Abstract

Positive individual traits have been considered important by both Eastern and Western cultures. According to military academy manuals, the positive traits of individuals are significant elements for people who will hold military leadership positions. Since the dawn of the twenty-first century, positive psychology has had a positive trait classification of six virtues that include a total of 24 character strengths originating from the proposals of Peterson and Seligman. Because character strengths can be assessed using reliable and valid measurement instruments, several empirical investigations have been carried out in military populations in the American and European continents. The studies conducted on the 24 character strengths have been mostly on cadets. The results of these studies have shown that character strengths are related to the military population. Thus, the relationship between the 24 character strengths and several points of interest, such as membership in military academic institutions, cadets’ family of origin, and academic and military performance, among other findings, have been empirically studied.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download reference work entry PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

In contemporary times, encountering the terms virtue or character in academic psychological discourse may seem dissonant or exasperating (McCullough & Snyder, 2000). These terms may also evoke a Victorian or Puritanical resonance to many psychologists in the present time. However, character has been an aspect of psychology studies and proposals since the dawn of the twentieth century, although its evolution as a subject of psychology has not been linear, but intricate. In fact, character almost disappeared as a relevant topic of study in psychology. However, the study of morally valued traits has re-emerged with much strength since the beginning of the present century (McCullough & Snyder, 2000). As is almost always the case, we have not reached this situation by chance.

In the first decades of the twentieth century, before the beginning of World War II, Psychology was concerned with three important missions: to make people’s lives more satisfying and productive, to identify and develop talent, and to treat mental illnesses (Seligman, 2002).

However, in the development of psychology, there was a plain intention to exclude character-related terms from the lexicon of scientific psychology. There is a consensus among scholars that it was Gordon W. Allport who played a key role in the exclusion of character from psychology (e.g., Cawley III et al., 2000; McCullough & Snyder, 2000; Nicholson, 1998; Peterson & Seligman, 2004). Allport was a renowned personality trait theorist in the United States in the last century (Peterson & Seligman, 2004). He was among the intellectuals who stressed that the terms character and personality should be differentiated in psychology (Allport, 1921), but he went further. Allport not only negatively judged the indiscriminate use that psychologists made of character as equivalent to personality at the beginning of the last century (Barenbaum & Winter, 2008) but also strongly opposed the use of the term character in psychology (Allport & Vernon, 1930). Allport argued that character was a moral category that referred to oneself from an ethical perspective, whereas personality referred to oneself objectively (Nicholson, 1998). Therefore, he considered that the term character should be deliberately eliminated from the psychological field as a construct because it is a purely evaluative concept and that the study of character should not be included in the field of psychology. Allport’s vehement opposition to the study of character reflected, in part, the spirit of social change in the United States (Nicholson, 1998). Thus, by the 1940s, the progress of the personality framework in Psychology had become clear (Nicholson, 1998). Besides, if 1937 is considered the year of birth of personality psychology, it could also mark the beginning of the eclipse of character in psychology.

At the end of World War II, psychology became a science oriented almost solely towards the treatment of mental illnesses, and therefore, the theories, treatments, and prevention of psychological disorders marked the direction of research in the following decades (Peterson & Seligman, 2004). This approach led to essential progress in psychopathology, as evidenced by the emergence of effective treatments for more than a dozen mental disorders that had been untreatable only a few decades before. However, the other fundamental missions of psychology were almost completely neglected.

Although for decades character had not been a central theme in psychology, some psychologists within different traditions expressed themselves directly and indirectly on the positive personal characteristics or strengths of people’s character (Peterson & Seligman, 2004) as follows: Erikson proposed that positive personal characteristics resulted from the successful resolution of psychosocial stages; Maslow described positive personal characteristics as central aspects in the self-actualization of individuals; Greenberger postulated that several dimensions of the psychosocial maturity model are positive characteristics or traits; Jahoda argued that the processes producing positive mental health involve positive characteristics; Kohlberg described the stage development of moral reasoning; and Vaillant put forward the benefits of mature defense mechanisms. The works of these theorists and several others involved in their theoretical approaches to the positive personal aspects – such as Ryff, Schwartz, Cawley, Gardner, and authors of Evolutionary Psychology and Personality Psychology – as well as studies on resilience were important for the subsequent development of the study of character in positive psychology.

