Abstract

This study was designed to evaluate the bioactivities such as β-glucosidase activity, α-galactosidase activity, and the growth behavior of the Lactobacillus cultures in soy milk medium. Ten Lactobacillus cultures were considered in this study. L. fermentum (M2) and L. casei (NK9) were selected due to their better α-galactosidase, β-glucosidase activity and growth behavior in soy milk medium during fermentation. Further, soy milk fermented with M2 showed higher proteolytic activity (0.67 OD) and ACE-inhibitory (48.44%) than NK9 (proteolytic activity: 0.48 OD and ACE-inhibitory activity: 41.33%). Bioactive peptides produced during the fermentation of soy milk using the selected Lactobacillus cultures were also identified with potent ACE-inhibitory activity by MALDI-TOF spectrometry, and the identified ACE inhibitory peptide sequences from fermented soy milk were characterized using Biopep database.

Graphical abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Soy milk is a most ideal choice of milk for individuals with problems of lactose intolerance and faith in vegan (Wang 2002). Soy milk has a similar composition to bovine milk. Fermentation of soy milk is the best strategy for enhancing the organoleptic and nutritional attributes of soy milk (Wang 2002). Fermentation of soy milk also improves the flavor and texture of soy curd, which makes it more acceptable to the consumers. Fermented soy milk also produces novel soy biomolecules with health-beneficial properties (Akabanda et al. 2010). Soy yogurt was prepared using commercial soy milk with L. casei, Bifidobacterium, L. acidophilus (Donkor et al. 2005). During fermentation, the organoleptic properties and physicochemical properties of soy milk are improved because of the lactic cultures, which produce the enzymes like β-glucosidase and α-galactosidase. The soy oligosaccharides such as sucrose, raffinose, and stachyose get hydrolysed by α-galactosidase enzyme of the lactic cultures and cause a decrease in its beany flavor and flatulence. Fermentation of soy milk is likewise the best strategy that produces different biomolecules like isoflavones and bioactive peptides with significant bio-functional properties (Kulkarni et al. 2006; Singh et al. 2014; Hati et al. 2015a; Singh et al. 2017). Numerous researches have been done on fermentation of soy milk utilizing single lactic culture or blended cultures including Lactobacillus plantarum, L. cellobiose, L. delbrueckii, L. fermentum, L. pentosaceus, L. bulgaricus and L. fermenti in order to reduce the oligosaccharides contents (stachyose and raffinose) that cause flatulence (Wang 2002). An investigation was conducted to evaluate the β-glucosidase activity and isoflavone bioconversion to aglycones in fermented soy milk with the Lactobacillus cultures namely L. rhamnosus C2, L. rhamnosus C6, L. rhamnosus NCDC24, L. rhamnosus NCDC19 and L. casei NCDC297. After incubation, samples of L. rhamnosus C6 culture at 37 °C for 12 h produced the highest β-glucosidase and isoflavone aglycones. Isoflavone aglycone amount in fermented soy milk is enhancing the nutritional properties of soy milk (Hati et al. 2014). Apart from isoflavones, the generation of bioactive peptides from fermented soy milk is also important for showing the health benefits. These bioactive peptides can be created by proteolytic enzymes, microbial fermentation, or food processing.

However, the best strategy for production of peptides in food systems is fermentation by food-grade microorganisms (Singh et al. 2014). Di-peptides, oligopeptides, and tri-peptides, due to the proteolytic activity of lactic acid bacteria (LAB), are being released from fermented soy milk. Microbial fermentation is the least costly strategy in terms of enzymatic hydrolysis compared with the different techniques for the generation of bioactive peptides. Proteases releasing microbes are the least costly cell factories and are therefore perceived as healthy for use (GRAS [Generally recognized as safe] status) (Agyei and Danquah 2011).

From miso and doenjang, the release of bioactive peptides with angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitory activity was reported. Tri-peptides (Val-Pro-Pro and Ile-Pro-Pro) were produced from casein molecule of miso paste, exhibited antihypertensive activity in spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR) (Inoue et al. 2009). Probiotic microorganisms with the capability of producing ACE-inhibitor peptides is an added advantage for use in the fermentation process. Proteolytic activity of probiotics in soy milk or soy yogurt was reported to liberate peptides with ACE-inhibitory attributes (Tsai et al. 2006). In the study, potential LAB was evaluated for α-galactosidase, β-glucosidase, proteolytic, ACE-inhibitory activities, and the production of peptides during fermentation of soy milk.

Materials and methods

Materials

In this study, soybean (AAU NRC-37- variety) was procured from Hill Millet Research Station of Anand Agricultural University, Gujarat, India.

Standard cultures

Ten lactic cultures viz. L. fermentum (M2), L. fermentum (M3), L. fermentum (M4), L. helveticus MTCC 5463 (V3), L. casei (NK9), L. rhamnosus (M8), L. rhamnosus (M9), L. paracasei (M11), L. plantarum (M38) and L. paracasei (M16) were used in this study. All the cultures were procured from Dairy Culture Collection, Department of Dairy Microbiology, Sheth MC College of Dairy Science, AAU, Anand, India. The lactic acid bacteria were maintained by propagating through sub-culturing in reconstituted skim milk (11% total solids). During activation of the lactic cultures, the rate of inoculation was 1% (v/v) at 37 °C for 24 h.

Soy milk preparation

Soy milk was prepared according to the procedure followed by Hati et al. (2015a). One hundred grams soybeans were taken in 2 L beaker and further soaked for 14–16 h in 1 L distilled water at room temperature (28 °C). Then after draining off the soaked water, blanching was carried out in stainless steel steam jacket kettle containing double distilled water at 98 °C for 15–20 min. The quantity of water taken was three times the weight of the original soy beans. After thorough washing, testa was removed and further hulls were separated. Soy slurry was papered using the blender (Philips, India) by adding six times boiled distilled water. During blending, the inactivation of lipoxygenase enzyme was occurred due to boiled water. Finally, the slurry was filtered through double-layered muslin cloth to remove undesirable hulls. Sterilization of soy milk was carried out at 121 °C at 15 psi for 20 min. Finally, 500 mL soy milk was prepared from 100 g soybeans.

Screening of Lactobacillus cultures on the basis of α-galactosidase activity

All the Lactobacillus cultures were evaluated for α-galactosidase activity. Further, the best two lactic cultures with the highest α-galactosidase activity were selected.

Sample preparation

All the lactic cultures were activated in sterile soy milk. Lactic cultures were inoculated in sterile soy milk at 2% (v/v) of inoculation rate and further incubated at different time intervals, i.e., 0 h, 6 h, 12 h, 18 h & 24 h at 37 °C.

