Abstract

Background

Low back pain (LBP) is a highly prevalent musculoskeletal condition and causes activity limitations resulting in reduced productivity and high medical expenditure. Muscle energy technique (MET) is a therapeutic technique that has the potential to be successful in LBP, although the evidence for this notion is still inconclusive. The effectiveness of the muscular energy technique on pain intensity and disability for individuals with chronic low back pain was evaluated in published studies through this systematic review of the literature.

Methods

Studying the English language and humans, as well as scanning article reference lists from PubMed, Scopus, ScienceDirect, the Cochrane Library, Ovid, ClinicalTrials.gov, and Embase, was searched until October 30, 2022. Randomised controlled studies reporting on the effectiveness of muscle energy technique on pain intensity and disability for chronic low back patients were included. Information related to demographics, number and duration of treatment, MET protocol, assessment tools used for pain and disability, and key findings was extracted. The Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro) classification scale was used to assess the methodological quality of studies, and two authors assessed the risk of bias and extracted the data independently.

Results

Seventeen research studies (including 817 participants) were retrieved and included for qualitative analysis. The studies published between 2011 and 2022 were retrieved, and the sample size ranged from 10 to one hundred twenty-five participants. The age of the subjects ranged between 18 and 60 years, and interventions were done between 2 days and 12 weeks. Of the included 17 studies, five were from Egypt, four were from India, two each from Iran and Nigeria, and one each from Brazil, Poland, Thailand, and Pakistan. Compared to other interventions or the control groups, MET was found to significantly, although modestly, decrease the severity of pain and reduce functional disability in patients with chronic LBP. Most of the included studies had moderate to high study quality.

Conclusion

In patients with chronic low back pain (CLBP), it was observed that MET alone as well as in conjunction with other interventions was found to be beneficial in reducing pain intensity, improving lumbar spine range of motion, and decreasing the degree of functional disability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Among all musculoskeletal disorders, low back pain (LBP) is the most prevalent type affecting people of all ages, significantly adding to socioeconomic burden. Seventy to 85% of people at some point in their life will experience LBP, according to published statistical data [1]. After an acute episode of pain, only 39–76% of patients fully recover, suggesting that a sizeable portion of them go on to acquire a chronic condition [2,3,4]. The condition has been ranked 6th out of 291 diseases by the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) because it is associated with a significant disease burden. This has a negative impact on activity levels, lowers productivity at work, and resulting in healthcare costs that exceed billions of dollars yearly [5].

The reasons of LBP are numerous, ranging from visceral factors to inadequate blood supply to the muscles or musculoskeletal imbalance [6, 7]. The proper therapy of chronic low back pain (CLBP) is essential given its substantial economic and social consequences. Currently, managing LBP is difficult due to its complexity, high expense, and unexpected results [8]. Single-model LBP interventions have shown little to no benefit [9]. The muscle energy technique (MET), created by Fred Mitchell, is a popular conservative treatment for pathologies of the spine, primarily in LBP and disability [2]. This therapeutic approach is significant in physical therapy. MET is one of the most widely used treatment techniques for increasing elasticity in both contractile and non-contractile tissues [1, 3]. According to studies, MET is as effective as manipulation for treating low back pain. Compared to passive and static stretching, MET more efficiently increases muscular extensibility. The cervical spine, lumbar spine, and spinal joints in general have been proven to benefit from MET [2]. Various protocols have been developed with varied specifics for each step, including duration and strength of contraction, duration of rest, and the number of repetitions. MET protocols developed differ in paradigms, such as in the digit of repetitions, the strength of contraction, duration of the stretch phase, and duration of the relaxation phase. Two of the most prominent MET typologies of application are those advocated by Greenman and Chaitow.

The continuous search for new effective treatment modalities is spurred by the high frequency of chronic spinal disorders, inconsistent diagnostic and therapeutic procedures, and significant financial burden associated with their management. Understanding neurophysiological processes, correctly interpreting pain, spotting undesirable motor and postural patterns, treating the patient holistically, and fusing the knowledge with diverse treatment approaches are all necessary for this. A systematic review is a scientific inquiry that uses pre-planned methods and a collection of original studies as its focus. The review combines the results of multiple primary studies by implementing techniques that minimise bias and chance variations. These reviews can help to clarify differences in approaches or to validate the effectiveness of current methods. Despite the fact that multiple studies have already been published that addressed a variety of LBP treatment options, the evidence for effectiveness of those treatments is still quite inadequate. Therefore, the goal of this systematic review of RCTs was to determine how well the muscle energy technique works for chronic low back pain patients in terms of pain intensity and disability.

