Abstract

Glycine-rich proteins (GRPs) have diverse amino acid sequences and are involved in a variety of biological processes. The role of GRPs in plant pathogenic fungi has not been reported. In this study, we identified and functionally characterized a novel gene named MoGRP1 in Magnaporthe oryzae, which encodes a protein that has an N-terminal RNA recognition motif (RRM) and a C-terminal glycine-rich domain with four Arg-Gly-Gly (RGG) repeats. Deletion of MoGRP1 resulted in dramatic reductions in fungal virulence, mycelial growth, and conidiation. The ΔMogrp1 mutants were also defective in cell wall integrity and in their responses to different stresses. MoGrp1 was localized to the nucleus and was co-immunoprecipitated with several components of the spliceosome, including subunits of the U1 snRNP and U2 snRNP complexes. Moreover, MoGrp1 exhibited binding affinity for poly(U). Importantly, MoGrp1 was responsible for the normal splicing of genes involved in infection-related morphogenesis. Domain deletion assays showed that both the RRM domain and its two adjacent RGG repeats were essential to the full function of MoGrp1. Notably, the nine amino acids between the first and the second RGG repeats were indispensable for nuclear localization and for the biological functions of MoGrp1. Taken together, our data suggest that MoGrp1 functions as a novel splicing factor with poly(U) binding activity to regulate fungal virulence, development, and stress responses in the rice blast fungus.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Glycine-rich proteins (GRPs) are a class of proteins containing glycine-rich domains in their primary structures. GRP-encoding genes are widely distributed in many eukaryotic species. The first glycine-rich protein to be identified, GRP-1, which was discovered in Petunia hybrida, has 384 amino acids in total, 252 of which are glycine residues (Condit and Meagher 1986). GRP-1 is a cell wall structural protein and is highly abundant in unexpanded tissues, especially in the buds (Condit et al. 1990). Glycine-rich proteins with glycine contents ranging from 20% to 70% in plants are diverse in their expression patterns, biological functions, and subcellular locations (Mangeon et al. 2010).

GRPs form a large superfamily and can be divided into four classes based on features of their protein sequences. Class I–III GRPs have typical signal peptides at the N-terminus but carry different motifs in their glycine-rich domains. Members of Class I GRPs have trailing repetitive (Gly-Gly-X)n domains. Most of these GRPs, such as GRP1 in petunia, are regarded as structural proteins due to their localization to cell walls. Class II GRPs have a glycine-rich domain consisting of the repetitive (Gly-Gly-XXX-Gly-Gly)n motif and a trailing cysteine-rich region at the C-terminus. Class III GRPs have the lowest glycine levels in comparison with GRPs of other classes. This class is characterized by a repetitive (Gly-X-Gly-X)n motif and wide structural diversity and usually contains oleosin domains.

In contrast, Class IV GRPs harbor nucleic acid-binding domains, most of which are RNA-binding domains. GRPs with both RNA recognition motifs (RRM) and glycine-rich domains usually contain repetitive (Arg-Gly-Gly)n motifs that facilitate RNA binding. The RRM in Class IV GRPs function in transcription and post-transcriptional modifications, thereby regulating multiple metabolic pathways, especially those related to stress resistance (Kupsch et al. 2012; Shi et al. 2016b). Glycine-rich domains in Class IV GRPs facilitate both the RNA-binding capacity and the protein–protein interactions, and increase the variability of RNA-binding proteins because of sequence specificity and structural disorder (Ciuzan et al. 2015). Several typical Class IV GRPs from human (Rbm3), Arabidopsis (AtGrp7), budding yeast (Npl3), and the human pathogen Candida albicans (Slr1) have been characterized. Rbm3 is expressed under hypothermic or hypoxemic conditions in humans (Al-Astal et al. 2016). The Atgrp7 mutants induce reduced Arabidopsis cold sensitivity (Kim et al. 2008). Npl3 plays a role in linking chromatin modification to mRNA processing and regulates the cold adaptation of budding yeast (Deka et al. 2008; Moehle et al. 2012). Slr1 is localized to the hyphal tips of C. albicans, and the deletion of Slr1 leads to defects in hyphal formation and function (Ariyachet et al. 2017). However, Class IV GRPs have not been reported in plant pathogenic fungi, and the role of GRPs in fungal pathogenesis remains to be investigated.

Rice blast, caused by the ascomycetous fungus Magnaporthe oryzae, is a devastating disease resulting in 10%–30% production loss in both rice and wheat crops (Hamer and Talbot 1998; Talbot and Foster 2001). This hemi-biotrophic pathogen is a model for the dissection of plant–fungal interactions and has a typical infection process involving appressorium-mediated penetration (Dean et al. 2012). The expression levels of genes involved in fungal infection-related morphogenesis and pathogenicity are regulated at transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels. Currently, hundreds of transcription factors (TFs) have been identified and functionally characterized in M. oryzae, such as bZIP-type TFs, C2H2-type TFs, and Zn2Cys6-type TFs (Lu et al. 2014; Kong et al. 2015; Cao et al. 2016). However, only a few studies have been reported on the post-transcriptional regulation of fungal pathogenicity and development. Rbp35 was the first protein identified in M. oryzae that controls mycelial growth, infection-related development, and pathogenicity through alternative processing of the 3′-end of the target pre-mRNAs (Franceschetti et al. 2011). Multilayer regulatory mechanisms are also found to control two fungal cleavage factor I (CFI) protein classes, the Rbp35/CfI25 complex and Hrp1 in M. oryzae (Rodríguez-Romero et al. 2015). In other phytopathogenic fungi, the role of the post-transcriptional gene control process has also been revealed. In the wheat head blight pathogen Fusarium graminearum, a serine/arginine-rich protein FgSrp1 was found to be necessary for plant infection and for pre-mRNA processing (Zhang et al. 2017), and that A-to-I RNA editing is important for ascosporogenesis (Liu et al. 2016, 2017). Protein kinase FgPrp4 is important for spliceosome B-complex activation and splicing efficiency and is required for fungal growth and pathogenicity as well (Gao et al. 2016). In the corn smut pathogen Ustilago maydis, two RNA-binding proteins, Khd4 and Rrm4, are required for fungal growth and virulence (Becht et al. 2005). It remains to be investigated whether and how other proteins that are involved in the post-transcriptional gene control process contribute to fungal pathogenicity and development.

In this study, we characterized the function of the gene MoGRP1, which encodes a glycine-rich RNA binding protein, and revealed that MoGrp1 is an auxiliary splicing factor unique to filamentous fungi that regulates virulence, development, and stress responses in the rice blast fungus.

Results

MoGRP1 is indispensable for hyphal growth, stress responses, and conidiation

In Magnaporthe oryzae, 65 genes were predicted to encode RRM proteins, which are thought to be involved in diverse cellular processes including DNA processing, mRNA processing, rRNA processing, RNA binding, and translation (Additional file 1: Table S1). To characterize the biological roles of these RRM proteins, we knocked-out several genes, and one of them, MGG_07511, was selected for further analysis in this study. MGG_07511 encodes a protein with 324 amino acids (aa) containing 53 glycines, an RRM domain (75–170 aa), and a glycine-rich domain with four Arg-Gly-Gly (RGG) repeats at its C-terminal region (Fig. 1a). Accordingly, we named this gene MoGRP1 (Glycine-Rich Protein 1) hereafter. Multiple sequence alignment of MoGrp1 homologs from over ten model eukaryotic species showed that the RRM domain was conserved, but that both the N- and C-terminal sequences, especially the region 175–324 aa, were only conserved among filamentous fungi and greatly divergent among other organisms (Fig. 1b and Additional file 2: Figure S1). Therefore, we proposed that MoGrp1 was a novel RNA-binding protein specific to filamentous fungi.

