Abstract

Background

Water use efficiency (WUE) is an indicator of the trade-off between carbon uptake and water loss to the atmosphere at the plant or ecosystem level. Understanding temporal dynamics and the response of WUE to climatic variability is an essential part of land degradation assessments in water-limited dryland regions. Alternative definitions of and/or alternative methodologies used to measure WUE, however, have hampered intercomparisons among previous studies of different biomes and regions. The present study aims to clarify semantic differences among WUE parameters applied in previous studies and summarize these parameters in terms of their definition and methodology.

Additionally, the consistency of the responses of alternative WUE parameters to interannual changes in moisture levels in Northeast Asia dryland regions (NADRs) was tested.

Results

The literature review identified more than five different WUE parameters defined at leaf and ecosystem levels and indicates that major conclusions regarding the WUE response to climatic variability were partly inconsistent depending on the parameters used. Our demonstration of WUE in NADR again confirmed regional inconsistencies and further showed that inconsistencies were more distinct in hyper- and semi-arid climates than in arid climates, which might reflect the different relative roles of physical and biological processes in the coupled carbon–water process.

Conclusions

The responses of alternative WUE parameters to drying and wetting may be different in different regions, and regionally different response seems to be related to aridity, which determines vegetation coverage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Drylands are characterized by an aridity index (ratio of annual rainfall to potential evapotranspiration) lower than 0.65(Serrano-Ortiz et al. 2012) and cover about 40% of land worldwide (Reynolds et al. 2007). These water-limited and fragile ecosystem are very sensitive to perturbations such as drought, fires, or climate change (Björkman and Powles 1984; Flexas et al. 2006; Chen et al. 2017), leading to desertification (Mouat and Lancaster 2006), which alters the ecosystem carbon–water cycles (Oki and Kanae 2006), such as carbon pool decreases and soil evaporation increases. The most widely used indicators for carbon processes are gross primary productivity (GPP), net primary productivity (NPP), ecosystem respiration, gross ecosystem production (GEP), net ecosystem CO2 exchange (NEE), and precipitation, evaporation, transpiration, and soil moisture for water processes. Water use efficiency (WUE) is a measure of the trade-off between carbon gain and water loss in plants or terrestrial ecosystems (Liu et al. 2015), both of which are related to photosynthesis and evapotranspiration processes, respectively. Hence, as an integrative measure of carbon and water processes, WUE has been a focus of dryland studies at various spatial scales from site to regional or continental (Emmerich 2007; Niu et al. 2011; Tang et al. 2017).

In previous studies, WUE was defined in various ways. Microscale WUE, which is preferred in laboratory and field experiments, is a measure of leaf-level gas exchange or stable isotope discrimination (Niu et al. 2011; Medlyn et al. 2017). Macroscale WUE, which is applied to entire forest canopies and land surfaces, is estimated with eddy covariance flux towers and estimates of gross primary production (GPP) and evapotranspiration (ET) based on remote sensing (Huang et al. 2015; Sun et al. 2015). Further, researchers have used different definitions of WUE depending on their questions and monitoring methods. For example, WUE has been defined as the ration of carbon gain (e.g., GPP) to water loss (e.g., ET) or alternatively as the ratio of instantaneous photosynthesis to stomata conduction (Beer et al. 2009; McCarthy et al. 2011; Sun et al. 2015).

The different definitions and methods used to estimate WUE have inevitably resulted in confusion in comparing WUE and deepening our understanding of the relationship between changes in carbon and water flux and climate change and variability. In particular, they have led to uncertainty in monitoring and evaluating the response of WUE to droughts or regime shifts in water-limited dryland ecosystems, in which remote sensing data has been widely applied to assess WUE due to the huge geographic areas involved and their remoteness (Niu et al. 2011; Sun et al. 2015).

In the present study, we reviewed various definitions and methodologies of WUE estimation that have been applied in previous studies. To highlight that alternative WUE parameters can show different responses to interannual climatic variations, we mapped and compared correlation coefficients between a drought index and three different WUE parameters derived from satellite data in Northeast Asia dryland regions (NADRs).