Materials and methods

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist guidelines were followed [10].

Search strategy

Using seven separate databases (PubMed, Embase, the Cochrane Library, Scopus, ScienceDirect, ClinicalTrials.gov, and Ovid), a thorough literature search was conducted in relevant peer-reviewed journals published from 2011 to 2022.

After deduplication, titles were screened, and potentially relevant articles were identified by analysing associated abstracts. Study information was abstracted from full texts of articles included in the study. Through manual searches of cited references for related papers retrieved, further publications were identified (snowball referencing).

The above searches used the PICO (P, patient or problems; I, intervention; C, comparison of interventions; O, outcome measurement) strategy.

-

P: Subjects (age = 18–70 years) with CLBP more than 3 months

-

I: Muscle energy technique

-

C: Other intervention techniques or control

-

O: Pain and functional disability

For database searches, the broad key terms used were muscles energy technique AND chronic low back pain OR CLBP, and only research articles were retrieved and reviewed by two independent reviewers.

Inclusion criteria

-

(1)

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) investigating the effectiveness of MET in patients with subacute or chronic non-specific low back pain

-

(2)

Articles published in English language

-

(3)

Research carried out in the period of 2011–2022

-

(4)

Original publications with adequate detail to determine the critical information of the research studies

-

(5)

Subjects 18–70 years old (male or female) with CLBP more than 3 months

Exclusion criteria

-

(1)

Studies published in languages other than English

-

(2)

Studies in subjects < 18 years of age and CLBP less than 3 months

-

(3)

Studies whose outcomes did not involve intensity of low back pain

-

(4)

Studies without results or not providing sufficient data

-

(5)

Protocols, guidelines, editorials, book chapters, letter to editor, reviews, and meta-analysis

-

(6)

Animal studies

-

(7)

Study designs other than RCTs

-

(8)

Patients with previous back surgery, lumbar disc herniation, spinal deformities, neuro-musculoskeletal problems, rheumatoid arthritis, and patients with osteoporosis

-

(9)

Poster presentation of studies were excluded.

Data extraction and synthesis

A typical Excel spreadsheet was used to extract the data. Table 1 provides an overview of the salient features of the included studies. Authors, publication year, sample size, age, gender, participants, number of treatments and duration of treatment, MET protocol, assessment tool for pain and functional disability, and key findings were abstracted for each included study. The researchers were contacted to obtain data whenever required.

Study quality assessment

The quality of selected studies was assessed using the PEDro classification scale [25]. Using the PEDro classification scale, two researchers independently assessed the methodological quality of each included study. Disagreements between the two reviewers were resolved by discussion and consensus.

The PEDro classification scale is a reliable indicator of the methodological quality of clinical trials [25]. Its 10-item scores are added up to provide a total score that ranges from 0 to 10. Each included study’s methodological quality was assessed as high (≥ 7/10), medium (4–6/10), or low (≤ 3/10) based on the PEDro score.

Results

Identification and description of included studies

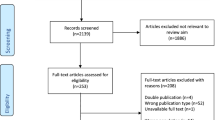

There were 4514 citations in all, of which 93 were from PubMed, 157 were from Embase, 19 were from the Cochrane Library, 79 were from Ovid, 3944 from Scopus, 5 from ClinicalTrials.gov, and 217 were from ScienceDirect. Of these, 346 duplicate cases were excluded. After screening the titles and abstracts of 4168 studies, 3726 records were eliminated. The final 442 articles met the requirements for full-text review. Out of 442 full texts, 425 were eliminated after applying the exclusion criteria, and 17 articles were included for the final qualitative analysis. The flow diagram shows the search strategy (Fig. 1).

Characteristics of the included studies

Seventeen RCTs were identified up to October 2022 that were published between 2011 and 2022. The studies included 817 participants in total, with sample size ranging from 10 to 125. Out of the 17 studies that were included, the age of the subjects ranged between 18 and 60 years, and interventions were done between 2 days to 12 weeks. Table 1 summarises the key demographic and clinical characteristics of each included study. Of the included 17 studies published from eight countries, five were from Egypt; four were from India; two each from Iran, and Nigeria; and one each from Brazil, Poland, Thailand, and Pakistan.