MoGrp1 is a novel RNA-binding protein that is specific to filamentous fungi and contains a glycine-rich domain. a Domain organization and amino acid sequence of MoGrp1. RRM, RNA recognition motif; RGG, Arg-Gly-Gly motif; RNP-1 and RNP-2, two highly conserved sequences of RRM; b High divergence in the C-terminal of MoGrp1 and its orthologous proteins (Additional file 2: Figure S1). Red box marks the high similarity region; blue arrows point to the divergent region (174 to 324 aa in MoGrp1). Conservation is shown by gradient color: highest in red and lowest in blue. The alignment was built using the MAFFT program and sequences were visualized in CLC Sequence Viewer

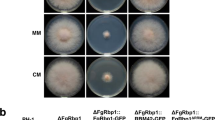

To study biological role of MoGRP1, the gene was deleted from a wild-type strain P131 by homologous recombination, and the resulting mutant, kg1, was confirmed by DNA gel blot analysis (Additional file 3: Figure S2). Growth assay showed that the rate of growth on complete medium (CM) of kg1 was only 4.84 ± 0.04 mm/day, much less than that of the wild-type strain (7.56 ± 0.02 mm/day) (Fig. 2a), suggesting a significant suppression of hyphal radial growth in the ΔMogrp1 mutant. Similar results were observed on oatmeal tomato agar (OTA) medium (Fig. 2a). In order to determine whether the growth inhibition was caused by nutrient limitation from the medium, strains P131 and kg1 were cultured on minimal medium (MM), nitrogen-free minimal medium (MM-N), and carbon-free minimal medium (MM-C). In comparison with the wild-type strain, strain kg1 exhibited similar growth reduction rates on MM and MM-N as on CM and OTA, whereas kg1 had about 10% higher growth reduction rate on MM-C (Fig. 2a, b), suggesting that the ΔMogrp1 mutant had a certain degree of carbon-dependence. These results imply that MoGRP1 is required for vegetative hyphal growth.

MoGRP1 is indispensable for hyphal growth, stress responses, and conidiation. a Mycelial growth of the wild-type strain P131, the ΔMogrp1 mutant kg1, and one ΔMogrp1 complementation transformant cg1g on CM, OTA, MM, MM-C, and MM-N plates at 28 °C for 5 days. The black circle indicates the extent of mycelia grown on MM-N and MM-C plates; b Column diagram showing colony diameter of strains cultured on different media in (a). The mean ± SD was calculated based on three independent experiments measuring three plates in each replicate. An asterisk marks significant differences among strains according to a T-test (P < 0.05); c Conidiation structures of strains P131, kg1, and cg1g cultured on OTA plates. Bar, 30 μm; d Conidiation capacity of strains P131, kg1, and cg1g cultured on OTA plates. The mean ± SD was calculated based on three independent experiments measuring three plates in each replicate. *P < 0.05; e Conidial morphology of strains P131, kg1, and cg1g. Bar, 20 μm; f Percentage of conidia with 0-, 1-, and 2- septa of strains P131, kg1, and cg1g. The mean ± SD was calculated based on three independent experiments measuring at least 100 conidia in each replicate. *P < 0.05

Previous studies have suggested that GRPs are usually involved in stress responses, such as those provoked by cell wall-perturbing agents and H2O2 (Schmidt et al. 2010; Wang et al. 2013). Accordingly, we tested whether strain kg1 was also sensitive to different stresses by incubating it on CM plates supplemented with different stress chemicals. Compared to the CM control, growth inhibition rates of the kg1 colonies were 68.3%, 18.3%, 38.1%, and 64.3% on 200 μg/mL Calcofluor White (CFW), 200 μg/mL Congo Red (CR), 0.025% SDS solution, and 10 mM H2O2, respectively, which were higher than those exhibited by the wild-type strain (Table 1). In contrast, strain kg1 exhibited similar growth inhibition rates as the wild type on 1 M sorbitol, 0.7 M NaCl, and 5 mM CuSO4 (Additional file 1: Table S2). Moreover, strain kg1 was more sensitive to abnormal temperature. The growth inhibition rates of kg1 were 13.7% and 14.4% higher than that of the wild-type P131 when cultured on OTA plates at 34 °C and 18 °C, respectively (Table 1). Hydrophobicity of fungal hyphae was also tested by placing water or 0.2% SDS droplets onto colonies formed on OTA plates (Breth et al. 2013). Both strain P131 and kg1 formed intact droplets on their hyphae, whereas kg1 but not P131 was wettable by 0.2% SDS (Additional file 4: Figure S3), suggesting that strain kg1 showed a partial loss of hydrophobicity. These results suggest that MoGRP1 may play important roles under different stresses.

To evaluate the effect of MoGRP1 on conidiogenesis, conidial production of strains P131 and kg1 was compared on OTA plates. While the wild-type P131 generated 3–5 conidia per conidiophore, strain kg1 produced just 0–1 conidia per conidiophore (Fig. 2c). As a result, the number of conidia produced by strain kg1 on each OTA plate was only about 5% of the wild-type strain (Fig. 2d). Moreover, about 70% of the kg1 conidia were abnormal with 0–1 septum and a lemon-shaped morphology, whereas the wild-type conidia had two septa with a pyriform shape (Fig. 2e, f). All of the above defects of the ΔMogrp1 mutant in hyphal growth, stress responses, and conidiation could be rescued by expressing a wild-type MoGRP1 allele in strain kg1, including a complementation strain cg1g (Fig. 2). These observations indicate that MoGRP1 is required for maintaining normal conidiation and conidial morphology.

MoGRP1 is required for plant infection and infection-related morphogenesis

To determine roles of MoGRP1 in plant infection, conidial suspensions of strains P131, kg1, and cg1g were sprayed onto seedlings of rice and barley. While strains P131 and cg1g formed numerous typical disease lesions on rice leaves, kg1 produced few and limited disease spots (Fig. 3a). Similar results were obtained on barley leaves (Fig. 3a). Moreover, kg1 only caused very limited disease lesions on abraded rice leaves after inoculation with mycelial plugs (Fig. 3a). Hence, MoGRP1 played vital roles in infection and the extension of invasive hyphae in plant tissues.

MoGRP1 is required for plant infection and infection-related morphogenesis. a Disease lesions formed on rice seedlings (left panel), barley seedlings (middle panel), and abraded rice leaves (right panel) by inoculation of the wild-type strain P131, the ΔMogrp1 mutant kg1, and one ΔMogrp1 complementation transformant cg1g. Typical disease lesions were photographed at 5–7 dpi; b Appressorium formation on glass coverslips (upper panel) and its percentages (lower panel) by strains P131, kg1, and cg1g at 12 hpi. The mean ± SD was calculated based on three independent experiments measuring at least 100 germinated conidia in each replicate. Bar, 20 μm. *P < 0.05; c Appressorium-mediated penetration and invasive hyphal development in epidermal cells of barley leaves by strains P131, kg1, and cg1g at 24, 36, and 48 hpi. Bar, 20 μm; d Column diagram showing the percentage of penetration pegs forming invasive hyphae in the epidermal cells of barley leaves by strains P131, kg1, and cg1g at 24 hpi. The mean ± SD was calculated based on three independent experiments measuring at least 100 appressoria in each replicate. *P < 0.05; e Column diagram showing the percentage of invasive hyphae extending into neighboring cells in the epidermis of barley leaves by strains P131, kg1, and cg1g at 48 hpi. The mean ± SD was calculated based on three independent experiments measuring at least 60 infection sites in each replicate. *P < 0.05

Infection-related morphogenesis was then investigated. At 12 hours post inoculation (hpi), approximately 5% of the kg1 conidia formed appressoria on hydrophobic surfaces, compared with about 90% of the wild-type conidia (Fig. 3b). At 36 hpi, the wild-type invasive hyphae were well developed and formed over five bulbous branches, but fewer than 20% of the kg1 appressoria penetrated into barley epidermal cells and developed few and limited branches (Fig. 3c, d). At 48 hpi, over 80% of the wild-type invasive hyphae had spread into neighbouring cells, whereas no invasive hyphae was observed in neighbouring cells for kg1 strain (Fig. 3c, e). Taken together, these findings suggest that MoGRP1 is required for appressorium formation, appressorial penetration, and the development of invasive hyphae, which contribute significantly to fungal virulence.

