Abstract

Anorexia nervosa, with the highest mortality rate among psychiatric diseases, is characterized by low body mass index, fear of weight gain, and disturbed body image. Even though multiple drugs have been proposed for the treatment of anorexia nervosa, current treatment modalities include nutritional support and psychotherapy. In this study, our aim is to analyze the efficiency and possible adverse effects of olanzapine, an atypical anti-psychotic drug, in the treatment of anorexia nervosa. The studies investigating the efficiency and possible adverse effects of olanzapine in anorexia nervosa have been searched by using 3 databases (Embase, PubMed, and Cochrane Library). DerSimonian-Laird random effects meta-analyses have been used in the statistical analysis. Effect of olanzapine treatment in accordance with the duration and dosage of drug have been analyzed by the determination of 95% confidence intervals (p value < 0.05 is considered as statistically significant). Despite the presence of some contradictory studies, olanzapine treatment has been found beneficial in anorexia nervosa. In addition, analysis reveals that statistically significant beneficial effect of olanzapine treatment is used at high doses and for short duration. Possible side effects include neuroleptic malignant syndrome, hypoglycemia, and heart block in patients suffering from anorexia nervosa. Even though there is obvious need for more comprehensive further studies, current literature favors olanzapine treatment. The efficiency of olanzapine is considered to be related to changes in dopaminergic and serotonergic system in anorexic patients both in terms of neurotransmitter levels and receptor activity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Anorexia nervosa (AN), classified as an eating disorder by DSM-V along with bulimia nervosa and eating disorder non-otherwise specified, is characterized by body weight less than 85% of that expected for age and height, disturbances in body image, amenorrhea, and fear of weight gain [1, 2]. Incidence of AN has been reported as 0.9-2% in females and 0.3% in males which remained stable over the last 50 years except an increase in females between ages 15-24 [3, 4]. Comorbid psychiatric conditions including obsessive-compulsive disorder, major depression, and anxiety disorders have commonly been reported [5, 6]. AN is considered as the psychiatric disease with the highest mortality rate mostly attributable to its organic outcomes [5, 6]. Current treatment guidelines for AN include nutritional support and psychotherapy such as cognitive remediation therapy (CRT), dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), and psychodynamic psychotherapy that can be delivered in inpatient or outpatient setting.

Many drugs have been proposed as a pharmacotheraupetic treatment option for AN while none has been approved by US Food and Drug Administration. Major candidates are antidepressants, anti-psychotics, mood stabilizers, and anti-obesity drugs (i.e., orlistat) [7]. Rationale behind trial of those medications is the altered serotonergic system in patients with AN which may be the primary pathophysiology [8,9,10,11]. Despite lack of sufficient evidence regarding efficiency and safety, they are widely prescribed mostly due to comorbid psychiatric conditions in the patients [12]. Bupropion has been associated with increased seizure risk in AN patients, thus, the use of buproprion is contraindicated. Additionally, the use of monoamine oxidase (MAO) or tricyclic anti-depressants (TCA) has not recommended due to insufficient beneficial effects [7].

Olanzapine, an atypical anti-psychotic inhibiting serotonergic (5-HT2) and dopaminergic (D2) system, has been utilized in the treatment of major depression and certain mood disorders including schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Many trials of olanzapine in AN patients in combination with psychotherapy and nutritional support have been performed with promising outcomes. Known adverse effects of olanzapine are dizziness, orthostatic hypotension, hypercholesterolemia, hypertriglyceridemia, hyperglycemia, weight gain, extra-pyramidal symptoms, dry mouth, hyperprolactinemia, and insomnia. In this literature review, our aim is to evaluate the efficiency and safety of olanzapine treatment in patients with AN.

Methods

Literature search

Studies investigating the possible role of olanzapine in the treatment of anorexia nervosa have been searched by using 3 databases (PubMed, Cochrane Library, and Embase) by utilizing Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) which are listed as follows “anorexia nervosa”, “olanzapine” and “antipsychotic agents”. Reference lists of each study have been further assessed to minimize the risk of overlooking any relevant study.