By the end of the twentieth century, psychology had changed its course (Linley et al., 2006). Psychologists founded positive psychology, an area within Scientific Psychology that focuses on the positive aspects of people’s lives: positive emotions, positive traits of people, and the institutions that foster the positive aspects of people. Thus, this area seeks to investigate with a scientific method the complete picture of psychological life, not only psychopathology (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000). Seligman (2002) has argued that the message of positive psychology is to return to the origins of psychology and to consider that psychology is not only the study of illness, harm, and weakness but also the study of strengths and virtues that enhance people’s quality of life.

The dawn of positive psychology is Martin E. P. Seligman’s presidential address to the American Psychological Association in 1998 (Linley et al., 2006). In that speech, Seligman, as president of this association, proposed using the quality of scientific research to reorient psychological science and practice toward the development of a new science of human strengths, in order to identify and understand the traits and foundations of psychological health, and learn how to develop positive traits in young people (American Psychological Association, 1999; Linley et al., 2006).

Positive psychology is an area of study composed of three pillars of research: the subjective, individual, and group pillars. The subjective pillar of positive psychology studies the positively valued individual subjective experiences, such as pleasure and happiness (oriented to the present), hope and optimism (oriented to the future), and well-being and satisfaction (oriented to the past). In the individual pillar, psychologists study the positive individual traits, such as the capacity to love, courage, interpersonal skills, aesthetic sensitivity, persistence, clemency, spirituality, and wisdom; in short, these are the virtues and strengths of character. Finally, in the group pillar, psychologists investigate human groups linked to the positive aspects of individuals. For example, they study institutions that encourage individuals to be better citizens (Carr, 2004; Gable & Haidt, 2005; Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000).

This chapter focuses on the pillar of positive psychology that studies character. Character is the morally valued aspects of the individual (Park & Peterson, 2009). In this sense, Park and Peterson have argued that the area that deals with the study of character is in a position of preeminence regarding the other two areas of positive psychology, the subjective and the group pillars. On the one hand, positive traits are the underpinning of positive subjective experiences, which come and go, such as positive emotions; and positive institutions, such as positive families, schools, and communities, are primarily positive because they comprise people with positive traits.

Character Strengths

Positive psychology not only recognizes morally valued traits as an important element for the characterization of good psychological functioning but also regards the study of character as a pillar or area of positive psychology (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000). The first outstanding results of the study of character in positive psychology are the works developed under the auspices of the Values in Action Institute created by the Manuel D. and Rhoda Mayerson Foundation in 2000, a non-profit organization whose objectives are the development of scientific knowledge of human strengths and the development of positive traits in youth (Peterson, 2006; Peterson & Seligman, 2004). This institution focuses its work on good character, considering the concerns of American society (Hunter, 2001). The research topics of the Values in Action institute are associated with determining what good character is and how it can be measured from the perspective of scientific psychology.

The availability at the beginning of the twenty-first century of two widely recognized and accepted classifications of mental disorders, known as the (American Psychiatric Association, 2000) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed.; DSM-IV-TR) and the (World Health Organization, 1992) Chap. 5 of the International Classification of Diseases (10th ed.; ICD-10) is part of the remarkable progress in psychopathology in the last decades. Similarly, it was important to have a classification of psychological health or human excellence of the same quality as that of the psychopathological classifications. However, at the beginning of this century, there was no broad and detailed classification of positive traits that would provide an elaborate and widely agreed-upon framework, empirically grounded and serving as the support of research, diagnosis, and interventions in positive psychology because of the scant attention that Psychology had given to the positive aspects of the lives of individuals in recent decades (Dahlsgaard et al., 2005; Peterson & Seligman, 2004). However, the work carried out under the support of the Values in Action Institute was a significant initial step towards achieving a classification with these characteristics. In the first decade of this century, a handbook was published on character virtues and strengths, the so-called Manual of the Sanities, which develops a broad and meticulous classification of positive traits (Peterson & Seligman, 2004).

