Abstract

In December 2019, a novel respiratory tract infection, from severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), was detected in China that rapidly spread around the world. This virus possesses spike (S) glycoproteins on the surface of mature virions, like other members of coronaviridae. The S glycoprotein is a crucial viral protein for binding, fusion, and entry into the target cells. Binding the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of S protein to angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE 2), a cell-surface receptor, mediates virus entry into cells; thus, understanding the basics of ACE2 and S protein, their interactions, and ACE2 targeting could be a potent priority for inhibition of virus infection. This review presents current knowledge of the SARS-CoV-2 basics and entry mechanism, structure and organ distribution of ACE2, and also its function in SARS-CoV-2 entry and pathogenesis. Furthermore, it highlights ACE2 targeting by recombinant ACE2 (rACE2), ACE2 activators, ACE inhibitor, and angiotensin II (Ang II) receptor blocker to control the SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In December 2019, a newly emerged coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) appeared for the first time in Wuhan, China [1]. Since then, this devastating global health and economic challenge rapidly spread throughout the world and the world health organization (WHO) officially declared it as a global pandemic [2].Genome sequencing analysis of respiratory specimens identified that severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is the cause active pathogen for COVID-19 [3]. According to the WHO statistics, with more than 500,000,000 confirmed cases of COVID-19 and over 6 million deaths by May 2022, SARS-CoV-2 is still the most challenging health issue, globally. Similar to other countries, so far, Iran has been involved in the pandemic by > 7,200,000 and 141,000, COVID-19 cases and deaths, respectively.

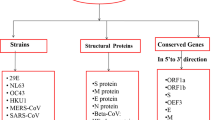

Coronaviruses (CoVs) belong to the Coronaviridae family with a single-stranded, positive-sense RNA (ssRNA) genome inside a large enveloped structure [4, 5]. This huge virus family is divided into four genera named Alpha, Beta, Gamma, and Delta [6, 7]. The coronavirus genus Beta includes highly pathogenic viruses such as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV), Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV), and the novel SARS-CoV-2 and low pathogenic viruses including HCoV-OC43 and HCoV-HKU. Highly pathogenic viruses are commonly zoonotic in origin and cause lower respiratory tract infection while low pathogenic viruses are only endemic in humans and often lead to common colds [8, 9].

Furthermore, genome sequencing of SARS-CoV-2 revealed that this virus has a 29.9 kb genome size which shares around 80% and 96% identity with SARS-CoV and bat coronavirus at nucleic acid level, respectively, suggesting that SARS-CoV-2 has originated from bat SARS-like coronavirus [10, 11]. Although highly pathogenic betacoronaviruses share similarities with each other [12], the novel SARS-CoV-2 infection has a powerful human-to-human transmission capacity [10], which is highly infectious [13, 14], and also effectively evades from immune responses [15] compared to SARS-CoV or MERS-CoV. The clinical manifestations of COVID-19 ranges from mild and common symptoms including fever, dry cough, dyspnea, rhinitis, myalgia and/or fatigue and typically progresses to severe outcomes such as pneumonia, RNAaemia (SARS-CoV-2 RNA in serum), heart injury, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) (10–20% of patients), and death (0.1–15.4% of patients) [16,17,18].

The SARS-CoV-2 infection starts by binding of viral receptors to angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) in the surface of alveolar epithelial cells [19,20,21]. Meanwhile, it has been shown that binding affinity of SARS-CoV-2 to ACE2 is about 10–20 times higher than the interaction of SARS-CoV to this receptor [22]. In addition, this cellular receptor plays a very important role in the pathogenesis of new SARS-CoV-2 infection [23, 24].

Due to recombination of SARS-CoV-2 RNA sequences and involvement of host enzymes in viral RNA editing, the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein has undergone many mutations that led to emergence of different variants including alpha, beta, gamma, delta, omicron, etc., with increased reproduction number (R) and transmission potential [25,26,27].

From 95% of mRNA vaccines efficacy like Pfizer-BioNTech to approximately 60% or less effective vaccines such as Soberana 02 vaccine, all approved vaccines have demonstrated to be effective in reducing the number of mortality and morbidity. Since worldwide administration of different SARS-CoV-2 vaccine platforms, including mRNA, viral vector, inactivated virus, and live attenuated virus vaccines, the elevated neutralizing antibodies in vaccinated individuals raised hope for reducing the risk of infection; however, the appearance of delta and omicron variants has challenged vaccines efficacy [26, 28].

Also, there are no available specific medications with Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approvals against COVID-19, except some SARS-CoV-2-targeting monoclonal antibodies which is just authorized under an emergency use authorization (EUA) and are not approved by FDA. So, finding new protective vaccines and antiviral agents for curing this infection is one of the urgent mankind’s needs. In this review we addressed the role of ACE2 in SARS-CoV-2 infection and pathogenesis. In addition, the efficiency of ACE2 analogs for the treatment of COVID-19 is explained in the present context.

SARS-CoV-2 and cellular receptors

Coronavirus is named for the crown-like spike proteins (S) outside of the viral envelope (Fig. 1A) [29, 30]. Genome analysis studies of CoVs indicated that structural proteins are encoded by the spike (S), envelope, membrane, and nucleocapsid genes (Fig. 1B) [31]. The S protein [1273 amino acids], presented on the surface of mature CoVs in homotrimer form, is the main viral mediator in virus entry into host cells [32]. This viral protein consists of two functional subunits: (i) the S1 subunit, containing a receptor-binding domain (RBD) which mediates virus binding to host cells, and (ii) the S2 subunit that fuses membranes of virus and host cell [33, 34].

