Abstract

In recent times, the rapid growth in mobile subscriptions and the associated demand for high data rates fuels the need for a robust wireless network design to meet the required capacity and coverage. Deploying massive numbers of cellular base stations (BSs) over a geographic area to fulfill high-capacity demands and broad network coverage is quite challenging due to inter-cell interference and significant rate variations. Cell-free massive MIMO (CF-mMIMO), a key enabler for 5G and 6G wireless networks, has been identified as an innovative technology to address this problem. In CF-mMIMO, many irregularly scattered single access points (APs) are linked to a central processing unit (CPU) via a backhaul network that coherently serves a limited number of mobile stations (MSs) to achieve high energy efficiency (EE) and spectral gains. This paper presents key areas of applications of CF-mMIMO in the ubiquitous 5G, and the envisioned 6G wireless networks. First, a foundational background on massive MIMO solutions-cellular massive MIMO, network MIMO, and CF-mMIMO is presented, focusing on the application areas and associated challenges. Additionally, CF-mMIMO architectures, design considerations, and system modeling are discussed extensively. Furthermore, the key areas of application of CF-mMIMO such as simultaneous wireless information and power transfer (SWIPT), channel hardening, hardware efficiency, power control, non-orthogonal multiple access (NOMA), spectral efficiency (SE), and EE are discussed exhaustively. Finally, the research directions, open issues, and lessons learned to stimulate cutting-edge research in this emerging domain of wireless communications are highlighted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The exponential growth of wireless network service users worldwide orchestrates the need to deploy novel enabling technologies to satisfy billions of data-hungry applications [1]. In recent times, the emergence of the Internet of Things (IoT) has ushered in new-age internet-enabled smartphones and machine-to-machine communications (M2M) for the growing mobile users [2]. However, the current network infrastructure is already overstretched, and there is a need for novel technologies to improve the existing wireless network architecture [3]. From managing security and privacy challenges, network spectrum issues, traffic spikes, complex network configuration, prohibitive operating costs, network failure, to hardware compatibility issues and more, the ubiquitous fifth-generation (5G) wireless network architecture needs to be enhanced to accommodate these growing concerns optimally [4, 5]. Recently, key enabling technologies for the envisioned beyond 5G and 6G wireless systems have been proposed [6,7,8,9]. Interestingly, these enablers include cell-free massive MIMO (CF-mMIMO) technology [10,11,12], mmWave communication [13,14,15], terahertz communication [16,17,18], quantum communication [19, 20], directional beamforming [21], reconfigurable intelligent surfaces (RIS) [22,23,24], and more.

The concept of CF-mMIMO introduced in [25] presents a promising alternative to guarantee high quality of service (QoS) to all UEs. CF-mMIMO leverages the idea of small-cells (SC), massive MIMO, and user-based joint transmission coordinated multi-point (JT-CoMP) [26] to deal with inter-cell interference [27]. Additionally, CF-mMIMO provides massive macro-diversity to mitigate path loss [28] via minimizing the adverse effects of spatially correlated fading and shadowing [29]. In this case, several ubiquitous access points (APs) with single or multiple antennas jointly serve a smaller number of distributed UEs over the coverage area in time-division duplex (TDD) mode [30]. CF-mMIMO has been described as an embodiment of network MIMO and is regarded as an alternative network MIMO [31]. Compared to the fully distributed SC system and massive cellular MIMO, CF-mMIMO has improved performance under several practical conditions, including but not limited to favorable propagation and channel hardening with spatially well-separated UEs and APs. This results in increased macro-diversity gain from the low distance between UEs and APs [3, 32, 33].

Currently, there is a growing interest in the implementation of sustainable and greener CF-mMIMO systems [34] to boost the energy efficiency (EE) [35, 36] of wireless systems, offset the power consumption cost [37], and minimize the environmental impacts of wireless systems [38]. Several optimization techniques, EE-saving algorithms, and robust power control models [39, 40], such as energy cooperation [41], reconfigurable intelligent surface (RIS) [23, 42, 43], and more, have been explored. Combining CF-mMIMO and simultaneous wireless information and power transfer (SWIPT) technique is considered to drive energy-limited user devices and improve the EE of next-generation wireless networks [44,45,46]. Given that several APs and several users are involved in a CF system [47], the deployment cost and energy consumption may rise, and more energy resources [48, 49] would be required. In order to realize CF-mMIMO in practice, carrier frequency and sampling rate offsets, In-phase/quadrature-phase (I/Q) imbalance, phase noise, and analog-to-digital converter distortions need to be examined [50, 51]. Toward this end, this paper provides an extensive survey on the areas of application of CF-mMIMO in next-generation wireless communication systems. A comprehensive layout of the paper is presented in Fig. 1. Furthermore, different massive MIMO-based solutions, massive cellular MIMO, and network MIMO are examined critically. The design and system configurations, system modeling, application scenarios, potentials, and associated challenges of CF-mMIMO are discussed extensively. Additionally, open research issues, lessons learned, and future research directions are outlined.

This survey is focused on applying CF-mMIMO in 5G and beyond 5G (B5G) wireless networks. The key highlights of the survey are outlined as follows.

-

1.

We present a background on the evolution of CF-mMIMO in emerging wireless communication systems.

-

2.

We present an overview of cellular massive MIMO, network massive MIMO, and CF massive MIMO, highlighting their areas of application, strengths, limitations, and performance comparison of these architectures with reference to key design metrics, interference management, channel hardening, and SE, among others.

-

3.

We examine the configuration details and system modeling of CF-mMIMO, emphasizing the uplink/downlink (UL/DL) pilot-aided channel estimation, UL/DL training, channel hardening, and outage probability.

-

4.

We highlight key areas of application of CF-mMIMO such as in SWIPT, power control, NOMA, SE, and EE.

-

5.

We present key research findings and current trends in CF-mMIMO, highlighting their focus, coverage, prospects, and limitations.

-

6.

We highlight open research issues, future research directions, and key take-away lessons on CF-mMIMO deployment in 5G and B5G wireless networks.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. The literature review is presented in the “Related work” section. A comprehensive description of the traditional MIMO architecture, massive cellular MIMO, network MIMO, and CF-mMIMO is presented in the “Overview of massive MIMO systems” section. The “System model of cell-free massive MIMO” section offers a detailed account of the CF-mMIMO system modeling and configuration. The application of CF massive MIMO in channel hardening, NOMA, EE, and more are discussed in the “Areas of application of cell-free massive MIMO” section. Open research issues and lessons learned are highlighted in “Open research issues and lessons learned” section. Finally, the “Conclusions” section gives a concise conclusion to the paper.

Related work

Cell-free massive MIMO has attracted considerable research interest in the past decade, and it is currently regarded as a key 5G and beyond 5G physical layer technology [52,53,54,55]. The authors in [56] provide an in-depth exposition into simulation platforms and insightful schemes for emerging 5G interfaces. An extensive overview of several solutions for 5G infrastructures including, but not limited to massive MIMO, millimeter-wave (mmWave), NOMA, and also the latest achievements on simulator capabilities, are clearly outlined. Also, artificial intelligence (AI)-based discontinuous reception (DRX) technique for greening 5G enabled devices have been proposed in [57]. The proposed mechanism significantly outperforms the conventional long-term evolution (LTE)-DRX technique in efficient energy savings. In recent times, the use of deep learning techniques to perform power control in wireless communication networks has been studied in [58,59,60]. Reference [61] advocate using deep neural networks to perform joint beamforming and interference coordination at mmWave.

Additionally, the authors in [62] consider incorporating channel hardening in CF-mMIMO using stochastic geometry and evaluated the potential constraints to its practical implementation. It suffices that the channel hardening effect is more noticeable in massive cellular MIMO than in CF-mMIMO and depends mainly on the number of antennas per AP and the pathloss exponent of the propagation environment [63]. Fortunately, the authors [64] have shown that significant improvement in channel hardening is achievable with the normalized conjugate beamforming (NCB) precoder compared to the conjugate beamforming (CB) scheme. The works [65,66,67] characterized the coexistence of CF-mMIMO and SWIPT utilizing the Poisson point process (PPP) model.

Furthermore, an insight into the achievable harvested energy, channel variations due to fading and path loss, and UL/DL rates in closed form are considered [68, 69]. The detrimental effects of pilot contamination on the performance of CF-mMIMO are highlighted in [70, [1]. The authors in [53] proposed allocating pilot power for each user in the network to palliate this defect. Interestingly, interference management and joint user association aimed at minimizing cell-edge effects are studied [70]. References [11, 71] have reported novel scalable and distributed algorithms used for initial access and cooperation cluster formation in CF-mMIMO. The authors also proposed scalable signal-to-leakage-and-noise ratio precoding to address the scalability issues in CF-mMIMO. Currently, federated learning (FL) frameworks are introduced in [72, 73], and FL optimization techniques have been presented in [74,75,76]. A detailed account recapitulating the impact of hardware impairments (HI) on the performance of CF-mMIMO is characterized [48]. By employing a hardware scaling law, the impact of HI on APs is shown to vanish asymptotically. The authors in [77] analyzed the UL and DL CF-mMIMO performance under the classical HI model to gain further insights.

