Abstract

The assessment of melting heat transfer and non-uniform heat source on magnetic Cu–H2O nanofluid flow through a porous cylinder was studied. The transformed differential equations describing the motion of Cu–H2O fluid together with pertinent boundary conditions were handled numerically with the assistance of Keller box method. The ranges of volume fraction of copper particles were taken as 0–25%. The impacts of various governing parameters on the physical measures such as Nusselt number, surface drag force, temperature and velocity were analyzed by representing through graphs and tables. It was noted that the flow was influenced accordingly with the governing parameters. The outcomes showed that the rate of heat exchange improved with elevated Reynolds number, space and temperature-dependent internal heat source and melting parameters. The comparison of our data in relation to those of previous works has been shown.

Similar content being viewed by others

Highlights

-

Assessment of melting heat transfer and non-uniform heat source on magnetic Cu–H2O nanofluid flow through a porous cylinder was studied.

-

The governing equations are solved by KBM (Keller box method).

-

A good agreement was created with the experimental results.

-

With increase in porous parameter values, the heat transfer rate declined near the surface.

-

The coefficient of surface drag force depreciated with enhancing melting parameter values.

Introduction

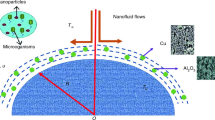

The nanofluids are liquid suspensions of nano-sized solid particles into the base liquids. In the last few decades, the term nanofluid has become an interesting topic among the different research communities because of its rapid capacity of heat exchange. This has resulted in broad utilization of nanofluids in several manufacturing and technology applications such as energy storage, cancer therapy, melts of polymer paints, drug delivery, asphalts and glues. Choi and Eastman [1] were the first who proposed the term nanofluid and observed that the addition of nanoparticles in traditional fluids fairly improved the thermal conductivity of fluid. The utilization of heat exchange is in various industrial applications such as pasteurization of food, fuel cells, biomedicine/pharmaceutical processes and microelectronics. Wang [2] modeled the fluid transportation from a stretchable cylinder and found that temperature and velocity decay with higher variations of Reynolds number. Ishak et al. [3] examined the fluid motion and heat transfer via a stretching tube in the occurrence of suction/injection. Their results showed that the heat exchange declines with higher Pr values. Wang and Ng [4] elaborated fluid flow via a stretchable cylinder due to slip, and they stated that velocities as well as shear drag force reduced drastically with slip. Ashorynejad et al. [5] proposed heat transfer motion of nanoliquid via a stretching geometry in the occurrence of magnetic effects. Their outcomes revealed that heat exchange rate augments by an increment in variation of both nanoparticle volume fraction and Reynolds number, while it reduces by an increment in magnetic parameter values. Majeed et al. [6] discussed the mixed influence of prescribed heat flux at surface and partial slip on fluid flow along stretchable cylinder. From their results, they examined that velocity diminishes, while temperature boosts by the slip parameter. The analytic results of axisymmetric third-grade fluid flow via a stretchable cylinder in the occurrence of magnetic effects have been computed by Hayat et al. [7]. Their results demonstrated that axial velocity is a lessening function of magnetic field. Butt et al. [8] evaluated the role of magnetic field on the viscous flow and entropy generation via a porous stretching cylinder and observed that the permeability and magnetic field parameters have diminishing impacts on velocity; however, temperature amplifies with a rise in same parameters. Pandey and Kumar [9, 10] and Mishra et al. [11] inspected the boundary-layer transport and heat exchange of nanofluid via stretching cylinder influenced by different effects. Hayat et al. [12] deliberated the motion of viscoelastic liquid due to stretchable cylinder because of mixed convection impact. Ebrahimi et al. [13] discussed the role of melting heat exchange in fluid flow in the presence of heat exchanger influenced by U-shaped heat pipe. Khan and Malik [14, 15] investigated the behavior of Sisko nanofluid flow and heat exchange through a stretchable cylinder due to forced convective impact. Malik et al. [16] modeled the flow of Sisko liquid via a nonlinear stretching cylinder in the existence of Cattaneo–Christov heat flux. Ahmed et al. [17] created a model to study the influence of heat source/sink on boundary-layer transport of nanoliquid along stretchable and permeable tube. Pandey and Kumar [18] analyzed the effects of magnetic field in Cu–water nanoliquid motion through stretching/shrinking channel due to ohmic heating and heat absorption–generation. The characteristics of thermal radiation and heat absorption/generation transportation of nanoliquid from unsteady stretchable surface have been considered by Pandey and Kumar [19]. Singh and Kumar [20] analyzed the mixed effects of melting on the boundary-layer transport and heat exchange due to stretching sheet in micro-polar liquid. Singh and Kumar [21] formulated a problem to examine the impact of melting heat exchange in motion of micro-polar fluid via stretching/shrinking surface due to magnetic field effect. Pandey and Kumar [22] proposed the mixed impacts of melting and suction–blowing on the magnetic nanoliquid flow in a wedge implanted in porous medium with slip impact. Singh et al. [23] analyzed the stagnation point slip flow and heat exchange of micro-polar liquid due to shrinking surface. Hayat et al. [24] considered the role of slip effects and Joule heating on the peristaltic motion of MHD tangent hyperbolic nanofluid along inclined channel. Hayat et al. [25] observed the influence of Joule heating and melting heat transfer on Cu–water fluid flow. The influence of magnetic field on several geometries was done by [26,27,28,29,30,31,32].