Schematic representation of SARS-COV-2 structure and life cycle. A structure of SARS-CoV-2; the crown-like spike proteins (S) are placed on the outside of the viral envelope. B SARS-CoV-2 genomic structure; SARS-CoV-2 genome consists of the 5′-untranslated region (5′-UTR), nonstructural proteins region, structural and accessory proteins region, and the 3′-untranslated region (3′-UTR). C life cycle of SARS-CoV-2 in host cells; virus starts its life cycle by binding of S1 protein to the cellular receptor ACE2 and then proteolytic cleavage in the S protein facilitates the fusion of viral and cellular membranes by S2 protein. After the release of the viral genome into the cytoplasm, viral RNA replicates, and then viral proteins translate from the RNA and then viral proteins and genome are assembled into virions in the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi. Eventually, Virions are transported by vesicles to near the cell membrane and released out of the infected cell by budding from the cytoplasmic membrane

It has been shown that the SARS-CoV-2 S protein shares around 80% identity in amino acid level with the SARS-CoVs protein and these two viruses also show nearly similar 3D structure [35]. However, some reports confirmed that little but functionally important differences at residues 331–524 of SARS-CoV-2-RBD, enable this virus to bind to cellular receptors with higher affinity than SARS-CoV [8, 36,37,38]. The transmembrane protease serine 2 (TMPRSS2) cleaves S protein at the S2´ site, located between S1 and S2. This cleavage leads to extensive structural changes in S2 protein and actives it to fuse with the membrane and completes SARS-CoV-2 internalization through endocytosis process (Fig. 1C). All these data indicate that viral S protein and human ACE2 play important roles in establishing SARS-CoV-2 infection and are required for virus entry [10, 39,40,41]. Furthermore, an in vivo study confirmed that the knockout of the ACE2 gene could inhibit SARS-CoV-2 infection in murine epithelial cells [40]. Thus, blocking of virus attachment to ACE2 receptors can be considered as a therapeutic option.

ACE2 structure and function

In 2000, scientists discovered a new homolog of ACE and named it ACE2. This homolog is encoded by ACE2 gene, placed in chromosome Xp22, and contains 18 exons [42]. ACE2 as a cell-surface receptor, like ACE, is a transmembrane protein that consists of two domains: (i) N-terminal contains a catalytic site, and (ii) C-terminal possesses a transmembrane anchor (Fig. 2A). Structurally, ACE has 2 active catalytic sites while ACE2 possesses only a single active site in the N-terminal domain, and also there is no similarity between the C-terminal domain of ACE2 with ACE [43, 44]. In ACE2, the protease domain (PD) in the N-terminal portion performs all peptidase activities and the C-terminal domain, as a strong anchor, connects the C-terminal domain to the cell membrane and regulates the amino acid transporters trafficking [45].

ACE2 structure and its function in the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS). A ACE2 structure; N-terminal domain includes single peptide, protein cleavage site, and active site and C-terminal domain contain transmembrane alpha-helix. B Schematic overview of ACE2 functions in the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RASS)

Functionally, ACE2 and ACE are carboxypeptidases that play axial roles in renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS) to regulate hemostasis in the human body (Fig. 2B) [46]. ACE2 has only one single catalytic site that acts as a simple carboxypeptidase while its ACE isoform contains two active domains that cleave amino acids, located in the carboxyl end of peptides [47]. However, these structural and functional differences are important in their enzymatic activities. In RAAS, angiotensinogen, a precursor peptide secreted from the liver, is cleaved by renin and converted to angiotensin I (Ang I) decapeptide, then ACE cleaves 2 amino acids from Ang I to produce an angiotensin II (Ang II) octapeptide, while ACE2 converts Ang I to angiotensin (1–9) [Ang (1–9)] by cleaving one amino acid of that. ACE catabolizes Ang (1–9) into Ang (1–7). ACE2 can also cleave Ang II to form Ang (1–7). Ang (1–7) binds to Mas receptors and performs its activity (Fig. 2B) [48, 49].

ACE2, as a negative regulator of the RAS, has vasodilatory, anti-inflammatory, and anti-fibrotic impacts and counter-balances the ACE/AngII/angiotensin receptor 1 (AT1 R) pathway [50, 51]. Apart from ACE2 systemic actions, this enzyme has regulatory effects in the heart, kidney, lung, and gastrointestinal tracts. In this way, ACE2 controls the metabolism of bradykinin in the lungs, orchestrates the amino acid absorption in the kidney and also modulates the insulin secretion from pancreatic cells. This enzyme regulates the homeostasis of amino acids, the expression of peptides, and local innate immune responses in the gut [52]. Furthermore, studying the newly emerged SARS-CoV-2 infection has identified the ACE2 as a crucial receptor for virus entry [53].

Organ distribution of ACE2

ACE2 proteins are active and extensively expressed in a wide range of organs and tissues of the human body. In the respiratory tract, ACE2 widely presents in the epithelium of basal and oral mucosa, nasopharynx, and alveolar epithelial cells of lungs and bronchial and also exerts protective effects on lung [54]. ACE2 prevents bradykinin from binding to its receptor, prohibits releasing pro-inflammatory cytokines, lung injury, and inflammation [55]. Also, it has been shown that acute lung injury and inflammatory lesions in the respiratory tract markedly increased in the ACE2 knockout mice and these implications disappeared after injection of recombinant ACE2 [56]. Furthermore, different organs of the gastrointestinal tract including, the stomach, colon, duodenum, jejunum, and ileum are strongly capable to express ACE2. Besides, the ACE2 localization in the endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells of cardiovascular tissue, the kidney, skin, male testis, and female breast are highly positive for this aminopeptidase [57,58,59]. In contrast, ACE2 is not detectable in lymphoid tissues and hepatobiliary structures including the spleen, thymus, lymph nodes, bone marrow, and even immune system cells [60].

ACE2 and SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis

Respiratory tract cells are the first target for starting SARS-CoV-2 infection because of high expression level of ACE2 [61]. Following infection, virions infect epithelial cells, complete their life cycle, and produce progenies by destroying the infected cells which results in limited lung injury. Then, the local and innate immune cells including dendritic cells and macrophages which serve as sentinel cells present the SARS-CoV-2-infected destroyed cells to adaptive cells [62]. Asymptomatic or mild stages of infection are seen in around 80% of infected individuals [63, 64]. Unfortunately, in 20% of patients, the disease progresses and causes severe respiratory complications including ground-glass opacities, RNAaemia, and ARDS [18, 64, 65]. Severe respiratory symptoms are usually seen in patients who are elderly and have coexisted chronic diseases with weak immune responses and poor respiratory tract function [17, 52]. The cytokine storm resulted from the increased level of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukins (IL-1, IL-6), interferon, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α), as immune response to virus infection, causes severe symptoms in the lung [66,67,68].