MoGrp1 is localized to the nucleus and is constitutively expressed

To determine the subcellular localization of MoGrp1, a construct expressing a MoGrp1-GFP fusion protein driven by the RP27 promoter was generated and introduced into strain kg1. Fifteen independent transformants were obtained and all of which recovered defects of strain kg1, suggesting that the MoGrp1-GFP fusion was functional. Strong and clear nuclear localization of green fluorescent signals were observed in the conidia, appressoria, and invasive hyphae of the transformants, including cg1g (Fig. 4a). The expression levels of MoGRP1 were examined by quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR). Wild-type samples were prepared from vegetative hyphae, conidia, appressoria, and infected barley leaves (Chen et al. 2017). MoGRP1 was widely expressed among these samples, among which the conidia exhibited the highest expression level (Fig. 4b).

MoGrp1 is localized to nuclei and binds to poly(U) RNA. a MoGrp1 is localized to nuclei of conidia, appressoria, and infection hyphae of strain cg1g expressing a MoGrp1-GFP fusion protein. Bar, 20 μm; b Relative expression levels of MoGRP1 in mycelia (My), conidium (Co), mature appressorium (Ap12h), and invasive hyphae (IH24h and IH42h) measured by quantitative RT-PCR. The expression level of MoGRP1 was first normalized with the actin gene in each tested tissue, and the expression level of MoGRP1 was set to 1. The means and standard deviations were calculated based on two independent experiments with three replicates; c The 3 × Flag-MoGrp1 or 3 × Flag-MoGrp1ΔRNP-2 constructs bind to different types of biotinylated nucleic acids, including poly(U)30, poly(A)30, single-strand DNA (ssDNA), and double-strand DNA (dsDNA). The 3 × Flag-tagged protein was immunoprecipitated from strain cg1f expressing the 3 × Flag-MoGrp1 fusion protein or strain cg1fdR expressing the 3 × Flag- MoGrp1ΔRNP-2 fusion protein. (−) is a negative control, showing that beads cannot bind target proteins without biotinylated nucleic acids

MoGrp1 preferentially binds to poly(U) RNA

Because MoGrp1 contains a conserved RRM domain, we hypothesized that it might bind to a subclass of nucleic acids. To test the category of its binding targets, MoGrp1 was first purified by anti-Flag M2 affinity beads from strain cg1f expressing the 3 × FLAG-MoGRP1 fusion construct in the ΔMogrp1 mutant kg1. The strain cg1f exhibited the wild-type phenotype in asexual development and plant infection. The purified 3 × Flag-MoGrp1 was then co-incubated with several artificially synthesized nucleic acids, i.e., biotinylated poly(A)30 and poly(U)30 RNAs and single- and double-stranded calf-thymus DNA. The resulting mixtures were immunoprecipitated by streptavidin and detected by an anti-FLAG antibody in the corresponding elutions. Among the four tested targets, poly(U)30 RNA exhibited the strongest binding capacity to MoGrp1, while poly(A)30 RNA had a weak binding capacity to MoGrp1. In contrast, the binding capacity to MoGrp1 was not detected for either of the single- and double-stranded calf-thymus DNA. Moreover, when the RNP-2 motif (RGFGFVK, 119–125 aa) of the RRM domain was removed from MoGrp1, the resulting truncated MoGrp1 (dRRM) was not able to bind any of the four tested targets. These findings suggest that MoGrp1 preferentially binds to poly(U) RNAs, and the RRM domain is essential for its RNA-binding capability (Fig. 4c).

MoGrp1 interacts with components of the spliceosome

The proteins co-purified with MoGrp1 were isolated by affinity protein purification approach using strain cg1f expressing 3 × Flag-MoGrp1. Seven potential MoGrp1 co-immunoprecipitated proteins were identified by LC-MS/MS analysis, including U2 snRNP complex subunits MoRse1 and MoIst3, U1snRNP complex subunits MoPrp40 and MoLuc7, RNA-binding protein MoRbm25, and H/ACA RNP complex subunit 1 and 2 (Fig. 5a). To confirm the interaction between MoGrp1 and MoRse1, the strain CoFG9 co-expressing 3 × Flag-MoGrp1 and MoRse1-GFP were generated, and then the 3 × Flag-MoGrp1 protein was precipitated from the total proteins by anti-FLAG immunoprecipitation. The MoRse1-GFP protein could be detected with an anti-GFP antibody in both the elution sample and the total protein extract (Fig. 5b), indicating that MoGrp1 interacted with MoRse1-GFP in vivo. Similarly, MoGrp1 was co-immunoprecipitated with MoGar1 in vivo (Fig. 5c). However, yeast two-hybrid assays failed to reveal the interactions between MoGrp1 and the two individual splicing factors (data not shown). Taken together, these results indicate that MoGrp1 can be co-immunoprecipitated with components of the spliceosome and therefore might function as an auxiliary splicing factor.

MoGrp1 can be co-immunoprecipitated with components of the spliceosome. a List of proteins co-immunoprecipitated with 3 × Flag-MoGrp1; b Immunoblot of the total protein (input) and those eluted from anti-FLAG M2 beads (elution) of strain CoFG9 expressing both the MoRse1-GFP fusion protein and the 3 × Flag-MoGrp1 fusion protein. Strain eRse1 expressing the MoRse1-GFP fusion was used as control. The MoRse1-GFP fusion protein and the 3 × Flag-MoGrp1 fusion protein were probed with an anti-GFP antibody and an anti-Flag antibody, respectively; c Immunoblot of the total protein (input) and those eluted from anti-FLAG M2 beads (elution) of strain CoFG1 expressing both the MoGar1-GFP fusion and the 3 × Flag-MoGrp1 fusion. Strain eGar1 expressing the MoGar1-GFP fusion was used as control. The MoGar1-GFP and the 3 × Flag-MoGrp1 fusion proteins were probed with an anti-GFP antibody and an anti-Flag antibody, respectively

MoGrp1 is necessary for normal splicing of genes involved in infection-related morphogenesis

To test whether MoGrp1 contributes to intron splicing, two genes, MST7 and MoRAD6, which are important to fungal growth, conidiation, and pathogenicity in M. oryzae (Zhao et al. 2005; Shi et al. 2016a), were selected for analysis. The intron splicing efficiency was evaluated by RT-PCR with a pair of primers amplifying the intron region. As shown in Fig. 6, obvious intron retentions occurred in the transcripts of MST7 and MoRAD6 from the ΔMogrp1 mutant kg1 in comparison to those from the wild-type strain P131. Amplified genomic DNA was used as the un-spliced control. Therefore, MoGrp1 plays important roles in intron splicing, at least for genes related to fungal development and pathogenicity.

MoGrp1 is necessary for normal splicing of genes involved in infection-related morphogenesis. RT-PCR analysis on selected introns (marked with a star) of MoRAD6 and MST7, which were abnormally spliced in the ΔMogrp1 mutant kg1 in comparison with the wild-type strain P131. The amplified genomic DNA was used as the un-spliced control. The transcripts are presented with exons in black rectangles, UTRs in grey rectangles, and introns indicated by black lines. The PCR primers are marked with arrows

Both the RRM and RGG motifs of MoGrp1 are indispensable for fungal development and plant infection

To dissect biological roles of different motifs in MoGrp1, four constructs expressing truncated MoGrp1 proteins fused with GFP at the C-terminal were generated (Fig. 7a) and introduced into the ΔMogrp1 mutant kg1. For each construct, at least 10 independent transformants were selected for analyses of plant infection, colony growth, and conidiation (Fig. 7b-d). Transformants expressing the wild-type MoGRP1 in strain kg1 exhibited wild-type phenotypes and were used as a positive control. Firstly, using the strain dN with deletion of its N-terminal region (1–74 aa), we demonstrated that the N-terminal before the RRM was not necessary for the function of MoGrp1. In contrast, the truncated dRRM strain in which the RNP2 motif was deleted could not rescue any defects of strain kg1, suggesting that the RNP2 motif is essential to the function of MoGrp1. Furthermore, while strain Δ265–324, in which the C-terminal region (from the 3rd RGG motif to the end, 265–324 aa) was deleted, could rescue all defects of strain kg1, strain Δ182–324, in which most of the glycine-rich domain (from the 1st RGG motif to the end, 182–324 aa) was deleted, could not rescue any defects of strain kg1. These findings suggested that the N-terminus of the glycine-rich domain with the first two RGG motifs is indispensable to MoGrp1. Interestingly, strain Δ191–324, in which most of the glycine-rich domain (from the 2nd RGG motif to the end, 191–324 aa) was deleted, could not fully rescue the defects of strain kg1, suggesting that the 9-aa fragment (RGGRFDDRR, 182–190 aa) contributed greatly to the function of MoGrp1. Lastly, the strain Δ182–190, in which the 9-aa fragment (RGGRFDDRR, 182–190 aa) was deleted, was not able to rescue the defects of strain kg1. Moreover, the AGG mutant (R182A and R191A) showed that arginine methylation in RGG was not important for MoGrp1. Taken together, these results indicate that both the RRM domain and N-terminal region of the glycine-rich domain with the first two RGG motifs were essential for the function of MoGrp1.