Mathematical formulation

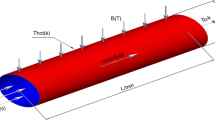

The model deals with a laminar, steady, incompressible and axisymmetric motion of a Cu–water nanofluid via a porous flat stretching pipe with diameter 2a, r-axis is perpendicular to the pipe, and z-axis is along the direction of the pipe. The pipe is being stretched with velocity \(W_{w} = 2cz\) along z-axis where stretching rate is c. The model is in the existence of the melting heat transfer, non-uniform heat source and a uniform magnetic field of strength of \(B_{0}\) imposed in the direction of r-axis. The graphical depiction of the model is exhibited together with configuration of flow and coordinate system in Fig. 1. The temperature of melting surface and free stream is \(T_{{\text{m}}}\) and \(T_{\infty }\). It is also considered that \(T_{{\text{s}}}\) is solid medium temperature distanced the interface, and \(T_{{\text{s}}} < T_{{\text{m}}}\). The thermal radiation, ohmic dissipation and ohmic heating effects are assumed to be negligible. The physical properties of H2O and nanoparticles are depicted in Table 1. Under these all above postulations, the boundary-layer equations are given as follows:

Boundary conditions of the model are

Now, \(q^{\prime \prime \prime }\) is defined as

where \(Q\) and \(Q_{0}\) are internal heat source parameters.

The theoretical model for nanofluid transport is defined as follows [11, 18, 32,33,34]:

The partial differential Eqs. (1)–(4) of the governing flow of nanofluid are changed into the ordinary differential equations by utilizing the similarity variable as

The changed ordinary differential equations of flow and thermal field are as follows:

The boundary equations reduced to

Here,

Now, the nanofluid pressure can be computed from Eq. (3) as follows:

The physical quantities of the most importance are Nusselt number and surface drag force (skin friction coefficient) and written as

where \(q_{w}\) is the heat transfer and \(\tau_{w}\) is the skin friction of cylindrical pipe, which are given as follows:

By the use of Eqs. (8) and (15), Eq. (14) reduces as follows:

Results and discussion

The transformed ordinary differential Eqs. (9) and (10) with Eq. (11) have been handled with the assistance of finite-difference method called Keller box method formed by Cebeci and Bradshaw [35]. To analyze impacts of assorted physical parameters on the motion of the micro-polar fluid, a numerical computation has been carried out for \(0 \le \Lambda \le 15,\) \(0.5 \le Q = Q_{0} \le 10,\) \(1 \le {\text{Re}} \le 10,\) \(0 \le m \le 0.2\) and \(0 \le \phi \le 0.25\). In the whole computation, values of some parameters are fixed as \(\Pr = 7,\) \(M = 1,\) \(S = 0.6\). In order to authenticate the numerical outcomes obtained, a comparison of present data with those of past studies is illustrated in Table 2 and is observed to be in a good conformity.