Crude α-galactosidase extraction

α-galactosidase activity plays a crucial role in the good growth of lactic cultures in the soy-based medium, free from lactose. The lactic cultures were tested for α-galactosidase activity in soy milk by following the procedure of Tsangalis et al. (2004) and Scalabrini et al. (1998). After different time of intervals (0 h, 6 h, 12 h, 18 h & 24 h at 37 °C), an aliquot of 50 mL was taken out aseptically from each sample and stored at 4 °C. Centrifugation was carried out to harvest the bacterial cells. All the samples were centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C in the refrigerated centrifuge. Cell pellets were washed by using 20 mL of cold 50 mM sodium citrate buffer (pH 5.5) and further centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 10 min, and this step was repeated twice. Further, the samples were sonicated by dissolving cell pellets in 10 mL sodium citrate buffer. After sonication, cell debris were discarded and supernatant was used as a crude enzyme for further study after centrifugation.

Determination of α-galactosidase activity

α-galactosidase activity of all the samples was analyzed by the following method of Hati et al. (2014). Five hundred microliter of 5 mM p-nitrophenyl-α-D galactopyranoside (pNPG) was mixed with 250 μL of crude enzyme extract and further incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. Then the reaction was terminated by adding 500 μL of cold 0.2 M sodium carbonate to the mixture. Based on the rate of hydrolysis of pNPG, α-galactosidase activity was determined. Release of total amount p-nitrophenol was measured by using spectrophotometer (Systronics PC based double beam spectrophotometer 2202, India) at 410 nm. One unit of enzyme activity was defined as the amount of enzyme that released 1 μmol of p-nitrophenol from pNPG per milliliter per min under assay conditions (Hati et al. 2014).

Determination of β-glucosidase activity

β-glucosidase activity of lactic cultures helps in the biotransformation of soy isoflavones into bioactive aglycones. Thus, all the Lactobacillus cultures were also screened on the basis of β-glucosidase activity.

Sample preparation

All the lactic cultures were activated in sterile soy milk medium. Two successive transfers were given to all the lactic cultures in soy milk medium, for improving their adaptability in soy milk medium (Nelson et al. 1976). Lactic cultures were inoculated in sterile soy milk at 2% (v/v) of inoculation rate and further incubated at different time intervals, i.e., 0 h, 6 h, 12 h, 18 h & 24 h at 37 °C.

Determination of β-glucosidase activity

The lactic cultures were evaluated for the presence of β-glucosidase activity by determining the rate of hydrolysis of p-nitrophenol β-D-glucopyranoside (pNPG) (HiMedia, India) as reported by Otieno et al. (2006) and Scalabrini et al. (1998) with some modifications. All the cultures were inoculated with 2% (v/v) rate of inoculation and incubated at different time intervals, i.e., 0 h, 6 h, 12 h, 18 h & 24 h at 37 °C. During the process of fermentation, an aliquot sample of 50 mL was withdrawn after every 6 h of incubations, i.e., 0 h, 6 h, 12 h, 18 h & 24 h and stored at 4 °C. Further, centrifugation was carried out to recover the supernatant solution. For enzymatic activity, 5 mM pNPG (substrate) was taken as a substrate for the activity. Five hundred microliter substrate and 5 mL supernatant solution from each sample were mixed together and further incubated for 30 min at 37 °C. Enzymatic reaction was terminated by adding 250 μL cold 0.2 M sodium carbonate. Further, the mixture was centrifuged at 15000 rpm for 30 min using a centrifuge (Eppendrorf, US), and impurities was filtered using a syringe filter (0.45 μm; Milllipore, USA). Finally, the amount of release of p-nitrophenol was taken as an indicator of the targeted activity and further estimated by measuring absorbance at 410 nm through a spectrophotometer (Systronics UV VIS double beam Spectrophotometer, India). One unit of the enzyme activity is defined as the quantity of β-glucosidase action that released one nanomole of p-nitrophenol from pNPG per milliliter per min at 37 °C under the assay conditions (Hati et al. 2014).

Evaluation of the growth behavior of lactic cultures in soy milk

All the cultures were aseptically inoculated in the sterile 100 mL soy milk medium, inoculated with 2% rate (v/v) for 24 h at 37 °C. Further, 2 mL sample was taken and inoculated in each 100 mL soy milk, which were incubated for 0 h, 3 h, 6 h, 9 h, 12 h, 15 h & 18 h at 37 °C. Further, each sample was tested for pH, titratable acidity & lactic counts.

pH

The pH of fermented soy milk samples was measured using a digital pH meter (OAKTON pH 700, India). Ten milliliter well mixed fermented soy milk sample was put into a beaker and then pH was measured by immersing the pH electrode into the soy milk samples. Standard buffer solutions of pH 4, 7 and 9 were used to calibrate the pH meter before analysis FSSAI (2015).

Titratable acidity

The titratable acidity of fermented soy milk samples was estimated following the method of Ranganna (2012). Along with the same amount of distilled water, a 10 mL sample was taken and titrated using 0.1 [M] NaOH with 0.5 mL phenolphthaleinine (indicator). Titration was continued till the the colour reach to faint pink.

where, mL = 0.1 [N] NaOH used, N = Normality of 0.1 N NaOH, V = mL sample used.

Determination of Lactobacillus counts

Determination of Lactobacillus counts of fermented soy milk samples was carried out following the method prescribed by Downes and Ito (2001). One milliliter sample was diluted with 9 mL physiological saline solution (V/V) to assess viable cell counts, and then serial dilutions were prepared at a ratio of 1:10. One milliliter aliquot of various samples was used to calculate the overall viable lactobacilli count per mL of particular growth media [deMan, Rogosa and Sharpe (MRS) media, HiMedia, India]. The viable cell counts were expressed in log CFU/mL (Abraham et al., 2014).

Assessment of proteolytic activity

Procedures suggested by Hati et al. (2015b) and Solanki et al. (2017) were used for the determination of proteolytic activity using the OPA (O-phthalaldehyde) method. 2.5 mL cultures were added to 5 mL 0.75% trichloroacetic acid and the mixture was filtered using Whatman filter paper 42 (MFS. Inc., CA, USA). One hundred fifty microliter filtrate was added to 3 mL OPA (O-phthalaldehyde) reagent, and the absorbance of the solution was estimated spectrophotometrically at 340 nm after 2 min at room temperature. The proteolytic activity of these bacterial cultures was expressed as the free amino groups measured at 340 nm.