Effectiveness of MET on pain intensity and disability for chronic low back patients

All the 17 studies reported the following: the effectiveness of MET in reducing the pain intensity level, improvement in lumbar spine ROM, and reduction in function disability level. These studies evaluated the effectiveness of MET with various different interventions, and several research included more than one comparison group. When associated to or compared with MET, the activities that the various groups carried out were as follows: cranial sacral therapy (CST); McKenzie extension exercise programme (MEE); sensory motor training (SMT); high velocity and low amplitude technique (HLVA); strain-counter strain technique (SCS); dynamic stabilisation exercise (DSE); lumbar stabilisation exercise (LSE); conventional physiotherapy intervention; core stability exercise (SE); proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation (FNP); static stretching in hamstring flexibility (SS); transcutaneous electrical stimulation (TENS); therapeutic ultrasound (US); therapeutic exercise programme (USPT); myofascial release (MRF); Pilate mat exercise (PME); Kinesio Taping; and stretching and strengthening exercises (SSE). The Oswestry Impairment Index (ODI), the Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ), and the Modified Oswestry Disability Questionnaire (MODQ) were used to evaluate functional disability. Scales such the VAS (Visual Analog Scale), NPS (Neuropathic Pain Scale), NRS (Numerical Rating Scale), SF-MPQ (Short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire), QBPDS (Quebec back pain disability scale), MPI (Multidimensional Pain Inventory), and OMPSQ (Örebro Musculoskeletal Pain Questionnaire) were used to assess the intensity of LBP.

Ahmed et al. [1] examined the impact of a combination of DSE and MET on specific biopsychosocial outcomes in the treatment of CLBP in comparison to DSE alone or traditional physiotherapy. Patients were divided into three groups: DSE Plus MET (n = 41), DSE alone (n = 39), or traditional physiotherapy (n = 45) using a random number generator approach. Over the course of 12 weeks, interventions were given twice a week. The research outcomes demonstrated within-group improvements in all intervention groups over time (p < 0.001). MET with DSE led to greater improvements in pain intensity, lumbar ROM, activity limitations/participation restrictions, and health status. For all outcome measures, the MET plus DSE therapies outperformed DSE and traditional physiotherapy, with the exception of functional impairment (p = 0.590). It was observed that using MET and DSE together is safe and effective in treating individuals with chronic NSLBP.

In a study of 69 individuals with CLBP, Akodu et al. [15] compared the effects of MET and CSE on pain, disability, and range of motion. Using computer-generated numbers, subjects were divided into four separate groups at random. Group 4 acted as the control and got stretching exercises and back care guidance, while groups 1 and 2 received MET, CSE, MET, and CSE, and group 3 received only CSE. According to studies, the four groups’ clinical outcomes—pain, functional impairment, and lumbar range of motion—improved post-intervention (p < 0.05). The MET and CSE group combined to generate better clinical results in terms of pain, functional impairment, and range of motion.

Ellythy [13] evaluated how well manual therapy modalities affected individuals with CLBP in terms of outcome metrics. To create two equivalent therapy groups, 40 patients with persistent low back pain were randomly allocated. The first group (group A) undertook a 4-week programme of targeted physical therapy together with post-isometric relaxation (PIR) to address their muscular energy. The second group (group B) went through a 4-week myofascial release treatment in addition to a targeted physical therapy programme. The results of this experiment provide credence to the idea that integrating certain manipulation methods into patients’ daily activities might significantly lessen their pain and functional impairment. Additionally, Ellythy [14] compared the effects of SCS method and MET on outcome metrics in individuals with persistent low back pain. The two equal treatment groups for the thirty chronic low back pain patients were chosen at random. A 4-week regimen of muscular energy therapy was administered to the first group (n = 15). The second group (n = 15) completed a strain-counter strain therapy regimen for 4 weeks. The findings demonstrated that individuals with persistent low back pain can reduce pain and functional impairment using both MET and SCS approaches.

Tubassam and colleagues [23] performed a quasi-experimental trial on 40 participants who reported trigger point-related low back pain. There were two groups of participants: group A (MET) and group B (SCS). For 2 weeks, group B received treatment with strain-counter strain method and moist heat therapy, whereas group A received treatment with muscular energy techniques and moist heat therapy. CLBP patients spurred on by trigger points in the quadratus lumborum experienced considerable pain relief and decreased functional impairment after undergoing METS or SCS. The posttreatment NPRS scores for group A (MET) and group B (SCS) were 3.20 ± 1.16 vs. 4.55 ± 1.20, respectively.

