Abstract

Background

Biologics have demonstrated efficacy in PsA in randomized clinical trials. More evidence is needed on their effectiveness under real clinical practice conditions. The aim of the present work is to provide real-world evidence of the effectiveness of biologics for PsA in the daily clinical practice.

Methods

CHRONOS was a multicenter, non-interventional, cohort study conducted in 20 Italian hospital rheumatology clinics.

Results

399 patients were eligible (56.9% females, mean (SD) age: 52.4 (11.6) years). The mean (SD) duration of PsA and psoriasis was 7.2 (6.9) and 15.3 (12.2) years, respectively. The mean (SD) duration of the biologic treatment under analysis was 18.6 (6.5) months. The most frequently prescribed biologic was secukinumab (40.4%), followed by adalimumab (17.8%) and etanercept (16.5%). The proportion of overall responders according to EULAR DAS28 criteria was 71.8% (95% CI: 66.7–76.8%) out of 308 patients at 6 months and 68.0% (95% CI: 62.7–73.3%) out of 297 patients at 1 year. Overall, ACR20/50/70 responses at 6 months were 41.2% (80/194), 29.4% (57/194), 17.1% (34/199) and at 1-year were 34.9% (66/189), 26.7% (51/191), 18.4% (36/196), respectively. Secondary outcome measures improved rapidly already at 6 months: mean (SD) PASI, available for 87 patients, decreased from 3.2 (5.1) to 0.6 (1.3), the proportion of patients with dactylitis from 23.6% (35/148) to 3.5% (5/142) and those with enthesitis from 33.3% (49/147) to 9.0% (12/133).

Conclusions

The CHRONOS study provides real-world evidence of the effectiveness of biologics in PsA in the Italian rheumatological practice, confirming the efficacy reported in RCTs across various outcome measures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Psoriatic disease has been recognized as a systemic inflammatory disorder affecting the skin, the nails and the joints, and that can be complicated by systemic comorbidities [1, 2]. Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a seronegative spondyloarthropathy characterized by musculoskeletal signs and symptoms (arthritis, enthesitis, dactylitis, axial disease) with associated pain and tenderness in the involved sites [3, 4]. In the majority of patients, the skin symptoms of psoriasis develop first, followed by the arthritis; however, in 15% of cases, arthritis precedes the skin manifestations [5]. In Italy, PsA affects an estimated 0.3–1.0% of the general population [6]. Globally, it accounts for around 20% of referrals to the early arthritis clinic and its prevalence in patients with psoriasis is estimated around 30% (ranging from 18 to 42%, depending on geographic region) [7]. Early diagnosis is crucial to ensure optimal management and prevent long-term functional disability.

Improved understanding of the pathogenesis of PsA has led to the development of biologic medications and small molecules targeting specific cytokines and signaling pathways, which have shown to prevent disease progression and improve quality of life. Almost two decades ago, tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFis) were the first biologic disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) approved for the treatment of PsA and since then several new biologic agents have been developed, targeting interleukin (IL) 12/23, IL-23, and IL17 [5, 8, 9]. These biologic agents are recommended for the treatment of active moderate-severe PsA in adults with inadequate response to previous non-biologic DMARDs [10]. Currently, the biologic medications that have demonstrated efficacy in PsA in randomized clinical trials (RCTs), and have been commercialized in Italy, include TNFi, the IL12/23 inhibitor ustekinumab, the IL17A inhibitors secukinumab and ixekizumab [11,12,13,14,15,16]. However, more evidence is needed on the effectiveness of these agents under real clinical practice conditions. The present study was designed to provide real-world evidence (RWE) of the effectiveness of biologic treatments for PsA in the Italian real-life clinical practice.

Methods

Study design and participants

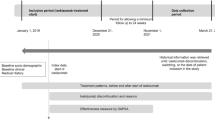

CHRONOS (EffeCtiveness of biologic treatments for psoriatic artHRitis in Italy: An ObservatioNal lOngitudinal Study of real-life clinical practice) was a multicenter, non-interventional study involving both retrospective and prospective data. The study was conducted in 20 Italian hospital rheumatology clinics. Patients were enrolled from September 2018 until September 2019 and data were collected until April 2020. Eligible patients satisfying inclusion criteria and not violating exclusion criteria were aged ≥ 18 years with diagnosis of PsA according to the treating rheumatologist, had initiated a biologic treatment more than 24 weeks and less than 24 months before enrolment visit (see Fig. 1) and had available data for DAS28 in the retrospective. Pregnant or breast-feeding women, receiving or having received biologic treatments as part of a clinical trial were excluded; treatment interruption before enrolment was not an exclusion criterion. Patients without available data of the clinical response at the start and at 6 months/1 year after treatment initiation were excluded from the evaluation of the primary objective.