Various definitions and methodologies of WUE estimation

Definition

A great deal of the literature focuses on leaf- or ecosystem-scale WUE (Zhu 2013). At the leaf scale, WUE has been defined as the ratio of instantaneous photosynthesis (A) to transpiration (T) (Simioni et al. 2004; Sun et al. 2015), which is mostly controlled by stomata opening and closure (Huang et al. 2017a). Intrinsic water use efficiency (WUEi) has also been utilized to reflect the biochemical characteristics of plants based on photosynthesis (A) and stomata conductance (g) (Beer et al. 2009; McCarthy et al. 2011).

At the ecosystem scale, WUE is generally defined as the ratio of GPP to ET. Instead of GPP, some researchers use net primary production (NPP), gross ecosystem production (GEP), net ecosystem CO2 exchange (NEE) (Hu et al. 2009; Potts et al. 2010; Yu and Wang 2010), or even crop yield for crop WUE (Tallec et al. 2013). Other research takes ecophysiological characteristics into consideration to separate ecosystem WUE (GPP/ET) into two terms, that is, (GPP/T) × (T/ET). The former term (GPP/T) is a measure of how efficiently plants use water to produce organic material, called transpiration-based WUE (WUEt) (Ponton et al. 2006; Niu et al. 2011; Sun et al. 2015). The latter term (T/ET) is the ratio of transpiration to evapotranspiration, which reflects how physical (i.e., evaporation, E) and biological (i.e., T) processes account for ecosystem water vapor flux (Hu et al. 2008). In drylands with sparse vegetation (i.e., grasslands), evaporation from the soil surface accounts for a high proportion of the whole-ecosystem ET (Ferretti et al. 2003; Hu et al. 2008), meaning that each water loss component must be considered separately when estimating WUE in such drylands.

When extrapolating leaf-level intrinsic WUE to the canopy scale, Beer et al. (2009) assumed the difference between ambient and inner-leaf water vapor pressure to be the vapor pressure deficit (VPD). However, the method neglected to consider aerodynamic resistance through the leaf boundary layer, thus calculating inherent WUE (IWUE). Meanwhile, the slope of linear regression between vegetation productivity and ET has been considered equal to WUE so that one can compare the differences among ecosystems (Brümmer et al. 2012; Shurpali et al. 2013). Notably, due to a lack of ET data at the regional scale, precipitation has frequently been used to replace ET as a proxy of WUE called rainfall use efficiency (RUE) (Yang et al. 2010; Zhang et al. 2013). The various definitions are summarized in Table 1. The different definitions of WUE represent different ecological processes or inherent mechanisms at different spatial scales (Table 1). For example, emphasis on hydrological processes increases from WUEt to WUE and RUE (Hu et al. 2009), and vice versa for biological process.

Methodology

The various methodologies of WUE estimation also reflect the diversity of WUE studies (Table 1). At the leaf level, leaf gas exchange and stable carbon isotope discrimination are the most common methods used to estimate WUE. The leaf gas exchange method measures the instantaneous photosynthetic rate (A) and transpiration (T) of leaves for plant species (Niu et al. 2011) or plant functional types (e.g., C3 and C4 grass; Lin et al. 2015). The high sensitivity of instantaneous WUE to ecophysiological and environmental conditions, however, increases uncertainty in data intercomparisons (Luo et al. 2009). In contrast, because δ13C is related to the difference between ambient and inner-leaf carbon dioxide partial pressure, it has been used to indirectly estimate stomata conductance (g) and, further, intrinsic WUE (WUEi) (Farquhar et al. 1982; Casper et al. 2005). The stable isotope method focuses on carbon gain and water loss during growing seasons and provides a longer temporal record of vegetation ecophysiological process than the gas exchange method.