Although SARS-CoV-2 is known as a respiratory tract infectious agent, ACE2 distribution in the above-mentioned organs introduces it as a multi-organ pathogen with systemic and respiratory manifestations (Fig. 3) [61]. It has been shown that the presence of ACE2 on the surface of gut cells makes them susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infection and causes symptoms including loss of appetite, anorexia, diarrhea, vomiting, and abdominal pain [69, 70]. In the cardiovascular system, ACE2 as a part of the RAAS system has a protective role, but SARS-CoV-2, when binds to this cellular receptor, may facilitate targeting of myocardial cells for the viral infection [62]. The reported SARS-CoV-2-associated cardiovascular outcomes include myocardial injury, heart failure, myocarditis, hypertension, diabetes, and arrhythmias [16, 71,72,73]. The mild-to-moderate proteinuria is the most common kidney complication in COVID-19 patients while acute kidney injury (AKI) is detectable in the severe form of SARS-CoV-2 infection [74]. Also, SARS-CoV-2 can cause variable skin lesions in > 20% of patients [75, 76]. However, it is not well known that these skin abnormalities may be primarily caused by viral invasion or secondary by induced immune responses and treatments [62]. Also, neurological [77], ocular [78, 79], hematological manifestations [80, 81], and endocrine abnormalities [82] were seen in the COVID-19 patients. Although these suggest that ACE2 may play critical roles in SARS-CoV-2 infection, new and more data are essentially needed for a precise understanding of SARS-CoV-2 pulmonary and extra pulmonary outcomes.

ACE2 and respiratory infections

The COVID-19 symptoms range from an asymptomatic state to mild upper respiratory tract infection and severe pneumonia, ARDS, or even multi organ failure. ARDS is a syndrome characterized by the acute onset of hypoxemia ([PaO2/FiO2] B200 mmHg), with bilateral infiltrates on chest imaging, but without sign of left atrial hypertension [83]. The common risk factors associated with ARDS include pneumonia (virus, bacteria, fungus), aspiration of gastric contents, inhalational injury and sepsis, and major trauma that is classified into direct and indirect lung injury categories [83]. The treatment is mainly based on lung-protective ventilatory strategy and mortality has been markedly reduced with supportive treatment. However, there is no suggested pharmacological treatment [84]. An observational study in Wuhan, China, showed that 67–85% of COVID-19 patients were admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU), indicated severe ARDS, and the mortality rate in patients with ARDS was up to 61.5% [85]. Additionally, the clinical outcomes in patients with COVID-19 correlated with the severity of ARDS, and the mortality of patients with moderate and severe ARDS was higher than mild ARDS. Furthermore, there is increasing evidence that chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) may be a risk factor for more severe COVID-19 disease. Seven studies showed that COPD patients were also at higher risk of severe COVID-19 compared to patients without COPD (33.4%) [86].

ACE2 plays a significant role in the progression of ARDS. The roles of ACE and ACE2 have been investigated in an animal model of ARDS. They have shown that ACE activity was enhanced in ARDS, whereas ACE2 activity was reduced. This was correlated with enhanced levels of Ang II and reduced levels of Ang-(1–7). Hence, treatment with cAng-(1–7) decreased the severity of lung damage and improved lung function [87]. However, in mice models, ACE2 has been shown to protect animals from severe lung damage, caused by aspiration and sepsis [56]. Based on studies, ACE2 expression in the human airway epithelium was remarkably elevated in COPD patients. Interestingly, smoking status was meaningfully associated with ACE2 gene expression levels in the airway epithelium of COPD patients; for example, current smokers significantly had a higher gene expression than former and never smokers [88].

While the overexpression of the ACE2 may have a protective effect against acute lung injury, the upregulation of ACE2 might predispose patients to an increased risk for infection with the coronavirus, which uses this receptor for entry into target cells. This may partially explain the severity of COVID-19 disease in COPD populations [20]. It is worth noting that the upregulation of ACE2 alone does not support increased susceptibility or severity of the disease. Moreover, relatively low ACE2 expression levels in the bronchial epithelium are associated with more severe lung injury [88, 89].

ACE2 regulation

Evidence suggests that the expression of the ACE2 is regulated by various pathways. Enhanced ACE2 expression can be protective in patients with diabetes, cancer, and cardiovascular disease [90]. Notably, ACE2 protein expression is significantly upregulated under stress conditions, including hypoxic conditions, treatment with IL-1β, and treatment with 5-amino-4-imidazole carboxamideriboside (AICAR). The analysis demonstrated that AICAR and IL-1β treatment upregulates and downregulates ACE2 expression, respectively [90]. The finding showed that cardiac ACE2 is increased following treatment by AT1 receptor blockers (ARBs), nevertheless, Endothelin-1 (ET-1) significantly reduce myocytes ACE2 mRNA levels to downregulate ACE2 activity [91].

ANG II considerably reduces ACE2 activity and downregulates mRNA levels of ACE2 in cardiac myocytes [92]. Another study showed that inhibition of Ang II synthesis altered ACE2 expression in mRNA levels [93]. Evidence suggests that there is a link between Ang II levels and the expression of ACE2 [94]. For example, under hypoxia conditions ACE2 transcription is reduced, on the other hand, hypoxia-induced HIF-1α upregulates ACE expression which in turn leads to higher concentrations of Ang II. Therefore, Ang II mediates the reduction in ACE2 mRNA and its activity [95]. Furthermore, the in vivo experiments have shown that Ang-(1–7) has antagonistic effects on ACE2 expression. In rat models, cardiac and renal ACE2 were decreased in response to Ang-(1–7) infusion [96]. Also, it has been shown that the administration of aldosterone or endothelin-1 significantly reduced myocyte ACE2 mRNA levels [91]. The effects of all trans-retinoic acid on gene and protein expression of ACE2 have been investigated in rats, and a significant upregulation of ACE2 expression in mRNA and protein levels was observed in the heart and kidney [97]. Plasma levels of circulating ACE2 have been reported to be very low or even undetectable in healthy individuals; however, ACE2 levels were significantly increased in the presence of cardiovascular disease. In two distinct cohorts of heart failure patients with COVID-19, men had higher plasma concentrations of ACE2 than women, hence ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers were associated with lower plasma concentrations of ACE2, but mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists were associated with higher concentrations [98].