Both the RRM and the first two RGG motifs are essential for the full function of MoGrp1. a Structure diagram of N-terminal 3 × Flag tagged MoGrp1 (cg1f), C-terminal GFP tagged MoGrp1 (cg1g) and their mutated alleles, including RNP-2 deletion (dRRM, MoGrp1Δ119–125), N-terminal deletion (dN, MoGrp1Δ1–74), glycine-rich domain complement transformant (dNR, MoGrp1Δ1–173), deletion from the 3rd RGG motif to the end (Δ265–324, MoGrp1Δ265–324), deletion from the 2nd RGG motif to the end (Δ191–324, MoGrp1Δ191–324), deletion from the 1st RGG motif to the end (Δ182–324, MoGrp1Δ182–324), deletion from 182 to 190 aa (Δ182–190, MoGrp1Δ182–190), transformant containing RRM and 1st RGG (dNG, MoGrp175–190), and AGG mutant (AGG, MoGrp1R182A, R191A); b Pathogenicity test of diverse domain-complemented strains in rice seedlings. Typical disease lesions were photographed at 5–7 dpi; c Colony diameter of diverse domain-complemented strains on OTA plates at 28 °C for 5 days. The mean ± SD was calculated based on three independent experiments measuring three plates in each replicate. *P < 0.05; d Conidiation capacity of diverse domain-complemented strains on OTA plates. The mean ± SD was calculated based on three independent experiments with measuring three plates in each replicate. *P < 0.05

The fragment RGGRFDDRR is essential for the nuclear localization of MoGrp1

To determine the sequence responsible for the nuclear localization of MoGrp1, all of the aforementioned transformants were stained by DAPI and observed under a microscope. Strong green fluorescence signals, localized to the nuclei, were observed in transformants expressing the entire glycine-rich domain (182–324 aa) or the truncated MoGrp1Δ265–324 domain, whereas only cytoplasmic localized green fluorescence signals were found in transformants expressing the truncated MoGrp1△182–324 domain (Fig. 8). Interestingly, both nuclear and cytoplasmic green fluorescence signals were detected in transformants expressing the truncated MoGrp1△191–324 domain or the dNG domain with the RRM and the 182–190 aa (Fig. 8). These findings suggest that the 9 aa fragment, RGGRFDDRR (182–190 aa), was required for the nuclear localization of MoGrp1, which in turn was associated with the biological role of MoGrp1 in fungal development and virulence.

The sequence between the 1st and 2nd RGG is essential to nuclear localization of MoGrp1. Subcellular localization of the C-terminal GFP tagged MoGrp1 (cg1g) construct and its mutated alleles dNR (MoGrp1Δ1–173), Δ265–324 (MoGrp1Δ265–324), Δ191–324 (MoGrp1Δ191–324), Δ182–324 (MoGrp1Δ182–324), Δ182–190 (MoGrp1Δ182–190), dNG (MoGrp175–190), and AGG (MoGrp1R182A, R191A) in conidia of the ΔMogrp1 mutant kg1. Bar, 10 μm

Discussion

In this study, we characterized the function of a novel gene MoGRP1 from M. oryzae, which encodes a glycine-rich RNA-binding protein with four RGG repeats. The MoGRP1 deletion mutants showed deficiency in a wide range of biological processes including vegetative hyphal growth, stress responses, conidiogenesis, appressorial function, invasive hyphal growth, and virulence. These results suggest that the loss-of-function of MoGrp1 may lead to widespread effects because of its potential roles in RNA binding and pre-mRNA splicing. Moreover, bioinformatics analysis reveals that MoGrp1 was unique to filamentous fungi. Another RNA-binding protein Rbp35 with an N-terminal RRM and six RGG repeats has been reported to be involved in alternative pre-mRNA 3′-end processing and required for full fungal virulence and development of M. oryzae (Franceschetti et al. 2011). Interestingly, homologs of Rbp35 are found in many filamentous fungi, but are absent in yeast, plants, or animals, suggesting that Rbp35 is restricted to filamentous fungi. Accordingly, we speculate that filamentous fungi may contain many other similar RNA-binding proteins that control fungal development and pathogenicity (Vollmeister et al. 2009). In U. maydis, among 18 RNA-binding proteins, Khd4 and Rrm4 were found to be required for fungal growth and virulence, and Khd1 contributed to cold-sensitive growth (Becht et al. 2005). This suggests that some, but not all RNA-binding proteins, play major roles in fungal development and pathogenicity. Recently, J-R Xu’s group reported that a serine/arginine-rich protein FgSrp1 and a protein kinase FgPrp4, both of which participate in pre-mRNA splicing, are required for fungal growth and pathogenicity in F. graminearum (Gao et al. 2016; Zhang et al. 2017). They also found that A-to-I RNA editing is important for fungal ascosporogenesis (Liu et al. 2016, 2017). These findings illustrated that post-transcriptional gene control processes play vital roles in fungal pathogenicity and development. It will be interesting and challenging to identify the inventory of proteins that are involved in the post-transcriptional gene control processes, which contribute to fungal pathogenicity and development.

Our results showed that MoGrp1 was localized to nuclei, and that it was able to be co-immunoprecipitated with several components of the spliceosome, including subunits of the U1 snRNP and U2 snRNP complexes, MoRse1, and MoGar1. MoRse1 is a component of the pre-spliceosome and is involved in pre-mRNA splicing. It associates with U2 snRNA (Chen et al. 1998; Caspary et al. 1999). MoGar1 is a core component of the H/ACA ribonucleoprotein pseudouridylase complex and is involved in the modification and cleavage of 18S pre-rRNA (Bousquet-Antonelli et al. 1997; Tremblay et al. 2002; Li and Ye 2006). Our findings suggest that MoGrp1 might be an auxiliary component of the pre-spliceosome A complex, in which U1 snRNP binds to a 5′ splicing site (5’SS) and U2 snRNP binds to the branch-point sequence (Wahl et al. 2009). However, we did not detect direct interactions between MoGrp1 and these two splicing factors in the yeast two-hybrid assays, implying that other component(s) of the spliceosome may be necessary for the physical interactions. Similar phenomenon has been described often in multiple-subunit complexes, including in the spliceosome (Hegele et al. 2012). Moreover, MoGrp1 possessed a strong binding affinity for poly(U) RNAs, but bound weakly to poly(A) RNAs and not to ssDNAs or dsDNAs. Currently we are unable to obtain poly(C) and poly(G) RNAs and have not assessed binding capacities of these two homopolymer RNAs to MoGrp1. Thus, our data support the hypothesis that MoGrp1 is at least a poly(U) RNA-binding protein.

Based on our findings that MoGrp1 co-immunoprecipitates with the pre-spliceosome A complex and has strong binding affinity for poly(U) RNA, we speculated that MoGrp1 may play a role in regulating splicing by two possible mechanisms. Firstly, MoGrp1 may be involved in splice site selection. In higher eukaryotes where alternative splicing is prevalent, and because most splice site consensus sequences are relatively degenerate and splice sites alone are not capable of efficiently directing spliceosome assembly, recognition and selection of splice sites is influenced by flanking pre-mRNA regulatory sequences in most cases (Cartegni et al. 2002; Singh and Valcárcel 2005; Wahl et al. 2009). In human and mouse cells, poly(U)-rich sequences in exons near 5’SS were demonstrated to function as splicing enhancers and play important roles in splice site selection (Tanaka et al. 1994; Wongpalee et al. 2016). Secondly, MoGrp1 may contribute to exon inclusion. In human and mouse cells, poly(U)-rich sequences in introns downstream of 5’SS were found to promote exon inclusion and to be regulated by the cytotoxic granule-associated RNA-binding proteins TIA1 and TIA1-like 1 (TIAL1) (Aznarez et al. 2008). TIA1/TIAL1 function by binding to intron poly(U)-rich sequences immediately downstream from 5’SS in a U1 snRNP-dependent fashion (Del Gatto-Konczak et al. 2000). Although we currently do not have a clear picture on how MoGrp1 functions during the early process of intron splicing, its molecular mechanism might be better illustrated by RNA immunoprecipitation and RNA-sequencing approaches, which can identify the potential MoGrp1-binding sequences and motifs in targeting pre-mRNAs.

