Abstract

Background

The rapidly developing era of direct-acting antiviral regimens (DAAs) for more than one hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotype had certainly alleviated HCV burden all over the world. Liver fibrosis is the major dramatic complication of HCV infection, and its progression leads to cirrhosis, liver failure, and hepatocellular carcinoma. The impact of DAAs on liver fibrosis had been debatably evaluated with undetermined resolution.

Main body

The aim of this review is to accurately revise the effects of DAA regimens on liver fibrosis which can either be regression, progression, or non-significant association. Liver fibrosis regression is a genuine fact assured by many retrospective and prospective clinical studies. Evaluation could be concluded early post-therapy reflecting the dynamic nature of the process.

Conclusions

The ideal application of DAA regimens in treating HCV has to be accomplished with efficient non-invasive markers in differentiating proper fibrosis evaluation from necroinflammation consequences. Liver biopsy is the gold standard that visualizes the dynamic of fibrosis regression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The advent of DAA therapies against HCV infection is considered by many as the most momentous scientific event taking place in the last few years [1]. Before the developing era of DAAs, HCV infection represented more than 70% of chronic liver disease morbidity and mortality especially in countries with high HCV burden [2]. Nowadays, the outstanding results of DAA therapies had tardily listed HCV in newly reported etiologies of liver diseases [1]. However, the encumbrance of HCV-related liver fibrosis progressing to cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, and decompensated liver disease is still ensuing [3]. The foreseeable end of these HCV-related disorders is linked to the death of the last untreatable case, which is expected to be by 2030 [2]. Nevertheless, the most important question is: are these therapies capable of regressing fibrosis or even stopping the progression of this definite dynamic process?

Main text

Does fibrosis really regress?

Remodeling of liver vascular and regaining the normal lobular architecture upon removal of the incriminating factor is the ultimate hope of liver researchers. As a rule, removing the offender is the most accurate way of reaching a resolution [4]. Accordingly, liver fibrosis—at a certain point—is capable of regression by directly eliminating the cause. Reportedly, on well-targeted early treated autoimmune hepatitis, or hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, regression of fibrosis was a possible prospective [4].

Liver fibrosis is crucially linked to the evolution of certain inflammatory cascades, activated cells, and fibrogenic cytokines [5]. Likewise, in fibrosis regression, the convoluted process of fibrosis regression is reported to be simultaneous with deactivated myofibroblasts, mounting of collagenases enzymes, fibrillar cellular matrix degradation, ending with cell death (senescence and apoptosis of activated stellate cells), and resorption of fibrous septa [6]. Concerning cirrhosis, a more complex end-stage fibrosis, it comprises angiogenesis, necro-inflammation, innate immunity, oxidative stress, tissue hypoxia, and bacterial translocation [7]. Accordingly, regression of fibrosis rather than cirrhosis is considered as a likely prospective. Nevertheless, liver fibrosis regression is not guaranteed to take place on treating the offending agent. Many factors had been demarcated to be of influence on the occurrence of fibrosis regression process: individual’s age, genetic and epigenetic factors, and rate of fibrosis progression (slow or rapid fibrosis), or disease-related factors like etiology and staging of chronic liver disease [8,9,10,11,12].

For liver fibrosis to be evitable, interference should be at a certain time; otherwise, no regression is predictable. The point of no return is that at which liver fibrosis progression is inevitable [13]. The cause might be structural extensive crosslinks developed in collagen, the fibrotic bands consisting mainly of fibrillar collagen, as the collagen bands mature. Some of these crosslinks are irreversible and cannot be degraded by the normal collagenases representing a point of unavoidable fibrosis progression [13].

Evaluation of fibrosis

In the era of interferon (IFN), liver biopsy was the most accountable determinant of treatment decision as a precise measure of liver fibrosis [14].

The contemporary protocols of DAA HCV therapies had adopted reliance on non-invasiveness [15, 16]. The currently handled non-invasive hybrid clinical and laboratory scores of liver fibrosis had performed poorly inaccurate, with failure to distinguish the stages of the dynamic evolutions of liver fibrosis. Moreover, the performance of the more advanced imaging measures that assess liver stiffness (LS) with a fibroscan device like transient elastography (TE), shear wave (SW), acoustic radiation force impulse elastography (ARFI), and magnetic resonance elastography (MRE) [15, 16]. Eventually, there is no perfect one test solution, as serum markers are good at the ends but too soft in the middle. It was found that to be more effective, several tests have to be used together, such as 2 biomarker tests or one biomarker and an elastography test [17].. Despite the high costs, tuning to MRI elastography is said to be promising [18].

The substantial necessity of a widely available accurate, reproductive, and dynamic measure of liver fibrosis progression, and likewise regression, is still representing an unmet need in hepatology research.

It is noteworthy to mention that the difference between liver fibrosis stages is a qualitative rather than a quantitative linear measure, as the amounts of deposited collagens in each stage are not the multiple of the previous stage [19]. Accordingly, more collagenases are needed in late fibrosis stages than earlier ones [9]. Similarly, the non-linearity of collagen deposition in relation to the time interval is evidently clear. Notably, the changes in LS measurement in advanced stages might be within the same stage of fibrosis for the wide included range of numbers [20].

