Abstract

Background

Cowpea seed beetle, Callosobruchus maculatus (L.) (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae: Bruchinae), is the most important pest of stored cowpea in tropical regions. This study was designed to determine the presence of parasitoids associated with C. maculatus, investigate the efficacy of the parasitic wasp, Dinarmus basalis Rondani (Hymenoptera: Pteromalidae), in controlling C. maculatus as influenced by time and number of applications and ascertain the use of olfactory cues by D. basalis in host searching. Three markets in Ibadan, Southwest Nigeria, namely: Bodija, Mapo and Ojoo, were purposively surveyed for parasitoids associated with C. maculatus. Two pairs of D. basalis were released at 3-day intervals into cowpea seeds previously infested with C. maculatus. Treatments included: four times of parasitoid applications (4-TPA), three applications (3-TPA), two applications (2-TPA), 1 application (1-TPA) and a control without parasitoid application (0-TPA). All treatments were replicated four times in a completely randomized design to determine F1 progeny of C. maculatus and seed damage. Olfactory bioassay was carried out with D. basalis adults placed in a Y-tube olfactometer; and their preference for infested or uninfested three cowpea varieties, namely: Ife Brown, Ife BPC (Branching Peduncle) and Oloyin, as well as infested cowpea grains or pure air was evaluated.

Results

Among the previously known parasitoids associated with C. maculatus, only D. basalis was found in the sampled markets. F1 progeny of adult C. maculatus reduced from 4.75 individuals (0-TPA) to 1.25 (2-TPA), 0.25 (3-TPA) and 0 (4-TPA). Concurrently, the number of exit holes on cowpea seeds significantly (p < 0.05) ranged from 5.25 (0-TPA) > 3.21 (1-TPA) > 2.20 (2-TPA) > 2.18 (4-RAP) > 1.39 (3-TPA). Adults D. basalis were more attracted to infested grains of Ife Brown (χ2 = 4, df = 1, p = 0.0455) and infested grains of Ife BPC (χ2 = 4, df = 1, p = 0.0455) than clean air. Similarly, adults D. basalis were more attracted to infested Ife Brown than the uninfested (χ2 = 5, df = 1, p = 0.0254). The results further showed that there were non-significant differences between the infested and uninfested grains of Ife BPC (χ2 = 0.2, df = 1, p = 0.6547) and Oloyin (χ2 = 3.2, df = 1, p = 0.0736) varieties.

Conclusions

Adult D. basalis reduced emergence of C maculatus and reduced damage in cowpea seeds. Olfactory cues played a necessary role in host-searching efforts of D. basalis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Cowpea (Vigna unguiculata (L) Walp.) is an annual herbaceous plant in the family Fabaceae (Muranaka et al. 2016). It is a major staple food crop, supplying the much needed protein in sub-Saharan Africa (Dugje et al. 2009). Kamara et al. (2018) noted that over 12.61 million ha are grown to cowpea worldwide and Nigeria is the largest cowpea producer accounting for over 2.5 million tons of grain production from an estimated 4.9 million hectares. It has been identified as an essential component of cropping systems in the sub-humid tropics (DaSilva et al. 2018) due to its ability to fix atmospheric nitrogen: enriching soils where it is planted and limiting the need for fertilizer application. In comparison with other crops, cowpea is well adapted to high temperature and resistant to drought stress (Hall 2004).

Many pest insects attack cowpea plants at various stages of the crop’s life cycle. Boukar et al. (2011) recorded that some notable pests of cowpea including: Aphids: Aphis craccivora Koch. (Hemiptera: Aphididae), Megalurothrips sjostedti (Trybom) (Thysanoptera: Thripidae), the legume pod borer, Maruca vitrata Fabricius (Lepidoptera: Crambidae), a complex of pod-sucking bugs (e.g., Clavigralla tomentosicollis Stäl and Riptortus dentipes Fabricius) and the chrysomelid, Callosobruchus maculatus (Fabricius)), feed on cowpea and reduce its production potential. The chrysomelid, C. maculatus (Fabricius), is a field-to-store pest of cowpea, which lays its eggs on mature cowpea pods and emerges in farm stores and warehouses, causing up to 90% damage on stored cowpea grains (Ekeh et al. 2013). It is a cosmopolitan pest species, which originated in Africa, but has spread to tropical and sub-tropical parts of the world (Beck and Blumer 2014). Cowpea seeds infested with C. maculatus have reduced market value, quality and viability (Akinbuluma and Adeyemi 2017).