The sex difference is an important risk factor among COVID-19 patients, compared to women, men, infected with the SARS-CoV-2, experience more severe disease and higher mortality rates [99]. This difference could be derived from increased ACE2 expression in male that plasma levels of ACE2 were higher in males than in females and also this difference could be related to a genetic polymorphism in ACE2 [100]. Previous studies reported that the expression of ACE2 depends on age and sex. As observed in rat lungs, ACE2-expression in females and younger animals is higher than in males and adults. Therefore, it is predictable that higher levels of ACE2 are present in the lungs of children and young people than in adults and old people. Therefore, it can be concluded that there is a direct relationship between the overexpression of ACE2 in children, young people, and women with the lower pathology and morbidity rate of COVID 19. The severity of COVID 19 symptoms can be related to ACE2 genetic polymorphisms that are reported in different populations worldwide [101, 102].

Other studies have shown that aldosterone and estrogens can regulate the expression of ACE2 in cell lines and animal models. In a mouse model of SARS-CoV infection, female mice had lower viral titers and less severe disease and cytokine production; the endogenous estradiol was an important factor in this protection [103]. 17β-estradiol-treated cells expressed lower levels of ACE2 mRNA compared to controls. They showed that sex hormones play critical roles in the regulation of cellular components required for SARS-CoV-2 infectivity and the ability to cause life-threatening disorders [104].

ACE2 targeting for treatment

Recombinant ACE2 (rACE2)

It has been suggested that inhibiting the interaction of SARS-CoV-2 with ACE2 might be used as a therapeutic method in the treatment of patients with COVID-19 [105]. The use of human recombinant soluble ACE2 (hrsACE2) to neutralize the virus and prevent lung damage is now under clinical investigation [106].

Studies have demonstrated that the early stages of SARS-CoV-2 infection can be inhibited by hrsACE2. These data demonstrated that hrsACE2 inhibits SARS-CoV-2 attachment to the host cells. Soluble ACE2 binds to spike protein and reduces binding to ACE2 on the cell membrane and prevents SARS-COV-2 replication (Fig. 4). This inhibitory action of hrsACE2 is dependent on the amount of virus, present in the initial inoculums, and the dose of hrsACE2 [105].

hrsACE2 inhibits SARS COV-2 replication. A SARS-CoV-2 by spike protein directly binds to the ACE2 receptor and then inter to the host cell by endocytosis. B The covering of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein by hrsACE2 lead to the prevention of the interaction between SARS-CoV-2 and ACE2 and subsequently prevents SARS COV-2 replication in the host cell

ACE2 activators

Decrease in pulmonary ACE2 activity is associated with pneumonia; in contrast, its activation can inhibit hyperoxia-induced lung injury by inhibiting the inflammatory response and oxidative stress [107]. Since upregulation of ACE2 has a protective role against severe lung injury, including ARDS and COPD, the development of an ACE2 activator could be a potential therapeutic strategy against COVID-19.

Xanthenone (XNT) or diminazeneaceturate (DIZE) and resorcinolnaphthalein have the ability to activate ACE2 [102]. XNT or DIZE is an anti-parasitic drug for treating trypanosomiasis. In macrophages, DIZE downregulates the MAPK/ERK and STAT phosphorylation (signaling molecules), resulting in the downregulation of IL-6, IL-12, and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) which ultimately reduces inflammatory responses. Treatment with DIZE reduces the expression of CD25 (T cell marker) in spleens of Trypanosoma infected mice, suggesting that DIZE dampens immune system activation [108]. According to experiments, glucocorticoids such as hydrocortisone, prednisolone, methylprednisolone, and dexamethasone showed the strongest effect on activating ACE2 and inhibiting IL-6 [109].

ACE inhibitor and Ang II receptor blocker

High blood pressure in patients with COVID -2019 is one of the symptoms that is associated with worse clinical outcomes. ACE inhibitor (ACEI) and angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB) are widely prescribed for treating high blood pressure [110]. Since commonly used antihypertensive medications may upregulate ACE2 receptors, these concerns have been raised that their use may result in increased morbidity and mortality rate. Lei Fang et al. suggested that patients with cardiac diseases, hypertension, and/or diabetes, who were treated with ACE2 activating drugs, would be at risk for severe COVID-19 infection, because treatment with ACEIs and ARBs may upregulate ACE2 expression [53]. On the contrary, several clinical studies have reported that ACEi/ARB used in COVID-19 patients with hypertension does not worsen COVID-19 disease severity or mortality. Data from clinical studies suggest that ACEI/ARB administration does not increase ACE2 expression and the risk of COVID-19 complications [111, 112]. Other compounds that may increase the expression of the ACE2 receptor include Vitamin C, metformin, resveratrol, vitamin B3, and vitamin D [113].

Conclusion

We summarized the role of ACE2 in the pathogenesis, progression, and treatment of COVID-19 infection. ACE2 controls the metabolism of bradykinin, regulates amino acid transportation, and also modulates insulin secretion. This enzyme is the receptor for the SARS-CoV-2 and has a local protective effect on tissue injury and is implicated in the progression and prognosis of COVID-19. Sex difference is an important risk factor, compared to women; men have more severe disease and higher mortality rates. This difference may be derived from increased ACE2 plasma levels expression in men than in women, while higher tissue expression of this receptor seems to be beneficial for preventing exacerbated inflammatory response during infection. As well as, based on findings, the severity of COVID 19 symptoms can be related to ACE2 genetic polymorphisms in different populations.