In patients with CLBP, Gendy et al. [24] highlighted the advantages of PME and MET on pain intensity, functional impairment, trunk range of motion, and flexibility. After therapy, the ROM, VAS, VSR, and Ronald score all showed varying degrees of improvement as well as statistically significant variations with big size effects. Chronic non-specific low back pain can be effectively treated using a variety of therapeutic techniques; however, the Pilate mat exercise approach produced superior outcomes.

In 60 participants with LBP, Szulc and colleagues [3] evaluated the effectiveness of a combined McKenzie technique and muscle energy technique (MET) therapy. The McKenzie technique with MET, the McKenzie method alone, or 10 days of routine physiotherapy were given to the patients at random. The highest treatment results came from the McKenzie approach enhanced with MET. The cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spine’s mobility returned to normal. Implementing the McKenzie approach led to a considerable decline in the Oswestry Disability Index, a significant reduction in pain (VAS), and a significant reduction in the extent of the spinal disc herniation, both when used alone and in conjunction with MET.

When managing low back pain caused by SI joint dysfunction, Dhinkaran and colleagues [11] compared MET and traditional physiotherapy. The subjects were allocated into two groups at random: group A (n = 15), which received MET and remedial exercises, and group B (n = 15) (TENS and corrective exercises were given). The study findings demonstrated that MET is relatively significant compared to traditional physiotherapy, such as TENS with corrective exercises, in increasing functional capacity and reducing discomfort. Bindra et al. examined the relative efficacy of MET and traditional therapy for treating CLBP brought on by sacroiliac joint dysfunction (SIJD) [12]. In the MET group, the SIJD-related apparent functional leg length difference could be nearly normalised. Both groups had nearly identical outcomes in terms of the decrease of pain and impairment.

Bhosale and Burungale [22] evaluated the combined effects of myofascial release therapy, the muscular energy technique, and stretching of the quadratus lumborum muscle in CLBP patients. Two groups were split into an experimental group and a control group for this investigation. Patients with CLBP have found that a combination of myofascial release, MET, and quadratus lumborum stretching is useful in treating their condition.

Sturion et al. [21] evaluated the effects of two osteopathic manipulative treatments on trunk neuromuscular postural control and clinical low back complaints in male employees with CLBP. Ten male candidates with CLBP were divided into two groups at random: HVLA or MET. Large clinical differences were seen between the immediate and 15-day pain reduction effects of both strategies (p < 0.01). The neuromuscular activity and postural balance tests, which are additional factors, did not show any differences between groups or times.

The impact of muscular energy method and neural tissue mobilisation on hamstring tightness in CLBP was reported by Patel et al. [20]. Fifty-two patients with CLBP and hamstring tightness participated in this comparative investigation. According to the study, both muscle energy method and neural tissue mobilisation relieve hamstring tightness in persistent low back pain. Fahmy et al. [17] studied 40 patients with persistent mechanical low back pain to assess the effectiveness of an extension exercise programme vs MES. Patients were allocated into two equal groups by random selection: group A underwent a spinal extension exercise programme, whereas group B received MES. Both groups’ posttreatment pain and functional impairment scores significantly decreased, although group B’s improvement was more pronounced. Both groups’ lumbar range of motion significantly increased after therapy, although group A’s improvement was more pronounced.

Elshinnawy et al. [16] looked at how MET and Kinesio Taping affected individuals with chronic low back dysfunction in terms of pain intensity and spinal mobility. Participants were divided into three groups: group A received Kinesio Taping, as well as conventional therapy; group B received Kinesio Taping, as well as MET and conventional therapy; and group C received MET and conventional therapy. Results revealed that adding MET and Kinesio Taping to traditional treatment seems to reduce pain and increase trunk range of motion.

In patients with NSCLBP (non-specific chronic low back pain), Ghasemi et al. [18] examined the impact of MET, CST, and SMT on postural control. The findings of this study demonstrated that all three techniques—CST, MET, and SMT—are successful in improving postural control in NSCLBP patients, albeit it appears that CST is more successful in improving balance parameters. Standing on one leg with one eye closed while using CST has a larger impact on balance. Additionally, it was shown that the effects of CST persisted even after follow-up. Additionally, Ghasemi and his colleagues [19] evaluated the effects of MET, CST, and SMT on patients’ levels of pain, disability, depression, and quality of life. In the groups SMT, CST, and MET, substantial VAS, BDI, ODI, and SF-36 changes were noted. In the CST group, the changes in VAS, BDI, ODI, and SF-36 at posttreatment and follow-up periods were considerably different from those in the SMT group, and in the MET group, the changes were significantly different from those in the CST group.