Patient’s scheme. Each letter represents one patient, and each blue line represents a biologic therapy line; if the line ends with a circle, then the treatment line was interrupted, while if the line ends with an arrow, then the treatment line was not interrupted. All patients from “A” to “E” were eligible for the study because in all these cases at least one line of biological therapy for psoriatic arthritis was initiated at least 6 months before enrolment visit but no more than 24 months before enrolment visit; also patient “B” was eligible, even though he/she has interrupted the treatment line before enrollment. Regarding patients “A” and “C”, only the biologic therapy lines initiated within the retrospective period were considered (e.g. for patient “C”, only 2nd and 3rd line was evaluated). Patients with a red cross (i.e. “F”, “G” and “H”) were not eligible for the study because in all these cases every line of biological therapy for psoriatic arthritis was initiated less than 6 months before enrolment visit (patient “F”) or more than 24 months before enrolment visit (patients “G” and “H”). Patient “I” was eligible for the study because in this case at least one line of biological therapy for psoriatic arthritis was initiated at least 6 months but no more than 24 months before enrolment visit. Patient “J” was eligible too, but only the 2nd therapy line was considered (because the first therapy line did not start within the retrospective period)

Patients were withdrawn from the study in case of withdrawal of informed consent and privacy form, death, loss to follow-up, inclusion in a clinical trial involving treatment with biologic agents for PsA, or pregnancy. Stopping biologic treatment was not a reason for study exit.

At the enrolment visit, data since initiation of the earliest biologic were retrospectively collected from hospital medical charts or other clinical documents, while the minimum prospective observational period was 6 months (± 1 month), so that each patient was planned by design to have a total of observational period of at least 12 months except in case of early withdrawal (see Fig. 1). Patients who withdrew from the study were included in the analyses as long as they had available clinical outcomes.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome of the study was the proportion of patients with PsA achieving clinical response by the EULAR DAS28 response criteria [18] to the biologic therapy initiated in the retrospective period which started most recently with respect to enrolment (henceforth referred to as “biologic treatment under analysis”); response was evaluated at 6 months and 1 year after the baseline (start of biologic treatment under analysis).

DAS28 has been successfully used for PsA [18, 19] and is frequently adopted in the clinical practice in Italy [20, 21]; it takes into account a 28 tender joint count (range 0–28), a 28 swollen joint count (range 0–28), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) or C-reactive protein (CRP), and patients’ general health (GH) measured by a visual analogue scale [22]. As EULAR suggests that DAS28 calculation may be based on ESR (hereafter named DAS28 ESR) or on CRP (hereafter named DAS28 CRP), both measurements were calculated in our study.

Moreover, as sensitivity analysis, the proportion of patients achieving response at 6 months and 1 year after treatment initiation was calculated according to the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria, when available in the medical charts, in order to allow a comparison of the CHRONOS results with data from the literature. The ACR criteria have been widely used in clinical trials to measure the improvement induced by investigational treatments for rheumatoid arthritis and PsA [16, 23,24,25,26,27]. As they are not as commonly used in clinical practice in Italy, we did not select it as primary outcome. ACR20 responders should achieve a 20% improvement in tender or swollen joint counts as well as a 20% improvement in at least three out of the other five criteria (patient assessment, physician assessment, pain scale, disability/functional questionnaire, ESR or CRP). ACR50 and ACR70 follow similar patterns of definition.

The clinical response was evaluated also in terms of presence of dactylitis (number of patients with dactylitis and of affected fingers according to the judgment of the treating rheumatologist), enthesitis (presence and location evaluated by Leed Enthesitis Index, LEI), and presence of axial arthritis (according to the judgment of the treating rheumatologist) over the study observation period.

Secondary outcome measures were the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) score—ranging 0–72 and increasing with increasing severity—, the Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index (HAQ-DI)—ranging 0–3 and increasing with increasing disability [28]—, and the Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire for Medication-9 (TSQM-9) subscale scores—ranging from 0 to 100 with higher scores representing higher satisfaction [29, 30]. Switchers were defined as patients switching from a branded/biosimilar to a branded/biosimilar of another class (changes in dosage or frequency within the same therapy class were not considered as a switch); patients who discontinued stopped the biologic treatment under analysis before end of observation.

Sample size

Enrolling 400 patients with PsA, 15% of whom might not be evaluable for the primary analysis, was considered feasible and hence the achievable precision for 340 patients was calculated for the primary endpoint at 6 months and 1 year after initiation of the biologic treatment under analysis. Based on the existing literature [31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38], an expected proportion of patients achieving response between 38.0 and 57.8% at 6 months and between 42.0 and 53.0% at 1 year was considered. The achieved precision was evaluated in terms of relative error (i.e. the ratio between 95% CI half-width of the expected proportion and the expected proportion itself) and it was considered good because it was lower than 15%.

Statistical analysis

No formal statistical hypotheses were set. Descriptive analyses were performed; quantitative variables were described by mean, standard deviation, median, 25th and 75th percentile, minimum and maximum, while qualitative variables by absolute and relative frequency. Bilateral 95% confidence intervals were given where relevant.

Enrolled patients who did not meet the study criteria, were excluded from analyses. However, patients with follow-up visits performed outside the visit’s window defined by study protocol, were not excluded from analyses.

The patients with and without available response at 6 months and 1 year were compared in relation to the main patient characteristics at the start of biologic treatment (age, gender, ethnicity, duration of psoriasis and PsA, type of biologic treatment, number of prior biologic therapies and number of biologic therapies during the study) in order to evaluate possible selection bias and to better contextualize obtained results. T-test for normally distributed variables, non-parametric Wilcoxon Rank-Sum Test for non-normally distributed numerical variables and Chi-square or Fisher test for categorical variables were performed to compare patients with vs without available outcome measures.

The proportion of eligible patients discontinuing or switching was calculated and a Kaplan–Meier analysis was done in order to evaluate the persistence from the biologic treatment under analysis. The persistence was defined as months of treatment and the event was defined as discontinuation of the treatment or switch to another one. Dropped-out patients who did not have the event before discontinuation or patients who had no event at the end of observation period were censored at the date of the drop out or of the last available visit, respectively.

Site monitoring, data management, and statistical analysis were performed by MediNeos (Modena, Italy). Database management and data analysis were performed using SAS Enterprise Guide v. 7.1 and SAS 9.4.

Results

Patient population

A total of 409 patients were enrolled; among these, the eligible patients were 399 (97.6%) because 10 patients did not meet the inclusion criteria (3 patients had no diagnosis of PsA, 6 patients had no biological therapy for PsA initiated between 24 weeks and 24 months before enrolment and 1 patient had no available data for DAS28 in the retrospective period) (see Fig. 2). Seventeen patients (4.3% of the eligible) prematurely discontinued the study (11 were lost to follow-up, 2 became pregnant, 2 due to Covid-19 emergency, 1 died and 1 moved to another structure). Not all eligible patients were evaluable for the primary analysis on clinical response (based on DAS28) at the study time point; as 91 patients at 6 months and 102 patients at 1 year did not have available data on clinical response, 308 and 297 patients were evaluable at 6 months and 1 year, respectively (see Fig. 2).

Notable differences between patients with vs without available response were observed only in relation to the duration of PsA with a median (25th–75th percentile) time of 5.0 (2.1–10.8) years versus 3.5 (2.2–6.3) years in patients with vs without available response at 1 year, respectively (Wilcoxon Rank-Sum Test p-value = 0.03) and in the number of received biologic therapies during the study (85.5%, 9.8%, 4.0%, 0.7% of patients with available 1-year response vs. 67.6%, 27.5%, 3.9%, 1.0% of patients without available response received 1, 2, 3 or 4 biologics, respectively; Fisher exact Test p-value = 0.0002).

The mean observation period in all eligible patients was 20.3 months (SD 5.7). Of the 399 eligible patients, 172 (43.1%) were males and 227 (56.9%) were females. The mean age was 52.4 years (SD 11.6). Overall, 61.5% of patients were overweight (36.7%) or obese (24.8%). The mean duration of psoriasis since first diagnosis (N = 226) was 15.3 years (SD 12.2), whereas the mean duration of PsA (N = 392) was 7.2 years (SD 6.9). The socio-demographic and main clinical characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Regarding type of PsA, 44.6% (N = 178) of patients had symmetric polyarthritis, 38.8% (N = 155) asymmetric oligoarthritis, 20.3% (N = 81) spondylitis, 4.8% (N = 19) predominant distal interphalangeal arthritis, and 0.8% (N = 3) arthritis mutilans. Among eligible patients, 60.9% (N = 243) had comorbidities at enrollment, the most common being hypertension (N = 127, 31.8%), followed by diabetes (N = 38, 9.5%) and hypercholesterolemia/dyslipidemia (N = 37, 9.3%). Other reported comorbidities were: thyroid diseases (N = 32, 8.0%), obesity (N = 25, 6.3%), autoimmune diseases (N = 21, 5.3%), osteoporosis (N = 20, 5.0%), fibromyalgia (N = 16, 4.0%), depression (N = 15, 3.8%), asthma (N = 12, 3.0%), hepatitis (N = 9, 2.3%).

In the eligible population, the most commonly used biologic treatment under analysis was secukinumab (40.4%; N = 161), followed by adalimumab (biosimilars included, 17.8%; N = 71), and etanercept (biosimilars included, 16.5%; N = 66). Other biologic treatments under analysis were: certolizumab (9.8%; N = 39), ustekinumab (7.5%; N = 30), golimumab (5.0%; N = 20) and infliximab (biosimilars included, 3.0%; N = 12). TNF-inhibitors were used by 52.1%; (N = 208) of the patients.

While 46.6% (N = 186) of the patients were naïve to biologics, 33.3% (N = 133), 10.0% (N = 40), 6.8% (N = 27) and 3.3% (N = 13) had received one, two, three, four or more lines, respectively. The total mean duration of the biologic treatment under analysis was 18.6 (SD 6.5) months; overall, 97.7% (N = 390) had been on treatment for ≥ 6 months, whereas the median duration of exposure to any biologics since the diagnosis of PsA until the end of observation was 23.9 (25th–75th percentile: 17.2–37.9) months.

In patients on secukinumab 42.9% were naïve to biologics, 31.1% had received 1 previous biologic line and 26.1% received ≥ 2 previous biologic lines; in patients treated with TNFi 51.9% were naïve to biologics, while 33.2% and 14.9% had received 1 or ≥ 2 previous biologic lines, respectively.

Other factors as age, gender, ethnicity, smoking status, BMI, comorbidities, PsA manifestation, time since PsA and Pso diagnosis, months of exposure to biologic therapy under analysis, number of lines received during study, DAS28 at start of biologic therapy under analysis were largely similar across the treatment groups (see Additional file 1).

Concomitant topical treatments were used for psoriasis by 8.0% of study patients (N = 32), mainly topical corticosteroids (6.0%, N = 24) or vitamin D analogues (3.5%, N = 14). One patient received phototherapy. Systemic pharmacological treatments for PsA or psoriasis other than biologics were received by 46.6% (N = 186), mainly methotrexate (28.1%), non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs, 12.3%), and systemic corticosteroids, either orally or parenterally (10.8%) (Table 2).

Rehabilitation therapy was received by 5 patients (1.3%), either physiotherapy (N = 4) or kinesiotherapy (N = 1).

Primary objective: effectiveness

The proportion of patients with DAS28 ESR or DAS28 CRP > 3.2 decreases after 6 months and 1 year of treatment (Fig. 3).

Among the evaluable patients, the proportion of overall responders according to EULAR DAS28 criteria was 71.8% (95% CI: 66.7–76.8%) at 6 months and 68.0% (95% CI: 62.7–73.3%) at 1 year. The proportions of DAS28 responders at 6 months and 1 year for the secukinumab-treated and the TNFi-treated patients were 73.4% (95% CI: 65.8–81.1%). 69.6% (95% CI: 61.5–77.7%), and 71.9% (95% CI: 64.9–78.8%), 70.5% (95% CI: 63.1–77.8%) respectively.

In the overall population, ACR20, ACR50 and ACR70 responder rates were 41.2%, 29.4%, 17.1% at 6 months, and 34.9%, 26.7%, 18.4%, at 1 year, respectively. The response rates by treatment subgroups are detailed in Table 3.

The number of patients with dactylitis decreased from 35 at start of therapy (23.6% out of 148 patients with available evaluation) to 5 already at 6 months (3.5% out of 142 patients with available evaluation; details in Table 4).

Overall patients with enthesitis were 33.3% at start of therapy (N = 49 out of 147 patients with available evaluation of enthesitis) and decreased to 9.0% at 6 months (N = 12 out of 133 patients with available evaluation of enthesitis). Details on the progress of enthesitis at the different locations are reported in Table 4. Patients with evaluation of axial arthritis were only 102 at baseline, 82 at 6 months and 76 at 1 year. Among those, 56.9% had axial arthritis at start of therapy (N = 58 out of 102), 48.8% at 6 months (N = 40 out of 82) and 46.1% at 1 year (N = 35 out of 76).

Secondary objectives

In terms of extent and severity of psoriasis, the mean (SD) PASI at start of therapy, after 6 months and 1 year in the overall eligible patients with available score at time points (N = 87) were 3.2 (5.1), 0.6 (1.3) and 0.6 (1.3), respectively. The PASI decreased on average (SD) between the start of therapy and the 6-month assessment of 2.7 (4.6) points and of 2.6 (4.7) points between the start of therapy and 1 year.

Patients’ functional status was of mild-moderate disability at treatment start. The mean (SD) HAQ-DI in the overall eligible population with available HAQ-DI at all timepoints (N = 65) was 0.9 (0.6) at treatment start, and 0.7 (0.6) at 6 and 12 months. The mean (SD) decrease in HAQ-DI between the start of therapy and the 6-month assessment was 0.2 (0.6) and remained substantially the same between the start of therapy and 1 year (mean (SD) decrease: 0.2 (0.7)).

Lastly, the TSQM-9 subdomain assessment showed mean scores at enrolment visit (N = 396) of 66.1 (SD 21.9) for effectiveness, 77.0 (16.0) for convenience, and 66.7 (18.4) for global satisfaction and slightly increased at the 6-month follow-up visit (N = 365) to 69.2 (20.3), 78.3 (15.0), and 67.9 (18.4), respectively.

Only 19 patients out of 399 (4.8%) discontinued the biologic during the study and 33 (8.3%) switched to a different biological. The high persistence on biologic treatment was confirmed by the Kaplan–Meier analysis, showing 6-month and 1-year probabilities of treatment discontinuation/switch of 3% and 7%, respectively (Kaplan–Meier survival curve is shown in Fig. 4).

Discussion

Our study was designed with the aim of providing real world data on the effectiveness of biologics in the treatment of PsA in the Italian clinical practice. In our PsA population, almost all patients were or had been on the analyzed biologic treatment for at least 6 months, with an average duration of treatment of over one and a half years. Overall, the mean duration of any biologic treatment since PsA diagnosis was over 2 years. For almost half of our patients, the biologic treatment under analysis was the first biologic medication assumed. Other systemic treatments for PsA were taken by almost half of patients (46.6%) and consisted mainly in methotrexate (28.1%), whose possible association with biologicals is actually foreseen in the indications of many biological medications.

Regarding the primary objective, unfortunately we had almost 20% fewer evaluable patients among the eligible ones, due to lack of available information about the DAS28 response. The analysis performed to highlight any differences between patients with and without available clinical response gave somewhat contradictory information: patients with available data had higher duration of PsA but had received fewer biologic therapies during study, which does not allow to establish whether they were more or less likely to respond to the biological under analysis. The overall EULAR DAS28 responder rate at 6 months was rather high (71.8%). Between-treatment comparisons were not in the scope of our study; however, given that most of the patients were treated with secukinumab or TNFis, we also looked separately into the results of these two major treatment subgroups. A similar response was observed in both treatment subgroups at 6 months (73.4% with secukinumab, 71.9% with TNFis). At 1 year, the overall responder rate was a little lower (68.0%), similar in both treatment subgroups (69.6% with secukinumab, 70.5% with TNFis). Given that TNFis are usually used earlier in the biological treatments’ progression in the Italian clinical practice, to better characterize the two larger treatment subgroups in our study, we checked whether there were some differences in the number of biological lines assumed before study treatments in the two main treatment subgroups; even if no statistical differences were observed between treatment groups, there are more bio-naive patients in TNFi group and this may have influenced the effectiveness since bio-naive patients respond better than bio-experienced patients (see Additional file 1).

Considering ACR criteria, responders were somewhat more with secukinumab at 6 months but tended to be lower at 1 year. The ACR response rates allow us to better compare our real-life data with those of the literature. For example, in the secukinumab FUTURE 1 and 2 pivotal trials in PsA [39, 40], ACR20 response rates at 6 months were between 50 and 54% and were maintained through 1 year. In our study, response rates are lower. What was more striking, is that our ACR response rates, unlike in RCTs, showed to lower over time, even from 6 months to 1 year. Also looking at the pivotal RCTs of the other most frequently used biological treatments in our study, i.e. adalimumab [41] and etanercept [42, 43], ACR responses in RCTs are more or less higher than in the CHRONOS study and again are reported, at least up to 1 year, to be maintained. Typically, patients and the course of treatment in the daily clinical practice are different from RCTs: real world studies include different patient population than RCTs, less selected, less homogeneous, often with more comorbidities and previously exposed to different biologic treatments [44, 45]. Furthermore, data from registries have suggested that biological agents’ doses are generally lower than those indicated in the drug labels [46]. Moreover, overweight and obese patients were highly represented in our cohort and it has been reported that obesity may hamper the effect of some biologic agents in axial spondyloarthritis and PsA [47]. Looking at the specific clinical features of PsA, treatment with biologicals in our patients showed to reduce dactylitis and enthesitis rapidly and dramatically. A modest reduction in the proportion of patients with axial arthritis was observed during the study. According to clinical practice, evaluation of axial arthritis was performed in a small proportion of patients (26% and < 20% of eligible patients had available evaluation at start of therapy and at 1 year, respectively). Also, dactylitis and enthesitis seem not to be routinely performed (34% and 37% of eligible patients had available evaluation at start of therapy and at 1 year, respectively). Therefore, the reliability of these positive results, especially those about axial arthritis, is somewhat impaired due to the limited and decreasing number of patients with available data.

The skin burden of psoriasis was low at start of therapy, suggesting that psoriasis was already under a rather good control in these PsA patients. Nevertheless, the mean PASI decreased after 6 months showing an improving of the skin disease. At start of therapy, our patients had a mild disability that improved slightly during biological treatment, likely due to the already low initial level of impairment. Treatment withdrawals and switches were few, confirming the high persistence with biological treatments reported in the literature [48,49,50,51]. Consistently, patients’ satisfaction with the study treatment was rather high for all three TSQM-9 domains.

The limitations of the CHRONOS are mainly due to its observational nature. Regarding potential confounders, the population could be in some way heterogeneous, in terms of clinical history, previous treatments for PsA, durations of observation and number of biologic lines. Moreover, there might have been some differences in patients’ characteristics by treatment group (as higher number of previous biologic therapies), somehow affecting results of the stratified response analyses; however, main potential confounding factors were evaluated and resulted well balanced by treatment group (see Additional file 1). Another limitation may consist in a certain inhomogeneity in the quality of the collected data since the study included both a retrospective and a prospective period. Furthermore, since biologic medications were generally injected at home, it is possible that in certain cases patients were not fully compliant to the prescribed regimen (in terms of posology, frequency of administration, stopping rules, etc.), which may have affected somewhat their effectiveness, especially in the longer term. In addition, not all enrolled patients had available complete data on clinical response at all time points. In order to manage this potential selection bias, as already discussed, patients with and without available response at 6 months and 1 year were compared in relation to the main patient characteristics at the start of biologic treatment. One of the actions put in place in order to reduce the impact of such missing data on study objectives evaluation was the enlargement of the tolerability windows of the main outcomes during data analysis, considering as valid from a clinical point of view also data collected few months before or after the planned time points of interest. This action allowed to reach a total number of patients evaluable for the primary objective at 6 months of 308, about 9% lower than the planned sample size but, as already pointed out, allowing precise estimates of the primary endpoints.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the CHRONOS study provides real-world data on the effectiveness of biologics in PsA in the Italian rheumatological daily practice. Our results confirm the efficacy of biologic therapy reported in RCTs across various outcome measures, including patients’ satisfaction, although to a generally lower extent which might be due some of the study limitations. Persistence on biologic treatment up to 1 year was high with low probabilities of treatment discontinuation or switch.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from authors and Novartis Farma S.p.A. but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of the authors and Novartis Farma S.p.A.

Abbreviations

- ACR:

-

American College of Rheumatology

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- DAS28:

-

Disease activity score 28 joints

- DMARDs:

-

Disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs

- ESR:

-

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- EULAR:

-

European league against rheumatism

- GH:

-

General health

- HAQ-DI:

-

Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index

- IL:

-

Interleukin

- LEI:

-

Leed Enthesitis Index

- PASI:

-

Psoriasis Area and Severity Index

- PsA:

-

Psoriatic arthritis

- RCTs:

-

Randomized clinical trials

- RWE:

-

Real-world evidence

- TNFis:

-

TNF inhibitors

- TSQM-9:

-

Treatment satisfaction questionnaire for medication-9

References

Ritchlin C. Psoriatic disease—from skin to bone. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2007;3(12):698–706.

Pollock RA, Abji F, Gladman DD. Epigenetics of psoriatic disease: a systematic review and critical appraisal. J Autoimmun. 2017;78:29–38.

Ritchlin CT, Colbert RA, Gladman DD. Psoriatic arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(10):957–70.

Coates LC, Helliwell PS. Psoriatic arthritis: state of the art review. Clin Med (Lond). 2017;17(1):65–70.

Singh JA, Guyatt G, Ogdie A, Gladman DD, Deal C, Deodhar A, et al. Special article: 2018 American College of Rheumatology/National Psoriasis Foundation Guideline for the treatment of psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2019;71(1):2–29.

Catanoso M, Pipitone N, Salvarani C. Epidemiology of psoriatic arthritis. Reumatismo. 2012;64:66–70.

Mease PJ, Gladman DD, Papp KA, Khraishi MM, Thaçi D, Behrens F, et al. Prevalence of rheumatologist-diagnosed psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis in European/North American dermatology clinics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:729–35.

Lie E, Fagerli KM, Mikkelsen K, Rodevand E, Lexberg A, Kalstad S, et al. First-time prescriptions of biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis and axial spondyloarthritis 2002–2011: data from the NOR-DMARD register. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:1905–6.

Elalouf O, Chandran V. Novel therapeutics in psoriatic arthritis. What is in the pipeline? Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2018;20(7):36.

Coates LC, Gossec L, Ramiro S, Mease P, van der Heijde D, Smolen JS, et al. New GRAPPA and EULAR recommendations for the management of psoriatic arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2017;56(8):1251–3.

Lories RJ, deVlam K. Tumour necrosis factor inhibitors in the treatment of psoriatic arthritis: a view on effectiveness, clinical practice and toxicity. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2014;14:1825–36.

Kavanaugh A, Puig L, Gottlieb AB, Ritchlin C, Li S, Wang Y, et al. Maintenance of clinical efficacy and radiographic benefit through two years of ustekinumab therapy in patients with active psoriatic arthritis: results from a randomized, placebo-controlled phase III trial. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2015;67:1739–49.

McInnes IB, Mease PJ, Kirkham B, Kavanaugh A, Ritchlin CT, Rahman P, et al. Secukinumab, a human anti-interleukin-17A monoclonal antibody, in patients with psoriatic arthritis (FUTURE2): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2015;386:1137–46.

Curtis JR, Mariette X, Gaujoux-Viala C, Blauvelt A, Kvien TK, Sandborn WJ, et al. Long-term safety of certolizumab pegol in rheumatoid arthritis, axial spondyloarthritis, psoriatic arthritis, psoriasis and Crohn’s disease: a pooled analysis of 11 317 patients across clinical trials. RMD Open. 2019;5(1):e000942.

Love TJ, Kavanaugh A. Golimumab in the treatment of psoriatic arthritis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2018;14(11):893–8.

Mease PJ, van der Heijde D, Ritchlin CT, Okada M, Cuchacovich RS, Shuler CL, et al. SPIRIT-P1 Study Group. Ixekizumab, an interleukin-17A specific monoclonal antibody, for the treatment of biologic-naive patients with active psoriatic arthritis: results from the 24-week randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled and active (adalimumab)-controlled period of the phase III trial SPIRIT-P1. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(1):79–87.

DAS28-EULAR Response criteria [online] Available at: [Accessed September, 2020].

Salaffi F, Ciapetti A, Carotti M, Gasparini S, Gutierrez M. Disease activity in psoriatic arthritis: comparison of the discriminative capacity and construct validity of six composite indices in a real world. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:528105.

Naranje P, Prakash M, Sharma A, Dogra S, Khandelwal N. Ultrasound findings in hand joints involvement in patients with psoriatic arthritis and its correlation with clinical DAS28 score. Radiol Res Pract. 2015;2015:353657.

Nash P, Ohson K, Walsh J, Delev N, Nguyen D, Teng L, Gómez-Reino JJ, Aelion JA. ACTIVE investigators. Early and sustained efficacy with apremilast monotherapy in biological-naïve patients with psoriatic arthritis: a phase IIIB, randomised controlled trial (ACTIVE). Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77(5):690–8.

Chiricozzi A, Burlando M, Caldarola G, Conti A, Damiani G, De Simone C, et al. Ixekizumab effectiveness and safety in the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: a multicenter, retrospective observational study. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020;21(3):441–7.

Prevoo ML, van ’t Hof MA, Kuper HH, van Leeuwen MA, van de Putte LB, van Riel PL. Modified disease activity scores that include twenty-eight-joint counts. Development and validation in a prospective longitudinal study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38(1):44–8.

Felson DT, Anderson JJ, Boers M, Bombardier C, Chernoff M, Fried B, et al. The American College of Rheumatology preliminary core set of disease activity measures for rheumatoid arthritis clinical trials. The committee on outcome measures in rheumatoid arthritis clinical trials. Arthritis Rheum. 1993;36(6):729–40.

Mease PJ, McInnes IB, Kirkham B, Kavanaugh A, Rahman P, van der Heijde D, et al. For the FUTURE 1 Study Group. Secukinumab inhibition of interleukin-17A in patients with psoriatic arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1329–39.

McInnes IB, Mease PJ, Kirkham B, Kavanaugh A, Ritchlin CT, Rahman P, et al. On behalf of the FUTURE 2 Study Group. Secukinumab, a human anti-interleukin-17A monoclonal antibody, in patients with psoriatic arthritis (FUTURE 2): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2015;386:1137–46.

Kavanaugh A, Mease PJ, Reimold AM, Tahir H, Rech J, Hall S, et al. For the FUTURE-1 Study Group. Secukinumab for long-term treatment of psoriatic arthritis: a two-year follow up from a phase III, randomized, Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Study. Arthritis Care Res. 2017;69(3):347–55.

Mease PJ, Rahman P, Gottlieb AB, Kollmeier AP, Hsia EC, Xu XL, et al. DISCOVER-2 Study Group. Guselkumab in biologic-naive patients with active psoriatic arthritis (DISCOVER-2): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2020;395(10230):1126–36.

Fries JF, Spitz P, Kraines RG, Holman H. Measurement of patient outcome in arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1980;23:137–45.

Atkinson MJ, Sinha A, Hass SL, Colman SS, Kumar RN, Brod M, Rowland CR. Validation of a general measure of treatment satisfaction, the treatment satisfaction questionnaire for medication (TSQM), using a national panel study of chronic disease. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2004;2:12.

Atkinson M, Kumar R, Cappelleri JC, Hass SL. Hierarchical construct validity of the treatment satisfaction questionnaire for medication (TSQM version II) among outpatient pharmacy consumers. Value Health. 2005;8(Suppl 1):S9–24.

Carmona L, Gómez-Reino JJ. Survival of TNF antagonists in spondylarthritis is better than in rheumatoid arthritis. Data from the Spanish registry BIOBADASER. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8:R72.

Glintborg B, Østergaard M, Dreyer L, Krogh NS, Tarp U, Hansen MS, et al. Treatment response, drug survival, and predictors thereof in 764 patients with psoriatic arthritis treated with anti-tumor necrosis factor α therapy: results from the nationwide Danish DANBIO registry. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:382–90.

Kristensen LE, Gülfe A, Saxne T, Geborek P. Efficacy and tolerability of anti-tumour necrosis factor therapy in psoriatic arthritis patients: results from the South Swedish Arthritis Treatment Group register. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:364–9.

Heiberg MS, Koldingsnes W, Mikkelsen K, Rødevand E, Kaufmann C, Mowinckel P, et al. The comparative one-year performance of anti-turmor necrosis factor α drugs in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis: results from a longitudinal, observational, multicenter study. Arthritis Care Res. 2008;59:234–40.

Saad AA, Ashcroft DM, Watson KD, Hyrich KL, Noyce PR, Symmons DPM. Persistence with antitumour necrosis factor therapies in patients with psoriatic arthritis: observational study from the British Society of Rheumatology Biologics Register. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11:R52.

Saad AA, Ashcroft DM, Watson KD, Symmons DPM, Noyce PR, Hyrich KL. Efficacy and safety of anti-TNF therapies in psoriatic arthritis: an observational study from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register: reply. Rheumatology. 2010;49:697–705.

Virkki LM, Sumathikutty BC, Aarnio M, Valleala H, Heikkilä R, Kauppi M, et al. Biological therapy for psoriatic arthritis in clinical practice: outcomes up to 2 years. J Rheumatol. 2010;37:2362–8.

Fagerli KM, Lie E, van der Heijde D, Heiberg MS, Lexberg AS, Rødevand E, et al. The role of methotrexate co-medication in TNF-inhibitor treatment in patients with psoriatic arthritis: results from 440 patients included in the NOR-DMARD study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:132–7.

Mease PJ, Kavanaugh A, Reimold A, Tahir H, Rech J, Hall S, et al. Secukinumab in the treatment of psoriatic arthritis: efficacy and safety results through 3 years from the year 1 extension of the randomised phase III FUTURE 1 trial. RMD Open. 2018;4(2):e000723.

Coates LC, Gladman DD, Nash P, FitzGerald O, Kavanaugh A, Kvien TK, et al. FUTURE 2 study group. Secukinumab provides sustained PASDAS-defined remission in psoriatic arthritis and improves health-related quality of life in patients achieving remission: 2-year results from the phase III FUTURE 2 study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2018;20(1):272.

Mease PJ, Gladman DD, Ritchlin CT, Ruderman EM, Steinfeld SD, Choy EH, et al. Adalimumab for the treatment of patients with moderately to severely active psoriatic arthritis: results of a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:3279–89.

Mease PJ, Kivitz AJ, Burch FX, Siegel EL, Cohen SB, Ory P, et al. Etanercept treatment of psoriatic arthritis: safety, efficacy, and effect on disease progression. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:2264–72.

Mease PJ, Goffe BS, Metz J, VanderStoep A, Finck B, Burge DJ. Etanercept in the treatment of psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2000;356(9227):385–90.

Yiu ZZN, Mason KJ, Barker JNWN, Hampton PJ, McElhone K, Smith CH, et al. A standardization approach to compare treatment safety and effectiveness outcomes between clinical trials and real-world populations in psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181(6):1265–71.

van Lümig PP, van de Kerkhof PC, Boezeman JB, Driessen RJ, de Jong EM. Adalimumab therapy for psoriasis in real-world practice: efficacy, safety and results in biologic-naive vs. non-naive patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27(5):593–600.

Zagni E, Colombo D, Fiocchi M, Perrone V, Sangiorgi D, Andretta M. Pharmaco-utilization of biologic drugs in patients affected by psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis in an Italian real-world setting. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2020;23:1–7.

Shan J, Zhang J. Impact of obesity on the efficacy of different biologic agents in inflammatory diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Joint Bone Spine. 2019;86(2):173–83.

Walsh JA, Gottlieb AB, Hoepken B, Nurminen T, Mease PJ. Efficacy of certolizumab pegol with and without concomitant use of disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs over 4 years in psoriatic arthritis patients: results from the RAPID-PsA randomized controlled trial. Clin Rheumatol. 2018;37(12):3285–96.

Bonafede M, Johnson BH, Fox KM, Watson C, Gandra SR. Treatment patterns with etanercept and adalimumab for psoriatic diseases in a real-world setting. J Dermatolog Treat. 2013;24(5):369–73.

Iannone F, Lopriore S, Bucci R, Lopalco G, Chialà A, Cantarini L, Lapadula G. Longterm clinical outcomes in 420 patients with psoriatic arthritis taking anti-tumor necrosis factor drugs in real-world settings. J Rheumatol. 2016;43(5):911–7.

Yiu ZZN, Mason KJ, Hampton PJ, Reynolds NJ, Smith CH, Lunt M, et al. BADBIR Study Group. Drug survival of adalimumab, ustekinumab and secukinumab in patients with psoriasis: a prospective cohort study from the British Association of Dermatologists Biologics and Immunomodulators Register (BADBIR). Br J Dermatol. 2020;183(2):294–302.

Acknowledgements

The authors meet the criteria of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) for authorship and were fully responsible for all aspects of manuscript development. We are grateful to Renata Perego for her help in drafting the manuscript. We are also grateful to the participating centers, involved in data collection.

CHRONOS Study Group

Frassi Micol2 ASST Spedali Civili, Brescia, Italy.

Caminiti Maurizio3 Grande Ospedale Metropolitano Bianchi Melacrino Morelli, Reggio Calabria, Italy

Fusaro Enrico4 AOU Città della Salute e della Scienza di Torino, Turin, Italy.

Lomater Claudia5 A.O. Mauriziano, Turin.

Del Medico Patrizia6 Ospedale civile, Civitanova Marche, Italy.

Iannone Florenzo7 A.O.U. Policlinico Consorziale, Bari, Italy.

Foti Rosario8 A.O.U. Policlinico - Vittorio Emanuele, Catania, Italy.

Limonta Massimiliano9 ASST Papa Giovanni XXIII, Bergamo, Italy.

Marchesoni Antonio10 ASST Gaetano Pini-CTO, Milan, Italy.

Raffeiner Bernd11 Ospedale Centrale di Bolzano, Bolzano, Italy.

Viapiana Ombretta12 AOUI Verona Borgo Roma, Verona, Italy.

Grassi Walter13 Policlinico A. Murri, Jesi, Italy.

Grembiale Rosa Daniela14 A.O.U. Mater Domini, Catanzaro, Italy.

Guggino Giuliana15 A.O.U. Policlinico Giaccone, Palermo, Italy.

Mazzone Antonino16 Ospedale Civile di Legnano, Legnano, Italy.

Tirri Enrico17 Ospedale San Giovanni Bosco, Naples, Italy.

Perricone Roberto18 Policlinico Tor Vergata, Rome, Italy.

Sarzi Puttini Pier Carlo19 ASST FBF Sacco, Milan, Italy.

De Vita Salvatore20 ASUIUD, Udine, Italy.

Conti Fabrizio21 Azienda Policlinico Umberto I, Rome, Italy.

Funding

The study was supported by a grant from Novartis Farma S.p.A. Origgio (VA), Italy.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

DC, EZ, MF, RO, AO, LS provided contribution to conception and design of the work and to interpretation of the data. MF, GPM, FE, CL, PDM, FI, RF, ML, AM, BR, OV, WG, RDG, GG, AM, ET, RP, PCSP, SDV, FC provided contribution to data collection. LS provided contribution to data analysis and drafting of the paper. All authors reviewed the paper, provided their approval to the version to be submitted for publication, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted in accordance with the amended Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approvals for this study was obtained from each participating site according to Italian Regulation applicable for prospective observational studies. The patients provided written informed consent before the data collection. The study was approved by the Ethic Committee of the coordinating center (A.O.U. Policlinico-Vittorio Emanuele P.O. San Marco, Catania, Italy) and then by the Ethic Committees of all the participating centers.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

DC was a part-time employee of Novartis Farma Italy when the study was conducted. AM has received honoraria and speaker fees from Abbvie, Amgen, Eli-Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, Janssen, and UCB. AO is employee of MediNeos Observational Research (Modena, Italy), hired by Novartis Farma Italy, responsible for the design and conduction of the CHRONOS study, as well as scientific support, clinical operations, data management, statistical analysis. LS is employee of MediNeos Observational Research (Modena, Italy), hired by Novartis Farma Italy, responsible for the design and conduction of the CHRONOS study, as well as scientific support, clinical operations, data management, statistical analysis.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1

: Socio-demographic and clinical characteristics at enrollment/start of biologic treatment under analysis (in Secukinumab and TNFis patients). In this file main socio-demographic and clinical characteristics at enrollment/start of biologic treatment under analysis are described in the groups of patients treated with Secukinumab and with TNFis.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Colombo, D., Frassi, M., Pagano Mariano, G. et al. Real-world evidence of biologic treatments in psoriatic arthritis in Italy: results of the CHRONOS (EffeCtiveness of biologic treatments for psoriatic artHRitis in Italy: an ObservatioNal lOngitudinal Study of real-life clinical practice) observational longitudinal study. BMC Rheumatol 6, 57 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41927-022-00284-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41927-022-00284-w