Abstract

Background

Expansion of juniper (Juniperus spp. L.) and pinyon (Pinus spp. L.) into sagebrush steppe habitats has been occurring for over a century across western United States. Vegetation and fuel treatments, with the goal of increasing landscape diversity and herbaceous productivity, and reducing woody fuels are commonly implemented to mitigate effects of woodland encroachment in sagebrush ecosystems. This study was conducted in conjunction with the Sagebrush Steppe Treatment Evaluation Project (SageSTEP) and was designed to determine the impact of vegetation treatments on fuel variables two years post treatment in sagebrush steppe with an expanding juniper or pinyon −juniper woodland component. Ten locations that characterize common sagebrush steppe sites with an expanding woodland component in the Intermountain West were chosen for analysis. These woodland sites, covering a gradient of juniper development phases, were treated with mechanical (cut and leave) and prescribed fire treatments.

Results

Two years post treatment, prescribed fire increased herbaceous biomass and reduced shrub biomass and down woody debris, but was not as effective in woodlands with higher juniper densities. Mechanical treatments increased herbaceous biomass and were effective in preserving the shrub biomass but increased down woody debris, which could lead to severe fire effects in the future.

Conclusions

We conclude that both prescribed fire and mechanical treatments are important management tools for maintenance and restoration of sagebrush steppe in areas that support juniper woodland expansion, but the differences in effects on shrub biomass and woody debris must be considered. A combination of the two treatments could lead to desirable effects in many areas.

Resumen

Antecedentes

La expansión de juníperos (Juniperus spp. L.) y pinos (Pinus spp. L.) en hábitats de la estepa graminosa de artemisia (sagebrush−grass steppe) ha venido ocurriendo desde hace más de cien años a través del oeste de los EEUU. Tratamientos de vegetación y combustibles, con el objetivo de incrementar la diversidad a nivel de paisaje y la productividad herbácea y reducir los combustibles leñosos, son comúnmente implementados para mitigar el efecto de la invasión de leñosas en este ecosistema. Este estudio fue conducido en conjunto con el Proyecto de Evaluación del Tratamiento de la Estepa de artemisia (SageSTEP) y fue diseñado para determinar el impacto de tratamientos de vegetación sobre variables de combustibles dos años post tratamiento en áreas de esta estepa que contenían un componente de expansión leñosa de junípero o de pino−junípero. Diez ubicaciones que caracterizan sitios de esta estepa de artemisia, con componentes de expansión de leñosas en el oeste inter-montano, fueron elegidas para su análisis. Estos sitios leñosos que cubrían un gradiente de fases de desarrollo de junípero, fueron tratados mecánicamente (corte y dejado en el lugar) y con quemas prescriptas.

Resultados

Dos años luego de los tratamientos, las quemas prescriptas incrementaron la biomasa herbácea y redujeron la biomasa de arbustos y de los residuos leñosos en el suelo, pero no fueron tan efectivas en bosques con mayores densidades de juníperos. Los tratamientos mecánicos incrementaron la biomasa herbácea y fueron efectivos en preservar la biomasa de arbustos, pero incrementaron los residuos leñosos en el suelo, los cuales pueden conducir a efectos severos del fuego en el futuro.

Conclusiones

Concluimos que tanto las quemas prescriptas como los tratamientos mecánicos son importantes herramientas de manejo para el mantenimiento y restauración en áreas que sustentan la expansión de bosques de juníperos, aunque las diferencias en sus efectos en la biomasa de arbustos y residuos leñosos en el suelo deben ser consideradas. Una combinación de los dos tratamientos puede conducir a obtener efectos deseables en muchas áreas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Sagebrush (Artemisia spp. L.) ecosystems in the western United States are contracting due to expansion of juniper (Juniperus spp. L.) and pinyon (Pinus spp. L.) −juniper woodland expansion at higher elevations, and invasion of annual grasses at lower elevations (Chambers et al. 2014). Juniper and pinyon −juniper woodlands and savannas are also native to the western United States, covering more than 30 million ha (West 1999). Hereafter, we will refer to these woodlands as simply juniper woodlands. Over the past 130 to 150 years, there has been an increase in tree density within its historical extent, and an encroachment of juniper woodlands into adjacent vegetation types (Miller et al. 2005, Miller et al. 2008), primarily into the sagebrush steppe in the Great Basin.

The encroachment process of juniper woodland into sagebrush steppe has been described in three phases (Miller et al. 2005, Miller et al. 2008). Phase 1 has an open, actively expanding juniper canopy cover of ≤0% with an intact shrub layer; Phase 2 has an actively expanding juniper cover between 10 and 30% and a thinning shrub layer; and Phase 3 has a nearly stabilized juniper cover > 30% with ≥75% shrub mortality. As woodland development progresses, the abundance and richness of sagebrush steppe vegetation decreases, creating large, sparsely vegetated interspaces (Bunting et al. 1999, Miller et al. 2013). As a consequence of loss in native herbaceous and shrub vegetation, many wildlife species associated with sagebrush steppe habitats have become conservation concerns (Wisdom et al. 2005). The expansion of juniper woodlands has also influenced the continuity and availability of wildland fuels (Miller et al. 2013, Young et al. 2015) and increased accumulation of litter and duff resulting from juniper leaf-fall (Weiner et al. 2016). A fuel bed characterized by sparse vegetation, down woody debris, litter, and duff significantly increases fire return interval, but when fires do occur, they tend to be more severe (Miller et al. 2013, Strand et al. 2013). For clarity, fuel is defined as the live and dead biomass that can contribute to the spread, intensity, and severity of a fire (Rothermel 1983). Fire behavior variables such as rate of spread, potential for crown fire, fire residence time, and fire severity are affected by changes in vegetation (Schoennagel et al. 2004, Strand et al. 2013, Weiner et al. 2016).