For the first time, Wahyuddin and colleagues [26] evaluated patients with probable facet joint origin persistent LBP to assess the immediate effects of MET and LSE. Twenty-one low back pain patients were enlisted, and they were then randomly allocated to either MET or LSE therapy. Only pain scores showed a minor clinically meaningful change following the treatments when the groups were collapsed, but neither lumbar mobility or disability scores.

Quality assessment of included studies

All of the studies that were included were evaluated by two reviewers independently using PEDro scale [25]. Two studies [11, 19] out of seventeen studies (11.8%) had low methodological quality, ten studies (58.8%) had medium methodological quality and thus moderate risk of bias, whereas five studies (29.4%) were of high quality (Table 2).

Discussion

LBP is a major cause of disability with a high global prevalence, affecting 30–80% of the general population [4]. Up to 90% of people will experience LBP at some point, with higher burden reported in lower- and middle-income countries [7]. Recurrence or persistence of LBP symptoms is common, affecting 60–80% of patients. CLBP may result in socioeconomic issues such as long-term incapacity and time away from work [27]. The multifaceted cause of CLBP necessitates multimodal therapy, focusing on patient function, pain, movement, and motor function.

Motor control issues and greater postural instability may be linked to chronic low back pain [28]. People with CLBP frequently have decreased stabilising muscle function and coordination [28]. Manual physiotherapy with manipulative spine treatment is recommended by international guidelines as a nondrug intervention in the management of non-specific low back pain as a therapeutic indication for restoring function [29]. This therapy is indicated as an essential therapeutic component linked to exercise in certain nations, while it is regarded as a primary treatment choice in others [30].

MET is a manipulative osteopathic method used to regain movement and function while reducing discomfort [31, 32]. MET involves vigorous, voluntary muscular contractions and relaxations coupled with the therapist’s passive movement [31,32,33]. Reciprocal inhibition may help relieve joint and muscle sprains, enhancing range of motion [34].

In patients with CLBP, MET dramatically lowers pain intensity levels. Both spinal and supraspinal processes may be responsible for the analgesic effects of MET. During an isometric contraction, both muscle and joint mechanoreceptors are activated. This causes localised activation of the periaqueductal grey, which is involved in the descending regulation of pain, and sympatho-excitation induced by somatic efferents. The simultaneous gating of nociceptive impulses in the dorsal horn caused by mechanoreceptor stimulation then causes nociceptive inhibition in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. By blocking the smaller diameter nociceptive neuronal input at the spinal cord level, MET may be able to reduce pain by stimulating joint proprioceptors through the generation of joint movement or the stretching of a joint capsule [13, 14]. According to systematic review and meta-analysis, Coulter et al. [35] reported that manipulation and mobilisation therapy for the treatment of CLBP, MET looks safe, is probably to lessen discomfort and is likely to enhance specific functions for patients with CLBP.

There are few studies examining the efficacy of MET for NSLBP, either alone or in conjunction with other therapeutic activities (especially trunk stability exercises) [1, 31]. According to a Cochrane evaluation, MET has potential for treating chronic NSLBP and is considered safe when used in conjunction with other therapy methods [31]. To improve therapeutic outcomes for the management of CLBP, however, and to determine if these advantages can be sustained over the long term, more study utilising a sound approach is required [31]. Additionally, a recent scoping review we conducted revealed that the majority of studies that have looked at the effects of MET in CLBP lack methodological rigour, making it impossible to determine whether MET is effective when combined with other therapeutic modalities for the treatment of CLBP [1].

In comparison to DSE alone or conventional therapy, the technique of combining DSE and MET was more effective in reducing pain and correcting lumbar mobility deficits. It also indicated the best satisfaction based on better health status. Studies showing that manual therapy and therapeutic exercises have the significant effect on pain levels, lumbar mobility, and general health status in individuals with chronic NSLBP [8, 36] confirm this conclusion. Niemistö et al. [37] added that the MET, which is utilised to rectify any biomechanical dysfunctions in the lumbar or pelvic regions, may have contributed to the improvement in mobility.