Most of the literature provides valuable information on massive MIMO deployment in 5G wireless networks. Though some of these papers present several aspects of CF-mMIMO, there is no detailed study on CF-mMIMO systems that captures entirely cellular massive MIMO, network MIMO, and CF-mMIMO system modeling, architecture, strengths and limitation, and applications in terms of SWIPT, channel hardening, hardware efficiency, power control, NOMA, SE, and EE. To this end, the need for a comprehensive paper covering the aspects mentioned above of CF-mMIMO is vitally important. Therefore, the current paper presents an extensive survey on CF-mMIMO as a candidate enabler for 5G and B5G wireless networks. Specifically, the limitations of some selected literature are outlined, and the contributions of the current paper are highlighted, as presented in Table 1.

Overview of massive MIMO systems

The concept of massive MIMO has received considerable attention due to its deployment to meet the demands of wireless capacity and higher data rates [89]. Massive MIMO offers improved spectral and energy efficiency and adopts optimal signal processing schemes [90]. Moreover, massive MIMO can spatially multiplex many user equipment (UE) by using many phase-coherent transmitting/receiving antennas, thus suppressing inter-cell and intra-cell interference [91, 92]. These unique features have revitalized studies leading to the discoveries of several massive MIMO solutions [93]. Massive MIMO technology, empowered with several antennas at each cell site, offers tremendous improvements in the radiated EE, power efficiency, and SE compared to the traditional MIMO systems [94, 95]. Moreover, by operating in either a centralized or distributed fashion, favorable propagation facilitates the realization of near-optimal linear processing [96]. Motivated by the benefits mentioned above, various massive MIMO-based solutions significantly gained traction in academia and industry [97]. A brief discussion on cellular mMIMO, network MIMO, and CF-mMIMO focusing on their architectures, strengths, and applications are presented in the following subsections.

Cellular massive MIMO

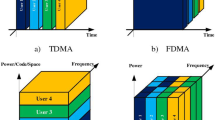

Massive MIMO time-division duplex (mMIMO-TDD) systems have been reported to boost the throughput of wireless networks [83, 86]. Since the multiple antennas used in mMIMO-TDD are much smarter, it presents a practical means to outperform partial multiuser MIMO (MU-MIMO) systems. BS antennas could be substantially larger than the number of transmitter terminals. Recently, the attractive features of cellular networks, including exploiting channel reciprocity, especially as more antennas do not necessarily lead to a corresponding increase in the feedback overhead, have been investigated. The traditional cell-size shrinking technique is eliminated via the installation of extra antennas to existing cell sites. Furthermore, UL and DL transmit powers are considerably reduced due to increased antenna aperture and coherent combining. Nonetheless, cellular networks face significant challenges, including estimating the criticality of coherent channels, bandwidth, and interference limitations. Additionally, the substantial cost associated with a large number of transmitting/receive chains and power amplifiers is a major setback. An illustrative description of a typical cellular massive MIMO system is given in Fig. 2. The mobile station (MS) is connected to a central base station (BS) in each cell.

Network MIMO

Network MIMO system, which allows for coordination of a set of APs that jointly serve all users in the network, has often been hailed as an exciting alternative to achieving the capacity limit of cellular networks [98, 99]. Network MIMO or multicell MIMO signaling is considered a potential physical layer technique for 5G wireless networks. A plethora of interfering transmitters share user messages in a network MIMO system and enable joint precoding to be performed. Additionally, network MIMO could be referred to as cooperative communications used to improve the interference-limited performance of cellular networks. Specifically, by jointly designing the DL beams to multiplex multiple users spatially, intra-cluster interference can be eliminated. This concept has recently been introduced under a new network structure named CF massive MIMO [3]. It is considered a key enabling technology for 5G and beyond 5G wireless systems. Besides, the cell-edge problem inherent in cellular massive MIMO is eliminated, and all antennas jointly serve all users (UEs). Figure 3 presents the architecture of a typical network MIMO system.

Cell-free massive MIMO

The cellular topology has been the traditional way of covering the subscribers in a given geographical area with wireless network service for many decades. Each BS serves a given set of UEs using highly directional beamforming techniques [94]. This network topology has shown desirable performance gains, spectral efficiency, and energy efficiency [100,101,102]. However, the technology inevitably limits further performance improvements due to inter-cell interference, high QoS variations, and hand-offs [78, 103]. In order to address this problem, a viable option is to eliminate the inherent cell characteristics and take a considerable number of distributed APs densely deployed over a given coverage area to serve a smaller number of UEs optimally [53]. This novel communication architecture is described as cell-free massive MIMO, and it has been identified as a candidate enabling technology for future wireless communication systems [83, 104].

Currently, key disruptive technologies have been deployed to cater to throughput, coverage, EE, and ubiquity requirements of next-generation wireless networks. In particular, having multiple antennas at the APs for several users has been observed as a promising technique to boost the multiplexing gain and enhance the SE in CF massive MIMO [55, 80]. Recently, power domain-centric NOMA integrated with CF-mMIMO emerged as a viable solution to address the conflicting demands on high SE, EE, high reliability with user-fairness, increased connectivity, and reduced latency in 5G wireless networks [105,106,107]. In CF-mMIMO, the number of simultaneously served users can be increased by supporting the users to utilize the same time-frequency resource effectively and invoking superposition-coded transmission and successive interference cancelation (SIC) decoding [108,109,110].

Cell-free massive MIMO leverages a distributed antenna system’s unique features, coordinates beamforming, joint transmission, and scheduling to provide multiuser interference suppression and achieve stronger diversity gains. Moreover, due to the well-designed network topology, CF-mMIMO allows for favorable propagation and high quality of service throughout the coverage area [25, 52, 103, 111]. Compared to conventional cellular networks, some of the fascinating features of CF networks include uniform signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) with smaller variations, improved interference management, increased SNR due to coherent transmission [12], high EE, high SE, low latency, low complex linear processing, minimal power consumption, flexible and cost-efficient deployment, and high reliability, among others [9, 103]. Figure 4 presents a pictorial representation of a CF-mMIMO network, and Table 2 presents a performance comparison among cellular massive MIMO, network MIMO, and CF-mMIMO. According to its performance level, several critical performance metrics are selected, and each metric has been weighted (in percentage), as discussed in Section 5 of the current paper. Last, a pictorial comparison of cellular mMIMO and CF-mMIMO is shown in Fig. 5. For the cellular condition, hundreds and even thousands of BS antennas are selected to serve UEs within disjoint cells, thus achieving considerable throughput and coverage improvement. However, for the CF scenario, a plethora of geographically distributed single APs are chosen to serve a smaller number of UEs. The coverage area is not divided into disjoint cells leading to a CF network where signals from surrounding APs only influence each UE. The distributed AP antennas are connected via a fronthaul network to one or multiple central processing units (CPUs), facilitating effective coordination.

System model of cell-free massive MIMO

The CF-mMIMO network arbitrarily distributed over a wide coverage area operating on a one-time frequency resource is discussed in this framework. Let there be K UEs and M randomly located APs, each equipped with Nap antennas, where Nap≥1. It is often assumed that M ≫ K. Besides, all APs are connected through an unlimited backhaul network to edge-cloud processors, called the CPU. Data-decoding is performed, ensuring that the UEs’ coherent joint transmission and reception in the coverable area are enabled. Remarkably, the pathloss between a user and any AP antenna is unique. The pathloss matrix possesses distinct diagonal elements, and as a result, performance analysis is generally challenging and considerably different from related prior works. TDD protocol with channel reciprocity and a single data stream transmitted per UE is assumed. The communication protocol is usually divided into several phases. These include UL training, UL payload data transmission, DL training, and DL payload data transmission. For the overview of the system model of CF-mMIMO networks captured in this survey, a concise list of relevant mathematical notations used and their meanings are presented in Table 3.

First, by taking into consideration a DL CF massive MIMO system, let a set of BSs ß ≜ {1, …, B}, each equipped with M antennas serves a set of UEs К ≜ {1, …, K},each loaded with N antennas. Moreover, let Hb, k ∈ ℂM × Ndenote the UL channel matrix between BS b ∈ ß and UE k ∈ К, while \( {H}_k\triangleq {\left[{H}_{1,k}^T,\dots, {H}_{B,k}^T\right]}^T\in {\mathbb{C}}^{BM\times N} \) represents the global UL channel matrix seen by UE k. More so, let Yb, k ∈ ℂM × 1denote the BS-Specific precoding vector utilized by BS b for UE k, while \( {Y}_k\triangleq {\left[{Y}_{1,k}^T,\dots, {Y}_{B,k}^T\right]}^T\in {\mathbb{C}}^{BM\times 1} \) represents the global precoding vector utilized UE k.

Thus, the received signal at UE k reads as (1)

where gk~CN(0, 1) denotes the transmit data symbol for UE k, and \( {z}_k\sim CN\ \left(0,{\sigma}_k^2{I}_N\right) \) represents the average AWGN at UE k. When pkis collected, UE k employs the combining vector qk ∈ ℂN × 1. The resulting signal-to-interference-plus-noise ratio (SINR) [118] is given by (2)

In addition, the sum rate is expressed as R ≜ ∑k ∈ Klog2(1 + SINRk). Next, the realistic pilot-aided channel state information (CSI) acquired at the BSs, and the UEs are considered.