At the ecosystem level, eddy covariance (EC) flux data and satellite-based biophysical models have been widely used to assess ecosystem WUE and its response to climatic variability at various spatial scales from site to regional or continental (Huang et al. 2015; Yang et al. 2016; Chen et al. 2017; Medlyn et al. 2017) (Table 1). Although data quality and processing present issues with EC flux data, this method has been widely applied to estimate footprint-scale WUE for various plant function types (PFTs). Model and satellite remote sensing have also been applied to estimate ecosystem WUE using various process-based models (Huang et al. 2015; Sun et al. 2015; Chen et al. 2017) and satellite-based biophysical parameters, such as MODIS GPP and ET products (Tang et al. 2017). Sometimes, satellite-derived parameters are integrated into models to enhance accuracy (Liu et al. 2015).

To understand the inherent ecological mechanisms of WUE, some researchers have analyzed the response of WUE to climate change or drought. However, the results are not always consistent among studies because of differences in temporal and spatial scales (Huang et al. 2015; Huang et al. 2016), biomes (Gang et al. 2016; Yang et al. 2016; Huang et al. 2017a), and regions (Zhu et al. 2011; Huang et al. 2017b) (Table 1). For instance, WUE increases in mainly high latitudes and decreases at middle and low latitudes under climate change scenarios (Huang et al. 2015). The seasonal WUE trends are mainly associated with seasonal trends of climate (Huang et al. 2016), while the annual WUE changes result from the response of ecosystem (Zhu et al. 2011). The effects of precipitation on ecosystem WUE depend heavily on the stimulating effects of the dominant species in the plant community (Huang et al. 2017a). In particular, as Sun et al. (2015) suggested, two ET components (i.e., transpiration and evaporation) need to be analyzed separately when investigating regional WUE gradients across wide geographic regions where each component contributes differently to ET depending on biome type and vegetation coverage.

In summary, various WUE parameters have been used in studying coupled carbon–water processes, which has helped produce an increasing body of evidence regarding the response of these processes to past and future climatic variability on various scales from local to global. Semantic differences in parameters, however, highlight the need for the selection of appropriate WUE parameters or intercomparison of WUE for monitoring or evaluation as well as in diagnostic analyses of the response of WUE to climate variability (Huang et al. 2015; Huang et al. 2016; Yang et al. 2016).

Comparing correlations between drought index and alternative WUE parameters

Different WUE parameters can produce inconsistent results regarding plant responses to climatic variability in dryland ecosystems, where droughts occur regularly. As a case study, we demonstrated how alternative WUE parameters perform in estimating the WUE response to drought in NADR. For this, three ecosystem-level WUE parameters (i.e., WUEet, WUEt, and IWUEt, detailed in Table 1) were estimated from satellite-derived GPP and ET, where ET was further partitioned into T and E from 2003 to 2015. Additionally, 3-month standardized precipitation evapotranspiration index (SPEI) data were examined as a drought indictor using SPEIbase v.2.4 (Beguería et al. 2014). Based on the principle of water balance, the SPEI integrates the precipitation and potential evapotranspiration information to monitor drought conditions (Vicente-Serrano et al. 2010), which performs well in agricultural, ecological, and hydrological applications (Vicente-Serrano et al. 2012). The SPEI and WUE parameters were measured daily with spatial resolutions of 1 km and 0.5°, respectively.

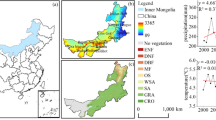

ET and GPP were estimated with the revised RS-PM algorithm (Mu et al. 2007; Mu et al. 2011; Jang et al. 2013) and the Vegetation Photosynthesis Model (VPM, Xiao et al. 2004; Zhang et al. 2015). To implement the models, daily surface solar radiation, net radiation, daytime VPD, and air temperature (Ta) data were collected with Aqua MODIS satellite products following the methods described by Jang et al. (2014). The accuracy of the estimated GPP and ET was tested for ground-measured EC datasets at six flux towers in NADR covering various biomes from arid grassland to cropland and forest (Fig. 1). The estimated GPP and ET represented the observed values reasonably accurately, with correlation coefficients of 0.94 and 0.83 (p < 0.001) and root mean square errors of 0.88 gC m−2 day−1 and 0.59 mm day−1, respectively.