Determination of ACE inhibitory activity

The ACE-inhibitory activity of the fermented samples was determined by the method of Cushman and Cheung (1971). Here, HHL (Hippuryl-L-histidyl-L-leucine) has used a substrate and supernatant of samples was used as a sample. The ACE enzyme was used as an initiator, and HCL was used as a terminator of the enzymatic reaction. Liberated hippuric acid was extracted using ethyl acetate, and absorbance was measured by following the method of Cushman and Cheung (1971). Deionized water was mixed residues of hippuric acid, and further absorbance was measured at 250 nm using a spectrophotometer (Systronic Double beam Spectrophotometer 2202, India). All Blank solution and control solution for the activity were prepared using the method prescribed by Hati et al. (2015b).

MALDI TOF (matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time of flight) based peptide analysis

The peptide solution obtained after trypsinization was mixed with a matrix solution of α-cyano-4-hydroxycynnamic acid (HCCA) solution in a 1:1 ratio, and the resulting 2 μL was spotted onto the MALDI plate. The laser pulse duration was 1–5 ns (ns), and the laser frequency was 100 Hz. After air-drying the sample, it was analyzed on the MALDI TOF/TOF ultraflex III instrument, and further analysis was done with ultraflex analysis software for obtaining the peptide mass fingerprint. The masses obtained in the peptide mass fingerprint were submitted for Mascot search in the concerned database for identification of the protein. For Protein Identification, MASCOT was found to be the most suitable database search engine. The peptides which were identified using MASCOT were then matched with BIOPEP database (Wang et al. 2013).

Results and discussion

Screening of Lactobacillus cultures on the basis of α-galactosidase activity

In the study, ten Lactobacillus cultures were considered and selected for the ability to release α-galactosidase. The enzymatic ability depends on the reaction of α-galactosidase with pNPG as substrate, and it produces p-nitrophenol in the medium with yellow color due to release of p-nitrophenol from the substrate (Table 1). In this study, all the cultures exhibited a different ability for the production of α-galactosidase during fermentation. This was in concurrence with the report of Scalabrini et al. (1998), who found that the fermented soy milk showed different degrees of α-galactosidase activity relying upon the various starter cultures.

From Table 1, it was found that α-galactosidase action was contrasting fundamentally (P < 0.05) with incubation times. Likewise, there was a significant difference (P < 0.05) noticed within the cultures. It was observed that the α-galactosidase activity of ten Lactobacillus cultures was significantly increased with the time of incubation. In this experiment, all the cultures produced α-galactosidase in the range of 6.98 U/mg to 13.90 U/mg after 24 h of incubation at 37 °C. NK9 (L. casei) culture was showing highest activity (13.90 U/mg) followed by M2 (L. fermentum) (12.94 U/mg), then V3 (L. helveticus) (12.10 U/mg) and M8 (11.74 U/mg). These observations were in agreement with the work reported by Mital and Steinkraus (1975). They used a strain of L. fermentum NRRL B-585, which showed the α-galactosidase activity (Table 2). Some other researchers reported that the highest enzyme activity was exhibited by K4 (L. rhamnosus) as 0.407 enzyme units, followed by K3 (L. fermentum) with 0.399 enzyme units and then K16 (L. fermentum) with 0.357 enzyme units (μM/mL) than other cultures in soy milk which supported our findings (Mishra et al. 2017). Lactic culture, C6 (L. rhamnosus) has shown highest α-galactosidase activity (1.99 U/mg), followed by L. rhamnosus NCDC 19 (1.38 U/mg), L. casei NCDC 299 (0.68 U/mg) and L. rhamnosus C2 (0.66 U/mg) (Hati 2012). L. plantarum LR C6 has shown the highest activity (17.39 ± 0.64 U/mL) after the incubation of 24 h, which was significantly higher (P < 0.05) in comparison to reference NCDC 288 (L. helveticus) strain as well as other lactobacilli (Singh and Vij 2018). Furthermore, LR C25 (L. rhamnosus) showed 16.6 4 ± 0.33 U/mL enzyme activity. Hence, this study shows similarity with our work as LR C8 (L. rhamnosus) displayed the highest cumulative enzyme activity between 6 h, 12 h, and 18 h of incubation and not showed a significant difference after 24 h with the highest producer strain (LP C6).

The α-galactosidase activity of six standard probiotic Lactobacillus cultures was evaluated by Hati (2012) under different incubation times (6 h, 12 h, 18 h, 24 h, 30 h) in soy milk medium. Maximum production of α-galactosidase enzyme (66.98 U/mg) was reported by C6 (L. rhamnosus) as compared with the other Lactobacillus cultures after 30 h of incubation. NCDC 19 (L. rhamnosus) also exhibited good α-galactosidase activity (41.86 U/mg) in soy milk medium. The production of α-galactosidase activity relies on the strain type and availability of oligosaccharides present in the medium.

Screening of Lactobacillus cultures on the basis of β-glucosidase activity

In the current investigation, ten Lactobacillus cultures were considered for evaluating the ability to produce β-glucosidase. Tochikura et al. (1986) and Tsangalis et al. (2002) reported that the fermented soy milk showed different degrees of β-glucosidase activity relying upon the types of starter culture.

From Table 2, it had been found that β-glucosidase activity was varying significantly (P < 0.05) with incubation times. It was observed that the β-glucosidase activity of Lactobacillus cultures was enhanced significantly with incubation periods. Likewise, there was a significant difference (P < 0.05) noticed within the cultures for the production of β-glucosidase. After 24 h of incubation at 37 °C, NK9 exhibited the highest activity (1.76 U/mL), followed by M2 (L. fermentum) (1.74 U/mL). In contrast, M3 (L. fermentum) (1.67 U/mL) and M16 (L. fermentum) (1.67 U/mL) had the same enzymatic activity during fermentation in soy milk medium. However, M11 (L. paracasei) and M4 (L. fermentum) showed minimum β-glucosidase activity (0.76 and 0.84 U/mL). It was statistically observed that the response presented by NK9 (L. casei) was significantly higher (P < 0.05) than the other cultures.

Mishra et al. (2017) found highest enzyme activity by K4 (L. rhamnosus) as 0.396 μM/mL followed by K5 (L. fermentum) with 0.361 μM/mL and K14 (L. helveticus) with 0.332 μM/mL during fermentation in soy milk medium and this result supported our findings. Rekha and Vijayalakshmi (2011), reported L. fermentum BM-325 strain which is commonly dynamic, indicating higher β-glucosidase action (97.7 ± 3.9 U/mL) at 20 h of fermentation than other Lactobacillus strains. Otieno et al. (2006), noticed the highest β-glucosidase activity produced by L. rhamnosus 4692 than other strains. Donkor and Shah (2008) also observed the enhanced production of β-glucosidase by L. acidophilus L10 within 12 and 18 h than L. casei L26.