Uplink pilot-aided channel estimation

Let the effective UL channel vector between UE k and BS b be denoted by db, k ≜ Hb, kqk ∈ ℂM × 1. Likewise, let the pilot assigned to UE k be denoted by lk ∈ ℂρ × 1, where || lk||² = ρ. In this phase, each UE k jointly transmits its pilot precoded with its combining vector and is expressed as (3)

Thus, for each BS b, \( {X}_b^{UL-1} \)is given by (4) and (5)

where \( {Z}_b^{UL_{\bar{\mkern6mu}}1}\in {\mathbb{C}}^{M\times \uprho} \) denotes the AWGN at BS b having elements distributed as Ϲ (\( 0,{\sigma}_b^2\Big) \). Likewise, the LS estimate of db, k is given by (6) and (7)

Downlink pilot-aided channel estimation

Let the effective DL channel vector between all the BSs and UE k be denoted by \( {h}_k\triangleq {\sum}_{b\in \mathrm{\ss}}{H}_{b,k}^H{y}_{b,k}\in {\mathbb{C}}^{N\times 1} \). In this phase, each BS jointly transmits a superposition of pilots after they have been precoded with the corresponding precoding vector and is expressed as (8)

Thus, for each UE k, \( {X}_k^{DL} \) is given by (9)

where

\( {Z}_k^{DL}\in {\mathbb{C}}^{N\times \uprho} \)denotes the AWGN at UE k with elements distributed as Ϲ (\( 0,{\sigma}_k^2\Big) \). Likewise, the LS estimate of hkis given by (10) and (11)

There exist several pilot-based channel estimators, namely LS estimator, minimum mean-squared error (MMSE), element-wise minimum mean-squared error (EW-MMSE), phase-aware minimum mean-squared error (PA-MMSE), and linear MMSE. Table 4 presents a summary of pilot training-based channel estimators [119]. Next, the UL training phase, DL training phase, and outage probability of the communication protocol are considered.

Uplink training

In the uplink training phase, the UEs send UL training pilot sequences to allow channel estimation at the APs. The uplink training phase also applies to the user-centric (UC) massive MIMO architecture. Let τc represent the length of the channel coherence time in discrete-time samples and τs represent the length of the UL training phase, also in discrete-time samples. At all times, τs < τc. The matrix has on its rows the pilot sequences transmitted by the kth UE is denoted by \( {\varnothing}_k\in {C}^{s\times {\tau}_s} \). While the rows of ∅k are assumed to be orthogonal, i.e., \( {\varnothing}_k{\varnothing}_k^D={I}_S \), assuming there is no orthogonality for the pilot sequences directed to other UEs. Of course, by employing orthogonal pilot tout court, a robust system to the effects of pilot contamination is achievable. However, the peak value of the product KS that can be taken in the channel coherence time would be primarily limited. Thus, we define the NAP × τs dimensional matrix Xm by (12)

where Fk, m = Dk, mLk, Ym denotes the matrix of thermal noise samples. Next, we explore the structure of the LMMSE channel estimator briefly. Defining parameters, xm = vec(Xm), ym = vec(Ym), fk, m = vec(Fk, m), the vectorized model is given as (13)

where \( {R}_k={\varnothing}_k^T\otimes I. \)We process xm by a matrix \( {Q}_{k,m}^D \), i.e., \( {\hat{f}}_{k,m}={Q}_{k,m}^D{x}_m \). Thus, the MSE is obtained as (14)

In this case, the gradient of the MSE concerning the complex matrix \( {Q}_{k,m}^{\ast } \) is assumed to be equal to zero. Solving for Qk, m,the LMMSE estimator is given by (15)

Downlink training

In this section, the scalable beamforming training scheme is adopted. Let τv, l denote the length of the DL training duration per coherence interval; it suffices that τv, l < τ − τu, l. By exploiting the channel estimates \( \left\{\hat{h}m{k}^{\acute{\mkern6mu}}\right\} \), and beamforming it to all users, the mth AP precodes the pilot sequences \( {\varphi}_{k^{\acute{\mkern6mu}}}\in {\mathbb{C}}^{\tau_{v,l}\times 1},{k}^{\acute{\mkern6mu}}=1,\dots, K. \) Thus, the τv, l × 1 pilot vector wm, l sent from the mth AP is obtained as (16)

where σv, l is the normalized transmit SNR per DL pilot symbol and {φk} assume mutual orthonormality i.e. \( {\varphi}_k^D{\varphi}_{k^{\acute{\mkern6mu}}}=0, \)for k´ ≠ k, and ‖φk‖2 = 1. This requires that τv, l ≥ K. The kth user receives correspondingly, τv, l × 1 pilot vector which is given by (17)

where yvl, k denotes a vector additive noise at the kth user. The effective channel gain rkk, k = 1, …, K is estimated via the processing of the received pilot first by the kth user as (18)

where \( {\eta}_{l,k}\triangleq {\mathit{\mathsf{\varphi}}}_{\mathit{\mathsf{k}}}^{\mathit{\mathsf{D}}}{\boldsymbol{\mathsf{y}}}_{\mathit{\mathsf{vl}},\mathit{\mathsf{k}}}\sim CN\left(0,1\right) \). Given \( {\overset{\check{} }{x}}_{vl,k}, \) linear MMSE estimation of rkkis performed, which is obtained as (19)

Outage probability

Obtaining the exact expression for outage probability is quite challenging due to the computational complexity in determining the cumulative distribution function (CDF) of the SINR at the APs [120]. The only exception for massive MIMO systems applies to perfect CSI and identically distributed channels unsatisfied in practice [121, 122]. Therefore, an alternate approach, approximate outage probability, is selected to provide the outage probability of massive MIMO networks where all the APs are collocated. Hence, βmk = βk, γmk = γk, ∀m, k. The outage probability approximation of the kth user is obtained as (20) and (21)

for \( T\le \frac{\rho_u\left(M-1\right){\gamma}_K}{\left(1+{\rho}_u\left({\beta}_K-{\gamma}_K\right)\right)} \) and

for \( T>\frac{\rho_u\left(M-1\right){\gamma}_K}{\left(1+{\rho}_u\left({\beta}_K-{\gamma}_K\right)\right)}, \)

where \( {c}_1^i,{c}_2^i,{c}_3,{c}_4 \) and c5 are given by (22), (23), (24), (25), and (26).

Areas of application of cell-free massive MIMO

The wireless research community has explored the outstanding features of the mutually beneficial combination between CF structure and massive MIMO technology to enable seamless transfer from theory to practical implementation. Of course, significant progress in signal processing, communication, and optimization algorithms developed has further deepened the range of applications of this technology. Table 5 presents a summary of CF massive MIMO application areas alongside their strengths and limitations. A concise account of the past findings and current research trends based on SWIPT, channel hardening, hardware efficiency, power control, NOMA, SE, and EE for the CF-MIMO are detailed in the following subsections.

SWIPT in cell-free massive MIMO

The ultra-high transmission rate of wireless networks has been identified as a significant challenge that decreases the lifetime of battery-powered devices. SWIPT is considered an innovative candidate for the energy-limited environment through energy reclamation. It offers an effective solution to enable a guaranteed energy level and minimize backhaul resources and energy consumption. Compared to traditional massive MIMO, CF massive MIMO presents a new paradigm to boost the performance of SWIPT. A summary of recent advances on SWIPT technology in CF massive MIMO is presented in Table 6.

Additionally, the energy harvest and DL achievable rate for an energy user under a linear scheme are presented. First, for the harvested energy, it is assumed that the harvesting circuitry operates with an efficiency represented as η. With reference to the \( \overset{\sim }{j} \)th user which depicts a typical energy user, the ambient harvested energy \( {E}_{\overset{\sim }{j}} \) during a time slot is obtained as (27)

In this case, the noise factor is neglected to owe to its low comparative strength instead of other terms. As a step further, the DL achievable rate for a typical energy user is derived. The average achievable rate \( {R}_{\overset{\sim }{j}} \) can be expressed as (28)

where \( {\gamma}_{\overset{\sim }{j}} \) denotes the SNR of the \( \overset{\sim }{j} \)-th user and is expressed as (29)

Now, \( {R}_{\overset{\sim }{j}} \) can be modeled as (30)

where \( {E}_{\overset{\sim }{j}} \) is given by (27). Thus, \( {R}_{\overset{\sim }{j}} \) is obtained as (31) after some modifications.

Further, the distribution of \( {E}_{\overset{\sim }{j}} \) is approximated with the Gamma distribution employing moment matching. The scale parameters which define the Gamma distributions are obtained as \( {k}_h={\left(\mathbbm{E}\left[{E}_{\overset{\sim }{j}}\right]\right)}^2/\mathbbm{VAR}\left[{E}_{\overset{\sim }{j}}\right] \) and \( {\theta}_h=\mathbbm{VAR}\left[{E}_{\overset{\sim }{j}}\right]/\mathbbm{E}\left[{E}_{\overset{\sim }{j}}\right] \). Consequently, (31) can be re-modeled as (32)

which can be simplified numerically.

Channel hardening and favorable propagation in cell-free massive MIMO

Two essential virtues that appear in the regime of hundreds or even thousands of antennas: channel hardening and favorable propagation, are defined and analyzed. By increasing BS antennas, the propagation is assumed to happen through a quasi-deterministic flat-fading equivalent channel. In light of the above, the fading channel behaves as though it was not a fading channel (almost deterministically) [50]. This phenomenon is referred to as channel hardening. Also, when the channel directions of two UEs become spatially orthogonal, the inter-user and intra-cell interference vanishes automatically using a relatively simple signal processing technique called maximum-ratio processing (MRP). This desirable property is termed favorable propagation. The channel hardening effect has been exploited by massive MIMO to decrease the problem of small-scale fading in wireless communication systems to guarantee desirable reliability and low latency. However, channel hardening conditions have also been observed and remain valid for CF massive MIMO systems, with reduced pathloss exponent and increased antenna density. Table 7 presents a summary of recent trends and advances on channel hardening in CF-mMIMO systems.