Land managers have long recognized the negative impacts of juniper woodland expansion on sagebrush steppe ecosystems, and conduct various treatments to counter their effects (Bates et al. 2011, Bates and Davies 2016). Common treatment strategies in woodlands include removing juniper by burning and cutting (Miller et al. 2005, Miller et al. 2014). Juniper removal treatments are often implemented across hundreds to thousands of hectares and lead to patches of different treatment effectiveness, altered vegetation structure and composition (Miller et al. 2014, Roundy et al. 2014, Bybee et al. 2016), and changed fuel bed characteristics (Young et al. 2015), all of which would directly affect fire behavior and fire effects of future wildfires.

The purpose of this study was to quantify the effect of mechanical (cut and leave) and prescribed fire vegetation treatments on the fuel beds in expanding juniper woodlands two years after implementation of treatments. Key fuel bed strata included herbaceous biomass, shrub biomass, and downed woody debris (DWD). In particular, we sought to determine if the treatments resulted in differences in those fuel bed strata. We expected all treatments to reduce shrub and tree abundance and consequently increase herbaceous biomass, at least in the short term. We also expected mechanical treatments to increase downed woody fuel abundance in proportion to the overstory shrub and tree mortality. We expected higher increases in herbaceous biomass and lower levels of DWD in treatments implemented in early phases of woodland development.

Methods

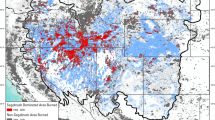

This study was conducted in conjunction with the Sagebrush Steppe Treatment Evaluation Project (SageSTEP; McIver et al. 2010). SageSTEP was designed to monitor long-term changes to the ecosystem as a result of different treatment methods in juniper woodland and sagebrush steppe communities of the Intermountain West, USA. The study included data from 10 sites (Fig. 1) located on big sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata Nutt.) ecological sites ranging in elevation from 1400 to 2500 m with mean annual precipitation ranging from 230 to 410 mm. Site information details can be found in McIver and Brunson (2014). The 10 sites impacted by the encroachment of juniper into sagebrush steppe were divided into three regions representing western juniper (J. occidentalis Hook.; 4 sites), Utah juniper (J. osteosperma [Torr.] Little; 4 sites), and a combination of Utah juniper and one-seed pinyon (Pinus monophylla Torr. & Frém.; 2 sites). At each site, three treatments were applied across 10 to 30 ha plots and included: 1) untreated control plots, 2) prescribed fire intended to blacken 100% of the plot, and 3) a mechanical treatment using a chainsaw to cut all juniper (and pinyon if present) taller than 0.5 m and leaving the trees where they fell. Fire treatments were hand-ignited broadcast burns conducted between August and October 2006 or 2007. The tree canopy was reduced to less than 5% across all burns. Mechanical treatments were conducted September through November the same years as the prescribed fire treatments. Juniper and pinyon trees were cut with chainsaws and left on the site. See Miller et al. (2014) and Roundy et al. (2014) for further details about treatments. No seeding was done post treatment and the sites were excluded from livestock grazing.

Sites were sampled two years post treatment. Standard measurement protocols were used across all sites (Bourne and Bunting 2011, McIver and Brunson 2014). Each of the 10 sites used a randomized design to create treatment areas that were varying in size at each site and ranged from 20 to 80 ha, with 14 to 24 permanent 0.1 ha (30 m × 33 m) sampling plots established within each treatment. Each plot was established along a systematic grid with a minimum distance of 50 m between plots. Within plots, seven permanent transects running parallel to the 33 m length were established. Five transects were used to determine species composition utilizing the line-point intercept method (Bonham 1989). The planar intercept method was used to sample all dead woody fuels (Brown et al. 1982). Herbaceous fuel loads were determined by destructive sampling (Bonham 1989) within 0.25 m2 quadrats placed every other meter along the remaining two transects. Shrub composition was estimated by allometric methods specific to big sagebrush utilizing individual plants destructively sampled outside the plots (Tausch 1989). Total shrub biomass was divided into two categories: 1-h (twigs 0 to 0.63 cm in diameter) and 10-h (branches 0.63 to 2.54 cm) (Frandsen 1983). Downed woody debris (DWD) was categorized into standard size classes related to rate of fuel moisture change: 10-h DWD is small branches (0.63 to 2.54 cm diameter), 100-h DWD is medium branches (2.54 to 7.62 cm diameter), and 1000-h DWD is large branches and tree trunks (> 7.62 cm diameter). Fuel variables analyzed included live herbaceous, total shrub biomass, 10-h DWD, 100-h DWD, 1000-h solid DWD, and 1000-h rotten DWD. All fuel variables were summarized and analyzed at the site and plot levels. The plots at each site were divided into groups based on the woodland development phase as described by Miller et al. (2005), since we expected that the plot vegetation composition prior to treatment would influence post-treatment response.