Hati et al. (2017) also studied the β-glucosidase activity of four lactic cultures V3 (L. helveticus) and showed the highest activity of 0.86 U/mL, followed by NS4 (L. rhamnosus) 0.81 U/mL in soy milk medium. The lowest activity was observed in 09 (L. bulgaricus) and MD2 (S. thermophillus) of 0.27 and 0.001 U/mL, respectively. Further, Hati et al. (2015a) reported β-glucosidase activity of six Lactobacillus cultures that exhibited different levels of β-glucosidase activity during their growth under optimal conditions and L. rhamnosus C6 exhibited the maximum activity (1.66 U/mL) among the others. Many lactobacilli possess β-glucosidase, including Lactobacillus acidophilus (Chien et al. 2006; Wei et al. 2007), Lactobacillus casei, Lactobacillus rhamnosus (Tang et al. 2007), Lactobacillus rhamnosus, and Lactobacillus delbrueckii ssp. bulgaricus (Pyo et al. 2005).

Evaluation of the growth behaviour of lactic cultures in soy milk

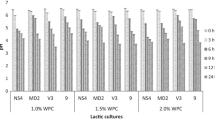

Ten active Lactobacillus cultures were added in sterilized soy milk at 2% (v/v) and sub-cultured two to three times for enhancing their physiological status. Active cultures were added in soy milk at 37 °C. Samples were analyzed at different intervals such as 0 h, 3 h, 6 h, 9 h, 12 h, 15 h and 18 h. During the evaluation of growth behavior of ten Lactobacillus cultures, it had been observed that pH and viable counts were differing significantly (P < 0.05) with incubation periods, whereas acidity (%LA; lactic acid) was significantly differing with an incubation period. Furthermore, a significant difference (P < 0.05) was observed within the cultures. It was observed that pH value of all ten Lactobacillus cultures was decreased, while the acidity and viable counts were increased with the time of incubation. All the strains were found to reach the stationary phase in between 12 h to 18 h, and a log count increased till 18 h of incubation. From Fig. 1, it was observed that the pH of the soy milk was gradually declined with the progression of fermentation. Maximum pH reduction was observed in M2 culture (pH 6.14 to 5.33), followed by V3 culture (pH 6.15 to 5.38) and NK9 (pH 6.28 to 5.40) after 18 h. However, M11 and M16 did not attain the desired pH during fermentation.

Initial titratable acidity of unfermented soy milk (0 h of incubation) was in the range of 0.06 to 0.08% lactic acid (LA), and final acidity reached 0.26% LA at after 18 h (Fig. 2). M2 showed maximum acidity (0.26% LA), followed by NK9 (0.25%LA). Minimum lactic acid was produced by M16 (0.15% LA) and M11 (0.17% LA). It is due to the lack of α-galactosidase enzyme production by the cultures for utilizing sucrose and other oligosaccharides in soy milk. Viable counts were increased from 4.22 to 4.52 log CFU/mL to 5.57 to 7.19 log CFU/mL (Fig. 3). Thus, it was observed that viable counts of 3 log cycle were increased by M2 (7.19 log CFU/mL) and NK9 (7.16 log CFU/mL), which is desirable for good fermented products. Similarly, slow acid production was also noticed in other strains. Hence, M2 and NK9 were the best choice for the preparation of the fermented soy-based beverage.

After 12 h of incubation, among the two mixed dahi cultures, NCDC323 indicated the greatest acidity (0.74% LA), trailed by NCDC167 (0.69% LA). Further, NCDC323 culture was the fast acid producer in soy milk (0.71% LA) after 8 h of incubation and 0.74% acidity after 12 h of incubation (Hati 2012). Mital et al. (1974) had likewise revealed that specific lactic cultures, for example, S. thermophilus, L. acidophilus, L. cellobiosis, and L. plantarum, which used sucrose, produced acid in soy milk. Soy milk had been established as a suitable growth medium for some LAB (Liu et al. 2002).

Hati et al. (2018) also studied the growth performance of eight selected lactic acid bacteria by determining viable counts (log CFU/mL) and production of lactic acid (%) measured by a decline in pH in soy milk inoculated at the rate of 2% (v/v) at 37 °C for 24 h. L. bulgaricus NCDC 09 and S. thermophilus MD2 were lowered down the pH of soy milk in the greatest amount. Acid production (titratable acidity) by L. bulgaricus NCDC 09 and L. helveticus V3 was higher as compared to different strains. Higher viable counts were noticed in S. thermophiles MD2 and L. helveticus V3. It was also concluded that viable cell counts, pH, and acidity vary due to the use of different strains (Hati et al. 2018) as found in our study. All the strains studied showed good growth in soy milk. The decrease of pH could be mostly because of the gathering of natural acids released by lactobacilli during fermentation (Gan et al. 2017).

After 24 h fermentation, the pH had declined from 7.03 ± 0.04 to 3.43 ± 0.01 by NCDC 288. Though, pH decreased by LR C25 (3.91 ± 0.06) was recorded minimum (P < 0.001) than reference strain NCDC 288. L. helveticus NCDC 288 showed viable counts 10.46 ± 0.003 log CFU/mL after 24 h of incubation during fermentation of soy milk (Singh and Vij 2018). Most of the strains produced acidity, viable counts in between 0 h to 18 h of incubation. Gan et al. (2017) further expressed that the suitable cell number of L. plantarum strain WCFS1 sharply increased at 9 h of fermentation in soy milk. In addition, L. plantarum B1–6 was also produced maximum, viable counts at around 10 h of fermentation in soy whey medium (Xiao et al. 2015). Moreover, Chun et al. (2007) reported that distinctive LAB strains displayed higher cell populations in soy milk. But L. plantarum strain BHM10 was unable to ferment soy milk (Bhushan et al. 2017).

Proteolytic activity of Lactobacillus cultures in soy milk

The starter and non-starter microorganisms engaged in the manufacturing of fermented dairy products are considered to release bioactive peptides. The LAB, for example, Lactococcus lactis, Lactobacillus helveticus and Lb. delbrueckii ssp. bulgaricus contains a cell wall-bound proteinase and various typical intracellular peptidases, containing endopeptidases, aminopeptidases, tripeptidases, and dipeptidases, which are liable for their proteolytic system (Christensen et al. 1999). Table 3 exhibited the proteolytic activity of soy milk fermented with M2 and NK9 cultures. After incubation, M2 showed maximum proteolytic activity (0.67), then NK9 (0.48) during fermentation of soy milk.

