers in captive value chains

-

(iv)

Finance through alternate points of aggregation in the value chain

-

(v)

Finance directly to farmers

Advantage of Community Eco-credit

We consider that the community eco-credit model could become a widespread additional tool in the financial toolbox that could influence several of these growth pathways because:

-

1.

It incentivizes the stewardship of ecosystems and natural resources and supports the increased productivity of and income from these ecosystems and natural resources. This structure support changes in behavior leading to better ecosystem and livelihood outcomes for communities.

-

2.

It aggregates farmers based on ecosystem/natural resources type and not primarily on value chains (although value chains do flow out of this ecosystem-first approach).

-

3.

It is based on rights holders looking for partners – not capital looking for resources and labor (see below).

-

4.

It provides, through grants to communities, the ability for smallholders to take loans and build up credit history.

-

5.

By linking eco-credit group capitalization, it would also incentivize the greening of local business development.

Community eco-credit therefore provides one route for unbankable community members to develop a credit score, such that eventually, and with appropriate duty of care, they can bear a commercial loan, necessary to finance, for example, more expensive climate mitigation or adaptation technologies.

Aggregation for Ecosystem Management

In the eco-credit model, aggregation is via community institutions, not to meet the needs of a value chain of a commercial entity, but to better organize effective ecosystem restoration and management, and enhance ecosystem productivity. It comes from a different basis identified as “investing in locally controlled ecosystems (e.g., forestry)” (Elson 2012), representing a paradigm shift – away from capital seeking ecosystems and needing labor – toward local rights-holders managing ecosystems and seeking capital. It recognizes the need to distinguish and blend two types of investment:

-

Asset investment (conventional investment in which the nominal value of underlying capital is expected to increase or at least not fall)

-

Enabling investment (in which capital is foregone to build the self-sufficiency and attractiveness of the business in question)

Conclusion and Recommendations

The increasing recognition of the unfolding climate emergency has increased the urgency for public and private investment in ecosystem management and restoration as a key adaption and mitigation mechanism. Globally small-scale producers; fishers, foresters and farmers/pastoralists are the largest single group of stewards and primary investors in these ecosystems. Despite access to credit being a main driver behind adaptation to climate change at the farm household level (Di Falco et al. 2011), these groups are hardly served, and in fact are considered largely unbankable by the formal banking sector.

There is a great need therefore to find ways to fill this vacuum and bring inclusive finance for climate change adaptation to these communities. The CECF case study described here, using the concept of eco-credit, builds on the existing solidarity finance mechanisms which serve this group. It builds climate adaptation and ecosystem management actions into loan terms and incentivizes gender-responsive adaptation and mitigation at the community level, as well as supporting individuals and households. The CECF model has been tested in several locations in East and Southern Africa over 8 years and is ready for significant scale-up. Scale-up will be supported by the development of appropriate technology platforms and the development of a blended finance vehicle to capitalize and provide technical assistance to the eco-credit groups.

Other complementary mechanisms if used in the same location will significantly strengthen the CECF model. These complementary mechanisms include the commercial eco-credit of the Climate Smart Lending Platform, aligned VSLA groups, value-chains that do not undermine ecosystem, and where needed and aligned, social safety net funding. To fully take advantage of this model, we make the following recommendations:

-

Scale-up and expand the operation and delivery of local autonomous community eco-credit funds.

-

Make funding available to capitalize community eco-credit funds through the creation of large-scale blended finance vehicle (>US$2 billion) capitalizing this vehicle from multilateral and bilateral programs, carbon credits, private project finance, payments for ecosystem services, and corporate social responsibility.

-

Support the development of value chains that support ecosystem restoration and sustainable-use that help communities conserve those ecosystems and support increased ecosystem productivity and poverty reduction.

-

Commodity value chain companies with outgrower schemes (e.g., tea, coffee, cocoa, and timber) introduce eco-credit to their communities to enhance sustainable land and ecosystem management.

-

Carry out further research into this model, individual, and behavioral responses and provide lessons and pathways for enhanced scale-up, including improved mechanisms for recording eco-compliance.

-

The conservation community to provide more extensive and practical guidance in equitable sustainable management and conservation of ecosystems at the community level to enhance ecosystem productivity for local wealth generation.

-

Explore the use of community eco-credit to support PES and REDD+ schemes.