Although the global vaccination program seems to be effective in controlling hospitalization rate and deaths, caused by SARS-CoV-2, it is unable to prevent the development of new variants like delta or omicron, which have shown more infectivity or transmissibility. As new variants have relatively reduced vaccine’s potency in increasing neutralizing antibodies, the requisite of ACE2 inhibitory drugs, discussed in this review, becomes more of interest and can be much more effective in curing patients than those which do not target ACE2. Prescribing drugs that may affect ACE2, such as ACEI, ARB, or ACE2 activators and targeting ACE2 by using hrsACE2 can be a potential therapeutic strategy for COVID-19; however, more clinical studies are needed to confirm the effectiveness of these methods.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ACE:

-

Angiotensin-converting enzyme

- ACE 2:

-

Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2

- ACEI:

-

Ace inhibitor

- AICAR:

-

5-Amino-4-imidazole carboxamideriboside

- AKI:

-

Acute kidney injury

- ANG I:

-

Angiotensin I

- ANG II:

-

Angiotensin II

- ARB:

-

Angiotensin II receptor blocker

- ARBS:

-

At1 receptor blockers

- ARDS:

-

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- AT1 R:

-

ACE/AngII/angiotensin receptor 1

- AT1 R:

-

Theace/AngII/angiotensin receptor 1

- COPD:

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus disease 2019

- COVS:

-

Coronaviruses

- DIZE:

-

Diminazeneaceturate

- ET-1:

-

Endothelin-1

- FDA:

-

Food and drug administration

- HRSACE2:

-

Human recombinant soluble ACE2

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- IL:

-

Interleukins

- MERS-COV:

-

Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus

- PD:

-

Protease domain

- RAAS:

-

Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system

- RACE2:

-

Recombinant ACE2

- RBD:

-

Receptor-binding domain

- SARS-COV:

-

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus

- SARS-COV-2:

-

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

- TMPRSS2:

-

Transmembrane protease serine 2

- TNF-α:

-

Tumor necrosis factor

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- XNT:

-

Xanthenone

References

Wu Z, McGoogan JM (2020) Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA 323(13):1239–1242

Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song J, et al. (2020) A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med

Zou L, Ruan F, Huang M, Liang L, Huang H, Hong Z et al (2020) SARS-CoV-2 viral load in upper respiratory specimens of infected patients. N Engl J Med 382(12):1177–1179

Sanders JM, Monogue ML, Jodlowski TZ, Cutrell JB (2020) Pharmacologic treatments for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a review. JAMA 323(18):1824–1836

Perlman S, Netland J (2009) Coronaviruses post-SARS: update on replication and pathogenesis. Nat Rev Microbiol 7(6):439–450

Li F (2016) Structure, function, and evolution of coronavirus spike proteins. Annu Rev Virol 3:237–261

Drexler JF, Gloza-Rausch F, Glende J, Corman VM, Muth D, Goettsche M et al (2010) Genomic characterization of severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus in European bats and classification of coronaviruses based on partial RNA-dependent RNA polymerase gene sequences. J Virol 84(21):11336–11349

Walls AC, Park Y-J, Tortorici MA, Wall A, McGuire AT, Veesler D (2020) Structure, function, and antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein. Cell

Cui J, Li F, Shi Z-L (2019) Origin and evolution of pathogenic coronaviruses. Nat Rev Microbiol 17(3):181–192

Lukassen S, Chua RL, Trefzer T, Kahn NC, Schneider MA, Muley T et al (2020) SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE 2 and TMPRSS 2 are primarily expressed in bronchial transient secretory cells. EMBO J 39(10):e105114

Hassanzadeh K, Perez Pena H, Dragotto J, Buccarello L, Iorio F, Pieraccini S et al (2020) Considerations around the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein with particular attention to COVID-19 brain infection and neurological symptoms. ACS Chem Neurosci 11(15):2361–2369

Liu J, Zheng X, Tong Q, Li W, Wang B, Sutter K et al (2020) Overlapping and discrete aspects of the pathology and pathogenesis of the emerging human pathogenic coronaviruses SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, and 2019-nCoV. J Med Virol 92(5):491–494

Read MC (2020) EID: high contagiousness and rapid spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. Emerg Infect Dis 26

Chu H, Chan JF-W, Wang Y, Yuen TT-T, Chai Y, Hou Y, et al. (2020) Comparative replication and immune activation profiles of SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV in human lungs: an ex vivo study with implications for the pathogenesis of COVID-19. Clin Infect Dis

Shang J, Wan Y, Luo C, Ye G, Geng Q, Auerbach A et al (2020) Cell entry mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2. Proc Natl Acad Sci 117(21):11727–11734

Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y et al (2020) Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan. China The lancet 395(10223):497–506

Guan W-j, Ni Z-y, Hu Y, Liang W-h, Ou C-q, He J-x et al (2020) Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med 382(18):1708–1720

Xu Z, Shi L, Wang Y, Zhang J, Huang L, Zhang C et al (2020) Pathological findings of COVID-19 associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet Respir Med 8(4):420–422

Kai H, Kai M (2020) Interactions of coronaviruses with ACE2, angiotensin II, and RAS inhibitors—lessons from available evidence and insights into COVID-19. Hypertension Res 1–7

Leung JM, Yang CX, Tam A, Shaipanich T, Hackett T-L, Singhera GK, et al. (2020) ACE-2 expression in the small airway epithelia of smokers and COPD patients: implications for COVID-19. Eur Respir J 55(5)

Dalan R, Bornstein SR, El-Armouche A, Rodionov RN, Markov A, Wielockx B et al (2020) The ACE-2 in COVID-19: Foe or friend? Horm Metab Res 52(5):257

Zhou Q, Yan R, Zhang Y, Li Y, Xia L (2020) Structure of dimeric full-length human ACE2 in complex with B0AT1. BioRxiv

Bourgonje AR, Abdulle AE, Timens W, Hillebrands JL, Navis GJ, Gordijn SJ, et al. (2020) Angiotensin‐converting enzyme‐2 (ACE2), SARS‐CoV‐2 and pathophysiology of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19). J Pathol

Xiao L, Sakagami H, Miwa N (2020) ACE2: the key molecule for understanding the pathophysiology of severe and critical conditions of COVID-19: Demon or angel? Viruses 12(5):491

Deb P, Molla M, Ahmed M, Saif-Ur-Rahman K, Das MC, Das D (2021) A review of epidemiology, clinical features and disease course, transmission dynamics, and neutralization efficacy of SARS-CoV-2 variants. Egypt J Bronchol 15(1):1–14