According to this review, individuals with CLBP reported less discomfort after using the muscle energy approach. This result supports earlier research [1, 2, 11, 16, 17, 30]. They also found that using the muscular energy approach helped patients with low back pain to feel less pain in their own trials. According to Chaitow [33], the pain reduction caused by MET is based on neurophysiology. This happens as a result of the agonist muscle’s stretch receptors, known as Golgi tendon. These receptors prevent additional muscular contraction in response to overstretching of the muscle. The Golgi tendon organ is activated by a powerful muscular contraction in response to an equivalent counterforce. An inhibitory motor neuron is encountered by the afferent nerve impulse from the Golgi tendon when it reaches the dorsal root of the spinal cord. Restoring the muscles to their maximum stretch length reduces the increased tension in the afflicted muscles, along with the discomfort and dysfunction that follow [2, 3, 23]. According to Greenman [38], the MET is a regulated manual treatment approach that uses varying levels of intensity in relation to the operator’s clearly shown counterforce. This technique can be employed in situations when high velocity with low amplitude is contraindicated because there is no thrusting involved. In this review, we found that MET alone or in conjunction with other interventions can be beneficial to patients with CLBP.

Limitations

The search should have been broad and include studies since inception. Also CLBP of duration less than 3 months were excluded. The search strategy was limited to English language only. The research results may be impacted by the therapist’s method and any interpersonal variances that exist. To verify the findings, additional in-depth research is required.

Conclusion

MET is a multifunctional approach that is often used to treat joint dysfunction, muscular discomfort, and tightness in the muscles as well as to increase range of motion. This study revealed that in those with chronic low back pain, MET significantly reduces the amount of function disability, improves lumbar spine range of motion, and decreases pain intensity. Therefore, it is recommended that physiotherapists manage patients with CLBP by using MET effectively.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- LBP:

-

Low back pain

- MET:

-

Muscle energy technique

- CLBP:

-

Chronic low back pain

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses

- RCT:

-

Randomised controlled trial

- CST:

-

Cranial sacral therapy

- MEE:

-

McKenzie extension exercise

- SMT:

-

Sensory motor training

- HLVA:

-

High-velocity and low-amplitude technique

- SCS:

-

Strain-counter strain technique

- DSE:

-

Dynamic stabilisation exercise

- LSE:

-

Lumbar stabilisation exercise

- SE:

-

Stability exercise

- FNP:

-

Proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation

- SS:

-

Static stretching

- TENS:

-

Transcutaneous electrical stimulation

- US:

-

Ultrasound

- MRF:

-

Myofascial release

- PME:

-

Pilate mat exercise

- SSE:

-

Stretching and strengthening exercises

- ODI:

-

Oswestry Impairment Index

- RMDQ:

-

Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire

- MODQ:

-

Modified Oswestry Disability Questionnaire

- SIJD:

-

Sacroiliac joint dysfunction

- VAS:

-

Visual Analog Scale

- NPS:

-

Neuropathic Pain Scale

- NRS:

-

Numerical Rating Scale

- SF-MPQ:

-

Short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire

- QBPDS:

-

Quebec back pain disability scale

- MPI:

-

Multidimensional Pain Inventory

- OMPSQ:

-

Örebro Musculoskeletal Pain Questionnaire

- CSE:

-

Classical strength exercises

- NPRS:

-

Numeric Pain Rating Scale

- NSCLBP:

-

Non-specific chronic low back pain

- BDI:

-

Beck Depression Inventory

- HVLA:

-

High-velocity low-amplitude techniques

References

Ahmed UA, Maharaj SS, Van Oosterwijck J. Effects of dynamic stabilization exercises and muscle energy technique on selected biopsychosocial outcomes for patients with chronic non-specific low back pain: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. Scand J Pain. 2021;21(3):495–511. https://doi.org/10.1515/sjpain-2020-0133.

Santos GK, de Gonçalves Oliveira R, de Campos Oliveira L, de Oliveira C Ferreira C, Andraus RA, Ngomo S, Fusco A, Cortis C, DA Silva RA. Effectiveness of muscle energy technique in patients with nonspecific low back pain: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2022;58(6):827–37.

Szulc P, Wendt M, Waszak M, Tomczak M, Cieślik K, Trzaska T. Impact of McKenzie method therapy enriched by muscular energy techniques on subjective and objective parameters related to spine function in patients with chronic low back pain. Med Sci Monit Int Med J Exp Clin Res. 2015;21:2918–32. https://doi.org/10.12659/MSM.894261.

Hoy D, March L, Brooks P, et al. The global burden of low back pain: estimates from the Global Burden of Disease 2010 Study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(6):968–74. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204428.