The Values in Action Character Classification

The initial steps in achieving the goal of developing the Values in Action (VIA) character classification involved resolving fundamental issues about good character, such as specifications about definitions and forms of classification (Peterson, 2006). The four fundamental issues that were the subject of analysis are shown below.

-

a)

Theorists considered good character as a family of positive dispositions, such as kindness, hope, courage, and wisdom (Peterson, 2006). In addition, they decided to name the components of good character as character strengths. They assumed character strengths were, in principle, different from each other, and that people could have a high level of one character strength, while exhibiting a low or medium level of other strengths. They supposed character strengths to be a trait-like characteristic, in the sense of being individual differences with some stability and generality. However, these traits were not assumed to be fixed or grounded in immutable biogenetic characteristics. Also, to agree with a general premise of positive psychology, which stated that strengths imply more than the mere absence of distress and disorder (Seligman & Peterson, 2003), good character was assumed to be more than the negation or minimization of bad character. Finally, character strengths should be individually defined and assessed.

-

b)

They assumed that human excellence was as authentic, i.e., as “real” or as “true,” as disease (Peterson, 2006) and that character truly exists. Determining which character strengths or positive traits were culturally affected became a question to be resolved empirically. Some character strengths might only be considered in some cultures, but not in others. However, the possibility that some values and virtues are universal was also to be taken seriously. Therefore, the answers given about good living and morally good behavior in Eastern and Western religious and philosophical traditions that have had a lasting and clear impact on human civilization were examined. As a result, six virtues were explicitly or implicitly reiterated in most of these philosophical and religious traditions: courage, justice, humanity, temperance, wisdom, and transcendence. This convergence was the foundation of the VIA classification of character. In this way, the theorists expected to avoid historical or cultural bias in the classification of positive traits (Dahlsgaard et al., 2005).

-

c)

No previous psychological or philosophical theory of good character was used as an explicit framework for the classification that the researchers would develop (Peterson, 2006). Nor was any alternative theory proposed to provide the explanatory framework for the new classification. The positive trait classification does not constitute a taxonomy in the sense that no theory explains the relationships between instances of the classification (Peterson & Seligman, 2004).

-

d)

Finally, the fourth central issue to be resolved was how much detail would the classification of positive traits require (Peterson, 2006). The identification of the six core virtues suggested that one could opt for only six entries in the classification. However, the virtues appeared to be too abstract to be measured. Each of the core virtues consistently defined a related set of character strengths. For example, the virtue of humanity might include the character strengths love and kindness; despite a certain degree of conceptual overlap between them – in this case, it would be difficult to think that someone could have one and completely lack the other – the distinction was important and workable. They decided to use the strength level of classification – not the virtues – since it was assumed that the “natural concepts” used by individuals to describe good character were at the level of character strengths and not at the level of the nuclear virtues. Finally, the existence of a large variety and amount of literature dealing with character strengths could profitably be used to generate classification entries.