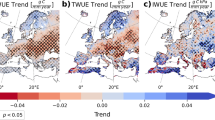

The responses of WUE parameters to drought were evaluated based on Pearson’s correlation coefficients (r) between WUE and SPEI values. The results indicated that parameters were generally similar but regionally different (Fig. 2). On one hand, the three WUE parameters showed concurrent negative correlations in eastern Kazakhstan, mid-western Mongolia, western Inner Mongolia, and northwestern China, while positive correlations partly occurred in central Inner Mongolia. The positive and negative correlations mean higher and lower sensitivity of biological process (i.e., GPP) rather than physical process (i.e., evaporation) to drought, respectively (Yang et al. 2016). Alternatively, the negative correlation can happen when drought-tolerant species (e.g., Tamarix ramosissima) become dominant (of Xu and Li 2006; Xu et al. 2007). On the other hand, inconsistent correlations were generally, but not necessarily, more distinct in hyper-arid deserts and less dry northern steppe than in the consistent regions mentioned above. For example, in central hyper-arid areas, including the Badan Jilin desert (Fig. 2), significant negative correlations with SPEI were distinct and extensive for WUEet, but only partly significant for WUEt and unclear for IWUEt. Our results illustrated the conservative response of IWUEt to drying and wetting, as Sun et al. (2015) found. On the contrary, significant positive relationships between WUEt and IWUEt and SPEI were distinct in the semi-arid northeastern Mongolia (Fig. 2) but the relationships of WUEet were unclear. Notably, the different responses of WUE parameters to drought might demonstrate different inherent mechanisms. The contrasting results mentioned above imply that (1) the responses of alternative WUE parameters to drying and wetting may be different in different regions and (2) regionally different responses seem to be related to aridity, which determines vegetation coverage.

The abovementioned consistency and inconsistency in correlation patterns are relevant with several drought-related mechanisms of plant and soils including (1) plant ecophysiological strategy on stomata opening and closing, (2) photosynthetic compensation of plant community, and (3) partitioning of ET into transpiration and evaporation (Hu et al. 2008; Sun et al. 2015). For example, in hyper-arid deserts, vegetation is sparse, drought-tolerant plants such as C4 herbs or shrubs become abundant, and water is lost to atmosphere primarily through evaporation from bare soils rather than plant transpiration, causing higher sensitivity of evaporation to dryness than GPP and transpiration, which could produce a negative correlation of WUEet to drought but null correlations in WUEt and IWUEt, respectively. Hence, analyzing each component flux of ecosystem WUE to climate changes and comparing the different response of WUE parameters at leaf and ecosystem level may provide more useful insights to understand the coupled carbon–water flux process in dryland ecosystems than different WUE parameters applied separately.

Conclusions

This study reviewed alternative WUE parameters as proposed by various researchers and clarified semantic differences among WUE parameters in terms of definitions and methodologies. Additionally, this study demonstrated where and how alternative WUE parameters show different responses to variations in moisture levels. The results illustrate the difficulty of intercomparison among WUE studies that use different definitions in different regions but, at the same time, highlight the usefulness of comparing alternative WUE parameters to understand the relative roles of physical and biological processes in determining the coupled carbon–water flux process and its response to climate variability. For this, each water loss component of WUE needs to be considered separately so that ecosystem process models and satellite data can be applied to enable data collection and comparison across wide geographic regions.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- A:

-

Instantaneous photosynthesis

- E:

-

Evaporation

- ET:

-

Evapotranspiration

- GEP:

-

Gross ecosystem production

- GPP:

-

Gross primary production

- IWUE:

-

Inherent water use efficiency

- NADR:

-

Northeast Asia dryland region

- NEE:

-

Net ecosystem CO2 exchange

- NPP:

-

Net primary production

- RUE:

-

Rainfall use efficiency

- SPEI:

-

Standardized precipitation evapotranspiration index

- T:

-

Transpiration

- VPD:

-

Vapor pressure deficit

- WUE:

-

Water use efficiency

- WUEi:

-

Intrinsic water use efficiency

References

Beer C, Ciais P, Reichstein M, Baldocchi D. Temporal and among-site variability of inherent water use efficiency at the ecosystem level. Glob Biogeochem Cycles. 2009;23:GB2018.

