Abstract

Background

Information about contemporary fire regimes across the Sky Island mountain ranges of the Madrean Archipelago Ecoregion in the southwestern United States and northern Mexico can provide insight into how historical fire management and land use have influenced fire regimes, and can be used to guide fuels management, ecological restoration, and habitat conservation. To contribute to a better understanding of spatial and temporal patterns of fires in the region relative to environmental and anthropogenic influences, we augmented existing fire perimeter data for the US by mapping wildfires that occurred in the Mexican Sky Islands from 1985 to 2011.

Results

A total of 254 fires were identified across the region: 99 fires in Mexico (μ = 3901 ha, σ = 5066 ha) and 155 in the US (μ = 3808 ha, σ = 8368 ha). The Animas, Chiricahua, Huachuca-Patagonia, and Santa Catalina mountains in the US, and El Pinito in Mexico had the highest proportion of total area burned (>50%) relative to Sky Island size. Sky Islands adjacent to the border had the greatest number of fires, and many of these fires were large with complex shapes. Wildfire occurred more often in remote biomes, characterized by evergreen woodlands and conifer forests with cooler, wetter conditions. The five largest fires (>25 000 ha) all occurred during twenty-first century droughts (2002 to 2003 and 2011); four of these were in the US and one in Mexico. Overall, high variation in fire shape and size were observed in both wetter and drier years, contributing to landscape heterogeneity across the region.

Conclusions

Future research on regional fire patterns, including fire severity, will enhance opportunities for collaborative efforts between countries, improve knowledge about ecological patterns and processes in the borderlands, and support long-term planning and restoration efforts.

Resumen

Antecedentes

Información sobre los regímenes de fuegos contemporáneos que ocurren a través de las cadenas montañosas de Sky Island en la eco-región del archipiélago Madrean en el sudoeste de los EEUU y el norte de México pueden brindar una visión sobre como el manejo histórico del fuego ha influenciado los regímenes de fuego, y puede ser usado como guía para el manejo de combustibles, la restauración ecológica y la conservación del hábitats. Para contribuir a una mejor comprensión de los patrones espaciales y temporales de fuegos en la región relacionados con influencias ambientales y antrópicas, aumentamos el perímetro de datos existente para los EEUU mediante el mapeo de incendios que ocurrieron en las cadenas montañosas de Sky Islands en México desde 1985 hasta 2011.

Resultados

Un total de 254 incendios fueron identificados a través de toda la región: 99 incendios en México (μ = 3901 ha, σ = 5066 ha) y 155 en los EEUU (μ = 3808 ha, σ = 8368 ha). Los sitios denominados las Animas, Chiricahua, Huachuca-Patagonia, y las montañas de Santa Catalina en los EEUU, y El Pinito en México concentraron la mayor proporción del área quemada (>50%) en relación al tamaño de la región Sky Island. Las Sky Islands adyacentes al límite entre los dos países tuvieron el mayor número de incendios, y muchos de ellos fueron grandes y con formas complejas. Los incendios ocurrieron más frecuentemente en biomas remotos, caracterizados por bosques siempreverdes y bosques de coníferas con condiciones frías y húmedas. Los incendios más grandes (>25 000 ha) ocurrieron durante las primeras sequías del siglo XXI (2002 a 2003, y 2011); cuatro de ellos fueron en los EEUU y uno en México. En general, una gran variación en forma y tamaño de incendios fue observado entre años húmedos y secos, contribuyendo a la heterogeneidad del paisaje a través de la región.

Conclusiones

Investigaciones futuras en el patrón regional del fuego, incluyendo la severidad, va a mejorar las oportunidades para los esfuerzos colaborativos entre ambos países, mejorar el conocimiento sobre los patrones y procesos ecológicos en áreas fronterizas, y apoyar planificaciones a largo plazo y esfuerzos en la restauración.

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

ATCOR: ATmospheric CORrection

dNBR: differenced Normalized Burn Ratio

FIRMS: Fire Information for Resource Management System

GLOVIS: GLObal VISualization Viewer

MODIS: MODerate resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer

MTBS: Monitoring Trends in Burn Severity

NBR: Normalized Burn Ratio

NIR: Near InfraRed

PSDI: Palmer Drought Severity Index

scPDSI: self-calibrating Palmer Drought Severity Index

SEDAC: SocioEconomic Data and Applications Center

SRTM: Shuttle Radar Topography Mission

SWIR: ShortWave InfraRed

USAID: US Agency for International Development

USGS: United States Geological Survey

Background

In today’s world, understanding between neighboring countries is more vital than ever (Riding 1989). Although the importance of history, culture, and socioeconomic conditions is often emphasized, ecological processes that shape the distribution of species and communities, and thus support resources essential to human livelihoods, are equally critical components of integrated systems that transcend political borders (Liu et al. 2007). Wildland fire is an important ecological process that shapes the distribution of species and communities and associated ecosystem services. Wildfire can enhance or reduce species habitat and connectivity, alter water cycle processes and induce erosion, and influence forest carbon budgets (Cannon et al. 2010, Hurteau and Brooks 2011, Williams et al. 2014, Hutto et al. 2016). Information on the timing, location, and patterns of fires is key to understanding the physical, biological, and ecological processes that generate those patterns, including evolutionary processes that drive biological and ecological diversity upon which people depend (Bond and Keeley 2005, Burton et al. 2009, Whitman et al. 2015).

Maps of fire occurrence are a key resource in management and ecological restoration efforts, and can provide insight into the effects of land use, climate, and topography on contemporary fire regimes (Morgan et al. 2001; Stephens and Fulé 2005; Miller et al. 2012a, b). Where available, consistent and accurate data on fire regimes, including frequency, severity, and spatial pattern, facilitate important decisions regarding sustainable forest management and reduction of fuels to control fire risk (Bergeron et al. 2004, Petrakis et al. 2018). Furthermore, fires increase the spatial heterogeneity of vegetation at multiple scales; knowledge of fire regime attributes can be used to understand how fires create, maintain, or otherwise alter wildlife and plant habitats, as well as how fires support or disrupt the connectivity of those habitats (Zozaya et al. 2011). Importantly, fire regimes are expected to change with climate; alterations have already been observed at local to global scales (Hurteau et al. 2014). In places where resources necessary to develop and support fire mapping programs are limited, it is impossible to address these priority issues in a way that is comparable with adjoining countries in which mapping programs are well established.

In the US, federal agencies developed the Monitoring Trends in Burn Severity (MTBS) program to provide a comprehensive, national database of wildfire information about “large” fires (>404 ha in the West and >202 ha in the East) from 1984 to the present (Eidenshink et al. 2007). MTBS data have been used to examine regional and national wildfire trends related to vegetation type, topography, forest management, and climate, providing information to guide policy and management decisions (Wimberly et al. 2009, Dillon et al. 2011, Miller et al. 2012a, Baker 2013). Prior to our efforts, a fire database for northern Mexico that is comparable to MTBS did not exist, and institutional information on wildfires that burned in remote areas was lacking due primarily to complex land ownership (i.e., more communal and private land in forests of Mexico compared to lands administered by federal agencies in the US) and limited forestry and firefighting budgets (Rodríguez-Trejo 2008, Villarreal and Yool 2008). Our work is an important first step in characterizing contemporary fire regimes in a cross-border region with outstanding biodiversity (Whittaker and Nearing 1965, Coblentz and Riiters 2004) that is expected to experience the ecological impacts of climate change sooner than other areas of western North America (Notaro et al. 2012).

The objectives of this research were to quantify the spatial and temporal patterns of recent (1985 to 2011) fire occurrence across the Madrean Archipelago Ecoregion of North America, and to analyze these patterns relative to significant climate, topography, ignition sources, and land cover variables. The Madrean Ecoregion provides a unique setting to study spatial patterns of wildfire: mountains in the ecoregion are biogeographically similar, but the region is divided in half by the United States−Mexico international border, where contrasting land uses and forest management approaches often occur. We posed the following questions:

-

1)

What are the basic characteristics of contemporary fire regimes across the study region?

-

2)

How do spatial patterns of fires vary regionally, and within each Sky Island mountain range?

-

3)

How does inter-annual climate variability influence fire patterns?

-

4)

How does underlying spatial heterogeneity in climate, topography, ignition sources, and land cover define burned and unburned environments?

Methods

Study area

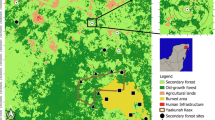

Covering a geographic area of approximately 74 788 km2, the Madrean Archipelago Ecoregion (Omernik 1987) encompasses portions of northern Sonora and Chihuahua in Mexico, and southeastern Arizona and southwestern New Mexico in the US (Fig. 1). Characterized by a basin and range topography with elevations ranging from 600 m in the valley floors (Tepache, Sonora) to 3267 m (Mount Graham, Arizona), the Madrean Archipelago consists of isolated forested mountains (referred to as Sky Islands) surrounded by desert lowlands, semi-arid grasslands, and shrub steppe vegetation (Warshall 1995). The ecoregion contains 39 Sky Island mountain complexes that make up more than half of the total land area (42 729 km2; Fig. 1; Warshall 1995). The international border, established after the Gadsden Purchase in 1853, cuts through the center of the ecoregion at 31°33' N (Fig. 1). Twenty-two of the Sky Islands fall primarily within the US and 17 in Mexico. Three ranges—the Atascosa-Cibuta, Huachuca-Patagonia, and Peloncillo-Pan Duro—cross the international border. Characteristics of the 30 Sky Islands that had fires during the study period are presented in Table 1.