Proteins with single or multiple RGG motifs are usually core components of many mRNA process-related complexes and interact with RNAs and proteins participating in diverse cellular processes, such as transcription, splicing, mRNA export, nucleo-cytoplasmic shuttling, and post-translational modification (Nichols et al. 2000; Brahms et al. 2001; McBride et al. 2005; Peng et al. 2006; Wong et al. 2010; Rajyaguru and Parker 2012; Rodríguez-Romero et al. 2015). For example, the RNA-binding protein Icp27 of the herpes simplex virus shows low RNA-binding activity and intron retention reduction without its RGG motif (Mears and Rice 1996; Tang et al. 2016). The RGG domain of Rbp16 in Trypanosoma brucei can individually bind RNA (Miller and Read 2003). The RGG domain of Rbp35 in M. oryzae regulates cleavage efficiency and the localization and degradation processes of Rbp35 itself (Rodríguez-Romero et al. 2015). In our study, it is not certain whether the sequence containing RGG repeats in MoGrp1 has RNA-binding capacity, but the sequence between the first and the second RGG repeats (a 9-aa fragment, RGGRFDDRR) was demonstrated to be essential for the biological function and nuclear localization of MoGrp1. These findings suggest that the 9-aa fragment RGGRFDDRR can guide MoGrp1 into nuclei, and that nuclear localization of MoGrp1 is indispensable for its biological function. By using PSORT II prediction, a nuclear localization signal sequence (27–57 aa) was predicted at the N-terminal region before the RRM domain of MoGrp1, but this sequence was found to be dispensable for the nuclear localization of MoGrp1. A similar phenomenon has been observed in maize with RNA-binding protein MA16 and its interaction protein ZmDRH1, as the region containing the RGG motifs in both of these two proteins is necessary for their nuclear/nucleolar localization (Gendra et al. 2004). Therefore, it will be interesting to identify MoGrp1-interacting proteins by using the domain deletion alleles generated in our study, which may further illustrate how MoGrp1 is translocated into nuclei from the cytoplasm, and promote the understanding of how MoGrp1 is involved in pathogenicity, development, and stress responses in the rice blast fungus.

Conclusions

In this study, we functionally characterized a glycine-rich RNA-binding protein encoded by the MoGRP1 gene in M. oryzae. MoGRP1 encodes a filamentous fungi-unique Class IV glycine-rich protein, which contains an N-terminal RRM domain and a C-terminal glycine-rich domain with four RGG tri-peptide repeats. MoGRP1 is important for fungal virulence, asexual growth and development, and responses to different stresses. MoGrp1 is localized to nuclei and can be co-immunoprecipitated with components of the spliceosome, including several subunits of the U1 snRNP and U2 snRNP complexes. Moreover, MoGrp1 possesses a high binding affinity for poly(U). Importantly, MoGrp1 is responsible for the normal splicing of genes involved in infection-related morphogenesis. Domain deletion assays showed that the nine amino acids between the first two RGG repeats were essential for both the nuclear localization and biological functions of MoGrp1. Taken together, MoGrp1 functions as a novel splicing factor unique to filamentous fungi and regulates fungal virulence, development, and stress responses in the rice blast fungus.

Methods

Fungal strains and culture conditions

The wild-type M. oryzae field strain P131 was used for molecular and pathogenicity assays. P131 and its derivative transformants (Additional file 1: Table S3) were cultured on oatmeal tomato agar (OTA), complete medium (CM), or minimal medium (MM) plates (Peng and Shishiyama 1988; Talbot 2003). Fungal growth was assayed after incubation at 28 °C for 5 days on CM plates with 0.7 M NaCl, 1 M sorbitol (Amresco, USA), 5 mM CuSO4, 200 μg/mL Congo red (Sigma, USA), 200 μg/mL Calcofluor white (Sigma, USA), 0.025% SDS, or 10 mM H2O2 to test sensitivities to various stresses and after incubation at 18 °C or 34 °C on CM as described (Kong et al. 2012). Conidiation assays were performed as previously described (Wang et al. 2016).

Nucleic acid manipulation

Genomic DNA was extracted from vegetative mycelia using the cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) protocol (Xu and Hamer 1996). Plasmid isolation, nucleic acid extraction, DNA gel blots, enzymatic manipulation, and sequencing were performed as described by Sambrook and Russell (2001). Probes for DNA blotting were labeled with the Random Primer Labeling Kit (TaKaRa, Dalian, China). Total RNAs were extracted with an RNA extraction kit (Invitrogen, USA) from vegetative mycelia. The crude RNA was pre-treated with DNase I (TaKaRa) and was then reverse transcribed with a PrimeScript RT-PCR Kit (TaKaRa). RT-PCR was performed to evaluate splicing efficiency of selected intron with a pair of primers crossing it. All PCR primers (Additional file 1: Table S4) were synthesized by Sangon (Shanghai, China).

Bioinformatic analysis

MoGrp1 sequences were downloaded from the Magnaporthe oryzae genome database at NCBI. The related homology sequences from different organisms were obtained from GenBank using the BLAST algorithm. Protein domain predictions were made using the Pfam database (http://pfam.xfam.org/). Protein alignments were assembled using MAFFT (Katoh et al. 2002) and visualized using CLC Sequence viewer (Knudsen and Chalkley 2011) and BoxShade (V3.21, Hoffman, Bioinformatics Group). Phylogenetic analysis of Grp1 proteins was conducted using the distance analysis algorithm of MEGA6 (http://www.megasoftware.net/) with the Dayhoff model, and the number of bootstrap replications was set to 1000.

Targeted deletion of MoGRP1

To construct the MoGRP1 gene replacement vector pKO-MoGRP1, we designed the primer pairs koF1/koR1 and koF2/koR2 amplifying ~ 1.5 kb upstream and ~ 1.5 kb downstream fragments from P131 genomic DNA, respectively, followed by BamHI/PstI and ClaI/XhoI enzymatic digestions, and inserted into vector pKOV21 containing hygromycin resistance gene as described in Additional file 2: Figure S1. The vector pKO-MoGRP1 was transformed into protoplasts of strain P131 to generate null mutants as previously described (Kong et al. 2012). Transformants were selected via hygromycin resistance and then screened using the primer pairs CHECK-UP/HPT-UP and CHECK-DOWN/HPT-DOWN. The resulting transformants were confirmed by Southern blot assay. Fungal genomic DNA isolation and Southern blot assay were performed as described, in which the genomic DNA was digested by XhoI and probed by the upstream fragment (Li et al. 2014).

Subcellular location, gene complementation, and domain deletion assay

For complementation and subcellular location assay, the MoGRP1 fragment amplified with the primer pair MoGRP1-F/MoGRP1-G-R was cloned into pRGTN harboring a RP27 promoter and a C-terminal fused GFP by EcoRI and SpeI. For co-immunoprecipitation and RNA-binding assays, the MoGRP1 fragment amplified with the primer pair MoGRP-F/MoGRP-R was cloned into pRFTN harboring a RP27 promoter and an N-terminal 3×Flag-tag sequence by EcoRI and SpeI. To dissect functions of different domains of MoGrp1, we amplified the MoGRP1 fragments with the primer pairs, MoGRP1-F/G181-R, MoGRP1-F/G190-R, MoGRP1-F/G264-R, N-F/MoGRP1-G-R, NR-F/MoGRP1-G-R, and N-F/G190-R, and then inserted these fragments into pRGTN by EcoRI and SpeI. For RNP-2 deletion (RNP-2-F/R) and 181–190 aa deletion (190-F/181-R), the vector was constructed by reverse PCR from pRGTN-MoGRP1 and the resulting product was digested with DpnI and self-linked. The RNP-2 deletion vector was also constructed from pRFTN-MoGRP1. The AGG point mutation vector was constructed by Tsingke company (Beijing, China). These vectors were reintroduced into the MoGRP1 deletion mutant. All transformants were first screened by neomycin resistance, and then the 3 × Flag-tag transformants were confirmed by western blot assay. The GFP transformants were first stained by DAPI and then observed with a Nikon Fluorescence microscopy Ni900 (Japan) (Odenbach et al. 2007).