Study selection

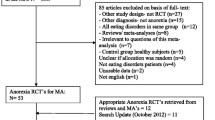

Abstracts of the studies found in the literature search have been analyzed by two authors independently in order to assess their eligibility for literature review. Studies that fit to the inclusion criteria of our literature review have further been analyzed. Details of the literature review and study selection process have been demonstrated in Fig. 1 [13]. Inclusion criteria for article selection are as follows:

- 1.

The study should be conducted with patients that are diagnosed with anorexia nervosa and treated with olanzapine.

- 2.

Participants of the studies should be diagnosed with AN according to DSM-III, DSM-III-R, DSM-IV, DSM-V, Russell, or ICD-10.

- 3.

The article should be published in a peer-reviewed journal between 2009 and 2019 in English.

PRISMA flow diagram of the process of study selection for the systematic review [13]

Quality assessment

After the determination of eligible studies, each study has been evaluated by both authors independently to assess their “level of evidence” established by Melnyk at “Evidence-based practice in nursing & healthcare: a guide to best practice” (criteria for level of evidence assessment is available at Table 1) [14]. In addition, each study has been further assessed depending on the presence of the control group, size of study, participant selection criteria, presence of comorbid conditions in the participants, consistency of data from each study, and evaluation criteria for efficiency.

Statistical analysis

We used weighted mean difference (WMD) in order to point estimate each study which is an indicator of the treatment efficiency in terms of change in body mass index (BMI) since studies analyzed in the review contain a variable number of participants [15]. We determined their 95% confidence intervals and their pooled effects by using DerSimonian-Laird random-effects meta-analyses as implemented in Comprehensive Meta-analysis V 2.0 [16]. T test is implemented to compare the efficiency of treatment with the control groups.

Subgroup analysis

We determined prior hypotheses for subgroup analysis in order to analyze the possible source of differences among the study results which includes trial duration (8 weeks or less vs. more than 8 weeks) and dose of drug (low dose vs. high dose). We performed t test to assess the statistical significance of the differences and p value below 0.05 are considered as statistically significant.

Results

The literature review evaluates 24 studies comprised of 5 randomized controlled trials, 8 case-control studies, and 11 case reports (Table 2). Among them, a total of 10 studies comprised of randomized controlled trials and case-control studies are found eligible for statistical analysis and quantitative evaluation.

Qualitative evaluation

Hansen (1999) demonstrated successful utilization of olanzapine, with an average of 1 kg/week weight gain, in a 49-year-old female patient with obsessive-compulsive disorder who received antidepressant treatment before, including chlorpromazine [17]. A case series study with two patients suffering from anorexia nervosa over 5 years with multiple hospitalizations at the ages of 15 and 27 was the first study exploring the efficiency of olanzapine in patients with no other comorbidities [18]. Both patients gained over 1 kg/week (> 3% of their initial body weights), 1.2 kg/week, and 1.7 kg/week respectively, with 5 mg/day olanzapine treatment [18]. Another case series study demonstrating possible beneficial effects of olanzapine in the treatment of AN included a 50-year-old female without any comorbidity and a 34-year-old female with borderline personality disorder [19]. Later on, many other cases have been reported in adolescents and adults.