Climate of the Madrean Archipelago is characterized by a bimodal precipitation pattern. Winter (November to March) frontal storms bring snow to higher elevations and rain to the lower elevations. In mid to late summer (July to August), moisture from the south creates a monsoonal weather pattern with thunderstorms. The arid foresummer period (April to June) preceding the monsoonal moisture is typically hot and dry and generally corresponds to the fire season. Annual precipitation varies greatly by elevation, with orographic uplift contributing to increased precipitation at upper elevations. The average annual precipitation ranges from about 232 mm at 820 m above sea level to 1035 mm at 3267 m (Fort Thomas, Arizona, and Mount Graham, Pinaleño Mountains, respectively; Hamann et al. 2013).

Sky Island Vegetation

Upland vegetation of the ecoregion generally consists of Sonoran Desertscrub, Chihuahuan Desertscrub, and Sinaloan Desertscrub, and Semidesert Grasslands in the low-elevation valleys and flats, and Madrean Evergreen Woodlands, Montane Conifer Forests, and Subalpine Conifer Forests at the upper elevations (Brown et al. 1979). The sharp vertical relief and unique geographic position of the Sky Islands combine to create a diverse mosaic of vegetation assemblages stratified along elevation and moisture gradients (Niering and Lowe 1984). The Rocky Mountain Cordillera vegetation influence from the north is more prevalent at higher elevations (above 2000 m) while the Madrean vegetation influence from the south dominates lower elevations (below 2000 m) (McLaughlin 1994). Coniferous vegetation within the Sky Islands is generally divided into five types: pinyon−juniper woodlands, Madrean evergreen woodlands, pine−oak forests, pure pine forests, and mixed-conifer forests (Iniguez et al. 2005).

Pinyon−juniper woodlands typically occur in areas below 1800 m elevation, although they can also be found at higher elevations on drier south-facing aspects. The dominant tree species within the pinyon−juniper plant community include alligator juniper (Juniperus deppeana Steud.), Rocky Mountain juniper (J. scopulorum Sarg.), one-seed juniper (J. monosperma [Engelm.] Sarg.), pinyon pine (Pinus edulis Engelm.), and border pinyon (P. discolor D.K. Bailey and Hawksw). Madrean oak woodlands generally occur at low to mid elevation and are dominated by evergreen oak including silverleaf oak (Quercus hypoleucoides A. Camus), Arizona white oak (Q. arizonica Sarg.), Emory oak (Q. emoryi Torr.), and Mexican blue oak (Q. oblongifolia). Mid-elevation pine forests are dominated by ponderosa pine (P. ponderosa C. Lawson) and Gambel oak (Q. gambelii Nutt.). Higher elevation forests are dominated by Apache pine (P. engelmanii Carr.), Chihuahua pine (P. leiophylla Schiede & Deppe), and Arizona pine (P. arizonica Engelm.). Mixed-conifer forests are generally found between 2500 and 3000 m and typically include Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii [Mirb.] Fanco), white fir (Abies concolor [Gord. & Glend.] Hildebr.), southwestern white pine (P. strobiformis Engelm.), quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides Michx.), and ponderosa pine.

Cultural history

The oldest known inhabitants of the general area were the Hohokam, who, as farmers, mainly occupied the desert valley bottoms near reliable water sources (Waters and Ravesloot 2001). Apaches moved into southwestern Arizona in the 1680s and 1690s and, unlike prior inhabitants of the Southwest, they utilized both valley bottoms and upland forests (Bahre 1991). Spanish settlers began moving into the region in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and by the 1600s, they had established settlements around missions near major rivers including the San Pedro, Santa Cruz, Magdalena, and the Rio Sonora (Clemensen 1987). Demand for timber for construction and fuel in the new settlements had a considerable impact on the surrounding forests (Bahre and Hutchinson 1985). However, the presence of Apache groups restricted Euro-American settlement in and around high-elevation forests of the Sky Islands until the end of the nineteenth century (Bigelow Jr 1968).

After the Gadsden Purchase in 1853, the region was divided and the current political borders were established; around this time, the arrival of the Southern Pacific Railroad and subjugation of the Apaches led to an increase in Euro-American settlement that brought about significant land use changes (Bahre 1991). Between 1902 and 1907, several federal forest reserves were established in the Sky Islands of Arizona and New Mexico (Allen 1989). Following the historic fires of 1910 in the western US, federal land management agencies adopted aggressive fire suppression policies (Pyne 1982). In 1935, the US Forest Service established the “10 a.m. policy,” with the goal of suppressing every fire by 10 a.m. the day following its initial report. Fire suppression became even more effective after the Second World War with advancement in firefighting technologies, particularly more abundant aircraft and fire suppressing chemicals.

In northern Mexico, many of the Sky Island forests were part of privately owned haciendas until the Mexican Revolution (1910 to 1920) and the passing of the Agrarian Code in 1934, which reallocated private lands to local communities, called “ejidos” (Thoms and Betters 1998). Unlike in the United States where much of the forest land was federally managed, under the ejido system, local communities were responsible for managing forests and wildfires; therefore, wildfires in northern Mexico were not suppressed to the same extent that they were in the western US. During the 1980s, the forest service of Mexico, aided by the US Forest Service and US Agency for International Development (USAID), developed a more active fire management program (Rodriguez-Trejo et al. 2011); however, the scale of firefighting in Mexico during that period was much smaller, with Mexico spending around one tenth of the dollar amount per acre on wildland firefighting activities compared to the US (Villarreal and Yool 2008).

Fire history

Prior to the twentieth century, wildfires within the Madrean Sky Islands were relatively common, particularly at higher elevations where greater productivity created abundant fuels and a dry pre-monsoon period allowed these fuels to cure and then burn (Baisan and Swetnam 1990). Tree-ring based fire history studies have found that, prior to the 1900s, pine-dominated sites experienced, on average, large fires every 6 to 15 years (Swetnam et al. 2001, Meunier et al. 2014). Mixed-conifer sites, on the other hand, experienced large fires less frequently at intervals ranging from 8 to 25 years (Swetnam and Baisan 1996, Iniguez et al. 2008, Margolis et al. 2011). While fire severity varied by site, fires in places historically dominated by pines were predominantly low severity (Swetnam et al. 2001, Iniguez et al. 2009).

Reduced wildfire activity in the mountains surrounding major human settlements has been documented for the US Sky Islands at the end of the nineteeth century (Baisan and Swetnam 1990, Swetnam et al. 2001). These changes have been associated with a sequence of historical events: the end of the Apache wars, the arrival of the railroad, and the introduction of large-scale livestock grazing. As a result, fine fuels required for fire spread were effectively removed over large areas (Savage and Swetnam 1990, Belsky and Blumenthal 1997).

North of the border, the last large wildfires prior to fire suppression occurred between 1900 and 1910; to the south, this process was delayed until the 1930s, following the Mexican Revolution (1910 to 1920). While some authors suggest that the allocation of ejidos marks the onset of fire suppression (Heyerdahl and Alvarado 2003), this is not the case for some sites in the Madrean Archipelago or even farther south (Kaib 1998, Cortés Montaño et al. 2012). However, in Mexico, the exclusion of wildfire was less extensive; in some more remote locations, frequent fires continued up to the present day (Fulé et al. 2011, Meunier et al. 2014). Moreover, some of these sites where fires still persist contain forest conditions similar to those believed to dominate the region prior to fire suppression (Cortés Montaño et al. 2012, Yocum Kent et al. 2017).

Fire identification with satellite imagery

Since information on dates and locations of many past fires was not available for the Sky Islands in Mexico, we used a semi-automated remote sensing fire-mapping approach to identify and delineate fires that occurred within the Mexican Sky Island mountain ranges. Our approach adapted satellite-based fire mapping and burn severity techniques used by MTBS in the US that are typically applied on an ad hoc basis, with knowledge of specific fire date and location (Monitoring Trends in Burn Severity: https://mtbs.gov/mapping-methods). The techniques take advantage of the changes in spectral information observed in remotely sensed imagery.