Beguería S, Vicente-Serrano SM, Reig F, Latorre B. Standardized precipitation evapotranspiration index (SPEI) revisited: parameter fitting, evapotranspiration models, tools, datasets and drought monitoring. Int J Climatol. 2014;34:3001–23.

Björkman O, Powles SB. Inhibition of photosynthetic reactions under water stress: interaction with light level. Planta. 1984;161:490–504.

Brümmer C, Black TA, Jassal RS, Grant NJ, Spittlehouse DL, Chen B, Nesic Z, Amiro BD, Arain MA, Barr AG. How climate and vegetation type influence evapotranspiration and water use efficiency in Canadian forest, peatland and grassland ecosystems. Agric For Meteorol. 2012;153:14–30.

Casper BB, Forseth IN, Wait DA. Variation in carbon isotope discrimination in relation to plant performance in a natural population of Cryptantha flava. Oecologia. 2005;145:541–8.

Chen Y, Li J, Ju W, Ruan H, Qin Z, Huang Y, Jeelani N, Padarian J, Propastin P. Quantitative assessments of water-use efficiency in Temperate Eurasian Steppe along an aridity gradient. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0179875.

Emmerich WE. Ecosystem water use efficiency in a semiarid shrubland and grassland community. Rangel Ecol Manag. 2007;60:464–70.

Farquhar GD, O'Leary MHO, Berry JA. On the relationship between carbon isotope discrimination and the intercellular carbon dioxide concentration in leaves. Aust J Plant Physiol. 1982;9:121–37.

Ferretti DF, Pendall E, Morgan JA, Nelson JA, Lecain D, Mosier ARJP. Partitioning evapotranspiration fluxes from a Colorado grassland using stable isotopes: seasonal variations and ecosystem implications of elevated atmospheric CO2. Plant Soil. 2003;254:291–303.

Flexas J, Bota J, Galmes J, Medrano H, Ribas-Carbo M. Keeping apositive carbon balanc eunder adverse conditions: responses of photosynthesis and respiration to water stress. Physiol Plant. 2006;127:343–52.

Gang C, Wang Z, Chen Y, Yue Y, Li J, Cheng J, Qi J, Odeh I. Drought-induced dynamics of carbon and water use efficiency of global grasslands from 2000 to 2011. Ecol Indic. 2016;67:788–97.

Hu Z, Yu G, Wang Q, Zhao F. Ecosystem level water use efficiency: a revi ew. Acta Ecol Sin. 2009;29:1498–507.

Hu ZM, Yu G, Fu Y, Sun X, Li Y, Shi P, Wang Y, Zheng Z. Effects of vegetation control on ecosystem water use efficiency within and among four grassland ecosystems in China. Glob Chang Biol. 2008;14:1609–19.

Huang G, Li Y, Mu X, Zhao H, Cao Y. Water-use efficiency in response to simulated increasing precipitation in a temperate desert ecosystem of Xinjiang, China. J Arid Land. 2017a;9:823–36.

Huang L, He B, Han L, Liu J, Wang H, Chen Z. A global examination of the response of ecosystem water-use efficiency to drought based on MODIS data. Sci Total Environ. 2017b;601-602:1097.

Huang M, PIao S, Sun Y, Ciais P, Cheng L, Mao J, Poulter B, Shi X, Zeng Z. Change in terrestrial ecosystem water-use efficiency over the last three decades. Glob Chang Biol. 2015;21:2366–78.

Huang M, Piao S, Zeng Z, Peng S, Ciais P, Cheng L, Mao J, Poulter B, Shi X, Yao Y. Seasonal responses of terrestrial ecosystem water-use efficiency to climate change. Glob Chang Biol. 2016;22:2165–77.

Jang K, Kang S, Lim YJ, Jeong S, Kim J, Kimball JS, Hong SY. Monitoring daily evapotranspiration in Northeast Asia using MODIS and a regional Land Data Assimilation System. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres. 2013;118:12927-12940.