The first case-control study was performed in 2002 with 14 patients treated with 10 mg/day olanzapine for 10-week period [21]. Ten patients gained 4 kg on average while the remaining four patients demonstrated a weight loss of approximately 1 kg [21]. The first randomized controlled trial comparing the efficiency of olanzapine versus chlorpromazine in AN patients illustrated no statistically significant difference in terms of weight gain [41]. Patients treated with olanzapine showed statistically less anorexic rumination behavior [41]. However, the primary limitation of this study is the lack of placebo control group [41]. First placebo-controlled RCT performed in 2007 including 10 participants receiving olanzapine (2.5 mg/day olanzapine for 2 months and 5 mg/day for 4 months) and 10 participants receiving placebo showed the inefficiency of olanzapine [24]. Both patient groups received behavioral therapy and nutritional support [24]. On the other hand, another placebo-controlled RCT performed with a total of 34 AN patients demonstrated a statistically significant beneficial effect of olanzapine in terms of weight gain [25]. Patients receiving olanzapine demonstrated 4-point increase in BMI, on average, (standard deviation = 0.99) while the placebo group showed 3 point increase in BMI (standard deviation = 1.32) [25]. Multiple other studies including case control and RCT have been performed over the last years with various outcomes.

Safety profile of olanzapine treatment in AN has also been a point of interest in our study. There are few case reports showing adverse effects including neuroleptic malignant syndrome, hypoglycemia, hyperglycemia, morning sedation, and heart block [34, 36, 37, 42]. However, most studies report no significant adverse reactions.

Quantitative evaluation

Weighted mean difference in BMI with olanzapine treatment is 0.435 kg/m2 per month (standard deviation of 0.139), whereas, WMD in BMI with the control group is 0.099 kg/m2 per month (SD = 0.002). No statistically significant difference has been observed at the baseline BMI of control group and olanzapine group (p value > 0.05). Analysis of the effect of olanzapine on BMI compared to the control group reveals statistically significant beneficial effects (p value < 0.01; 95% CI: 0.316, 0.355).

Effect of therapy duration

WMD in BMI with short term olanzapine treatment (≤ 8 weeks) is 0.477 kg/m2 per month (SD = 0.126) while WMD in BMI with long term olanzapine treatment is 0.312 kg/m2 per month (SD = 0.143). Statistical analysis regarding the duration of olanzapine therapy reveals that shorter duration of therapy is more beneficial (p value < 0.01; 95% CI: 0.12949, 0.20051).

Effect of dosage

WMD in BMI with high dose olanzapine treatment (> 5 mg/day) is 0.499 kg/m2 per month (SD = 0.12) while WMD in BMI with low dose olanzapine treatment is 0.295 kg/m2 per month (SD = 0.125). Statistical analysis regarding the dosage of olanzapine demonstrates that a higher dosage of olanzapine is more beneficial (p value < 0.01; 95% CI: 0.17292, 0.23508).

Discussion

Anorexia nervosa, one of the eating disorders listed on DSM-V, is characterized by low BMI, distorted body image, and extreme fear of weight gain that may lead to severe morbidity and mortality, especially among young females. It is important to note that AN is considered to have the highest mortality rate among psychiatric conditions, thus, proper management is crucial. Currently, recommended therapeutic approach includes nutritional support and psychotherapy while there is no FDA-approved pharmacotherapy in the treatment.

Initial rationale behind olanzapine trial in AN patients is the side effect profile of olanzapine including weight gain and common comorbid psychiatric comorbidities of AN. Detection of lower levels of serotonin and its metabolite, 5-hydroxyindolacetic acid, in CSF along with altered binding activities toward serotonergic receptors (5-HT1A and 5-HT2A) in patients with AN leads to trials of many anti-depressant and anti-psychotic drugs in AN treatment [8, 10, 24]. Additional findings regarding lower levels of dopamine and its metabolite (homovanilic acid) in CSF of AN patients along with altered binding activities toward dopaminergic receptors (D2 and D3) provide supportive evidence [8, 10, 24]. Although many other anti-depressant and anti-psychotic drugs have been investigated including risperidone, aripiprazole, fluoxetine, dronabinol, and alprazolam, olanzapine continues to remain as the primary candidate in AN treatment [43,44,45,46,47]. Furthermore, anti-psychotic drugs have shown to led an increase in serum leptin levels which may be an additional beneficiary effect of olanzapine treatment in patients with AN [48].