Misuse of synthetic chemicals is a common practice leading to a build-up of the toxic chemicals in the environment and pest resurgence in some cases (Omoloye 2009). The use of biopesticides is not widely accepted among farmers, and it takes time to develop improved crop varieties with high yield, quality and multiple disease resistance (Vales et al. 2014). As a result of these challenges, alternative methods of pest management are continuously being sought. Biological control using parasitoids has been proposed as an alternative option in the management of C. maculatus. Some hymenopteran ectoparasitoids such as Uscana lariophaga (Steffan), Dinarmus basalis (Rondani) and Eupelmus vuilleti (Crawford) are among the promising biocontrol agents for C. maculatus (Sanon et al. 1998). The pteromalid, D. basalis Rondani (Hymenoptera, Pteromalidae), is a larvaphagous ectoparasitoid, usually present in cowpea fields and stores (Sanon et al. 2005). It is effective in controlling populations of C. maculatus and C. chinensis in the West African countries of Benin, Burkina Faso, Niger and Nigeria (Iloba et al. 2007). Ketoh et al. (2005) reported high mortality of C. maculatus due to the release of D. basalis, although mortality was higher when essential oil extracted from Cymbopogon schoenanthus was combined with the ectoparasitoid. Along with its sympatric species, Eupelmus vuilleti Crawford and E. orientalis Crawford (Hymenoptera: Eupelmidae), D. basalis parasitize the immature stages of C. maculatus (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) and Bruchidius atrolineatus (Coleoptera: Bruchidae) which develop inside the seeds of the cowpea (Rojas-Rousse 2010). A survey of the hymenoptera population showed that E. orientalis was the most abundant species at the beginning of storage with a significant population decrease within 2 months of storage. However, D. basalis and E. vuilleti coexisted for several months in these structures which form uniform and relatively closed habitats, resulting in inter- and/or intraspecific competition (Rojas-Rousse 2010).

Although D. basalis is the biological control agent of choice in this study, there is no recent study to confirm the association of the parasitoids with C. maculatus in Ibadan, Nigeria. Time of applications and number of parasitoids may constitute some essential factors that determine the success or failure of a biological control program in storage system (Tazerouni et al. 2019), but information is scanty on the number and time of application of D. basalis that could most effectively manage C. maculatus populations. As well, chemical communication is important in behavioral adaptation and survival of insects; specific chemical messages are transmitted between insects and their plant hosts through substances known as semiochemicals (Abd El-Ghany 2020).

Ayasse et al (2001) reported that hymenopterans are probably the most biologically diverse insect order in existence and they employ numerous sensory modalities in their communication, and host-finding strategies in wasps are reportedly achieved by using host-derived chemicals (Adams et al. 2020). Predators and parasitoids are sometimes attracted by herbivore-induced plant volatiles released as a result of the activities of their hosts/preys (Takabayashi and Shiojiri 2019). Earlier reports also showed that the plant seeds in which the parasitoids’ host develops usually influence their biology and behavior (Seagraves 2009). Thus, the success of the D. basalis in the host search depends on its response to the chemical cues coming from the host and the host plant (Sankara et al. 2014). Since the immature stages of C. maculatus are generally internal feeders, it is not practicable to study the exact responses by D. basalis, but the female behavior of D. basalis was studied through olfactory response to odors released by infested and uninfested cowpea seeds as well as to clean air.

Therefore, the objectives of this study were to: (a) determine the presence of parasitoids associated with C. maculatus in three major markets in Ibadan, (b) investigate how number and time of release affect the efficiency of D. basalis in controlling populations of C. maculatus and (c) ascertain whether olfactory stimulus is possibly, a host-searching mechanisms adopted by D. basalis.

Methods

Location and experimental condition

All experiments were carried out at the Entomology Research Laboratory and Insect Chemical Ecology Laboratory of the Department of Crop Protection and Environmental Biology (CPEB), University of Ibadan, Oyo State, with temperature and relative humidity of 28 ± 2 °C and 67 ± 3%, respectively.

