Abstract

Wheat aphid, Sitobion avenae (Fab.), is a serious pest of wheat crop across the world. The present study was conducted to evaluate the potentials of the water plant extracts of Azadirachta indica (neem) or Eucalyptus camaldulensis and the entomopathogenic fungi (EPF); Beauveria bassiana or Metarhizium anisopliae against the aphid species. After 5 days of applications, the combined mixture of B. bassiana and eucalyptus extract caused the maximum mortality rate (87%). While the combination of B. bassiana with neem extract showed the least rate (54%). Fecundity was negatively affected by the single and combined treatments of EPF and botanicals extracts. The lowest fecundity (7 nymphs per female) was recorded when the aphid was treated by the binary mixture of B. bassiana and eucalyptus extract. Correspondent maximum fecundity (29 nymphs per female) in 5 days was recorded in control treatment, while 23 nymphs were produced by a single female when treated with the binary mixture of B. bassiana and neem extract. The results indicated that EPF and botanical extracts (neem or eucalyptus) caused significant reduction in survival and fecundity of S. avenae. Therefore, they may be used as promising natural alternatives to synthetic insecticides against the wheat aphid species.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Wheat crop, Triticum aestivum L., the most widely grown cereal in the world, is one of the major staple crops (foods) throughout the world, including Pakistan, by serving food to more than 35% of the world population (Khan et al. 2013). Wheat aphid, Sitobion avenae (Fab.) (Hemiptera: Aphididae), is one of the major insect pests of wheat worldwide. This species causes serious yield losses by direct feeding and indirectly by spreading wheat pathogens during early stages of wheat crop (Kindler et al. 1995). Several species of aphids have become resistant due to excessive use of insecticide. Thus, it is required to control their populations effectively (Shah et al. 2017).

Under changing the food safety standards, biopesticides, based on entomopathogens and botanicals, can be the best replacements for synthetic chemicals.

Entomopathogenic fungi (EPF) are one of the important entomopathogens of insect pests. Among the EPF, Beauveria bassiana is used widely because of its virulence against different insect pests. It naturally grows in soils and acts as a parasite causing the white muscardine disease in various arthropod species (Barbarin et al. 2012). Another fungus species, Metarhizium anisopliae is also an important EPF that causes the green muscardine disease in insects. It is broadly used for the biological control of many insect pest species (Reddy et al. 2014).

Some botanicals possess an insecticidal activity. They are generally less harmful to the environment, and their use avoids the development of insect resistance (Isman 2006). They are used as direct spray, soil amendments for plant parts, intercropping with main crop, grain protectants, and also as synergists (Prakash et al. 2008). There are many products that are safe as well as cost-effective that is why botanicals are considered extra efficient. For pest management, botanicals can be an attractive alternates to synthetic chemical insecticides because they pose little threat to human (Isman 2006). Azadirachta indica (neem) is a well-known plant species used for its insecticidal activity (Cruz-Estrada et al. 2013). It produces limonoid extracts with various insecticidal activities against more than 250 species of agricultural imporatnce (Morgan 2009). Additionally, it is known to show synergistic ability with some chemical or biological insecticides (Mohan et al. 2007). Eucalyptus leaves contain many terpenoid compounds like α- and β-pinene, 1,8-cineole (CIN), terpineol, and globulol (Lucia et al. 2012). These compounds have been described to have antimicrobial, antiviral, insecticidal, and antifungal activities, and even have been confirmed for contact and fumigant insecticidal action against some stored grain and other insect pests (Mann and Kaufman 2012).

The compatibility between EPFs and pesticides may ease the selection of appropriate products under IPM programs (Neves et al. 2001). Such combined applications can improve the efficacy of control by reducing the applied amounts, minimizing environmental pollution threats and build-up of pest resistance (Usha et al. 2014). So, it is important to find some natural antagonists to be combined with EPFs, as many of the synthetic insecticides do not have compatibility with them (Neves et al. 2001).

This study was conducted to evaluate the synergetic effect of EPF; B. bassiana and M. anisopliae with two botanical extracts (Azadirachta indica and Eucalyptus camaldulensis) against wheat aphid species (Sitobion avenae) under laboratory conditions.

Materials and methods

The study was conducted at Entomological Laboratory of University College of Agriculture and Environmental Sciences, The Islamia University of Bahawalpur, Pakistan.