Relative change in fuel load was computed for each fuel variable by subtracting the post-treatment value (two years post) from the pre-treatment value and dividing by the pre-treatment value. Relative change was also computed for each fuel type and treatment within woodland development phases.

Statistical software Systat 13.1 (Systat 2009) was used for all statistical analyses. At the site level, relative change was compared between the two treatment types (prescribed fire and mechanical) using a paired student’s t-test for live herbaceous, total shrub, and 10-h DWD fuels. Treatment differences were also compared for the same fuel types within woodland development phase with a paired student’s t-test. At the plot level, we used analysis of variance (ANOVA) to determine the effect of treatment (control, prescribed fire, mechanical) on fuel loads for herbaceous biomass, shrub biomass, and downed woody debris two years post treatment within each of the three woodland regions. Pre-treatment fuel loads were included as co-variates in the model to account for differences in vegetation and fuel composition at the plot level. Tukey’s post-hoc test was applied to test for significance between individual treatments at the P = 0.05 level. The three juniper woodland types were analyzed separately. For each woodland region, fuel types within woodland development phase were analyzed separately, resulting in 9 to 28 samples in each analysis (n is reported with the results in Tables 1, 2 and 3). Following analysis, we reviewed the residual of the fitted value to confirm normality in the data.

Results

Site level analysis

Differences in fuel loading responses at the site level were found between prescribed fire and mechanical treatment (Fig. 2) two years after the treatments. Both prescribed fire and mechanical treatments increased the live herbaceous biomass; however, at the site level, the difference between the two treatment types was not significant. Prescribed fire reduced shrub biomass while the mechanical treatment did not. Downed woody debris (10-h) increased following mechanical treatments but was largely unaffected by the prescribed burn. Treatment resulted in an increase in herbaceous biomass in all woodland development phases; however, no significant difference was observed between fire and mechanical treatments (Fig. 3). Total shrub biomass was significantly lower in prescribed fire compared to mechanical treatment in Phases 1 and 2 of woodland development but not in Phase 3 (Fig. 3). Downed woody debris (10-h) was higher following mechanical compared to prescribed fire treatment in Phases 2 and 3, but not in Phase 1 (Fig. 3).

Relative change in the sagebrush −woodland sites for live herbaceous, total shrub and 10-h DWD fuels two years post treatment for prescribed fire and mechanical treatments. Values are means and error bars are standard deviations of percent change for the 10 sites. Treatment effect (P) comparing prescribed fire and mechanical treatment is reported for each fuel type

Relative changes in live herbaceous, total shrub, and 10-h DWD fuels two years post treatment displayed by woodland development phase: Phase 1 (P1), Phase 2 (P2), and Phase3 (P3). Values are means and standard deviations of percent change at the 10 sites. Treatment effect (P) comparing prescribed fire and mechanical treatment is reported for each fuel type and woodland development phase

Young juniper woodlands did not have an abundance of 100-h and 1000-h DWD, and the observations of 1000-h DWD fuel were not normally distributed and were therefore excluded from further statistical analysis. Changes in large down woody debris was highly variable, but generally increased following treatment, particularly in more developed woodlands.

Prescribed fire

Results from analysis of variance at the plot level are summarized for the three woodland regions in Tables 1, 2 and 3. Prescribed fire resulted in a three-fold to four-fold increase in live herbaceous biomass in Phases 1 and 2 across regions, and even larger increases in Phase 3 (Tables 1, 2 and 3). Although the percent increase in herbaceous biomass was higher in Phase 3, it should be noted that the pre-treatment amount of biomass was less than half in Phase 3 compared to Phases 1 and 2 across regions (Tables 1, 2 and 3). Thus, the absolute amount of biomass increased more in Phases 1 and 2, compared to Phase 3. For example, in the western juniper region, biomass increased from 257 to 820 kg ha−1 in Phase 1, from 207 to 797 kg ha−1 in Phase 2, and from 130 to 541 kg ha−1 in Phase 3 (Table 1). Similar results were observed for pinyon −juniper and Utah juniper regions, although the productivity in those regions were lower (Tables 2 and 3).

Prescribed fire reduced shrub biomass by more than 90% in Phase 1 and Phase 2 in the western juniper and Utah juniper woodland types (Tables 1 and 3), while the reduction was around 40 to 80% in pinyon −juniper woodlands. No effect of prescribed fire treatment was detected for shrub biomass in Phase 3 in any of the woodland regions (Tables 1, 2 and 3). Note that pre-treatment shrub biomass decreased along the woodland development gradient and was 3-fold to 30-fold greater in Phase 1 compared to Phase 3 prior to treatment.

Downed woody debris of the 10-h size class generally decreased in Phase 1 and Phase 2 but increased in Phase 3 following fire (Fig. 3), but results were variable across regions (Tables 1, 2 and 3). Prescribed fire resulted in a decrease in 10-h DWD by 59% in Phase 1 and 38% in Phase 2 in the western juniper region (Table 1), and increased by 81% in Phase 3 in the Utah juniper region (Table 3). Effects on 100-h DWD were highly variable across regions. Although the results were not significant at the P = 0.05 level, 100-h DWD generally decreased in Phase 1 and increased in Phase 3 as a result of prescribed fire treatment (Tables 1, 2 and 3).

Mechanical treatment

Mechanical treatments resulted in an increase in live herbaceous biomass in Phases 2 and 3 in the western juniper (Table 1) and Utah juniper (Table 3) regions, but not in the pinyon −juniper region (Table 2). Total shrub biomass was generally not affected by the mechanical treatment except for a 38% decrease in Phase 1 of the western juniper region.

Mechanical treatments resulted in an increase in DWD in older woodland development phases across regions. Changes in 10-h DWD were not detectable in Phase 1 in the western juniper and Utah juniper regions (Tables 1 and 3), while 10-h DWD increased in Phase 2 by 36 to 141% across regions. In Phase 3, 10-h DWD approximately doubled in the western juniper and pinyon −juniper region and increased fourfold in the Utah juniper region. Mechanical treatment resulted in increased 100-h DWD across all regions and phases. In Phase 1, 100-h DWD increased by a factor of 1.5, while the increase was two-fold to four-fold in Phase 2 and four-fold to five-fold in Phase 3. The mechanical treatment converted fuels from the live tree canopy strata to the DWD strata. Thus, there is a logical progression of treatment influence from the minimal DWD increase recorded on Phase 1 to a more pronounced impact in Phase 2 and Phase 3 with their higher abundance and size of juniper on the sites pre treatment.

Discussion

The expansion of juniper woodlands has altered the vegetation composition across the Intermountain West (Bunting et al. 1999, Miller et al. 2005, Miller et al. 2008). The transition from sagebrush steppe to woodland reduces forage quantity and quality for wildlife and domestic animals (Wisdom et al. 2000), negatively impacts wildlife habitat for sagebrush obligate species such as the greater sage-grouse (Centrocercus urophasianus [Bonaparte, 1827]; Baruch-Mordo et al. 2013), disrupts nutrient cycling, increases erosion, and changes the fire frequency of the system (Blackburn and Tueller 1970, Miller and Tausch 2001, Bates et al. 2007). To mitigate problems associated with this encroachment, land managers have utilized a wide range of strategies on the landscape, among which are prescribed fire and mechanical treatments. These treatments change the fuel structure of these landscapes, influencing the abundance and continuity of herbaceous biomass, shrub biomass, and downed woody debris, leading to altered expectations for fire behavior and effects associated with a potential future wildfire.

Prescribed fire

The response to prescribed fire was similar across the three juniper woodland regions. Prescribed fire resulted in an increase in live herbaceous biomass in Phases 1, 2, and 3 in western juniper, pinyon −juniper, and Utah juniper sites. An increase in live herbaceous biomass is expected post fire. The removal of competition from shrubs and trees combined with the rapid release of nutrients into the system facilitates regeneration and growth (Everett and Ward 1984, Agee 1993, Rau et al. 2008, Miller et al. 2014). An increase in herbaceous biomass is expected to continue until available space and resources are expended (Tausch and Tueller 1977, Everett and Ward 1984, Bates et al. 2005).

Prescribed fire decreased shrub biomass by about 90% in Phase 1 and Phase 2 woodlands; however, the reduction of shrub biomass in Phase 3 was variable. This variability was unexpected. Big sagebrush is particularly sensitive to fire and experiences stand replacement when consumed (Wambolt and Payne 1986, Bunting et al. 1987). Sagebrush biomass is expected to increase given time, but the recruitment process is slow and it may take 35 to 100 years to fully recover to pre-fire conditions (Pieper and Wittie 1990, Wambolt et al. 2001). The prescribed fire treatment was designed for 100% of the plots to be blackened; thus, a surviving shrub component indicates an incomplete prescribed fire. This is most likely due to the limited availability of fine fuels to support the flaming front in a Phase 3 woodland.

Downed woody debris had the highest variability in consumption of any fuel variable measured. Generally across sites, DWD decreased in Phases 1 and 2, with the largest reduction in Phase 1. In Phase 3, we generally observed an increase in DWD, particularly in the larger size class (100-h fuels), but the variability was high across sites. This variability was probably due to continuity of fine fuels and their ability to carry fire, and also to the wide variety of fuel moisture and weather conditions for which these treatments were implemented across the woodland sites.

Fuel consumption decreased along the successional gradient from young to older woodlands. Phases 1 and 2 had the highest herbaceous fuel load, which more likely resulted in a continuous flaming front, as was reflected in the greater shrub biomass consumption. Thus, when DWD was consumed, it occurred in those phases. Phase 3 was known for a lack of fuel continuity, making it difficult to burn (Blackburn and Tueller 1970, Pieper and Wittie 1990, Miller and Tausch 2001). Fire treatments are therefore often not recommended for Phase 3 (Bates et al. 2000, Miller et al. 2005) because it requires more extreme fire conditions that are conducive to a crown fire (Huffman et al. 2009), which is generally not desired.

The total fuel load on site decreased in Phases 1 and 2 after prescribed fire treatment. Although there was a sizable increase in the herbaceous biomass, it had not yet compensated for the amount of sagebrush biomass consumed two years post treatment. This difference will likely decrease in the future as herbaceous biomass continues to increase into the open spaces and as shrubs recover from the treatment (Tausch and Tueller 1977, Everett and Ward 1984, Bates et al. 2005). Fire severity in these two phases is also expected to decrease, with the exception of that part of Phase 2 that experienced an increase in 1000-h DWD solid fuel. In Phase 3, pinyon −juniper had a herbaceous biomass increase greater than the amount of shrub biomass consumed. This suggests that there is an increase in fuel and fuel continuity across the system, increasing the probability of fire ignition and spread.