Growing evidence indicates shared pathophysiological mechanisms between schizophrenia and eating disorders including AN primarily from functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and neuroimaging studies [49, 50]. The primarily affected shared brain areas include anterior fronto-insular cortex and anterior cingulate cortex which are collectively referred as the salience network. Increased activation of the anterior cingulate cortex has been detected in AN patients while administration of sucrose solutions leads to decline in its activity as evidenced by fMRI findings [51]. Similar pattern of involvement has been observed in patients with schizophrenia [52, 53]. Large scale meta-analyses demonstrate that anti-psychotic therapy is associated with alteration of activity of the salience network while following anti-psychotic therapy patients are more likely to have increased activation of the insular cortex when given static food-related images [54, 55]. Although the mechanism is not definitive with current literature and need for further studies is clear, the potential beneficial effects of anti-psychotic therapy such as olanzapine in AN patients may be underlined via correction of shared neurological circuit at the salience network.

Limitation of this review includes a low number of double-blind randomized controlled trials, issues regarding the non-standardized duration of trials and dosages of therapy, and non-standardized therapeutic procedure. Although there is no clear indicator of selection bias in the included studies and both olanzapine and control groups appear to have similar baseline features, possible selection bias in non-blinded studies should not be overlooked and should be considered as another limitation of this review.

To conclude, our findings support the utilization of olanzapine treatment in patients with AN by demonstrating a statistically significant increase in BMI compared to placebo control groups with a relatively tolerable side effect profile. We detected that short term (≤ 8 weeks) and higher doses (> 5 mg/day) of olanzapine treatment is more beneficial in terms of weight gain. However, there is a clear need for large scale, more comprehensive studies regarding the efficiency and safety profile of olanzapine treatment in patients with AN in order to have a better understanding of the subject.

References

APA (American Psychiatric Association). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders-5th Edition (DSM-5). 2013; Washington DC, American Psychiatric Association.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Eating disorders: recognition and treatment. 2017.

Hoek HW. Incidence, prevalence and mortality of anorexia nervosa and other eating disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2006;19:389–94.

Keski-Rahkonen A, Hoek HW, Susser ES, Linna MS, Sihvola E, Raevuori A, et al. Epidemiology and course of anorexia nervosa in the community. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(8):1259–65.

Milos G, Spindler A, Schnyder U. Psychiatric comorbidity and eating disorder inventory (EDI) profiles in eating disorder patients. Can J Psychiatr. 2004;49(3):179–84.

Ulfvebrand S, Birgegård A, Norring C, Högdahl L, Von-Hausswolff-Juhlin Y. Psychiatric comorbidity in women and men with eating disorders results from a large clinical database. Psychiatry Res. 2015;230(2):294–9.

APA (American Psychiatric Association). Practice guidelines for the treatment of patients with eating disorders (3rd ed.). 2016; Washington DC, American Psychiatric Association.

Bailer UF, Frank GK, Henry SE. Exaggerated 5-HT1A but normal 5-HT2A receptor activity in individuals ill with anorexia nervosa. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:1090–10.

Brambilla F, Bellodi L, Arancio C. Central dopaminergic function in anorexia and bulimia nervosa: a psychoneuroendocrine approach. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2001.

Frank GK, Bailer UF, Henry SE. Increased dopamine D2/D3 receptor binding after recovery from anorexia nervosa measured by positron emission tomography and [11C] raclopride. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58:908–12.

Kaye WH, Ebert MH, Raleigh M. Abnormalities in CNS monoamine metabolism in anorexia nervosa. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1984;41:350.

Garner DM, Anderson ML, Keiper CD, Whynott R, Parker L. Psychotropic medications in adult and adolescent eating disorders: clinical practice versus evidence-based recommendations. Eat Weight Disord. 2016;21(3):395–402.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting Items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:7.

Bernadette M, Fineout-Overholt M, Fineout-Overholt E. Evidence-based practice in nursing & healthcare: a guide to best practice. 2005; 10.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539–58.

DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–88.

Hansen L. Olanzapine in the treatment of anorexia nervosa. Br J Psychiatry. 1999;175:592.