Insect collection and rearing

Wheat aphid species was collected from insecticide-free wheat fields of the university research area and reared on wheat seedlings grown in plastic pots (15 cm diameter, filled with sandy loam soil and organic matter (2:1), under laboratory conditions (24 ± 1 °C, 65 ± 10% RH), covered with aerial jars. The aphids were allowed to produce nymphs for further generation to get homogenous population (free of insecticidal pressure). From the next generation aphids, second and third nymphal instars were collected to be used in bioassay studies.

Preparation of plant extracts

The fresh leaves of neem, Azadirachta indica L. and Eucalyptus, Eucalyptus camaldulensis D. were collected and washed sufficiently by distilled water. After drying under shade, the leaves were grinded to fine powder with an electrical grinder. 10 g of plant powder was placed in conical flasks (250 ml) along with 100 ml of distilled water and placed on heating (60 °C) and shaked with magnetic stirrer (AM4, Velp Scientifica, Italy) for 6 h to dissolve the leaf powder properly. The solid residues were removed using muslin cloths, and plant extracts were then filtered (Whatman No. 1). After evaporation by using rotary evaporator (HB Digital, Heidolph, Germany) at 60 °C under vacuum, the dried plant extracts were brought to constant volume, using a hot air oven (60 °C) (Ali et al. 2017). These extracts were stored under 4 °C till used as a stock solution. Seven percent concentration of neem and eucalyptus leaf extracts was prepared by dilution with distilled water from this stock solution for experimental evaluation.

Preparation of concentration of entomopathogenic fungi

B. bassiana (RACER™) and M. anisopliae (PACER) were procured from Agri Life Ltd., India, which are formulated at CFU count of 108 fungal spores/g. The concentrations of 106 spores/ml of EPF were obtained by dissolving 1 g EPF formulations in 100 ml of water to apply on the aphids (Agri Life Ltd., India).

Bioassay

Ten S. avenae nymphs (second and third instars) were placed into Petri dish (9 cm diameter) and allowed to set on rooted wheat seedlings (roots covered with wet cotton plugs to keep the seedling alive). After they settled, botanicals extract and EPF were applied with the abovementioned concentrations, using a fine hand sprayer machine (Flip & Spray™ Bottles, Thomas Scientific, USA) with two shower shots to properly cover the Petri dish area. The treatments were set as follows:

T1 water (control); T2 (B. bassiana); T3 (M. anisopliae); T4 (neem extracts; T5 (eucalyptus extracts; T6 (B. bassiana + neem extract); T7 (B. bassiana + eucalyptus extract); T8 (M. anisopliae + neem extract); T9 (M. anisopliae + eucalyptus extract). The concentrations of EPF and botanicals were halved in combination treatments as 1:1. The bioassays were performed under the laboratory conditions at (24 ± 1 °C, 65 ± 10% RH). All treatments were triplicated. To evaluate the fecundity of mature aphids, fourth instar nymphs were treated by botanicals and EPF with the same way, and survived adults were shifted into new Petri dishes with fresh wheat seedlings to give F1 ones.

Data analysis

The aphid mortality rate was recorded on a daily basis. The fecundity data was recorded for 10 aphids from each treatment on a daily basis for 5 days after they started to give young ones. Evaluation of the tested materials and techniques was based on the mortality percentage and corrected by Abbot’s formula (Abbott 1925).

Where n = insect population, T = treated, and Co = control.

The mortality and fecundity data were subjected to factorial analysis of variance (ANOVA), using Minitab 16.1 software. The means were compared by applying Tukey’s HSD test at 5% level of significance to evaluate the impact of treatments on mortality and fecundity of treated wheat aphids.

Results and discussion

Effect of botanicals and entomopathogenic fungi on mortality rate of the wheat aphid

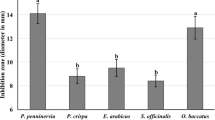

The botanicals and EPF showed remarkable potentials by causing significantly higher mortality rates within 48 h as compared to control treatment and resulted almost to (50%) reduction among treated wheat aphid individuals (F = 8.18, df = 8, and P < 0.001). Eucalyptus extract showed significantly (F = 10.89, df = 8, and P < 0.001) the highest mortality rate (36%) after 24 h, while the lowest mortality rate (4%) was recorded in the control treatment. The rest of the treatments caused intermediate mortality rates among the treated aphids. More than half of the treated aphids were found dead after 48 h in T5 and T7, while in other treatments, the mortality rate was comparatively lower, but higher than the control treatment (Table 1). T2 and T3 also showed little mortality among treated aphids after 24 h. It is inferred that the incubation period to germinate spores varies from species to species and it also depends upon temperature. In certain studies, EPF showed substantial mortalities in aphids after 24 h (Vu et al. 2007 and Kim et al. 2013). After 5 days, total aphids mortality (corrected by using Abbot’s formula) indicated that the binary mixture of B. bassiana and eucalyptus extract caused the maximum mortality (87%). Neem and eucalyptus extract also gave a significantly higher (75%) mortality rate among the treated aphids, with respect to other treatments. The combination of B. bassiana with neem extract showed the minimum mortality rate (54%), while the other treatments imposed the intermediate rates by (70%) after 5 days of botanical and EFP applications (Fig. 1). The variations among corrected mortality percentages were significantly different at all the treatments (F = 2.94, df = 7, and P = 0.0171).

The present study showed the virulence of EPF (B. bassiana and M. anisopliae) and botanicals extracts (neem and eucalyptus) against the wheat aphid species (S. avenae). B. bassiana was significantly effective when applied singly or in combination with eucalyptus leaf extract. EPF, B. bassiana caused higher mortality rates among the treated wheat aphid due to mycosis, secreting specific hydrolytic enzyme such as proteinase, chitinase, and lipase. Hydrolytic enzyme acts as a cuticle degrading enzyme (Fang et al. 2005). Metarhizium had less efficacy compared to B. bassiana. However, it caused more than (60%) mortality at a single or a binary mixture treatment. Previously, B. bassiana and M. anisopliae showed deleterious effects to different aphid species (Kim et al. 2013 and Saleh et al. 2016). Neem and eucalyptus extracts also caused higher mortality rates in the wheat aphid, followed by B. bassiana. Fatalities caused by neem and eucalyptus are well documented showing that neem-based products and certain botanicals like eucalyptus had a good potential to minimize the populations of different aphid species by reducing their survival and fecundity with their physical and biological actions (Pavela et al. 2004; Patil and Chavan 2009; Nia et al. 2015 and Sharma et al. 2016). The richness of terpenoids, alkenes, alkanes, alkyl halides, and like compounds in these plant extracts might give deleterious fate to the treated aphids (Nia et al. 2015; and Sharma et al. 2016).

The highest mortality was recorded when B. bassiana was applied in combination with eucalyptus leaf extract. It was also dependent on the type of extraction and the concentration used. Eucalyptus leaf extract affects the nervous system of the nymphs, which results in higher mortality, when combined with B. bassiana, which has already penetrated into the wheat aphid (Russo et al. 2015). Eucalyptus extract possesses terpenoid compound, which can cause disturbance in digestion, growth inhabitation, affect maturation and reproductive ability by decreasing appetite in exposed insects leading to death (Russo et al. 2015). Oppositely, the application of B. bassiana with neem extract showed the lowest mortality rate and higher fecundity. This might be due to the neem leaf extract can cause inhibition effects on mycelial growth, conidiogenesis, and spore germination of B. bassiana (Castiglioni et al. 2003). The compatibility of plant extracts with B. bassiana might be due to inconsistent concentrations of phytoalexins, sulfurade, terpenoids, and triterpenoids compounds (Diepieri et al. 2005). The compatibility of EPF with botanicals also depends upon the qualitative and quantitative variations in secondary metabolites composition, which may have a negative impact on the entomopathogenic microorganisms (Ribeiro et al. 2012). It is also important that the genetic variability of fungal isolates may also produce varied grades of susceptibility or compatibility to different phytosanitary products (Mohan et al. 2007).

Effect of botanicals and entomopathogenic fungi on fecundity of wheat aphid

The control and the binary mixture of B. bassiana and neem extract showed the maximum fecundity (29 and 23 nymphs per female) in 5 days. Wheat aphid treated with neem and eucalyptus extract produced only (13 nymphs/female) during the same time. The lowest fecundity was recorded at B. bassiana and eucalyptus extract (binary mixture) treatment, when a single female could produce only (7 nymphs) in 5 days (Fig. 2). The binary mixtures of M. anisopliae with neem and eucalyptus extracts also showed substantial decrease in the fecundity after exposure to the botanicals and EPF. So, the females in control treatment possessed higher reproductive fitness than at all other treatments (F = 113.75, df = 8, and P < 0.001).

Fecundity is a critical aspect of insect population, which can be affected by entomopathogens and plant extracts as reflected in terms of lowered fecundity, when S. avenae exposed to them in the study although variations were observed under different treatments. Treated aphids reproduced at slower rate than untreated ones, except when they were exposed to neem and B. bassiana binary mixture. Neem and eucalyptus extracts negatively affected the longevity as well as fecundity of cotton aphids (Bayhan et al. 2006). Similarly, Pavela et al. (2004) reported the lowest fecundity in cabbage aphids after exposure to systemic neem extract. Citrus aphids also produced lowered number of nymphs after they were exposed to neem seed extracts (Tang et al. 2002). The negative effects of fungal infections on fecundity and egg fertility were also reported, using fungal species B. bassiana and M. anisopliae on Russian wheat aphid (Wang and Knudsen 1993).

Conclusion

In conclusion, the present study indicated that the binary mixtures or combinations of EPF and botanicals are specific in action. The control of wheat aphid (S. avenae) was benefitted by the applications of the binary mixtures of EPF and botanicals, but their efficacy depended upon the mixing components. However, more research is needed to fractionate and isolate the active ingredients responsible for the mortality of aphids and to test their hazards and compatibility for a better biological control of aphids.

References

Abbott WS (1925) A method of computing the effectiveness of an insecticide. J Econ Entomol 18:265–267

Ali S, Ullah MI, Arshad M, Iftikhar Y, Saqib M, Afzal M (2017) Effect of botanicals and synthetic insecticides on Pieris brassicae (L., 1758) (Lepidoptera: Pieridae). Turk J Entomol 41(3):275–284

Barbarin AM, Jenkins NE, Rajotte EG, Thomas MB (2012) A preliminary evaluation of the potential of Beauveria bassiana for bed bug control. J Invert Pathol 111:82–85

Bayhan SO, Bayhan E, Ulusoy MR (2006) Impact of neem and extracts of some plants on development and fecundity of Aphis Gossypii Glover (Homoptera: Aphididae). Bulgar J Agri Sci 12:781–787

Castiglioni E, Vendramin JD, Alves SB (2003) Compatibility between Beauveria bassiana and Metarhizium anisopliae with Nimkol-L in the control of Heterotermes tenuis. Man Integr Plagas Agroecol 69:38–44

Cruz-Estrada A, Gamboa-Angulo M, Borges-Argáez R, Ruiz-Sánchez E (2013) Insecticidal effects of plant extracts on immature whitefly Bemisia tabaci Genn. (Hemiptera: Aleyroideae). Electron J Biotechnol 16(1):6–6

Diepieri RA, Martinez SS, Menezes AO (2005) Compatibility of the fungus Beauveria Bassiana (Bals.) Vuill. (Deuteromycetes) with extracts of neem seeds and leaves and the emulsible oil. Neotrop Entomol 34(4):601–606

Fang W, Leng B, Xiao Y, Jin K, Ma J, Fan Y, Feng J, Yang X, Zhang Y, Pei Y (2005) Cloning of Beauveria bassiana chitinase gene Bbchit1 and its application to improve fungal strain virulence. Appl Environ Microbiol 71:363–370

Isman MB (2006) Botanical insecticides, deterrents, and repellents in modern agriculture and an increasingly regulated world. Annu Rev Entomol 51(1):45–66

Khan A, Khan AM, Tahir HM, Afzal M, Khaliq A, Khan SY, Raza I (2013) Effect of wheat cultivars on aphids and their predator populations. Af J Biotech 10:18399–18402

Kim JJ, Jeong G, Han JH, Lee S (2013) Biological control of aphid using fungal culture and culture filtrates of Beauveria bassiana. Mycobiology 41(4):221–224

Kindler SD, Greer LG, Springer TL (1995) Feeding behaviour of the Russian wheat aphid (Homoptera: Aphididae) on wheat and resistant and susceptible slender wheat grass. J Econ Entomol 85:2012–2016

Lucia A, Juan LW, Zerba EN, Harrand L, Marcó M, Masuh HM (2012) Validation of models to estimate the fumigant and larvicidal activity of eucalyptus essential oils against Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae). Parasitol Res 110(5):167–186

Mann RS, Kaufman PE (2012) Natural product pesticides: their development, delivery and use against insect vectors. Min Rev Org Chem 9:185–202

Mohan MC, Reddy NP, Devi UK, Kongara R, Sharma HC (2007) Growth and insect assays of Beauveria bassiana with neem to test their compatibility and synergism. Biocont Sci Technol 17(10):1059–1069

Morgan ED (2009) Azadirachtin, a scientific gold mine. Bioorg Med Chem 17:4096–4105

Neves PMOJ, Hirose E, Tchujo PT (2001) Compatibility of entomopathogenic fungi with neonicotinoid insecticides. Neotrop Entomol 30:263–268

Nia B, Frah N, Azoui I (2015) Insecticidal activity of three plants extracts against Myzus persicae (Sulzer, 1776) and their phytochemical screening. Acta agri Slov 105(2):261–267

Patil DS, Chavan NS (2009) Bioefficacy of some botanicals against the sugarcane woolly aphid, Ceratovacuna lanigera Zehnter. J Biopest 2(1):44–47

Pavela R, Barnet M, Kocourek F (2004) Effect of Azadirachtin applied systemically through roots of plants on the mortality, development and fecundity of the cabbage aphid (Brevicoryne brassicae). Phytoparasitica 32(3):286–294

Prakash A, Rao J, Nandagopal V (2008) Future of botanical pesticides in rice, wheat, pulses and vegetables pest management. J Biopest 1(2):154–169

Reddy GVP, Zhao Z, Humber RA (2014) Laboratory and field efficacy of entomopathogenic fungi for the management of the sweet potato weevil, Cylas formicarius (Coleoptera: Brentidae). J Invert Pathol 122:10–15

Ribeiro LP, Blume E, Bogorni PC, Dequech STB, Brand SC, Junges E (2012) Compatibility of Beauveria bassiana commercial isolate with botanical insecticides utilized in organic crops in southern Brazil. Biol Agri Hort: 28;4:223–240

Russo S, Cabrera N, Chludil H, Yaber-Grass M, Leicach H (2015) Insecticidal activity of young and mature leaves essential oil from Eucalyptus globulus Labill. Against Tribolium confusum Jacquelin du Val (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae). Chil J Agri Res 75(3):375–379

Saleh AA, Lashin GMA, Ali AAM (2016) Impact of Entomopathogenic Fungi Beauveria Bassiana and Isaria fumosorosea on cruciferous aphid Brevicoryne Brassicae L. Inter J Sci Engineer Res 7(9):727–732

Shah FM, Razaq M, Ali A, Han P, Chen J (2017) Comparative role of neem seed extract, moringa leaf extract and imidacloprid in the management of wheat aphids in relation to yield losses in Pakistan. PLoS One 12(9):e0184639

Sharma U, Chandel RPS, Sharma L (2016) Effect of botanicals on fertility parameters of Myzus persicae (Sulzer). The Ecoscan 10(1&2):29–31

Tang YQ, Weathersbee AA, Mayer RT (2002) Effect of neem seed extract on the brown citrus aphid (Homoptera: Aphididae) and its parasitoid Lysiphlebus testaceipes (Hymenoptera: Aphidiidae). Environ Entomol 31(1):172–176

Usha J, Babu MN, Padmaja V (2014) Detection of compatibilty of entomopathogenic fungus Beauveria bassiana (bals.) Vuill. With pesticides, fungicides and botanicals. Inter J Plant Ani. Environ Sci 4(2):613–624

Vu VH, Hong SI, Kim K (2007) Selection of Entomopathogenic Fungi for aphid control. J Biosci Bioeng 104(6):498–505

Wang ZG, Knudsen GR (1993) Effect of Beauveria bassiana (Fungi: Hyphomycetes) on fecundity of the Russian wheat aphid (Homoptera: Aphididae). Environ Entomol 22(4):874–878

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to lab technicians for assisting to carry out the study.

Funding

The study was conducted with the available laboratory resources without any aid from any funding agency.

Availability of data and materials

All data of the study have been presented in the manuscript, and high quality and grade materials were used in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors carried out all the experiments, including the bioassay tests, analytical part, and analysis of data, and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

This study does not contain any individual person’s data.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Ali, S., Farooqi, M.A., Sajjad, A. et al. Compatibility of entomopathogenic fungi and botanical extracts against the wheat aphid, Sitobion avenae (Fab.) (Hemiptera: Aphididae). Egypt J Biol Pest Control 28, 97 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41938-018-0101-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41938-018-0101-9