References

Alliance for Financial Inclusion (2019) Inclusive green finance: a survey of the policy landscape. AFI special report. Alliance for Financial Inclusion. https://www.afi-global.org/publications/3036/Inclusive-Green-Finance-A-Survey-of-the-Policy-Landscape

Andrews J B, Caro T, Said Juma A, Collins A C, Bidawa Bakari H, Hassan Sellieman K, Abdi M, Assaa Sharif N, Borgerhoff Mulder M (2020) Does REDD+ have a chance? Implications from Pemba Tanzania. Oryx 54(3):1–7

Barclays Bank (undated) Treasury Select Committee: inquiry into the decarbonisation of the UK economy and green finance submission by Barclays Bank. https://home.barclays/content/dam/home-barclays/documents/citizenship/our-reporting-and-policy-positions/policy-positions/Treasury-Select-Committee-Barclays-Green-Finance-Inquiry.pdf

Börner J, Baylis K, Corbera E, Ezzine-de-Blas D, Honey-Rosés J, Persson UM, Wunder S (2017) The effectiveness of payments for environmental services. World Dev 96:359–374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.03.020

Brockhaus M, Korhonen-Kurki K, Sehring J, Di Gregorio M et al (2015) Policy progress with REDD+ and the promise of performance-based payments: a qualitative comparative analysis of 13 countries. CIFOR working paper 196, Bogor Indonesia

CARE International (2017) CARE Global VSLA Reach 2017: an overview of the global reach of Care’s Village Savings and Loans Association programming. https://insights.careinternational.org.uk/media/k2/attachments/CARE-VSLA-Global-Outreach-Report-2017.pdf

CARE International (2019) Unlocking access, unleashing potential: empowering 50 million women and girls through village savings and loan associations by 2030. CARE, Altanta

Clements T (2010) Reduced expectations: the political and institutional challenges of REDD+. Oryx 44(3):309–310

Climate Policy Initiative (2015) Climate smart lending platform. https://www.climatefinancelab.org/project/climate-smart-finance-smallholders/. Last accessed 19 Sept 2019

Convention on Biological Diversity (2019) The ecosystem approach. https://www.cbd.int/ecosystem/principles.shtml. Last accessed 19 Sept 2019

Dalberg (2012) Catalyzing smallholder agricultural finance. Dalberg Global Development Advisors, New York

Dalberg (2016) Unlocking growth in the era of farmer finance. Dalberg Global Development Advisors, New York. https://mastercardfdn.org/research/inflection-point-unlocking-growth-in-the-era-of-farmer-finance/

Deering K (2019) Gender transformative adaptation from good practice to better policy. CARE International, Atlanta

Di Falco S, Veronesi M, Yesuf M (2011) Does adaptation to climate change provide food security? A micro-perspective from Ethiopia. Am J Agr Econ:1–18. https://doi.org/10.1093/AJAE/AAR006

Ellis-Jones M, d’E Roberts J , Ngigi ON (2018) A report on CECF financial performance and environmental compliance. Unpublished report for the International Union for Conservation of nature (IUCN) November 2018. GreenFi Systems Limited

Elson D (2012) Guide to investing in locally controlled forestry. Growing forest partnerships with FAO IIED IUCN the forests dialogue and the World Bank. IIED, London

FAO & Global Mechanism of the UNCCD (2015) Sustainable financing for forest and landscape restoration: opportunities, challenges and the way forward. Discussion paper. Rome. (This publication is available for download at www.global-mechanism.org/resources/gm-publications and www.fao.org/forestry/publications)

Ferraro PJ (2017) Are payments for ecosystem services benefiting the ecosystems and people? In: Kareiva P, Marvier M, Silliman B (eds) Effective conservation science: data not dogma. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, pp 159–166. https://doi.org/10.1093/o.003.0025

GEF (2019) Land degradation. https://www.thegef.org/topics/land-degradation. Last accessed 19 Sept 2019

Griscom BW, Adams J, Ellis PW, Houghton RA, Lomax G, Miteva DA, Schlesinger WH, Shoch D, Siikamäki JV, Smith P, Woodbury P, Zganjar C, Blackman A, Campari J, Conant RT, Delgado CP, Gopalakrishna ET, Hamsik MR, Herrero M, Kiesecker J, Landis E, Laestadius L, Leavitt SM, Minnemeyer S, Polasky S, Potapov P, Putz FE, Sanderman J, Silvius M, Wollenberg E, Fargione J (2017) Natural climate solutions. PNAS 144:11645–11650

IPCC (2019) IPCC special report on climate change, desertification, land degradation, sustainable land management, food security, and greenhouse gas fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems, Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change published 7 August 2019. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/srccl/

IUCN (2013) Practical guidelines for establishing a Community Environment Conservation Fund as a tool to catalyse social and ecological resilience. IUCN Uganda Country Office, Kampala, Uganda

IUCN (2019) MaliVerde/MaliBuluu fund concept gains steam. Webstory. https://www.iucn.org/news/forests/201903/maliverde-malibuluu-fund-concept-gains-steam. Last accessed 19 Sept 2019

Kakuru W, Masiga M (2016) Implementation of the Community Environment Conservation Fund (CECF) to enhance forest landscape restoration in Uganda: emerging lessons and recommendations for scaling up. Unpublished report, IUCN Uganda Country Office, Kampala, Uganda

Krogstrup S, Oman W (2019) Macroeconomic and financial policies for climate change mitigation: a review of the literature. International Monetary Fund working paper 19/185

Ksoll C, Lilleør HB, Jonas H, Lønborg JH, Rasmussen OD (2016) Impact of village savings and loan associations: evidence from a cluster randomized trial. J Dev Econ 120:70–85