Appressorium formation and plant infection assay

Appressorium formation on an artificial cover glass slide hydrophobic surface was assayed using conidia harvested with 2 mL sterilized distilled water from 7-day-old OTA cultures, and appressorium formation rate was assessed at 24 hpi as described (Yang et al. 2012). Infection assays were performed with 2 μL of 1 × 105 conidia/mL in 0.025% Tween-20 on barley and rice leaves or 2 mm2 mycelial blocks on rice leaves. The invasive hyphal growth was examined at 24, 36, and 48 hpi (Chen et al. 2014). A concentration of 2 × 104 conidia/mL in a 0.025% Tween-20 solution was applied for spraying onto seedlings of 4-week-old susceptible rice cultivar ‘LTH’ and 8-day-old barley cultivar ‘E9’. The infected plants were incubated in a moist chamber and maintained as previously described (Peng et al. 1988). Lesion formation was examined at 5–7 days post inoculation (dpi), and the mean number of disease lesions formed on 5 cm long tip leaf was determined as described (Peng et al. 1988).

Affinity protein purification and MS analysis

Strain expressing the 3 × Flag-MoGrp1 fusion was used for expression and protein purification. M. oryzae mycelia grown 7 days on OTA plates were washed out and grown in 200 mL liquid CM in a shaker at 25 °C at 160 rpm for 48 h. Total proteins were extracted from 1.0–1.5 g of the mycelia. The mycelia were collected by filtering through a layer of filter paper, washed with sterile water and ground in liquid nitrogen. Then, total proteins were extracted with 6 mL of extraction buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100) and 20 μL/mL Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Sigma, USA). After centrifugation for 30 min at 4 °C at 12,000 rpm, the supernatant was used for purification. Supernatant (5 mL) was incubated with 200 μL of Anti-FLAG M2 magnetic beads (Sigma, USA) for 2 h, and washed with TBS (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4; 150 mM NaCl) three times. The bound proteins were then eluted using TBS with 200 μL of FLAG peptide (300 ng/mL, Sigma, USA) and incubated for 1 h. The eluted protein was detected by anti-Flag antibody (Li et al. 2011), and was used for MS analysis and RNA/DNA binding assay. MS analysis was performed as described (Han and Li 2016). The eluant was analyzed by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) after digestion with trypsin (Li et al. 2017). The MS data results were used to search against NCBI nr M. oryzae protein database to identify MoGrp1-interacting proteins as described (Li et al. 2017).

RNA and DNA binding assays

RNA and DNA binding assays were performed using the μMACS Streptavidin Kit (Miltenyi Biotec, UK) as described (Franceschetti et al. 2011). The binding reaction contained 0.3 μg protein, 0.2 nM biotinylated poly(A)30 or poly(U)30 RNA homopolymers (Sangon, China), and binding buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 0.01% NP-40, 2 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT). 100 μL of MACS streptavidin magnetic beads was added into the mixture and incubated at 4 °C for 1 h. The proteins were then eluted from beads using 50 μL binding buffer with 1% SDS. The elution was loaded onto 12% SDS-PAGE and was detected by western blot with an anti-Flag antibody (1:5000; Abmart, China).

Co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) assay

The MoGar1-GFP fusion vector pRGTN-MoGAR1 was constructed by amplifying the MoGAR1 fragment with the primer pair MoGAR1-F/MoGAR1-R and co-transformed with pRFTN-MoGRP1 into the wild-type strain P131. Transformants CoFG1 expressing the MoGar1-GFP and 3 × Flag-MoGrp1 constructs were first screened by PCR and then confirmed by western blot with an anti-GFP antibody and an anti-Flag antibody, respectively. The coimmunoprecipitation assay was performed using Anti-FLAG M2 Magnetic beads (Sigma, USA) as previously described (Qi et al. 2012). Proteins eluted from anti-FLAG M2 magnetic beads were detected with an anti-GFP antibody and an anti-Flag antibody. The coimmunoprecipitation assay between MoGrp1 and MoRse1 was performed in the same way to obtain transformants CoFG9 expressing the MoRse1-GFP and 3 × Flag-MoGrp1 constructs. CoFG1 and CoFG9 total proteins were used as positive controls. The transformants expressing MoGar1-GFP or MoRse1-GFP alone were used as negative controls.

Yeast two-hybrid assay

To generate Gal4-BD fusion proteins, MoGrp1 cDNA was cloned into pGBKT7 vectors using NdeI/BamHI. Fusion proteins containing Gal4-AD were obtained by cloning the different cDNAs into the pGADT7 vector using NdeI/BamHI. Both plasmids containing target proteins fused to AD and BD were co-transformed into Saccharomyces cerevisiae Y2HGold strain by using the MATCHMAKER GAL4 Two-Hybrid System 3 (Clontech, USA). The Trp+Leu+ transformants were collected and further confirmed by plating onto SD/−Trp/−Leu/-His medium and assayed by X-α-gal staining for LacZ activity (Li et al. 2017). Yeast strains harboring the pGBKT7–53/pGADT7-T or pGBKT7-Lam/pGADT7-T pairs were used as the positive or the negative control, respectively.

Abbreviations

- A. thaliana :

-

Arabidopsis thaliana

- aa:

-

Amino acid

- C. elegans :

-

Caenorhabditis elegans

- CFW:

-

Calcofluor White

- CM:

-

Complete medium

- CR:

-

Congo Red

- D. discoideum :

-

Dictyostelium discoideum

- D. melanogaster :

-

Drosophila melanogaster

- D. rerio :

-

Danio rerio

- DAPI:

-

4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride

- F. oxysporum :

-

Fusarium oxysporum

- G. max :

-

Glycine max

- GRP:

-

Glycine-rich RNA-binding proteins

- H. sapiens :

-

Homo sapiens

- Hyg :

-

Hygromycin resistance gene

- M. musculus :

-

Mus musculus

- M. oryzae :

-

Magnaporthe oryzae

- MM:

-

Minimal medium

- MM-C:

-

Carbon-free minimal medium

- MM-N:

-

Nitrogen-free minimal medium

- N. crassa :

-

Neurospora crassa

- OTA:

-

Oatmeal tomato agar

- P. falciparum :

-

Plasmodium falciparum

- qRT-PCR:

-

Quantitative real time polymerase chain reaction

- RGG:

-

Arg-Gly-Gly tri-peptide

- RRM:

-

RNA recognition motif

- S. cerevisiae :

-

Saccharomyces cerevisiae

- S. pombe :

-

Schizosaccharomyces pombe

- SDS:

-

Sodium dodecyl sulfate

- TF:

-

Transcription factor

- U. maydis :

-

Ustilago maydis

References

Al-Astal HI, Massad M, AlMatar M, Ekal H. Cellular functions of RNA-binding motif protein 3 (RBM3): clues in hypothermia, cancer biology and apoptosis. Protein Pept Lett. 2016;23:828–35.

Ariyachet C, Beißel C, Li X, Lorrey S, Mackenzie O, Martin PM, et al. Post-translational modification directs nuclear and hyphal tip localization of C. albicans mRNA-binding protein Slr1. Mol Microbiol. 2017;104:499–519.

Aznarez I, Barash Y, Shai O, He D, Zielenski J, Tsui LC, et al. A systematic analysis of intronic sequences downstream of 5′ splice sites reveals a widespread role for U-rich motifs and TIA1/TIAL1 proteins in alternative splicing regulation. Genome Res. 2008;18:1247–58.

Becht P, Vollmeister E, Feldbrügge M. Role for RNA-binding proteins implicated in pathogenic development of Ustilago maydis. Eukaryot Cell. 2005;4:121–33.

Bousquet-Antonelli C, Henry Y, G’elugne JP, Caizergues-Ferrer M, Kiss T. A small nucleolar RNP protein is required for pseudouridylation of eukaryotic ribosomal RNAs. EMBO J. 1997;16:4770–6.