Wu A, March L, Zheng X, et al. Global low back pain prevalence and years lived with disability from 1990 to 2017: estimates from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8(6):299. https://doi.org/10.21037/atm.2020.02.175.

D’hooge R, Cagnie B, Crombez G, Vanderstraeten G, Achten E, Danneels L. Lumbar muscle dysfunction during remission of unilateral recurrent nonspecific low-back pain: evaluation with muscle functional MRI. Clin J Pain. 2013;29(3):187–94. https://doi.org/10.1097/AJP.0b013e31824ed170.

Hartvigsen J, Hancock MJ, Kongsted A, et al. What low back pain is and why we need to pay attention. Lancet Lond Engl. 2018;391(10137):2356–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30480-X.

Foster NE, Anema JR, Cherkin D, et al. Prevention and treatment of low back pain: evidence, challenges, and promising directions. Lancet Lond Engl. 2018;391(10137):2368–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30489-6.

Campbell P, Bishop A, Dunn KM, Main CJ, Thomas E, Foster NE. Conceptual overlap of psychological constructs in low back pain. Pain. 2013;154(9):1783–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2013.05.035.

Knobloch K, Yoon U, Vogt PM. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement and publication bias. J Cranio-Maxillo-fac Surg Off Publ Eur Assoc Cranio-Maxillo-fac Surg. 2011;39(2):91–2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcms.2010.11.001.

Dhinkaran M, Sareen A, Arora T. Comparative analysis of muscle energy technique and conventional physiotherapy in treatment of sacroiliac joint dysfunction. Indian J Physiother Occup Ther- Int J. 2011;5(4):127–30.

Bindra S, Kumar M, Singh PP, Singh J. A study on the efficacy of muscle energy technique as compared to conventional therapsy in chronic low back pain due to sacroiliac joint dysfunction. Physiother Occup Ther. 2012;6(1).

Ellythy MA. Efficacy of muscle energy technique versus myofascial release on function outcome measures in patients with chronic low back pain. Bull Fac Ph Th. 2012;17(1):51–7.

Ellythy MA. Efficacy of muscle energy technique versus strain counter strain on low back dysfunction. Bull Fac Phys Ther. 2012;17(2):29–35.

Akodu AK, Akinbo SR, Omootunde AS. Comparative effects of muscle energy technique and core stability exercise in the management of patients with non-specific chronic low back pain. Med Sport. 2017;13(1):2860.

Elshinnawy AM, Elrazik RKA, Elatief EEMA. The effect of muscle energy techniques versus cross (X) technique Kinesio Taping to treat chronic low back dysfunction. Int J Ther Rehabil. 2019;26(2):1–8. https://doi.org/10.12968/ijtr.2017.0038.

Fahmy E, Shaker H, Ragab W, Helmy H, Gaber M. Efficacy of spinal extension exercise program versus muscle energy technique in treatment of chronic mechanical low back pain. Egypt J Neurol Psychiatry Neurosurg. 2019;55(1):77. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41983-019-0124-5.

Ghasemi C, Amiri A, Sarrafzadeh J, Dadgoo M, Jafari H. Comparative study of muscle energy technique, craniosacral therapy, and sensorimotor training effects on postural control in patients with nonspecific chronic low back pain. J Fam Med Prim Care. 2020;9(2):978–84. https://doi.org/10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_849_19.

Ghasemi C, Amiri A, Sarrafzadeh J, Dadgoo M, Maroufi N. Comparison of the effects of craniosacral therapy, muscle energy technique, and sensorimotor training on non-specific chronic low back pain. Anaesth Pain Intensive Care. 2020;24(5):532–43. https://doi.org/10.35975/apic.v24i5.1362.

Patel SY, Patil C, Patil S. Comparison of neural tissue mobilization and muscle energy technique on hamstring tightness in chronic low back pain. Medico Leg Update. 2020;20(2):375–9. https://doi.org/10.37506/mlu.v20i2.1133.

Sturion LA, Nowotny AH, Barillec F, et al. Comparison between high-velocity low-amplitude manipulation and muscle energy technique on pain and trunk neuromuscular postural control in male workers with chronic low back pain: a randomised crossover trial. South Afr J Physiother. 2020;76(1):1420. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajp.v76i1.1420.

Bhosale SV, Burungale M. Effectiveness of myofascial release, muscle energy technique and stretching of quadrartus lumborum muscle in patients with non-specific low back pain. J Ecophysiol Occup Health. Published online 2021:132–141. https://doi.org/10.18311/jeoh/2021/28561

Tubassam S, Riaz S, Khan RR, Ghafoor S, Rashid S, Zahra A. Effectiveness of muscle energy technique versus strain counter strain technique on trigger points of quadratus lumborum among low back pain patients. Pak J Med Health Sci. 2021;15(8):2451–3. https://doi.org/10.53350/pjmhs211582451.

Gendy M, Hekal H, Kadah M, Hussien H, Ewais N. Pilate mat exercise versus muscle energy technique on chronic non specific low back pain. Int J Health Sci. 2022;6:3570–83. https://doi.org/10.53730/ijhs.v6nS5.9429.

de Morton NA. The PEDro scale is a valid measure of the methodological quality of clinical trials: a demographic study. Aust J Physiother. 2009;55(2):129–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0004-9514(09)70043-1.

Wahyuddin W, Vongsirinavarat M, Mekhora K, Bovonsunthonchai S, Adisaipoapun R. Immediate effects of muscle energy technique and stabilization exercise in patients with chronic low back pain with suspected facet joint origin: a pilot study. H K Physiother J Off Publ H K Physiother Assoc Ltd Wu Li Chih Liao. 2020;40(2):109–19. https://doi.org/10.1142/S1013702520500109.

Majid K, Truumees E. Epidemiology and natural history of low back pain. Semin Spine Surg. 2008;20(2):87–92. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.semss.2008.02.003.

Shigaki L, Vieira ER, de Oliveira Gil AW, et al. Effects of holding an external load on the standing balance of older and younger adults with and without chronic low back pain. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2017;40(4):284–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmpt.2017.01.007.

Koes BW, van Tulder M, Lin CWC, Macedo LG, McAuley J, Maher C. An updated overview of clinical guidelines for the management of non-specific low back pain in primary care. Eur Spine J Off Publ Eur Spine Soc Eur Spinal Deform Soc Eur Sect Cerv Spine Res Soc. 2010;19(12):2075–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-010-1502-y.

Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, et al. Noninvasive treatments for acute, subacute, and chronic low back pain: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(7):514–30. https://doi.org/10.7326/M16-2367.

Franke H, Fryer G, Ostelo RWJG, Kamper SJ. Muscle energy technique for non-specific low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2:CD009852. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009852.pub2.

Hamilton L, Boswell C, Fryer G. The effects of high-velocity, low-amplitude manipulation and muscle energy technique on suboccipital tenderness. Int J Osteopath Med. 2007;10(2):42–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijosm.2007.08.002.

Herrington L. L. Chaitow, Muscle energy techniques (third ed.), Elsevier, Churchill-Livingstone, New York, NY (2006) 346pp., CD included, Price £42.99, ISBN: 10 0443101140. Man Ther - MAN THER. 2008;13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.math.2007.05.006

Rubinstein SM, Terwee CB, Assendelft WJJ, de Boer MR, van Tulder MW. Spinal manipulative therapy for acute low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;2012(9):CD008880. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD008880.pub2.

Coulter ID, Crawford C, Hurwitz EL, et al. Manipulation and mobilization for treating chronic low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Spine J Off J North Am Spine Soc. 2018;18(5):866–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2018.01.013.

Zafereo J, Wang-Price S, Roddey T, Brizzolara K. Regional manual therapy and motor control exercise for chronic low back pain: a randomized clinical trial. J Man Manip Ther. 2018;26(4):193–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/10669817.2018.1433283.

Niemistö L, Lahtinen-Suopanki T, Rissanen P, Lindgren KA, Sarna S, Hurri H. A randomized trial of combined manipulation, stabilizing exercises, and physician consultation compared to physician consultation alone for chronic low back pain. Spine. 2003;28(19):2185–91. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.BRS.0000085096.62603.61.

Greenman’s Principles of Manual Medicine (Point (Lippincott Williams & Wilkins)) - PDF Drive. Accessed November 30, 2022. https://www.pdfdrive.com/greenmans-principles-of-manual-medicine-point-lippincott-williams-wilkins-e189798204.html

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have contributed equally.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Al Matif, S., Alfageer, G., ALNasser, N. et al. Effectiveness of muscle energy technique on pain intensity and disability in chronic low back patients: a systematic review. Bull Fac Phys Ther 28, 24 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43161-023-00135-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43161-023-00135-w