Post-fire mapping of burned area and severity are typically accomplished either through visual interpretation of aerial photography, or by using band-ratio techniques on satellite spectral information (White et al. 1996, Miller and Yool 2002, Lentile et al. 2006). Landsat multispectral imagery has proven suitable for fire mapping, as the data are relatively high resolution (30 m) with a 16-day return, and contain shortwave infrared (SWIR) and near infrared (NIR) information that can be used to discriminate a range of burn severity classes (White et al. 1996). The MTBS method uses Landsat data to identify fire perimeters and estimate burn severity classes using the differenced Normalized Burn Ratio (dNBR) method (Eidenshink et al. 2007). The Normalized Burn Ratio (NBR) is derived from the near infrared reflectance in Landsat band 4 (0.63 to 0.69 μm) and shortwave infrared reflectance in band 7 (2.08 to 2.35 μm) from a single Landsat image (Cocke et al. 2005, Key 2006), and the dNBR is a simple differencing of pre- and post-fire NBRs. The NBR equation is as follows:

An important aspect of the dNBR is careful selection of pre- and post-fire images to reduce error introduced by changes in scene conditions, including vegetation phenology and climate-induced conditions (Key 2006). Land surface and atmospheric conditions such as snow, vegetation change in wet versus dry seasons, shadows, smoke, and clouds all affect the outcome of the dNBR product (Key 2006).

The two steps of our semi-automated process were as follows: the first step involved calculating the NBR for a spring or early summer (assumed to be pre-fire) and a fall or early winter (assumed to be post-fire) Landsat scene of each year (1985 to 2011), calculating a dNBR with the two NBRs, then applying a dNBR threshold to identify locations where vegetation change was likely due to fire and to eliminate many non-fire related pixel changes (Prickett 2013). To calculate the dNBRs, we obtained 1517 cloud free Landsat 5 TM images (1985 to 2011) from the USGS Global Visualization Viewer (GLOVIS) website for seven Landsat path or row designations that cover the Madrean Archipelago Ecoregion. All images were corrected for atmospheric effects and haze, and converted to reflectance using the ATmospheric CORrection (ATCOR) module for ERDAS Imagine. The dNBR-derived detections were then filtered by size (<100 ha) and location (intersecting Sky Island polygons) to remove small non-fire vegetation changes (e.g., changes from productive agricultural fields to fallow), and positive identifications were converted to polygons. An initial accuracy assessment of fire detections tested against MODIS Fire Information for Resource Management System (FIRMS) daily detections (from 2001 to 2011) indicated that the automated process correctly identified about 42% of the fires in Mexico during this period.

The second step involved manually identifying additional fires in Mexico through visual interpretation using a combination of dNBR images and false color composites (displaying bands 6, 4, and 3 in RGB) from the full Landsat archive. Once identified, fire perimeters were digitized on screen using the dNBR and post-fire color composites. To assess omission errors that may have occurred due to data limitations (e.g., too many cloudy scenes during post-fire period to detect fire scar), we validated the burn perimeter data with MODIS FIRMS daily detections from 2001 to 2011. We also validated MTBS fires in the US with the FIRMS dataset to identify any commission errors in that dataset and to better ensure comparability of fire regimes across the region from different data sources and methods.

Derived and ancillary datasets

Using the fire perimeter polygons (rasterized using 100 m [1 ha] cell size), we developed a database of patch statistics for each fire, including those that overlap (Table 2). We selected a set of metrics that were representative of several attributes including size, shape, and orientation. The metrics allow characterization of fire patterns that may reflect underlying aspects of the environment or important ecological processes (Table 2).

To represent regional climate conditions through the study time period, we obtained the self-calibrating Palmer Drought Severity Index (scPDSI; van der Schrier et al. 2013). The scPDSI provides a standardized, time-integrated drought index that takes into account precipitation, temperature, and available moisture capacity of soils (van der Schrier et al. 2013). A variation of the original Palmer Drought Severity Index (Palmer 1965, Osborn et al. 2017), scPDSI was developed to provide more robust comparisons across diverse climates (van der Schrier et al. 2013). Approximately 80% of Sky Island fires occurred between the end of April and the beginning of August (Julian dates 117 to 221), so we selected April to represent pre-fire season conditions. At each fire polygon centroid, we extracted the April scPDSI value for the year that the fire burned. We adopted a standard classification of the index to interpret the results (for drought: extreme < −4; severe < −3; moderate < −2); wetter classes are assigned the same threshold values, but with positive sign (Palmer 1965, Osborn et al. 2017).

In addition, we used several datasets to represent spatial heterogeneity of environmental conditions, including those representing physical and biological factors that influence the occurrence of fire, as well as human presence and activities that affect ignition sources and use and management of fire (Table 3). We obtained a 30 m Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM; Farr et al. 2007) digital elevation model from Google Earth Engine (Gorelick et al. 2017) and resampled the data to 1 km resolution for computation of terrain ruggedness. The spatial climate data included 26 bioclim layers developed by the ClimateWNA project (Hamann et al. 2013) and were based on 1981 to 2010 climate normals (Table 3). Ignition source data were obtained from National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) (lightning; Albrecht et al. 2016); anthropogenic biomes (Ellis and Ramkutty 2008) and roads were downloaded from Commission for Environmental Cooperation (see CEC 2009). Population density data were obtained from Socioeconomic Data and Applications Center (SEDAC; http://sedac.ciesin.columbia.edu/). The lightning, roads, and population density data were smoothed by applying a uniformly weighted kernel (55 km radius window) before sampling. We used Brown and Lowe’s Biotic Communities of the Southwest (CBI 2004; available at http://databasin.org) to characterize variability in vegetation composition and structure (Brown et al. 1979).

Analysis

Characteristics of fire regimes

We used the fire perimeter database to characterize the regional and temporal distribution of fire frequency and area burned for each island and for each year during the study period. We mapped the variability in the landscape structure of fire patterns, including composition (area burned or fire size) and configuration (shape metrics) for each fire across the ecoregion.

Influence of climate on fire patterns

To understand how regional climate influences fire patterns, we used the R package (R Core Team 2017) ggplot2 (Wickham 2009) to generate a hexagon heatmap of two-dimensional bin counts (pattern metric by year) and graphed the results using a color gradient of scPDSI values. We specified 20 bins in horizontal and vertical dimensions for the plots. The position of each bin represents the center of mass (average of x, y values) for that bin and the mean scPDSI for the x, y values in each bin determines its color. The hexagon plots provided a visual tool to examine how fire size and shape varied in relation to wetter and drier years and whether patterns across years indicated trends during the study period.

Variation in fire patterns in relation to underlying spatial heterogeneity

We randomly sampled the study region within islands that experienced fire to obtain values for all spatial variables (Table 3). We applied a mask of fire perimeters to sample within areas that burned (total n = 6670; US n = 3699; Mexico n = 2971) and areas that did not burn (total n = 29 731; US n = 8759; Mexico n = 20 972). We used the sample data to conduct a graphical analysis of burned and unburned environments.

For categorical variables (anthropogenic biomes and biotic communities; see Table 3), we examined patterns in the data using stacked bar charts, for which height of the bar in each color represents its relative occurrence in burned and unburned samples. For continuous variables, we displayed the distribution of burned samples and unburned samples using smoothed density plots to aid in identifying the environmental space occupied by fires in the US and Mexico. We tested the null hypothesis that samples of burned and unburned environments came from a common population using Anderson-Darling statistics (AD.T; k-sample criterion AD; Scholz and Zhu 2016). Because several of the climate variables exhibited similar patterns, we included five of the 26 climate variables in the results, as well as population density, road density, terrain ruggedness, and lightning flash rate (Table 3).

Results

Validation of fire detections in US and Mexico

A total of 254 fires (>404 ha) were identified across the region from 1985 to 2011, 99 fires in Mexico and 155 in the US. (The fire perimeter database is available from US Geological Survey, see Villarreal and Poitras 2018). Of the 254 fires mapped, 142 occurred between 2001 and 2011 and were validated using MODIS FIRMS detections. All 142 fires were confirmed with FIRMS data (no false positives); however, the FIRMS data set contained six fires that were not mapped by MTBS or captured with our mapping approach for Mexico. Four of the missed fires were located in the US and two in Mexico. In all cases, the fires were not mapped because multiple consecutive post-fire Landsat scenes were obscured by clouds, making it impossible to accurately delineate a burn perimeter before regrowth occurred.

Characteristics of Sky Island fire regimes: number of fires and fire size

Mean fire size for all fires (254) during the period was 3847 ha (σ = 7262 ha), with similar mean fire size in Mexico and the US (3901 ha and 3808 ha, respectively). However, the range and variability in fire sizes differed between countries (Mexico σ = 5066 ha, maximum = 28 519 ha; US σ = 8368 ha, maximum = 91 476 ha). During our period of analysis, there were four distinct large fire years (1989, 1994, 2002, and 2011), each of which included more than 20 large fires and burned more than 75 000 ha yr−1, with a maximum of 231 249 ha burned in 2011 (Fig. 2). Fire patterns during some large fire years varied across the ecoregion; much of the fire activity and area burned in 1994 occurred in the US (Fig. 2) and, in 2011, the area burned in US Sky Islands was more than twice that of Mexico, with the Horseshoe II Fire (91 476 ha) in the Chiricahua Mountains contributing to that difference (Fig. 2). Over the entire study period, the Pan Duro, Huachuca-Patagonia, and Los Ajos-La Madera experienced the greatest number of fires (37, 25, and 21, respectively; Fig. 2). The Pan-Duro had the most hectares burned (136 530 ha), followed by the Chiricahua (116 004 ha) and Atascosa-Cibuta mountains (89 048 ha). When normalized as a percentage of total Sky Island area, the following Sky Islands had considerable area affected by fire: Animas Mountains (island area = 59 938 ha; total area burned = 84 414 ha), El Pinito (island area = 103 802 ha; total area burned = 69 334 ha), Chiricahua Mountains (island area = 180 217 ha; total area burned = 116 004 ha), Santa Catalina (island area = 85 317 ha; total area burned = 52 490 ha), and Huachuca-Patagonia (island area = 119 386 ha, total area burned = 60 424 ha) (Fig. 2).

