Abstract

Background

Captive rearing is often critical for animals that are vulnerable to extinction in the wild. However, few studies have investigated the extent to which captivity impacts hosts and their gut microbiota, despite mounting evidence indicating that host health is affected by gut microbes. We assessed the influence of captivity on the gut microbiome of the Brown Kiwi (Apteryx mantelli), a flightless bird endemic to New Zealand. We collected wild (n = 68) and captive (n = 38) kiwi feces at seven sites on the north island of New Zealand.

Results

Using bacterial 16 S rRNA and fungal ITS gene profiling, we found that captivity was a significant predictor of the kiwi gut bacterial and fungal communities. Captive samples had lower microbial diversity and different composition when compared to wild samples. History of coccidiosis, a gut parasite primarily affecting captive kiwi, showed a marginally significant effect.

Conclusions

Our findings demonstrate captivity’s potential to shape the Brown Kiwi gut microbiome, that warrant further investigation to elucidate the effects of these differences on health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Diet, behavior, habitat type, and environmental species pools can all influence the composition and diversity of gut microbiomes [1,2,3,4]. However, few studies have investigated the impact of captivity, a severe lifestyle shift, on avian gut microbiota. Reports on nine species of parrots, red-crowned crane (Grus japonensis), and vultures (Gyps fulvus and Neophron percnopterus) demonstrate that captivity can impact gut microbiomes [5,6,7]. Fewer studies have compared wild and captive gut bacteria and fungi across spatially distinct sites that vary by climate and vegetation [8], which are expected to differ in microbial species pools, a potential source for gut microbes.

Captive rearing is often necessary to conserve populations of threatened wildlife. In the case of the Brown Kiwi (Apteryx mantelli), predation from introduced mammals has made it imperative for some chicks to be raised in captivity until individuals are large enough to defend themselves [9]. Although successful in increasing population size, consequences to kiwi health via modification of the gut microbiome remain largely unknown. Factors pervasive in captivity such as artificial diets, sterilized built environments, human interaction, and medical intervention [10,11,12] may cause changes to the microbiome, but such changes remain undescribed.

Altering microbial communities may have costs to host health as microbes continue to be recognized for their roles in immune function, pathogen defense, and digestion [13]. Coccidiosis, a gut parasite caused by protozoan Eimeria spp., is a common disease in captive kiwi [14]. However, the relationship between captivity, coccidia, and gut microbial communities has garnered little attention. We sought to compare gut bacteria and fungi between captive and wild kiwi. We tested the hypothesis that captivity status and history of coccidiosis would decrease diversity and modify composition of the gut microbiome.

Results

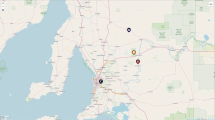

Fresh fecal samples were collected from seven sites on the north island of New Zealand (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Table 1) during January – April 2019.Bacterial 16 S rRNA (V4 region) [15] and fungal ITS genes [16] were amplified using DNA extracted from captive (n = 38) and wild kiwi fecal samples (n = 68). To ensure our findings were not an artefact of spatial autocorrelation, we conducted a Mantel test and found a weak association between the sites and the kiwi gut microbiome, however, it was not statistically significant (Mantel correlation, r = 0.138, p =0.308). PERMANOVA results (Supplementary Table 2) found a significant association of site in bacteria (r2 = 0.13, p = 0.001) and fungi (r2 = 0.183, p =0.001), which shows a relationship due to site but not necessarily due to spatial proximity. Kiwi eggs prior to captive rearing were lifted from five locations (Fig. 1a) that span the range of natural sites, indicating that captive lifestyle is more influential than geographic origin.