It was experienced that the degree of proteolysis depends on strains and time of incubation (Donkor et al. 2007). The study revealed the proteolysis of eight LAB, for example, S. thermophilus MD2, L. helveticus V3, L. rhamnosus NS6, L. rhamnosus NS4, L. bulgaricus NCDC 09, L. acidophilus NCDC 15, L. acidophilus NCDC 298 and L. helveticus NCDC 292 in skim and soy milk. Higher proteolysis was produced by S. thermophilus MD2 and L. rhamnosus NS6 in both skim and soy milk among all the lactic cultures, but all performed better in skim milk than soy milk (Subrota et al. 2013). Hati (2012) reported that L. rhamnosus C6 produced highest proteolytic activity as 565.83 (lg serine/mL) in soy milk. Probiotic strain L. helveticus M92 demonstrated the proteolytic (Beganović et al. 2013). Lactobacillus plantarum NRRL B-4004 was also the most proteolytic, which hydrolyzed alpha-casein after 215 h Khalid and Marth (1990).

ACE-inhibitory activity of Lactobacillus cultures in soy milk

ACE inhibitory activity of fermented soy milk is one of the most important attributes of the biofunctional property. Changes in ACE inhibitory activity (%) of fermented soy milk has been shown in Table 4. The data indicated that the ACE inhibitory activity was 48.44 and 41.33% for soy milk fermented with M2 and NK9, respectively. Soy milk fermented with M2 contributed to higher ACE inhibitory activity than NK9.

This was supported by many workers who found a significant percentage of ACE inhibitory activity in fermented soy milk. Bhatnagar et al. (2018) studied the different strains for their ACE inhibitory activity in fermented soy milk. The ACE inhibitory activity was found in fermented soy milk prepared with Lactobacillus paracasei CD4 (41.66%) and Brevibacillus thermoruber HM34 (6.90%) than the other cultures. It is because of various metabolic activities of lactic acid bacteria during the fermentation of soy milk. The soy milk fermented with various lactic acid bacteria, for example, L. casei, L. acidophilus, S. thermophilus, L. bulgaricus strains (Vallabha and Tiku 2014) had likewise demonstrated the ACE inhibitory activity.

In probiotic soy dahi, Hati (2012) reported the release of ACE inhibitory molecules which exhibited remarkable in vitro ACE inhibitory activity. NCDC 323 + C6 have altogether (P < 0.05) higher value (75.91%) of ACE inhibitory activity, than C6 (62.78%) and NCDC 323 (56.21%), and minimum with unfermented soy milk (41.22%).

Soy yogurt made with probiotic strains as an additional culture produced maximum ACE inhibitory activity (Bozanic et al. 2011). The probiotic soy yogurt containing higher amounts of bioactive ACE inhibitors may contribute biofunctional compounds as a functional fermented milk product (Donkor et al. 2005). Further, the greatest ACE inhibition was recorded with MD2 (60.41%), than NS4 (55.00%) and V3 (54.57%) (Hati et al. 2018). These reports showed improved ACE inhibitory activity after fermentation of soy milk, which supports our findings. The outcomes showed that fermented soy milk could be a good source of ACE inhibitory activity and utilized for prevention and treatment of hypertension.

Analysis of peptide with antihypertensive activity from fermented soy milk using M2 and NK9

Peptide identification by mass spectrometry

The trypsin digested peptides have been evaluated under MALDI TOF analysis to characterize the peptide sequence and also to recognize the peptides on NCBI/BLAST under the mammalian protein database. Figure 4 shows the RP-HPLC chromatogram of 3 kDa permeate of fermented soy milk produced by strains M2 and NK9. Here, four novel peptides from fermented soy milk were identified and presented in Table 5; and identified mass spectra have also been visualized in Fig. 5. Identified peptides were SGLGRGWIDGDIGHGK and SMEDMM from fermented soy milk with M2 as well as VPVVLGSKNEVDYIK, GYHYVGTLSGHTK, VREDGVYCEIVPFQK, TPPASWSKLGYK from fermented soy milk with NK9. Further, GHG (Balti et al. 2010), MM (Anna et al. 2016), TLS (Wu et al. 2013), GYK (Meisel et al. 2006) peptide sequences with ACE inhibitory activity were matched with us completely in BIOPEP database.

Conclusion

Out of ten Lactobacillus cultures, two Lactobacillus cultures (M2 and NK9) were screened based on α-galactosidase and β-glucosidase activity in soy milk medium. M2 and NK9 also showed good growth behavior as compared to other Lactobacillus cultures in soy milk. For the release of bioactive peptides from soy milk, two selected Lactobacillus cultures also showed better proteolytic and ACE-inhibitory activity. Fermented soy milk released potent ACE-inhibitory peptides such as SGLGRGWIDGDIGHGK and SMEDMM by M2 and VPVVLGSKNEVDYIK, GYHYVGTLSGHTK, VREDGVYCEIVPFQK, TPPASWSKLGYK by NK9. Further, additional studies are required to optimize the production of these peptides during fermentation and also to explore the commercial feasibility for enhancing biofunctional properties of fermented soy products with particular health claims.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article. Further details are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ACE:

-

Angiotensin-converting enzyme

- MALDI-TOF:

-

Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization-Time of Flight

- LAB:

-

Lactic acid bacteria

- pNPG:

-

P-nitrophenyl-α-D galactopyranoside/ p-nitrophenol β-D-glucopyranoside

- OPA:

-

O-phthalaldehyde

- HHL:

-

Hippuryl-L-histidyl-L-leucine

- HCCA:

-

Α-cyano-4-hydroxycynnamic acid

- LA:

-

Lactic acid

- NCDC:

-

National Collection of Dairy Cultures

References

Abubakar, A., Saito, T., Kitazawa, H., Kawai, Y., & Itoh, T. (1998). Structural analysis of new antihypertensive peptides derived from cheese whey protein by proteinase K digestion. Journal of Dairy Science, 81(12), 3131–3138. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(98)75878-3.

Abraham, A., Giri, S. K., Tripathi, M. K., Singh, R., Devi, W. E., & Shukla, V. (2014). Optimization of fermentation conditions for the development of probiotic soymilk using Lactobacillus paracasei ssp. paracasei 013 strain. International Journal of Research in Advanced Engineering and Technology, 2(3), 1–8.

Agyei, D., & Danquah, M. K. (2011). Industrial-scale manufacturing of pharmaceutical-grade bioactive peptides. Biotechnology Advances, 29(3), 272–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biotechadv.2011.01.001.