La Via MC, Gray N, Kaye WH. Case reports of olanzapine treatment of anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2000;27(3):363–6.

Jensen VS, Mejlhede A. Anorexia nervosa: treatment with olanzapine. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177(01):87.

Mehler C, Wewetzer C, Schulze U, Warnke A, Theisen F, Dittmann RW. Olanzapine in children and adolescents with chronic anorexia nervosa. A study of five cases. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;10(2):151–7.

Powers PS, Santana CA, Bannon YS. Olanzapine in the treatment of anorexia nervosa: an open label trial. Int J Eat Disord. 2002;32(2):146–54.

Ercan ES, Copkunol H, Çýkoðlu S, Varan A. Olanzapine treatment of an adolescent girl with anorexia nervosa. Hum Psychopharmacol Clin Exp. 2003;18(5):401–3.

Dennis K, Le Grange D, Bremer J. Olanzapine use in adolescent anorexia nervosa. Eating and Weight Disorders - Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity. 2006; 11(2).

Brambilla F, Monteleone P, Maj M. Olanzapine-induced weight gain in anorexia nervosa: involvement of leptin and ghrelin secretion? Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2007;32(4):402–6.

Bissada H, Tasca GA, Barber AM, Bradwejn J. Olanzapine in the treatment of low body weight and obsessive thinking in women with anorexia nervosa: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatr. 2008;165(10):1281–8.

Low-dose olanzapine for anorexia nervosa. Brown University Child & Adolescent Psychopharmacology Update. 2010; 12(6).

Leggero C, Masi G, Brunori E, Calderoni S, Carissimo R, Maestro S, Muratori F. Low-dose olanzapine monotherapy in girls with anorexia nervosa, restricting subtype: focus on hyperactivity. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2010;20(2):127–33.

Capasso A, Petrella C, Milano W. P.3.c.006 olanzapine in the treatment of anorexia nervosa: a case report. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2010;20:461.

Attia E, Walsh B, Kaplan A, Yilmaz Z, Gershkovich M, Musante D, Wang Y. Olanzapine versus placebo for out-patients with anorexia nervosa. Psychol Med. 2011;41(10):2177–82.

Kafantaris V, Leigh E, Hertz S, Berest A, Schebendach J, Sterling WM, et al. A placebo-controlled pilot study of adjunctive olanzapine for adolescents with anorexia nervosa. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2011;21(3):207–12.

Pirkalani K, Anorexia N. P02-132 - successful treatment of 27 patients with anorexia nervosa with escalating doses of olanzapine citalopram high dose vitamin b6. Eur Psychiatry. 2011;26:728.

Bangratz S, Moyses M, Mader S, Huemer J, Koubek D, Laczkovics C, Karwautz A. Therapeutic drug monitoring of olanzapine in children and adolescents with anorexia nervosa: a pilot study. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2012; 45(6).

Duvvuri V, Cromley T, Klabunde M, Boutelle K, Kaye W. Differential weight restoration on olanzapine versus fluoxetine in identical twins with anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2012;45(2):294–7.

Haruta I, Asakawa A, Inui A. Olanzapine-induced hypoglycemia in anorexia nervosa. Endocrine. 2014;46(3):672–3.

Kesic A, Lakic A. P.7.d.003 olanzapine in treatment of adolescents with anorexia nervosa. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;24:721.

Alwazeer A, Hussain A, Hickey A, Maclean D. Olanzapine associated heart block in weight-restored anorexia nervosa. Prog Neurol Psychiatry. 2015;19(4):17–8.

Ayyıldız H, Turan S, Gülcü D, Poyraz C, Pehlivanoğlu E, Çullu F, et al. Olanzapine-induced atypical neuroleptic malignant syndrome in an adolescent man with anorexia nervosa. Eat Weight Disord. 2016;21(2):309–11.