Captivity but not geography shifts the Brown Kiwi gut bacterial composition. A Map of collection sites and captive kiwi origin sites where shapes indicate type of site. Collection sites are locations where kiwi feces were sampled and origin sites are where kiwi eggs were lifted. Colors correspond to key in panel b. Teal colors correspond to captive sites, while brown colors correspond to wild sites. B NMDS plot using Bray-Curtis distance metric shows samples clustering by captivity status with little overlap between the groups (PERMANOVA, r2 = 0.07, p = 0.001). Ellipses denote 95 % confidence level

To determine whether captivity influences kiwi gut microbiota, we used PERMANOVA, linear models, and NMDS analyses. Bacterial communities clustered by captivity across spatially independent sites with little overlap between the 95 % confidence interval ellipses (Fig. 1b, PERMANOVA, r2 = 0.07, p = 0.001). We fitted separate linear models for bacteria and fungi, using log transformed principal coordinates axis 1 that explained 12.7 % of bacterial variation and 12.8 % of fungal variation, as a proxy for community composition, as our response variables. We found that captivity was a significant predictor of bacterial composition (r2 = 0.30, p < 0.001) but not fungal composition (r2 = 0.003, p = 0.301). Although bacterial phyla composition was variable within and across captivity status, Firmicutes was more prevalent in wild kiwi, while Proteobacteria dominated captive kiwi (Fig. 2b). Three fungal phyla, Ascomycota, Basidiomycota, and Mucoromycota, which contained nine classes were predominant in kiwi feces, and varied within and across captivity status (Supplementary Fig. 3).

The Brown Kiwi bacterial community differs both in diversity and composition due to captivity status. A Alpha diversity of captive kiwi is significantly reduced compared to wild individuals (linear model, r2 = 0.288, p < 0.001). B Relative abundances of bacterial phyla present at > 3 % between captive and wild kiwi. Vertical bars show the bacterial taxa and horizontal bars denote the collection site

Bacterial (Fig. 2a, ANOVA, p < 0.005) and fungal (Supplementary Fig. 1, ANOVA, p = 0.012) alpha diversity were significantly lower in captive kiwi by 33 and 74 % respectively. Using Shannon diversity (alpha diversity) as a response variable, we fitted a linear model to determine the relationship with captivity status and found captivity to be a significant predictor of bacterial (r2 = 0.288, p < 0.001) and fungal (r2 = 0.135, p = 0.012) alpha diversity. To assess the spread of variation among kiwi microbiomes in captive and wild conditions, we calculated distance to centroid, a metric for beta diversity. No discernible pattern was observed for bacteria (Supplementary Fig. 2a, ANOVA, p = 0.948), but a marginally significant pattern was detected in fungal communities where the mean value was higher in captive kiwi (Supplementary Fig. 2b, ANOVA, p = 0.051).

We also tested if site (a factor nested within captivity status) and history of coccidiosis (positive or negative) had an influence on variation in microbial communities using PERMANOVA (Supplementary Table 2). Site showed a significant effect on bacteria (r2 = 0.129, p = 0.001) and fungi (r2 = 0.183, p = 0.001). We ran a linear model using log transformed principal coordinates axis 1 as a proxy for community composition to test the influence of coccidiosis history, data only available for captive samples, on gut microbiota. We found a significant trend with bacteria (Supplementary Fig. 4, linear model, r2 = 0.118, p = 0.041) but not fungi (r2 = 0.043, p = 0.204). This contested our PERMANOVA findings which found a weak relationship that was not significant in bacteria (r2 = 0.048, p = 0.095) and fungi (r2 = 0.074, p = 0.087).

Using a multinomial species classification method (clamtest) [17], we categorized OTUs into four classes: rare, generalist, wild specialist, and captive specialist. For bacterial OTUs, 10 % were classed as generalist, 53 % as rare, 20 % as wild specialist, and 17 % as captive specialist (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Table 3). For fungal OTUs, 0 % were classed as generalist, 47 % as rare, 27 % as wild specialist, and 27 % as captive specialist (Fig. 3b, Supplementary Table 3). We conducted a simper analysis [17, 18] to determine the most influential OTUs that differentiate captive and wild kiwi samples for both bacteria and fungi. Thirteen bacterial OTUs and two fungal OTUs accounted for about 70 % of the differences between wild and captive samples (Supplementary Tables 4 and 5). Nine bacterial OTUs were more abundant in wild samples and five OTUs in captive kiwi (Fig. 3c). Two fungal OTUs were abundant only in wild kiwi (Fig. 3d).