Characteristics of Character Strengths

After a group of scholars had taken a position on the four preliminary themes, they proposed a list of candidate character strengths for the classification, which was refined through a series of discussions (Peterson & Seligman, 2004). They also considered several sources related to good character, such as psychology courses, organizational studies, character education programs, and works in psychiatry, philosophy, and religion. Besides, they examined cultural objects, such as popular song lyrics, greeting cards, obituaries, and personal ads in newspapers, in search of character strengths; thus, the list of strengths was based on a broad exploration. They then filtered dozens of candidate strengths, combining redundancies, and 12 criteria (Peterson, 2006; Peterson & Seligman, 2004) were applied to each strength to be included in the final ranking as detailed below: being widely recognized across different cultures; contributing to fulfillment, satisfaction, and happiness; being morally valued in one’s own right and not for its tangible results; elevating others and not diminishing them, and producing admiration rather than envy or jealousy; having negative antonyms; manifesting itself in thoughts, feelings, and/or actions; and, as a trait, having some generalizability across situations and stability over time; having been successfully measured as an individual difference in previous research; not being conceptually or empirically redundant with other strengths in the classification; being widely present in some individuals, who can be consensually considered exemplary models; being precociously present in children or young people, who could be prodigies; being completely absent in certain individuals; and having institutions with associated rituals that deliberately aim to cultivate the strength and sustain its practice. After analyzing whether each proposed strength met these criteria, the VIA classification of six virtues including 24 strengths was developed (Peterson & Seligman, 2004), as described in the next section.

The VIA Classification

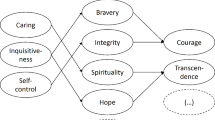

Peterson and Seligman’s (2004) VIA character classification includes the following six virtues, with the types of strengths enclosed in dashes: wisdom and knowledge – cognitive strengths that involve the acquisition and use of knowledge; courage – emotional strengths that involve exerting willpower to achieve goals in the face of external or internal opposition; humanity – interpersonal strengths that involve helping and being a friend to others; justice – civic strengths that underlie healthy community life; temperance – strengths that protect against excesses; and transcendence – strengths that forge connections to something greater than oneself, in a broad sense, and give meaning to life. It should be noted that Peterson and Seligman (2004) stated that VIA classification was tentative in nature and could be altered because of progress in the scientific study of moral excellence, so that in the future the clustering of character strengths could be revised, expanded, or contracted (Peterson, 2006). Table 1 shows the VIA classification with summary definitions for each of the character strengths.

The Structure of Character

Peterson and Seligman (2004) explained that the approach they used for the study of character was inspired by personality psychology, which recognizes individual differences that are stable and general, but also shaped by the individual’s contexts and susceptible to change. They proposed that character traits, by definition, are stable but malleable and that contextual and situational conditions, both physical and social environments, could facilitate or impair the onset or development of character strengths and virtues. For example, culture, religion, or political persuasion may be counted among the contextual factors that could influence character (Park, 2004).

Peterson and Seligman (2004) argued that one must discriminate between talents and skills, and virtues and character strengths. Talents and skills seem more innate, more immutable, and less voluntary than positive traits, and while talents and skills may be considered strengths, they are not moral strengths. Moreover, unlike positive traits, talents, and skills – e.g., abstract reasoning or playing tennis – seem to be valued more for their tangible consequences – e.g., success or significant financial income – and consequently, it can be considered whether the talents or skills have been misused or well used. In this sense, it is common to hear the criticism that someone wasted his or her talent or skill – e.g., engaged in whatever activity would give him or her a quick income rather than developing his or her talent. However, it is uncommon to hear criticism that someone did nothing with their goodness or integrity.

Character is composed of various elements at different levels of abstraction (Peterson & Seligman, 2004). The most abstract components are the virtues, the core characteristics valued by religious writers and moral philosophers. The next level of abstraction corresponds to character strengths, which are the psychological ingredients – processes or mechanisms – that define the virtues, the distinguishable pathways by which we display a given virtue. For example, the virtue of wisdom is manifested in the character strengths curiosity, love of knowledge, open-mindedness, creativity, and perspective, which have in common that they involve the acquisition and use of knowledge (Peterson & Seligman, 2004). Character strengths should not be viewed as isolated mechanisms of automatic effects on behavior; rather, virtuous activity involves the choice of virtue for its own sake, considering a justifiable life project that leads to human excellence or flourishing (Park et al., 2004). The lowest level of abstraction is composed of situational themes that are the specific habits that lead people to manifest a strength in a given situation. Although this is the lowest level of abstraction connecting us to the manifestation of character strengths in specific situations, it is the most elusive and diverse aspect because of an overly broad list of situational themes related, for example, to families or military academies. In this sense, there is a wide variety of ways in which moral excellence can be manifested in a parent or a cadet.