Insect culture

Cowpea seeds infested with C. maculatus were obtained from grain sellers in Mapo market, Ibadan. The parasitoid, D. basalis was found associated with cowpea seeds bearing eggs of C. maculatus. Identification of the parasitoid was done at the Insect Reference Collection and Identification Services Centre in the Department of CPEB, Ibadan, Nigeria. Identification was done by Dr. M. D. Akinbuluma, assisted by the technicians. This was achieved by following the database of the collections. The pteromalid, D. basalis, was identified under the family Pteromalidae with reference: 003 in the insect box and features confirmed using a dichotomous key. Adult C. maculatus were placed in Kilner jars containing clean cowpea seeds to raise culture, while D. basalis culture was raised on cowpea seeds infested with C. maculatus. Teneral adults of the beetle and pteromalids were used for the experiments.

Collection and preparation of seeds

Three cowpea varieties, namely: Ife Brown, Ife BPC (Branching Peduncle) and Oloyin, were used in the study. Seeds of Ife Brown and Ife BPC were obtained from the Institute of Agricultural Research and Training (IAR&T), Moor Plantation, Ibadan, while Oloyin seeds were sourced from a local grain seller in Bodija Market, Ibadan.

Survey for parasitoids associated with Callosobruchus maculatus

Three prominent markets, namely: Bodija (lat. 7.433188°; lon. 3.913583°), Mapo (lat. 7.376453°; lon. 3.895422°) and Ojoo (lat. 7.467611°; lon. 3.912552°), were purposively surveyed to determine the presence of parasitoids. Survey was conducted on a monthly basis over a period of 5 months from January to May 2021. At every instance, samples containing cowpea pods, seeds (broken and intact) and insects were obtained. Cowpea grains from each market were bulked, and 100 g of grains was weighed into each of three 1-L Kilner jars. Samples were covered and left in the laboratory for emergence of C. maculatus and any associated parasitoids.

Efficiency of Dinarmus basalis in controlling populations of Callosobruchus maculatus

Three pairs (1:1) of adult C. maculatus were released into Petri dishes containing 20 g of cowpea seeds (Ife Brown). A hole was made on the lid of each Petri dish to allow respiration of the insects but covered with a net to prevent the insects from escaping. The beetles were left undisturbed for 7 days to allow them mate and oviposit and thereafter removed. Two pairs of D. basalis adults were then released into all but one treatment (Treatment E), which served as the control, following a 3-day interval, with one treatment being exempted at each parasitoid application. Consequently, the treatments were as follows:

-

Treatment A—received four sets of D. basalis (4 times of parasitoid applications (4-TPA)

-

Treatment B—received three sets of D. basalis (3-TPA)

-

Treatment C—received two sets of D. basalis (2-TPA)

-

Treatment D—received one set of D. basalis (1-TPA)

-

Treatment E—received no D. basalis (0-TPA)

Treatments were arranged in a completely randomized design (CRD) with four replications. Adults D. basalis were removed from all treatments, 18 days after initial C. maculatus infestation. Cowpea seeds in the Petri dishes were left until the emergence of F1 progeny of both C. maculatus and D. basalis. Emerged adult insects were counted and recorded at a 4-day interval for 4 weeks until no further emergence was observed, and thereafter, cowpea seeds were visually observed for exit holes as evidence of damage.

Olfactory bioassay

This experiment was carried out in a Y-tube olfactometer to evaluate: (a) response of female D. basalis adults to odors from infested and clean air and (b) response of female D. basalis adults to infested cowpea grains and uninfested cowpea grains. Here, infested cowpea grains refer to grains bearing eggs of C. maculatus adults, while uninfested grains refer to clean and intact cowpea seeds, free from any form of damage. Twenty infested cowpea grains from each of the three varieties were separately placed in a polyethylene bag, and another polythene bag was filled with clean air. Compressed clean air from a pump was drawn through two flow meters at a rate of 60 mL/min and then passed through the polyethylene bags containing the odor source and the clean air. The arms of the Y-tube were connected to each odor source using Teflon tubes. Sixteen adult female D. basalis (in four batches) were individually introduced to the stem inlet of the tube and observed for 5 min.

In another setup, 20 infested and 20 uninfested cowpea grains from the three varieties were placed in two separate polyethylene bags and compressed clean air from a pump was drawn through two flow meters at a rate of 60 mL/min. Twenty adult female D. basalis were individually introduced to the stem inlet of the tube and observed for 5 min. Preference of D. basalis to infested or uninfested cowpea varieties and to infested cowpea varieties or clean air was determined.