The impact of porosity parameter \(\Lambda\) on flow and thermal field is shown in Figs. 2 and 3, respectively. Figure 2 explain that as the value of porous parameter increased velocity boundary thickness of nanofluid constantly declined near the surface but there was no variation when the nanofluid moved away from the wall. The nanofluid temperature accelerates in the range of \(\eta \in \left[ {1,\;2} \right]\), but after this range there are no changes in thermal field of nanofluid as porosity parameter \(\Lambda\) escalates, which is observed in Fig. 3.

The outlines of velocity and thermal field of Cu–H2O nanofluid due to several values of \({\text{Re}}\) are revealed in Figs. 4 and 5, respectively. These asymptotic outlines verify the solutions for each value of pertinent parameter. The Cu–H2O nanofluid flow and thermal distributions are depreciated very fast as \({\text{Re}}\) escalates.

The activity of the thermal and flow field due to melting parameter \(m\) is demonstrated in Figs. 6 and 7, respectively. It is apparent from Fig. 6 that fluid velocity retards with escalating values of melting parameter. It is seen from Fig. 7 that the thermal layer width plus fluid temperature declines with enhancing melting parameter \(m\).

The distributions of velocity and temperature for the several values of space and temperature-dependent internal heat source parameters (\(Q\) and \(Q_{0}\)) are exhibited in Figs. 8 and 9, respectively. It is viewed from Fig. 8 that the velocity reduces slightly with growing \(Q\) and \(Q_{0}\). It is depicted from Fig. 9 that fluid thermal field diminishes monotonically with rising values of \(Q\) and \(Q_{0}\).

Figures 10 and 11 depict variation in velocity \(f^{\prime}(\eta )\) and temperature \(\theta (\eta )\) graphs, respectively, for various estimates of Cu particle volume fraction \(\phi\). It is evident from Fig. 10 that \(f^{\prime}(\eta )\) minimizes with escalating \(\phi\) values. It is seen from Fig. 11 that influence of mounting \(\phi\) is to enhance thermal boundary layer as well as nanofluid temperature \(\theta (\eta )\).

The influence of \({\text{Re}}\) and \(\Lambda\) on surface drag force (skin factor) is shown in Fig. 12. It is illustrated from these curves that the surface drag force monotonically lessens with a climb in \({\text{Re}}\) and \(\Lambda\) values. The deviation in Nusselt number \(- \theta ^{\prime}(1)\) (the surface heat transfer rate) with Reynolds number \({\text{Re}}\) and porous parameter \(\Lambda\) is shown in Fig. 13. The outlines illustrate that heat transfer rate boosts with a climb in Reynolds number \({\text{Re}}\), while this rate retards with mounting porous parameter \(\Lambda\).

Figure 14 explains the distribution of surface drag force (skin factor) \(f^{\prime\prime}(1)\) with respect to \({\text{Re}}\) for different estimates of \(Q = Q_{0}\). It is observed from these outlines \(f^{\prime\prime}(1)\) trim down with an augmentation in both \({\text{Re}}\) and \(Q = Q_{0}\) values; also from this figure, it is clear that reduction in \(f^{\prime\prime}(1)\) is more pronouncing for higher values of \({\text{Re}}\), i.e., for \({\text{Re}} > 4\). The profile of heat transfer rate \(\theta ^{\prime}(1)\) is described for relatable parameters in Fig. 15. Figure 15 portrays the actions of the heat transfer rate in opposition to Reynolds number \({\text{Re}}\) for various estimates of \(Q = Q_{0}\). These curves show that heat transfer rate mounts monotonically with enhancing values of \({\text{Re}}\) and \(Q = Q_{0}\). Table 3 demonstrates deviation in the surface drag force \(f^{\prime\prime}\left( 1 \right)\) and Nusselt Number \(- \theta ^{\prime}(1)\) (rate of heat exchange) for diverse numerical values of the used parameters in the present model. The data of this table are obtained by Keller box method. From this table, both skin factor and rate of heat exchange decline with the increasing values of porous parameter \(\Lambda\). Further, it is obvious that values of \(f^{\prime\prime}\left( 1 \right)\) retard with the higher Reynolds number \({\text{Re}}\) values, while Nusselt number boosts with the same values of Reynolds number. In addition, the rising values of melting parameter \(m\) cause a down fall in skin friction coefficient, while speeding up the rate of heat exchange. Moreover, it is obvious from this table that the heat exchange rate is proportional to internal heat source parameters (\(Q\) and \(Q_{0}\)), whereas there is a slight moderate in skin friction coefficient with \(Q = Q_{0}\) values.