The mathematical representation of channel hardening and favorable propagation in CF massive MIMO is presented. Let djk reflects the propagation channel response between the UE k and AP m. The channel hardening effect is defined as (33)

As a result, the impact of the small-scale fading variations on the communication performance is minimized while the challenge of large-scale fading remains. The degree of channel hardening in CF-mMIMO is dependent mainly on the number of antennas per AP and the geographical AP distribution [12]. The favorable propagation is expressed as (34)

Hardware impairments and pilot transmission in cell-free massive MIMO systems

Using practical systems with perfect hardware components during production could result in enormous energy consumption and prohibitive hardware costs, which are not satisfied in practice. In short, the closer to ideal a hardware transceiver is, the more costly, bulkier, and energy-hungry it becomes. This bottleneck, a trade-off between the quality of hardware components and cost, is usually considered a breakthrough. Nonetheless, this technique inevitably introduces hardware and channel impairments, including amplifier non-linearities, phase noise, I/Q imbalance, and ADC distortions into the system. Analyzing CF massive MIMO under the effects of HI has gained significant research interest. Table 8 presents a summary of progress made in this regard. Additionally, mathematical models of the hardware impairment and pilot transmission are presented.

Hardware impairment model

In order to model the combined effect of hardware distortions, the transmitted/received signal is assumed to be distorted by an additive Gaussian noise [92]. The distorted signal is expressed as (35)

where w refers to the input signal to the non-ideal hardware. Moreover, ξi ∈ [0, 1], i = {t, r} reflects the hardware quality coefficient. The distortion noise is obtained as (36) and is independent of the input signal w.

The term \( \mathbbm{E}\left\{\left|w\right|{}^2\right\}=\mathbbm{E}\left\{\left|{w}_i\right|{}^2\right\} \) indicates the equivalence of the variance of both the input and output signals for the non-ideal hardware device. Besides, the hardware quality is obtained through ξi ∈ [0, 1], where ξi = 1 and ξi = 0 denotes perfect and useless hardware, respectively.

Pilot transmission

In this context, it is assumed that τ-length orthogonal pilots represented as ψk ∈ ℂτ × 1 are assigned to UEs, where τ = K ≤ T, and \( {\psi}_k^D{\psi}_{k^{\acute{\mkern6mu}}}=\delta \left(k-{k}^{\acute{\mkern6mu}}\right) \)for k, k´ ∈ {1, 2, …, K}. As a result, the pilot signal \( \sqrt{\tau {P}_p}{\psi}_k \) is transmitted by UEk, and the signal modeled as (37) is received by the mth AP

where Pp refers to the pilot power, zt, k expressed as (38) accounts for the distortion caused by a non-ideal hardware device, zr, m expressed as (39) denotes the distortion caused by hardware impairment at the mth AP and nm represented as (40) indicates the additive noise [92, 137]

Power control in cell-free massive MIMO

Power control has appeared as a key feature and one of the most impacting algorithms in mobile networks. It entails an intelligent selection of transmitter power output to improve the overall performance of wireless systems. The power control techniques find handy applications in CF massive MIMO to limit the generated interference, minimize pilot contamination, maximize the power of the desired received signal, and provide a more uniform QoS to the UEs. Table 9 presents a survey of various areas of application of power control in CF-mMIMO systems. Furthermore, Table 10 shows a more concise account of power control/algorithms (alternative optimization, successive convex approximation (SCA), GP, bisection, SOCP, fractional, and ML-based techniques) used in solving specific utility optimization problems [119].

Additionally, an insight into different power control policies is highlighted. In particular, the equal transmits power policy, equal receive power policy, and inverse leakage policy are considered. In all policies, it is assumed that \( {G}_{ik}={f}_k^D{V}_i{f}_k \).

-

(1)

Equal Transmit Power Policy: In this policy, the same power is transmitted to each UE i, taking into consideration the power constraints and can be expressed as (41)

where C denotes a constant chosen to satisfy the power constraints. The maximum value of C is obtained as (42)

Thus, the total power pi transmitted to any UE i, for i = 1, …, K, can be written as (43)

-

(2)

Equal Receive Power Policy: This policy ensures that the average received signal power that is conditioned on \( \hat{D} \) remains the same for all UE by selecting power scaling factors. Therefore, piGkk = C,for i = 1, …, K. The constant C is also selected to satisfy the power constraints. After some mathematical analysis, pi can be obtained as (44)

-

(3)

Inverse Leakage Policy: This policy allocates lower powers to UEs to minimize the interference in the system, resulting in higher leakage to other UEs. In this policy, it is assumed that pi is inversely proportional to \( \sum \limits_{k=1,k\ne i}^K{G}_{ki} \). Solving for pi yields (45)

NOMA-aided cell-free massive MIMO

Currently, there is a growing interest in implementing NOMA in 5G and beyond 5G systems due to its attractive SE gains and potential to support low latency massive connectivity. NOMA technique, a paradigm shift from the OMA scheme, primarily seeks to allocate non-orthogonal resources to users to manage interference. Considering the enormous benefits of CF-mMIMO and NOMA, integrating these two techniques is envisioned to reap further gains. Recent research efforts on this hybrid combination are summarized in Table 11.

The channel model of a NOMA-aided CF massive MIMO system is presented. The DL channel between the kth user and the mth AP in the nth cluster, where k ∈ {1, …, K}, m ∈ {1, …, M} and n ∈ {1, …, N} can be expressed as (46)

where ζmnk accounts for the large-scale fading, which changes at a prolonged rate [162]. Besides, the circularly symmetric Gaussian assigned with zero mean unit variance can be written as (47)

Spectral efficiency of cell-free massive MIMO

The need to improve the SE by network service providers owing to an ever-increasing number of users and high rate expectations in B5G wireless networks cannot be overemphasized. Interestingly, massive and dense antennae deployment has been at the forefront, and thanks to its ability to upgrade the BS hardware rather than the deployment of new BS sites. Compared to conventional massive MIMO systems, CF has a great potential of substantially improving the SE by employing additional antennas at users, power allocation, and the receiver filter coefficient design. Table 12 presents certain areas of application of CF massive MIMO in improving the SE.

Additionally, a closed-form expression for the UL SE of CF massive MIMO with the LS estimator is presented. In this context, spatially correlated Rayleigh fading channels are taken into consideration. The received signal ru, k at the CPU is expressed as (48)

where vk depicts the desired signal detected by ru, k. The received signal in (48) can be further expressed as (49)

where the desired signal (DS) is given by (50), the beamforming uncertainty gain (BU) is given by (51), the multiuser interference (UI) is given by (52), and the noise interference (NI) is given by (53).

The UL SINR of the kth user is given by (54)

Thus, the SE is obtained as (55)

Energy efficiency of cell-free massive MIMO

While state-of-the-art technologies are consistently developed to address data, QoS, and capacity demands, issues related to environmental concerns and high-power consumption are escalating rapidly. EE has become an essential criterion in designing future wireless networks, and its importance has been realized even more. The cellular configuration can deliver higher EE, and it is widely recognized as naturally energy-efficient. As a step further, the EE of CF-mMIMO has been characterized by researchers worldwide, and several sophisticated optimization techniques and comprehensive power models have been developed accordingly. Table 13 presents a summary of research efforts and future research directions on the EE of CF-mMIMO.

Furthermore, the total EE model of a CF massive MIMO network is presented. From correspondence [168], the total power consumption can be written as (56)

where PA represents the power amplifier’s power consumption and PC represents the circuit power consumption. The power consumption PA and PC is obtained as (57) and (58), respectively

where ζ reflects the power amplifiers efficiency at each user, Pf denotes the fixed power consumption at each AP, PU accounts for the power required to run circuit components at each user, and Pb, m denotes the backhaul power consumption from the mth AP to the CPU and is expressed in the following [169, 170]

where PBT accounts for the total power to operate the backhaul traffic at full capacity, Rb refers to the backhaul rate between the mth AP and the CPU, and Cb reflects the capacity of the backhaul link between the mth AP and the CPU. More precisely, the backhaul rate Rb can be expressed as (60)

where σm represents the quantization bits of the mth AP. Thus, the total EE is obtained as (61)

Open research issues and lessons learned

The concept of CF massive MIMO has received considerable research efforts to understand its essential features and immense benefits. While significant progress has been made, many open questions, unresolved practical, and various deployment challenges persist, requiring substantial research efforts before realizing its promised gains. Table 14 presents an outline of some research directions in HI, signal detection, EE, channel estimation, pilot contamination, and security and privacy issues. As a step further, we highlight vital lessons learned for future research exploration in the area of CF massive MIMO.

Lessons learned

In this section, a comprehensive summary of lessons learned from this survey is presented. The summary covers CF massive MIMO, mmWave, Terahertz, EE, NOMA, security and privacy, HI, and SWIPT, as outlined briefly.

Lesson one

The current wireless network infrastructure is faced with unprecedented demand for ultra-reliability and higher data rates. CF massive MIMO, where many APs are densely deployed across the entire coverage area linked to a CPU, has been proposed to address this problem. However, there are still issues to contend with in network management, hardware design, and practical implementation of CF-mMIMO.