Histopathological features of fibrosis regression

There was no consensus for the proposed histological scoring system for chronic viral hepatitis post-treatment. Histological evaluations are better performed on paired liver biopsies: one obtained before initiation of the therapy and the other at least 6 months after the end of treatment (EOT). In the previous studies, regression was defined as a decrease of at least one point in either METAVIR or histology activity index (HAI) score from baseline to post-treatment evaluation [21, 22].

Fibrosis stage was assessed using the four stages METAVIR fibrosis scoring system [23]. Subsequently, stage 4 cirrhosis was further subdivided into three subgroups based on the thickness of fibrous septa and the size of the nodules that properly correlated with the clinical stage as well as the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence after curative resection. Stage 4A is characterized by mild cirrhosis with thin septa (definite or probable), stage 4B is moderate cirrhosis showing at occasional broad fibrous septa, and stage 4C refers to severe cirrhosis in which at least one very broad septum or many micronodules are present [24, 25]. The grade of necro-inflammatory activity was assessed using the HAI criteria with a maximum score of HAI is 18 [26].

Hepatic repair complex is another scoring system that depends on the presence of relevant histological findings that implies a regression of cirrhosis. This system relied on the histological findings of perforated delicate septa, isolated thick collagen fibers, thin periportal fibrous spikes, hepatic vein remnants with prolapsed hepatocytes, split septa interrupted by clusters or cords of hepatocytes, and aberrant parenchymal veins [27].

The Beijing classification, P-I-R Score (predominantly regressive, indeterminate, and predominantly progressive), is a unique method that provides a dynamic evaluation of the fibrosis course progression versus regression. This system was proposed by Sun et al., in the evaluation of chronic HBV pre- and post-therapy [28]. Fibrosis was assessed using routine hematoxylin and eosin, reticulin, and trichrome stains. The cases were sub-classified into predominantly progressive fibrosis in which most fibrous septa were broad, with loosely aggregated pale stained collagen infiltrated by inflammatory cells and ductular reactions; indeterminate fibrosis midway between progressive and regressive fibrosis; and predominantly regressive in which most fibrous septa showed thin, dense, and acellular stroma lack capillary vascular proliferation and staining deeply on trichrome stain.

Since liver cirrhosis is a heterogeneous process, future efforts are recommended to incorporate features of regression and validate a staging system for better assessment of fibrosis and necro-inflammation regression in chronic liver diseases [29].

Advancement of the digital pathology and the application of morphometry in the assessment of collagen proportionate area (CPA) was impressive in the detection of fibrosis regression post-HCV treatment [30]. In addition, second harmonic generation/two-photon excitation fluorescence (SHG/TPEF), a quantitative assessment of liver fibrosis width, assumed to be the most predictive feature indicative of fibrosis regression [31, 32].

Fibrosis regression in recovered HCV patients

Fibrosis regression evaluation post-treating HCV should be done only after at least 1 year of achieving sustained virological response (SVR). Earlier performed studies should not be significantly considered for their inaccurate conclusions.

In the IFN era

Liver biopsy was the gold standard relied on for proper pretreatment staging of liver fibrosis and treatment decisions. Most studies performed for post-treatment evaluation of fibrosis were dependent on paired liver biopsies [14].

The remarkable, pooled study of Poynard et al. tested the effect of different types of IFN containing regimens on liver fibrosis and even cirrhosis. The study enrolled 4493 patients from four randomized trials of pegylated (PEG) IFN alfa-2b (IFN α2b) alone, in combination with ribavirin (RBV), or of combined IFN α2b and (RBV) [33,34,35,36]. At the initial biopsy, 75% had no significant fibrosis while 25% had significant fibrosis with the mean METAVIR fibrosis stage ranging from 1.3 to 1.5. The SVR rate varied significantly from 5 to 63% according to the regimen. In patients with SVR, there was less fibrosis progression (7% versus 17% and 21% in relapsers and non-responders, respectively). However, independent of achieving an SVR, young patients (< 40 years old) with low body mass index (less than 27) and who had a low fibrosis stage at baseline are at low risk of fibrosis progression. A paired biopsy was available from 3010 patients with a 20-month mean duration between the biopsies. The histological response showed improvement in the fibrosis stage in 55% of patients, no change in 31%, and an upstage in 14% of the cases. In addition, fibrosis progression was the worst in patients treated with IFN for 24 weeks. The second biopsy stated that cirrhosis was observed in 6% versus 10% of patients treated with reinforced regimens compared to non-treated patients. Even more, nearly half of the treated patients showed a reversal of cirrhosis; however, the difference was a one-stage change [37]. Another study enrolled 150 patients who achieved SVR after a combinational treatment therapy of IFN α2b and RBV. Pre-treatment liver biopsies highlighted the stage of fibrosis to be stage 2 and 6 in 77% and 11%, respectively. A 5-year follow-up documented a noteworthy fibrosis regression in about 81.5%. Of the 12 patients with advanced fibrosis/cirrhosis, ten had decreased fibrosis scores in a range of two points or greater [38]. However, a large long-term (10 years) observational study assessing the regression of fibrosis on IFN-treated HCV patients relying on non-invasive liver fibrosis parameters (APRI score and FIB4 formula) had also addressed remarkable regression proven in those with SVR achievement [39].