Variation in spatial and temporal patterns of fire patch metrics

Maps of fire size and core area index (i.e., interior area of the fire, greater than 100 m from the fire perimeter as a percentage of fire size) indicate that many of largest fires and fires with considerable core area (>0.90) occurred along the border in the Atascosa-Cibuta, El Pinito, and Pan Duro mountains, and in the Chiricahua and Santa Catalina mountains in the US (Fig. 3). Eccentricity (i.e., ratio of the distance between the two farthest extremities of each fire and the distance of the maximum width of its perpendicular axis, or length-to-breadth ratio) was generally high for most fires (i.e., >0.6), indicating more elongated shapes. Shape index (i.e., fire shape complexity; the degree of departure from a circular shape; ranges from 1 [round] to >1 [complex]) varied widely by fire and range, but complexity tended to be higher for fires in Sky Islands on or adjacent to the border, and north of the border.

Distribution of fire patch patterns across the Sky Islands of the Madrean Ecoregion, US and Mexico, between 1985 and 2011: fire size and core area index (top row) and eccentricity and shape index (bottom row). Larger fires tended to have greater core area, but more circular (versus more elongated) patterns occurred across the region, as did fires with more or less core area relative to their size

Influence of regional climate

The scPDSI patterns indicated that drier and wetter pre-fire seasons generally alternated, but multiple, consecutive dry seasons (scPDSI < −2) became more frequent after year 2000 compared to earlier years (Fig. 4). Across years and in relation to climate, spatial patterns were heterogeneous, with a fairly wide range of metric values. Maximum fire size generally increased through time, and this trend was driven by several large fire events that occurred during the droughts of 2000 to 2003 and 2011 (Fig. 4a). Interior areas of fires reflected a lower range of values in early, wetter years (pre-fire season scPDSI > 2) and a clustering of higher values in recent, drier seasons with scPDSI < −2 (i.e., core area index; Fig. 4b). Shapes, overall, varied in complexity, but the upper range of values for Perimeter Area Ratio exhibited a decreasing trend across years with variable climate (Fig. 4c). More circular shapes, (i.e., shape index < 2) were common, but fires with highly complex shapes were less frequent across years and across variability in scPDSI (Fig. 4d). Recent, drier seasons (scPDSI < −2) produced some of the most complex shapes, but 2001, a year with wetter values (−2 < scPDSI > 2), particularly for some fires, also included complex shapes. Eccentricity, or the length-to-breadth ratio, indicated that many of the fires tended toward elongated, rather than circular, shapes (index value > 0.6; Fig. 4e). Bearing ranged from 23 to 73 degrees (north-northeast to east-northeast) for all fires (Fig. 4f); these values indicate the orientation of the two farthest extremities of each fire (Table 2).

Hexagon plots of two-dimensional bin counts (bins in horizontal and vertical directions = 20), representing pattern metric values (Table 2) by year for fires that burned between 1985 and 2011 in the Madrean Ecoregion Sky Island, US and Mexico. Metrics include: a) Fire size, b) Core area index, c) Perimeter area ratio, d) Shape index, e) Eccentricity and f) Bearing. The position of each bin represents the average of the x, y values assigned to the bin; bin color corresponds to the mean scPDSI for fires in the bin (orange to green scale represents drier to wetter conditions). Due to outliers, fire size is presented in log scale on the y-axis of Fig. 4a. Fires exhibited heterogeneity in spatial patterns across years and climates. In early time periods, fires occurred in a mixture of wetter and drier years, but after 2005, a majority of fires burned in years with moderate to severe drought conditions (scPDSI < −2)

Fire patterns and underlying spatial heterogeneity

Biotic communities that experienced fire occurred in different proportions to those in the unburned landscape (Fig. 5, top). A majority of the burned area occurred in Madrean Evergreen Woodlands and Petran Montane Conifer Forests; these communities occurred in greater proportion on burned versus unburned landscapes. Semidesert Grassland occupied a large proportion of unburned area, and a somewhat lesser proportion of burned landscapes. Unburned areas were predominantly Madrean Evergreen Woodlands and Semidesert Grassland with higher proportions of Arizona Upland Subdivision−Sonoran Desertscrub, Chihuahuan Desertscrub, and Sinaloan Thornscrub than burned landscapes.

Differences between burned and unburned areas within biotic communities (top) and anthropogenic biomes (bottom) of the Madrean Ecoregion Sky Islands, US and Mexico, between 1985 and 2011. Comparison of color bar height for each class allows identification of cases where fire occurred disproportionately with regard to biotic and human communities, relative to unburned landscapes

Burned and unburned landscapes also differed in anthropogenic biome composition (Fig. 5, bottom). The most noted contrast was in the higher proportion of burned Remote Forests, relative to its abundance in unburned landscapes. Populated Rangelands and Remote Rangelands were less commonly burned than unburned; Villages and Residential anthromes composed a small proportion of the study region, with no evident difference in their occurrence on burned and unburned areas.

Burned areas occupied distinct environments within their unburned context based on visual interpretation of smoothed density plots (Fig. 6) and results of statistical tests (AD.T P-value < 0.001 for all burned-unburned comparisons; see Appendix). Results for the climate variables indicated that fire environments occurred at the lower to mid-range of heat moisture in both countries, corresponding to a somewhat higher range of mean annual precipitation and lower range in mean annual temperature (Fig. 6a−c). Fires occurred more often in places with later onset of the frost-free period; this trend was observed in both countries, but the density plot for burned samples was particularly skewed toward later Julian dates for Mexico (Fig. 6d). Burned areas were coincident with a higher range in mean summer precipitation in the US, but the peak in burned sample density occurred at a slightly lower value for mean summer precipitation (MSP) than the unburned maximum density in Mexico (Fig. 6e).

The smoothed density plots illustrate the distribution of area burned (orange) relative to unburned environments (gray) in the Madrean Ecoregion Sky Islands that experienced fire in the time period of the study (1985 to 2011). Variables considered were: a) Annual heat moisture index, b) Mean annual precipitation, c) Mean annual temperature, d) Beginning of frost-free period, e) Mean summer precipitation, f) Lightning flash rate, g) Population density, h) Road density, and i) Terrain ruggedness index. The top graph for each variable was constructed from random points in US burned−unburned locations; the bottom graph used a set of random points for Mexico. Test comparisons indicated rejection of the null hypothesis that burned−unburned samples came from a common distribution (AD.T P-value < 0.001)

Natural ignitions did not limit the occurrence of fire, based on the smoothed density plots for US and Mexico (Fig. 6f). Specifically, burned environments were located in the lower range of values for lightning flash rate, as well as in places where rates of lightning strikes were higher. Areas in Mexico with the highest flash rates had lower density of area burned or remained unburned. Population density smoothed plots for burned−unburned samples indicated that fires occurred in very remote areas, as well as more populated areas (Fig. 6g). In Mexico, greater density of unburned samples occurred in sparsely populated areas, compared to burned samples. Burned environments included places with a wide range of road density, especially in the moderate to high range, but in both countries, fires were limited where roads were most prevalent (Fig. 6h). Burned environments were located in flatter, as well as more complex terrain; burned sample distributions tended to encompass places with higher values of terrain ruggedness index for both countries, compared to unburned (Fig. 6i).

Discussion

Characteristics of contemporary fire regimes

Recent fires in the Madrean Ecoregion exhibited several distinctive spatial and temporal patterns. Area burned varied by year and across islands (Fig. 2), but generally increased over the study period, culminating with the 2011 fire year, when the Horseshoe II Fire burned much of the Chiricahua Mountain range in Arizona (91 476 ha), and the El Pinito (28 519 ha) and Murphy Complex fires (26 044 ha) burned along the international border. Fire size in the US was more variable than in Mexico, and much of that variability was related to several large twenty-first century fires. In general, Sky Islands near the border had the greatest number of fires during the period (Pan Duro, 37; Huachuca-Patagonia, 25; and Los Ajos-Madera, 21), and many of the large border fires exhibited complex shapes. As proportion of Sky Island size, the fires in the US tended to burn more area, especially in the Animas, Chiricahua, Huachuca, and Santa Catalina mountains. Many of the southern islands in Mexico had only a few small fires during the study period. The pattern of larger fires north of the international border may be related to observed increases in forest fuel loads at the stand level and related fuel homogeneity at landscape levels due to a longer period of fire exclusion (Moore et al. 2004).