Character Strengths in the Military Context

From the point of view of positive psychology, a social group that becomes especially relevant is the military population. This is because their beliefs and doctrinal bases hold that the military leader must have virtues or personal conditions, such as courage, integrity, responsibility, and enthusiasm, which are similar to the character traits studied in positive psychology. The importance given by the military to positive traits is not left undetermined but is materialized, in such practices as the evaluation of the character traits of students at the military academy. Indeed, unlike most civilian universities, the military academy produces a character trait rating that is included as part of the overall evaluation of each cadet’s performance and that plays a significant role because it may have implications for his or her permanence within the military educational institution.

A strong belief in the military is that moral virtues are important characteristics for effective military leadership. This idea is not only embodied in the military doctrine, which states that character and values are critical for successful military leadership (Ejército Argentino, 1990), but is also held by military officers and students (Casullo & Castro Solano, 2003). For example, the military doctrine of the Argentine Army (1990) explicitly mentions that the future military leader must possess specific character traits, like perseverance, initiative, and integrity. The character traits mentioned can be conceptually linked, with varying levels of precision, to the positive traits as defined and classified by Peterson and Seligman (2004). Similarly, (Matthews et al., 2006) asserted that the US Army doctrine (Department of the Army, 1999), explicitly lists character traits of importance in military leadership. The authors have pointed out that because the military doctrine does not provide operational definitions of character or values, the concepts in the military doctrine are not directly comparable to the formal constructs of character virtues and strengths defined by Peterson and Seligman (2004). However, the authors recognized that at least half of the positive traits in their classification are cited in the military doctrine. Some empirical studies have advanced in verifying this significant belief, and there is empirical evidence from the perspective of positive psychology (Boe et al., 2015; Matthews et al., 2006).

Within the framework of positive psychology, several empirical investigations have been conducted among the military population, including the study of the 24 character strengths of Peterson and Seligman’s (2004) character classification. Different aspects linked to these morally valued traits are described below.

Relevance

A group of experts and military personnel showed which character strengths they considered relevant to be successful as a military leader. Experts and military members of the Norwegian Military Academy suggested that nine of the character strengths apply to professional performance: leadership, integrity, persistence, courage, teamwork, open-mindedness, social intelligence, self-regulation, and creativity (Boe et al., 2015).

Cadets and Civilian Students

There are differences between civilian and military university students in character strengths (Cosentino & Castro Solano, 2012). In a sample of Argentinian male students matched in age and career stage, Army cadets presented higher levels of spirituality, social intelligence, love, prudence, humility, self-regulation, and leadership, and lower levels of appreciation of beauty and excellence, controlling for social desirability effect. In another research, differences were found between first-semester West Point cadets and a group of US civilian students (Matthews et al., 2006). West Point cadets had higher scores compared to civilians on courage, prudence, teamwork, curiosity, fairness, honesty, hopefulness, perseverance, leadership, humility, self-regulation, social intelligence, and spirituality, but lower scores on the appreciation of beauty and excellence. In both studied populations, not only did the cadets present higher levels of character strengths compared to civilians, but they also coincided in that the cadets presented higher levels of social intelligence, prudence, humility, self-regulation, and leadership strengths, while the appreciation of beauty and excellence presented lower levels compared to civilian students from the same country.

Cadets from Different Countries

There are also differences in the level of character strengths among first-semester cadets from different countries (Matthews et al., 2006). A comparison between US and Norwegian cadets showed that US cadets had higher levels of all character strength scores, except for forgiveness and vitality, for which no differences were detected.