Statistical analysis

Data obtained on number of F1 progeny of C. maculatus and D. basalis were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Data on cowpea seed damage were square root transformed prior to ANOVA with DSAASTAT (2012 version). Preference of D. basalis to infested or uninfested cowpea varieties and to infested cowpea varieties or clean air was compared using Chi-square (χ2) test. Means were separated using Fisher’s least significant difference (LSD) at 5% level of significance.

Results

F1 progeny of Callosobruchus maculatus, Dinarmus basalis and cowpea seed damage

The highest number of F1 progeny of C. maculatus (4.75 individuals) was observed in the treatment with no D. basalis application, and this was significantly different (p < 0.05) from treatments that received one, three and four applications. There was no emergence of F1 progeny of C. maculatus on the treatments that received the highest number of D. basalis (Table 1). The results also showed the corresponding numbers of adults D. basalis that emerged from each treatment. Treatments that received one and four applications had 14.75 and 9.25 adults D. basalis, respectively, and were significantly different (p < 0.05) from other treatments. The highest seed damage (number of holes) was recorded on cowpea seeds that did not receive D. basalis, which was significantly higher (p < 0.05) than other treatments (Table 1). Treatment that did not receive D. basalis had the highest (5.28 holes) significant number of exit holes.

Attraction of Dinarmus basalis to odors

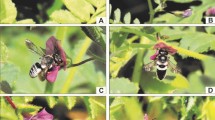

The attraction of adult female D. basalis to odors released from infested and clean air as well as infested and uninfested grains of three cowpea varieties is presented in Fig. 1. Adults D. basalis were more attracted to infested grains of Ife Brown (χ2 = 4, df = 1, p = 0.0455) and infested grains of Ife BPC (χ2 = 4, df = 1, p = 0.0455) than clean air. There was non-significant difference (p < 0.05) in the attraction of D. basalis adults to infested grains of Oloyin when compared against clean air (χ2 = 0, df = 1, p = 1). Similarly, adult D. basalis were more attracted to infested Ife Brown than the uninfested (χ2 = 5, df = 1, p = 0.0254). The results further showed that there were non-significant differences between the infested and uninfested grains of Ife BPC (χ2 = 0.2, df = 1, p = 0.6547) and Oloyin ((χ2 = 3.2, df = 1, p = 0.0736) varieties (Fig. 1).

Discussion

The results from the survey confirmed that parasitoids occurred alongside their hosts in the markets in Ibadan, Nigeria. Among the known parasitoids associated with C. maculatus, the fact that only D. basalis was found during the survey may be attributed to its distinct host-searching ability (Sanon et al. 1998) and its responsiveness to olfactory cues. Although earlier authors have reported a coexistence between D. basalis and Eupelmus vuilleti in storage structures which form uniform and relatively closed habitats, resulting in inter and/or intraspecific competition (Rojas-Rousse 2010), E. vuilleti was not found in the survey of this study.

The treatments that received four applications of D. basalis had the least number of emerged C. maculatus, showing that application of D. basalis was effective in suppressing populations of C. maculatus, under laboratory conditions. This result agrees with the report of Iloba et al. (2007), which stated that continuous application of D. basalis increased percentage mortality of C. maculatus from 25.52 to 99.48%. However, the results showed that there was a non-significant difference among the treatments that received D. basalis applications irrespective of the number of times application was made. This suggests that even a single application of D. basalis will inhibit the development of C. maculatus on cowpea seeds and the number of applications may only be increased to achieve better control.

Treatment that received only one application of D. basalis had the highest number of emerged D. basalis on all days where observation was made. This could be due to the fact that parasitoids in other treatments showed a reduction in its host-searching efficiency, leading to an even greater decrease in its fecundity. It is possible that coexisting parasitoids compete for a limited number of hosts (Pekas et al. 2016) or by a direct and antagonistic interaction with one another, limiting access to hosts (DeLong et al. 2011). The combined effects of individual host–parasitoid interaction may be nonlinear rather than additive because of indirect trophic effects or the modification of direct interactions (which may be inherently nonlinear) (Zhang et al. 2021). The control treatment that received no D. basalis had the highest number of C. maculatus emergence and corresponding highest seed damage (represented by adult emergent holes). This is in consonance with Akinbuluma and Adeyemi (2017) who remarked that when left without any form of control, C. maculatus populations will cause severe damage to cowpea seeds.