Climate and topographic influence on fire patterns

We found that, during our study period, the number of fires and area burned were greatest during drought years identified in other studies (e.g., Dillon et al. 2011; Fig. 2). In particular, 1989, 1994, 2002, and 2011 stand out as large fire years, with at least 20 fires (>404 ha) and more than 75 000 ha burned each year. However, we found that fire size and complexity were highly variable in relation to scPDSI, suggesting that fires increased landscape heterogeneity through a range of variation in fire shape and size in years with a mixture of drier and wetter pre-fire seasons (Fig. 4). But we also observed that larger fire sizes followed trends of drought and increased temperature across the region, a trend that is already affecting the distribution of plants in the Sky Islands along an elevational gradient (Brusca et al. 2013). The strong relationship between drought and fire was notable for the Sky Islands in the southwestern part of the ecoregion in Mexico: 12 of the 13 total fires in four Sky Islands (Aconchi, El Carmen-Verde, La Huerta, and La Madera-Cucurpe) occurred during 1989, 1994, 2002, and 2011; however, these fires were generally of moderate size (μ = 2911 ha).

A number of studies in the American Southwest have documented the strong historical relationship between wildfire and antecedent climate (Swetnam and Betancourt 1998, Crimmins and Comrie 2004). Although similar studies that include the Mexican Sky Islands are not as common, a recent study by Meunier et al. (2014) in the Sierra San Luis found that, prior to 1886, drought years during the fire year were most conducive for fires. After 1887, in remote areas that continued to burn, the pattern appears to shift and wet conditions the year prior to the fire become a more important factor (Meunier et al. 2014). This suggests that wet years result in increased biomass and fuel production that then cures a year later and supports the ignition and spread of fires. Because patterns of scPDSI varied considerably across our study region, the relationship between scPDSI and fires was complex. There is a need to more closely investigate these relationships to better understand how antecedent climate and drought influence the geographic patterns of fire across the Madrean Archipelago region.

Vegetation type and fuel moisture content are driven by elevation and topography that create gradients of temperature, precipitation, and evaporation, thus defining unique fire environments and associated fire regimes (Mansuy et al. 2014, Meunier et al. 2014, Perez-Verdin et al. 2014, Whitman et al. 2015). Our results suggest that many of the fire patterns observed in the Madrean Sky Islands occurred at higher elevations with cooler temperatures, received slightly more precipitation, and had fewer frost-free days than sites that remained unburned (Fig. 6a−d). These areas are dominated by Madrean Evergreen Woodlands and Petran Montane Conifer Forests biotic communities that burned in greater proportion on burned versus unburned landscapes (Fig. 5). Historically, these vegetation types produced enough fuels to support surface fires every 8 to 15 years in these middle-elevation forests; higher-elevation forests characterized by longer fire intervals occurred in proportions that were comparable to that of unburned landscapes (Fig. 5). The largest fires we observed were on the US side of the border, including the Horseshoe II Fire and the 2003 Aspen Fire in the Santa Catalinas (32 231 ha). These large fires may represent the interactive effects of regional climate and, in some places, a longer history of fire suppression on fuel accumulation and connectivity (Miller et al. 2009).

Human influence on the regional variability of spatial patterns

The importance of understanding the various influences of human activity on fire regimes is increasingly recognized (Mann et al. 2016, Parisien et al. 2016) and takes on a unique relevance in areas where livelihoods are closely dependent on the use of fire (Perez-Verdin et al. 2014). Our geographic analysis revealed patterns of fire activity, size, and shape that are likely related to social and cultural dynamics. First, the data indicate greater fire activity surrounding the international border. Specifically, number of fires and area burned was greatest on some of the Sky Islands that traverse the border or are adjacent to it, particularly the Peloncillo-Pan Duro, Huachuca-Patagonia, and Atascosa-Cibuta ranges. This pattern is likely associated with greater human-caused ignitions along major travel corridors. Two of the largest fires that burned during dry 2011, the Horseshoe II Fire and Murphy Complex, were determined to be human-caused by the US Forest Service. Some unique fire patches and patterns occurred near the international border where lack of fuel continuity along the border access road or direct fire suppression resulted in long, straight fire perimeter edges adjacent to the boundary line. These uniquely shaped border fires were characterized by high eccentricity index values (i.e., long and thin) and had strong east to west bearings. Alternatively, fires can be oriented in a particular direction due to prevailing winds during burning, or corresponding to topographic characteristics (Barros et al. 2013).

Secondly, population density was generally similar between burned and unburned sites, with a greater distribution of fires in the low population density range, but with a somewhat bimodal distribution showing a slight increase in fires occurring in the high population density range, indicating the influence of land use and anthropogenic activities on fires for some Sky Islands (Fig. 6g). Remote forests experienced proportionately more fire, suggesting that wildfires dominate the fire regime, rather than human use of fire in agricultural practices (i.e., in Populated Forests; Fig. 5; Perez-Verdin et al. 2014). Furthermore, natural ignition source (i.e., lightning strikes; Fig. 6f) did not limit the occurrence of fire, but areas in the southern Sky Islands with highest strike rate experienced less fire, possibly due to more mesic vegetation types and higher fuel moisture in those islands that receive more precipitation from the south.

Research implications and research needs

Dendrochronological fire scar evidence from many sites in northwestern Mexico shows that some forests have maintained historical fire regimes (Kaib 1998, Stephens et al. 2003, Yocum Kent et al. 2017) and can become reference sites for Western forests in the US that experienced long-term suppression (Leopold 1937, Fulé et al. 2012, Meunier et al. 2014), potentially guiding ecological restoration of altered sites (Stephens and Fulé 2005). Future research on modern fires in the Madrean Sky Islands could more directly consider the role of historical land use, forest management, and climate on fire attributes in this region. For example, the fire regional severity data (i.e., dNBR) that we developed to map fire perimeters, as measured using pre- and post-fire differencing of satellite imagery, could be used to examine the role of climate, fire weather, management history, and active fire management (e.g., back burns) in resulting spatial heterogeneity of severity patterns. Research into land use history of individual Sky Islands would help to elucidate these possible effects, as would more stand-level field data describing historical fire regimes and current forest structure in sites with different fire histories in northern Mexico.

Conclusions

The purpose of this research was to fill a significant information gap on recent wildfire activity across the bi-national Madrean Archipelago Ecoregion of the United States and Mexico. Past fire research in this region, in particular tree-ring research, suggests that different fire regimes observed in mountains of the US and Mexico were linked to historical land use and fire suppression activities. Understanding the links between these environmental histories and contemporary fire regimes of the Sky Islands can help to guide regional fire planning, fuels management, and habitat conservation efforts on both sides of the US−Mexico border.

Our results show increasing fire sizes across the region, particularly in Sky Islands of the US, with large fires occurring during recent twenty-first century droughts. Area burned generally increased over the study period, culminating with the 2011 fire year, when the Horseshoe II Fire burned much of the Chiricahua Mountain range in Arizona. Number of fires and area burned were greatest on some of the mountains that traverse the border or are adjacent to it, suggesting that recent fire patterns in this area are strongly influenced by patterns of human activity. Two of the largest fires that burned during our study period, the Horseshoe II Fire and Murphy Complex, were determined to be human-caused by the US Forest Service and occurred during the dry 2011 fire season. Given projections of increasing temperature and decreasing precipitation (Wilder et al. 2013), along with projections of continued human population growth (Villarreal et al. 2013) in the borderlands region, large and more frequent fires may become more common in the future. Further analyses of fire occurrence and fire severity in the context of interactions among past and current land uses, regional and local climate variables, and fuel conditions can provide additional important information when considering scenarios of possible future fire regimes in this biologically and culturally diverse region.

Our research provides insight into the modern fire regimes of mountains in the Madrean Archipelago Ecoregion, an area that previously lacked cross-border fire information. A major obstacle to our understanding of the connectivity of ecological, hydrologic, and socio-cultural systems in this region is geospatial data that adhere to political boundaries rather natural ecological or physical boundaries. Recent research on ecosystem service flows in the US−Mexico borderlands highlights the challenges and importance of a transboundary approach (López-Hoffman et al. 2010, Norman et al. 2012, Norman et al. 2013). Transboundary data are particularly important to consider when managing habitat for migratory species and large predators (e.g., Panthera onca, Linnaeus; McCain and Childs 2008, Atwood et al. 2011), and for many other ecological processes that are not confined to political boundaries. An increased focus on developing and sharing transboundary datasets can contribute to collaborative research efforts between countries that improve knowledge about ecological patterns and processes in the borderlands, and support long-term regional planning and restoration efforts.

References

Albrecht, R.I., S. Goodman, D. Buechler, R. Blakeslee, and H Christian. 2016. LIS 0.1 Degree very high resolution gridded lightning full climatology (VHRFC). Dataset available online from the NASA Global Hydrology Resource Center DAAC, Huntsville, Alabama, USA. https://doi.org/10.5067/LIS/LIS/DATA301. Accessed 30 May 2018.

Allen, L.S. 1989. Livestock and the Coronado National Forest. Rangelands 11: 14–20.