In DAA era

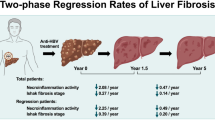

The advent of DAA therapies was associated with the prevalence of the non-invasive measures of liver fibrosis staging and had eliminated the role of liver biopsy [40]. Accordingly, most studies searching for fibrosis regression are currently dependable on paired or bi-paired non-invasive measures [15,16,17,18,19]. In a study carried by Knop et al. on 54 cirrhotic patients revealed a reduction of LS in 88% and 57% of DAA-treated patients after 6 months of achieving SVR using TE and AFRI techniques, respectively [41]. Based on the non-invasive scores, liver transplant recipients were also evaluated for fibrosis reversal on a 3-month interval of DAA therapy of HCV [42]. Martini et al. monitored 125 post-transplanted patients treated with DAAs using TE and found a stepwise decline of LS from 20.4 to 17.5 to 14.0 kPa at 6 and 12 months, respectively [43]. Another study on 112 patients received IFN/DAAs post-transplantation and followed up for 1 year demonstrated that a nearly 43.2% and 72–85% of cirrhotic and remaining stages patients showed histological evidence of fibrosis regression at least 1-metavir stage, respectively [44]. A 6-month interval study performed on 51 post-transplant patients followed up for 1 year after achieving SVR using SW, TE, and ARFI showed at least a 20% decrease in LS compared with baseline [45]. Despite the short-term follow-up, Elraziky et al. in their study which was dependent on TE, PRI, and FIB 4 in the assessment of fibrosis revealed fibrosis regression in 27.5% of patients 3 months after SVR. Treated cirrhotic patients experienced fibrosis regression irrespective of their therapy regimens, whereas fibrosis regression was dependent on achieving SVR in cirrhotic patients [46]. A similar prospective study adopting SW was performed serially for 6 months post-treatment pledging the assumption of early regression post-DAA therapies [47]. An 18-month study had evaluated the changes in LS through TE, APRI, and FIB4 scores following DAA therapies, revealing a significant alleviation of liver stiffness among SVR achievers [48]. ARFI was the nominated measure of LS in the study of Chen et al., who reported a significant decrease in fibrosis measures on 24 weeks post-treatment follow-up [49]. Nearly 25.5% of cirrhotic patients followed up for 1 year declined to 18.1% on TE [50]. Prakash et al. demonstrated that 39% of cirrhotic patients declined to < 2.67 on FIB 4 monitoring technique [51]. The most promising MRE had been adopted for a short-term study of assessing fibrosis regression coinciding with SVR detecting. Surprisingly, a significant reduction in the fibrosis burden was evidenced by an acute lessening in liver T1, T2, and T2* and a liver perfusion upsurge [18].

Soliman et al. had assessed the degree of fibrosis regression through TE, in a 1-year interval, and had substantially confined the role of DAAs in regression of fibrosis either with or without IFNs [12]. Another 1-year comparative retrospective Egyptian study had delineated a higher rate of regression of fibrosis in DAAs successfully treated cases (52.5%) than those who were responsive to IFN treatment (23.3%). In this study, reliance was based on TE for the DAA-treated group versus liver biopsy in the IFN group [52].

However, all these studies have raised a significant concern about the credibility of all used parameters in genuine assessment of fibrosis regression, or these are the penalties of alleviated necroinflammation following the direct viral effects of these drugs. So, despite the marvelous achievement of the therapeutic goal of DAAs, more meticulous judging measures are still needed for better appraisal of the proposed residual liver disease burden following the end of therapy. Assumptions had to be delineated for planning better strategies directed to HCV-related liver disease burden complete elimination.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) post-DAA versus IFN regimens

A meta-analysis of twelve studies showed a reduction in HCC risk of 76% in patients achieving SVR following IFN therapy [53]. On the other hand, conflicting data appeared regarding the risk of HCC occurrence and recurrence post-DAAs treatment. Three studies reported that DAA-induced SVR did not reduce the occurrence and recurrence of HCC; however, these studies were small-size, single-centered of short-term follow-up cohorts [54,55,56]. The possible explanation is that a rapid HCV suppression mediated immunological changes and induced a more aggressive HCC. Furthermore, HBV reactivation in the setting of DAA use has been reported which may co-operate in HCC development [57]. The follow-up of 344 cirrhotic patients without HCC treated with DAAs for 6 months revealed the occurrence of HCC in 9/285 patients (3.2%) and recurrence in 17/59 patients (28.8%). Conti et al. assumed the high HCC risk was related to the Child-Pugh class and prior HCC history rather than HCV genotype or DAA regimen [55]. Other reports suggested the risk of HCC was 9% within 6 months and 7.4% within 12 months follow-up [54, 56]. In contrast, large cohort studies have demonstrated a reduced risk of HCC in patients achieving SVR post-DAA regimen [58,59,60]. The risk of HCC was 1.2% among 22,500 patients treated with DAAs of which 0.8% had achieved SVR. The main co-factors for the development of HCC in that study were liver cirrhosis and failure of achieving SVR [58]. In a retrospective study including more than 60,000 HCV patients treated with antiviral therapy either DAAs, IFN-based regimens, or combined regimens, achievement of SVR was the main factor associated with low HCC risk regardless of the antiviral regimen [60]. A systematic meta-analysis of 26 observational studies on HCC occurrence following different anti-viral therapies (IFN = 17, DAAs = 9 studies) reported higher HCC risk in DAA-treated patients compared to IFN. However, the higher risk was alleviated after adjustment for study follow-up and age. DAA-treated patients were older and had a short follow-up duration [61]. Additionally, in a large cohort of 17,836 HCV-infected either treated with IFN or DAAs revealed a significantly higher HCC incidence rate than IFN treated patients. DAA-treated patients were of older age with elevated serum AFP and had liver cirrhosis, the main risk factors for HCC occurrence. A sub-analysis in cirrhotic patients showed a high risk of HCC in untreated patients with an equal risk in both treated patients [59]. Mariño et al. reported a 3.73% risk of developing HCC in 1123 cirrhotic patients treated with DAAs; the risk was higher in patients without SVR, who had more severe diseases (Child B or C, decompensation or high liver stiffness) and atypical nodules [62].

The risk of HCC recurrence occurred at a similar rate in patients treated with DAA or IFN regimens after adjustment of the cofactors [61, 63, 64]. The cumulative incidence of HCC recurrence was dependent on the achievement of SVR in both arms of treatment [63]. Moreover, in a study including 149 liver-transplanted candidates who underwent initial complete response to loco-regional therapies for HCV-related HCC, DAA therapy was associated with reduced risk of waitlist dropout due to tumor progression or death [65]. However, in a prospective cohort that included 333 successfully treated HCC patients, divided into 60 patients who received DAAs and 273 patients who were DAA-untreated after HCC ablation, a higher risk of HCC recurrence appeared in post-DAA-treated patients versus untreated patients. In addition, the risk was higher in patients treated with transarterial chemoembolization rather than curative measures. The main cofounders affecting HCC recurrence were age, male gender, mean tumor size, and the time interval between complete HCC ablation and occurrence of HCC recurrence [66].

Fibrosis regression and the risk of HCC

In a study by Crissien et al. five patients developed HCC after SVR over the emerging 5 years; two of them experienced fibrosis regression by TE [67]. In addition, Chekuri et al. suggested that fibrosis regression reached its plateau about 1 year after SVR [68]. Moreover, the fibrosis regression does not exclude the development of HCC years after treatment [67, 68]. Therefore, due to the lack of sufficient information about the possible risk of HCC reduction after SVR with the DAAs, patients, particularly with advanced fibrosis namely F3/F4, should undergo a regular screening of HCC [69].

Conclusions

DAA regimens represent a breakthrough of this century. DAAs have demonstrated genuine significant impacts on all HCV-related health hazards, initially sourced from liver fibrosis regression which is considered the milestone of chronic liver disease with its complications. It was assumed that the more time passed, the more significant reported changes on fibrosis appeared. However, DAAs have proved high accuracy in the early distinguishing of dynamic fibrosis regression changes. However, proper judging on the effect of DAA therapies of HCV on liver disease burden should be more furtherly evaluated on large-scale cohorts, along with longer durations. The unmet need of a single reproductive test equating the accuracy of liver biopsy for evaluating fibrosis rather than necroinflammation should be the urge of upcoming research.

Availability of data and materials

Availability of data and material is present from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ARFI:

-

Acoustic radiation force impulse elastography

- CPA:

-

Collagen proportionate area

- DAAs:

-

Direct-acting antiviral regimens

- EOT:

-

End of treatment

- HAI:

-

Histology activity index

- HCV:

-

Hepatitis C virus

- LS:

-

Liver stiffness

- MRE:

-

Magnetic resonance elastography

- P-I-R Score:

-

Progressive, indeterminate, and regressive score

- SHG/TPEF:

-

Second harmonic generation/two-photon excitation fluorescence

- SVR:

-

Sustained virological response

- SW:

-

Shear wave

- TE:

-

Transient elastography

- HCC:

-

Hepatocellular carcinoma

References

Musa NI, Mohamed IE, Abohalima AS (2020) Impact of treating chronic hepatitis C infection with direct-acting antivirals on the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence. Egyptian Liver J 10(1):26. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43066-020-00035-x

Gomaa A, Allam N, Elsharkawy A, El Kassas M, Waked I (2017) Hepatitis C infection in Egypt: prevalence, impact and management strategies. Hepat Med 9:17–25. https://doi.org/10.2147/HMER.S113681

Meringer H, Shibolet O, Deutsch L (2019) Hepatocellular carcinoma in the post-hepatitis C virus era: should we change the paradigm? World J Gastroenterol 25(29):3929–3940. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v25.i29.3929

Zoubek ME, Trautwein C, Strnad P (2017) Reversal of liver fibrosis: from fiction to reality. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 31(2):129–141. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpg.2017.04.005

Pinzani M (2015) Pathophysiology of liver fibrosis. Dig Dis 33(4):492–497. https://doi.org/10.1159/000374096

Povero D, Busletta C, Novo E, di Bonzo LV, Cannito S, Paternostro C, Parola M (2010) Liver fibrosis: a dynamic and potentially reversible process. Histol Histopathol 25(8):1075–1091. https://doi.org/10.14670/hh-25.1075

Saffioti F, Pinzani M (2016) Development and regression of cirrhosis. Dig Dis 34(4):374–381. https://doi.org/10.1159/000444550

Freeman AJ, Dore GJ, Law MG, Thorpe M, Von Overbeck J, Lloyd AR, Marinos G, Kaldor JM (2001) Estimating progression to cirrhosis in chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology 34(4):809–816. https://doi.org/10.1053/jhep.2001.27831

Arthur MJP (2002) Reversibility of liver fibrosis and cirrhosis following treatment for hepatitis C. Gastroenterology 122(5):1525–1528. https://doi.org/10.1053/gast.2002.33367

Thein H-H, Yi Q, Dore GJ, Krahn MD (2008) Estimation of stage-specific fibrosis progression rates in chronic hepatitis C virus infection: a meta-analysis and meta-regression. Hepatology 48(2):418–431. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.22375

Tachi Y, Hirai T, Ishizu Y, Honda T, Kuzuya T, Hayashi K, Ishigami M, Goto H (2016) α-Fetoprotein levels after interferon therapy predict regression of liver fibrosis in patients with sustained virological response. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 31(5):1001–1008. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgh.13245

Hanan S, Dina Z, Marwa S, Manal H, Rehab B, Nehad H, Amal S, Sherief A-E (2020) Predictors for fibrosis regression in chronic HCV patients after the treatment with DAAS: results of a real-world cohort study. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets 20(1):104–111. https://doi.org/10.2174/1871530319666190826150344

Sun M, Kisseleva T (2015) Reversibility of liver fibrosis. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol 39(Suppl 1 (0 1)):S60–S63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinre.2015.06.015

Ellis EL, Mann DA (2012) Clinical evidence for the regression of liver fibrosis. J Hepatol 56(5):1171–1180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2011.09.024

Abdelsameea E, Alsebaey A, Abdel-Razek W, Ehsan N, Morad W, Salama M, Waked I (2020) Elastography and serum markers of fibrosis versus liver biopsy in 1270 Egyptian patients with hepatitis C. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 32(12):1553–1558. https://doi.org/10.1097/MEG.0000000000001672

Sigrist RMS, Liau J, Kaffas AE, Chammas MC, Willmann JK (2017) Ultrasound elastography: review of techniques and clinical applications. Theranostics 7(5):1303–1329. https://doi.org/10.7150/thno.18650

Nallagangula KS, Nagaraj SK, Venkataswamy L, Chandrappa M (2017) Liver fibrosis: a compilation on the biomarkers status and their significance during disease progression. Future Sci OA 4(1):FSO250. https://doi.org/10.4155/fsoa-2017-0083

Bradley C, Scott RA, Cox E, Palaniyappan N, Thomson BJ, Ryder SD, Irving WL, Aithal GP, Guha IN, Francis S (2019) Short-term changes observed in multiparametric liver MRI following therapy with direct-acting antivirals in chronic hepatitis C virus patients. Eur Radiol 29(6):3100–3107. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-018-5788-1

Masugi Y, Abe T, Tsujikawa H, Effendi K, Hashiguchi A, Abe M, Imai Y, Hino K, Hige S, Kawanaka M, Yamada G, Kage M, Korenaga M, Hiasa Y, Mizokami M, Sakamoto M (2017) Quantitative assessment of liver fibrosis reveals a nonlinear association with fibrosis stage in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatol Commun 2(1):58–68. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep4.1121

Castéra L, Vergniol J, Foucher J, Le Bail B, Chanteloup E, Haaser M, Darriet M, Couzigou P, de Lédinghen V (2005) Prospective comparison of transient elastography, Fibrotest, APRI, and liver biopsy for the assessment of fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology 128(2):343–350. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2004.11.018

Cheng C-H, Chu C-Y, Chen H-L, Lin IT, Wu C-H, Lee Y-K, Hu P-J, Bair M-J (2020) Direct-acting antiviral therapy of chronic hepatitis C improves liver fibrosis, assessed by histological examination and laboratory markers. J Formos Med Assoc doi:https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfma.2020.11.018, 120, 5, 1259, 1268

Sun Y-M, Chen S-Y, You H (2020) Regression of liver fibrosis: evidence and challenges. Chin Med J 133(14):1696–1702. https://doi.org/10.1097/CM9.0000000000000835

Bedossa P, Poynard T (1996) An algorithm for the grading of activity in chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology 24 (2):289-293. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.510240201

Kim MY, Cho MY, Baik SK, Park HJ, Jeon HK, Im CK, Won CS, Kim JW, Kim HS, Kwon SO, Eom MS, Cha SH, Kim YJ, Chang SJ, Lee SS (2011) Histological subclassification of cirrhosis using the Laennec fibrosis scoring system correlates with clinical stage and grade of portal hypertension. J Hepatol 55(5):1004–1009. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2011.02.012

Kim SU, Oh HJ, Wanless IR, Lee S, Han K-H, Park YN (2012) The Laennec staging system for histological sub-classification of cirrhosis is useful for stratification of prognosis in patients with liver cirrhosis. J Hepatol 57(3):556–563. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2012.04.029

Ishak K, Baptista A, Bianchi L, Callea F, De Groote J, Gudat F, Denk H, Desmet V, Korb G, MacSween RNM, Phillips MJ, Portmann BG, Poulsen H, Scheuer PJ, Schmid M, Thaler H (1995) Histological grading and staging of chronic hepatitis. J Hepatol 22(6):696–699. https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-8278(95)80226-6

Wanless IR, Nakashima E, Sherman M (2000) Regression of human cirrhosis. Morphologic features and the genesis of incomplete septal cirrhosis. Archiv Pathol Lab Medicine 124(11):1599–1607. https://doi.org/10.1043/0003-9985(2000)124<1599:rohc>2.0.co;2

Sun Y, Zhou J, Wang L, Wu X, Chen Y, Piao H, Lu L, Jiang W, Xu Y, Feng B, Nan Y, Xie W, Chen G, Zheng H, Li H, Ding H, Liu H, Lv F, Shao C, Wang T, Ou X, Wang B, Chen S, Wee A, Theise ND, You H, Jia J (2017) New classification of liver biopsy assessment for fibrosis in chronic hepatitis B patients before and after treatment. Hepatology 65 (5):1438-1450. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.29009

Lo RC, Kim H (2017) Histopathological evaluation of liver fibrosis and cirrhosis regression. Clin Mol Hepatol 23(4):302–307. https://doi.org/10.3350/cmh.2017.0078

D’Ambrosio R, Aghemo A, Rumi MG, Ronchi G, Donato MF, Paradis V, Colombo M, Bedossa P (2012) A morphometric and immunohistochemical study to assess the benefit of a sustained virological response in hepatitis C virus patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology 56 (2):532-543. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.25606

Wang B, Sun Y, Zhou J, Wu X, Chen S, Wu S, Liu H, Wang T, Ou X, Jia J, You H (2018) Advanced septa size quantitation determines the evaluation of histological fibrosis outcome in chronic hepatitis B patients. Mod Pathol 31(10):1567–1577. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-018-0059-x

Sun Y, Zhou J, Wu X, Chen Y, Piao H, Lu L, Ding H, Nan Y, Jiang W, Wang T, Liu H, Ou X, Wee A, Theise ND, Jia J, You H (2018) Quantitative assessment of liver fibrosis (qFibrosis) reveals precise outcomes in Ishak “stable” patients on anti-HBV therapy. Sci Rep 8(1):2989–2989. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-21179-2

McHutchison JG, Gordon SC, Schiff ER, Shiffman ML, Lee WM, Rustgi VK, Goodman ZD, Ling M-H, Cort S, Albrecht JK (1998) Interferon alfa-2b alone or in combination with ribavirin as initial treatment for chronic hepatitis C. N Engl J Med 339(21):1485–1492. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199811193392101

Poynard T, Marcellin P, Lee SS, Niederau C, Minuk GS, Ideo G, Bain V, Heathcote J, Zeuzem S, Trepo C, Albrecht J (1998) Randomised trial of interferon α2b plus ribavirin for 48 weeks or for 24 weeks versus interferon α2b plus placebo for 48 weeks for treatment of chronic infection with hepatitis C virus. Lancet 352(9138):1426–1432. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(98)07124-4

Lindsay KL, Trepo C, Heintges T, Shiffman ML, Gordon SC, Hoefs JC, Schiff ER, Goodman ZD, Laughlin M, Yao R, Albrecht JK (2001) A randomized, double-blind trial comparing pegylated interferon alfa-2b to interferon alfa-2b as initial treatment for chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology 34(2):395–403. https://doi.org/10.1053/jhep.2001.26371

Manns MP, McHutchison JG, Gordon SC, Rustgi VK, Shiffman M, Reindollar R, Goodman ZD, Koury K, Ling M-H, Albrecht JK (2001) Peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin compared with interferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin for initial treatment of chronic hepatitis C: a randomised trial. Lancet 358(9286):958–965. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06102-5

Poynard T, McHutchison J, Manns M, Trepo C, Lindsay K, Goodman Z, Ling MH, Albrecht J (2002) Impact of pegylated interferon alfa-2b and ribavirin on liver fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology 122(5):1303–1313. https://doi.org/10.1053/gast.2002.33023

George SL, Bacon BR, Brunt EM, Mihindukulasuriya KL, Hoffmann J, Di Bisceglie AM (2009) Clinical, virologic, histologic, and biochemical outcomes after successful HCV therapy: a 5-year follow-up of 150 patients. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md) 49(3):729–738. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.22694

Lu M, Li J, Zhang T, Rupp LB, Trudeau S, Holmberg SD, Moorman AC, Spradling PR, Teshale EH, Xu F, Boscarino JA, Schmidt MA, Vijayadeva V, Gordon SC, Chronic Hepatitis Cohort Study I (2016) Serum biomarkers indicate long-term reduction in liver fibrosis in patients with sustained virological response to treatment for HCV infection. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 14(7):1044–1055.e1043. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2016.01.009

Lucero C, Brown RS Jr (2016) Noninvasive measures of liver fibrosis and severity of liver disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 12(1):33–40

Knop V, Hoppe D, Welzel T, Vermehren J, Herrmann E, Vermehren A, Friedrich-Rust M, Sarrazin C, Zeuzem S, Welker MW (2016) Regression of fibrosis and portal hypertension in HCV-associated cirrhosis and sustained virologic response after interferon-free antiviral therapy. J Viral Hepat 23(12):994–1002. https://doi.org/10.1111/jvh.12578

Iacob S, Cerban R, Pietrareanu C, Ester C, Iacob R, Gheorghe C, Popescu I, Gheorghe L (2018) 100% sustained virological response and fibrosis improvement in real-life use of direct acting antivirals in genotype-1b recurrent hepatitis C following liver transplantation. J Gastrointestinal Liver Dis: JGLD 27(2):139–144. https://doi.org/10.15403/jgld.2014.1121.272.100

Martini S, Sacco M, Strona S, Arese D, Tandoi F, Dell Olio D, Stradella D, Cocchis D, Mirabella S, Rizza G, Magistroni P, Moschini P, Ottobrelli A, Amoroso A, Rizzetto M, Salizzoni M, Saracco GM, Romagnoli R (2017) Impact of viral eradication with sofosbuvir-based therapy on the outcome of post-transplant hepatitis C with severe fibrosis. Liver Int 37 (1):62-70. https://doi.org/10.1111/liv.13193

Mauro E, Crespo G, Montironi C, Londoño M-C, Hernández-Gea V, Ruiz P, Sastre L, Lombardo J, Mariño Z, Díaz A, Colmenero J, Rimola A, Garcia-Pagán JC, Brunet M, Forns X, Navasa M (2018) Portal pressure and liver stiffness measurements in the prediction of fibrosis regression after sustained virological response in recurrent hepatitis C. Hepatology 67 (5):1683-1694. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.29557

Alem SA, Said M, Anwar I, Abdellatif Z, Elbaz T, Eletreby R, AbouElKhair M, El-Serafy M, Mogawer S, El-Amir M, El-Shazly M, Hosny A, Yosry A (2018) Improvement of liver stiffness measurement, acoustic radiation force impulse measurements, and noninvasive fibrosis markers after direct-acting antivirals for hepatitis C virus G4 recurrence post living donor liver transplantation: Egyptian cohort. J Med Virol 90(9):1508–1515. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.25210

El-Raziky M, Khairy M, Fouad A, Salama A, Elsharkawy A, Tantawy O (2018) Effect of direct-acting agents on fibrosis regression in chronic hepatitis C virus patients’ treatment compared with interferon-containing regimens. J Interf Cytokine Res 38(3):129–136. https://doi.org/10.1089/jir.2017.0137

Kohla MAS, Fayoumi AE, Akl M, Abdelkareem M, Elsakhawy M, Waheed S, Abozeid M (2020) Early fibrosis regression by shear wave elastography after successful direct-acting anti-HCV therapy. Clin Exp Med 20(1):143–148. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10238-019-00597-0

Omar H, Said M, Eletreby R, Mehrez M, Bassam M, Abdellatif Z, Hosny A, Megawer S, El Amir M, Yosry A (2018) Longitudinal assessment of hepatic fibrosis in responders to direct-acting antivirals for recurrent hepatitis C after liver transplantation using noninvasive methods. Clin Transpl 32(8):e13334. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/ctr.13334

Chen S-H, Lai H-C, Chiang IP, Su W-P, Lin C-H, Kao J-T, Chuang P-H, Hsu W-F, Wang H-W, Chen H-Y, Huang G-T, Peng C-Y (2018) Changes in liver stiffness measurement using acoustic radiation force impulse elastography after antiviral therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis C. PLoS One 13(1):e0190455–e0190455. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0190455

Rout G, Nayak B, Patel AH, Gunjan D, Singh V, Kedia S, Shalimar (2019) Therapy with oral directly acting agents in hepatitis C infection is associated with reduction in fibrosis and increase in hepatic steatosis on transient elastography. J Clin Exp Hepatol 9(2):207–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jceh.2018.06.009

Prakash S, Rockey DC (2020) 1006 predictors of poor fibrosis regression after direct acting antiviral therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis C and cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 158(6):S-1302–S-1303. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-5085(20)33918-4

Abdelsameea E, Alsebaey A, Abdel-Samiee M, Abdel-Razek W, Salama M, Waked I (2020) Direct acting antivirals are associated with more liver stiffness regression than pegylated interferon therapy in chronic hepatitis C patients. Expert Review of Anti-infective Therapy:1-7. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14787210.2021.1864326

Morgan RL, Baack B, Smith BD, Yartel A, Pitasi M, Falck-Ytter Y (2013) Eradication of hepatitis C virus infection and the development of hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Intern Med 158(5_Part_1):329–337. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-158-5-201303050-00005

Reig M, Mariño Z, Perelló C, Iñarrairaegui M, Ribeiro A, Lens S, Díaz A, Vilana R, Darnell A, Varela M, Sangro B, Calleja JL, Forns X, Bruix J (2016) Unexpected high rate of early tumor recurrence in patients with HCV-related HCC undergoing interferon-free therapy. J Hepatol 65(4):719–726. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2016.04.008

Conti F, Buonfiglioli F, Scuteri A, Crespi C, Bolondi L, Caraceni P, Foschi FG, Lenzi M, Mazzella G, Verucchi G, Andreone P, Brillanti S (2016) Early occurrence and recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma in HCV-related cirrhosis treated with direct-acting antivirals. J Hepatol 65(4):727–733. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2016.06.015

Cardoso H, Vale AM, Rodrigues S, Gonçalves R, Albuquerque A, Pereira P, Lopes S, Silva M, Andrade P, Morais R, Coelho R, Macedo G (2016) High incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma following successful interferon-free antiviral therapy for hepatitis C associated cirrhosis. J Hepatol 65(5):1070–1071. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2016.07.027

Bersoff-Matcha SJ, Cao K, Jason M, Ajao A, Jones SC, Meyer T, Brinker A (2017) Hepatitis B virus reactivation associated with direct-acting antiviral therapy for chronic hepatitis C virus: a review of cases reported to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration adverse event reporting system. Ann Intern Med 166(11):792–798. https://doi.org/10.7326/M17-0377

Kanwal F, Kramer J, Asch SM, Chayanupatkul M, Cao Y, El-Serag HB (2017) Risk of hepatocellular cancer in HCV patients treated with direct-acting antiviral agents. Gastroenterology 153(4):996–1005.e1001. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2017.06.012

Li DK, Ren Y, Fierer DS, Rutledge S, Shaikh OS, Lo Re Iii V, Simon T, Abou-Samra A-B, Chung RT, Butt AA (2018) The short-term incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma is not increased after hepatitis C treatment with direct-acting antivirals: an ERCHIVES study. Hepatology 67 (6):2244-2253. doi:https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.29707

Ioannou GN, Green PK, Berry K (2017) HCV eradication induced by direct-acting antiviral agents reduces the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. Journal of Hepatology:S0168-8278(0117)32273-32270. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2017.08.030

Waziry R, Hajarizadeh B, Grebely J, Amin J, Law M, Danta M, George J, Dore GJ (2017) Hepatocellular carcinoma risk following direct-acting antiviral HCV therapy: a systematic review, meta-analyses, and meta-regression. J Hepatol 67(6):1204–1212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2017.07.025

Mariño Z, Darnell A, Lens S, Sapena V, Díaz A, Belmonte E, Perelló C, Calleja JL, Varela M, Rodriguez M, Rodriguez de Lope C, Llerena S, Torras X, Gallego A, Sala M, Morillas RM, Minguez B, Llaneras J, Coll S, Carrion JA, Iñarrairaegui M, Sangro B, Vilana R, Sole M, Ayuso C, Ríos J, Forns X, Bruix J, Reig M (2019) Time association between hepatitis C therapy and hepatocellular carcinoma emergence in cirrhosis: relevance of non-characterized nodules. J Hepatol 70(5):874–884. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2019.01.005

Nagata H, Nakagawa M, Asahina Y, Sato A, Asano Y, Tsunoda T, Miyoshi M, Kaneko S, Otani S, Kawai-Kitahata F, Murakawa M, Nitta S, Itsui Y, Azuma S, Kakinuma S, Nouchi T, Sakai H, Tomita M, Watanabe M (2017) Effect of interferon-based and -free therapy on early occurrence and recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol 67(5):933–939. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2017.05.028

Nishibatake Kinoshita M, Minami T, Tateishi R, Wake T, Nakagomi R, Fujiwara N, Sato M, Uchino K, Enooku K, Nakagawa H, Asaoka Y, Shiina S, Koike K (2019) Impact of direct-acting antivirals on early recurrence of HCV-related HCC: comparison with interferon-based therapy. J Hepatol 70(1):78–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2018.09.029

Huang AC, Mehta N, Dodge JL, Yao FY, Terrault NA (2018) Direct-acting antivirals do not increase the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence after local-regional therapy or liver transplant waitlist dropout. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md) 68(2):449–461. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.29855

Lithy RM, Elbaz T, H. Abdelmaksoud A, M. Nabil M, Rashed N, Omran D, Kaseb AO, O. Abdelaziz A, I. Shousha H (2020) Survival and recurrence rates of hepatocellular carcinoma after treatment of chronic hepatitis C using direct acting antivirals. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. https://doi.org/10.1097/MEG.0000000000001972. Online ahead of print

Crissien A, Minteer W, Pan J, Frenette C, Pockros P (2015) Regression of advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis measured by elastography in patients with chronic hepatitis C who achieved sustained virologic response after treatment for HCV (Abstract 108). Presented at the 66th Annual Meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases Boston, MA

Chekuri S, Nickerson J, Bichoupan K, Sefcik R, Doobay K, Chang S, DelBello D, Harty A, Dieterich DT, Perumalswami PV, Branch AD (2016) Liver stiffness decreases rapidly in response to successful hepatitis C treatment and then plateaus. PLoS One 11(7):e0159413–e0159413. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0159413

Khan R, Velpari S, Koppe S (2018) All patients with advanced fibrosis should continue to be screened for hepatocellular carcinoma after sustained virological response of hepatitis C virus. Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken) 12(5):137–139. https://doi.org/10.1002/cld.707

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors of this paper have participated in its drafting and approved the final version submitted. NE and DS wrote the pathological part. MS wrote the hepatology part. All authors acquired and interpreted the collected data. NE and MS revised and edited the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ehsan, N., Sweed, D. & Elsabaawy, M. Evaluation of HCV-related liver fibrosis post-successful DAA therapy. Egypt Liver Journal 11, 56 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43066-021-00129-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43066-021-00129-0