Ferré VM, Peiffer-Smadja N, Visseaux B, Descamps D, Ghosn J, Charpentier C (2022) Omicron SARS-CoV-2 variant: what we know and what we don’t. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med 41(1):100998

Tao K, Tzou PL, Nouhin J, Gupta RK, de Oliveira T, Kosakovsky Pond SL et al (2021) The biological and clinical significance of emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants. Nat Rev Genet 22(12):757–773

Tregoning JS, Flight KE, Higham SL, Wang Z, Pierce BF (2021) Progress of the COVID-19 vaccine effort: viruses, vaccines and variants versus efficacy, effectiveness and escape. Nat Rev Immunol 21(10):626–636

Shereen MA, Khan S, Kazmi A, Bashir N, Siddique R (2020) COVID-19 infection: origin, transmission, and characteristics of human coronaviruses. J Adv Res

Zhang X, Li S, Niu S (2020) ACE2 and COVID-19 and the resulting ARDS. Postgrad Med J

Wu A, Peng Y, Huang B, Ding X, Wang X, Niu P, et al. (2020) Genome composition and divergence of the novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) originating in China. Cell Host Microbe

Muniyappa R, Gubbi S (2020) COVID-19 pandemic, coronaviruses, and diabetes mellitus. Am J Physiol-Endocrinol Metab 318(5):E736–E741

Li F (2015) Receptor recognition mechanisms of coronaviruses: a decade of structural studies. J Virol 89(4):1954–1964

Saha P, Banerjee AK, Tripathi PP, Srivastava AK, Ray U (2020) A virus that has gone viral: amino acid mutation in S protein of Indian isolate of Coronavirus COVID-19 might impact receptor binding, and thus, infectivity. Biosci Rep 40(5)

Lan J, Ge J, Yu J, Shan S, Zhou H, Fan S et al (2020) Structure of the SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor-binding domain bound to the ACE2 receptor. Nature 581(7807):215–220

Ou X, Liu Y, Lei X, Li P, Mi D, Ren L et al (2020) Characterization of spike glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2 on virus entry and its immune cross-reactivity with SARS-CoV. Nat Commun 11(1):1–12

Shang J, Ye G, Shi K, Wan Y, Luo C, Aihara H et al (2020) Structural basis of receptor recognition by SARS-CoV-2. Nature 581(7807):221–224

Tai W, He L, Zhang X, Pu J, Voronin D, Jiang S et al (2020) Characterization of the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of 2019 novel coronavirus: implication for development of RBD protein as a viral attachment inhibitor and vaccine. Cell Mol Immunol 17(6):613–620

Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder S, Krüger N, Herrler T, Erichsen S, et al. (2020) SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell

Yang G (2020). H2S as a potential defence against COVID-19? Am J Physiol-Cell Physiol

Zhang H, Penninger JM, Li Y, Zhong N, Slutsky AS (2020) Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) as a SARS-CoV-2 receptor: molecular mechanisms and potential therapeutic target. Intensive Care Med 46(4):586–590

Donoghue M, Hsieh F, Baronas E, Godbout K, Gosselin M, Stagliano N et al (2000) A novel angiotensin-converting enzyme–related carboxypeptidase (ACE2) converts angiotensin I to angiotensin 1–9. Circ Res 87(5):e1–e9

Rice GI, Thomas DA, Grant PJ, Turner AJ, Hooper NM (2004) Evaluation of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE), its homologue ACE2 and neprilysin in angiotensin peptide metabolism. Biochem J 383(1):45–51

Tipnis SR, Hooper NM, Hyde R, Karran E, Christie G, Turner AJ (2000) A human homolog of angiotensin-converting enzyme cloning and functional expression as a captopril-insensitive carboxypeptidase. J Biol Chem 275(43):33238–33243

Gheblawi M, Wang K, Viveiros A, Nguyen Q, Zhong J-C, Turner AJ et al (2020) Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2: SARS-CoV-2 receptor and regulator of the renin-angiotensin system: celebrating the 20th anniversary of the discovery of ACE2. Circ Res 126(10):1456–1474

Chamsi-Pasha MA, Shao Z, Tang WW (2014) Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 as a therapeutic target for heart failure. Curr Heart Fail Rep 11(1):58–63

Klhůfek J (2020) The role of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 in the pathogenesis of COVID-19: The villain or the hero? Acta Clinica Belgica 1–8

Li XC, Zhang J, Zhuo JL (2017) The vasoprotective axes of the renin-angiotensin system: physiological relevance and therapeutic implications in cardiovascular, hypertensive and kidney diseases. Pharmacol Res 125:21–38

Putnam K, Shoemaker R, Yiannikouris F, Cassis LA (2012) The renin-angiotensin system: a target of and contributor to dyslipidemias, altered glucose homeostasis, and hypertension of the metabolic syndrome. Am J Physiol-Heart Circ Physiol 302(6):H1219–H1230

Walters TE, Kalman JM, Patel SK, Mearns M, Velkoska E, Burrell LM (2017) Angiotensin converting enzyme 2 activity and human atrial fibrillation: increased plasma angiotensin converting enzyme 2 activity is associated with atrial fibrillation and more advanced left atrial structural remodelling. Ep Europace 19(8):1280–1287

Patel SK, Velkoska E, Burrell LM (2013) Emerging markers in cardiovascular disease: Where does angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 fit in? Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 40(8):551–559

Li Y, Zhou W, Yang L, You R (2020) Physiological and pathological regulation of ACE2, the SARS-CoV-2 receptor. Pharmacol Res 104833

Fang L, Karakiulakis G, Roth M (2020) Are patients with hypertension and diabetes mellitus at increased risk for COVID-19 infection? Lancet Respir Med 8(4):e21

Kuba K, Imai Y, Ohto-Nakanishi T, Penninger JM (2010) Trilogy of ACE2: a peptidase in the renin–angiotensin system, a SARS receptor, and a partner for amino acid transporters. Pharmacol Ther 128(1):119–128

Bosch BJ, Smits SL, Haagmans BL (2014) Membrane ectopeptidases targeted by human coronaviruses. Curr Opin Virol 6:55–60