Jang K, Kang S, Kim J, Hong SY. Retrievals of All-Weather Daily Air Temperature Using MODIS and AMSR-E Data. Remote Sensing. 2014;6(9):8387-8404.

Lin YS, Medlyn BE, Duursma RA, Prentice IC, Wang H, Baig S, Eamus D, Dios VRD, Mitchell P, Ellsworth DS. Optimal stomatal behaviour around the world. Nat Clim Chang. 2015;5:459–64.

Liu Y, Xiao J, Ju W, Zhou Y, Wang S, Wu X. Water use efficiency of China’s terrestrial ecosystems and responses to drought. Sci Rep. 2015;5:13799.

Luo Y, Zhao X, Huang Y, Su N, Feng J. Research progress on plant water use efficiency and its measuring methods. J Desert Res. 2009;29:648–55.

McCarthy HR, Pataki DE, Jenerette GD. Plant water-use efficiency as a metric of urban ecosystem services. Ecol Appl. 2011;21:3115–27.

Medlyn BE, De Kauwe MG, Lin YS, Knauer J, Duursma RA, Williams CA, Arneth A, Clement R, Isaac P, Limousin JM. How do leaf and ecosystem measures of water-use efficiency compare? New Phytol. 2017;216:758–70.

Mouat DA, Lancaster J. Desertification: impact. Encycl Soil Sci. Third Edition. CRC Press; 2017. p. 628–32.

Mu Q, Heinsch FA, Zhao M, Running SW. Development of a global evapotranspiration algorithm based on MODIS and global meteorology data. Remote Sens Environ. 2007;111:519–36.

Mu Q, Zhao M, Steven W. Improvements to a MODIS global terrestrial evapotranspiration algorithm. Remote Sens Environ. 2011;115:1781–800.

Niu S, Xing X, Zhang Z, Xia J, Zhou X, Song B, Li L, Wan S. Water-use efficiency in response to climate change: from leaf to ecosystem in a temperate steppe. Glob Chang Biol. 2011;17:1073–82.

Oki T, Kanae S. Global hydrological cycles and world water resources. Science. 2006;313:1068–72.

Picotte JJ, Rosenthal D, Rhode JM, Cruzan MB. Plastic responses to temporal variation in moisture availability: consequences for water use efficiency and plant performance. Oecologia. 2007;153:821–32.

Ponton S, Flanagan LB, Alstad KP, Johnson BG, Morgenstern K, Kljun N, Black TA, Barr AG. Comparison of ecosystem water-use efficiency among douglas-fir forest, aspen forest and grassland using eddy covariance and carbon isotope techniques. Glob Chang Biol. 2006;2(12):294–310

Potts DL, Huxman TE, Cable JM, English NB, Ignace DD, Eilts JA, Mason MJ, Weltzin JF, Williams DG. Antecedent moisture and seasonal precipitation influence the response of canopy-scale carbon and water exchange to rainfall pulses in a semi-arid grassland. New Phytol. 2010;170:849–60.

Reynolds JF, Maestre FT, Kemp PR, Stafford-Smith DM, Lambin E. Natural and human dimensions of land degradation in drylands: causes and consequences. In: Terrestrial ecosystems in a changing world. Berlin: Springer; 2007. p. 247–57.

Serrano-Ortiz P, Sánchez-Cañete EP, Oyonarte C. The carbon cycle in drylands. In: Lal R, Lorenz K, Hüttl RF, Schneider BU, von Braun J, editors. Recarbonization of the biosphere: ecosystems and the global carbon cycle. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands; 2012. p. 347–68.

Shurpali NJ, Biasi C, Jokinen H, Niina M, Pertti J. Linking water vapor and CO2 exchange from a perennial bioenergy crop on a drained organic soil in eastern Finland. Agric For Meteorol. 2013;168:47–58.

Simioni G, Le Roux X, Gignoux J, Walcroft AS. Leaf gas exchange characteristics and water- and nitrogen-use efficiencies of dominant grass and tree species in a West African savanna. Plant Ecol. 2004;173:233–46.