Conclusions

The assessment of non-uniform heat source and melting heat transfer on magnetized Cu–H2O nanofluid via a stretching cylinder saturated in porous medium has been investigated. The outcomes of relatable parameters are achieved numerically by utilizing Keller box method. It is expected that the current investigations may be beneficial in several industrial applications. The main outcomes of this research are summarized as follows:

-

With increase in porous parameter values, the surface drag force and heat transfer rate declined near the surface.

-

It is seen that the surface drag force declines with augment in Reynolds number, whereas the upshot is contrary for Nusselt number \(- \theta ^{\prime}(1)\).

-

The coefficient of surface drag force depreciated with enhancing melting parameter values. Moreover, the rate of heat exchange also hikes.

-

The values of \(f^{\prime\prime}\left( 1 \right)\) reduce slightly with space and temperature-dependent internal heat source parameters, but the rate of heat exchange is proportional to same parameters.

Availability of data and materials

All the data generated and materials during this study are included in this research article.

Abbreviations

- A :

-

Constant

- B :

-

Constant

- B 0 :

-

Magnetic field strength

- C :

-

Constant

- c :

-

Stretching rate

- C f :

-

Skin friction coefficient

- D :

-

Constant

- f :

-

Non-dimensional stream function

- M :

-

Magnetic field parameter

- m :

-

Melting parameter

- Nu:

-

Nusselt number

- p :

-

Pressure

- Pr:

-

Prandtl number

- Q :

-

Internal heat source parameter

- Q 0 :

-

Internal heat source parameter

- Re:

-

Reynolds number

- T m :

-

Melting surface temperature (K)

- T s :

-

Solid medium temperature

- u, w :

-

Velocity along x and y directions (m/s)

- z :

-

Cylindrical coordinate in axial direction (m

- \(\left( {\rho C_{p} } \right)_{{{\text{nf}}}}\) :

-

Heat capacitance of nanofluid

- \(k_{{\text{f}}}\) :

-

Thermal conductivity of base fluid (W/mK)

- \(k_{{{\text{nf}}}}\) :

-

Thermal conductivity of nanofluid (W/mK)

- \(k_{{\text{s}}}\) :

-

Thermal conductivity of solid particle (W/mK)

- \(\rho_{{\text{f}}}\) :

-

Density of base fluid (kg/m3)

- \(\rho_{{{\text{nf}}}}\) :

-

Density of nanofluid (kg/m3)

- \(\rho_{{\text{s}}}\) :

-

Density of solid particle (kg/m3)

- \(\mu_{{\text{f}}}\) :

-

Dynamic viscosity of base fluid (kg/ms)

- \(\mu_{{{\text{nf}}}}\) :

-

Dynamic viscosity of nanofluid (kg/ms)

- \(\nu_{{{\text{nf}}}}\) :

-

Kinematic viscosity of nanofluid (kg/ms)

- \(\phi\) :

-

Solid volume fraction (%)

- \(\Lambda\) :

-

Porosity parameter

- \(\theta\) :

-

Non-dimensional temperature

- \(^{\prime }\) :

-

Derivative with respect to \(\eta\)

References

Choi, S.U.S., Eastman, J.A.: Enhancing thermal conductivity of fluids with nanoparticles. ASME Publ. Fed 231, 99–106 (1995)

Wang, C.Y.: Fluid flow due to a stretching cylinder. Phys. Fluids 31(3), 466–468 (1988)