Akabanda, F., Owusu-Kwarteng, J. R. L. K., Glover, R. L. K., & Tano-Debrah, K. (2010). Microbiological characteristics of Ghanaian traditional fermented milk product, Nunu. Nature and Science, 8(9), 178–187.

Anna, T., Alexey, K., Anna, B., Vyacheslav, K., Mikhail, T., & Ulia, M. (2016). Effect of in vitro gastrointestinal digestion on bioactivity of poultry protein hydrolysate. Current Research in Nutrition and Food Science, J4, 77–86.

Balti, R., Bougatef, A., Sila, A., Guillochon, D., Dhulster, P., & Nedjar-Arroume, N. (2015). Nine novel angiotensin I-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitory peptides from cuttlefish (Sepia officinalis) muscle protein hydrolysates and antihypertensive effect of the potent active peptide in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Food Chemistry, 170, 519–525. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.03.091.

Balti, R., Nedjar-Arroume, N., Adje, E. Y., Guillochon, D., & Nasri, M. (2010). Analysis of novel angiotensin I-converting enzyme inhibitory peptides from enzymatic hydrolysates of cuttlefish (Sepia officinalis) muscle proteins. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 58(6), 3840–3846. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf904300q.

Beganović, J., Kos, B., Pavunc, A. L., Uroić, K., Dzidara, P., & Susković, J. (2013). Proteolytic activity of probiotic strain lactobacillus helveticus M92. Anaerobe, 20, 58–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anaerobe.2013.02.004.

Bhatnagar, M., Attri, S., Sharma, K., & Goel, G. (2018). Lactobacillus paracasei CD4 as potential indigenous lactic cultures with antioxidative and ACE inhibitory activity in soy milk hydrolysate. Journal of Food Measurement and Characterization, 12(2), 1005–1010.

Bhushan, B., Tomar, S. K., & Chauhan, A. (2017). Techno-functional differentiation of two vitamin B12 producing lactobacillus plantarum strains: An elucidation for diverse future use. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 101(2), 697–709. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-016-7903-z.

Bozanic, R., Lovkovic, S., & Jelicic, I. (2011). Optimising fermentation of soy milk with probiotic bacteria. Journal of Food Science, 29(1), 51–56.

Chang, S. K., Ismail, A., Yanagita, T., Esa, N. M., & Baharuldin, M. T. H. (2015). Antioxidant peptides purified and identified from the oil palm (ElaeisguineensisJacq.) kernel protein hydrolysate. Journal of Functional Foods, 14, 63–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jff.2015.01.011.

Chien, H. L., Huang, H. Y., & Chou, C. C. (2006). Transformation of isoflavone phytoestrogens during the fermentation of soy milk with lactic acid bacteria and bifidobacteria. Food Microbiology, 23(8), 772–778. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fm.2006.01.002.

Christensen, J. E., Dudley, E. G., Pederson, J. A., & Steele, J. L. (1999). Peptidases and amino acid catabolism in lactic acid bacteria. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek, 76(1–4), 217–246. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1002001919720.

Chun, J., Kim, G. M., Lee, K. W., Choi, I. D., Kwon, G. H., Park, J. Y., & Kim, J. H. (2007). Conversion of isoflavone glucosides to aglycones in soy milk by fermentation with lactic acid bacteria. Journal of Food Science, 72(2), M39–M44. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-3841.2007.00276.x.

Cushman, D. W., & Cheung, H. S. (1971). Spectrophotometric assay and properties of the angiotensin-converting enzyme of rabbit lung. Biochemical Pharmacology, 20(7), 1637–1648. https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-2952(71)90292-9.

Donkor, O. N., Henriksson, A., Vasiljevic, T., & Shah, N. P. (2005). Probiotic strains as starter cultures improve angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitory activity in soy yogurt. Journal of Food Science, 70(8), m375–m381. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2621.2005.tb11522.x.

Donkor, O. N., Henriksson, A., Vasiljevic, T., & Shah, N. P. (2007). α-Galactosidase and proteolytic activities of selected probiotic and dairy cultures in fermented soy milk. Food Chemistry, 104(1), 10–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.10.065.

Donkor, O. N., & Shah, N. P. (2008). Production of β‐Glucosidase and Hydrolysis of Isoflavone Phytoestrogens by Lactobacillus acidophilus, Bifidobacterium lactis, and Lactobacillus casei in Soymilk. Journal of Food Science, 73(1), M15–M20. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-3841.2007.00547.x.

Downes, F. P., & Ito, K. (2001). Compendium of methods for the microbiological examination of foods. Washington DC: American Public Health Association.

FSSAI (2015). Determination of total carbohydrates in dried milk. In manual of methods of analysis of foods. New Delhi: Milk & Milk Products. Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, Government of India.

Gan, R. Y., Shah, N. P., Wang, M. F., Lui, W. Y., & Corke, H. (2017). Lactobacillus plantarum WCFS1 fermentation differentially affects antioxidant capacity and polyphenol content in mung bean (Vigna radiata) and soya bean (Glycine max) milks. Journal of Food Processing and Preservation, 41(1), e12944. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfpp.12944.

Hati, S. (2012). Biofunctional properties of probiotic soy dahiDoctoral dissertation. Karnal: NDRI.

Hati, S., Patel, N., & Mandal, S. (2018). Comparative growth behaviour and biofunctionality of lactic acid bacteria during fermentation of soy milk and bovine milk. Probiotics and Antimicrobial Proteins, 10(2), 277–283. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12602-017-9279-5.

Hati, S., Patel, N., Patel, K., & Prajapati, J. B. (2017). Impact of whey protein concentrate on proteolytic lactic cultures for the production of isoflavones during fermentation of soy milk. Journal of Food Processing and Preservation, 41(6), e13287. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfpp.13287.

Hati, S., Sreeja, V., Solanki, J., & Prajapati, J. B. (2015a). Significance of proteolytic microorganisms on ACE-inhibitory activity and release of bioactive peptides during fermentation of milk. Indian Journal of Dairy Science, 68(6). https://doi.org/10.5146/IJDS.V68I6.44661.G23233.

Hati, S., Vij, S., Mandal, S., Malik, R. K., Kumari, V., & Khetra, Y. (2014). α-Galactosidase activity and oligosaccharides utilization by lactobacilli during fermentation of soy milk. Journal of Food Processing and Preservation, 38(3), 1065–1071. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfpp.12063.

Hati, S., Vij, S., Singh, B. P., & Mandal, S. (2015b). β-Glucosidase activity and bioconversion of isoflavones during fermentation of soy milk. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 95(1), 216–220. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.6743.