Distinct microbial taxa are classed by their representation in captive and wild kiwi. A multinomial species classification method (clamtest) categorized bacterial and fungal OTUs into one of four classes: rare, generalist, wild specialist, and captive specialist. A For bacterial OTUs, 9.9 % were classed as generalist, 53 % as rare, 19.7 % as wild specialist, and 17.4 % as captive specialist. B For fungal OTUs, 0 % were classed as generalist, 46.7 % as rare, 26.7 % as wild specialist, and 26.7 % as captive specialist. Simper analysis detected several OTUs that explained 70 % difference between captive and wild kiwi. OTUs that were classed as either wild specialist or captive specialist in the clamtest were also represented in the same condition with simper. C Nine bacterial OTUs were significantly represented in wild kiwi and four bacterial OTUs in captive kiwi (FDR adjusted p < 0.05). D Two fungal OTUs were significantly represented in wild kiwi (FDR adjusted p < 0.05)

Discussion

Our results indicate that captivity explains bacterial and fungal community differences in the Brown Kiwi gut. Bacterial composition clustered by captivity (Fig. 1b), suggesting that kiwi from the wild are more similar to each other than their captive counterparts, even across geographically distinct sites. Bacterial and fungal alpha diversity were significantly lower in captive kiwi (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Fig. 1). The consequences of reduced microbial diversity between wild and captive kiwi remain unclear, but several studies have linked dysbiosis to higher disease prevalence in a variety of animals, including ostriches and chickens [19, 20]. Coccidiosis history, data only available for captive samples, showed a marginally significant effect (Supplementary Fig. 4). However, these results may be affected by small sample size. Our results suggest a potential link between differences in the microbiome to disease states that requires further exploration. Overall, our results suggest captivity simplifies the kiwi gut microbiome.

The shift in dominant bacterial phyla, Firmicutes to Proteobacteria, from wild to captive samples may be caused by microbially depauperate captive facilities, antibiotic treatment and post hoc probiotic supplementation. Frequent surface disinfection [11] and probiotic treatment [21] have been shown to increase Proteobacteria in human subjects. Lactobacillus (OTU 49), a common genus in probiotics, was grouped as a captive specialist and is overrepresented in captive kiwi (Fig. 3c). Other captive-associated taxa include Corynebacterium (OTU 62), which has been found in the cloaca of penguins and the preen gland of turkeys [22], and Bacteroides (OTU 544), normally found in animal hosts but can include potential pathogens [23]. Wild taxa such as, Ruminococcaceae (OTU 556) and Lachnospiraceae (OTU 570) (Fig. 3c), were overrepresented in wild kiwi. These two bacterial families were found in broiler chickens challenged with Clostridium perfringens [24], also a predominant wild taxa (OTU 13), suggesting a relationship between these taxa. Blautia (OTU 290), also common in wild kiwi, is a genus found in the human gut and associated with visceral fat accumulation [25]. Faecalitalea cylindroides (OTU 687), a butryrate producing microbe, has been detected in chicken [26]. These taxa may be indicative of nutrient acquisition in the wild, where food may be less available.

No fungal OTUs were categorized as generalists suggesting fungi in kiwi reflect their local environment. Some captive specialists include Cladosporium (OTU 151) and Aureobasidium (OTU 2), both associated with indoor environments and plant material [27, 28], implicating the contribution of soil and ferns added to enclosures. Trichosporon (OTU 171), another captive specialist, is a common human skin taxa [29], suggesting close human interaction may shape kiwi fungi. One wild specialist that is abundant in wild samples (Fig. 3d), Rhizopogon luteolus (OTU 159), has been identified as a dietary component of small mammals, suggesting kiwi may be consuming and dispersing these fungi [30]. Preussia (OTU 181) and Saitozyma podzolica (OTU 37), both associated with soil and litter, were grouped as wild specialists [31, 32].