Brahms H, Meheus L, De Brabandere V, Fischer U, Lührmann R. Symmetrical dimethylation of arginine residues in spliceosomal Sm protein B/B’ and the Sm-like protein LSm4, and their interaction with the SMN protein. RNA. 2001;7:1531–42.

Breth B, Odenbach D, Yemelin A, et al. The role of the Tra1p transcription factor of Magnaporthe oryzae in spore adhesion and pathogenic development. Fungal Genet Biol. 2013;57:11–22.

Cao H, Huang P, Zhang L, et al. Characterization of 47 Cys2-His2 zinc finger proteins required for the development and pathogenicity of the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae. New Phytol. 2016;211:1035–51.

Cartegni L, Chew SL, Krainer AR. Listening to silence and understanding nonsense: exonic mutations that affect splicing. Nat Rev Genet. 2002;3:285–98.

Caspary F, Shevchenko A, Wilm M, Séraphin B. Partial purification of the yeast U2 snRNP reveals a novel yeast pre-mRNA splicing factor required for pre-spliceosome assembly. EMBO J. 1999;18:3463–74.

Chen EJ, Frand AR, Chitouras E, Kaiser CA. A link between secretion and pre-mRNA processing defects in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and the identification of a novel splicing gene, RSE1. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:7139–46.

Chen XL, Shen M, Yang J, Xing YF, Chen D, Li ZG, et al. Peroxisomal fission is induced during appressorium formation and is required for full virulence of the rice blast fungus. Mol Plant Pathol. 2017;18:222–37.

Chen XL, Shi T, Yang J, Shi W, Gao XS, Chen D, et al. N-glycosylation of effector proteins by an α-1,3-mannosyltransferase is required for the rice blast fungus to evade host innate immunity. Plant Cell. 2014;26:1360–76.

Ciuzan O, Hancock J, Pamfil D, Wilson I, Ladomery M. The evolutionarily conserved multifunctional glycine-rich RNA-binding proteins play key roles in development and stress adaptation. Physiol Plant. 2015;153:1–11.

Condit CM, McLean BG, Meagher RB. Characterization of the expression of the petunia glycine-rich protein-1 gene product. Plant Physiol. 1990;93:596–602.

Condit CM, Meagher RB. A gene encoding a novel glycine-rich structural protein of petunia. Nature. 1986;323:178–81.

Dean R, Van Kan JA, Pretorius ZA, Hammond-Kosack KE, Di Pietro A, Spanu PD, et al. The top 10 fungal pathogens in molecular plant pathology. Mol Plant Pathol. 2012;13:414–30.

Deka P, Bucheli ME, Moore C, Buratowski S, Varani G. Structure of the yeast SR protein Npl3 and interaction with mRNA 3′-end processing signals. J Mol Bio. 2008;375:136–50.

Del Gatto-Konczak F, Bourgeois CF, Le Guiner C, Kister L, Gesnel MC, Stévenin J, et al. The RNA-binding protein TIA-1 is a novel mammalian splicing regulator acting through intron sequences adjacent to a 5′ splice site. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:6287–99.

Franceschetti M, Bueno E, Wilson RA, Tucker SL, Gómez-Mena C, Calder G, et al. Fungal virulence and development is regulated by alternative pre-mRNA 3′-end processing in Magnaporthe oryzae. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002441.

Gao XL, Jin QJ, Jiang C, Li Y, Li CH, Liu HQ, et al. FgPrp4 kinase is important for spliceosome B-complex activation and splicing efficiency in Fusarium graminearum. PLoS Genet. 2016;12:e1005973.

Gendra E, Moreno A, Alba MM, Pages M. Interaction of the plant glycine-rich RNA-binding protein MA16 with a novel nucleolar DEAD box RNA helicase protein from Zea mays. Plant J. 2004;38:875–86.

Hamer JE, Talbot NJ. Infection-related development in the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe grisea. Curr Opin Microbiol. 1998;1:693–7.

Han M, Li Z. Mesoporous metal oxide nanoparticles for selective enrichment of phosphopeptides from complex sample matrices. Anal Methods. 2016;8:7747–54.

Hegele A, Kamburov A, Grossmann A, Sourlis C, Wowro S, Weimann M, et al. Dynamic protein-protein interaction wiring of the human spliceosome. Mol Cell. 2012;45:567–80.

Katoh K, Misawa K, Kuma K, Miyata T. MAFFT: A novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast Fourier transform. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:3059–66.

Kim JS, Jung HJ, Lee HJ, Kim KA, Goh CH, Woo Y, et al. Glycine-rich RNA-binding protein 7 affects abiotic stress responses by regulating stomata opening and closing in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2008;55:455–66.

Knudsen GM, Chalkley RJ. The effect of using an inappropriate protein database for proteomic data analysis. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20873.

Kong LA, Yang J, Li GT, Qi LL, Zhang YJ, Wang CF, et al. Different chitin synthase genes are required for various developmental and plant infection processes in the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002526.

Kong S, Park SY, Lee YH. Systematic characterization of the bZIP transcription factor gene family in the rice blast fungus, Magnaporthe oryzae. Environ Microbiol. 2015;17:1425–43.

Kupsch C, Ruwe H, Gusewski S, Tillich M, Small I, Schmitz-Linneweber C. Arabidopsis chloroplast RNA binding proteins CP31A and CP29A associate with large transcript pools and confer cold stress tolerance by influencing multiple chloroplast RNA processing steps. Plant Cell. 2012;24:4266–80.

Li C, Yang J, Zhou W, Chen XL, Huang JG, Cheng ZH, et al. A spindle pole antigen gene MoSPA2 is important for polar cell growth of vegetative hyphae and conidia, but is dispensable for pathogenicity in Magnaporthe oryzae. Curr Genet. 2014;60:255–63.

Li GT, Zhang X, Tian H, Choi YE, Tao WA, Xu JR. MST50 is involved in multiple MAP kinase signaling pathways in Magnaporthe oryzae. Environ Microbiol. 2017;19:1959–74.

Li GT, Zhou XY, Kong LA, Wang YL, Zhang HF, Zhu H, et al. MoSfl1 is important for virulence and heat tolerance in Magnaporthe oryzae. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19951.

Li L, Ye K. Crystal structure of an H/ACA box ribonucleoprotein particle. Nature. 2006;443:302–7.

Liu HQ, Li Y, Chen DP, Qi ZM, Wang QH, Wang JH, et al. A-to-I RNA editing is developmentally regulated and generally adaptive for sexual reproduction in Neurospora crassa. Proc Nati Acad Sci USA. 2017;114:E7756–65.

Liu HQ, Wang QH, He Y, Chen LF, Hao CF, Jiang C, et al. Genome-wide A-to-I RNA editing in fungi independent of ADAR enzymes. Genome Res. 2016;26:499–509.

Lu JP, Cao HJ, Zhang LL, Huang PY, Lin FC. Systematic analysis of Zn2Cys6 transcription factors required for development and pathogenicity by high-throughput gene knockout in the rice blast fungus. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1004432.

Mangeon A, Junqueira RM, Sachetto-Martins G. Functional diversity of the plant glycine-rich proteins superfamily. Plant Signal Behav. 2010;5:99–104.

McBride AE, Cook JT, Stemmler EA, Rutledge KL, McGrath KA, Rubens JA. Arginine methylation of yeast mRNA-binding protein Npl3 directly affects its function, nuclear export, and intranuclear protein interactions. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:30888–98.

Mears WE, Rice SA. The RGG box motif of the herpes simplex virus ICP27 protein mediates an RNA-binding activity and determines in vivo methylation. J Virol. 1996;70:7445–53.

Miller MM, Read LK. Trypanosoma brucei: functions of RBP16 cold shock and RGG domains in macromolecular interactions. Exp Parasitol. 2003;105:140–8.

Moehle EA, Ryan CJ, Krogan NJ, Kress TL, Guthrie C. The yeast SR-like protein npl3 links chromatin modification to mRNA processing. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1003101.

Nichols RC, Wang XW, Tang J, Hamilton BJ, High FA, Herschman HR, et al. The RGG domain in hnRNP A2 affects subcellular localization. Exp Cell Res. 2000;256:522–32.

Odenbach D, Breth B, Thines E, Weber RW, Anke H, Foster AJ, et al. The transcription factor Con7p is a central regulator of infection-related morphogenesis in the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe grisea. Mol Microbiol. 2007;64:293–307.

Peng Y, Yang PH, Tanner JA, Huang JD, Li M, Lee HF, et al. Cold-inducible RNA binding protein is required for the expression of adhesion molecules and embryonic cell movement in Xenopus laevis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;344:416–24.

Peng YL, Shishiyama J. Temporal sequence of cytological events in rice leaves infected with Pyricularia oryzae. Can J Bot. 1988;66:730–5.

Qi ZQ, Wang Q, Dou XY, Wang W, Zhao Q, Lv RL, et al. MoSwi6, an APSES family transcription factor, interacts with MoMps1 and is required for hyphal and conidial morphogenesis, appressorial function and pathogenicity of Magnaporthe oryzae. Mol Plant Pathol. 2012;13:677–89.

Rajyaguru P, Parker R. RGG motif proteins modulators of mRNA functional states. Cell Cycle. 2012;11:2594–9.

Rodríguez-Romero J, Franceschetti M, Bueno E, Sesma A. Multilayer regulatory mechanisms control cleavage factor I proteins in filamentous fungi. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:179–95.

Sambrook J, Russell D. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 3rd ed. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2001.

Schmidt F, Marnef A, Cheung M-K, Wilson I, Hancock J, Staiger D, et al. A proteomic analysis of oligo(dT)-bound mRNP containing oxidative stress-induced Arabidopsis thaliana RNA-binding proteins ATGRP7 and ATGRP8. Mol Biol Rep. 2010;37:839–45.

Shi HB, Chen GQ, Chen YP, Dong B, Lu JP, Liu HX, et al. MoRad6-mediated ubiquitination pathways are essential for development and pathogenicity in Magnaporthe oryzae. Environ Microbiol. 2016a;18:4170–87.

Shi X, Germain A, Hanson MR, Bentolila S. RNA recognition motif-containing protein ORRM4 broadly affects mitochondrial RNA editing and impacts plant development and flowering. Plant Physiol. 2016b;170:294–309.

Singh R, Valcárcel J. Building specificity with nonspecific RNA-binding proteins. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2005;12:645–53.

Talbot NJ. On the trail of a cereal killer: exploring the biology of Magnaporthe grisea. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2003;57:177–202.

Talbot NJ, Foster AJ. Genetics and genomics of the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe grisea: developing an experimental model for understanding fungal diseases of cereals. Adv Bot Res. 2001;34:263–87.

Tanaka K, Watakabe A, Shimura Y. Polypurine sequences within a downstream exon function as a splicing enhancer. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:1347–54.

Tang S, Patel A, Krause PR. Herpes simplex virus ICP27 regulates alternative pre-mRNA polyadenylation and splicing in a sequence-dependent manner. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:12256–61.

Tremblay A, Lamontagne B, Catala M, Yam Y, Larose S, Good L, et al. A physical interaction between Gar1p and Rnt1pi is required for the nuclear import of H/ACA small nucleolar RNA-associated proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:4792–802.

Vollmeister E, Haag C, Zarnack K, Baumann S, König J, Mannhaupt G, et al. Tandem KH domains of Khd4 recognize AUACCC and are essential for regulation of morphology as well as pathogenicity in Ustilago maydis. RNA. 2009;15:2206–18.

Wahl MC, Will CL, Lührmann R. The spliceosome: design principles of a dynamic RNP machine. Cell. 2009;136:701–18.

Wang JY, Zhang Z, Wang YL, Li L, Chai RY, Mao XQ, et al. PTS1 peroxisomal import pathway plays shared and distinct roles to PTS2 pathway in development and pathogenicity of Magnaporthe oryzae. PLoS One. 2013;8:e55554.

Wang Y, He D, Chu Y, Zuo YS, Xu XW, Chen XL, et al. MoCps1 is important for conidiation, conidial morphology and virulence in Magnaporthe oryzae. Curr Genet. 2016;62:861–71.

Wong CM, Tang HM, Kong KY, Wong GW, Qiu HF, Jin DY, et al. Yeast arginine methyltransferase Hmt1p regulates transcription elongation and termination by methylating Npl3p. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:2217–28.

Wongpalee SP, Vashisht A, Sharma S, Chui D, Wohlschlegel JA, Black DL. Large-scale remodeling of a repressed exon ribonucleoprotein to an exon definition complex active for splicing. elife. 2016;5:e19743.

Xu JR, Hamer JE. MAP kinase and cAMP signaling regulate infection structure formation and pathogenic growth in the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2696–706.

Yang J, Kong LG, Chen XL, Wang DW, Qi LL, Zhao WS, et al. A carnitine-acylcarnitine carrier protein, MoCrc1, is essential for pathogenicity in Magnaporthe oryzae. Curr Genet. 2012;58:139–48.

Zhang Y, Gao X, Sun M, Liu H, Xu JR. The FgSRP1 SR-protein gene is important for plant infection and pre-mRNA processing in Fusarium graminearum. Environ Microbiol. 2017;19:4065–79.

Zhao X, Kim Y, Park G, Xu JR. A mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade regulating infection-related morphogenesis in Magnaporthe grisea. Plant Cell. 2005;17:1317–29.

Acknowledgements

We thank Professor Jun Fan from China Agricultural University and Professor Tom Hsiang from University of Guelph for editorial assistance.

Funding

This study was funded by Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 31872916), Beijing Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. 6172020), National Key Research and Development Plan (Grant No. 2016YFD0300703), and PCSIRT (Grant No. IRT1042). The funders had no roles in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

XG, CY, XL, JP, DC, DH, and WS performed the experiments. All authors analyzed the data. JY and Y-LP designed the study. JY and XG wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Table S1. Annotation of RRM-containing proteins in Magnaporthe oryzae. Table S2. Inhibition ratio of vegetative hyphal growth of the strains under different stress conditions (%). Table S3. Fungal strains used in this study. Table S4. PCR primers used in this study. (DOCX 32 kb)

Additional file 2:

Figure S1. Sequence alignment of MoGrp1 and its orthologous proteins from the following 15 species. M. oryzae (XP_003711424.1), Fusarium oxysporum (XP_018238834.1), Neurospora crassa (CAC28728.2), Saccharomyces cerevisiae (NP_014382.1), Schizosaccharomyces pombe (XP_001713104.1), Glycine max (XP_003530834.1), Arabidopsis thaliana (NP_563787.2), Ustilago maydis (XP_011388843.1), Caenorhabditis elegans (NP_001255142.1), Mus musculus (NP_932770.2), Homo sapiens (NP_001269688.1), Danio rerio (NP_955945.2), Drosophila melanogaster (NP_652612.1), Dictyostelium discoideum (XP_629578.1) and Plasmodium falciparum (XP_001347313.1). Identical residues among these sequences are marked with a black and gray shadow. (TIF 2342 kb)

Additional file 3:

Figure S2. Targeted deletion of MoGRP1. (A) Schematic diagram showing the strategy of MoGRP1 replacement by the hygromycin resistance gene hyg. The gene knock-out vector of MoGRP1 was constructed by amplifying the flanking sequences with primer pairs koF1/koR1 and koF2/koR2 and were ligated with the hph cassette. (B) DNA gel blot analysis of the wild-type strain P131 and one ΔMogrp1 deletion mutant kg1. The genomic DNAs were digested by XhoI, hybridized with the probe, and amplified with the primer pair koF1/koR1. The estimated size of each band is labeled on the left. (TIF 402 kb)

Additional file 4:

Figure S3. The ΔMogrp1 mutant has a partial loss of hydrophobicity. A drop of 10 μL ddH2O or 0.2% SDS solution was placed on 10-day-old colony of the wild-type P131 and ΔMogrp1 deletion mutant kg1 on OTA plate. Bar, 5 mm. (TIF 703 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Gao, X., Yin, C., Liu, X. et al. A glycine-rich protein MoGrp1 functions as a novel splicing factor to regulate fungal virulence and growth in Magnaporthe oryzae. Phytopathol Res 1, 2 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42483-018-0007-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s42483-018-0007-1