Atwood, T.C., J.K. Young, J.P. Beckmann, S.W. Breck, J. Fike, O.E. Rhodes, and K.D. Bristow. 2011. Modeling connectivity of black bears in a desert sky island archipelago. Biological Conservation 144: 2851–2862 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2011.08.002.

Bahre, C.J. 1991. A legacy of change: historic human impact on vegetation in the Arizona borderlands. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

Bahre, C.J., and C.F. Hutchinson. 1985. The impact of historic fuelwood cutting on the semidesert woodlands of southeastern Arizona. Forest and Conservation History 29: 175–186 https://doi.org/10.2307/4004712.

Baisan, C.H., and T.W. Swetnam. 1990. Fire history on a desert mountain range: Rincon Mountain Wilderness, Arizona, USA. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 20: 1559–1569 https://doi.org/10.1139/x90-208.

Baker, W.L. 2013. Is wildland fire increasing in sagebrush landscapes of the western United States? Annals of the Association of American Geographers 103: 5–19 https://doi.org/10.1080/00045608.2012.732483.

Barros, A., J. Pereira, M. Moritz, and S. Stephens. 2013. Spatial characterization of wildfire orientation patterns in California. Forests 4: 197–217 https://doi.org/10.3390/f4010197.

Belsky, A.J., and D.M. Blumenthal. 1997. Effects of livestock grazing on stand dynamics and soils in upland forests of the Interior West. Efectos del pastoreo sobre la dinamica de arboles y suelos en bosques en el altiplano del occidente interior. Conservation Biology 11: 315–327 https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-1739.1997.95405.x.

Bergeron, Y., M. Flannigan, S. Gauthier, A. Leduc, and P. Lefort. 2004. Past, current and future fire frequency in the Canadian boreal forest: implications for sustainable forest management. AMBIO 33: 356–360 https://doi.org/10.1579/0044-7447-33.6.356.

Bigelow, J., Jr. 1968. On the bloody trail of Geronimo. Los Angeles: Westernlore Press.

Bond, W.J., and J.E. Keeley. 2005. Fire as a global “herbivore”: the ecology and evolution of flammable ecosystems. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 20: 387–394 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2005.04.025.

Brown, D.E., C.H. Lowe, and C.P. Pase. 1979. A digitized classification system for the biotic communities of North America, with community (series) and association examples for the Southwest. Arizona Nevada Academy of Science 14: 1–16 http://www.jstor.org/stable/40025041.

Brusca, R.C., J.F. Wiens, W.M. Meyer, J. Eble, K. Franklin, J.T. Overpeck, and W. Moore. 2013. Dramatic response to climate change in the Southwest: Robert Whittaker’s 1963 Arizona mountain plant transect revisited. Ecology and Evolution 3: 3307–3319 https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.720.

Bui R, Buliung RN, Remmel TK. 2012. aspace: a collection of functions for estimating centrographic statistics and computational geometries for spatial point patterns. R package version 3.2. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=aspace. Accessed 30 May 2018.

Burton, P.J., M.A. Parisien, J.A. Hicke, R.J. Hall, and J.T. Freeburn. 2009. Large fires as agents of ecological diversity in the North American boreal forest. International Journal of Wildland Fire 17: 754–767 https://doi.org/10.1071/wf07149.

Cannon, S.H., J.E. Gartner, M.G. Rupert, J.A. Michael, A.H. Rea, and C. Parrett. 2010. Predicting the probability and volume of postwildfire debris flows in the intermountain western United States. GSA Bulletin 122 (1-2): 127–144.

CBI (Conservation Biology Institute). 2004. Digital representation of Brown and Lowe’s 1979 map Biotic Communities of the Southwest. https://databasin.org/maps/new#datasets=e8e241e869054d7e810894e5e993625e. Accessed 30 May 2018.

CEC (Commission for Environmental Cooperation). 2008. Anthropogenic biomes. http://www.cec.org/tools-and-resources/map-files/anthropogenic-biomes. Accessed 30 May 2018.

CEC (Commission for Environmental Cooperation). 2009. Roads. http://www.cec.org/tools-and-resources/map-files/major-roads-2009. Accessed 30 May 2018.

Clemensen, A.B. 1987. Cattle, copper, and cactus: the history of Saguaro National Monument, AZ historic resource study, Saguaro National Monument. Denver: US Department of the Interior, National Park Service.

Coblentz, D.D., and K.H. Riitters. 2004. Topographic controls on the regional-scale biodiversity of the south-western USA. Journal of Biogeography 31: 1125–1138 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2699.2004.00981.x.

Cocke, A.E., P.Z. Fulé, and J.E. Crouse. 2005. Comparison of burn severity assessments using Differenced Normalized Burn Ratio and ground data. International Journal of Wildland Fire 14: 189 https://doi.org/10.1071/wf04010.

Cortés Montaño, C., P.Z. Fulé, D.A. Falk, J. Villanueva-Díaz, and L.L. Yocom. 2012. Linking old-growth forest composition, structure, fire history, climate and land-use in the mountains of northern México. Ecosphere 3: 1–16 https://doi.org/10.1890/es12-00161.1.

Crimmins, M.A., and A.C. Comrie. 2004. Interactions between antecedent climate and wildland fire variability across south-eastern Arizona. International Journal of Wildland Fire 13: 455–466 https://doi.org/10.1071/WF03064.

Dillon, G.K., Z.A. Holden, P. Morgan, M.A. Crimmins, E.K. Heyerdahl, and C.H. Luce. 2011. Both topography and climate affected forest and woodland burn severity in two regions of the western US, 1984 to 2006. Ecosphere 2: 1–33 https://doi.org/10.1890/es11-00271.1.

Eidenshink, J., B. Schwind, K. Brewer, Z.-L. Zhu, B. Quayle, and S. Howard. 2007. A project for Monitoring Trends in Burn Severity. Fire Ecology 3: 3–21 https://doi.org/10.4996/fireecology.0301003.

Ellis, E.C., and N. Ramankutty. 2008. Putting people in the map: anthropogenic biomes of the world. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 6: 439–447 https://doi.org/10.1890/070062.

Farr, T.G., P.A. Rosen, E. Caro, R. Crippen, R. Duren, S. Hensley, M. Kobrick, M. Paller, E. Rodriguez, L. Roth, and D. Seal. 2007. The shuttle radar topography mission. Reviews of Geophysics 45 (2): RG2004 https://doi.org/10.1029/2005RG000183.

Fulé, P.Z., M. Ramos-Gómez, C. Cortés Montaño, and A.M. Miller. 2011. Fire regime in a Mexican forest under indigenous resource management. Ecological Applications 21: 764–775 https://doi.org/10.1890/10-0523.1.

Fulé, P.Z., L.L. Yocom, C.C. Montaño, D.A. Falk, J. Cerano, and J. Villanueva-Díaz. 2012. Testing a pyroclimatic hypothesis on the Mexico–United States border. Ecology 93: 1830–1840 https://doi.org/10.1890/11-1991.1.

Gorelick, N., M. Hancher, M. Dixon, S. Ilyushchenko, D. Thau, and R. Moore. 2017. Google Earth Engine: planetary-scale geospatial analysis for everyone. Remote Sensing of Environment 202: 18–27 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2017.06.031.

Haire, S.L., and K. McGarigal. 2009. Changes in fire severity across gradients of climate, fire size, and topography: a landscape ecological perspective. Fire Ecology 5: 86–103 https://doi.org/10.4996/fireecology.0502086.

Hamann, A., T. Wang, D.L. Spittlehouse, and T.Q. Murdock. 2013. A comprehensive, high-resolution database of historical and projected climate surfaces for western North America. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 94: 1307–1309 https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-12-00145.1.

Heyerdahl, E.K., and E. Alvarado. 2003. Influence of climate and land use on historical surface fires in pine–oak forests, Sierra Madre Occidental, Mexico. Fire and climatic change in temperate ecosystems of the western Americas ecological studies. In Fire and climatic change in temperate ecosystems of the western Americas, ed. T.T. Veblen, 196–217. New York: Springer.

Hijmans RJ (2016) geosphere: spherical trigonometry. R package version 1.5-5. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=geosphere. Accessed 30 May 2018.

Hurteau, M.D., J.B. Bradford, P.Z. Fulé, A.H. Taylor, and K.L. Martin. 2014. Climate change, fire management, and ecological services in the southwestern US. Forest Ecology and Management 327: 280–289 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2013.08.007.

Hurteau, M.D., and M.L. Brooks. 2011. Short- and long-term effects of fire on carbon in US dry temperate forest systems. BioScience 61: 139–146 https://doi.org/10.1525/bio.2011.61.2.9.

Hutto, R.L., R.E. Keane, R.L. Sherriff, C.T. Rota, L.A. Eby, and V.A. Saab. 2016. Toward a more ecologically informed view of severe forest fires. Ecosphere 7 (2): e01255 https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.1255.