Inoue, K., Gotou, T., Kitajima, H., Mizuno, S., Nakazawa, T., & Yamamoto, N. (2009). Release of antihypertensive peptides in miso paste during its fermentation, by the addition of casein. Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering, 108, 111–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiosc.2009.03.007.

Iroyukifujita, H., Eiichiyokoyama, K., & Yoshikawa, M. (2000). Classification and antihypertensive activity of angiotensin I-converting enzyme inhibitory peptides derived from food proteins. Journal of Food Science, 65(4), 564–569. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2621.2000.tb16049.x.

Katayama, K., Jamhari, M. T., Kawahara, S., Miake, K., Kodama, Y., & Muguruma, M. (2007). Angiotensin-I converting enzyme inhibitory peptide derived from porcine skeletal muscle myosin and its antihypertensive activity in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Journal of Food Science, 72(9), S702–S706. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-3841.2007.00571.x.

Khalid, N. M., & Marth, E. H. (1990). Proteolytic activity by strains of lactobacillus plantarum and lactobacillus casei. American Dairy Science Association, 73, 3068–3076. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(90)78994-1.

Kulkarni, D. S., Kapanoor, S. S., Girigouda, K., Kote, N. V., & Mulimani, V. H. (2006). Reduction of flatus-inducing factors in soy milk by immobilized α-galactosidase. Biotechnology and Applied Biochemistry, 45(2), 51–57. https://doi.org/10.1042/BA20060027.

Lee, N., Cheng, J., Enomoto, T., & Nakano, Y. O. S. H. I. H. I. S. A. (2006). One peptide derived from hen ovotransferrin as pro-drug to inhibit angiotensin converting enzyme. Journal of Food and Drug Analysis, 14(1), 31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.01.033.

Liu, J. R., Wang, S. Y., Lin, Y. Y., & Lin, C. W. (2002). Antitumor activity of milk kefir and soy milk kefir in tumor-bearing mice. Nutrition and Cancer, 44(2), 183–187. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327914NC4402_10.

Mallikarjun Gouda, K. G., Gowda, L. R., Rao, A. A., & Prakash, V. (2006). Angiotensin I-converting enzyme inhibitory peptide derived from glycinin, the 11S globulin of soybean (Glycine max). Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 54(13), 4568–4573. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf060264q.

Meisel, H., Walsh, D. J., Murray, B., & FitzGerald, R. J. (2006). Nutraceutical proteins and peptides in health and disease. ACE inhibitory peptides. In Y. Mine, & F. Shahidi (Eds.), Nutraceutical science technology, (pp. 269–315).

Mishra, B. K., Hati, S., Das, S., Mishra, S., & Mandal, S. (2017). α-Galactosidase and β-glucosidase enzyme activity of lactic strains isolated from traditional fermented foods of west Garo Hills, Meghalaya. International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences, 6, 1193–1201. https://doi.org/10.20546/ijcmas.2017.604.146.

Mital, B. K., & Steinkraus, K. H. (1975). Utilization of oligosaccharides by lactic acid bacteria during fermentation of soy milk. Journal of Food Science, 40(1), 114–118. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2621.1975.tb03749.x.

Mital, B. K., Steinkraus, K. H., & Naylor, H. B. (1974). Growth of lactic acid bacteria in soy milks. Journal of Food Science, 39(5), 1018–1022. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2621.1974.tb07300.x.

Mito, K., Fujii, M., Kuwahara, M., Matsumura, N., Shimizu, T., Sugano, S., & Karaki, H. (1996). Antihypertensive effect of angiotensin I-converting enzyme inhibitory peptides dived from hemoglobin. The European Journal of Pharmacology, 304(1–3), 93–98.

Moayedi, A., Mora, L., Aristoy, M. C., Safari, M., Hashemi, M., & Toldrá, F. (2018). Peptidomic analysis of antioxidant and ACE-inhibitory peptides obtained from tomato waste proteins fermented using Bacillus subtilis. Food Chemistry, 250, 180–187.

Mojica, L., Chen, K., & de Mejía, E. G. (2015). Impact of commercial precooking of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) on the generation of peptides, after pepsin-pancreatin hydrolysis, capable to inhibit dipeptidyl peptidase-IV. Journal of Food Science, 80(1), H188–H198. https://doi.org/10.1111/1750-3841.12726.

Nelson, A. I., Steinberg, M. I., & Wei, L. S. (1976). Illinois process for preparation of soy milk. Journal of Food Science, 41(1), 57–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2621.1976.tb01100.x.

O'Keeffe, M. B., Norris, R., Alashi, M. A., Aluko, R. E., & FitzGerald, R. J. (2017). Peptide identification in a porcine gelatin prolylendoproteinase hydrolysate with angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitory and hypotensive activity. Journal of Functional Foods, 34, 77–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jff.2017.04.018.

Otieno, D. O., Ashton, J. F., & Shah, N. P. (2006). Evaluation of enzymic potential for biotransformation of isoflavone phytoestrogen in soy milk by Bifidobacterium animalis, lactobacillus acidophilus and lactobacillus casei. Food Research International, 39(4), 394–407. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2005.08.010.

Pyo, Y. H., Lee, T. C., & Lee, Y. C. (2005). Effect of lactic acid fermentation on enrichment of antioxidant properties and bioactive isoflavones in soybean. Journal of Food Science, 70(3), S215–S220. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2621.2005.tb07160.x.

Qian, Z. J., Je, J. Y., & Kim, S. K. (2007). Antihypertensive effect of angiotensin I converting enzyme-inhibitory peptide from hydrolysates of bigeye tuna dark muscle, Thunnusobesus. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 55(21), 8398–8403. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf0710635.

Ranganna, S. (2012). Handbook of analysis and quality control for fruit and vegetable products, (2nd ed., ). New Delhi: Tata McGraw hill education private limited.

Rekha, C. R., & Vijayalakshmi, G. (2011). Isoflavone phytoestrogens in soy milk fermented with β-glucosidase producing probiotic lactic acid bacteria. International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition, 62(2), 111–120. https://doi.org/10.3109/09637486.2010.513680.

Scalabrini, P., Rossi, M., Spettoli, P., & Matteuzzi, D. (1998). Characterization of Bifidobacterium strains for use in soy milk fermentation. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 39(3), 213–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-1605(98)00005-1.

Singh, B. P., & Vij, S. (2018). α-Galactosidase activity and oligosaccharides reduction pattern of indigenous lactobacilli during fermentation of soy milk. Food Bioscience, 22, 32–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fbio.2018.01.002.

Singh, B. P., Vij, S., & Hati, S. (2014). Functional significance of bioactive peptides derived from soybean. Peptides, 54, 171–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.peptides.2014.01.022.