Ishak, A., Nazar, R., Pop, I.: Uniform suction/blowing effect on flow and heat transfer due to a stretching cylinder. Appl. Math. Model. 32(10), 2059–2066 (2008)

Wang, C.Y., Ng, C.-O.: Slip flow due to a stretching cylinder. Int. J. Non Linear Mech. 46(9), 1191–1194 (2011)

Ashorynejad, H.R., Sheikholeslami, M., Pop, I., Ganji, D.D.: Nanofluid flow and heat transfer due to a stretching cylinder in the presence of magnetic field. Heat Mass Transf. 49(3), 427–436 (2013)

Majeed, A., Javed, T., Ghaffari, A., Rashidi, M.M.: Analysis of heat transfer due to stretching cylinder with partial slip and prescribed heat flux: A Chebyshev Spectral Newton Iterative Scheme. Alex. Eng. J. 54(4), 1029–1036 (2015)

Hayat, T., Shafiq, A., Alsaedi, A.: MHD axisymmetric flow of third grade fluid by a stretching cylinder. Alex. Eng. J. 54(2), 205–212 (2015)

Butt, A.S., Ali, A., Mehmood, A.: Numerical investigation of magnetic field effects on entropy generation in viscous flow over a stretching cylinder embedded in a porous medium. Energy 99, 237–249 (2016)

Pandey, A.K., Kumar, M.: Natural convection and thermal radiation influence on nanofluid flow over a stretching cylinder in a porous medium with viscous dissipation. Alex. Eng. J. 56(1), 55–62 (2017)

Pandey, A.K., Kumar, M.: Boundary layer flow and heat transfer analysis on Cu–water nanofluid flow over a stretching cylinder with slip. Alex. Eng. J. 56(4), 671–677 (2017)

Mishra, A., Pandey, A.K., Kumar, M.: Ohmic-viscous dissipation and slip effects on nanofluid flow over a stretching cylinder with suction/injection. Nanosci. Technol. Int. J. 9(2), 99–115 (2018)

Hayat, T., Ashraf, M.B., Shehzad, S.A., Bayomi, N.N.: Mixed convection flow of viscoelastic nanofluid over a stretching cylinder. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 37(3), 849–859 (2015)

Ebrahimi, A., Hosseini, M.J., Ranjbar, A.A., Rahimi, M., Bahrampoury, R.: Melting process investigation of phase change materials in a shell and tube heat exchanger enhanced with heat pipe. Renew. Energy 138, 378–394 (2019)

Khan, M., Malik, R.: Forced convective heat transfer to Sisko nanofluid past a stretching cylinder in the presence of variable thermal conductivity. J. Mol. Liq. 218, 1–7 (2016)

Khan, M., Malik, R.: Forced convective heat transfer to Sisko fluid flow past a stretching cylinder. AIP Adv. 5(12), 127202 (2015)

Malik, R., Khan, M., Mushtaq, M.: Cattaneo-Christov heat flux model for Sisko fluid flow past a permeable non-linearly stretching cylinder. J. Mol. Liq. 222, 430–434 (2016)

Ahmed, S.E., Hussein, A.K., Mohammed, H.A., Sivasankaran, S.: Boundary layer flow and heat transfer due to permeable stretching tube in the presence of heat source/sink utilizing nanofluids. Appl. Math. Comput. 238, 149–162 (2014)

Pandey, A.K., Kumar, M.: MHD flow inside a stretching/shrinking convergent/divergent channel with heat generation/absorption and viscous-Ohmic dissipation utilizing Cu−water nanofluid. Comput. Therm. Sci. Int. J. 10(5), 457–471 (2018)

Pandey, A.K., Kumar, M.: Effects of viscous dissipation and heat generation/absorption on nanofluid flow over an unsteady stretching surface with thermal radiation and thermophoresis. NanoscI. Technol. Int. J. 9(4), 325–341 (2018)

Singh, K., Kumar, M.: Melting and heat absorption effects in boundary layer stagnation-point flow towards a stretching sheet in a micropolar fluid. Ain Shams Eng. J. 9(4), 861–868 (2018)