The results from the olfactory bioassay showed that D. basalis adults displayed a marked preference for infested cowpea seeds than uninfested seeds or pure air, suggesting that D. basalis was responsive to volatiles released by the activity of its host on cowpea seeds. This is corroborative of a report by Sankara et al. (2014) who concluded that D. basalis was attracted to odors released from cowpea seeds infested by C. maculatus. The preference of female D. basalis for seed odors compared to pure air could be explained by the fact that the prolonged development of D. basalis within seed complexes increased their sensitivity to the complexes’ odors. Once emitted, the odors of seed complexes may attract females and stimulate their locomotive activity (Sankara et al. 2014). Watching et al. (2020) in their study of characterizing odors released by C. maculatus noted that D. basalis females were more attracted to fourth instar larvae of C. maculatus than other larval instars, while Kumazaki et al. (2000) observed that D. basalis utilizes the oviposition-marking pheromone of Callosobruchus species as a host-recognizing kairomones of their host.

Conclusions

In order to achieve management of C. maculatus, timely application of the parasitoid, D. basalis, was critical. This process was observed to be mediated by olfactory response of D. basalis to C. maculatus-infested cowpea seeds. Further studies of the mechanism involved in the chemical communication of the insect species are highly recommended with a higher number of insect population.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of variance

- CRD:

-

Completely randomized design

- BPC:

-

Branching Peduncle

- TPA:

-

Times of parasitoid application

References

Abd El-Ghany NM (2020) Pheromones and chemical communication in insects. In: Dimitrios K, Anna K, Kassio FM (eds) Pests, weeds and diseases in agricultural crop and animal husbandry production. Intech Open. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.92384

Adams RMM, Wells RL, Yanoviak SP, Frost CJ, Fox EGP (2020) Interspecific eavesdropping on ant chemical communication. Front Ecol Evol 8:24. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2020.00024

Akinbuluma MD, Adeyemi WA (2017) Laboratory evaluation of Cedrela odorata (L.) for the management of Callosobruchus maculatus (F.) in Ibadan, Nigeria. Nig J Ecol 16:120–127

Ayasse M, Paxton RJ, Tengo J (2001) Mating behavior and chemical communication in the order hymenoptera. Annu Rev Entomol 46:31–78

Beck CW, Blumer LS (2014) A handbook on bean beetles, Callosobruchus maculatus

Boukar O, Massawe F, Muranaka S, Franco J, Maziya-Dixon B, Singh B, Fatokun C (2011) Evaluation of cowpea germplasm lines for protein and mineral concentrations in grains. Plant Genet Res 9:515–522

Da Silva AC, da Costa SD, Junior TDL, da Silva PB, dos Santos CR, Siviero A (2018) Cowpea: a strategic legume for food security and health in legume seed nutraceutical research. IntechOpen, pp 47–65. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.79006

DeLong JP, Vasseur DA (2011) Mutual interference is common and mostly intermediate in magnitude. BMC Ecol 11:1

Dugje IY, Omoigui LO, Ekeleme F, Kamara AY, Ajeigbe H (2009) Farmers’ guide to cowpea production in West Africa. IITA, Ibadan

Ekeh FN, Onah IE, Atama CI, Ivoke N, Eyo JE (2013) Effectiveness of botanical powders against Callosobruchus maculatus (Coleoptera: Bruchidae) in some stored leguminous grains under laboratory conditions. Afr J Biotechnol 12(12):1384–1391

Hall AE (2004) Breeding for adaptation to drought and heat in cowpea. Eur J Agron 21(4):447–454

Iloba BN, Umoetok SBA, Keita S (2007) The biological control of Callosobruchus maculatus Fabricius by Dinarmus basalis Rondani on stored cowpea (Vigna unguiculata) seeds. Res J Appl Sci 2(4):397–399

Kamara AY, Omoigui LO, Kamai N, Ewansiha SU, Ajeigbe HA (2018) Improving cultivation of cowpea in West Africa. In: Sivasankar S, Bergvinson D, Gaur P, Kumar S, Beebe S, Tamo M (eds) Achieving sustainable cultivation of grain legumes. Improving cultivation of particular grain legumes, Burleigh dodds series in agricultural science, vol 2. Burleigh Dodds Science Publishing, pp 1–18