Milbank C, Coomes D, Vira B (2018) Assessing the progress of REDD+ projects towards the sustainable development goals. Forests 9:589. https://doi.org/10.3390/f9100589

Mott MacDonald (2018a) Final report component B – catchment management – Lisungwi and Wamkulumadzi. SRBMP, ISP-CM, sub-components B1–B3. Final report to the Ministry of Agriculture, Irrigation & Water Development and Shire River Basin Management Program

Mott MacDonald (2018b) Final report component B – catchment management – Kapichira and Chingale, SRBMP, ISP-CM, sub-components B1–B3. Final report to the Ministry of Agriculture, Irrigation & Water Development and Shire River Basin Management Program

Nichols C, Zinnert J, Young D (2019) Degradation of coastal ecosystems: causes, impacts and mitigation efforts. In: Wright LD, Nichols CR (eds) Tomorrow’s coasts: complex and impermanent. Coastal research library 27. Springer, Switzerland. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-75453-6_8

Ostrom E (1990) Governing the commons – the evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge UK

Partnership for Forests (2018) Climate smart lending platform partnership offers technology and data driven solution for climate resilient agri-lenders and farmers in East Africa. https://partnershipsforforests.com/2018/12/12/climate-smart-lending-platform-new-partnership-offers-technology-and-data-driven-solutions-for-climate-resilient-agri-lenders-and-farmers-in-east-africa/. Last accessed 19 Sept 2019

Pendleton L, Donato DC, Murray BC, Crooks S, Jenkins WA, Sifleet S et al (2012) Estimating global “blue carbon” emissions from conversion and degradation of vegetated coastal ecosystems. PLoS One 7(9):e43542. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0043542

Roberts J (2017) Silver bullet or red herring?: Are Community Environment Conservation Funds a suitable management tool for building resilience in coastal communities of developing countries? A feasibility study in Pemba, Zanzibar dissertation for the degree of MSc in Ecological Economics School of GeoSciences, Julianne d’Esterre Roberts 1675511 August 2017

Schuite GJ, Forcella D (2015) Green inclusive finance: status, trends and opportunities! NpM the platform for inclusive finance, Hivos & FMO

Shepherd G (2004) The ecosystem approach five steps to implementation. IUCN, Gland/Cambridge, UK

Smith DM (2011) Development and application of a resilience framework to climate change adaptation. Global Water Programme, IUCN, Gland

UNCCD (2019) An impact investment fund for land degradation neutrality. https://www.unccd.int/actions/impact-investment-fund-land-degradation-neutrality. Last accessed 19 Sept 2019.

UNDP (2014) UNDP, Mitsubishi UFJ and Morgan Stanley announce winner of climate change finance innovation award. Dec 9, 2014. https://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/presscenter/pressreleases/2014/12/09/undp-mitsubishi-ufj-morgan-stanley-announce-winner-of-climate-change-finance-innovation-award/. Last accessed 13 Sept 2019

Verdone M (2018) The world’s largest private sector? Recognising the cumulative economic value of small-scale forest and farm producers. IUCN, FAO, IIED and AgriCord, Gland

Whiteside M (2000) Ganyu labour in Malawi and its implications for livelihood security interventions – an analysis of recent literature and implications for poverty alleviation. ODI Agricultural Research & Extension Network, Network Research Paper 99

Wild RG (2019) A review of the MKUBA pilot in Kukuu Village, Pemba, Zanzibar. Unpublished report for Mwambao Coastal community Network and the Fauna and Flora International

Wild RG, Millinga A, Robinson JR (2008) Microfinance and environmental sustainability at selected sites in Tanzania and Kenya. Unpublished report for LTS, WWF and CARE International

World Bank (2019) Green climate fund trust fund financial report prepared by the trustee (The World Bank). As of June 30, 2019. https://fiftrustee.worldbank.org/content/dam/fif/funds/gcf/TrusteeReports/GCFTF-Financial-Report-as-of-June-30-2019.pdf. Last accessed 19 Sept 2019

World Bank Group (2017) First Phase of Shire River Basin Management Program (SRBMP) Project: implementation support mission – January 25 to February 6, 2017. Aide Memoire

WRI (2017) In: Ding H, Faruqi S, Wu A, Altamirano J-C, Ortega AA, Cristales RZ, Chazdon R, Vergara W, Verdone M (eds) Roots of prosperity: the economics and finance of restoring land. World Resources Institute, Washington, DC

Acknowledgments

Appreciation goes to the Austrian Development Cooperation for funding the Building Drought Resilience project where CECF was developed.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s)

About this entry

Cite this entry

Wild, R. et al. (2021). Using Inclusive Finance to Significantly Scale Climate Change Adaptation. In: Oguge, N., Ayal, D., Adeleke, L., da Silva, I. (eds) African Handbook of Climate Change Adaptation. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-45106-6_127

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-45106-6_127

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-45105-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-45106-6

eBook Packages: Earth and Environmental ScienceReference Module Physical and Materials ScienceReference Module Earth and Environmental Sciences