Himmerich H, Dornik J, Bentley J, Schmidt U, Treasure J. Olanzapine treatment for patients with anorexia nervosa. Can J Psychiatr. 2017;62(7):506–7.

Spettigue W, Norris M, Maras D, Obeid N, Feder S, Harrison M, et al. Evaluation of the effectiveness and safety of olanzapine as an adjunctive treatment for anorexia nervosa in adolescents: an open-label trial. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2018;27(3):197–208.

Attia E, Steinglass J, Walsh B, Wang Y, Wu P, Schreyer C, et al. Olanzapine versus placebo in adult outpatients with anorexia nervosa: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2019;176(6):449–56.

Mondraty N, Laird Birmingham C, Touyz S, Sundakov V, Chapman L, Beumont P. Randomized controlled trial of olanzapine in the treatment of cognitions in anorexia nervosa. Australasian Psychiatry. 2005;13(1):72–5.

Yasuhara D, Nakahara T, Harada T, Inui A. Olanzapine-induced hyperglycemia in anorexia nervosa. Am J Psychiatr. 2007;164(3):528–9.

Andries A, Frystyk J, Flyvbjerg A, Støving RK. Dronabinol in severe, enduring anorexia nervosa: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Eat Disord. 2014;47:18.

Frank GK, Shott ME, Hagman JO. The partial dopamine D2 receptor agonist aripiprazole is associated with weight gain in adolescent anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2017;5:447.

Hagman J, Gralla J, Sigel E. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of risperidone for the treatment of adolescents and young adults with anorexia nervosa: a pilot study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;50:915.

Steinglass JE, Kaplan SC, Liu Y. The (lack of) effect of alprazolam on eating behavior in anorexia nervosa: a preliminary report. Int J Eat Disord. 2014;47:901.

Walsh BT, Kaplan AS, Attia E. Fluoxetine after weight restoration in anorexia nervosa: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295:2605.

Ragguett R, Hahn M, Messina G, Chieffi S, Monda M, De-Luca V. Association between antipsychotic treatment and leptin levels across multiple psychiatric populations: an updated meta-analysis. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2017;32:6.

Stip E, Lungu OV. Salience network and olanzapine in schizophrenia: implications for treatment in anorexia nervosa. Can J Psychiatr. 2015 Mar;60(3 Suppl 2):S35–9.

McFadden KL, Tregellas JR, Shott ME, Frank GK. Reduced salience and default mode network activity in women with anorexia nervosa. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2014;39(3):178–88.

Oberndorfer TA, Frank GK, Simmons AN, Wagner A, McCurdy D, Fudge JL, Yang TT, Paulus MP, Kaye WH. Altered insula response to sweet taste processing after recovery from anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(10):1143–51.

Palaniyappan L, White TP, Liddle PF. The concept of salience network dysfunction in schizophrenia: from neuroimaging observations to therapeutic opportunities. Curr Top Med Chem. 2012;12(21):2324–38.

Palaniyappan L, Liddle PF. Does the salience network play a cardinal role in psychosis? An emerging hypothesis of insular dysfunction. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2012;37(1):17–27.

Stip E, Lungu OV, Anselmo K, et al. Neural changes associated with appetite information processing in schizophrenic patients after 16 weeks of olanzapine treatment. Transl Psychiatry. 2012;2(6):e128.

Leung M, Cheung C, Yu K, et al. Gray matter in first-episode schizophrenia before and after antipsychotic drug treatment. Anatomical likelihood estimation meta-analyses with sample size weighting. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37(1):199–211.

Funding

The authors declared no financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.Ç.: Literature search and review, preparation of the manuscript, statistical analysis. S.Ç.: Literature search and review, preparation of the manuscript, statistical analysis. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Approval from the Ethics Committee of Arel University has been obtained.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Çöpür, S., Çöpür, M. Olanzapine in the treatment of anorexia nervosa: a systematic review. Egypt J Neurol Psychiatry Neurosurg 56, 60 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41983-020-00195-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41983-020-00195-y