Iniguez, J.M., J.L. Ganey, P.J. Daugherty, and J.D. Bailey. 2005. Using cluster analysis and a classification and regression tree model to developed cover types in the sky islands of southeastern Arizona. In Connecting mountain islands and desert seas: biodiversity and management of the Madrean Archipelago II, USDA Forest Service Proceedings RMRS-P-36, Rocky Mountain Research Station, ed. G.J. Gottfried, B.S. Gebow, L.G. Eskew, and C.B. Edminster, 195–200. Fort Collins.

Iniguez, J.M., T.W. Swetnam, and C.H. Baisan. 2009. Spatially and temporally variable fire regime on Rincon Peak, Arizona, USA. Fire Ecology 5: 3–21 https://doi.org/10.4996/fireecology.0501003.

Iniguez, J.M., T.W. Swetnam, and S.R. Yool. 2008. Topography affected landscape fire history patterns in southern Arizona, USA. Forest Ecology and Management 256: 295–303 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2008.04.023.

Kaib, M.J. 1998. Fire history in riparian canyon pine–oak forests and the intervening desert grasslands of the Southwest borderlands: a dendrochronological, historical, and cultural inquiry. Tucson: Thesis, University of Arizona.

Key, C.H. 2006. Ecological and sampling constraints on defining landscape fire severity. Fire Ecology 2: 34–59 https://doi.org/10.4996/fireecology.0202034.

Lentile, L.B., Z.A. Holden, A.M.S. Smith, M.J. Falkowski, A.T. Hudak, P. Morgan, S.A. Lewis, P.E. Gessler, and N.C. Benson. 2006. Remote sensing techniques to assess active fire characteristics and post-fire effects. International Journal of Wildland Fire 15: 319–345 https://doi.org/10.1071/wf05097.

Leopold, A. 1937. Conservationists in Mexico. American Forests 37: 118–120.

Liu, J., T. Dietz, S.R. Carpenter, C. Folke, M. Alberti, C.L. Redman, S.H. Schneider, E. Ostrom, A.N. Pell, J. Lubchenco, and W.W. Taylor. 2007. Coupled human and natural systems. AMBIO 36: 639–649.

López-Hoffman, L., R.G. Varady, K.W. Flessa, and P. Balvanera. 2010. Ecosystem services across borders: a framework for transboundary conservation policy. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 8: 84–91 https://doi.org/10.1890/070216.

Mann, M.L., E. Batllori, M.A. Moritz, E.K. Waller, P. Berck, A.L. Flint, L.E. Flint, and E. Dolfi. 2016. Incorporating anthropogenic influences into fire probability models: effects of human activity and climate change on fire activity in California. PLoS One 11 (14): e0153589 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0153589.

Mansuy, N., Y. Boulanger, A. Terrier, S. Gauthier, A. Robitaille, and Y. Bergeron. 2014. Spatial attributes of fire regime in eastern Canada: influences of regional landscape physiography and climate. Landscape Ecology 29: 1157–1170 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-014-0049-4.

Margolis, E.Q., T.W. Swetnam, and C.D. Allen. 2011. Historical stand-replacing fire in upper montane forests of the Madrean Sky Islands and Mogollon Plateau, southwestern USA. Fire Ecology 7: 88–107 https://doi.org/10.4996/fireecology.0703088.

McCain, E.B., and J.L. Childs. 2008. Evidence of resident jaguars (Panthera onca) in the southwestern United States and the implications for conservation. Journal of Mammalogy 89: 1–10 https://doi.org/10.1644/07-mamm-f-268.1.

McLaughlin, S. 1994. An overview of the flora of the sky islands, southeastern Arizona: diversity, affinities, and insularity. In Biodiversity and management of the Madrean Archipelago: the sky islands of southwestern United States and northwestern Mexico, USDA Forest Service General Technical Report RM-GTR-264, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station, Fort Collins, Colorado, USA, ed. L.H. Debano, P.H. Ffolliott, A. Ortega-Rubio, G.J. Gottfried, R.H. Hamre, and C.B. Edminster, 60–70.

Meunier, J., W.H. Romme, and P.M. Brown. 2014. Climate and land-use effects on wildfire in northern Mexico, 1650–2010. Forest Ecology and Management 325: 49–59 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2014.03.048.

Miller, J.D., B.M. Collins, J.A. Lutz, S.L. Stephens, J.W. van Wagtendonk, and D.A. Yasuda. 2012b. Differences in wildfires among ecoregions and land management agencies in the Sierra Nevada region, California, USA. Ecosphere 3 (9): 1–20 https://doi.org/10.1890/es12-00158.1.

Miller, J.D., H.D. Safford, M. Crimmins, and A.E. Thode. 2009. Quantitative evidence for increasing forest fire severity in the Sierra Nevada and southern Cascade Mountains, California and Nevada, USA. Ecosystems 12: 16–32 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-008-9201-9.

Miller, J.D., C.N. Skinner, H.D. Safford, E.E. Knapp, and C.M. Ramirez. 2012a. Trends and causes of severity, size, and number of fires in northwestern California, USA. Ecological Applications 22: 184–203 https://doi.org/10.1890/10-2108.1.

Miller, J.D., and S.R. Yool. 2002. Mapping forest post-fire canopy consumption in several overstory types using multi-temporal Landsat TM and ETM data. Remote Sensing of Environment 82: 481–496 https://doi.org/10.1016/s0034-4257(02)00071-8.

Moore, M.M., D.W. Huffman, P.Z. Fulé, W.W. Covington, and J.E. Crouse. 2004. Comparison of historical and contemporary forest structure and composition on permanent plots in Southwestern ponderosa pine forests. Forest Science 50: 162–176.

Morgan, P., C.C. Hardy, T.W. Swetnam, M.G. Rollins, and D.G. Long. 2001. Mapping fire regimes across time and space: understanding coarse and fine-scale fire patterns. International Journal of Wildland Fire 10: 329–342 https://doi.org/10.1071/WF01032.

Niering, W.A., and C.H. Lowe. 1984. Vegetation of the Santa Catalina Mountains: community types and dynamics. Vegetatio 58: 3–28 https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00044893.

Norman, L., M. Villarreal, R. Niraula, T. Meixner, G. Frisvold, and W. Labiosa. 2013. Framing scenarios of binational water policy with a tool to visualize, quantify and valuate changes in ecosystem services. Water 5: 852–874 https://doi.org/10.3390/w5030852.

Norman, L.M., M.L. Villarreal, F. Lara-Valencia, Y. Yuan, W. Nie, S. Wilson, G. Amaya, and R. Sleeter. 2012. Mapping socio-environmentally vulnerable populations access and exposure to ecosystem services at the US–Mexico borderlands. Applied Geography 34: 413–424 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2012.01.006.

Notaro, M., A. Mauss, and J.W. Williams. 2012. Projected vegetation changes for the American Southwest: combined dynamic modeling and bioclimatic-envelope approach. Ecological Applications 22: 1365–1388 https://doi.org/10.1890/11-1269.1.

Omernik, J.M. 1987. Ecoregions of the conterminous United States. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 77: 118–125 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8306.1987.tb00149.x.

Osborn, T.J., J. Barichivich, I. Harris, G. van der Schrier, and P.D. Jones. 2017. Hydrological cycle: monitoring global drought using the self-calibrating Palmer Drought Severity Index. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 97 (8): S32–S33.

Palmer, W.C. 1965. Meteorological drought. Research Paper No. 45. Office of Climatology, United States Weather Bureau. Washington, D.C., USA.

Parisien, M.A., C. Miller, S.A. Parks, E.R. Delancey, F.-N. Robinne, and M.D. Flannigan. 2016. The spatially varying influence of humans on fire probability in North America. Environmental Research Letters 11: 075005 https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/11/7/075005.

Parisien, M.A., V.S. Peters, Y. Wang, J.M. Little, E.M. Bosch, and B.J. Stocks. 2006. Spatial patterns of forest fires in Canada, 1980–1999. International Journal of Wildland Fire 15: 361–374 https://doi.org/10.1071/WF06009.

Perez-Verdin, G., M.A. Marquez-Linares, and M. Salmeron-Macias. 2014. Spatial heterogeneity of factors influencing forest fires size in northern Mexico. Journal of Forest Research 25: 291–300 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11676-014-0460-3.

Petrakis, R.E., M.L. Villarreal, Z. Wu, R. Hetzler, B.R. Middleton, and L.M. Norman. 2018. Evaluating and monitoring forest fuel treatments using remote sensing applications in Arizona, USA. Forest Ecology and Management 413: 48–61 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2018.01.036.

Prickett, J.K. 2013. Developing a methodology for mass-identification of historical wildfires in northern Mexico using Landsat Thematic Mapper imagery. Tucson: Thesis, University of Arizona.

Pyne, S.J. 1982. Fire in America: a cultural history of wildland and rural fire. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

R Core Team. 2017. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

Riding, A. 1989. Distant neighbors: a portrait of the Mexicans. New York: Vintage Press.

Rodríguez-Trejo, D.A. 2008. Fire regimes, fire ecology, and fire management in Mexico. AMBIO 37: 548–556 https://doi.org/10.1579/0044-7447-37.7.548.