Imai Y, Kuba K, Rao S, Huan Y, Guo F, Guan B et al (2005) Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 protects from severe acute lung failure. Nature 436(7047):112–116

Fu J, Zhou B, Zhang L, Balaji KS, Wei C, Liu X, et al. (2020) Expressions and significances of the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 gene, the receptor of SARS-CoV-2 for COVID-19. Mol Biol Rep 1–10

Xu H, Zhong L, Deng J, Peng J, Dan H, Zeng X et al (2020) High expression of ACE2 receptor of 2019-nCoV on the epithelial cells of oral mucosa. Int J Oral Sci 12(1):1–5

Hamming I, Timens W, Bulthuis M, Lely A, Navis G, van Goor H (2004) Tissue distribution of ACE2 protein, the functional receptor for SARS coronavirus. A first step in understanding SARS pathogenesis. J Pathol J Pathol Soc Great Br Ireland 203(2):631–637

To K, Lo AW (2004) Exploring the pathogenesis of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS): the tissue distribution of the coronavirus (SARS-CoV) and its putative receptor, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2). J Pathol J Pathol Soc Great Br Ireland 203(3):740–743

Gan R, Rosoman NP, Henshaw DJ, Noble EP, Georgius P, Sommerfeld N (2020) COVID-19 as a viral functional ACE2 deficiency disorder with ACE2 related multi-organ disease. Med Hypotheses 144:110024

Gavriatopoulou M, Korompoki E, Fotiou D, Ntanasis-Stathopoulos I, Psaltopoulou T, Kastritis E, et al. (2020) Organ-specific manifestations of COVID-19 infection. Clin Exp Med 1–14

Ottestad W, Seim M, Mæhlen JO. COVID-19 with silent hypoxemia. Tidsskrift for Den norske legeforening. 2020.

Mason RJ (2020) Pathogenesis of COVID-19 from a cell biology perspective. Eur Respiratory Soc

Lai C-C, Shih T-P, Ko W-C, Tang H-J, Hsueh P-R (2020) Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and corona virus disease-2019 (COVID-19): the epidemic and the challenges. Int J Antimicrob Agents 105924

Ragab D, Salah Eldin H, Taeimah M, Khattab R, Salem R (2020) The COVID-19 cytokine storm; what we know so far. Front Immunol 11:1446

Ye Q, Wang B, Mao J (2020) The pathogenesis and treatment of theCytokine Storm’in COVID-19. J Infect 80(6):607–613

Qin C, Zhou L, Hu Z, Zhang S, Yang S, Tao Y, et al. (2020) Dysregulation of immune response in patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. Clin Infect Dis

Pan L, Mu M, Yang P, Sun Y, Wang R, Yan J, et al. Clinical characteristics of COVID-19 patients with digestive symptoms in Hubei, China: a descriptive, cross-sectional, multicenter study. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2020;115.

Chen L, Lou J, Bai Y, Wang M. (2020) COVID-19 disease with positive fecal and negative pharyngeal and sputum viral tests. Am J Gastroenterol 115

Guo T, Fan Y, Chen M, Wu X, Zhang L, He T, et al. (2020) Cardiovascular implications of fatal outcomes of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Cardiol

Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, Zhu F, Liu X, Zhang J et al (2020) Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA 323(11):1061–1069

Yang X, Yu Y, Xu J, Shu H, Liu H, Wu Y, et al. (2020) Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir Med

Cheng Y, Luo R, Wang K, Zhang M, Wang Z, Dong L, et al. (2020) Kidney disease is associated with in-hospital death of patients with COVID-19. Kidney Int

Galván Casas C, Catala A, Carretero Hernández G, Rodríguez-Jiménez P, Fernández-Nieto D, Rodríguez-Villa Lario A et al (2020) Classification of the cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19: a rapid prospective nationwide consensus study in Spain with 375 cases. Br J Dermatol 183(1):71–77

Fernandez-Nieto D, Jimenez-Cauhe J, Suarez-Valle A, Moreno-Arrones OM, Saceda-Corralo D, Arana-Raja A et al (2020) Characterization of acute acral skin lesions in nonhospitalized patients: a case series of 132 patients during the COVID-19 outbreak. J Am Acad Dermatol 83(1):e61–e63

Mao L, Wang M, Chen S, He Q, Chang J, Hong C, et al. (2020) Neurological manifestations of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective case series study

Wu P, Duan F, Luo C, Liu Q, Qu X, Liang L et al (2020) Characteristics of ocular findings of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Hubei Province, China. JAMA Ophthalmol 138(5):575–578

Öncül H, Öncül FY, Alakus MF, Çağlayan M, Dag U (2020) Ocular findings in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) in an outbreak hospital. Journal of medical virology

Terpos E, Ntanasis‐Stathopoulos I, Elalamy I, Kastritis E, Sergentanis TN, Politou M, et al. (2020) Hematological findings and complications of COVID‐19. American journal of hematology

Li T, Lu H, Zhang W (2020) Clinical observation and management of COVID-19 patients. Emerg Microbes Infect 9(1):687–690

Tan T, Khoo B, Mills EG, Phylactou M, Patel B, Eng PC et al (2020) Association between high serum total cortisol concentrations and mortality from COVID-19. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 8(8):659–660

Ferguson ND, Fan E, Camporota L, Antonelli M, Anzueto A, Beale R et al (2012) The Berlin definition of ARDS: an expanded rationale, justification, and supplementary material. Intensive Care Med 38(10):1573–1582

Matthay MA, Zemans RL (2011) The acute respiratory distress syndrome: pathogenesis and treatment. Annu Rev Pathol 6:147–163

Xiao K, Hou F, Huang X, Li B, Qian ZR, Xie L (2020) Mesenchymal stem cells: current clinical progress in ARDS and COVID-19. Stem Cell Res Ther 11(1):1–7

Alqahtani JS, Oyelade T, Aldhahir AM, Alghamdi SM, Almehmadi M, Alqahtani AS et al (2020) Prevalence, severity and mortality associated with COPD and smoking in patients with COVID-19: a rapid systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 15(5):e0233147