Singh, K., Kumar, M.: Melting heat transfer in boundary layer stagnation point flow of MHD micro-polar fluid towards a stretching/shrinking surface. Jordan J. Mech. Ind. Eng. 8(6), 403–408 (2014)

Pandey, A.K., Kumar, M.: Effect of viscous dissipation and suction/injection on MHD nanofluid flow over a wedge with porous medium and slip. Alex. Eng. J. 55(4), 3115–3123 (2016)

Singh, K., Pandey, A.K., Kumar, M.: Analytical approach to stagnation-point flow and heat transfer of a micropolar fluid via a permeable shrinking sheet with slip and convective boundary conditions. Heat Transf. Res. 50(8), 739–756 (2019)

Hayat, T., Shafique, M., Tanveer, A., Alsaedi, A.: Magnetohydrodynamic effects on peristaltic flow of hyperbolic tangent nanofluid with slip conditions and Joule heating in an inclined channel. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 102, 54–63 (2016)

Hayat, T., Imtiaz, M., Alsaedi, A.: Melting heat transfer in the MHD flow of Cu–water nanofluid with viscous dissipation and Joule heating. Adv. Powder Technol. 27(4), 1301–1308 (2016)

Gangadhar, K., Ramana, K.V., Makinde, O.D., Kumar, B.R.: MHD flow of a Carreau fluid past a stretching cylinder with Cattaneo-Christov heat flux using spectral relaxation method. Defect Diffus. Forum 387, 91–105 (2018)

Das, S., Sensharma, A., Jana, R.N., Makinde, O.D.: Second-order slip flow of magneto-nanofluids along a stretching cylinder with prescribed heat flux. J. Nanofluids 6(4), 720–727 (2017)

Das, S., Chakraborty, S., Jana, R.N., Makinde, O.D.: Entropy analysis of unsteady magneto-nanofluid flow past accelerating stretching sheet with convective boundary condition. Appl. Math. Mech. 36(12), 1593–1610 (2015)

Khan, W.A., Makinde, O.D., Khan, Z.H.: Non-aligned MHD stagnation point flow of variable viscosity nanofluids past a stretching sheet with radiative heat. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 96, 525–534 (2016)

Ibrahim, W., Makinde, O.D.: Double-diffusive in mixed convection and MHD stagnation point flow of nanofluid over a stretching sheet. J. Nanofluids 4(1), 28–37 (2015)

Mishra, A., Pandey, A.K., Kumar, M.: Numerical investigation of heat transfer of MHD nanofluid over a vertical cone due to viscous-Ohmic dissipation and slip boundary conditions. Nanosci. Technol. Int. J. 10(2), 169–193 (2019)

Mishra, A., Pandey, A.K., Kumar, M.: Velocity, thermal and concentration slip effects on MHD silver–water nanofluid flow past a permeable cone with suction/injection and viscous-Ohmic dissipation. Heat Transf. Res. 50(14), 1351–1367 (2019)

Mishra, A., Pandey, A.K., Chamkha, A.J., Kumar, M.: Roles of nanoparticles and heat generation/absorption on MHD flow of Ag–H2O nanofluid via porous stretching/shrinking convergent/divergent channel. J. Egypt. Math. Soc. 28, 1–18 (2020)

Mishra, A., Pandey, A.K., Kumar, M.: Thermal performance of Ag–water nanofluid flow over a curved surface due to chemical reaction usingBuongiorno's model. Heat Transf. 50(1), 257–278 (2021)

Cebeci, T., Bradshaw, P.: Physical and Computational Aspects of Convective Heat Transfer. Springer, New York (1984)

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to convey their sincere gratitude to the reviewers for their precious comments and suggestions to improve the quality of this manuscript.

Funding

The authors declare that they have no funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KS carried out the problem design, computation and code validation. AKP was involved in methodology writing and draft preparation. MK guided throughout the draft preparation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Singh, K., Pandey, A.K. & Kumar, M. Melting heat transfer assessment on magnetic nanofluid flow past a porous stretching cylinder. J Egypt Math Soc 29, 1 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42787-020-00109-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s42787-020-00109-0