Lesson two

By a careful analysis of the current 5G wireless systems, employing the highly congested microwave frequency band spanning from about 300 MHz to 6 GHz alongside the use of large-scale antenna arrays may not be sufficient to satisfy the demands for increased throughput, ubiquitous QoS, and ubiquitous connectivity. The so-called mmWave frequency band, though a promising physical layer solution to the envisioned beyond 5G wireless communication network, is susceptible to high molecular absorption. This lends the terahertz band a natural candidate for 6G wireless networks. However, distance is a major problem in terahertz communication. However, the combined use of an ultra-dense wireless network, CF-mMIMO, and the less-congested terahertz band is a crucial enabler to much larger bandwidths and a basic pillar to sustain the SE and EE. Terahertz-enabled CF-mMIMO will be a key enabler for next-generation wireless communication systems.

Lesson three

Compared to earlier generations of wireless communication networks, the total power consumption of 5G and beyond-5G systems have increased greatly. This is primarily due to the higher density of APs, larger bandwidths, and larger antenna numbers, resulting in increased environmental and economic concerns. Thus, EE has become a critical requirement in the design of emerging wireless networks. In order to address this issue, highly comprehensive power models, efficient energy management strategies, and more sophisticated optimization techniques are required. Specifically, these systems may be enabled with energy harvesting and energy exchange capabilities. The grid source will be incorporated to compensate for the random and intermittent nature of the harvested energy owing to uncontrollable environmental conditions. Also, the possibility of turning off inactive APs is another useful technique to improve the overall EE of CF massive MIMO systems.

Lesson four

An indispensable candidate technique for next-generation wireless standards is NOMA. The power domain-based concept represents a paradigm shift from OMA, which is fast approaching its fundamental SE limit. An interplay of the distinctive benefits of NOMA and CF massive MIMO is expected to substantially boost the system’s performance with respect to bandwidth efficiency, spectral and energy efficiency, massive connectivity with low latency, and concurrent transmission from multiple users. Nonetheless, the additional hardware complexity due to error propagation and SIC processing is undesirable in practice. In order to tackle the trade-off between complexity and performance (sum rate), high-quality optimization techniques are required.

Lesson five

From the inception of wireless communication networks, security and privacy threats have been a real concern for network operators. With the deployment of 5G and the emerging beyond 5G systems to support billions of connected devices and drive high user mobility, threats to availability and integrity of networks, besides the growing concerns for user privacy, will become more visible. The security threat is envisaged to be greater than ever. There is a need for advanced cryptographic schemes to provide a robust security architecture in wireless networks to protect user privacy. More needs to be done in blockchain technology and quantum communication to tackle the confidentiality and privacy threats posed to future wireless networks.

Lesson six

Deployment of CF massive MIMO depends on multiple antenna elements, which increase the system complexity, energy consumption, and hardware design cost. By using low-cost components, the hardware imperfections increase, which is detrimental to the overall system’s performance. These imperfections consisting of phase noise, I/Q imbalance, amplifier non-linearities, and more are referred to as HIs. There is a need for an optimal trade-off between the quality of the transceiver hardware design and cost. Additionally, there is a need for suitable compensation algorithms to minimize the effects of HI.

Lesson seven

Compared to traditional energy storage methods, SWIPT is considered a potential solution to ease the transmission rate and minimize the energy consumed by battery-powered devices. However, the exponential growth in the number of connected devices coupled with the issues posed by mmWave communication in 5G-aided SWIPT networks presents an entirely new challenge. Therefore, there is a need to find proper allocation schemes to optimize the rate-energy trade-off between information retention and energy allocation.

Conclusions

Cell-free massive MIMO has been proposed as a novel architecture to address the ever-increasing demands for high SE, coverage probability, green output, and uniformly distributed throughput for all network users. In the ubiquitous 5G and the envisioned beyond 5G wireless communication systems, CF-mMIMO enables the deployment of dense APs over a wide network area to communicate with several UEs cooperatively. Motivated by the distinctive benefits of CF-mMIMO, this paper attempted to give a concise survey of the design, application scenarios, potentials, and deployment challenges of this disruptive technology. The system model of CF-mMIMO, covering the UL/DL pilot-aided channel estimation, UL/DL training, and channel hardening, is discussed elaborately. Additionally, the performance characteristics of CF-mMIMO using key design metrics like EE, channel hardening, SE, and more, are discussed extensively. Furthermore, the viable application areas of CF-mMIMO are outlined, and an up-to-date review of key findings and current research trends in CF-mMIMO is presented. Finally, open research issues and key take-away lessons are drawn from the survey to explore this exciting area of wireless communications systems deeply.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing does not apply to this article.

Abbreviations

- 5G:

-

Fifth generation

- 6G:

-

Sixth generation

- ADC:

-

Analog-to-digital converter

- ADMM:

-

Alternating direction method of multipliers

- AI:

-

Artificial intelligence

- ANN:

-

Artificial neural networks

- AP:

-

Access point

- B5G:

-

Beyond 5G

- BE:

-

Bandwidth efficiency

- BS:

-

Base station

- BU:

-

Beamforming uncertainty gain

- CB:

-

Conjugate beamforming

- CDF:

-

Cumulative distribution function

- CF:

-

Cell-free

- CS:

-

Central station

- CPU:

-

Central processing unit

- CSI:

-

Channel state information

- DCC:

-

Dynamic cooperation cluster

- DE:

-

Deterministic equivalent

- DL:

-

Downlink

- DNN:

-

Deep neural network

- DRX:

-

Discontinuous reception

- DS:

-

Desired signal

- ECB:

-

Enhanced bormalized conjugate beamforming

- EE:

-

Energy efficiency

- EMCF:

-

Estimate-multiply-compress-forward

- EPC:

-

Equal power control

- EW-MMSE:

-

Element-wise minimum mean-squared error

- FD:

-

Full-duplex

- FL:

-

Federated learning

- fpZF:

-

Full-pilot zero-forcing

- GP:

-

Geometric programming

- HD:

-

Half-duplex

- HI:

-

Hardware impairment

- IA:

-

Inner approximation

- IoT:

-

Internet of Things

- I/Q:

-

In-phase/quadrature

- JT-CoMP:

-

Joint transmission coordinated multi-point

- LMMSE:

-

Linear minimum mean-squared error

- LOS:

-

Line-of-sight

- LS:

-

Least-square

- LTE:

-

Long-term evolution

- MF:

-

Matched filtering

- MIMO:

-

Multiple input multiple output

- ML:

-

Machine learning

- mMIMO:

-

Massive MIMO

- MMSE:

-

Minimum mean-squared error

- MR:

-

Maximum ratio

- MRC:

-

Maximum ratio combining

- MRT:

-

Maximum ratio transmission

- MS:

-

Mobile station

- M2M:

-

Machine-to-machine

- NCB:

-

Normalized conjugate beamforming

- NI:

-

Noise interference

- NOMA:

-

Non-orthogonal multiple-access

- OBC:

-

Optimal backhaul combining

- OMA:

-

Orthogonal multiple-access

- PA-MMSE:

-

Phase-aware minimum mean-squared error

- PN:

-

Phase noise

- PPP:

-

Poisson point process

- QoS:

-

Quality of service

- RIS:

-

Reconfigurable intelligent surface

- RSI:

-

Residual self-interference

- RF:

-

Radio frequency

- RMMSE:

-

Robust minimum mean-squared error

- RZF:

-

Regularized zero-forcing

- SC:

-

Small-cell

- SCA:

-

Successive convex approximation

- SE:

-

Spectral efficiency

- SIC:

-

Successive interference cancelation

- SINR:

-

Signal-to-interference-plus-noise ratio

- SLNR:

-

Signal-to-leakage-and-noise ratio

- SOCP:

-

Second-order cone program

- SNR:

-

Signal-to-noise ratio

- SWIPT:

-

Simultaneous wireless information and power transfer

- TDD:

-

Time-division duplex

- TR-LSFD:

-

Time-reversal large-scale fading decoding

- TR-MRC:

-

Time-reversal maximum-ratio combining

- TS:

-

Tabu search

- UE:

-

User equipment

- UI:

-

Multiuser interference

- UL:

-

Uplink

- WPT:

-

Wireless power transfer

- ZF:

-

Zero-forcing

References

Bhuvaneswari P, Nithyanandan L (2018) Improving energy efficiency in backhaul of LTE-A network with base station cooperation. Proc Comput Sci 143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2018.10.378

Saad W, Bennis M, Chen M (2019) A vision of 6G wireless systems: applications, trends, technologies, and open research problems. IEEE Netw. https://doi.org/10.1109/MNET.001.1900287

Ngo HQ, Ashikhmin A, Yang H, Larsson EG, Marzetta TL (2017) Cell-free massive MIMO versus small cells. IEEE Transact Wireless Commu 16(3):1834–1850. https://doi.org/10.1109/TWC.2017.2655515

Gangakhedkar S, Cao H, Ali AR, Ganesan K, Gharba M, Eichinger J (2018) Use cases, requirements and challenges of 5G communication for industrial automation. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCW.2018.8403588

Gandotra P, Jha RK (2017) A survey on green communication and security challenges in 5G wireless communication networks. J Network Comp Appl 96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnca.2017.07.002

Imoize AL, Adedeji O, Tandiya N, Shetty S (2021) 6G enabled smart infrastructure for sustainable society: opportunities, challenges, and research roadmap. Sensors 21(5):1709. https://doi.org/10.3390/s21051709