Sun Y, Piao S, Huang M, Ciais P, Zeng Z, Cheng L, Li X, Zhang X, Mao J, Peng S, Poulter B, Shi X, Wang X, Wang Y, Zeng H. Global patterns and climate drivers of water-use efficiency in terrestrial ecosystems deduced from satellite-based datasets and carbon cycle models. Glob Ecol Biogeogr. 2015;25:311–23.

Tallec T, Béziat P, Jarosz N. Crops’ water use efficiencies in temperate climate: comparison of stand, ecosystem and agronomical approaches. Agric For Meteorol. 2013;168:69–81.

Tang X, Ma M, Zhi D, Xu X, Li Y, Huang X, Gu Q, Song L. Remotely monitoring ecosystem water use efficiency of grassland and cropland in China’s arid and semi-arid regions with MODIS data. Remote Sens. 2017;9:616.

Vicente-Serrano SM, Beguería S, López-Moreno JI. A multiscalar drought index sensitive to global warming: the standardized precipitation evapotranspiration index. J Clim. 2010;23:1696–718.

Vicente-Serrano SM, Beguería S, Lorenzo-Lacruz J, Camarero JJ, López-Moreno JI, Azorin-Molina C, Revuelto J, Morán-Tejeda E, Sanchez-Lorenzo A. Performance of drought indices for ecological, agricultural, and hydrological applications. Earth Interact. 2012;16:1–27.

Xiao X, Hollinger D, Aber J, Goltz M, Davidson EA, Zhang Q, Iii BM. Satellite-based modeling of gross primary production in an evergreen needleleaf forest. Remote Sens Environ. 2004;89:519–34.

Xu H, Li Y. Water-use strategy of three Central Asian desert shrubs and their responses to rain pulse events. Plant Soil. 2006;285:5–17.

Xu H, Li Y, Xu G, Zou T. Ecophysiological response and morphological adjustment of two Central Asian desert shrubs towards variation in summer precipitation. Plant Cell Environ. 2007;30:399–409.

Yang Y, Guan H, Batelaan O, Mcvicar TR, Long D, Piao S, Liang W, Liu B, Jin Z, Simmons CTJSR. Contrasting responses of water use efficiency to drought across global terrestrial ecosystems. Science Report. 2016;6:23284.

Yang YH, Fang JY, Fay PA, Bell JE, Ji CJ. Rain use efficiency across a precipitation gradient on the Tibetan Plateau. Geophys Res Lett. 2010;37:78–82.

Yu G, Wang Q. Ecophysiology of plant photosynthesis, transpiration and water use. Beijing: Science Press; 2010.

Zhang LX, Zhou DC, Fan JW, Hu ZM. Comparison of four light use efficiency models for estimating terrestrial gross primary production. Ecol Model. 2015;300:30–9.

Zhang Y, Moran MS, Nearing MA, Campos GEP, Huete AR, Buda AR, Bosch DD, Gunter SA, Kitchen SG, Mcnab WH. Extreme precipitation patterns and reductions of terrestrial ecosystem production across biomes. J Geophys Res-Biogeo. 2013;118:148–57.

Zhu Q, Jiang H, Peng C, Liu J, Wei X, Fang X, Liu S, Zhou G, Yu S. Evaluating the effects of future climate change and elevated CO2 on the water use efficiency in terrestrial ecosystems of China (EI). Ecol Model. 2011;222:2414–29.

Zhu X. Researches on the dynamics, spatial variability and its underlying mechanisms of Water Use Efficiency in Chinese Terrestrial Ecosystems. Beijing: The University of Chinese Academy of Sciences; 2013.

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by a grant from the National Research Foundation of Korea (C1013479-01-01) and S. Kang was partly supported by a grant from Kangwon National University.

Funding

This work is supported by a grant from the National Research Foundation of Korea (C1013479-01-01) and S. Kang was partly supported by a grant from Kangwon National University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

WK undertook the literature review and case study analysis. WK and SK drafted the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Kang, W., Kang, S. On the use of alternative water use efficiency parameters in dryland ecosystems: a review. j ecology environ 43, 24 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41610-019-0122-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41610-019-0122-7