Rodríguez-Trejo, D.A., P.A. Martínez-Hernández, H. Ortiz-Contla, M.R. Chavarría-Sánchez, and F. Hernández-Santiago. 2011. The present status of fire ecology, traditional use of fire, and fire management in Mexico and Central America. Fire Ecology 7: 40–56 https://doi.org/10.4996/fireecology.0701040.

Savage, M., and T.W. Swetnam. 1990. Early 19th-century fire decline following sheep pasturing in a Navajo ponderosa pine forest. Ecology 71: 2374–2378 https://doi.org/10.2307/1938649.

Scholz, F., and A. Zhu. 2016. kSamples: K-Sample Rank Tests and their Combinations. R package version 1: 2–4 https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=kSamples. Accessed 30 May 2018.

Schrier, G.V.D., J. Barichivich, K.R. Briffa, and P.D. Jones. 2013. A scPDSI-based global data set of dry and wet spells for 1901–2009. Journal of Geophysical Research – Atmospheres 118: 4025–4048 https://doi.org/10.1002/jgrd.50355.

Stephens, S.L., and P.Z. Fulé. 2005. Western pine forests with continuing frequent fire regimes: possible reference sites for management. Journal of Forestry 103: 357–362.

Stephens, S.L., C.N. Skinner, and S.J. Gill. 2003. Dendrochronology-based fire history of Jeffrey pine–mixed conifer forests in the Sierra San Pedro Martir, Mexico. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 33: 1090–1101 https://doi.org/10.1139/x03-031.

Swetnam TW, Baisan CH. 1996. Fire histories of montane forests in the Madrean borderlands. In: Ffolliott PF, DeBano LF, Baker MB, Gottfried GJ, Solis-Garza G, Edminster CB, Neary DG, Allen LS, Hamre RH (technical coordinators) Effects of fire on Madrean Province ecosystems: a symposium proceedings. USDA Forest Service General Technical Report RM-GTR-289, Rocky Mountain Range and Forest Experiment Station, Fort Collins. pp 15−36

Swetnam, T.W., C.H. Baisan, and J.M. Kaib. 2001. Forest fire histories of the sky islands of La Frontera, changing plant life of La Frontera. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

Swetnam, T.W., and J.L. Betancourt. 1998. Mesoscale disturbance and ecological response to decadal climatic variability in the American Southwest. Journal of Climate 11: 3128–3147 https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0442(1998)011%3C3128:MDAERT%3E2.0.CO;2.

Thoms, C.A., and D.R. Betters. 1998. The potential for ecosystem management in Mexico’s forest ejidos. Forest Ecology and Management 103: 149–157 https://doi.org/10.1016/s0378-1127(97)00184-9.

Turner, M.G., W.L. Baker, C.J. Peterson, and R.K. Peet. 1998. Factors influencing succession: lessons from large, infrequent natural disturbances. Ecosystems 1: 511–523 https://doi.org/10.1007/s100219900047.

Turner, M.G., R.H. Gardner, and R.V. O’Neill. 2001. Landscape disturbance dynamics. Chapter 7. In Landscape ecology in theory and practice: pattern and process, ed. M.G. Turner, R.H. Gardner, and R.V. O’Neill, 175–228. New York: Springer-Verlag.

VanDerWal J, Falconi L, Januchowski S, Shoo L, Storlie C. 2014. SDMTools: species distribution modelling tools: tools for processing data associated with species distribution modelling exercises. R package version 1.1-221. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=SDMTools. Accessed 30 May 2018.

Villarreal, M.L., L.M. Norman, K.G. Boykin, and C.S. Wallace. 2013. Biodiversity losses and conservation trade-offs: assessing future urban growth scenarios for a North American trade corridor. International Journal Biodiversity Science Ecosystem Services Management 9: 90–103 https://doi.org/10.1080/21513732.2013.770800.

Villarreal ML, Poitras TB. 2018. Mapped fire perimeters from the Sky Island Mountains of US and Mexico: 1985−2011. US Geological Survey data release. https://doi.org/10.5066/F76Q1WJ1. Accessed 30 May 2018.

Villarreal, M.L., and S.R. Yool. 2008. Analysis of fire-related vegetation patterns in the Huachuca Mountains, Arizona, USA, and Sierra los Ajos, Sonora, Mexico. Fire Ecology 4: 14–33 https://doi.org/10.4996/fireecology.0401014.

Wang, T., A. Hamann, D. Spittlehouse, and C. Carroll. 2016. Locally downscaled and spatially customizable climate data for historical and future periods for North America. PLoS One 11 (6): e0156720 https://adaptwest.databasin.org/pages/adaptwest-climatena. Accessed 30 May 2018.

Warshall P. 1995. The Madrean Sky Island Archipelago: a planetary overview. In: DeBano LH, Ffolliott PH, Ortega-Rubio A, Gottfried GJ, Hamre RH, Edminster CB (technical coordinators) Biodiversity and management of the Madrean Archipelago: the Sky Islands of southwestern United States and northwestern Mexico. USDA Forest Service General Technical Repot RM-GTR-264, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station, Fort Collins. pp 6–18

Waters, M.R., and J.C. Ravesloot. 2001. Landscape change and the cultural evolution of the Hohokam along the Middle Gila River and other river valleys in south-central Arizona. American Antiquity 66: 285–299 https://doi.org/10.2307/2694609.

White, J., K. Ryan, C. Key, and S. Running. 1996. Remote sensing of forest fire severity and vegetation recovery. International Journal of Wildland Fire 6: 125–136 https://doi.org/10.1071/wf9960125.

Whitman, E., E. Batllori, M.-A. Parisien, C. Miller, J.D. Coop, M.A. Krawchuk, G.W. Chong, and S.L. Haire. 2015. The climate space of fire regimes in north-western North America. Journal of Biogeography 42: 1736–1749 https://doi.org/10.1111/jbi.12533.

Whittaker, R.H., and W.A. Niering. 1965. Vegetation of the Santa Catalina Mountains, Arizona: a gradient analysis of the south slope. Ecology 46: 429–452 https://doi.org/10.2307/1934875.

Wickham, H. 2009. ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. New York: Springer-Verlag http://ggplot2.org/. Accessed 30 May 2018.

Wilder, M., G. Garfin, P. Ganster, H. Eakin, P. Romero-Lankao, F. Lara-Valencia, A.A. Cortez-Lara, S. Mumme, C. Neri, F. Muñoz-Arriola, and R.G. Varady. 2013. Climate change and US–Mexico border communities. In Assessment of climate change in the southwest United States. A report by the Southwest Climate Alliance, ed. G. Garfin, A. Jardine, R. Merideth, M. Black, and S. LeRoy, 340–384. Washington, D.C.: Island Press.

Williams, C.J., F.B. Pierson, P.R. Robichaud, and J. Boll. 2014. Hydrologic and erosion responses to wildfire along the rangeland–xeric forest continuum in the western US: a review and model of hydrologic vulnerability. International Journal of Wildland Fire 23: 155–172 https://doi.org/10.1071/wf12161.

Wimberly, M.C., M.A. Cochrane, A.D. Baer, and K. Pabst. 2009. Assessing fuel treatment effectiveness using satellite imagery and spatial statistics. Ecological Applications 19: 1377–1384 https://doi.org/10.1890/08-1685.1.

Yocom-Kent, L.L., P.Z. Fulé, P.M. Brown, J. Cerano-Paredes, E. Cornejo-Oviedo, C.C. Montaño, S.A. Drury, D.A. Falk, J. Meunier, H.M. Poulos, C.N. Skinner, S.L. Stephens, and J. Villanueva-Díaz. 2017. Climate drives fire synchrony but local factors control fire regime change in northern Mexico. Ecosphere 8: e01709 https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.1709.

Zozaya, E.L., L. Brotons, and S. Saura. 2011. Recent fire history and connectivity patterns determine bird species distribution dynamics in landscapes dominated by land abandonment. Landscape Ecology 27: 171–184 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-011-9695-y.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank J. Prickett for his early efforts developing a method for fire identification in Mexico as part of his Master’s thesis at the University of Arizona. We would also like to thank M. Coe and R. Petrakis of the University of Arizona for their efforts in processing Landsat data. We thank E. Margolis and S. Howard, who provided thoughtful reviews of an early draft of this manuscript. We appreciate the support of J. Smith, S. Benjamin, and M. Tongue of the US Geological Survey. Thanks for ongoing support from our home institutions and from the McGarigal Lab at the University of Massachusetts. Any use of trade, product, or firm names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the US government.

Funding

Funding was provided by the Land Change Science Program of the US Geological Survey.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is available in the ScienceBase-Catalog repository, https://doi.org/10.5066/F76Q1WJ1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MLV, SLH, JMI, and CCM conceived and designed the study. MLV developed the mapping approach and TBP contributed major effort in identification of fires, digitizing perimeters, image processing, and accuracy assessment. MLV and SLH analyzed and interpreted fire patterns and environmental data. All authors participated in writing the paper; JMI and CCM made significant contributions to writing the study area and fire history descriptions, as well as providing insightful discussion. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix