Abstract

Background

One of the important by-products is sesame seed meal; it is a by-product of sesame seed pressing. Sesame oil cake or meal is a relatively good source of crude protein which can replace part of basic ingredients in diets such as soybean.

Method

Fifteen growing male Barki lambs aged 5–6 months (18.50 ± 0.98 kg) were used to investigate the influence of replacing soybean meal (SBM) that incorporated (16% of control ration) sesame meal (SM) at 50% or 100% on feed and water intakes, nutrient digestibility, growth performance, rumen parameters, and economic evaluation. Lambs received one of the three tested complete feed mixtures that contained 16% SBM (R1), replaced 50% of SBM with SM (R2), contained (8% SBM + 8% SM) or completely replaced 100% of SBM with SM (R3) and contained 16% SM.

Results

Dietary treatments had no significant effect on all nutrient digestibility and total digestible nutrients value, meanwhile it decreased (P < 0.05) their contents of digestable crud protine when SBM was completely replaced by SM. Average daily gain (ADG) increased (P < 0.05) while increasing the level of replacement SBM by SM. Feed conversion expressed as g. gain improved (P < 0.05) with the increasing level of inclusion SM in the rations. Ruminal pH values increased (P < 0.05), meanwhile, values of NH3-N concentration insignificantly decreased; however, values of total volatile fatty acid concentration insignificantly increased when SBM was replaced at half or completely by SM. Economical efficiency improved by 147.9% and 163.5% for R2 and R3 compared to control (R1).

Conclusion

It can be mentioned that SM is a good source of protein and can be successfully used as an unconventional source in growing lamb rations without causing any deleterious effect on their performance, digestibility, and ruminal fermentation while realizing a decrease in feed cost with improving economic efficiency, so it can incorporate SM in sheep rations to improve profitability or net revenue and decrease feed cost/kg gain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The feedstuff market is suffering from price fluctuations and quite often availability problems (Stillman et al. 2009; Lawrence et al. 2010; Nikolakakis et al. 2014). These detrimental situations are usually observed for high-protein feed such as soybean meal (Indexmundi 2016a), but they can also be observed for cereals such as maize (Indexmundi 2016b), barley (Indexmundi 2016c), and other feed ingredients. Consequently, farmers have problems with supplying their livestock with good quality feed, while keeping the feed cost at manageable levels. Accordingly, nowadays there is an observed increasing demand for novel feedstuffs characterized by low price and decent availability, which can be utilized in livestock feed, without any adverse effect on animal health and productivity. Therefore, many by-products of the food and feed industries are now being examined as alternative feedstuffs (Bonos et al. 2017).

According to data for FAO (2014), sesame seed production occupied 78 million acres, with a production of 3.84 million tons. The sesame seeds contain on average 44–58% oil, 18–25% crude protein, 13.5% carbohydrates, and 5% ash (Yoshida et al. 1995; Mohammed and Awatif 1998; Kahyaoglu and Kaya 2006; Elleuch et al. 2007).

The chemical composition of sesame seed meal varies according to the method of processing mechanical or solvent extraction. Dry matter (DM) contents of sesame seed meal ranged from 83 to 96% while CP, ash, ether extract, nitrogen-free extract (NFE), and crud fiber contents ranged from 23 to 46%, 7.5 to 17%, 1.4 to 27%, 25 to 32%, and 5 to 12%, respectively, as recorded by (FAO 1990; Hejazi and Abo Omar 2009; Mulugeta and Gebrehiwot 2013; Mahmoud and Bendary 2014).

Inclusion of sesame seed meal in calve rations had positive effects on its performance as noted by Ryu et al. (1998a). Also, Obeidat et al. (2009) found that when soybean meal was replaced by sesame meal (46% CP, DM basis), finishing performance improved and cost of production diminished without any detrimental effect on carcass characteristics or meat quality of Awassi lambs. Also, Abo Omar (2002) reported that the sesame oil cake addition at 10% and 20% improved growth performance (ADG: DMI, and cost of feed/kg gain) of lambs.

So, this work aimed to study the impact of partial or complete replacement of soybean meal by sesame seed meal in growing Barkki lamb rations on their growth performance, digestion coefficients, water intake, ruminal fermentation, and economic evaluation.

Methods

The present study was carried out at the Sheep and Goats Units in El-Nubaria Experimental and Production Station at El-Imam Malik Village, which belongs to the Animal Production Department, National Research Centre, Dokki, Cairo, Egypt.

Animals and feed

Fifteen growing male Barki lambs aged 5–6 months (18.50 ± 0.98 kg) were used to investigate the influence of replacing soybean meal (SBM) that was incorporated at 16% of control ration by sesame meal (SM) at 50% or 100% (equal to 0%, 8% and 16% of total ration contents) on feed and water intakes, nutrient digestibility, growth performance, some rumen fluid parameters and economic evaluation. The animals were randomly assigned to three experimental groups (five lambs in each treatment).

Experimental animals were housed in semi-open pens and fed as group feeding for 91 days and the experimental rations received would cover the requirements of total digestible nutrients and protein for growing sheep according to the NRC (1985).

-

R1: First (1st) complete feed mixture expressed as control ration contained 16% soybean meal.

-

R2: Second (2nd) complete feed mixture replaced 50% of soybean meal (SBM) by sesame meal (SM) (8% SBM + 8% SM).

-

R3: Third (3rd) complete feed mixture completely replaced 100% of SBM by SM (16% SM).

Daily amounts of complete feed mixtures (CFM) were adjusted every 2 weeks according to body weight changes. Rations were offered twice daily in two equal portions at 800 and 1400 h, while feed residues were daily collected, sun dried, and weekly weighed. Fresh water was freely available at all times in plastic containers. Individual body weight change was weekly recorded before the morning meal.

Digestibility trials

At the end of the feeding trial, four animals from each group were housed in individual metabolic cages to calculate both digestibility coefficients and nutritive values.

A different tested CFM was offered at 8.00 a.m. and water was available at all times.

The digestibility trial continued for 14 days as a preliminary period followed by 7 days for feces only collection.

During the collection period, feces were quantitatively collected from each animal once a day at 7.00 a.m. before feeding. Actual quantity of feed intake consumption was recorded. A sample of 10% of the collected feces from each animal was sprayed with 10% sulphoric acid and 10% formaldehyde solutions and dried at 60 °C for 48 h. Samples were mixed and stored for chemical analysis. Composite samples of feed and feces were finely ground prior to analysis.

The nutritive values expressed as the total digestible nutrient (TDN) and digestible crude protein (DCP) of the experimental rations was calculated by classical method that was described by Abou-Raya (1967).

Rumen fluid parameters

Rumen fluid samples were collected from all animals at the end of the digestibility trial at 3 h post feeding via stomach tube and strained through four layers of cheesecloth. Samples were separated into two portions, the first portion was used for immediate determination of ruminal pH and ammonia nitrogen concentration, while the second portion was stored at − 20 °C after adding a few drops of toluene and a thin layer of paraffin oil till analyzed of total volatile fatty acids (TVFAs).

Analytical procedures

Chemical analysis of ingredients, CFM, and feces samples were analyzed according to AOAC (2005) methods.

Ruminal pH was immediately determined using a digital pH meter. Ruminal ammonia nitrogen (NH3-N) concentrations were determined applying NH3 diffusion technique using Kjeldahle distillation method according to AOAC (2005). Meanwhile, ruminal TVFA concentrations were determined by steam distillation according to Warner (1964).

Gross energy (Kcal/Kg DM) calculated according to Blaxter (1968). Each g CP = 5.65 Kcal, g EE = 9.40 Kcal, and g CF and NFE = 4.15 Kcal.

Digestible energy (DE) was calculated according to NRC (1977) by applying the following equation: DE (kcal/kg DM) = GE × 0.76.

Non-fibrous carbohydrates (NFC) were calculated according to Calsamiglia et al. (1995) using the following equation: NFC = 100 − {CP + EE + Ash + NDF}.

Neutral detergent fiber (NDF), acid detergent fiber (ADF), and acid detergent lignin (ADL) were also determined according to Goering and Van Soest (1970) and Van Soest et al. (1991). Meanwhile, hemicellulose and cellulose content were calculated as follows:

Economic evaluation

Calculation of economical efficiency of tested complete feed mixtures that was used in the present work depended on both local market price of ingredients and price of sheep live body weight.

Statistical analysis

Collected data on the initial and final live body weight, total body weight gain, average daily gain, feed and water intake, feed conversion, and ruminal fermentation were subjected to statistical analysis as one way analysis of variance according to SPSS (2008). Duncan’s Multiple Range test (Duncan 1955) was used to separate means when the dietary treatment effect was significant according to the following model: Yij = μ + Ti + eij:

where Yij = observation; μ = overall mean; Ti = effect of experimental rations for i = 1–3, 1 = R1 contained 16% soybean meal and considered the control, 2 = R2 replaced 50% of soybean meal in the control ration by sesame meal, and 3 = R3 complete replacement (100%) of soybean meal in the control ration by sesame meal; and eij = the experimental error.

Results

Illustrated data in Table 1 shows that sesame meal (SM) considered a good source of protein (36.12%) that equals 82.09% of the portion of protein that found in soybean meal (SBM, 44%). However, SSM was superior in their contents of EE, hemicellulose, and cellulose (5.43, 13.94, and 21.59%, respectively) in comparison with the SBM that contained 0.65, 10.54, and 20.82%, respectively, of the same nutrients mentioned above.

Partial and complete replacement of SBM by SM (50 and 100%, respectively) lead to a decrease in the total price (L.E/ton) by 11.00% and 21.68% for R2 and R3, respectively, in comparison with the control (Table 2).

Inclusion SM in tested ration realized a slight decrease in the contents of CP and NFE that ranged from 16.74 to 16.25% for CP and 61.35 to 57.35%, respectively. Also, NFC, GE, and DE contents were also decreased (Table 2).

Meanwhile, an increase in their contents of CF, EE, and ash ranged from 10.51 to 12.87%, 2.94 to 3.56%, and 8.46 to 9.97%, respectively. NDF, ADF, ADL, hemicellulose, and cellulose also increased by incorporation of SM in rations.

Digetibility and nutritive values

Dietary treatments had no significant effect on all digestibility and TDN value (Table 3). The DCP was significantly (P < 0.05) reduced in R3 while the DCP in the control (R1) and R2 was similar (P > 0.05).

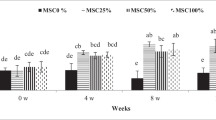

Productive performance

Dietary treatment increased (P < 0.05) total body weight gain and average daily gain. Both total body weight gain and average daily gain increased (P < 0.05) while increasing the level of replacement of soybean meal by sesame seed meal (Table 4).

Incorporation of sesame seed meal in sheep rations had no significant effect (P > 0.05) on all feed intake determined (g/h/day, g/kgW0.75, and Kg/100 kg live body weight of dry matter, crude protein, digestible crude protein, non-fibrous carbohydrates and total digestible nutrients intake or expressed as kcal/h/day, kcal/kgW0.75 and Mcal/ 100 kg live body weight of gross and digestible energy) (Table 4).

Feed conversion expressed as gram intake/gram gain of dry matter, crude protein, digestible crude protein, non-fibrous carbohydrates, and total digestible nutrient or that expressed as kilocalorie intake/gram gain of gross, and digestible energy were improved (P < 0.05) with increasing level of replacement of soybean meal by sesame meal (Table 4).

Drinking water

Water consumption was not significantly (P > 0.05) affected by the dietary treatment (Table 5).

Ruminal fluid parameters

Replacement soybean meal (SBM) by sesame meal (SM) increased (P < 0.05) the ruminal pH values from 5.60 in control (R1) to 5.98 and 6.05 in R2 and R3, respectively, (Table 6). On the other hand, the NH3-N and TVFAs were not affected (P > 0.05) by the dietary treatment.

Economic evaluation

The economic evaluation of the experimental groups is shown in Table 7. Daily profit above feeding cost was gradually increased in lambs fed R2 (7.371 LE) and (8.150 LE) R3 compared to R1 (4.984 LE) as a result of increasing ADG.

Feed cost (LE per kilogram gain) was depressed by 27.47% and 38.44% for R2 and R3, respectively, compared to control (R1). In addition, relative economical efficiency improved for R2 (147.9%), and 163.5% for R3 in comparison with control (R1).