Because the young juniper woodlands did not have an abundance of 1000-h DWD and exhibited high variability, the observations of these fuel categories were not normally distributed and were therefore excluded from statistical analysis. These fuels were estimated along five 30 m transects, (i.e., 150 m total transect length per plot) since larger fuels have been shown to vary at broader scales than the fine fuels (Keane et al. 2012). For future studies, we recommend longer transects or a different sampling methodology for the 1000-h fuel categories for fuels assessments in sagebrush steppe and juniper woodlands.

Mechanical treatment

Herbaceous biomass response varied by successional phase following mechanical treatment. Mechanical treatments did not significantly increase herbaceous biomass in Phase 1, but increased two-fold to three-fold in Phase 2, and three-fold to six-fold in Phase 3 in western juniper (Table 1) and Utah (Table 3) juniper. Herbaceous biomass in Phase 1 woodland would be expected to be the least effected by juniper woodland encroachment, thus it was not surprising that treatment results were not significant. However, an increase in herbaceous biomass in Phase 2 was found in two of the woodland regions, supporting the notion that, even at lower juniper densities, removal of juniper releases enough resources for a herbaceous vegetation response to be measurable (Bates et al. 2005, Miller et al. 2005). Other studies were primarily conducted in Phase 2 and Phase 3 juniper woodlands and found that mechanical treatments increased soil nitrogen and water availability, leading to an initial flush of herbaceous biomass in the first two years post treatment (Tausch and Tueller 1977; Bates et al. 1998, 2000, 2005). Generally, herbaceous biomass peaked within the first five to ten years, and shrubs eventually increased in abundance (Tausch and Tueller 1977, Skousen et al. 1989, Bates et al. 2005, Miller et al. 2014). Increased herbaceous fuel connectivity may lead to increased probability for a fire to carry across the landscape.

Shrub biomass was generally not affected by mechanical treatment. It was expected that shrub biomass would increase as sagebrush would have benefited from the increase in soil nitrogen and water availability. Previous studies showed that chaining treatments (a type of mechanical treatment that has been used for brush control) caused a vigorous shrub response within the first two years post treatment (Tausch and Tueller 1977, Skousen et al. 1989). However, Bates et al. (2005) found minimal shrub response 13 years after a mechanical treatment. He cited a lower initial shrub density within his plots as a possible cause of this slower response. This would not be accurate in our study as Phase 2 still had a relatively intact shrub component. Continued long-term study is needed to determine if the shrub layer will respond to the cut-and-leave mechanical treatment.

Changes in DWD varied by successional phase. In Phase 1, we did not observe any increase in 10-h DWD fuels in two of the regions, but a significant increase was recorded in the pinyon −juniper region (Table 2). On Utah juniper and pinyon −juniper sites in Phase 1, we observed an increase in 100-h DWD. The increase in larger fuels indicates that conversion of ≤10% juniper tree cover to surface fuel may be defined by tree trunks and has a minimal influence on the smaller fuels in the fuel bed. Mechanical treatment influences on DWD in Phase 2 and Phase 3 were more pronounced (Tables 1, 2 and 3). The fuel increase was expected and is a function of converting live tree biomass to downed woody debris, demonstrating that juniper canopy cover will remain in the fuel bed two years post treatment.

Mechanical treatments used chainsaws to remove all trees taller than 0.5 m, clearly reducing the probability of a future crown fire. While the potential of a canopy fire has been dramatically reduced by the mechanical treatment, there is a corresponding increase to DWD surface fuels, which can increase the potential for a high-severity surface fire. In these surface DWD fuels, fire-season moisture content is less than in live trees and the fuel is now layered on the surface, which can increase soil heating in the event of a fire, leading to increased mortality of herbaceous vegetation and opening up the landscape for invasion by exotic annual grasses.

The heavier woody fuels (100-h DWD) added to the fuel bed were substantial in our study. For example, pinyon −juniper pre treatment had 1620 kg ha−1 100-h DWD, but post treatment it had over 7200 kg ha−1 100-h DWD. The 100-h DWD and 1000-h fuels can remain in the ecosystem for decades. Decay rates in the sagebrush steppe are variable and slow (Harmon et al. 1986) and may be influenced more through abiotic factors than biotic factors (Waichler et al. 2001). As the 1000-h fuels decompose and become rotten, they have an increased risk of smoldering and soil heating when burned (Passovoy and Fulé 2006), which may increase fire’s effects on soil and vegetation.

Study-wide trends

We focus on three fuel components, including live herbaceous, total shrub, and 10-h DWD, due to their importance in influencing fire intensity and spread as well as fire effects (Rothermel 1983, Ottmar et al. 2007). Both prescribed fire and mechanical treatments increased live herbaceous biomass on juniper woodland sites (Fig. 2). The percent increase was greater for fire treatment compared to mechanical treatment. Mechanical treatments understandably increase 10-h DWD the greatest, given that trees were cut and left on the sites. This increase was greatest where woody plant cover was highest —in the Phase 3 woodland. The greater the pre-treatment pinyon and juniper cover, the greater the increase in 10-h DWD post-treatment.

The response of live herbaceous biomass was most variable for Phase 3 woodlands as compared to Phases 1 and 2 (Fig. 3; Tables 1, 2 and 3). Percent increases in live herbaceous biomass were greatest for Phase 3 woodlands for both fire and mechanical treatments, but those sites had low herbaceous biomass prior to treatment (Tables 1, 2 and 3); thus, small absolute increases resulted in large relative increases. Small residual amounts of herbaceous plant populations resulted in erratic responses of those species.

Conclusions

Prescribed burning and mechanical treatments altered fuels, and significant effects were documented two years after implementation across woodland types. Changes in vegetation amounts and structure will likely alter potential fire behavior of the ecosystem in the future. Herbaceous biomass increases resulting from these treatments could increase the likelihood of fire spread if they become ignited. The mechanical treatment effectively reduced live tree biomass at all sites, but converted it to DWD, which may have increased fuel continuity. The greatest increases in DWD were observed on the Phase 3 woodland sites. As the ecosystem recovers from treatment, DWD will persist in the surface fuels, which could increase fire severity.

Prescribed fire’s effects were similar within each phase across the woodland regions. The increased post-treatment herbaceous biomass may assist in perpetuating fire spread, making fire effects more consistent. An important difference between the treatments was the highly variable nature of prescribed fire compared to mechanical treatment. Only the fire treatment resulted in significant increases in herbaceous biomass in Phase 1, while both fire and mechanical treatments resulted in increased herbaceous biomass in Phases 2 and 3, suggesting that prescribed fire is the most effective treatment in Phase 1, while fire and mechanical treatments result in similar effects on herbaceous biomass in more developed woodlands. Mechanical treatment had a very uniform effect. Shrub biomass was largely lost in the prescribed fire treatment while it remained unaffected in the mechanical treatments. The potential for crown fire was reduced while there was a corresponding increase in all size classes for DWD surface fuels in Phase 2 and Phase 3. The increase in fuel load may affect the ecosystem for many years due to the arid environmental conditions. The increase in DWD fuel will persist and add to the potential fire severity in future fires, potentially leading to greater soil heating and herbaceous biomass mortality. Thus, mechanical treatment of woodlands may best be used as a restoration strategy as opposed to a fuel mitigation strategy. Mechanical treatments may also be effectively used as an initial treatment prior to a prescribed fire treatments. Of the vegetation treatments studied, only prescribed fire reduced fuel in the ecosystem through the combustion of the shrub and DWD fuel strata. In Phase 3 woodlands, prescribed fire increased the surface fuel load by killing trees and resulting in greater tree fall.

In the future, it is expected that herbaceous biomass will continue to increase on the sites as grass species, in particular, respond to the release from competition from shrubs and trees. Sagebrush will re-establish on the burned sites and contribute to future fuel loading, but it will likely require more than a decade to achieve pre-treatment levels. Large-sized classes of DWD that were created by the treatments will remain on the sites for many decades as decomposition rates occur slowly in cold arid environments.

If management goals for vegetation treatments are to reduce fuel loads, then mechanical and some prescribed fire treatments may not be successful. For these vegetation treatments to be effective as fuel reduction treatments, it may be necessary to add a second treatment, such as mechanical followed by prescribed burning some years later.

Abbreviations

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of variance

- DWD:

-

Downed woody debris

- P1, P2, P3:

-

Phases 1, 2, and 3 of juniper woodland development

- SageSTEP:

-

Sagebrush Steppe Treatment Evaluation Project

References

Agee JK (1993) Fire ecology and Pacific northwest. Island Press, Washington, D.C.

Baruch-Mordo S, Evans JS, Severson JP, Naugle DE, Maestas JD, Kiesaecker JM, Falkowski MJ, Hagan CA, Reese KP (2013) Saving sage-grouse from the trees: a proactive solution to reducing a key threat to a candidate species. Biol Conserv 167:233–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2013.08.017

Bates JD, Davies KW (2016) Seasonal burning of juniper woodlands and spatial recovery of herbaceous vegetation. For Ecol Manag 361:117–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2015.10.045

Bates JD, Davies KW, Sharp RN (2011) Shrub-steppe early succession following invasive juniper cutting and prescribed fire. Environ Manag 47:468–481. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-011-9629-0

Bates JD, Miller RF, Svejcar TJ (1998) Understory patterns in cut western juniper (Juniperus occidentalis subsp. occidentalis hook.) woodlands. Great Basin Naturalist 58:363–374

Bates JD, Miller RF, Svejcar TJ (2000) Understory dynamics in cut and uncut western juniper woodlands. J Range Manag 53:119–126. https://doi.org/10.2307/4003402

Bates JD, Miller RF, Svejcar TJ (2005) Long-term successional trends following western juniper cutting. Rangel Ecol Manag 58:533–541.

Bates JD, Svejcar TS, Miller RF (2007) Litter decomposition in cut and uncut western juniper woodlands. J Arid Environ 70:222–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaridenv.2006.12.015

Blackburn WH, Tueller PT (1970) Pinyon and juniper invasion in black sagebrush communities in east-Central Nevada. Ecology 51:841–848. https://doi.org/10.2307/1933976

Bonham CD (1989) Measurements for terrestrial vegetation. John Wiley and Sons, New York

Bourne A, Bunting SC (2011) Guide for quantifying post-treatment fuels in the sagebrush steppe and juniper woodlands of the Great Basin. US Department of the Interior Technical Note 437, Bureau of Land Management, Denver

Brown JK, Oberheu RD, Johnston CM (1982) Handbook for inventorying surface fuels and biomass in the interior west. USDA Forest Service General Technical Report INT-129, Intermountain Forest and Range Experimental Station, Ogden

Bunting SC, Kilgore BM, Bushey CL (1987) Guidelines for prescribed burning in sagebrush-grass rangelands in the northern Great Basin. USDA Forest Service General Technical Report INT-231, Intermountain Research Station, Ogden

Bunting SC, Kingry JL, Strand EK (1999) Effects of succession on species richness of western juniper woodland/sagebrush steppe mosaic. In: Monsen SB, Richard S (eds) Proceedings: ecology and management of pinyon-juniper communities within the interior west. USDA Forest Service Proceedings RMRS-P-9, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Ogden, pp 76–81

Bybee J, Roundy BA, Young KR, Hulet A, Roundy DB, Crook L, Aanderud Z, Eggett DL, Cline NL (2016) Vegetation response to piñon and juniper tree shredding. Rangel Ecol Manag 69:224–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rama.2016.01.007

Chambers JC, Miller RF, Board DI, Pyke DA, Roundy BA, Grace JB, Schupp EW, Tausch RJ (2014) Resilience and resistance of sagebrush ecosystems: implications for state and transition models and management treatments. Rangel Ecol Manag 67:440–454. https://doi.org/10.2111/REM-D-13-00074.1

Everett RL, Ward K (1984) Early plant succession on pinyon-juniper controlled burns. Northwest Sci 58:57–68

Frandsen WH (1983) Modeling big sagebrush as a fuel. J Range Manag 36:596–600. https://doi.org/10.2307/3898349

Harmon ME, Franklin JR, Swanson FJ, Lattin JD, Gregory SV, Anderson NH, Cline SP, Aumen NG, Sedell JR, Lienkaemper GW, Cromack K Jr, Cummins KW (1986) Ecology of coarse woody debris in temperate ecosystems. Adv Ecol 15:133–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2504(08)60121-X

Huffman DW, Fulé PZ, Crouse JE, Pearson KM (2009) A comparison of fire hazard mitigation alternatives in pinyon-juniper woodlands of Arizona. For Ecol Manag 257:628–635. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2008.09.041

Keane RE, Gray K, Bacciu V, Leirfallom S (2012) Spatial scaling of wildland fuels for six forest and rangeland ecosystems of the northern Rocky Mountains, USA. Landsc Ecol 27:1213–1234. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-012-9773-9

McIver J, Brunson M, Bunting SC, Chambers J, Devo N, Doescher P, Grace J, Johnson D, Knick S, Miller R, Pellant M, Pierson F, Pyke D, Rollins K, Roundy B, Schupp E, Tausch R, Turner D (2010) The sagebrush steppe treatment evaluation project (SageSTEP): a test of state-and-transition theory. USDA Forest Service General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-237, Fort Collins

McIver JM, Brunson MW (2014) Multidisciplinary, multisite evaluation of alternative sagebrush steppe restoration treatments: the SageSTEP project. Rangel Ecol Manag 67:435–439. https://doi.org/10.2111/REM-D-14-00085.1

Miller RF, Bates JD, Svejcar TJ, Pierson FB, Eddleman LE (2005) Biology, ecology, and management of western juniper (Juniperus occidentalis). Agricultural Experiment Station Technical Bulletin 152, Oregon State University, Corvallis

Miller RF, Chambers JC, Pyke DA, Pierson FB, Williams JC (2013) Fire effects on vegetation and soils in the Great Basin region and the role of site characteristics. USDA Forest Service General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-308, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fort Collins

Miller RF, Ratchford J, Roundy BA, Tausch RJ, Pereia C, Hulet A, Chambers JC (2014) Response of conifer encroached shrublands in the Great Basin to prescribed fire and mechanical treatments. Rangel Ecol Manag 67:468–481. https://doi.org/10.2111/REM-D-13-00003.1

Miller RF, Tausch RJ (2001) The role of fire in pinyon and juniper woodlands: a descriptive analysis. In: Galley KEM, Wilson TP (eds) Proceedings of the invasive species workshop: the role of fire in the control and spread of invasive species. Tall Timbers Research Station Miscellaneous Publication 11, Tallahassee, pp 15–30

Miller RF, Tausch RJ, McArthur ED, Johnson DD, Sanderson SC (2008) Age structure and expansion of piñon –juniper woodlands: a regional perspective in the intermountain west. USDA Forest Service Research Paper RMRS-RP-69, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fort Collins

Ottmar RD, Sandberg DV, Riccardi CL, Prichard SJ (2007) An overview of the fuel characteristic classification system —quantifying, classifying, and creating fuelbeds for resource planning. Can J For Res 37:2383–2393. https://doi.org/10.1139/X07-077

Passovoy MD, Fulé PZ (2006) Snag and woody debris dynamics following severe wildfires in northern Arizona ponderosa pine forests. For Ecol Manag 223:237–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2005.11.016

Pieper RD, Wittie RD (1990) Fire effects in southwestern chaparral and pinyon –juniper vegetation. In: Krammes JS (ed) Effect of fire management of southwestern natural resources. USDA Forest Service General Technical Report RM-GTR-191, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experimental Station, Fort Collins, pp 87–93

Rau BM, Chambers JC, Blank RR, Johnson DW (2008) Prescribed fire, soil, and plants: burn effects and interactions in the central Great Basin. Rangel Ecol Manag 61:169–181. https://doi.org/10.2111/07-037.1

Rothermel RC (1983) How to predict the spread and intensity of forest and range fires. USDA Forest Service General Technical Report INT-143, Intermountain Forest and Range Experimental Station, Ogden

Roundy BA, Miller RF, Tausch RJ, Young K, Hulet A, Rau B, Jessop B, Chambers JC, Egget D (2014) Understory cover responses to piñon–juniper treatments across tree dominance gradients in the Great Basin. Rangel Ecol Manag 67:482–494. https://doi.org/10.2111/REM-D-13-00018.1

Schoennagel T, Veblen TT, Romme WH (2004) The interaction of fire, fuels, and climate across Rocky Mountain forests. BioScience 54:661–676. https://www.colorado.edu/geography/biogeography/publications/Schoennagel_et_al_2004.pdf

Skousen JG, Davis JN, Brotherson JD (1989) Pinyon –juniper chaining and seeding for big game in Central Utah. J Range Manag 42:98–104. https://doi.org/10.2307/3899303

Strand EK, Bunting SC, Keefe R (2013) Influence of wildland fire along a successional gradient in sagebrush steppe and western juniper woodlands. Rangel Ecol Manag 66:667–679. https://doi.org/10.2111/REM-D-13-00051.1

Systat (2009) Systat statistical analysis software version 13.1. For windows. Systat Software Inc., San Jose

Tausch RJ (1989) Comparison of regression methods for biomass estimation of sagebrush and bunchgrass. Great Basin Naturalist 49:373–380

Tausch RJ, Tueller PT (1977) Plant succession following chaining of pinyon –juniper woodlands in eastern Nevada. J Range Manag 30:44–49. https://doi.org/10.2307/3897334

Waichler WS, Miller RF, Doescher PS (2001) Community characteristics of old-growth western juniper woodlands. J Range Manag 54:518–527. https://doi.org/10.2307/4003580

Wambolt CL, Payne GF (1986) An 18-year comparison of control methods for Wyoming big sagebrush in southwestern Montana. J Range Manag 39:314–319. https://doi.org/10.2307/3899770

Wambolt CL, Walhof KS, Frisina MR (2001) Recovery of big sagebrush communities after burning in South-Western Montana. J Environ Manag 61:243–252. https://doi.org/10.1006/jema.2000.0411

Weiner NI, Strand EK, Bunting SC, Smith AMS (2016) Duff distribution influences fire severity in post-fire vegetation recovery in sagebrush steppe. Ecosystems 19:1196–1209. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-016-9994-x

West NE (1999) Juniper –pinyon savannas and woodlands of western North America. In: Anderson RC, Fralish JS, Baskin JM (eds) Savannas, barrens, and rock outcrop plant communities of North America. Cambridge University Press, London, pp 288–203

Wisdom MJ, Holthausen RS, Wales BC, Hargis CD, Saab VA, Lee DC, Hann WJ, Rich TD, Rowland MM, Murphy WJ, Eames MR (2000) Source habitats for terrestrial vertebrates of focus in the interior Columbia Basin: broad-scale trends and management implications. Volume 1—overview. USDA Forest Service General Technical Report PNW-GTR-485, Pacific Northwest Research Station, Portland

Wisdom MJ, Rowland MM, Suring LH (eds) (2005) Habitat threats in the sagebrush ecosystem: methods of regional assessment and applications in the Great Basin. Alliance Communications Group, Allen Press, Lawrence

Young KR, Roundy BA, Bunting SC, Eggett DL (2015) Utah juniper and two-needle pinon reduction alters fuel loads. Int J Wildland Fire 24:236–248

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the SageSTEP Program; Joint Fire Sciences Program; the College of Natural Resources; and the Department of Forest, Rangeland, and Fire Sciences. This is Contribution Number 90 of the Sagebrush Steppe Treatment Evaluation Project (SageSTEP), funded by the US Joint Fire Science Program, the Bureau of Land Management, and the National Interagency Fire Center. Special thanks to A. Smith, P. Morgan, J. McIver, and F. Rego for their assistance and suggestions on earlier drafts of this manuscript. Thanks to the statistician C. Williams for ideas and thoughts on the proper statistical analyses to explore. Thanks to A. Bourne, who remained available for consultation years after she graduated. And thanks to all the land management agencies’ personnel, colleagues, and SageSTEP crews who tirelessly collected the data year after year.

Funding

Funding was provided by the Joint Fire Science Program (05-S-08) SageSTEP project, the Bureau of Land Management, and the National Interagency Fire Center.

Availability of data and materials

Please contact author for data requests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CRB analyzed data and drafted the first version of the manuscript. All authors participated in the study conception and design, development of analysis methods, critical review, and final revision of the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Bernau, C.R., Strand, E.K. & Bunting, S.C. Fuel bed response to vegetation treatments in juniper-invaded sagebrush steppe. fire ecol 14, 1 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42408-018-0002-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s42408-018-0002-z