Conclusions

In captivity, artificial diet, sterilized built environments, and human interaction are key factors that can shape gut microbial communities [10, 11]. Further detailed investigation of how gut microbes establish in developing kiwi chicks can elucidate how these factors inherent to captivity contribute to the kiwi gut microbiome. Overall, our data suggest that captivity explains differences in the gut microbiome of the Brown Kiwi with potential for health and disease assessment for captive-reared individuals.

Methods

Study system

Captive

Samples were collected (n = 38) from two captive sites (Fig. 1a). The National Kiwi Hatchery is located at the Rainbow Springs Nature Park in Rotorua, New Zealand. It is the leading facility in kiwi husbandry, egg incubation, and kiwi rearing. The facility has hatched and reared nearly 2000 kiwi eggs. Otorohanga Kiwi House is located in Otorohanga, New Zealand. Both facilities are a part of the Operation Nest Egg (ONE), a program in which kiwi eggs laid in the wild are transported to a hatchery and reared in a captive environment. Coccidiosis information was only available for the captive samples, where diagnosis is determined using a fecal flotation assay [33]. Kiwi were housed in brooder boxes – wooden boxes with soil, food, and water. Captive kiwi eat a diet mainly consisting of ox heart, cat biscuits, and rolled oats [34]. If positive for parasites or infections, individuals are administered antiprotozoal or antibiotic treatment. After antibiotics, kiwi are given probiotics that include a combination of Lactobacillus spp. and Bifidobacterium lactis.

Wild

Samples were collected (n = 68) from five natural sites with established wild kiwi populations (Fig. 1a). Ponui Island is located 30 km east of Auckland, New Zealand. 14 Brown Kiwi were introduced to the island by the New Zealand Wildlife Service in 1964, where populations have been increasing, establishing one of the densest populations of kiwi at an estimated 1500 individuals. Motuarohia Island is located in the Bay of Islands, 4 km northeast of Russell, New Zealand. Moturua Island is east of Motuarohia in the Bay of Islands. Puketi Forest is located in the Northland region of New Zealand. Rakaumangamanga is located near the Bay of Islands. These sites differ in climate and vegetation [8] and home to a number of Brown Kiwi individuals.

Sample collection

Fresh fecal samples (n = 108) were collected using sterile spatulas. Supplementary Table 1 details the quantity of samples collected per site. The interior of the fecal pellet was collected to ensure minimal environmental exposure. Due to the unique scent of kiwi excreta, we used the sample’s scent to confirm the feces was of kiwi origin [35]. Fecal samples were stored in 5 mL Eppendorf tubes suspended in molecular grade (100 %) ethanol and stored in -20ºC. DNA was extracted using MN NucleoSpin Soil Kit (Macherey-Nagel, Duren, Germany) on Janus extraction robot (PerkinElmer, Waltham, United States), suspended in TE buffer, and stored in -20ºC until PCR amplification.

Metabarcoding

We used a metabarcoding approach with a two-stage amplification process. During the first stage, we amplified the V4 region of the bacterial 16 S rRNA gene using 515 F/806R primers [15] and the fungal ITS gene [16]. The following PCR parameters were applied: denaturation at 95ºC for 2 min, followed by 35 cycles at 95ºC for 20 s, 50ºC for 20 s, and at 72ºC for 30 s, and final extension at 72ºC for 1 min. We used the resulting PCR products as template DNA in the second-stage PCR. Barcoded Fusion primers were used with the following PCR parameters: initial denaturation at 95ºC for 2 min, followed by 8 cycles of 95ºC for 20 s, 50ºC for 20 s, and 72ºC for 50 s, and final extension at 72ºC for 10 min [15]. We purified the second-stage PCR products using SeraMag magnetic beads to remove primer dimers and normalize concentration [36]. Qubit (dsDNA HS Assay Kit, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, United States) was used to quantify DNA concentration and libraries were diluted to 4 nM prior to final pooling. We pooled the libraries according to the concentration determined by Qubit, equimolar based on number of samples per library, and amplicon length. We used LabChip GX Touch Nucleic Acid Analyzer (PerkinElmer, Waltham, United States) to determine DNA concentration and assess quality of final pooled library. Samples were sequenced using Illumina MiSeq platform at Auckland Genomics Facility (University of Auckland), phiX spike 10 %, 250 × 2 cycles. Bioinformatics pipeline Claident was used to demultiplex raw sequences [37]. PEAR evaluated all possible paired-end read overlaps and merged sequences [38]. VSEARCH filtered noisy reads, removed chimeras, and clustered sequences into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) [39]. Claident clustered sequences into OTUs at 97 % similarity and assigned taxonomy with RDP classifier using the following databases, 16 S rRNA training set 16 (bacteria) and UNITE fungal ITS train set 07-04-2014 (fungi). Bioinformatic analysis were performed on the NeSI HPC environment.

Statistical analysis

We calculated Shannon diversity index (R package phyloseq version 2.5-7) [40] to test for a relationship between microbial alpha diversity and captivity. We calculated beta diversity using a multivariate version of Levene’s test for homogeneity of variances (betadisper in R package vegan version 2.5-7) [17]. We reported the distance to centroid value. To test for spatial autocorrelation among sites, we conducted a Mantel test (R package ade4 version 1.7–16) using microbiome data, and site location data (latitude and longitude) [41].

We used non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) with Bray-Curtis dissimilarity matrices to reduce multivariate data and spatially visualize microbial communities. NMDS was used to visualize clustering trends across captivity status. We used permutational analysis of the variance (PERMANOVA) also with Bray-Curtis distance matrices to determine whether different factors, such as captivity status (wild/captive), site (geographic area), microsite (i.e. in brooder box, soil, etc.), age (days old of captive individuals), weight (mass in grams for captive individuals), collection date, and history of coccidiosis (positive/negative) can explain microbial community variance. In addition, we ran linear models to determine whether captivity status or coccidiosis history were good predictors of both bacterial and fungal alpha diversity and community composition. We used Shannon Diversity Index values as a response variable for alpha diversity. In our community composition models, we used principal coordinates analysis axis values as our response variable. To fit the assumptions of the model and accommodate negative values, we added the minimum value plus one and log transformed the data. We ran a mixed effects model using site as a random effect, however, Akaike information criterion (AIC) and ANOVA confirmed that it did not improve the fit.

We used clamtest [17] to categorize bacterial and fungal OTUs into the following groups: generalist, too rare, and group specialist (wild-, captive-, positive-, negative-). Positive and negative correspond to individual kiwi who have had a history of coccidiosis. We conducted a simper analysis [17, 18] to determine which OTUs explain over 70 % of the differences between groups and to identify OTUs that are overrepresented.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in a github repository, https://github.com/psanjuan/kiwi_microbiome_2019.

Abbreviations

- OTU:

-

Operational taxonomic unit

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- DNA:

-

Deoxyribonucleic nucleic acid

- rRNA:

-

Ribosomal ribonucleic acid

- PERMANOVA:

-

Permutational analysis of the variance

- NMDS:

-

Non-metric multidimensional scaling

References

Hicks AL, Lee KJ, Couto-Rodriguez M, Patel J, Sinha R, Guo C, et al. Gut microbiomes of wild great apes fluctuate seasonally in response to diet. Nat Commun. 2018;9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-04204-w.

Ezenwa VO, Gerardo NM, Inouye DW, Medina M, Xavier JB. Animal Behavior and the Microbiome. Science(80-). 2012;338:198–9. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1227412.

San Juan PA. Land-use change has host-specific influences on avian gut microbiomes. ISME J. 2020;14:318–21.

Miller ET, Svanbäck R, Bohannan BJM. Microbiomes as metacommunities: understanding host-associated microbes through metacommunity ecology. Trends Ecol Evol. 2018;33:926–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2018.09.002.

Liu H, Chen Z, Gao G, Sun C, Li Y, Zhu Y. Characterization and comparison of gut microbiomes in nine species of parrots in captivity. Symbiosis. 2019;78:241–50.

Xie Y, Xia P, Wang H, Yu H, Giesy JP, Zhang Y, et al. Effects of captivity and artificial breeding on microbiota in feces of the red-crowned crane (Grus japonensis). Sci Rep. 2016;6:1–11.

Becker AAMJ, Harrison SWR, Whitehouse-Tedd G, Budd JA, Whitehouse-Tedd KM. Integrating Gut Bacterial Diversity and Captive Husbandry to Optimize Vulture Conservation. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:1–11.

Department of Conservation. https://www.doc.govt.nz/nature/habitats/. Accessed 29 Oct 2020.

Colbourne R, Bassett S, Billing T, McCormick H, McLennan J, Nelson A, et al. The development of Operation Nest Egg as a tool in the conservation management of kiwi. Sci Conserv. 2005;259:1–24.

Clayton JB, Vangay P, Huang H, Ward T, Hillmann BM, Al-Ghalith GA, et al. Captivity humanizes the primate microbiome. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2016;113:10376–81. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1521835113.

Mahnert A, Moissl-Eichinger C, Zojer M, Bogumil D, Mizrahi I, Rattei T, et al. Man-made microbial resistances in built environments. Nat Commun. 2019;10:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-08864-0.

Bokulich NA, Chung J, Battaglia T, Henderson N, Jay M, Li H, et al. Antibiotics, birth mode, and diet shape microbiome maturation during early life. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8:343ra82. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.aad7121.

Sommer F, Bäckhed F. The gut microbiota — masters of host development and physiology. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2013;11:227–38. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro2974.

Morgan KJ, Alley MR, Pomroy WE, Castro I, Howe L. Enteric coccidiosis in the brown kiwi (Apteryx mantelli). Parasitol Res. 2012;111:1689–99.

Caporaso JG, Lauber CL, Walters WA, Berg-Lyons D, Huntley J, Fierer N, et al. Ultra-high-throughput microbial community analysis on the Illumina HiSeq and MiSeq platforms. ISME J. 2012;6:1621–4.

Toju H, Tanabe AS, Yamamoto S, Sato H. High-coverage ITS primers for the DNA-based identification of ascomycetes and basidiomycetes in environmental samples. PLoS One. 2012;7:1–11.

Oksanen J, Blanchet F, Friendly M, Kindt R, Legendre P, McGlinn D. vegan: Community Ecology Package. R package version. 2017.

Steinberger A. seq-scripts release v. 1.1. 2020. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1458243.

Videvall E, Song SJ, Bensch HM, Strandh M, Engelbrecht A, Serfontein N, et al. Major shifts in gut microbiota during development and its relationship to growth in ostriches. 2019.

Kogut MH. The effect of microbiome modulation on the intestinal health of poultry. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 2019;250:32–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2018.10.008.

Ferrario C, Taverniti V, Milani C, Fiore W, Laureati M, De Noni I, et al. Modulation of fecal clostridiales bacteria and butyrate by probiotic intervention with Lactobacillus paracasei DG varies among healthy adults. J Nutr. 2014;144:1787–96.

Braun MS, Zimmermann S, Danner M, Rashid H, or, Wink M. Corynebacterium uropygiale sp. nov., isolated from the preen gland of Turkeys (Meleagris gallopavo). Syst Appl Microbiol. 2016;39:88–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.syapm.2015.12.001.

Grond K, Sandercock BK, Jumpponen A, Zeglin LH. The Avian Gut Microbiota: Community, Physiology and Function in Wild Birds. J Avian Biol. 2018;e01788:1–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/jav.01788.

Li Z, Wang W, Liu D, Guo Y. Effects of Lactobacillus acidophilus on gut microbiota composition in broilers challenged with Clostridium perfringens. PLoS One. 2017;12:1–16.

Ozato N, Saito S, Yamaguchi T, Katashima M, Tokuda I, Sawada K, et al. Blautia genus associated with visceral fat accumulation in adults 20–76 years of age. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes. 2019;5:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41522-019-0101-x.

De Maesschalck C, Van Immerseel F, Eeckhaut V, De Baere SD, Cnockaert M, Croubels S, et al. Faecalicoccus acidiformans gen. nov., Sp. nov., Isolated from the chicken caecum, And reclassification of streptococcus pleomorphus (barnes et al. 1977), Eubacterium biforme (eggerth 1935) and eubacterium cylindroides (cato et al. 1974). as faecalicoccus p. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2014;64:3877–84.

Bensch K, Groenewald JZ, Meijer M, Dijksterhuis J, Jurjević, Andersen B, et al. Cladosporium species in indoor environments. Stud Mycol. 2018;89:177–301.

van Nieuwenhuijzen EJ. Aureobasidium . Encycl Food Microbiol Second Ed. 2014;1:105–9.

Mariné M, Brown NA, Riaño-Pachón DM, Goldman GH. On and under the skin: emerging basidiomycetous yeast infections caused by trichosporon species. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:1–9.

Colgan W, Claridge AW. Mycorrhizal effectiveness of Rhizopogon spores recovered from faecal pellets of small forest-dwelling mammals. Mycol Res. 2002;106:314–20.

Arenal F, Platas G, Peláez F. Two new Preussia species defined based on morphological and molecular evidence Two new Preussia species defined based on morphological and molecular evidence Introduction species of bitunicate ascomycetes with non-ostiolate ascomata, containing dark. 2014.

Mašínová T, Bahnmann BD, Větrovský T, Tomšovský M, Merunková K, Baldrian P. Drivers of yeast community composition in the litter and soil of a temperate forest. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2017;93:1–10.

Coker SM, Pomroy WE, Howe L, McInnes K, Vallee E, Morgan KJ. Comparing the Mini-FLOTAC and centrifugal faecal flotation for the detection of coccidia (Eimeria spp.) in kiwi (Apteryx mantelli). Parasitol Res. 2020;119:4287–90.

Sales J. Feeding of the captive kiwi. Zoos’ Print J. 2006;21:2454–8. https://doi.org/10.11609/jott.zpj.1574b.2454-8.

Castro I, Cunningham SJ, Gsell AC, Jaffe K, Cabrera A, Liendo C. Olfaction in birds: a closer look at the kiwi (Apterygidae). J Avian Biol. 2010;41:213–8.

Rohland N, Reich D. Cost-effective, high-throughput DNA sequencing. Genome Res. 2011;22(5):939–46.

Tanabe AS, Toju H. Two New computational methods for universal DNA barcoding: a benchmark using barcode sequences of bacteria, archaea, animals, fungi, and land plants. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e76910.

Zhang J, Kobert K, Flouri T, Stamatakis A. PEAR: a fast and accurate Illumina Paired-End reAd mergeR. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:614–20.

Rognes T, Flouri T, Nichols B, Quince C, Mahé F. VSEARCH: a versatile open source tool for metagenomics. PeerJ. 2016;2016:1–22.

McMurdie PJ, Holmes S. Phyloseq: An R Package for Reproducible Interactive Analysis and Graphics of Microbiome Census Data. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e61217.

Dray S, Dufour AB. The ade4 package: implementing the duality diagram for ecologists. J Stat Softw. 2007;22:1–20.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ana Podolyan, Caroline Mitchell, Katherine Trought, Eva Weber, and Carina Davis at Manaaki Whenua Landcare Research for their expertise in the lab. Thank you to Malin Undin, Janneke Klute, Yi Luo, Emily Thompson, and Natasha Bansal for their help in field sampling. We appreciate the Chamberlain family for access to kiwi on their property. Ngai Tai (Ponui Island), Te Patukeha and Ngati Kuta (Rakaumangamanga, Moturua and Motuarohia) and Ngati Toro (Puketi) provided support and permission to collect fecal samples in their rohe (tribal areas) used in this study. Thank you to Emma Bean and Helen McCormick at the National Kiwi Hatchery and Ngāi Tahu for their continued support of the National Kiwi Hatchery and Jo Russell at the Otorohanga Kiwi House. Thank you to the Fukami Lab at Stanford University for their helpful feedback on the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Birds New Zealand grant for PASJ & MKD, MBIE Strategic Science Investment Fund supported MKD, the Royal Society of New Zealand Marsden Fund 17-MAU-154 and the Security for Iconic Species: Kiwi Rescue’ MBIE Programme 482 C09 × 1609 supporting IC, and the Stanford Center for Conservation Biology for PASJ. All captive research performed is covered under the Zoo and Aquarium Association of New Zealand permit and wild kiwi research is covered under the Department of Conservation permits 38796-FAU and 70826-CAP.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PASJ, MKD, and IC designed the study. PASJ and IC collected fecal samples. PASJ performed the molecular work including DNA extractions, PCR, and library preparation. PASJ and MKD completed the bioinformatics. PASJ conducted the statistical analyses. PASJ wrote the manuscript with feedback from MKD and IC. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Since animal handling was not required, no ethics approval was needed. However, all research conducted on captive and wild kiwi are covered under the Zoo and Aquarium Association of New Zealand permit and Department of Conservation permits 38796-FAU and 70826-CAP.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Supplementary Figure 1.

Fungal alpha diversity significantly decreases from wild to captive. Using Shannon’s diversity index, there is a 74.2% reduction in the average alpha diversity (ANOVA, p = 0.012) (linear model, r2 = 0.1348, p = 0.01233).

Additional file 2: Supplementary Figure 2.

Betadiversity of bacterial and fungal communities vary in their response to captivity. (A) There is no significant difference in betadiversity (distance to centroid) observed in bacteria (ANOVA, p = 0.948). (B) Fungal betadiversity shows a marginally significant trend with an increase in distance to centroid (ANOVA, p = 0.051). Distance to centroid was calculated using a multivariate version of the Levene’s test. Lower values indicate more shared microbial taxa among individuals of the same treatment. Higher values show higher microbial taxa variability among individuals of the same treatment.

Additional file 3: Supplementary Figure 3.

The Brown Kiwi fungal community is highly variable within and across groups. Relative abundances of fungi classes present at > 3% between captive and wild kiwi.

Additional file 4: Supplementary Figure 4.

History of coccidiosis influences kiwi gut bacteria. PCoA plot using Bray-Curtis distance metric shows samples clustering by coccidiosis history (PERMANOVA, r2 = 0.048, p = 0.095)(linear model, r2 = 0.1183, p= 0.041). Ellipses denote 95% confidence level.

Additional file 5: Supplementary Table 1.

Sample collection sites along with the latitude and longitude, captivity status, and sampling size.

Additional file 6: Supplementary Table 2.

Captivity influences bacterial and fungal communities. PERMANOVA results for different factors as predictors of microbial variance. Number of asterisks indicate level of statistical significance (***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05).

Additional file 7: Supplementary Table 3.

Clamtest categorizing bacterial and fungal OTUs found in wild and captive kiwi into rare, generalist, wild specialist, and captive specialist.

Additional file 8: Supplementary Table 4.

Most influential bacterial OTUs distinguishing between wild and captive kiwi samples listed by highest contributing OTU in descending order. Thirteen bacterial OTUs significantly account for over 70% of the differences between captivity status. OTUs that contributed to less than 1% significance was removed. A p-value was calculated per OTU, in addition to false discovery rate (FDR) adjusted p-value. Mean abundance and standard deviation of each OTU is listed between groups.

Additional file 9: Supplementary Table 5.

Most influential fungal OTUs distinguishing between wild and captive kiwi samples listed by highest contributing OTU in descending order. Two fungal OTUs significantly account for over 70% of the differences between captivity status. OTUs that contributed to less than 1% significance were removed. A p-value was calculated per OTU, in addition to false discovery rate (FDR) adjusted p-value. Mean abundance and standard deviation of each OTU is listed between groups.

Additional file 10: Supplementary Table 6.

Clamtest categorizing bacterial and fungal OTUs found in captive kiwi with and without a history of coccidiosis into rare, generalist, positive specialist, and negative specialist.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

San Juan, P.A., Castro, I. & Dhami, M.K. Captivity reduces diversity and shifts composition of the Brown Kiwi microbiome. anim microbiome 3, 48 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42523-021-00109-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s42523-021-00109-0