Singh, B. P., Yadav, D., & Vij, S. (2017). Soybean bioactive molecules: Current trend and future prospective. In: Mérillon JM., Ramawat K. (eds). Bioactive Molecules in Food. Reference Series in Phytochemistry. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-54528-8_4-1.

Solanki, D., Hati, S., & Sakure, A. (2017). In silico and in vitro analysis of novel angiotensin I-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitory bioactive peptides derived from fermented camel milk (Camelus dromedarius). International Journal of Peptide Research and Therapeutics, 23(4), 441–459. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10989-017-9577-5.

Stuknytė, M., Cattaneo, S., Masotti, F., & De Noni, I. (2015). Occurrence and fate of ACE-inhibitor peptides in cheeses and in their digestates following in vitro static gastrointestinal digestion. Food Chemistry, 168, 27–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.07.045.

Subrota, H., Shilpa, V., Brij, S., Vandna, K., & Surajit, M. (2013). Antioxidative activity and polyphenol content in fermented soy milk supplemented with WPC-70 by probiotic lactobacilli. International Food Research Journal, 20(5), 2125.

Suetsuna, K., & Chen, J. R. (2001). Identification of antihypertensive peptides from peptic digest of two microalgae, Chlorella vulgaris and Spirulinaplatensis. Marine Biotechnology, 3(4), 305–309.

Tang, A. L., Shah, N. P., Wilcox, G., Walker, K. Z., & Stojanovska, L. (2007). Fermentation of calcium-fortified soy milk with lactobacillus: Effects on calcium solubility, isoflavone conversion, and production of organic acids. Journal of Food Science, 72(9), M431–M436. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-3841.2007.00520.x.

Tanzadehpanah, H., Asoodeh, A., Saberi, M. R., & Chamani, J. (2013). Identification of a novel angiotensin-I converting enzyme inhibitory peptide from ostrich egg white and studying its interactions with the enzyme. Innovative Food Science and Emerging Technologies, 18, 212–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ifset.2013.02.002.

Tochikura, T., Sakai, K., Fujiyoshi, T., TACHIKI, T., & Kumagai, H. (1986). P-Nitrophenyl glycoside-hydrolyzing activities in bifidobacteria and characterization of β-D-galactosidase of Bifidobacterium longum 401. Agricultural and Biological Chemistry, 50(9), 2279–2286. https://doi.org/10.1271/bbb1961.50.2279.

Tsai, J. S., Lin, Y. S., Pan, B. S., & Chen, T. J. (2006). Antihypertensive peptides and γ-aminobutyric acid from prozyme 6 facilitated lactic acid bacteria fermentation of soy milk. Process Biochemistry, 41(6), 1282–1288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procbio.2005.12.026.

Tsangalis, D., Ashton, J. F., McGill, A. E. J., & Shah, N. P. (2002). Enzymic transformation of isoflavone phytoestrogens in soy milk by β-glucosidase-producing bifidobacteria. Journal of Food Science, 67(8), 3104–3113. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2621.2002.tb08866.x.

Tsangalis, D., Ashton, J. F., Stojanovska, L., Wilcox, G., & Shah, N. P. (2004). Development of an isoflavone aglycone-enriched soy milk using soy germ, soy protein isolate and bifidobacteria. Food Research International, 37(4), 301–312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2004.01.003.

Vallabha, V. S., & Tiku, P. K. (2014). Antihypertensive peptides derived from soy protein by fermentation. International Journal of Peptide Research and Therapeutics, 20, 161–168. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10989-013-9377-5.

Ven, C. (2002). Biochemical and functional characterization of casein and whey protein hydrolysates: A study on the correlations between biochemical and functional properties using multivariate data analysis (doctoral dissertation, Sl: Sn).

Villegas, J. M., Picariello, G., Mamone, G., Turbay, M. B. E., de Giori, G. S., & Hebert, E. M. (2014). Milk-derived angiotensin-I-converting enzymeinhibitory peptides generated by lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. lactis CRL 581. Peptidomics, 1(1). https://doi.org/10.2478/ped-2014-0002.

Wang, J., Wu, R., Zhang, W., Sun, Z., Zhao, W., & Zhang, H. (2013). Proteomic comparison of the probiotic bacterium lactobacillus casei Zhang cultivated in milk and soy milk. Journal of Dairy Science, 96(9), 5603–5624. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2013-6927.

Wang, L. Q. (2002). Mammalian phytoestrogens: Enterodiol and enterolactone. Journal of Chromatography B, 777(1–2), 289–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1570-0232(02)00281-7.

Wei, Q. K., Chen, T. R., & Chen, J. T. (2007). Using of lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium to product the isoflavone aglycones in fermented soy milk. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 117(1), 120–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2007.02.024.

Wu, C., Jia, S., Fan, G., Li, T., Ying, R., & Yang, J. (2013). Purification and identification of novel antioxidant peptides from enzymatic hydrolysate of Ginkgo biloba seed proteins. Food Science and Technology Research, 19(6), 1029–1035.

Wu, J., Aluko, R. E., & Nakai, S. (2006). Structural requirements of angiotensin I-converting enzyme inhibitory peptides: Quantitative structure-activity relationship study of di-and tripeptides. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 54(3), 732–738. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf051263l.

Xiao, Y., Wang, L., Rui, X., Li, W., Chen, X., Jiang, M., & Dong, M. (2015). Enhancement of the antioxidant capacity of soy whey by fermentation with lactobacillus plantarum B1–6. Journal of Functional Foods, 12, 33–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jff.2014.10.033.

Zielińska, E., Baraniak, B., & Karaś, M. (2018). Identification of antioxidant and anti-inflammatory peptides obtained by simulated gastrointestinal digestion of three edible insects species (Gryllodessigillatus, Tenebriomolitor, Schistocercagragaria). International Journal of Food Science and Technology, 53(11), 2542–2551. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijfs.13848.

Acknowledgments

The authors are highly thankful to NABI, Mohali, Punjab, India for facilitating the peptide analysis through MALDO-TOF system.

Funding

No Funding is being received for the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SH supervised and designed the study. UT performed the experiments and obtained the data. UT, SD and SH analyzed and interpreted the results. UT, SD, DS, and DK wrote, edited, and formatted the article. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Declarations of interest: none.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Undhad Trupti, J., Das, S., Solanki, D. et al. Bioactivities and ACE-inhibitory peptides releasing potential of lactic acid bacteria in fermented soy milk. Food Prod Process and Nutr 3, 10 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43014-021-00056-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43014-021-00056-y