Discussion

Chemical composition of sesame meal varies according to the method of processing (FAO 1990; Ryu et al. 1998b; Abo Omar 2002; Hejazy 2008; Hejazi and Abo Omar 2009; Mulugeta and Gebrehiwot 2013; Mahmoud and Bendary 2014; Mahmoud and Ghoneem 2014).Variations in chemical composition of different tested rations related to different portions of ingredients used in ration formulation and also related to differences in their chemical analysis.

Results concerning the digestibility and the nutritive values are in harmony with those obtained by Ahmed and Abdalla (2005) who noticed that replacing 50% of cotton seed cake by sesame seed cake in yearling sheep had no effect on digestibility and TDN value. Also, the present results in harmony with those noted by Mahmoud and Ghoneem (2014) who noted that there were no significant (p > 0.05) difference in the digestibility of DM, CF, NFE, NDF, cellulose, and hemicellulose among rations that contained 50% Nigella sataiva meal, 50% sesame seed meal, or 25% Nigella sataiva meal + 25% sesame seed meal, in comparison with the control. While there were insignificant decreases in digestibility of OM, CP, and ADF for lactating buffaloes that received 50% Nigella sataiva meal or 50% sesame seed meal. However, the previous values decreased (P < 0.05) for lactating buffaloes fed 25% Nigella sataiva meal + 25% sesame seed meal containing rations. Also, Mahmoud and Ghoneem (2014) noted that buffaloes which received concentrate feed mixture contained 50% sesame meal insignificantly decreased DCP content comparing with those fed control ration. On the other hand, Fitwi and Tadesse (2013) noticed that feeding growing sheep diets containing 0, 150, 200, 250, and 300 g day−1 feed ingredient did not affect DM, OM, CP, and CF digestibility of rations and in their TDN. Also, digestibility of DM was not affected by the inclusion of sesame oil cake in Awassi lamb diets as reported by Abo Omar (2002). In addition, similar results were observed in bull calves when fed rations containing sesame oil cake as noted by (Khan et al. 1998) and in goats as reported by (Hossain et al. 1989). Meanwhile, CP and crude fiber digestibility was highest (P < 0.05) for the diet containing 20% sesame oil cake (Abo Omar 2002). On the other hand, Yasser et al. (2015) reported that apparent digestibility of all nutrients OM, CP, CF, EE, and NFE all were increased (P < 0.05) with sesame seed meals in rabbits compared with the control diet.

Our results of growth performance that is published in Table 4 were in agreement with Abo Omar (2002) who showed that the average weight of Awassi lambs was higher for lambs fed 20% sesame oil cake containing ration in comparison with the control group and lambs that received 10% sesame oil cake containing ration, while the average daily gain in the 10 and 20% sesame oil cake groups was higher (P < 0.05) than in the control group. Moreover, Hassan et al. (2013) concluded that incorporation of sesame cake up to 20% in Sudan desert sheep rations caused satisfactory feedlot performance. Treatment had no effect (P < 0.05) on TDN, and that may be related to the DMI and digestibility of all nutrients which was not affected (P < 0.05) by treatment.

Dry matter and the other nutrient intake insignificantly reduced when sesame oil cake incorporated in Awassi lamb rations at 0, 10, and 20% of ration formula. These reductions in dry matter intake were recorded by 4 and 2% for lambs consuming rations containing 10 and 20% sesame oil cake, respectively, compared with the control (Abo Omar 2002). A similar trend was observed in protein intake. However, intake of fiber and fat increased (P < 0.05) by feeding sesame oil cake. On the other hand, the DM intake and other nutrients were similar to intake observed in many fattening studies utilizing different types of diets (Hammad 2001).

Abo Omar (2002) found that feed conversion ratio were improved (P < 0.05) when sesame oil cake was introduced in Awassi lamb rations at 10 and 20% of ration formula. Also, the improvement of feed efficiency was in agreement with previous work with broilers and layers fed sesame seed cake (Jacob et al. 1996). On the other hand, these findings were in accordance to Lutfi (1983), Hassan (2005), Suliman and Babiker (2007), and Hassan et al. (2013) who reported significant differences in feed conversion for sheep that received sesame cake meal up to 20%.

Increasing water intake in R2 and R3 compared R1 may be due to different percent of berseem hay (R1 24%, R2 30%, and R3 36%) or, may be related to the increased percentage of ash, CF, and EE contents in R2 (9.22%, 11.70%, and 3.25%, respectively) and R3 (9.97%, 12.87% and 3.56%, respectively) compared to control that contained ash 8.46%, CF 10.51%, and EE 2.94% as presented in Table 2. DMI and water intake are positively associated (NRC 1996), so ash is not the only constituent of dry matter in the feed, therefore, the ash contents could not be the sole cause of the changes in the water consumption.

Also, Omer et al. (2012) noted that sheep received rations composed of 50% concentrate feed mixture + 50% of peanut vein hay, beans straw, kidney beans straw, or linseed straw increased (P < 0.05) drinking water compared to control group that offered ration composed of (50% concentrate feed mixture + 50% berseem hay) Also, they recorded that the corresponding values of drinking water were 3088, 3742, 4650, 3660, and 3038 ml/h/day for control and the other four experiment groups mentioned above. On the other hand, Ahmed and Abdalla (2005) showed that replacing 50% of cotton seed cake (CSC) by sesame seed cake (SSC) in yearling sheep had no effect on water intake (3.04 vs. 3.00 l/kg DM intake) for CSC and SSC, respectively; we think that ash content in the two sources in the same range had not caused any adverse effect on quantity water consumption.

Ahmed and Abdalla (2005) noted that replacing 50% of cotton seed cake (CSC) with sesame seed cake (SSC) in yearling sheep had no effect on ruminal pH and total volatile fatty acids (TVFAs) concentration; however, NH3-N concentration was decreased (P < 0.05) at the same time of take with the rumen liquor samples in our study (3 h post feeding). The corresponding values were 6.44 vs. 6.54 for ruminal pH, and 33.7 vs. 29.6 for TVFAs and 56.7 vs. 30.76 for ammonia nitrogen (NH3-N) concentration for the group sheep which received CSC and SSC, respectively. The optimal value for microbial growth and digestion of fiber pH was 6.0–7.0 (Weimer 1996). Mold and Orskov (1984) demonstrated that cellulose digestion was limited when ruminal pH was below 6.0. Staples et al. (1984) noted that the optimum pH value for rumen cellulolytic bacteria was ranged “between” 5.8 and 6.3. This range was almost in the same range to that obtained in our study. On the other hand, both Slyter et al. (1979) and Pan et al. (2003) noted that increased ruminal NH3-N (22.5 mg %) might increase ruminal pH, TVF’s production, and stimulated cellulolytic bacteria activity in the rumen. Also, Kanjanapruthipong and Leng (1998) showed that protozoan, fungal, and bacterial populations in the rumen were influenced by the levels of ruminal NH3-N.

The cost per kilogram gain was highest for lambs fed the control feed, meanwhile, the incorporation of sesame oil cake reduced cost of gain. This was related to lower costs of rations containing sesame oil cake (Abo Omar 2002). On the other hand, Fitwi and Tadesse (2013) showed that using 300 g DM of sesame seed cake was potentially more feasible and economically beneficial for growing sheep. Also, Mahmoud and Bendary (2014) noted that the use of sesame seed meal reduced feed cost, and therefore it can be used to improve total revenue, net revenue, economic efficiency, and relative economic efficiency in ration on performance of growing lambs and calves. Moreover, Mahmoud and Ghoneem (2014) reported that there was a decrease in the feed cost per 1 kg 7% fat corrected milk (FCM) in Egyptian lactating buffaloes fed ration composed of (50% roughage and 50% concentrate feed mixture that contained 50% sesame seed meal) in comparison with control ration. Meanwhile, El-Nomeary Yasser et al. (2015) found that incorporation sesame seed meal in rabbit diets supplemented with black cumin, mustard, sesame, and rocket seed meals improved relative economic efficiency that reached to 140% in comparison with the control diet that considered 100%.

Conclusion

Sesame seed meal can be a successful partial or complete replacement soybean meal in lamb rations without any deleterious effect and while improving economic efficiency.

Availability of data and materials

“Not applicable” for this study

Abbreviations

- ADF:

-

Acid detergent fiber

- ADG:

-

Average daily gain

- ADL:

-

Acid detergent lignin

- AOAC:

-

Official Methods of Analysis

- CF:

-

Crude fiber

- CFM:

-

Complete feed mixtures

- CP:

-

Crude protein

- CSC:

-

Cotton seed cake

- DCP:

-

Digestible crud protein

- DE:

-

Digestible energy

- DM:

-

Dry matter

- DMI:

-

Dry matter intake

- EE:

-

Ether extract

- FAO:

-

Food and Agriculture Organization

- FC:

-

Feed conversion

- FI:

-

Feed intake

- FW:

-

Final weight

- GE:

-

Gross energy

- IW:

-

Initial weight

- LBW:

-

Live body weight

- LE:

-

Egyptian pound

- NDF:

-

Neutral detergent fiber

- NFC:

-

Non-fibrous carbohydrates

- NFE:

-

Nitrogen-free extract

- NH3-N:

-

Ammonia nitrogen

- NRC:

-

National Research Council

- OM:

-

Organic matter

- R1 :

-

Control ration contained 16% soybean meal

- R2 :

-

Replaced 50% of soybean meal by sesame meal

- R3 :

-

Replaced 100% of soybean meal by sesame meal

- SBM:

-

Soybean meal

- SM:

-

Sesame meal

- SPSS:

-

Statistical package for Social Sciences

- SSC:

-

Sesame seed cake

- TBWG:

-

Total body weight gain

- TDN:

-

Total digestible nutrients

- TVFAs:

-

Total volatile fatty acids

References

Abo Omar J (2002) Effects of feeding different levels of sesame oil cake on performance and digestibility of Awassi lambs. Small Rumin Res 46:187–190

Abou-Raya AK (1967) Animal and poultry nutrition, 1st edn Pub. Dar El-Maarif, Cairo (Arabic text book)

Ahmed MMM, Abdalla HA (2005) Use of different nitrogen sources in the fattening of yearling sheep. Small Rumin Res 56:39–45

AOAC (2005) Official methods of analysis, 18th edn. Association of Official Analytical Chemists, Washington, DC

Blaxter KL (1968) The energy metabolism of ruminants, 2nd edn. Charles Thomas Publisher. Spring field, Illinois

Bonos E, Kargopoulos A, Basdagianni Z, Mpantis D, Taskopoulou E, Tsilofiti B, Nikolakakis I (2017) Dietary sesame seed hulls utilization on lamb performance, lipid oxidation and fatty acids composition of the meat. Anim Hus Dairy Vet Sci 1(1):1–5

Calsamiglia S, Stem MD, Frinkins JL (1995) Effects of protein source on nitrogen metabolism in continuous culture and intestinal digestion in vitro. J Anim Sci 73:1819

Duncan DB (1955) Multiple rang and multiple F-Test. Biometrics 11:1–42

Elleuch M, Besbes S, Roiseux O, Blecker C, Attia H (2007) Quality characteristics of sesame seeds and by-products. Food Chem 103:641–650

El-Nomeary Yasser AA, El-Kady RI, El-Shahat AA (2015) Effect of some medicinal plant seed meals supplementation and their effects on the productive performance of male rabbits. Int J Chem Tech Res 8(6):401–411

FAO (1990) Guide to Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) documents (website).

FAO (2014) Food and agricultural commodities production: countries by commodity.

Fitwi M, Tadesse G (2013) Effect of sesame cake supplementation on feed intake, body weight gain, feed conversion efficiency and carcass parameters in the ration of sheep fed on wheat bran and teff (Eragrostis teff) straw. Momona Ethiopian J Sci 5:89–106

Goering HK, Van Soest PJ (1970) Forge fiber analysis (apparatus, reagents, procedure and some applications). In: Agric. Hand book 379. USDA, Washington, DC

Hammad W (2001) Evaluation of Awassi lambs fattening systems in Palestine. Master of science thesis. A Najah National University, the Palestnian National Authority, Nablus, pp 34–37

Hassan EH (2005) The effects of feeding Rossel (Hibiscus sabdarifa) seeds on meat quality and carcass characteristics of Sudan desert sheep. M. Sc. Thesis. Faculty of Animal Production, University of Gezira, Sudan.

Hassan HE, Elamin KM, Elhashmi YHA, Tameem Eldar AA, Elbushra ME, Mohammed MD (2013) Effects of feeding different levels of sesame oil cake (Sesamum indicum L.) on performance and carcass characteristics of Sudan desert sheep. J Anim Sci Adv 3(2):91–96

Hejazi A, Abo Omar JMA (2009) Effect of feeding sesame oil cake on performance, milk and cheese quality of Anglo Nubian goats. Hebron Univ Res J 4(1):81–91

Hejazy AMA (2008) Effect of feeding sesame oil cake on performance and cheese quality of Anglo-Nubian goats. MSc. Animal Production, Faculty of Graduate Studies. An-Najah National University, Nablus

Hossain MM, Huq MA, Saadulla M, Akhtar S (1989) Effect of supplementation of rice straw diets with sesame oil cake, fish meal and mineral mixture on dry matter digestibility in goats. Indian J Ani Nutr 6(1):44–47

Indexmundi (2016a) March Soybean meal monthly price https://www.indexmundi.com/commodities/?commodity=soybean-meal.

Indexmundi (2016b) March Maize (corn) monthly price https://www.indexmundi.com/commodities/?commodity=corn.

Indexmundi (2016c) March Barley Monthly Price https://www.indexmundi.com/commodities/?commodity=barley.

Jacob JP, Mitran BN, Mbugua PN, Blair R (1996) The feeding value of Kenyan sorghum, sunflower seed cake and sesame seed cake for broilers and layers. Anim Feed Sci Technol 61:41–56

Kahyaoglu T, Kaya S (2006) Modeling of moisture, color and texture changes in sesame seeds during the conventional roasting. J Food Eng 75:167–177

Kanjanapruthipong J, Leng RA (1998) The effects of dietary urea on microbial populations in the rumen of sheep. Asian Australas J Anim Sci 11:661–672

Khan MJ, Shahjalal M, Rashid MM (1998) Effect of replacing oil cake by poultry excreta on growth and nutrient utilization in growing bull calves. Asian Australas J Anim Sci 11:385–390

Lawrence JD, Mintert J, Anderson JD, Anderson DP (2010) Feed grains and livestock: impacts on meat supplies and prices. Choices Agricultural & Applied Economics Association

Lutfi AA (1983) The performance of desert sheep fed protein and energy from different sources. M. Sc. Thesis (Animal Production). University of Khartoum, Sudan

Mahmoud AEM, Bendary MM (2014) Effect of whole substitution of protein source by Nigella sativa meal and Sesame seed meal in ration on performance of growing lambs and calves. Global Vet 13(3):391–396

Mahmoud AEM, Ghoneem WMA (2014) Effect of partial substitution of dietary protein by Nigella sataiva meal and sesame seed meal on performance of Egyptian lactating buffaloes. Asian J Anim Vet Adv 9(8):489–498

Mohammed HMA, Awatif II (1998) The use of sesame oil unsaponifiable matter as a natural antioxidant. Food Chem Toxicol 62:269–276

Mold FL, Orskov ER (1984) Manipulation of rumen fluid pH and its influence on cellulolysis in Sacco, dry matter degradation and the rumen microflora of sheep offered either hay or concentrate. Anim Feed Sci Technol 10:1–14

Mulugeta F, Gebrehiwot T (2013) Effect of sesame cake supplementation on feed intake, body weight gain, feed conversion efficiency and carcass parameters in the ration of sheep fed on wheat bran and teff (Eragrostis teff) straw. Momona Ethiop J Sci 5(1):89–106

Nikolakakis I, Bonos E, Kasapidou E, Kargopoulos A, Mitlianga P (2014) Effect of dietary sesame seed hulls on broiler performance, carcass traits and lipid oxidation of the meat. Europ Poult Sci 78(28):1-9

NRC National Research Council (1977) Nutrient requirements of rabbits. National Academy of Science, Washington, D.C

NRC National Research Council (1985) Nutrient Requirements of Sheep, 6th edn. National Research Council, National Academy Press, Washington, DC

NRC National Research Council (1996) Nutrient Requirements of Beef Cattle, 7th edn. Natl. Acad. Press, Washington, D.C

Obeidat BS, Abdullah AY, Mahmoud KZ, Awawdeh MS, AL-Beitawi NZ, AL-Lataifeh FA (2009) Effects of feeding sesame meal on growth performance, nutrient digestibility, and carcass characteristics of Awassi lambs. Small Rumin Res 82:13–17

Omer HAA, Tawila MA, Gad SM (2012) Feed and water consumptions, digestion coefficients, nitrogen balance and some rumen fluid parameters of Ossimi sheep fed diets containing different sources of roughages. Life Sci J 9(3):805–816

Pan J, Suzuki T, Koike S, Ueda K, Kobayashi Y (2003) Effect of urea infusion into the rumen on liquid-and particle associated fibrolytic enzyme activities in steers fed low quality grass hay. Anim Feed Sci Technol 104:13–27

Ryu YW, KO YD, Lee SM (1998a) Effects of mixing ratio of apple pomace, sesame oil meal and cage layer excreta on feed quality of rice straw silage. Korean J Anim Sci 40(3):245–254

Ryu YW, Ko YD, Lee SM (1998b) Effect of feeding rice straw silage made with apple pomace. Korean J Anim Sci 40(3):235–244

Slyter LL, Satter LD, Dinius DA (1979) Effect of ruminal ammonia concentration on nitrogen utilization by steers. J Anim Sci 48:906–912

SPSS (2008) Statistical Package for Social Sciences, Statistics for Windows, Version 17.0. Released 2008. SPSS Inc, Chicago

Staples CR, Fernando RL, Fahey GC, Berger LL, Jaster EH (1984) Effect of intake of a mixed diet by dairy steers on digestion events. J Dairy Sci 67:995

Stillman R, Haley M, Mathew K (2009) Grain prices impact entire livestock production cycle. Amber Waves, USDA Economic Research Service, pp 24-27. https://www.ers.usda.gov/amber-waves/2009/march/grain-prices-impact-entire-livestock-production-cycle/.

Suliman GM, Babiker SA (2007) Effect of diet-protein source on lamb fattening. Res J Agric Biol Sci 5:403–408

Van Soest PJ, Robertson JB, Lewis BA (1991) Methods for dietary fiber, neutral detergent fiber and non starch polysaccharides in relation to animal performance. J Dairy Sci 74:3583–3597

Warner AC (1964) Production of volatile fatty acids in the rumen, methods of measurements. Nutr Abstr Rev 34:339

Weimer PJ (1996) Why do not ruminal bacteria digest cellulose faster? J Dairy Sci 79:1496–1502

Yoshida H, Shigezaki J, Takagi S, Kajimoto C (1995) Variations in the composition of various acyl lipids, tocopherols and lignans in sesame seed oils roasted in a microwave oven. J Sci Food Agric 68:407–415

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by scientific project section, National Research Centre (P11030120) “Maximizing the productivity and quality traits of some oil crops (flax, peanut and sunflower) grown under newly reclaimed lands” and (P11030122) “Increasing productivity of some un-traditional crops and crop residues for animal feeding”

Funding

Project No. (P11030120) under title “Maximizing the productivity and quality traits of some oil crops (flax, peanut and sunflower) grown under newly reclaimed lands” and project No. (P11030122) under title “Increasing productivity of some un-traditional crops and crop residues for animal feeding”. National Research Centre.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HA-AAO cooperated in the plane of work, field work, chemical analysis, data calculations, statistical analyses of data, and writing of the MS and helped in the publication. SMA cooperated in the plane of work, field work, and revision of the MS and helped in the publication. SSA-M cooperated in the plane of work and field work and followed the publication with the journal (corresponding author). BAB contributed in providing facilities. MFEK provided experimental animals and facilities. EHE cooperated in the chemical analysis and blood sample analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

“Not applicable” for this study

Consent for publication

“Not applicable” for this study

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Omer, H.A.A., Ahmed, S.M., Abdel-Magid, S.S. et al. Nutritional impact of partial or complete replacement of soybean meal by sesame (Sesamum indicum) meal in lambs rations. Bull Natl Res Cent 43, 98 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42269-019-0140-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s42269-019-0140-8