Wösten-van Asperen RM, Lutter R, Specht PA, Moll GN, van Woensel JB, van der Loos CM et al (2011) Acute respiratory distress syndrome leads to reduced ratio of ACE/ACE2 activities and is prevented by angiotensin-(1–7) or an angiotensin II receptor antagonist. J Pathol 225(4):618–627

Leung JM, Niikura M, Yang CWT, Sin DD (2020) COVID-19 and COPD. Eur Respiratory Soc

Sungnak W, Huang N, Bécavin C, Berg M, Queen R, Litvinukova M et al (2020) SARS-CoV-2 entry factors are highly expressed in nasal epithelial cells together with innate immune genes. Nat Med 26(5):681–687

Clarke NE, Belyaev ND, Lambert DW, Turner AJ (2014) Epigenetic regulation of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) by SIRT1 under conditions of cell energy stress. Clin Sci 126(7):507–516

Gallagher PE, Ferrario CM, Tallant EA (2008) Regulation of ACE2 in cardiac myocytes and fibroblasts. Am J Physiol-Heart Circ Physiol 295(6):H2373–H2379

Razeghian-Jahromi I, Zibaeenezhad MJ, Lu Z, Zahra E, Mahboobeh R, Lionetti V (2020) Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2: a double-edged sword in COVID-19 patients with an increased risk of heart failure. Heart Fail Rev 1–10

Iyer SN, Chappell MC, Averill DB, Diz DI, Ferrario CM (1998) Vasodepressor actions of angiotensin-(1–7) unmasked during combined treatment with lisinopril and losartan. Hypertension 31(2):699–705

Ferreira AJ, Santos RA, Raizada MK (2012) Angiotensin-(1–7)/angiotensin-converting enzyme 2/mas receptor axis and related mechanisms. Int J Hypertens 2012

Zhang R, Wu Y, Zhao M, Liu C, Zhou L, Shen S et al (2009) Role of HIF-1α in the regulation ACE and ACE2 expression in hypoxic human pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol-Lung Cell Mol Physiol 297(4):L631–L640

Tan Z, Wu J, Ma H (2011) Regulation of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 and Mas receptor by Ang-(1–7) in heart and kidney of spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone Syst 12(4):413–419

Zhong J-C, Huang D-Y, Yang Y-M, Li Y-F, Liu G-F, Song X-H et al (2004) Upregulation of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 by all-trans retinoic acid in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension 44(6):907–912

Sama IE, Ravera A, Santema BT, van Goor H, Ter Maaten JM, Cleland JG et al (2020) Circulating plasma concentrations of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 in men and women with heart failure and effects of renin–angiotensin–aldosterone inhibitors. Eur Heart J 41(19):1810–1817

Sharma G, Volgman AS, Michos ED (2020) Sex differences in mortality from COVID-19 pandemic: Are men vulnerable and women protected? JACC Case Rep 2(9):1407–1410

Patel S, Rauf A, Khan H, Abu-Izneid T (2017) Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone (RAAS): The ubiquitous system for homeostasis and pathologies. Biomed Pharmacother 94:317–325

Hussain M, Jabeen N, Raza F, Shabbir S, Baig AA, Amanullah A, et al. (2020) Structural variations in human ACE2 may influence its binding with SARS‐CoV‐2 spike protein. J Med Virol

Puertas RR (2020) ACE2 activators for the treatment of COVID 19 patients. J Med Virol

Klein SL, Dhakal S, Ursin RL, Deshpande S, Sandberg K, Mauvais-Jarvis F (2020) Biological sex impacts COVID-19 outcomes. PLoS Pathog 16(6):e1008570

Stelzig KE, Canepa-Escaro F, Schiliro M, Berdnikovs S, Prakash Y, Chiarella SE (2020) Estrogen regulates the expression of SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2 in differentiated airway epithelial cells. Am J Physiol-Lung Cell Mol Physiol

Monteil V, Kwon H, Prado P, Hagelkrüys A, Wimmer RA, Stahl M, et al. (2020) Inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 infections in engineered human tissues using clinical-grade soluble human ACE2. Cell

Zhang N, Li C, Hu Y, Li K, Liang J, Wang L, et al. (2020) Current development of COVID-19 diagnostics, vaccines and therapeutics. Microbes Infect

Fang Y, Gao F, Liu Z (2019) Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 attenuates inflammatory response and oxidative stress in hyperoxic lung injury by regulating NF-κB and Nrf2 pathways. QJM Int J Med 112(12):914–924

Qaradakhi T, Gadanec LK, McSweeney KR, Tacey A, Apostolopoulos V, Levinger I et al (2020) The potential actions of angiotensin-converting enzyme II (ACE2) activator diminazene aceturate (DIZE) in various diseases. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 47(5):751–758

Xiang Z, Liu J, Shi D, Chen W, Li J, Yan R et al (2020) Glucocorticoids improve severe or critical COVID-19 by activating ACE2 and reducing IL-6 levels. Int J Biol Sci 16(13):2382

Yamamoto K, Mano T, Yoshida J, Sakata Y, Nishikawa N, Nishio M et al (2005) ACE inhibitor and angiotensin II type 1 receptor blocker differently regulate ventricular fibrosis in hypertensive diastolic heart failure. J Hypertens 23(2):393–400

Lam KW, Chow KW, Vo J, Hou W, Li H, Richman PS et al (2020) Continued in-hospital angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor and angiotensin II receptor blocker use in hypertensive COVID-19 patients is associated with positive clinical outcome. J Infect Dis 222(8):1256–1264

Sriram K, Insel PA (2020) Risks of ACE inhibitor and ARB usage in COVID‐19: evaluating the evidence. Clin Pharmacol Therap

McLachlan CS (2020) The angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor in the prevention and treatment of COVID-19 are distinctly different paradigms. Clin Hypertens 26(1):1–3

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Searching and data collection were performed by AB and AP. The first-original draft of the manuscript was written by AB, AP, AB, and NR and edited by AB and SSM. The figures were prepared by AB. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pouremamali, A., Babaei, A., Malekshahi, S.S. et al. Understanding the pivotal roles of ACE2 in SARS-CoV-2 infection: from structure/function to therapeutic implication. Egypt J Med Hum Genet 23, 103 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43042-022-00314-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43042-022-00314-9