Ketoh GK, Koumaglo HK, Glitho IA (2005) Inhibition of Callosobruchus maculatus (F.) (Coleoptera: Bruchidae) development with essential oil extracted from Cymbopogon schoenanthus L. Spreng (Poaceae), and the wasp Dinarmus basalis (Rondani) (Hymenoptera: Pteromalidae). J Stored Prod Res 41:363–371

Kumazaki M, Matsuyama S, Suzuki T, Kuwahara Y, Fujii K (2000) Parasitic wasp, Dinarmus basalis, utilizes oviposition-marking pheromone of host azuki bean weevils as host-recognizing kairomone. J Chem Ecol 26(12):2677–2695. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026425407150

Muranaka S, Shono M, Myoda T, Takeuchi J, Franco J, Nakazawa Y, Boukai O, Takagi H (2016) Genetic diversity of physical, nutritional and functional properties of cowpea grain and relationships among the traits. Plant Genet Res 14:67–76

Omoloye AA (2009) Ecological basis of pest management in fundamentals of insect pest management. Ibadan

Pekas A, Tena A, Harvey JA, Garcia-Marí F, Frago E (2016) Host size and spatiotemporal patterns mediate the coexistence of specialist parasitoids. Ecol 97:1345–1356

Rojas-Rousse D (2010) Facultative hyperparasitism: extreme survival behavior of the primary solitary ectoparasitoid, Dinarmus Basalis. J Insect Sci 10:101

Sankara F, Dabiré LCB, Ilboudo Z, Dugravot S, Cortesero AM, Sanon A (2014) Influence of host origin on host choice of the parasitoid Dinarmus basalis: does upbringing influence choices later in life? J Insect Sci 14(26):1–11

Sanon A, Ouedraogo AP, Tricault Y, Credland PE, Huignard J (1998) Biological control of bruchids in cowpea stores by release of Dinarmus basalis (Hymenoptera: Pteromalidae) adults. Environ Entomol 27:717–725

Sanon A, Dabiré C, Ouedragogo AP, Huignard J (2005) Field occurrence of bruchid pests of cowpea and associated parasitoids in a sub-humid zone of Burkina Faso: importance on the infestation on two cowpea varieties at harvest. Plant Pathol J 4(1):14–20

Seagraves MP (2009) Ladybeetle oviposition behavior in response to the trophic environment. Biol Control 51:313–322

Takabayashi J, Shiojiri K (2019) Multi-functionality of herbivore induced plant volatiles in chemical communication in tritrophic interactions. Curr Opin Insect Sci 32:110–117

Tazerounib Z, Talebi AA, Rezaei M (2019) Functional response of parasitoids: its impact on biological control. In: Donnelly E (ed) Parasitoids: biology, behavior and ecology. Nova Science Publishers Inc

Vales MI, Ranga Rao GV, Sudini H, Patil SB, Murdock LL (2014) Effective and economic storage of pigeon pea in triple layer plastic bags. J Stored Prod Res 58:29–38

Watching D, Tamgno BR, NkenmogneKamdem IE, Zilbinkaye M, NgamoTinkeu LS, Ngassoum MB (2020) Volatile organic compounds as markers for detection of Callosobruchus maculatus (Fabricius) (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae), major pest of Bambara groundnut [Vigna subterranea (Linnaeus), Fabaceae] by the hymenopteran parasitoids. J Entomol Zool Stud 8(2):1441–1447

Zhang YZ, Jin Z, Miksanek JR, Tuda M (2021) Impact of a nonnative parasitoid species on intraspecifc interference and offspring sex ratio. Sci Rep 11:23215. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-02713-1

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Dr. Olajumoke Y. Alabi of the Department of Crop Protection & Environmental Biology for providing some equipment for this work and to Mrs Modupe Timothy for assisting in Y-tube olfactometry setup.

Funding

There was no funding received for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MDA conceptualized the idea. OPC conducted the experiments under the supervision of MDA. Both MDA and OPC analyzed, interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Akinbuluma, M.D., Chinaka, O.P. Efficacy of the parasitic wasp, Dinarmus basalis Rondani (Hymenoptera: Pteromalidae), in reducing infestations by the cowpea beetle, Callosobruchus maculatus (L.) (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae: Bruchinae). Egypt J Biol Pest Control 33, 43 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41938-023-00692-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41938-023-00692-1