Bhat JR, AlQahtani SA (2021) 6G ecosystem: current status and future perspective. IEEE Access 10(6). https://doi.org/10.1109/access.2021.3054833

Rajatheva N et al (2020) White paper on broadband connectivity in 6G, pp 1–46

Chataut R, Akl R (2020) Massive MIMO systems for 5G and beyond networks—overview, recent trends, challenges, and future research direction. Sensors (Switzerland) 20(10). https://doi.org/10.3390/s20102753

Hoang TM, Ngo HQ, Duong TQ, Tuan HD, Marshall A (2018) Cell-free massive MIMO networks: optimal power control against active eavesdropping. IEEE Trans Commun 66(10):4724–4737. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCOMM.2018.2837132

Bjornson E, Sanguinetti L (2019) A new look at cell-free massive MIMO: making it practical with dynamic cooperation. https://doi.org/10.1109/PIMRC.2019.8904101

Demir ÖT, Björnson E, Sanguinetti L (2021) Foundations of user-centric cell-free massive MIMO. Found Trends Signal Process 14(3–4). https://doi.org/10.1561/2000000109

Akyildiz IF, Han C, Nie S (2018) Combating the distance problem in the millimeter wave and terahertz frequency bands. IEEE Commun Mag 56(6):102–108. https://doi.org/10.1109/MCOM.2018.1700928

Sun J, Chang H, Gao X, Wang CX, Huang J (2020) Multi-frequency multi-scenario millimeter wave MIMO channel measurements and modeling for B5G wireless communication systems. IEEE J Sel Areas Commun 38(9):2010–2025

MacCartney GR, Rappaport TS (2019) Millimeter-wave base station diversity for 5G coordinated multipoint (CoMP) applications. IEEE Trans Wirel Commun 18(7):3395–3410. https://doi.org/10.1109/TWC.2019.2913414

Akyildiz IF, Jornet JM, Han C (2014) Terahertz band: next frontier for wireless communications. Phys Commun 12:16–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phycom.2014.01.006

Petrov V, Pyattaev A, Moltchanov D, Koucheryavy Y (2016) Terahertz band communications: applications, research challenges, and standardization activities. Int Congr Ultra Mod Telecommun Control Syst Work 2016:183–190. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICUMT.2016.7765354

Chaccour C, Soorki MN, Saad W, Bennis M, Popovski P, Debbah M (2021) Seven defining features of terahertz (THz) wireless systems: a fellowship of communication and sensing. 1(4) Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/2102.07668

Nawaz SJ, Sharma SK, Wyne S, Patwary MN, Asaduzzaman M (2019) Quantum machine learning for 6G communication networks: state-of-the-art and vision for the future. IEEE Access 7(c):46317–46350. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2909490

Cacciapuoti AS, Caleffi M, Tafuri F, Cataliotti FS, Gherardini S, Bianchi G (2020) Quantum internet: networking challenges in distributed quantum computing. IEEE Netw 34(1):137–143. https://doi.org/10.1109/MNET.001.1900092

Wu Q, Zhang R (2020) Towards smart and reconfigurable environment: intelligent reflecting surface aided wireless network. IEEE Commun Mag 58(1):106–112. https://doi.org/10.1109/MCOM.001.1900107

Wu Q, Zhang R (2019) Intelligent reflecting surface enhanced wireless network via joint active and passive beamforming. IEEE Trans Wirel Commun 18(11):5394–5409. https://doi.org/10.1109/TWC.2019.2936025

Huang C, Zappone A, Alexandropoulos GC, Debbah M, Yuen C (2019) Reconfigurable intelligent surfaces for energy efficiency in wireless communication. IEEE Trans Wirel Commun 18(8):4157–4170. https://doi.org/10.1109/twc.2019.2922609

Tang W, Chen MZ, Chen X, Dai JY, Han Y, di Renzo M, Zeng Y, Jin S, Cheng Q, Cui TJ (2021) Wireless communications with reconfigurable intelligent surface: path loss modeling and experimental measurement. IEEE Trans Wirel Commun 20(1):421–439. https://doi.org/10.1109/TWC.2020.3024887

Ngo HQ, Ashikhmin A, Yang H, Larsson EG, Marzetta TL (2015) Cell-free massive MIMO: uniformly great service for everyone. https://doi.org/10.1109/SPAWC.2015.7227028

Interdonato G, Björnson E, Quoc Ngo H, Frenger P, Larsson EG (2019) Ubiquitous cell-free massive MIMO communications. EURASIP J Wirel Commun Netw 1(1):2019. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13638-019-1507-0

Buzzi S, D’andrea C, Zappone A, D’elia C (2020) User-centric 5G cellular networks: resource allocation and comparison with the cell-free massive MIMO approach. IEEE Trans Wirel Commun. https://doi.org/10.1109/TWC.2019.2952117

Ngo HQ, Tran LN, Duong TQ, Matthaiou M, Larsson EG (2017) Energy efficiency optimization for cell-free massive MIMO. https://doi.org/10.1109/SPAWC.2017.8227722

Zhu WP, Ajib W, Amarasuriya G, Kusaladharma S (2019) Achievable rate analysis of NOMA in cell-free massive MIMO: a stochastic geometry approach. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICC.2019.8761506

Lu L, Li GY, Swindlehurst AL, Ashikhmin A, Zhang R (2014) An overview of massive MIMO: benefits and challenges. IEEE J Selected Topics Signal Process 8(5):742–758. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSTSP.2014.2317671

Björnson E, Zakhour R, Gesbert D, Ottersten B (2010) Cooperative multicell precoding: rate region characterization and distributed strategies with instantaneous and statistical CSI. IEEE Trans Signal Process. https://doi.org/10.1109/TSP.2010.2049996

Nayebi E, Ashikhmin A, Marzetta TL, Yang H, Rao BD (2017) Precoding and power optimization in cell-free massive MIMO systems. IEEE Trans Wirel Commun. https://doi.org/10.1109/TWC.2017.2698449

Nayebi E, Ashikhmin A, Marzetta TL, Yang H (2016) Cell-free massive MIMO systems. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACSSC.2015.7421222

Boughaci D (2021) Solving optimization problems in the fifth generation of cellular networks by using meta-heuristics approaches. Proc Comput Sci 182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2021.02.008

Hamdi R, Driouch E, Ajib W (2017) Energy management in hybrid energy large-scale MIMO systems. IEEE Trans Veh Technol 66(11). https://doi.org/10.1109/TVT.2017.2757401

Alamu O, Gbenga-Ilori A, Adelabu M, Imoize A, Ladipo O (2020) Energy efficiency techniques in ultra-dense wireless heterogeneous networks: an overview and outlook. Eng Sci Technol an Int J 23(6):1308–1326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jestch.2020.05.001

Hamdi R, Qaraqe M (2020) Power allocation and cooperation in cell-free massive MIMO systems with energy exchange capabilities. https://doi.org/10.1109/VTC2020-Spring48590.2020.9129410

Piovesan N, Fernandez Gambin A, Miozzo M, Rossi M, Dini P (2018) Energy sustainable paradigms and methods for future mobile networks: a survey. Comput Commun 119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comcom.2018.01.005

Mahapatra R, Nijsure Y, Kaddoum G, Ul Hassan N, Yuen C (2016) Energy efficiency tradeoff mechanism towards wireless green communication: a survey. IEEE Commun Surv Tutorials 18(1):686–705. https://doi.org/10.1109/COMST.2015.2490540

Zuo J, Zhang J, Yuen C, Jiang W, Luo W (2016) Energy efficient downlink transmission schemes for multi-cell massive distributed antenna systems. IEEE Vehicular Technol Conf 2016. https://doi.org/10.1109/VTCSpring.2016.7504221

Hamdi R, Qaraqe M (2019) Energy cooperation in renewable- powered cell-free massive MIMO systems. https://doi.org/10.1109/APCC47188.2019.9026523

Le QN, Nguyen VD, Dobre OA, Zhao R (2021) Energy efficiency maximization in RIS-aided cell-free network with limited backhaul. IEEE Commun Lett. https://doi.org/10.1109/LCOMM.2021.3062275

Li S, Duo B, Yuan X, Liang Y-C, Di Renzo M (2020) Reconfigurable intelligent surface assisted UAV communication: joint trajectory design and passive beamforming. IEEE Wirel Commun Lett 2337(c):1–720. https://doi.org/10.1109/lwc.2020.2966705

Amarasuriya G, Larsson EG, Poor HV (2016) Wireless information and power transfer in multiway massive MIMO relay networks. IEEE Trans Wirel Commun 15(6). https://doi.org/10.1109/TWC.2016.2530067

Varshney LR (2008) Transporting information and energy simultaneously. https://doi.org/10.1109/ISIT.2008.4595260

Ding Z et al (2015) Application of smart antenna technologies in simultaneous wireless information and power transfer. IEEE Commun. Mag 53(4). https://doi.org/10.1109/MCOM.2015.7081080

Xia X, Zhang D, Xu K, Ma W, Xu Y (2015) Hardware impairments aware transceiver for full-duplex massive MIMO relaying. IEEE Trans Signal Process. 63(24). https://doi.org/10.1109/TSP.2015.2469635

Zhang J, Wei Y, Bjornson E, Han Y, Jin S (2018) Performance analysis and power control of cell-free massive MIMO systems with hardware impairments. IEEE Access. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2018.2872715

Zhang Y, Cao H, Zhou M, Li L, Yang L (2020) Power optimization in cell-free massive MIMO with non-ideal hardware transceiver. Chin J Electron 29(1). https://doi.org/10.1049/cje.2019.12.005

Zhang J, Dai L, He Z, Jin S, Li X (2017) Performance analysis of mixed-ADC massive MIMO systems over rician fading channels. IEEE J Sel Areas Commun 35(6). https://doi.org/10.1109/JSAC.2017.2687278

Zhang J, Dai L, Sun S, Wang Z (2016) On the spectral efficiency of massive MIMO systems with low-resolution ADCs. IEEE Commun Lett 20(5). https://doi.org/10.1109/LCOMM.2016.2535132

Alonzo M, Buzzi S, Zappone A, D’Elia C (2019) Energy-efficient power control in cell-free and user-centric massive MIMO at millimeter wave. https://doi.org/10.1109/TGCN.2019.2908228

Mai TC, Ngo HQ, Egan M, Duong TQ (2018) Pilot power control for cell-free massive MIMO. IEEE Trans Veh Technol. https://doi.org/10.1109/TVT.2018.2867606

Chen Z, Bjornson E (2018) Channel hardening and favorable propagation in cell-free massive MIMO with stochastic geometry. IEEE Trans Commun. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCOMM.2018.2846272

Mai TC, Quoc Ngo H, Duong TQ (2019) Cell-free massive MIMO systems with multi-antenna users. https://doi.org/10.1109/GlobalSIP.2018.8646330

Gkonis PK, Trakadas PT, Kaklamani DI (2020) A comprehensive study on simulation techniques for 5G networks: state of the art results, analysis, and future challenges. Electronics (Switzerland) 9(3). https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics9030468

Memon ML, Maheshwari MK, Saxena N, Roy A, Shin DR (2019) Artificial intelligence-based discontinuous reception for energy saving in 5G networks. Electron. 8(7). https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics8070778

Alkhateeb A, Alex S, Varkey P, Li Y, Qu Q, Tujkovic D (2018) Deep learning coordinated beamforming for highly-mobile millimeter wave systems. IEEE Access 6. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2018.2850226

Lee W, Kim M, Cho DH (2018) Deep power control: transmit power control scheme based on convolutional neural network. IEEE Commun Lett 22(6). https://doi.org/10.1109/LCOMM.2018.2825444

Luo C, Ji J, Wang Q, Yu L, Li P (2018) Online power control for 5G wireless communications: a deep q-network approach. IEEE Int Conf Commun 2018. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICC.2018.8422442

Zhou P, Fang X, Wang X, Long Y, He R, Han X (2019) Deep learning-based beam management and interference coordination in dense mmWave networks. IEEE Trans Veh Technol 68(1). https://doi.org/10.1109/TVT.2018.2882635

Chen Z, Bjoernson E (2018) Can We Rely on Channel Hardening in Cell-Free Massive MIMO? https://doi.org/10.1109/GLOCOMW.2017.8269162

Ojo S, Imoize A, Alienyi D (2021) Radial basis function neural network path loss prediction model for LTE networks in multitransmitter signal propagation environments. Int J Commun Syst 34(e4680):1–26. https://doi.org/10.1002/dac.4680

Polegre AA, Riera-Palou F, Femenias G, Armada AG (2020) New insights on channel hardening in cell-free massive MIMO networks. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCWorkshops49005.2020.9145215

Tu LT, Di Renzo M (2017) Analysis of millimeter wave cellular networks with simultaneous wireless information and power transfer. https://doi.org/10.1109/SIGTELCOM.2017.7849792

Liao Y, Zhang J, Zhang Y, Chen M, Li Q, Han T (2016) Performance analysis of K-tier cellular networks with time-switching energy harvesting. https://doi.org/10.1109/PIMRC.2016.7794611

Di Renzo M, Lu W (2017) System-level analysis and optimization of cellular networks with simultaneous wireless information and power transfer: stochastic geometry modeling. IEEE Trans Veh Technol. https://doi.org/10.1109/TVT.2016.2574811

Shrestha R, Amarasuriya G (2018) SWIPT in cell-free massive MIMO. https://doi.org/10.1109/GLOCOM.2018.8648129

Kusaladharma S, Zhu WP, Ajib W, Amarasuriya G (2020) Performance of SWIPT in cell-free massive MIMO: a stochastic geometry based perspective. https://doi.org/10.1109/CCNC46108.2020.9045726

Liu A, Lau VKN (2017) Joint BS-user association, power allocation, and user-side interference cancellation in cell-free heterogeneous networks. IEEE Trans Signal Process. https://doi.org/10.1109/TSP.2016.2620962

Interdonato G, Frenger P, Larsson EG (2019) Scalability aspects of cell-free massive MIMO. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICC.2019.8761828

Li T, Sahu AK, Talwalkar A, Smith V (2020) Federated learning: challenges, methods, and future directions. IEEE Signal Process Mag. https://doi.org/10.1109/MSP.2020.2975749

Brendan McMahan H, Moore E, Ramage D, Hampson S, Agüera y Arcas B (2017) Communication-efficient learning of deep networks from decentralized data

Tran NH, Bao W, Zomaya A, Nguyen MNH, Hong CS (2019) Federated learning over wireless networks: optimization model design and analysis. https://doi.org/10.1109/INFOCOM.2019.8737464

Wang S, Tuor T, Salonidis T, Leung KK, Makaya C, He T, Chan K (2019) Adaptive federated learning in resource constrained edge computing systems. IEEE J Sel Areas Commun 37(6):1205–1221. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSAC.2019.2904348

Yang K, Jiang T, Shi Y, Ding Z (2020) Federated learning via over-the-air computation. IEEE Trans Wirel Commun. https://doi.org/10.1109/TWC.2019.2961673

Zhang X, Guo D, An K, Zhang B (2020) Secure communications over cell-free massive MIMO networks with hardware impairments. IEEE Syst J. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSYST.2019.2919584

Yang H, Marzetta TL (2018) Energy efficiency of massive MIMO: cell-free vs. cellular. https://doi.org/10.1109/VTCSpring.2018.8417645

Bashar M, Cumanan K, Burr AG, Ngo HQ, Debbah M, Xiao P (2019) Max-min rate of cell-free massive MIMO uplink with optimal uniform quantization. IEEE Trans Commun 67(10). https://doi.org/10.1109/TCOMM.2019.2926706

Mai TC, Ngo HQ, Duong TQ (2019) Uplink spectral efficiency of cell-free massive MIMO with multi-antenna users. https://doi.org/10.1109/SIGTELCOM.2019.8696221

D’Andrea C, Zappone A, Buzzi S, Debbah M (2019) Uplink power control in cell-free massive MIMO via deep learning. https://doi.org/10.1109/CAMSAP45676.2019.9022520

Ajani TS, Imoize AL, Atayero AA (2020) An overview of machine learning within embedded and mobile devices – optimizations and applications, pp 1–44

Ngo HQ, Tran LN, Duong TQ, Matthaiou M, Larsson EG (2018) On the total energy efficiency of cell-free massive MIMO. https://doi.org/10.1109/TGCN.2017.2770215

Zhang Y, Zhou M, Cheng Y, Yang L, Zhu H (2020) RF impairments and low-resolution ADCs for nonideal uplink cell-free massive MIMO systems. IEEE Syst J. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSYST.2020.2990709

Fan W, Zhang J, Bjornson E, Chen S, Zhong Z (2019) Performance analysis of cell-free massive MIMO over spatially correlated fading channels. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICC.2019.8762051

Interdonato G, Ngo HQ, Larsson EG, Frenger P (2016) On the performance of cell-free massive MIMO with short-term power constraints. https://doi.org/10.1109/CAMAD.2016.7790362

Li Y, Aruma Baduge GA (2018) NOMA-aided cell-free massive MIMO systems. IEEE Wirel Commun Lett. https://doi.org/10.1109/LWC.2018.2841375

Bashar M, Cumanan K, Burr AG, Ngo HQ, Larsson EG, Xiao P (2019) On the energy efficiency of limited-backhaul cell-free massive MIMO. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICC.2019.8761134

Imoize AL, Ibhaze AE, Atayero AA, Kavitha KVN (2021) Standard propagation channel models for MIMO communication systems. Wirel Commun Mob Comput 2021(8838792):36. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/8838792

Ogbebor JO, Imoize AL, Atayero AA-A (2020) Energy efficient design techniques in next-generation wireless communication networks: emerging trends and future directions. Wirel Commun Mob Comput 2020(7235362):19. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/7235362

Marzetta TL, Larsson EG, Yang H, Ngo HQ (2016) Fundamentals of massive MIMO. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781316799895

Björnson E, Hoydis J, Sanguinetti L (2017) Massive MIMO networks: spectral, energy, and hardware efficiency. Foundations Trends in Signal Process 11(3–4) Now Publishers Inc:154–655. https://doi.org/10.1561/2000000093

Larsson EG, Edfors O, Tufvesson F, Marzetta TL (2014) Massive MIMO for next generation wireless systems. IEEE Commun Mag 52(2):186–195. https://doi.org/10.1109/MCOM.2014.6736761

Marzetta TL (2010) Noncooperative cellular wireless with unlimited numbers of base station antennas. IEEE Trans Wirel Commun. https://doi.org/10.1109/TWC.2010.092810.091092

Ngo HQ, Larsson EG, Marzetta TL (2013) Energy and spectral efficiency of very large multiuser MIMO systems. IEEE Trans Commun 61(4):1436–1449. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCOMM.2013.020413.110848

Rusek F, Persson D, Buon Kiong Lau, Larsson EG, Marzetta TL, Tufvesson F (2013) Scaling up MIMO : opportunities and challenges with very large arrays. IEEE Signal Process Mag 30(1):40–60. https://doi.org/10.1109/MSP.2011.2178495

Truong KT, Heath RW (2013) The viability of distributed antennas for massive MIMO systems. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACSSC.2013.6810508

Venkatesan S, Lozano A, Valenzuela R (2007) Network MIMO: overcoming intercell interference in indoor wireless systems. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACSSC.2007.4487170

Gesbert D, Hanly S, Huang H, Shamai Shitz S, Simeone O, Yu W (2010) Multi-cell MIMO cooperative networks: a new look at interference. IEEE J Sel Areas Commun. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSAC.2010.101202

Zhang J, Dai L, Li X, Liu Y, Hanzo L (2018) On low-resolution ADCs in practical 5G millimeter-wave massive MIMO systems. IEEE Commun Mag 56(7). https://doi.org/10.1109/MCOM.2018.1600731

Björnson E, Larsson EG, Debbah M (2016) Massive MIMO for maximal spectral efficiency: how many users and pilots should be allocated? https://doi.org/10.1109/TWC.2015.2488634

Yang H, Marzetta TL (2013) Total energy efficiency of cellular large scale antenna system multiple access mobile networks. https://doi.org/10.1109/OnlineGreenCom.2013.6731024

Zhang J, Chen S, Lin Y, Zheng J, Ai B, Hanzo L (2019) Cell-free massive MIMO: a new next-generation paradigm. IEEE Access. https://doi.org/10.1109/access.2019.2930208

Bjornson E, Sanguinetti L (2020) Making cell-free massive MIMO competitive with MMSE processing and centralized implementation. IEEE Trans Wirel Commun. https://doi.org/10.1109/TWC.2019.2941478

Dai L, Wang B, Ding Z, Wang Z, Chen S, Hanzo L (2018) A survey of non-orthogonal multiple access for 5G. IEEE Commun Surv Tutorials 20(3):2294–2323. https://doi.org/10.1109/COMST.2018.2835558

Yang K, Yang N, Ye N, Jia M, Gao Z, Fan R (2019) Non-orthogonal multiple access: achieving sustainable future radio access. IEEE Commun Mag. https://doi.org/10.1109/MCOM.2018.1800179

An J, Yang K, Wu J, Ye N, Guo S, Liao Z (2017) Achieving sustainable ultra-dense heterogeneous networks for 5G. IEEE Commun Mag 55(12). https://doi.org/10.1109/MCOM.2017.1700410

Zhang Z, Sun H, Hu RQ, Qian Y (2016) Stochastic geometry based performance study on 5G non-orthogonal multiple access scheme. https://doi.org/10.1109/GLOCOM.2016.7842300

Saito Y, Kishiyama Y, Benjebbour A, Nakamura T, Li A, Higuchi K (2013) Non-orthogonal multiple access (NOMA) for cellular future radio access. https://doi.org/10.1109/VTCSpring.2013.6692652

Sun Q, Han S, Chin-Lin I, Pan Z (2015) On the ergodic capacity of MIMO NOMA systems. IEEE Wirel Commun Lett 4(4). https://doi.org/10.1109/LWC.2015.2426709

Burr A, Bashar M, Maryopi D (2018) Ultra-dense radio access networks for smart cities: cloud-RAN, fog-RAN and ‘cell-free’ massive MIMO. arXiv

Gustavsson U et al (2014) On the impact of hardware impairments on massive MIMO. https://doi.org/10.1109/GLOCOMW.2014.7063447

Bacha MN, Evans JS, Hanly SV (2006) On the capacity of MIMO cellular networks with macrodiversity. https://doi.org/10.1109/ausctw.2006.1625264

Xiang Z, Tao M, Wang X (2014) Massive MIMO multicasting in noncooperative cellular networks. IEEE J Sel Areas Commun. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSAC.2014.2328144

Ngo HQ, Larsson EG, Marzetta TL (2014) Aspects of favorable propagation in massive MIMO. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.43970

Liu P, Luo K, Chen D, Jiang T (2020) Spectral efficiency analysis of cell-free massive MIMO systems with zero-forcing detector. IEEE Trans Wirel Commun. https://doi.org/10.1109/TWC.2019.2948841

Huh H, Caire G, Papadopoulos HC, Ramprashad SA (2012) Achieving ‘massive MIMO’ spectral efficiency with a not-so-large number of antennas. IEEE Trans Wirel Commun. https://doi.org/10.1109/TWC.2012.070912.111383

Imoize AL, Orolu K, Atayero AA-A (2020) Analysis of key performance indicators of a 4G LTE network based on experimental data obtained from a densely populated smart city. Data Br 29(105304):1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dib.2020.105304

Shuaifei Chen BA, Zhang J, Zhang J, Björnson E (2021) A survey on user-centric cell-free massive MIMO systems

Kumar S, Chandrasekaran G, Kalyani S (2015) Analysis of outage probability and capacity for κ-μ/η-μ faded channel. IEEE Commun Lett 19(2). https://doi.org/10.1109/LCOMM.2014.2371051

Beiranvand J, Meghdadi H (2018) Analytical performance evaluation of MRC receivers in massive MIMO systems. IEEE Access 6. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2018.2866795

Atapattu S, Dharmawansa P, Tellambura C, Evans J (2017) Exact outage analysis of multiple-user downlink with MIMO matched-filter precoding. IEEE Commun Lett 21(12). https://doi.org/10.1109/LCOMM.2017.2749302

Interdonato G, Ngo HQ, Larsson EG, Frenger P (2016) How much do downlink pilots improve cell-free massive MIMO? https://doi.org/10.1109/GLOCOM.2016.7841875

Elhoushy S, Hamouda W (2020) Performance of distributed massive MIMO and small-cell systems under hardware and channel impairments. IEEE Trans Veh Technol. https://doi.org/10.1109/TVT.2020.2998405

Francis J, Baracca P, Wesemann S, Fettweis G (2019) Downlink power control in cell-free massive MIMO with partially distributed access points. https://doi.org/10.1109/VTCFall.2019.8891216

Vu TT, Ngo DT, Tran NH, Ngo HQ, Dao MN, Middleton RH (2020) Cell-free massive MIMO for wireless federated learning. IEEE Trans Wirel Commun. https://doi.org/10.1109/TWC.2020.3002988

Vu TT, Ngo DT, Ngo HQ, Le-Ngoc T (2019) Full-duplex cell-free massive MIMO. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICC.2019.8761711

Rezaei F, Tellambura C, Tadaion AA, Heidarpour AR (2020) Rate analysis of cell-free massive MIMO-NOMA with three linear precoders. IEEE Trans Commun. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCOMM.2020.2978189

Nguyen TK, Nguyen HH, Tuan HD (2020) Max-min QoS power control in generalized cell-free massive MIMO-NOMA with optimal backhaul combining. IEEE Trans Veh Technol. https://doi.org/10.1109/TVT.2020.3006054

Galappaththige DL, Amarasuriya G (2020) NOMA-aided cell-free massive MIMO with underlay spectrum-sharing. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICC40277.2020.9149105

Bashar M et al (2020) Uplink spectral and energy efficiency of cell-free massive MIMO with optimal uniform quantization. IEEE Trans Commun. https://doi.org/10.1109/tcomm.2020.3028305

Van Chien T, Bjornson E, Larsson EG (2020) Optimal design of energy-efficient cell-free massive MIMO: joint power allocation and load balancing. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICASSP40776.2020.9054083

Interdonato G, Ngo HQ, Larsson EG (2021) Enhanced normalized conjugate beamforming for cell-free massive MIMO. IEEE Trans Commun. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCOMM.2021.3055522

Masoumi H, Emadi MJ (2020) Performance analysis of cell-free massive MIMO system with limited fronthaul capacity and hardware impairments. IEEE Trans Wirel Commun. https://doi.org/10.1109/TWC.2019.2950316

Zheng J, Zhang J, Zhang L, Zhang X, Ai B (2020) Efficient receiver design for uplink cell-free massive MIMO with hardware impairments. IEEE Trans Veh Technol. https://doi.org/10.1109/TVT.2020.2975354

Verenzuela D, Bjornson E, Matthaiou M (2021) Optimal per-antenna ADC bit allocation in correlated and cell-free massive MIMO. IEEE Trans Commun. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCOMM.2021.3067699

Zhang J, Wei Y, Bjornson E, Han Y, Li X (2017) Spectral and energy efficiency of cell-free massive MIMO systems with hardware impairments. In: 2017 9th International Conference on Wireless Communications and Signal Processing, WCSP 2017 - Proceedings, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1109/WCSP.2017.8171057

Chakraborty S, Bjornson E, Sanguinetti L (2019) Centralized and distributed power allocation for max-min fairness in cell-free massive MIMO. https://doi.org/10.1109/IEEECONF44664.2019.9048903

Nuwanthika Rajapaksha ML, Shashika Manosha KB, Rajatheva N (2021) Deep learning-based power control for cell-free massive MIMO networks. Cent Wirel Commun Univ Oulu Finl