Cadets With and Without Military Family

Also, there are differences in character strengths among military students whose parents are military personnel, compared to those who do not come from a military family background (Gosnell et al., 2020). In the sample of cadets at West Point Military Academy, the United States, the cadets who came from a family with military parents presented less perseverance and self-regulation compared to cadets who came from a non-military family.

Cadets at the Beginning and End of the Academy

There are differences between first and last year cadets in character strengths (Cosentino & Castro Solano, 2012). Final year cadets in the Argentine Army academy presented higher levels of forgiveness, but lower kindness and teamwork, controlling for social desirability, compared to first-year cadets.

Changes Over Time in Cadets

There are character strength changes over time in the military institution. In a sample from the United States Coast Guard Academy, decreases and increases were determined in strength levels by comparing last year to first-year students of the academy (Giambra, 2018). Ranked from largest to smallest, the decreases in the last year in comparison to the first year were observed in citizenship, spirituality, hope, love, perseverance, vitality, humor, fairness, leadership, curiosity, honesty, and self-regulation. Increases, ordered from highest to lowest, were found in appreciation for beauty and excellence, fairness, and love of knowledge.

Academic and Military Performance

Character strengths are associated with the academic and military performance of military cadets (Cosentino & Castro Solano, 2012). In first-year Army cadets, the character strength love for learning had a positive relationship, while forgiveness had a negative relationship with academic performance. In senior cadets, persistence and creativity were positively related, while humility and teamwork were negatively related to academic performance. In first-year cadets, leadership and vitality were positively related, while the appreciation of beauty and excellence and fairness were negatively associated with performance. Persistence and vitality were positively related, while self-regulation was negatively related to performance in military subjects in the senior year. There were also differences in the relationship between character strengths and academic and military performance among cadets with military parents compared to those with non-military parents (Gosnell et al., 2020). The relationships of character strengths with academic and military performance were similar within each of the student types, but the profile of associations was different between groups. For example, in cadets with military parents, perseverance, self-regulation, and prudence were positively related, while love was negatively related to academic and military performance; and humility was positively related to military performance. In cadets with non-military parents, forgiveness, vitality, gratitude, fairness, curiosity, and prudence were positively related to academic performance. The relationship of strengths with military performance showed a similar profile.

Summary

Positive psychology has been around for about 20 years, and there is a classification of character strengths that has prompted research on morally valued traits for less than 20 years. Several investigations have been conducted on the military population, which concluded that character strengths are linked to various outcomes and group differences. Most of the research reviewed here shows studies with the military cadet population. However, studies including the 24 character strengths from Peterson and Seligman’s (2004) VIA classification on military personnel serving as officers are scarce. Because character strengths have been useful in describing and comparing characteristics and outcomes in cadet populations, we hope that researchers use the VIA classification of 24 character strengths to study officers’ military career development, performance in combat, or search and rescue activities.

Further Reading

Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification. Oxford University Press.

References

Allport, G. W. (1921). Personality and character. Psychological Bulletin, 18(9), 441–455. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0066265.

Allport, G. W., & Vernon, P. E. (1930). The field of personality. Psychological Bulletin, 27(10), 677–730. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0072589.

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, text revision (4th ed.).

American Psychological Association. (1999). The APA 1998 annual report. American Psychologist, 54(8), 537–568. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.54.8.537.

Barenbaum, N. B., & Winter, D. G. (2008). History of modern personality theory and research. In Handbook of personality: Theory and research (3rd ed., pp. 3–26). The Guilford Press.

Boe, O., Bang, H., & Nilsen, F. A. (2015). Selecting the most relevant character strengths for Norwegian army officers: An educational tool. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 197, 801–809. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.07.188.

Carr, A. (2004). Positive psychology: The science of happiness and human strengths. Psychology Press.

Casullo, M. M., & Castro Solano, A. (2003). Concepciones de civiles y militares argentinos sobre el liderazgo. [Conceptions of leadership among military and civil Argentines.]. Boletín de Psicología (Spain), 78, 63–79.

Cawley, M. J., III, Martin, J. E., & Johnson, J. A. (2000). A virtues approach to personality. Personality and Individual Differences, 28(5), 997–1013. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(99)00207-X.

Cosentino, A. C., & Castro Solano, A. (2012). Character strengths: A study of Argentinean soldiers. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 15(1), 199–215. https://doi.org/10.5209/rev_SJOP.2012.v15.n1.37310.

Dahlsgaard, K., Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2005). Shared virtue: The convergence of valued human strengths across culture and history. Review of General Psychology, 9(3), 203–213. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.9.3.203.

Department of the Army. (1999). Field manual no. 22–10. Army leadership: Be, know, do.

Ejército Argentino. (1990). Manual del Ejercicio del Mando. MFP-51-13. [Command exercise manual].

Gable, S. L., & Haidt, J. (2005). What (and why) is positive psychology? Review of General Psychology, 9(2), 103–110. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.9.2.103.

Giambra, L. M. (2018). Character strengths: Stability and change from a military college education. Military Psychology, 30(6), 598–608. https://doi.org/10.1080/08995605.2018.1522925.

Gosnell, C. L., Kelly, D. R., Ender, M. G., & Matthews, M. D. (2020). Character strengths and performance outcomes among military brat and non-brat cadets. Military Psychology, 32(2), 186–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/08995605.2019.1703434.

Hunter, J. D. (2001). The death of character: Moral education in an age without good or evil. Basic Books.

Linley, P. A., Joseph, S., Harrington, S., & Wood, A. M. (2006). Positive psychology: Past, present, and (possible) future. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 1(1), 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760500372796.

Matthews, M. D., Eid, J., Kelly, D., Bailey, J. K. S., & Peterson, C. (2006). Character strengths and virtues of developing military leaders: An international comparison. Military Psychology, 18(Suppl), S57–S68. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327876mp1803s_5.

McCullough, M. E., & Snyder, C. R. (2000). Classical source of human strength: Revisiting an old home and building a new one. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 19(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2000.19.1.1.

Nicholson, I. A. M. (1998). Gordon Allport, character, and the “culture of personality,” 1897–1937. History of Psychology, 1(1), 52–68. https://doi.org/10.1037/1093-4510.1.1.52.

Park, N. (2004). Character strengths and positive youth development. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 591, 40–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716203260079.

Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2009). Strengths of character in schools. In R. Gilman, E. S. Huebner, & M. J. Furlong (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology in schools (pp. 65–76). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

Park, N., Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Strengths of character and well-being. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 23(5), 603–619. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.23.5.603.50748.

Peterson, C. (2006). A primer in positive psychology. Oxford University Press.

Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification. Oxford University Press.

Seligman, M. E. P. (2002). Positive psychology, positive prevention, and positive therapy. In Handbook of positive psychology (pp. 3–9). Oxford University Press.

Seligman, M. E. P., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology: An introduction. American Psychologist, 55(1), 5–14. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.5.

Seligman, M. E. P., & Peterson, C. (2003). Positive clinical psychology. In A psychology of human strengths: Fundamental questions and future directions for a positive psychology (pp. 305–317). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10566-021.

World Health Organization. (1992). The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: Clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Section Editor information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this entry

Cite this entry

Cosentino, A.C., Solano, A.C. (2023). Character Strengths and Its Utility for Military Leadership: A View from Positive Psychology. In: Sookermany, A.M. (eds) Handbook of Military Sciences. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-02866-4_102-1

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-02866-4_102-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-02866-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-02866-4

eBook Packages: Springer Reference Political Science and International StudiesReference Module Humanities and Social SciencesReference Module Business, Economics and Social Sciences